INTRODUCTION

Petronius’ fragmentary Satyricon is mostly renowned for the longest of its extant episodes, the so-called Cena Trimalchionis (26.9–78), which narrates a lavish dinner party hosted by the freedman Trimalchio.Footnote 1 The Cena takes the reader through an unprecedented show of extravagance that has long attracted scholarly attention.Footnote 2 Modern interest has focussed on a myriad of themes, studied from a host of diverse angles—from the literary investigation of the narrative techniques at work,Footnote 3 via the historical contextualization of the depicted socio-economic milieu,Footnote 4 to the linguistic analysis of the language of the dinner guests.Footnote 5 The presence of legal dimensions has been appreciated too, although the role of law in the Cena has been questioned outright.Footnote 6 The Cena's imperial innuendos have also received due comment. For instance, scholars interpreted the universe of the dinner party as a comic distortion of the imperial court and its culture,Footnote 7 along with spotting imperial habits and foibles in Trimalchio.Footnote 8 It is notable in this context that Trimalchio's feast also contains one of the highest concentrations of enslaved characters being punished in the whole of Roman literature. Although scholars have often understood these punishments in the context of the comedic aspects of the episode,Footnote 9 some have acknowledged the interpretative potential of these vignettes for revealing the harsher realities of Roman society in general and Roman slavery in particular.Footnote 10 Overall, however, these scenes are widely regarded as a distinctive element of Petronius’ characterization of the Cena's host—Trimalchio—as a boorish ex-slave, as recently outlined by Joshel:Footnote 11

at the dinner party of the wealthy freedman Trimalchio, the display of masterly violence serves as social criticism of this parvenu … these scenarios of punishment and reprieve portray the power of a vulgar freedman who has wealth but not class … his slaves then enable him to exercise a power denied by his social position, and Petronius’ depiction of its vulgar display makes the wealthy freedman ridiculous.

Seen this way, the theme of ‘crime and punishment’ serves to corroborate the Cena's satirical depiction of Roman freedpersons, typically agreed to be the chief purpose of the text.

This article offers a different interpretation of the Cena's satirical bite by taking a fresh look at the occurrence of ‘crime and punishment’ in scenes that involve enslaved characters. In particular, it provides a comprehensive overview of all the ‘crime and punishment’ scenes that have to do directly with Trimalchio. I foreground in the first instance the immediate purpose of the relevant sketches in the narrative—namely, to flesh out the imperial theme within the dinner party, with particular regard to the freedman's execution of domestic justice. Arbitrary and unfair, Trimalchio's jurisdiction is then exposed as a fierce satirical critique not so much of the main characters of the Cena—that is, the freedman host and his freed guests—as of the imperial government. The article thus argues that the established view of the freedman as the target of Petronius’ satirical pen is in need of revision.

I. THE SHAPE OF TRIMALCHIO'S DOMESTIC JURISDICTION

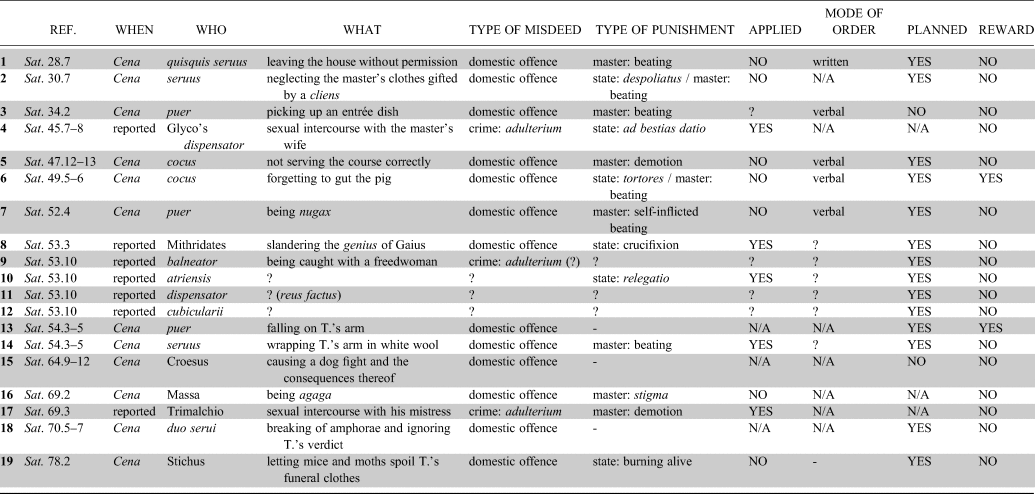

The Cena contains, in total, nineteen scenes of servile ‘crime and punishment’. Table 1 presents these in schematic fashion, following their order of appearance in the episode. A distinction between servile misdeeds and punishments happening during the dinner party vis-à-vis the reported instances (which become part of the banquet through secondary narration) is made at the outset. The table also foregrounds several other important structural aspects—namely, the type of servile misdeed committed or theorized (for example domestic offence/crime), the kind of punishment exerted or threatened (for example beating); and the power framework behind the punishment, that is, master/household or law/state (without wishing to imply a rigid barrier between these two frameworks). Dealing with punishments specifically, there is a further demarcation between, on the one hand, those ordered by Trimalchio to be meted out by his servile staff and, on the other hand, the chastisements which he is willing to exert himself. The table also distinguishes between accidental and planned scenes (that is, those carefully designed by Trimalchio). Finally, rewards are pointed out too, as they render explicit the non-casual nature of the situations to which they belong.

Table 1. Scenes of servile ‘crime and punishment’ in the Cena Trimalchionis

As noted in the Introduction, this article exclusively delves into the ‘crime and punishment’ scenes involving both enslaved characters and the host himself, showing how Petronius exploited these to craft, within the plot of the Cena, a subtle complementary narrative centred on Trimalchio's quasi-imperial authority. Despite their abundant number and variety, common threads can be found. These will be singled out first, before we confront the larger scheme that lurks behind those vignettes.

II. PLANNED AND UNPLANNED SCENES

The most commonly found element among the nineteen instances is Trimalchio's meticulous planning: nos. 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19. As these scenes demonstrate, the host's dominance over his household is such that he not only punishes his slaves excessively and wilfully (as will be seen) but also creates a stage for making them commit certain misdeeds in front of the guests’ eyes. Panayotakis has already argued that some of these orchestrated sketches buttress the theatrical dimension of the Cena, since they are deliberately staged by the host.Footnote 12 As the theatrical character of the banquet is mainly evident in the flamboyant presentation of the dinner courses, Panayotakis focusses on nos. 2, 6 and 18, where Trimalchio's creativity in parading the fine quality of his wine and dishes leverages on servile delinquency.Footnote 13 No. 6 constitutes, indeed, an excellent example of these scenes’ staged nature: Trimalchio orders a cook to be stripped (despolia!),Footnote 14 since he forgot to gut the pig that was supposed to be served, in itself a minor ‘crime’. The commensals intercede for the cook, but soon realize that they have been tricked: as the host asks the cocus to carve the pig's belly on the spot, sausages and black puddings are squeezed out of it. The rehearsed character of the scene is also confirmed by the rewarding of the cook's performance with a silver crown and a drink (50.1), in place of punishment.Footnote 15

Apart from demonstrating Trimalchio's control, these scenes also advance further characterizations of the dinner host:Footnote 16

i) he brandishes his material possessions, as demonstrated in no. 7—where Trimalchio's reaction to the puer's tossing (proiecit) of a wine glass amplifies the boast about his refined collection of vases and cups—but also in nos. 3, 15 and 18;

ii) his power is undisputed, as illustrated chiefly by nos. 8, 13, 14 and 19;

iii) he benefits from a highly specialized servile staff, as shown by nos. 5, 6 and 12, which respectively bring into play uiatores, tortores and cubicularii;

iv) he displays to the guests a merciful attitude towards his servile staff, such as in nos. 3, 5, 6, 7, 13, 15, 18 and 19. As an example of this mercy, we can mention no. 5, where the punishment of demotion to another office is not actually meted out to the cook; it is just a threat to make him serve the course scrupulously.

There are only two scenes that portray what may be called seemingly unexpected accidents: nos. 3 and 15. As with the staged scenes just discussed, these unforeseen mishaps also function to advance several of the Cena's characterizations: impeccable at improvising, the host turns also these instances into occasions to show utter indifference towards his material possessions.Footnote 17 First, in no. 3, the accidental (forte) dropping of an entrée dish makes Trimalchio rebuke a puer, not for the material loss but rather because he picked up the plate, lowering the tone of the household with such an act.Footnote 18 Since Petronius does not add details on the fate of the puer, but rather concentrates on the swift appearance of another attendant sweeping the refuse away, there are doubts as to whether this punitive order has been applied or not. On the same note, in no. 15, Croesus, Trimalchio's jealous favourite, unexpectedly provokes his puppy to attack the dog Scylax, whom the host has just passionately praised. The canine mayhem results in the shattering of crystal vases and a precious lamp (which sprinkles burning oil on the guests) under the impassive gaze of Trimalchio who is described as unwilling to seem upset at his loss (ne uideretur iactura motus).

III. WEALTH AND POWER

So far it seems that the ‘crime and punishment’ scenes have been set up or exploited by Trimalchio mainly to show off his wealth, confirming the display of the vulgarity of this nouveau riche which pervades the whole banquet. However, most of the planned and unplanned instances also reveal an interest in parading an authority untypical of a private master, even an immensely rich one:

i) Trimalchio has a habit of ordering chastisements, either in a written form (no. 1), or verbally (nos. 3, 5, 6, 7); in the latter case, he delegates the punitive tasks, reaching an ironic peak of this delegation pattern in no. 7, where he orders a puer to punch himself;

ii) the freedman follows a wilful identification of misdeeds and punishments (nos. 13, 14 and 15), exemplified by a seruus receiving a reward instead of a chastisement when he injures Trimalchio's arm in no. 13;

iii) the arbitrariness that characterizes the scenes (item ii) is accompanied by clear abuses of Trimalchio's masterly powers in nos. 8 and 19, in which the state punishments of crucifixion and burning alive appear;

iv) the host's authority, however, not only is based on violence but also benefits from allusions to judicial figures (no. 18, the praetor) and infrastructures which seem borrowed from the state (nos. 11 and 12).

IV. SAMPLING THE IVS CENAE, CONSTRUCTING IMPERIAL AUTHORITY

This overview of servile ‘crime and punishment’ has underscored the pervasiveness of this theme and the presence of a sui generis justice system in Trimalchio's house. The present section will clarify the imperial matrix of this domestic jurisdiction.

Some of the Cena's punishment sketches have been connected in the past with the construction of an imperial thread, albeit not systematically. Walsh has already briefly signalled that Trimalchio uses ‘the trappings and the justice of the imperial court’;Footnote 19 a closer, methodical look at the identified planned instances, however, will go further to clarify that the imperial power sees a tangible material representation not only in the fasces, secures and tabulae adorning Trimalchio's houseFootnote 20 but also in the actual execution of justice in his household.

Let us begin with the first instance (no. 1), constituted by the signpost that Encolpius reads as he is about to cross the threshold (28.7):Footnote 21

quisquis seruus sine dominico iussu foras exierit accipiet plagas centum.

Any slave going out without the master's order will receive one hundred blows.

This inscription has a mock imperial tone,Footnote 22 and constitutes a first hint at the kind of authority Trimalchio wishes guests and readers to attribute to himself: his unchallenged control over the household needs to be clarified before entering his ‘realm’. In line with this premise, throughout the dinner the freedman host uses only the threat of chastisements to make his domestic staff abide by his absurd rules.

In no. 18, towards the end of the banquet, Trimalchio does not resort to beating when he intervenes in a drunken fight between two of his slaves (70.4–6):

cum ergo Trimalchio ius inter litigantes diceret, neuter sententiam tulit decernentis, sed alterius amphoram fuste percussit. consternati nos insolentia ebriorum intentauimus oculos in proeliantes notauimusque ostrea pectinesque e gastris labentia, quae collecta puer lance circumtulit.

Trimalchio administered justice to the disputants, but neither of them accepted his verdict, and they smashed each other's waterpots with sticks. Perplexed by their drunken insolence, we stared at them fighting, and noticed that their pots were dropping oysters and scallops, which a boy picked up and served around on a tray.

Predictably, as this is an expedient to serve shellfish in an unconventional way, the actual punitive action is missing. On the other hand, the striking feature of the scene lies in the portrayal of the host as a praetor, since the formula ius dicere is unequivocally related to this state magistrate. This conveys the impression that some sort of official jurisdiction is being exercised in this private domus.

This theme is taken further in Sat. 53, where a clerk of Trimalchio suddenly invades the dining room, declaiming a report on his Cumaean estate which reminds Encolpius of the Vrbis acta.Footnote 23 The parallel between this sort of daily gazette (which, during the Imperial era, mostly concerned matters directly related to the imperial house)Footnote 24 and the Cumaean bulletin constitutes an explicit clue to the imperial nature of the scene. What is more, this report includes the mention of a dispensator who has been formally convicted (reus factus, no. 11) and some cubicularii who have taken each other to court (no. 12). The fundus thus figures almost as a province of the domus. In both domains, judicial infrastructures similar to those of the state are in place—although they do not seem to be working properly. Being unable to prevent the numerous miscarriages of justice taking place both in the house and in the estate, they represent, as will be seen, more a façade than an actual form of legal assistance.Footnote 25

The cubicularii mentioned above could have been simple servile bedroom servants but also people in charge of admitting access to a persona publica, as happened with officials already in the Early Republic.Footnote 26 Emperors started considering them as personal servants and confidants.Footnote 27 They are not the only category of interest among the serui who appear in the punishment sketches. With the threat of demoting the cook to the decuria of uiatores (no. 5),Footnote 28 Trimalchio alludes to magistrate assistants to whom he was technically not entitled as a seuir Augustalis.Footnote 29 These messengers, who were salaried by the state and had to be free during their appointment, served emperors, praetors, tribunes and consuls, along with some of the uigintiuiri.Footnote 30

A few specifications need to be added regarding the servile staff performing punitive tasks. They appear to be characterized as state functionaries who help Trimalchio in consolidating his domestic justice system. In particular, no. 6 contains the verb despoliare, which also has the technical meaning of undressing for punitive purposes.Footnote 31 The verb alludes to the figure of the lictores, whom Trimalchio, as a seuir Augustalis, was entitled to have.Footnote 32 However, lictores are exclusively portrayed in the act of despoliare (along with spoliare) when stripping the coerced criminal naked before the actual chastisement.Footnote 33 Not all lictores performed this punitive action, but only those of magistrates with imperium (which gave them also capital coercitio, that is, the power of scourging and meting out capital punishment).Footnote 34 Trimalchio's lictors must therefore be linked to the aforementioned fasces and secures and not to his role as seuir. No. 6 also features tortores, who are normally owned by the state.Footnote 35 Curiously, tortores are also an asset of which the tyrant, or the king portrayed with tyrannical features, frequently takes advantage.Footnote 36

If exerting punishment seems to be a prerogative of the servile staff, an exception to the noted trend to delegate is represented by no. 19. During his mock funeral, Trimalchio advises the enslaved Stichus to meticulously guard his grave clothes, including a toga praetexta, with the following brutal threat (78.2):

uide … ne ista mures tangant aut tineae, alioquin te uiuum comburam.

make sure neither mice nor moths touch them, otherwise I'll burn you alive.

This is the only case in which Trimalchio implies through a threat that he is ready to impart such a cruel (and at first sight unjustified) punishment himself. The host's disproportionate reaction not only arises from a factually incomprehensible reason but also overreaches the options for punitive action afforded to a private individual in his capacity as dominus. Indeed, burning alive is a form of state punishment, as it can be inferred by the exclusively public offences that incur such treatment in the relevant juridical discussion assembled in the Digesta.Footnote 37 The Pauli Sententiae also records this as the penalty prescribed for people of low rank (humiliores) who committed crimen maiestatis, further enhancing this point;Footnote 38 yet uiuicomburium is (potentially) used here by a private dominus, and for a trivial damage.

A similar application of a state punishment in the private domain features in no. 8, which again belongs to the Vrbis acta section. Among the memorable events recalled at the beginning of this oral gazette, a crucified seruus, who slandered the genius of his master,Footnote 39 stands out (53.3):

Mithridates seruus in crucem actus est, quia Gai nostri genio male dixerat.

The slave Mithridates was crucified, since he had cursed the genius of our Gaius.

Crucifixion, if applied formally, is another punishment overseen and executed by the state.Footnote 40 This is confirmed not only by Petronius’ patent association between the cross and state magistrates (si magistratus hoc scierint, ibis in crucem, ‘if the magistrates find out, you will go to the cross’, 137.3) but also by the type of offences punished as such in the legal sources, all of which have impacts beyond the small world of the household.Footnote 41 None the less, once again Trimalchio is presented using a state punitive tool against one of his serui, this time not in his domus but on his fundus.

Focussing on the clerk's words, moreover, one realizes that, in referring to his genius, Petronius prefers the genitive of Gaius (that is, Gai) to that of Trimalchio's cognomen.Footnote 42 The stress on Trimalchio's praenomen is not simply aimed at showing that the dinner host boasts the tria nomina;Footnote 43 rather, it also constitutes a conspicuous play on the crimen maiestatis (normally translated as ‘treason’)Footnote 44 and on certain emperors (normally addressed as Gaii) who were fond of this accusation.Footnote 45 Treason is understood by Ulpian as a crime committed against the Roman people or against their safety (Dig. 48.4.1).Footnote 46 Its definition, however, is complex. Bauman astutely identified a dichotomy between the ‘Republican categories’ of this crime, namely those regarding the security of the state,Footnote 47 and the injuries (whether verbal or real) pertaining to the emperor and his deified predecessors.Footnote 48 With the emperor impersonating the whole body of citizens and its maiestas (being endowed with the imperium and tribunician sacrosanctity, as well as appearing as the head of the state's religious order), the boundaries between the two categories became blurred and the accusation for this crime was open to abuse. Suetonius, for instance, testifies that during Tiberius’ reign it was considered to be an offence to the imperial maiestas also to beat a slave or to change one's clothes near a statue of Augustus, as well as to carry a ring or a coin with the image of the emperor to a privy or to a brothel and to criticize any act or word of his predecessor (Tib. 58). Moreover, this crime ‘is not committed only through acts, but it is very much exacerbated by impious words and curses’.Footnote 49

In light of this, the hypothesis of Mithridates’ cursing as an act endangering the imperial maiestas is plausible. Whether the offended maiestas is that of the emperor or Trimalchio's, who would thus receive an implicit imperial characterization, is intentionally left ambiguous. In any case the punishment must have been exemplary. Literary sources display considerable flexibility concerning maiestas not only in terms of admitting charges but also regarding the imposition of penalties. Those prescribed by the law (interdiction from water and fire, originally) were rapidly exceeded by the court of the princeps and the consular court, under whose jurisdiction the crime against maiestas came. The Senate started intensifying punishments in cases involving the princeps himself, in an attempt to please him. Both courts eventually caused the disappearance of interdictio, with banishment and harsher forms of execution, especially for people of lower social standing, being commonly imposed.Footnote 50 Hence, given that Mithridates is labelled a seruus, it makes sense to find him crucified, having committed an act equated to a breach of maiestas. That said, Trimalchio seems here to overreach his masterly capacities, much like emperors tended to go beyond the law in judging cases of lèse-majesté directly pertaining to them.

Evidently we are witnessing a world out of balance, in which the larger-than-life dinner host displays his wilfulness and power towards his serui. But Trimalchio's jurisdiction is also oddly similar to the imperial one. On a deeper scrutiny, it appears to carry and even inflate all the flaws of the latter, as exemplified by the absurd crimen maiestatis case just discussed. Moreover, the pattern of threatening but not enacting chastisements constitutes an indisputable play on the imperial virtue of clementia, the tendency to cultivate mercy and reject cruelty that someone who is in a position of power must show.Footnote 51

The ‘crime and punishment’ scenes therefore cohere to create Trimalchio's justice system, one characterized by absolute control from above. The appearance of a state magistrate such as the praetor and that of state functionaries in the domus, along with the presence of a proper court in the fundus, frames the sketches in a pseudo-public setting. These features work together with the more subtle legal resonances that were traced with due reference to the legal sources to make the imperial connotations of Trimalchio's abuses of power abundantly clear.

V. PURPLE WOOL: A REVEALING INSTANCE

As seen in the preceding section, the ‘crime and punishment’ scenes that involve Trimalchio deepen the broader imperial theme that scholars have long recognized in the Cena. However, only when we focus our attention on a scene that seemingly follows a different design does the meaning of ‘crime and punishment’ in the manner of Trimalchio become fully apparent. Trimalchio fails to follow his modus operandi of vividly envisaging punishments for serui who are then forgiven in just one case during the dinner party, namely the scene containing nos. 13 and 14; but this rarity serves to throw into relief the importance of these actions.

Thus in the midst of an acrobat show a puer slips, falling (we assume)Footnote 52 on Trimalchio's arm (54.1). The host moans loudly, alerting a squad of first-aiders, Fortunata and part of the servile staff in the vicinity. This is a scene designed by Trimalchio, despite the chaotic atmosphere that has convinced many commentators to the contrary; a key argument used to explain this as an accident happening outwith Trimalchio's control is the impossibility of planning a ‘safe’ fall of the puer without entailing a serious injury for the host.Footnote 53 None the less, the culinary prodigy of the pig that was not gutted (no. 6) would also have been arduous to accomplish, yet nothing is impossible in Trimalchio's domus. Moreover, Encolpius, offering us a clue as to how the narrator expects us to interpret the scene (that is, as a planned occasion) plainly juxtaposes the present instance with the trick of the pig (54.3–5):

nam puer quidem, qui ceciderat, circumibat iam dudum pedes nostros et missionem rogabat. pessime mihi erat, ne his precibus per ridiculum aliquid catastropha quaeretur. nec enim adhuc exciderat cocus ille, qui oblitus fuerat porcum exinterare. itaque totum circumspicere triclinium coepi, ne per parietem automatum aliquod exiret, utique postquam seruus uerberari coepit, qui bracchium domini contusum alba potius quam conchyliata inuoluerat lana. nec longe aberrauit suspicio mea; in uicem enim poenae uenit decretum Trimalchionis, quo puerum iussit liberum esse, ne quis posset dicere tantum uirum esse a seruo uulneratum.

The fallen puer was crawling around our feet, begging for mercy. I had the weird feeling that among his whining some funny coup de théâtre was planned. That cook who forgot to gut the pig had not slipped my mind. So I started looking around the dining room, in case some contraption should emerge from the wall, especially after the slave who wrapped the injured arm of the master in white wool, instead of purple wool, started being beaten. My suspicion did not wonder far: indeed, instead of a punishment a decree of Trimalchio came, in which he ordered to free the puer, so that no one could say that such a great man was hurt by a slave.

Encolpius’ association between this scene and no. 6 is underscored by how these passages contain the sole instances of enslaved characters being rewarded. Just as the cook's acting deserves a drink and a silver crown (50.1), the acrobat puer is manumitted (no. 13). Obviously, the task of falling on Trimalchio's arm without hurting him was a more demanding one, carrying a higher risk for the acrobat himself too. This manumission is, at any rate, a bewildering provision.Footnote 54

At the same time, oddly, the slave providing medical assistance is punished (no. 14). It is not the first time that Trimalchio shows a bewildering attitude in meting out punishments. Let us compare the present instance with no. 15 that has already been mentioned (64.11–12):

Trimalchio ne uideretur iactura motus, basiauit puerum ac iussit super dorsum ascendere suum. non moratus ille usus est equo manuque plena scapulas eius subinde uerberauit, interque risum proclamauit: ‘bucca, bucca, quot sunt hic?’

Trimalchio, unwilling to seem upset at this loss [sc. the precious vases shattered by the dogs while fighting], kissed the boy and made him climb on his back. Croesus instantly mounted his horse and hit Trimalchio's shoulders with his open hand, yelling amid laughter: ‘Mouth, mouth, how many are there?’Footnote 55

Not only does Croesus get off scot-free, but, pretending to play, he is also allowed to teach Trimalchio a lesson: he imparts his master the beating which he himself should have suffered. If one could have made sense of Trimalchio's peculiar attitude here through the fact that Croesus is his deliciae,Footnote 56 and therefore benefits from unusual treatment, nos. 13 and 14, involving a ‘simple’ puer and a seruus respectively, rather confirm this idea of a wilful system, where the identification of servile misdeeds is really unpredictable.

The seruus in no. 14 is also the only slave to be undoubtedly punished during the banquet. In contrast to the puer picking up an entrée dish (no. 3), whose punishment was not recorded by Petronius, here the seruus is already suffering the beating when Encolpius directs his gaze towards him. Choosing white instead of purple for Trimalchio's bandage, a seemingly quite negligible ‘domestic’ offence, results in a show of violence in plain sight: this is a manifest exception to Trimalchio's habit of threatening and shunning punishments during the dinner party. As Trimalchio designed this scene, discussed above, we should take a closer look at the meaning of the purple cloth he requested to understand the freedman's reaction—since he himself stated earlier nihil sine ratione facio (‘I do nothing without a reason’, 39.14). Doing so will demonstrate that no. 14 contains a much sharper play on the justice system within the imperial theme than hitherto realized, especially if seen against the backdrop of the other ‘crime and punishment’ scenes.

Traditionally, Trimalchio's reaction to his arm being wrapped in white wool is explained with reference to his superstition, confirming an attitude amply shown by the host throughout the Cena.Footnote 57 Indeed, Romans believed that purple-red had healing properties; amulets wrapped up in purple materials were employed against fever and headache, as explained by Casartelli.Footnote 58 In linking these amulets to no. 14, however, she also mentions Sat. 131, which takes place outside of the episode of the Cena. There, following an old woman's advice, Encolpius tosses enchanted pebbles, which had been enveloped in purple-red fabric, in his underwear to treat his impotence. In Sat. 131 this is actually the case: the healing power relies on the colour of the cloth. However, the correlation between the use of these remedies with Trimalchio's conchyliata lana in no. 14 does not appear as strong. On one level, Casartelli's interpretation certainly works, as Trimalchio is both injured and superstitious; yet there is a possible further meaning pertaining to the desired colour.

In a hierarchical society such as the Roman one, clothing colours served to establish an immediate link with the social rank of the people wearing them.Footnote 59 Specifically, conchyliatus is related to purple-red, a luxurious and prestigious colour which comes in different shades. Pliny notes (HN 22.3):

iam uero infici uestes scimus admirabili fuco, atque, ut sileamus Galatiae, Africae, Lusitaniae e graniis coccum imperatoriis dicatum paludamentis, transalpina Gallia herbis Tyria atque conchylia tinguit et omnes alios colores.

we know that garments are dyed with an extraordinary vegetal dye, and, to say nothing of the fact that, among the berries of Galatia, Africa and Lusitania, coccum is reserved for the military cloaks of generals,Footnote 60 and that Transalpine Gaul produces with herbal dyes Tyrian purple,Footnote 61 oyster purple (conchylia)Footnote 62 and all the other colours.

These three gradations of purple-red all appear in the Cena and exclusively in relation to Trimalchio. At the beginning of the narrative, the protagonists spot him casually playing with green balls with some of his enslaved household members. Being depicted as probably unaware of being watched, his outfit simply consists of a tunica russea and his slippers (27.1). By contrast, after his thermal bath, he is swathed in a coccina gausapa (28.4), getting ready for his dazzling entrance in a dining room full of guests. On this occasion, he also wears a pallium coccineum and a laticlauia mappa, a napkin with the senatorial stripe (32.2). At 38.5, the list of Trimalchio's possessions, comprising agricultural products and livestock, is weirdly capped off with the mention of the numerous pillows in the dining room that are all purple-red (conchyliatum aut coccineum). Finally, in no. 2, Trimalchio's dispensator brags about his stolen clothes being made with Tyrian dye, although their cheap value of ten sesterces leads the reader to think that this was a simple pretentious claim.Footnote 63

If green and red are the dominant colours of Trimalchio's household,Footnote 64 the more coveted shades of red remain Trimalchio's personal prerogative:Footnote 65 he wears them when certain to be under his guests’ gaze; moreover, he uses them to embellish his ‘ceremonial hall’ (that is, the dining room). Similarly, the lana conchyliata of no. 14 is part of a show carefully rehearsed by the freedman. Purple is not only an extreme luxury but also an appanage of senators and magistrates; and the efforts made by Caligula, Nero and Domitian to limit its use to imperial symbols and official purposes stress that this colour was deeply connected to the supreme power of the emperor.Footnote 66 The colour by itself thus underscores Trimalchio's imperial set-up. More critically, seen against this backdrop, the scene reveals an important nuance; when Trimalchio is denied the lana conchyliata, a prerogative of his claim to absolute authority (that is, to imperial status) is, by extension, not recognized by the slave. It is for this reason that the seruus deserves punishment: through the use of purple wool, Trimalchio demands open and unmistakable recognition of his superior imperial authority.

As discussed above, this scene is orchestrated by Trimalchio. The forcing in no. 13 of the guests to watch the beating recalls the role of public punishment in ancient Rome. Let us consider Cicero's claims about punishment in his De officiis and De legibus: fear of punishment (poenae metus) has the greatest efficacy in preventing crimes, while the purpose of punishment is to promote the benefit of the community. The Ciceronian notion of utilitas publica will remain a linchpin of the theory of punishment, as confirmed three centuries later by Callistratus, according to whom the execution of brigands on the gallows had to be public for two reasons: the sight would have deterred the community from committing similarly deplorable acts and would have given the offended part some consolation.Footnote 67 Considered with this in mind, the open nature of the punishment in no. 13 underscores further the public nature of Trimalchio's justice system: the beating of the seruus is promptly meted out in front of the guests’ eyes to work as a warning for them. In sum, the fact that the scene is the only one in which a punishment is actually applied is indicative of the importance of the underlying claim: Trimalchio's authority, being of an imperial nature, must not be overlooked, offended or challenged, not even by analogous (and seemingly innocent) behaviours.

Trimalchio's imperial characterization, foregrounded at the outset of the Cena with the inscription in no. 1, is strengthened by the wool-wrapping incident (no. 14) in the middle of the episode and reaches its peak at its end, with no. 19. The reading of no. 14 offered here also sheds new light on no. 19. The uiuicrematio promised to Stichus, in case he does not guard Trimalchio's grave gear, can be seen as another case of lèse-majesté: the potential spoiling of the toga praetexta, which has a purple border,Footnote 68 emerges again as a direct insult to the imperial persona of Trimalchio. The link with maiestas is corroborated by the fact that burning alive was also one of the punishments prescribed for this crime, when committed by humiliores, as discussed earlier.Footnote 69 Hence the damage of such a symbolic garment puts the potential offence on the same level as maiestatis deminutio cases, in which, as already seen, emperors were allowed to disregard the law, just like Trimalchio does here, overcoming, in his case, the possibilities afforded to a private master.

But Trimalchio's reactions in nos. 14 and 19 also strengthen the link between his punitive behaviour and his fake clementia. According to Seneca, nothing is more glorious (gloriosius) than an emperor who, when wronged, decides to remain unavenged (Clem. 1.20.3). Trimalchio's serui are forgiven for the trivial offences of which they are accused, including when they are a nuisance to the guests (nos. 15 and 18); however, punishment is inescapable when they directly insult the host through the cursing of his genius (no. 8), the denial of the imperial purple (no. 14), and the potential spoiling of his purple funeral attire (no. 19). All told, neither clementia nor justice is in place: Trimalchio's justice system figures as unpredictable, unfair and tailored entirely to Trimalchio's need for status recognition. The Ciceronian stress on the benefit of the community has vanished too.

CONCLUSION

The many scenes pertaining to servile ‘crime and punishment’ in the Cena have long been recognized as increasing the reader's amusement; it is undisputed that they create immediately humorous detours. Yet, far from considering Trimalchio's serui as background figures fit only to be lampooned, Petronius conceptualized them as pivotal elements of the spectacle that he staged during his banquet. The sketches of ‘crime and punishment’ cohere to create an image of a justice system that adds a vital dimension to the wider imperial theme noted in other aspects of the Cena.

While previous commentators tried to uncover specific emperors behind Trimalchio's fixations,Footnote 70 the ‘crime and punishment’ theme goes beyond the ridicule and critique of a single reign, constituting instead a powerful satirical take on Roman imperial justice. Trimalchio's dining room-turned-court closely resembles the public one, especially in its shortcomings: what constitutes a misdeed is at Trimalchio's discretion, much as determining punishments is exclusively his prerogative and there is no appeal against his decisions. Trimalchio has also assimilated and substituted the traditional figures of justice, as he presents himself as a praetor and disposes of legal infrastructures on his fundus. The freedman's household is a satirical microcosm of the state at large, providing a parody of the enormously powerful and central role of the emperor in relation to the law. Through the prism of satire Petronius manifests the preludes of a dangerous tendency that will culminate in the third century with the consecration of the emperor as the supreme source of justice: it is not merely the lack of justice that concerns the author but also its channelling through a sole authority. To return to where we began, although the Cena works at a superficial level as an attack on the supposed pretentiousness and lack of taste of liberti, a sustained analysis of slave ‘crime and punishment’ episodes shows, by contrast, that it is the emperor, not the freedman, who is the ultimate object of derision—thus questioning the generally agreed direction of Petronius’ satirical pen.