Article contents

Redistribution of Land and Houses in Syracuse in 356 b.c, and its Ideological Aspects

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The story of Dion of Syracuse was told by ancient writers, and is still being told by modern historians, in the main as a story of ‘freedom versus tyranny’. The liberation of the greatest state in the Hellenic world from the rule of the most powerful tyrants' house in Greek experience fired the imagination and aroused the admiration of contemporary and later writers. There is, however, another side to the story of Dion.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1968

References

page 208 note 1 Nepos, , Dion 5. 1Google Scholar. In the account of Dion's preparations in Plutarch, , Dion 22Google Scholar, Herakleides is not mentioned. However, , I.G. iv. 1504Google Scholar, an inscription from Epidauros in which Dion and Herakleides are referred to as holding together the honorary office of ![]() (11. 39–40), upholds Nepos. This is a welcome reminder how careful we should be about the predominantly pro-Dionean tradition preserved in the extant sources. The main sources of Plutarch’s Dion—our fullest account of the career of Dion—have been recognized as Timonides and Timaios. Timonides of Leukas was a member of the Academy, who took part in Dion's expedition and commanded troops under him. In the form of a letter to Speusippos he gave an account of Dion's Sicilian expedition. He had, to be sure, firsthand knowledge of the facts but with it went an unbounded admiration for Dion and enthusiasm for his enterprise. Strongly laudatory of Dion and critical of Herakleides was also the account of Timaios of Tauromenium. Timaios may well have used Timonides to supplement his own information, but it is practically impossible to distinguish between the two in the accounts preserved. To both of them Herakleides is ‘the villain of the piece’ and therefore they dissociate him from ‘Dion the hero’ altogether. Ephoros (in Diodoros) and Theopompos were also, in general, laudatory of Dion, but less enthusiastic about Dion and less antagonistic to Herakleides and the popular cause than Timonides and Timaios. The Platonic letters referring to Dion's career (Epp, iii, iv, vii, viiiGoogle Scholar), though Plato was very close to Dion, do not display any noticeable animosity toward Herakleides. The only pro-Herakleidean and anti-Dionean contemporary account which left some traces in the extant sources was that of Athanis of Syracuse. Athanis wrote a History of Sicily in thirteen books. He was associated with Herakleides and was one of the twentyfive strategoi elected after Dion's deposition. The latter part of Nepos' Vita Dionis, which is unfavourable to ‘the liberator’, may be ultimately deriving from Athanis, as may be the rare notices unfavourable to Dion and favourable to Herakleides in Diodoros. See on the sources, e.g., Beloch, , G.G. iii. 2. 47 f.Google Scholar; Ed. Meyer, G.d.A. v. 512 f.Google Scholar; Lenschau, , R.E., s.v. Herakleides (24), col. 461Google Scholar; Westlake, , ‘Dion: A Study in Liberation’, Durham Univ. Journ., xxxviii (1946), 38 f.Google Scholar; Berve, , Dion; Abh. d. Akademie d. Wissensch. u. d. Literatur (Wiesbaden, 1957), 7–17Google Scholar; Jacoby, , Fr. Gr. Hist. no. 561 (Timonides), no. 562 (Athanis)Google Scholar; cf. also Harward, , The Platonic EpistlesGoogle Scholar; Morrow, , Studies in Platonic EpistlesGoogle Scholar; and especially Biedenweg, , Plularchs Quellen in den Lebensbeschreibungen des Dion und Timoleon (Leipzig, 1884)Google Scholar, and, recently, Brown, , Timaeus of Tauromenium (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1958), 19–20 and passim.Google Scholar

(11. 39–40), upholds Nepos. This is a welcome reminder how careful we should be about the predominantly pro-Dionean tradition preserved in the extant sources. The main sources of Plutarch’s Dion—our fullest account of the career of Dion—have been recognized as Timonides and Timaios. Timonides of Leukas was a member of the Academy, who took part in Dion's expedition and commanded troops under him. In the form of a letter to Speusippos he gave an account of Dion's Sicilian expedition. He had, to be sure, firsthand knowledge of the facts but with it went an unbounded admiration for Dion and enthusiasm for his enterprise. Strongly laudatory of Dion and critical of Herakleides was also the account of Timaios of Tauromenium. Timaios may well have used Timonides to supplement his own information, but it is practically impossible to distinguish between the two in the accounts preserved. To both of them Herakleides is ‘the villain of the piece’ and therefore they dissociate him from ‘Dion the hero’ altogether. Ephoros (in Diodoros) and Theopompos were also, in general, laudatory of Dion, but less enthusiastic about Dion and less antagonistic to Herakleides and the popular cause than Timonides and Timaios. The Platonic letters referring to Dion's career (Epp, iii, iv, vii, viiiGoogle Scholar), though Plato was very close to Dion, do not display any noticeable animosity toward Herakleides. The only pro-Herakleidean and anti-Dionean contemporary account which left some traces in the extant sources was that of Athanis of Syracuse. Athanis wrote a History of Sicily in thirteen books. He was associated with Herakleides and was one of the twentyfive strategoi elected after Dion's deposition. The latter part of Nepos' Vita Dionis, which is unfavourable to ‘the liberator’, may be ultimately deriving from Athanis, as may be the rare notices unfavourable to Dion and favourable to Herakleides in Diodoros. See on the sources, e.g., Beloch, , G.G. iii. 2. 47 f.Google Scholar; Ed. Meyer, G.d.A. v. 512 f.Google Scholar; Lenschau, , R.E., s.v. Herakleides (24), col. 461Google Scholar; Westlake, , ‘Dion: A Study in Liberation’, Durham Univ. Journ., xxxviii (1946), 38 f.Google Scholar; Berve, , Dion; Abh. d. Akademie d. Wissensch. u. d. Literatur (Wiesbaden, 1957), 7–17Google Scholar; Jacoby, , Fr. Gr. Hist. no. 561 (Timonides), no. 562 (Athanis)Google Scholar; cf. also Harward, , The Platonic EpistlesGoogle Scholar; Morrow, , Studies in Platonic EpistlesGoogle Scholar; and especially Biedenweg, , Plularchs Quellen in den Lebensbeschreibungen des Dion und Timoleon (Leipzig, 1884)Google Scholar, and, recently, Brown, , Timaeus of Tauromenium (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1958), 19–20 and passim.Google Scholar

page 208 note 2 There was no breach between Dion and Herakleides at this stage. According to Diod, . 16. 16. 2Google Scholar (based on Ephoros), Herakleides had been left by Dion in the Peloponnese in charge of the fleet, and was prevented by a storm from joining Dion in time, as planned. In Dion 32. 4 (based either on Timonides or on Timaios), Herakleides is said to have quarrelled with Dion in the Peloponnese and to have gone to Sicily on his own ![]() The version of Ephoros should be preferred on this point to the patently partisan version in Plutarch's Dion. Beloch, , G.G. iii. 1. 257 n. 3Google Scholar shows, by analysing the forces taken by Dion and those led by Herakleides, that there must have been a planned division, not a breach. A plausible explanation of this division of forces on military grounds is given by Thiel, , Rond het Syracusaansse experiment (Mededeelingen d. Nederland. Ak. van Weltenschappen, N. R. Deel 4, no. 5 (1941), 164 ff.)Google Scholar. Westlake, Recently, Durham Univ. Journ. xxxviii (1946), 38 f.Google Scholar, took up again the erroneous view that a breach between Dion and Herakleides occurred at this stage. There is nothing to commend Westlake's argument, and his conjectures as to the possible causes of a quarrel are not at all convincing. For the circumstances of the breach between Dion and Herakleides, which occurred some time after the latter's arrival in Syracuse, , see below, p. 210.Google Scholar

The version of Ephoros should be preferred on this point to the patently partisan version in Plutarch's Dion. Beloch, , G.G. iii. 1. 257 n. 3Google Scholar shows, by analysing the forces taken by Dion and those led by Herakleides, that there must have been a planned division, not a breach. A plausible explanation of this division of forces on military grounds is given by Thiel, , Rond het Syracusaansse experiment (Mededeelingen d. Nederland. Ak. van Weltenschappen, N. R. Deel 4, no. 5 (1941), 164 ff.)Google Scholar. Westlake, Recently, Durham Univ. Journ. xxxviii (1946), 38 f.Google Scholar, took up again the erroneous view that a breach between Dion and Herakleides occurred at this stage. There is nothing to commend Westlake's argument, and his conjectures as to the possible causes of a quarrel are not at all convincing. For the circumstances of the breach between Dion and Herakleides, which occurred some time after the latter's arrival in Syracuse, , see below, p. 210.Google Scholar

page 209 note 1 Taking Dion's expeditionary force as about 1,500 (cf. Beloch, , G.G. iii. 1. 257 n. 3)Google Scholar, and the overall number of volunteers armed by Dion in Sicily as 5,000 (cf. Plut, . Dion 27).Google Scholar

page 209 note 2 The date is September 357 B.C. The strategoi were chosen: ![]()

![]()

![]() (Diod, . 16. 10. 3Google Scholar). Ten of them were chosen out of the returned exiles.

(Diod, . 16. 10. 3Google Scholar). Ten of them were chosen out of the returned exiles. ![]() would seem to stand here for

would seem to stand here for ![]() in Plut, . Dion 28. 4Google Scholar, also

in Plut, . Dion 28. 4Google Scholar, also ![]()

![]() ibid. 37. 7 (Megakles subsequently disappears from the story).

ibid. 37. 7 (Megakles subsequently disappears from the story).

page 209 note 3 Plut, . Dion 32Google Scholar; Diod, . 16. 16. 2Google Scholar. The exact date of Herakleides' arrival is not given in the sources. Herakleides arrived shortly after the battle of the cross-wall. Since some months should be posited for the events from Dion's entrance to this battle, we should put Herakleides' arrival in late 357, or early 356 B.C. The numbers of his ships accepted here are those given by Diodoros (see Grote, , Hist, of Gr. [Everyman, ed.] 11. 88 with n. 2); Plut. gives 7 triremes and 3 transports; for the fleet see further below, p. 214 and n. 2.Google Scholar

page 209 note 4 See above, p. 208, n. 2.

page 210 note 1 Plut, . Dion. 28. 3–4Google Scholar; Diod, . 16. 10. 5 ff.Google Scholar; 16. 11. 2; cf. also Dion 29. 4Google Scholar; Diod, . 16. 10. 3.Google Scholar

page 210 note 2 Dion, 32. 2Google Scholar; cf. Wickert, , R.E., s.v. Syrakusai, col. 1593.Google Scholar

page 210 note 3 For details see Plut, . Dion 31Google Scholar; cf. Hackforth, , C.A.H. vi. 280 with n. 1.Google Scholar

page 210 note 4 Plut, . Dion 32. 5; cf. 52. 5–6.Google Scholar

page 210 note 5 See Plato’s words of admonition in his letter to Dion in Ep. iv. 321Google Scholar; cf. also Plut, . Dion 8. 4; 52. 5–6Google Scholar; Coriol., 15. 4Google Scholar; Moral, . 69 f–70 a.Google Scholar

page 210 note 6 Plut, . Dion 32. 2Google Scholar; cf. also Comp. Dion-Brutus 3. 7–10.Google Scholar

page 210 note 7 Plut, . Dion 34. 2Google Scholar (cf. Arist, . Pol. 1312a4–8)Google Scholar; see also ibid. 32. 1; 48. 5; Diod, . 16. 17. 3Google Scholar. Comp. Dion-Brut. 3. 10 shows that even in the circle of Dion's friends there was some thought of Dion becoming a kind of enlightened tyrant. It is worth noting that all the sources quoted are favourable to Dion.Google Scholar

page 210 note 8 See above p. 209, and n. 2.

page 210 note 9 For Dion's Platonic connections and political ideals, see Plut, . Dion 52; 53Google Scholar; cf. Plat, . Ep. 7. 334; 336Google Scholar; Plut, . Comp. Timol. Aem. Paul. 2. 1–2Google Scholar; see also Grote, , op. cit. 107 ff.Google Scholar; Pöhlmann, , Gesch. d. soz. Frage, 334 f.Google Scholar; Westlake, , op. cit. 37 f.Google Scholar

page 210 note 10 Plut, . Dion 32. 2.Google Scholar

page 211 note 1 See Diod, . 16. 6. 4Google Scholar; 16. 16. 2; Plut, . Dion 12. 1; 32. 3Google Scholar; Nep, . Dion 5. 1; 6. 3–5Google Scholar; Plat, . Ep. 4. 320 d-e; 7. 348a-349e; 3. 318c; 319a.Google Scholar

page 211 note 2 Plut, . Dion 33. 1–3.Google Scholar

page 211 note 3 Ibid. 4–5.

page 211 note 4 Plut, Dion 34 (the episode of Sosis, on which see below, p. 213), and 33. 4–5.Google Scholar

page 211 note 5 Plut, . Dion 35–6Google Scholar; Diod, . 16. 16. 3Google Scholar; Ephoros, , fr. 219 (Fr. Gr. Hist.)Google Scholar; cf. Hackforth, , 281 with n. 1.Google Scholar

page 211 note 6 Even before the sea-battle the Syracusans ‘were suspicious of the mercenaries [viz. of Dion], and especially so now that most of the struggles against the tyrant were carried on at sea … and since the mercenaries were hoplites, they thought them of no further use for the war, nay, they felt that even these troops were dependent for protection upon the citizens themselves who were seamen and derived their power from the fleet’ ![]()

![]() After the victory ‘they were even more elated’

After the victory ‘they were even more elated’ ![]()

![]() Plut, . Dion 35. 2–3Google Scholar; cf. also Diod, . 16. 17. 3.Google Scholar

Plut, . Dion 35. 2–3Google Scholar; cf. also Diod, . 16. 17. 3.Google Scholar

page 212 note 1 According to Plut, . Dion 37. 4–5Google Scholar (based on Timonides or on Timaios), after Dionysios ‘eluded the vigilance of Herakleides the admiral, and sailed off … Herakleides was stormily denounced by the citizens, whereupon he induced Hippon … to make proposals to the people …’, etc. Diod, . 16. 17. 3–4Google Scholar (based on Ephoros) does not mention this at all, and speaks of a struggle between the partisans of Dion and the followers of Herakleides over the question of supreme power in Syracuse. It is always to be kept in mind that to the two main authorities of Plutarch's Life of Dion, Herakleides is throughout the ‘villain of the piece’, and is personally responsible for all the evils which befell Syracuse. Making him responsible for the deposition of Dion out of personal spite, and for the mishaps that followed, is perfectly in line with this. It is, of course, possible that Dion's partisans tried to lay the escape of Dionysios at Herakleides' door. But it is worth noting that in Comp. Dion. Brut. 2. 31Google Scholar, in which Plutarch is much less influenced by the pro-Dion tradition (cf. Westlake, , op. cit. 38, n. 61)Google Scholar, it is Dion who is said to have been accused of letting Dionysios go. Moreover, it is quite clear that Heiakleides' popularity with the populace was not weakened to any noticeable degree, if at all, by Dionysios' escape. On the contrary, it would seem to have been rather enhanced by the victory. After all, Dionysios' despair of his chances was a direct result of Herakleides' victory. Though it is transparent that we have in Plutarch a piece of straight partisanship, it is perhaps worth noting that Herakleides' part in the naval victory is not at all mentioned in Plutarch's Dion (cf. Thiel, , op. cit. 34Google Scholar for the ![]()

![]() in Plut, . Dion 35. 3Google Scholar). Herakleides becomes in Plutarch's source ‘an admiral of the fleet’ for evil only. It would seem to be clear that Herakleides and the popular leaders resolved on bringing their struggle with Dion to a head from a position of strength, not of weakness. Cf., e.g., Beloch, , op. cit. iii. 1. 259Google Scholar; Ed. Meyer, , G. d. A. v. 517Google Scholar; the views of Plass, , Die Tyrannis, etc., ii. 252Google Scholar; Hüttl, , Verfassungsgeschichte von Syrakus (Prag, 1929), 113 f.Google Scholar; Niese, , R.E., s.v. Dion, , col. 841Google Scholar; Hackforth, , 281Google Scholar; Asheri, , Distribuzioni di terre nel l'antica Grecia (Torino, 1966), 88Google Scholar should be dismissed. This erroneous view is strongly urged also by von Scheliha, Renata, Dion; die platonische Staatsgriindung in Sizilien (Leipzig, 1934), p. 56, if, that is, one should speak at all of views with regard to an author to whom, for instance: ‘Im Sinn der Hellenen, als heroischer Täter, als göttlich verklärte Gestalt hat sich Dion erfüllt’ (p. 63). The date of publication has, possibly, something to do with the hysterics of the book.Google Scholar

in Plut, . Dion 35. 3Google Scholar). Herakleides becomes in Plutarch's source ‘an admiral of the fleet’ for evil only. It would seem to be clear that Herakleides and the popular leaders resolved on bringing their struggle with Dion to a head from a position of strength, not of weakness. Cf., e.g., Beloch, , op. cit. iii. 1. 259Google Scholar; Ed. Meyer, , G. d. A. v. 517Google Scholar; the views of Plass, , Die Tyrannis, etc., ii. 252Google Scholar; Hüttl, , Verfassungsgeschichte von Syrakus (Prag, 1929), 113 f.Google Scholar; Niese, , R.E., s.v. Dion, , col. 841Google Scholar; Hackforth, , 281Google Scholar; Asheri, , Distribuzioni di terre nel l'antica Grecia (Torino, 1966), 88Google Scholar should be dismissed. This erroneous view is strongly urged also by von Scheliha, Renata, Dion; die platonische Staatsgriindung in Sizilien (Leipzig, 1934), p. 56, if, that is, one should speak at all of views with regard to an author to whom, for instance: ‘Im Sinn der Hellenen, als heroischer Täter, als göttlich verklärte Gestalt hat sich Dion erfüllt’ (p. 63). The date of publication has, possibly, something to do with the hysterics of the book.Google Scholar

Westlake, , op. cit. 40, though not directly connecting the failure in intercepting Dionysios with the proposal for redistribution, says that Herakleides ‘was in danger of impeachment’. It is rather hard to see on what this is based. See also above, p. 208, n. 1.Google Scholar

page 212 note 2 Plut, . Dion 28. 1–2.Google Scholar

page 212 note 3 Above, p. 211.

page 213 note 1 Plut, . Dion 33. 4.Google Scholar

page 213 note 2 For ![]() see, e.g., Halic, Dion. Ant, Rom. 5. 75. 3Google Scholar; Plut, . Cim, 17. 2Google Scholar; Phoc. 16. 3Google Scholar; cf.

see, e.g., Halic, Dion. Ant, Rom. 5. 75. 3Google Scholar; Plut, . Cim, 17. 2Google Scholar; Phoc. 16. 3Google Scholar; cf. ![]()

page 213 note 3 Plut, . Dion 38. 4Google Scholar; cf. also ![]()

![]() — Diod, . 16. 17. 1.Google Scholar

— Diod, . 16. 17. 1.Google Scholar

page 213 note 4 Plut, . Dion. 38. 4–5.Google Scholar

page 213 note 5 Ibid. 44. 1–2.

page 213 note 6 Ibid. 45–6, and especially 47. 1.

page 213 note 7 Ibid. 47. 1–3.

page 213 note 8 See also the highly interesting passage in Plut, . Dion 32. 5Google Scholar: ![]() of [viz. the Syracusan populace] …

of [viz. the Syracusan populace] … ![]()

![]() Though the context is a violent attack on Herakleides, the reference is not to him only. Cf. also 47. 3.

Though the context is a violent attack on Herakleides, the reference is not to him only. Cf. also 47. 3.

page 213 note 9 Plut, . Dion 34–35. 1.Google Scholar

page 213 note 10 ![]() [viz. Herakleides]

[viz. Herakleides] ![]()

![]() Plut, . Dion 37. 5Google Scholar. Hippon is represented here as Herakleides' tool. It was allegedly Herakleides who initiated the

Plut, . Dion 37. 5Google Scholar. Hippon is represented here as Herakleides' tool. It was allegedly Herakleides who initiated the ![]() for purely personal reasons (cf. above, p. 212, n. 1), and even put to Hippon its ideological justification. That is, of course well in line with the violently anti-Herakleidean bias of Plutarch's source. Though Herakleides certainly espoused the programme of the Syracusan ‘demagogues’ (cf. Grote, , op. cit., p. 94Google Scholar), and fully collaborated with them for its implementation, it is most unlikely that he devised it. In all probability Hippon was one of the prominent leaders of the Syracusan demos, who propounded to the Assembly one of the main points of the radical programme. The proposed identification of this Syracusan politician with Hippon the tyrant of Messana (Westlake, , Timoleon and his Relations with Tyrants [Manchester, 1952] P. 51Google Scholar) nas absolutely nothing to commend it, and should be disregarded. Another anti-Dion leader known to us by name was Athanis the historian, cf. Brown, , op. cit. 19 f. But he might well have belonged to the circle of Herakleides' relatives and friends, which included also the admiral's uncle, Theodotes, and his brother.Google Scholar

for purely personal reasons (cf. above, p. 212, n. 1), and even put to Hippon its ideological justification. That is, of course well in line with the violently anti-Herakleidean bias of Plutarch's source. Though Herakleides certainly espoused the programme of the Syracusan ‘demagogues’ (cf. Grote, , op. cit., p. 94Google Scholar), and fully collaborated with them for its implementation, it is most unlikely that he devised it. In all probability Hippon was one of the prominent leaders of the Syracusan demos, who propounded to the Assembly one of the main points of the radical programme. The proposed identification of this Syracusan politician with Hippon the tyrant of Messana (Westlake, , Timoleon and his Relations with Tyrants [Manchester, 1952] P. 51Google Scholar) nas absolutely nothing to commend it, and should be disregarded. Another anti-Dion leader known to us by name was Athanis the historian, cf. Brown, , op. cit. 19 f. But he might well have belonged to the circle of Herakleides' relatives and friends, which included also the admiral's uncle, Theodotes, and his brother.Google Scholar

page 214 note 1 Plut, . Dion 37. 5.Google Scholar

page 214 note 2 The number of ships brought from Greece by Herakleides is given as 20 triremes by Diod, . 16. 16. 2Google Scholar; Plut, . Dion 32. 4Google Scholar has 7 triremes and 3 transports. The overall number of Philistos' fleet is given by Diod, . 16. 16. 3Google Scholar as 60, and of the Syracusans' as ![]() For the disbanding of the fleet, see Plut, . Dion 50. 1.Google Scholar

For the disbanding of the fleet, see Plut, . Dion 50. 1.Google Scholar

page 214 note 3 See on the ‘naval crowd’ ![]()

![]() Plut, . Dion 35. 2–3;

Plut, . Dion 35. 2–3; ![]() is here political ‘weight’, ‘influence’. The crews of the ships brought over by Herakleides from Greece could not have been, at their arrival, Syracusan, though they could have been later replaced by Syracusans.Google Scholar

is here political ‘weight’, ‘influence’. The crews of the ships brought over by Herakleides from Greece could not have been, at their arrival, Syracusan, though they could have been later replaced by Syracusans.Google Scholar

page 214 note 4 ![]() Plut, . Dion 48. 5Google Scholar (cf.

Plut, . Dion 48. 5Google Scholar (cf. ![]()

![]() ibid. 49. 1). These are, to be sure, Syracusan citizens in the Assembly. The locus classicus on the connection between the personnel of the navy and radical democracy is, of course, Ps. Xen, . Ath. Pol. 1. 2Google Scholar (cf. Fuks, , Scripta Hierosolymitana i, 1954, 25 f.).Google Scholar

ibid. 49. 1). These are, to be sure, Syracusan citizens in the Assembly. The locus classicus on the connection between the personnel of the navy and radical democracy is, of course, Ps. Xen, . Ath. Pol. 1. 2Google Scholar (cf. Fuks, , Scripta Hierosolymitana i, 1954, 25 f.).Google Scholar

page 214 note 5 ![]()

![]() Plut, . Dion 48. 5.Google Scholar

Plut, . Dion 48. 5.Google Scholar

page 214 note 6 See Polyb, . 38. 12. 5Google Scholar: ![]()

![]()

![]() (of the Achaian Assembly in 146 B.C., packed and dominated by the lower classes, which decided on war with Rome); cf. also e.g. Xen, . Oeo. 4. 2 ff.Google Scholar; Mem. 4. 2. 22 ff.Google Scholar; Plat, . Resp. 6. 495 d (with Schol.)Google Scholar; Arist, . Pol. 1258b37; 1328b39; 1337b1 1 ff.Google Scholar; Plat, . Charm. 163 bGoogle Scholar; Dion, . Halic. Ant. Rom. 3. 28Google Scholar; [Arist, .] Oec. 1. 3Google Scholar; Etym, . magn. 188. 40Google Scholar; Suidas, s.v.

(of the Achaian Assembly in 146 B.C., packed and dominated by the lower classes, which decided on war with Rome); cf. also e.g. Xen, . Oeo. 4. 2 ff.Google Scholar; Mem. 4. 2. 22 ff.Google Scholar; Plat, . Resp. 6. 495 d (with Schol.)Google Scholar; Arist, . Pol. 1258b37; 1328b39; 1337b1 1 ff.Google Scholar; Plat, . Charm. 163 bGoogle Scholar; Dion, . Halic. Ant. Rom. 3. 28Google Scholar; [Arist, .] Oec. 1. 3Google Scholar; Etym, . magn. 188. 40Google Scholar; Suidas, s.v. ![]() ; Hesych, . s.v.Google Scholar; Pollux, 1. 50; 1. 64; 7. 6Google Scholar; Stob, . 43. 93Google Scholar; Diog, . Laert. 6. 70Google Scholar; Arist, . Eth. Eud. 1215a30Google Scholar. See also, e.g., Büchsenschiitz, , Besitz und Erwerb im griechischen Altertum, 265 f.Google Scholar; Bolkestein, , Economic Life in Greece's Golden Age, 71Google Scholar; Druman, , Die Arbeiter und Communisten in Griechenland und Rom, 60Google Scholar; Newman, , The Politics of Aristotle, i. 103Google Scholar; Oertel, , Klassen-kampf, Sozialismus und organischer Staat im alten Griechenland, p. 24Google Scholar; Busolt-Swoboda, , Griech. Staatsk. i. 182 with n. 5, cf. 209, n. 1.Google Scholar

; Hesych, . s.v.Google Scholar; Pollux, 1. 50; 1. 64; 7. 6Google Scholar; Stob, . 43. 93Google Scholar; Diog, . Laert. 6. 70Google Scholar; Arist, . Eth. Eud. 1215a30Google Scholar. See also, e.g., Büchsenschiitz, , Besitz und Erwerb im griechischen Altertum, 265 f.Google Scholar; Bolkestein, , Economic Life in Greece's Golden Age, 71Google Scholar; Druman, , Die Arbeiter und Communisten in Griechenland und Rom, 60Google Scholar; Newman, , The Politics of Aristotle, i. 103Google Scholar; Oertel, , Klassen-kampf, Sozialismus und organischer Staat im alten Griechenland, p. 24Google Scholar; Busolt-Swoboda, , Griech. Staatsk. i. 182 with n. 5, cf. 209, n. 1.Google Scholar

page 214 note 7 Plut, . Dion 42. 2–4; 44. 2–3; 48. 5Google Scholar; cf. Diod, . 16. 20. 1.Google Scholar

page 215 note 1 Plut, . Dion 38. 1Google Scholar. Strictly speaking this is the date of the election of the new strategoi, which followed the Assembly in which Dion was deposed by 15 days (see Plut. Dion, ibid.).

page 215 note 2 We do not know for certain who had the right of convening the ekklesia, but it would seem that it was not only Dion, the strategos autokrator. It is said that the Syracusans chose Herakleides as admiral in an ekklesia of their own calling ![]() then, pressed by Dion, they revoked the appointment of Herakleides. This, too, must have been an Assembly convoked not by Dion, since only the third Assembly to deal with the appointment of Herakleides is specifically said to have been convoked by Dion

then, pressed by Dion, they revoked the appointment of Herakleides. This, too, must have been an Assembly convoked not by Dion, since only the third Assembly to deal with the appointment of Herakleides is specifically said to have been convoked by Dion ![]()

![]() Plut, . Dion 33. 1–3).Google Scholar

Plut, . Dion 33. 1–3).Google Scholar

page 215 note 3 The stasis of midsummer 356 B.C. is also referred to in Diod, . 16. 17. 3Google Scholar, but the Assembly is not specifically mentioned. The second Assembly is alluded to in Diod, . 16. 20. 6Google Scholar, but in such vague terms that no real information can be derived from the passage.

page 215 note 4 See above, p. 208, n. 1 and also p. 212,. n. 1.

page 215 note 5 By Herakleides personally, according to the version in Plutarch's Dion.

page 216 note 1 Plut, . Dion 38Google Scholar; Theopompus, fr. 194 (Fr. Gr. Hist.) cf. also Dion 47. IGoogle Scholar (from which it might perhaps be gathered that Theodotes, the uncle of Herakleides, was one of the strategoi, and Diod, . 16. 17. 3–5Google Scholar (who tells of Dion's exit, but does not expressly mention the election). The postponement of the election for fifteen days is said to have been caused by unfavourable omens, which prevented the convening of an archairesiai assembly (Plut, . Dion 38Google Scholar). On Athanis see Theopompos, , loc. cit.Google Scholar The attempt of the popular leaders to bring over Dion's mercenaries to the Syracusans' side by promise of citizenship failed. The promises probably included getting allotments in the redistribution; cf. Freeman, , A History of Sicily, iv. 267.Google Scholar

page 216 note 2 I refer to the recent study of Asheri, D., Distribuzioni di terre nell'antica Grecia (Torino, 1966), Chaps. II-IV for reference with regard to ![]() and for discussion of cases known under the heads specified above.Google Scholar

and for discussion of cases known under the heads specified above.Google Scholar

page 217 note 1 Types (a) and (A) are, to be sure, not mutually exclusive. In some cases both creating of equality and enlarging of the citizen-body, to strengthen the state, are declared aims. A good example is the revolution of Agis and Kleomenes in Sparta; see Fuks, , C.P. lvii (1962), 161 ffGoogle Scholar. and Athenaeum, x (1962), 244 ff.Google Scholar, cf. also C.Q. N.s. xii (1962), 118 ff. When there is a comprehensive anaplerosis, a redivision of the entire territory follows on the basis of ![]() whether equality in landed property is a declared object or not.Google Scholar

whether equality in landed property is a declared object or not.Google Scholar

page 217 note 2 Ortygia was still—it was hoped in Syracuse not for long—occupied by Dionysios' force. Its territory, too, was, to be sure, destined for redivision in due course.

page 217 note 3 That seems also to be the view of Asheri, , op. cit. 88 ff.Google Scholar, but it is obscured by the stress he lays on the importance of Ortygia, still in occupation of the tyrant, and of the estates of the tyrant and his friends in the plain of Heloros. Ortygia, though of importance with regard to housing, was negligible from the point of view of cultivation; cf. Stroheker, , Dionysios I, 52Google Scholar; Holm, , Gesch. Siciliens i. 122 f. With regard to the plain of Heloros, there was no need to defer redivision until the final expulsion of the tyrant's garrison in Ortygia.Google Scholar

page 217 note 4 See ![]()

![]() Syll.3 526.] 11. 21 ff. (Itanos, early third century B.C.), cf. also Syll.3 141 (from Cercyra Nigra, early fourth century B.C.), which possibly also dealt with

Syll.3 526.] 11. 21 ff. (Itanos, early third century B.C.), cf. also Syll.3 141 (from Cercyra Nigra, early fourth century B.C.), which possibly also dealt with ![]()

![]() though the formula does not occur in full; see Asheri, , op. cit. 22Google Scholar. (It is worth noting that settlers invited by Timoleon from Greece to Syracuse were promised

though the formula does not occur in full; see Asheri, , op. cit. 22Google Scholar. (It is worth noting that settlers invited by Timoleon from Greece to Syracuse were promised ![]() Diod, . 16. 82. 5Google Scholar; see also Plut, . Timol. 23. 6 where houses are said to have been cheaply provided, option being given to former owners.)Google Scholar

Diod, . 16. 82. 5Google Scholar; see also Plut, . Timol. 23. 6 where houses are said to have been cheaply provided, option being given to former owners.)Google Scholar

page 217 note 5 Plut, . Dion 41Google Scholar; cf. Diod, . 16. 18. 1–3.Google Scholar

page 218 note 1 Dion 48. 3–6Google Scholar; cf. Diod, . 16. 20. 6.Google Scholar

page 218 note 2 The date of the Assembly cannot be exactly fixed; Westlake's spring 355 B.C. (Durham Univ. Journ., p. 41) is a guess.Google Scholar

page 218 note 3 Cf. Westlake, , op. cit. 41Google Scholar on Dion's increasing reliance on military force; for his autocratic rule see Grote, , op. cit. 103 ff.Google Scholar; Bury, , A History of Greece 3, 672Google Scholar; Westlake, , loc. cit. 41Google Scholar; id. Cambr. Hist. Journ. vii (1941–1943), 77 f. After his restoration he ruled without an Assembly, with a kind of private council only.Google Scholar

page 218 note 4 See for them Asheri, , op. cit. Chap. IV.Google Scholar

page 218 note 5 Such are, prominently, the cases of Agis and KJeomenes. Cf. the papers quoted in p. 217, n. 1.

page 219 note 1 Cf., e.g., Grote, , op. cit. 94Google Scholar; Glotz, , Ancient Greece at Work (Eng. transl.), 157Google Scholar; Hackforth, , op. cit. 281Google Scholar; Loenen, , Stasis 13.Google Scholar

page 219 note 2 Aekenaum viii (1930), 295 f.Google Scholar; 279 with n. 2 (read Ippone, for Itone).

page 219 note 3 Op. cit. i. 327.Google Scholar

page 219 note 4 Op. cit. 89 ff.Google Scholar

page 219 note 5 Cf., e.g., [Demosth, .] 58. 19Google Scholar; Plut, . Them. 8Google Scholar; Plat, . Resp. 564 aGoogle Scholar; Leg. 699 cGoogle Scholar; Menex. 239 aGoogle Scholar; Plut, . Timol. 22. 1–2Google Scholar; Comp. Sol.Public. 3. 1Google Scholar; Plb, . 18. 47. 7Google Scholar; 25. 5. 3; Thuc, . 1. 69Google Scholar; 4. 114. 3; Arist, . Pol. 1291b34; 1296b18; 1294a11, 20; see also above, p. 209, n. 2.Google Scholar

page 219 note 6 For references to political connotation of ‘equality’ see Vlastos, , ‘Isonomia’ A.J.P. lxxiv (1953), 337 ffGoogle Scholar. For ![]() as an economic concept see, for instance, Arist, . Pol. 1265a38–b16; 1266a37-b4Google Scholar; 1266b14sqq.; 1267b9–19; Plat. Leg. 684 d; 741 a-b, cf. 744 a-b; Plut, . Ag. 5. 2–3Google Scholar; and for fuller references Asheri, , op. cit. 60 ff.; 78 ff.; 103 ff. See also p. 222, n. 1 with sources quoted there.Google Scholar

as an economic concept see, for instance, Arist, . Pol. 1265a38–b16; 1266a37-b4Google Scholar; 1266b14sqq.; 1267b9–19; Plat. Leg. 684 d; 741 a-b, cf. 744 a-b; Plut, . Ag. 5. 2–3Google Scholar; and for fuller references Asheri, , op. cit. 60 ff.; 78 ff.; 103 ff. See also p. 222, n. 1 with sources quoted there.Google Scholar

page 219 note 7 Cf., e.g., Arist, . Vesp. 602Google Scholar; Plat, . Epist. 8. 354 eGoogle Scholar; Soph, . Ajax 944Google Scholar; Eur, . Bac. 803Google Scholar; Plat, . Leg. 699 eGoogle Scholar; Resp. 564 aGoogle Scholar; 469 c; Thuc, . 1. 8. 3Google Scholar; 1. 122. 2; Plb, . 11. 12. 3Google Scholar; 9. 28. 1; Arist, . Pol. 1264a36. On nexi for debt in Syracuse itself, on the accession of Dionysios IIGoogle Scholar, see Justin, 21. 1. 5Google Scholar; 21. 2. (For some aspects of ‘living at the disposal of another’, which was a mark of slavery, cf. Newman, , op. cit. i. 103Google Scholar and Arist, . Pol. 1260a33; Rhet. 1367a3).Google Scholar

page 220 note 1 Strictly speaking, it is not ![]() which is incompatible with

which is incompatible with ![]() —a condition in which everyone is poor is perfectly compatible with equality of possession—but the existence of poverty alongside riches. It is the condition of

—a condition in which everyone is poor is perfectly compatible with equality of possession—but the existence of poverty alongside riches. It is the condition of ![]() from which results slavery for the poor, not poverty per se. Plutarch appears to be saying:

from which results slavery for the poor, not poverty per se. Plutarch appears to be saying: ![]() for everyone in general;

for everyone in general; ![]() for those who have no possessions—which makes sense if we take him to mean by

for those who have no possessions—which makes sense if we take him to mean by ![]() equality of possession in land and to imply by

equality of possession in land and to imply by ![]() a condition in which some people are poor and others rich (not a condition in which everyone is poor, for that is perfectly compatible with equality of possession in land). In other words: give everyone the same, and everyone will be free because no one will be rich enough to treat as a slave the man who is poor; if you do not give everyone the same, the result is slavery for the poor, because there will be some who are rich. See, for the question of ‘poverty versus riches’ in the revolution of Agis and Kleomenes, , C.P. lvii (1962), 163 f.Google Scholar; for some collection of passages see Manen,

a condition in which some people are poor and others rich (not a condition in which everyone is poor, for that is perfectly compatible with equality of possession in land). In other words: give everyone the same, and everyone will be free because no one will be rich enough to treat as a slave the man who is poor; if you do not give everyone the same, the result is slavery for the poor, because there will be some who are rich. See, for the question of ‘poverty versus riches’ in the revolution of Agis and Kleomenes, , C.P. lvii (1962), 163 f.Google Scholar; for some collection of passages see Manen, ![]() en

en ![]() in de periode na Alexander (Zutphen, 1931). A historical study of

in de periode na Alexander (Zutphen, 1931). A historical study of ![]()

![]() is yet to be written.Google Scholar

is yet to be written.Google Scholar

page 220 note 2 Cf. above, p. 210.

page 221 note 1 Whether or not the deposition of Dion was also justified in the ekklesia on grounds of principle we do not know. At any rate, no such justification has been preserved. Consequently, the sources collected by Asheri, , p. 91, n. 1, to throw light on some such justification have little relevance to the passage under discussion here.Google Scholar

page 221 note 2 For an attempt at morphology, as well as for a general account of the phenomenon, see my ‘Social Revolution in Greece in the Hellenistic Age’, La parola del passato, cxi (1966), 137 ff., on which this paragraph is based.Google Scholar

page 222 note 1 The remaking of Sparta was conceived by Agis and by Kleomenes as basing the life of the Spartan body-politic on ![]() Equality was to be the result of their reforms. The establishment of equality in Sparta was sometimes represented by Agis and by Kleomenes as a ‘return to Lykourgos’. They opted for ‘abolition of wealth, and putting poverty aright’, and Kleomenes is said to have wanted to lead Sparta, after it has become a city of equality

Equality was to be the result of their reforms. The establishment of equality in Sparta was sometimes represented by Agis and by Kleomenes as a ‘return to Lykourgos’. They opted for ‘abolition of wealth, and putting poverty aright’, and Kleomenes is said to have wanted to lead Sparta, after it has become a city of equality ![]() to hegemony in Greece. See for sources and discussion my paper ‘Agis, Cleomenes, and Equality’, C.P. lvii (1962), 161 ff.Google Scholar, cf. also Athenaeum xl (1962), 244 ff.Google Scholar, C.Q. N.s. xii (1962), 118 ff.Google Scholar

to hegemony in Greece. See for sources and discussion my paper ‘Agis, Cleomenes, and Equality’, C.P. lvii (1962), 161 ff.Google Scholar, cf. also Athenaeum xl (1962), 244 ff.Google Scholar, C.Q. N.s. xii (1962), 118 ff.Google Scholar

A declamation of Quintilian (Declam. cclxi) shows that the question of equality must have been often thrashed out in Greek public life, as it is undoubtedly based on topoi from Greek experience.Google Scholar

In the early period of revolutionary turmoil, in the seventh and sixth centuries, some ideological discussion of equality is known with regard to the work of Solon (see Asheri, , op. cit. 78 ff.).Google Scholar

page 222 note 2 A discussion of the Greek thought on the problem of equality will be given in my book ‘A History of the Social Conflict in Late Classical and Hellenistic Greece’, now in preparation. Valuable remarks are to be found in Asheri, , op. cit., pp. 60 ff.; 78 ff.; 103 ff.Google Scholar

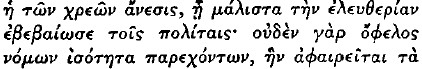

page 222 note 3 There is some similarity between the passage in Plut, . Dion 37Google Scholar and an appreciation of Solon‘s remission of debts preserved in Comp. Sol.-Publicol. 3. 1Google Scholar: ![]()

![]() However,

However, ![]() is here political equality,

is here political equality, ![]() is the freedom of a man to make use of his equal political rights, and this is to be safeguarded not by equalization of landed and real property, but by remission of debts. (The idea is not expressly attributed to Solon himself; cf. Asheri, , op. cit., p. 80 n. 4Google Scholar. It cannot be said with certainty wherefrom it stems). An interesting, though only partial, parallel to our text is to be found in Plut, . Ag. 5. 5. In describing the evil plight of Sparta on the eve of Agis' revolution, Phylarchus says:

is the freedom of a man to make use of his equal political rights, and this is to be safeguarded not by equalization of landed and real property, but by remission of debts. (The idea is not expressly attributed to Solon himself; cf. Asheri, , op. cit., p. 80 n. 4Google Scholar. It cannot be said with certainty wherefrom it stems). An interesting, though only partial, parallel to our text is to be found in Plut, . Ag. 5. 5. In describing the evil plight of Sparta on the eve of Agis' revolution, Phylarchus says: ![]()

![]()

![]() Whether he has been influenced by the fuller and more developed idea propounded in Syracuse in 356 B.C. cannot be said. At any rate, the socialeconomic situation of Sparta in mid-third century and of Syracuse in mid-fourth century was not dissimilar.Google Scholar

Whether he has been influenced by the fuller and more developed idea propounded in Syracuse in 356 B.C. cannot be said. At any rate, the socialeconomic situation of Sparta in mid-third century and of Syracuse in mid-fourth century was not dissimilar.Google Scholar

- 4

- Cited by