No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 March 2018

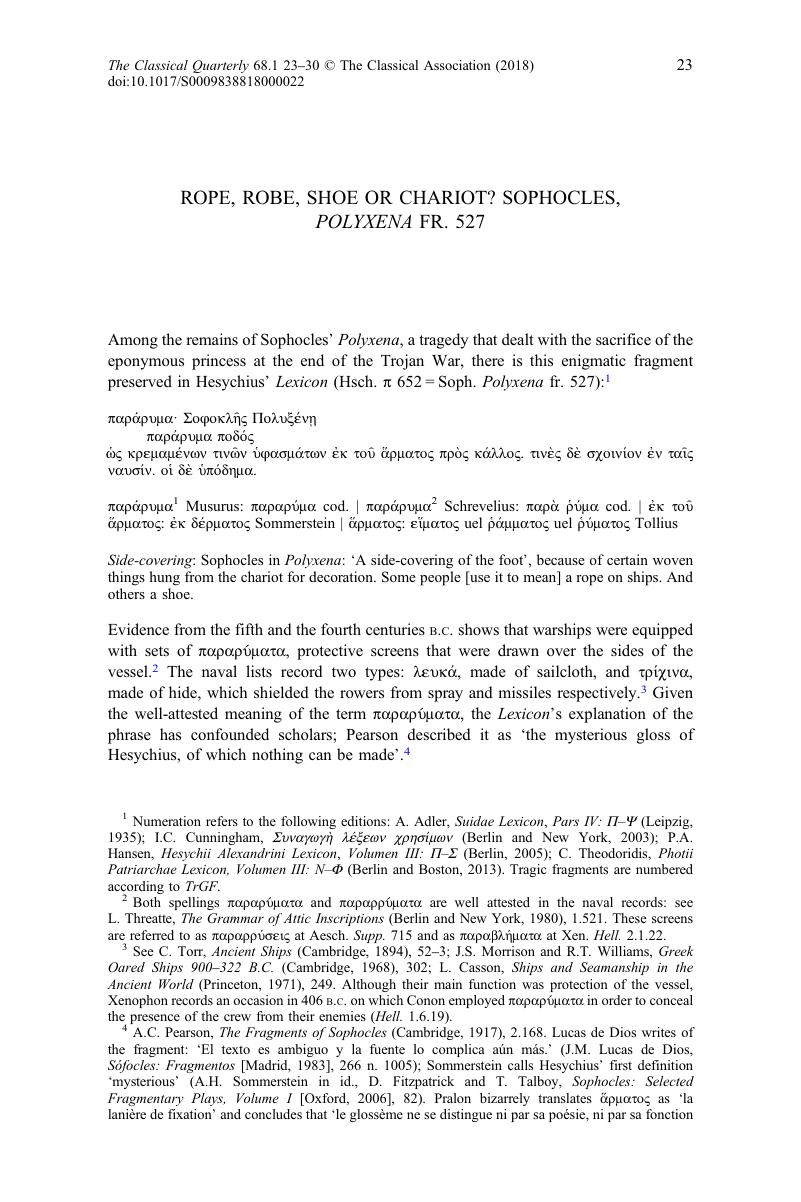

1 Numeration refers to the following editions: Adler, A., Suidae Lexicon, Pars IV: Π–Ψ (Leipzig, 1935)Google Scholar; Cunningham, I.C., Συναγωγὴ λέξεων χρησίμων (Berlin and New York, 2003)Google Scholar; Hansen, P.A., Hesychii Alexandrini Lexicon, Volumen III: Π–Σ (Berlin, 2005)Google Scholar; Theodoridis, C., Photii Patriarchae Lexicon, Volumen III: N–Φ (Berlin and Boston, 2013)Google Scholar. Tragic fragments are numbered according to TrGF.

2 Both spellings παραρέματα and παραρρέματα are well attested in the naval records: see Threatte, L., The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions (Berlin and New York, 1980), 1.521Google Scholar. These screens are referred to as παραρρύσεις at Aesch. Supp. 715 and as παραβλήματα at Xen. Hell. 2.1.22.

3 See Torr, C., Ancient Ships (Cambridge, 1894), 52–3Google Scholar; Morrison, J.S. and Williams, R.T., Greek Oared Ships 900–322 B.C. (Cambridge, 1968), 302Google Scholar; Casson, L., Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World (Princeton, 1971), 249Google Scholar. Although their main function was protection of the vessel, Xenophon records an occasion in 406 b.c. on which Conon employed παραρέματα in order to conceal the presence of the crew from their enemies (Hell. 1.6.19).

4 Pearson, A.C., The Fragments of Sophocles (Cambridge, 1917), 2.168Google Scholar. Lucas de Dios writes of the fragment: ‘El texto es ambiguo y la fuente lo complica aún más.’ (Lucas de Dios, J.M., Sófocles: Fragmentos [Madrid, 1983], 266 n. 1005Google Scholar); Sommerstein calls Hesychius’ first definition ‘mysterious’ (A.H. Sommerstein in id., Fitzpatrick, D. and Talboy, T., Sophocles: Selected Fragmentary Plays, Volume I [Oxford, 2006], 82Google Scholar). Pralon bizarrely translates ἅρματος as ‘la lanière de fixation’ and concludes that ‘le glossème ne se distingue ni par sa poésie, ni par sa fonction dramatique … Il paraît simplement relever d'une langage métaphorique, plutôt recherché, voire apprêté.’ (Pralon, D., ‘La Polyxène de Sophocle’, in Fartzoff, M., Faudot, M., Geny, E. and Guelfucci, M.-R. [edd.], Reconstruire Troie: Permanence et renaissances d'une cité emblématique [Besançon, 2009], 187–208Google Scholar, at 203–4).

5 This point is missed by Ellendt, F., Lexicon Sophocleum (Berlin, 1872 2), 602 s.vGoogle Scholar. παράρυμα, who takes all three definitions to be confusingly variant explanations of the Sophoclean phrase, commenting: ‘ex quibus haec hausit lexici conditor, eos Sophoclis fabulam non amplius legisse integram manifestum est: non potuissent enim dubitare pes hominisne an nauis intelligendus esset, nec de instita et calceo ambigere.’

6 Alberti's edition reports three conjectures by Toll for Hesychius’ ἅρματος: εἵματος, ῥάμματος and ῥύματος, with the explanation of the Sophoclean phrase as ‘pars uestis, quae trahebatur’; it is not clear what meaning of ῥῦμα is understood here (Alberti, J., Hesychii Lexicon, Tomus Secundus [ed. Ruhnken, D.] [Leiden, 1766], 868Google Scholar).

7 The Cyril lexicon (as reported by Cunningham [n. 1] from the unpublished edition of A.B. Drachmann), Synagoge π 139, Phot. π 290 and Suda π 425 all include the entry παραρέματα (παραρρ- Su. G, –μμ– Syn. A, Phot., Su.)· δέρρεις (–ρ– Phot., Su.), σκεπάσματα (om. Cyr. A).

8 εἵματος is printed by, for example, Dindorf, W., Poetae scenici Graeci (Leipzig and London, 1830), 53Google Scholar (Ἀποσπασμάτια) and Ahrens, E.A.J., Sophoclis fragmenta (Paris, 1844), 280Google Scholar. It is also accepted by Ellendt (n. 5), 602, who believed the object in question to be the trailing hem of a garment. ῥάμματος is noted with approval by Schmidt, M., Hesychii Alexandrini Lexicon, Volumen Tertium: Λ–Ρ (Jena, 1861), 276Google Scholar, and printed in the text of Hesychius by Hansen (n. 1).

9 Welcker, F.G., Die griechischen Tragödien mit Rücksicht auf den epischen Cyclus (Bonn, 1839–1841), 178Google Scholar; see also Ahrens (n. 8), 280.

10 See Pearson (n. 4), 2.167–8; Calder, W.M., ‘A reconstruction of Sophocles' Polyxena’, GRBS 7 (1966), 31–56Google Scholar, at 49 (reprinted in id., Theatrokratia: Collected Papers on the Politics and Staging of Greco-Roman Tragedy [ed. Smith, R.S.] [Hildesheim, Zürich and New York, 2005], 233–66Google Scholar, at 256–7); Sommerstein (n. 4), 81.

11 For the theme in tragedy, see Aesch. Edoni fr. 59 ὅστις χιτῶνας βασσάρας τε Λυδίας | ἔχει ποδήρεις (of Dionysus); Eur. Bacch. 833 πέπλοι ποδήρεις (of Maenad dress).

12 However, the anonymous reviewer for CQ suggests that fr. 527 comes from a description of Agamemnon's royal robes, thus foreshadowing the garment in which he will be killed. If so, his clothing would have been unusual for a Greek man, with the covering of the feet perhaps intended as an orientalizing effect.

13 U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ms. ap. Radt, S.L., Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, Vol. 4: Sophocles (Göttingen, 1999 2), 407CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See also Hartung, J.A., Sophokles’ Werke. Achtes Bändchen: Fragmente (Leipzig, 1851), 50Google Scholar, who suggests that the fragment refers to the robe worn by Polyxena at her sacrifice.

14 Sommerstein (n. 4), 242–3.

15 cf. Il. 18.353 ἐς πόδας ἐκ κεφαλῆς (of Patroclus’ funeral garment), and see Seaford, R., ‘The last bath of Agamemnon’, CQ 34 (1984), 247–54CrossRefGoogle Scholar, at 252.

16 Sommerstein (n. 4), 82.

17 Sommerstein (n. 4), 75.

18 This does not, however, take into account the fact that the leather sets of παραρέματα were not woven (ὑφασμάτων), and that the woven (i.e. sailcloth) sets of παραρέματα were not made of leather.

19 See also Soph. Captivae fr. 44 πατὴρ δὲ †χρυσυσδύς† ἀμφίλινα κρούπαλα, which Pearson (n. 4), 1.31–2 suggested might refer to ‘the elaborately fashioned shoes of the oriental monarch [i.e. Priam] with their decoration of gold’.

20 Ellendt (n. 5), 602 incorrectly reports Photius’ definition of παραρέματα as δέρρεις, ὑποδήματα, an error perhaps prompted by his quotation of Phot. π 289 immediately beforehand. The correct text is δέρρεις, σκεπάσματα (see n. 7). For an exhaustive survey of fifth-century and fourth-century Greek terms for footwear, see Bryant, A.A., ‘Greek shoes in the classical period’, HSPh 10 (1899), 57–102Google Scholar.

21 Campbell, L., Sophocles (Oxford, 1881), 2.527Google Scholar.

22 The scholiast's interpretation is accepted by, for example, Bryant (n. 20), 75; Barrett, W.S., Euripides: Hippolytos (Oxford, 1964), 380Google Scholar; Harris, H.A., ‘The foot-rests in Hippolytus’ chariot’, CR 18 (1968), 259–60Google Scholar.

23 None the less, the alternative explanation of the Euripidean phrase αὐταῖσιν ἀρβέλαισιν—that Hippolytus leaps into his chariot ‘boots and all’ (accepted by, for example, Paley, F.A., Euripides, with an English Commentary [London, 1872], 1.233Google Scholar and LSJ s.v. ἀρβύλη)—is rightly dismissed by Barrett (n. 22), 380 as ‘silly’.

24 We find a protective apron of this kind on a few Cypriot Iron Age terracotta representations of chariots, while some Cypriot stone models of the same period seem to indicate a cloth draped over the siding. See Crouwel, J.H., ‘Chariots in Iron Age Cyprus’, Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus (1987), 101–18Google Scholar, at 105, reprinted in Littauer, M.A. and Crouwel, J.H., Selected Writings on Chariots and Other Early Vehicles, Riding and Harness (ed. Raulwing, P.) (Leiden, Boston and Cologne, 2002), 141–73Google Scholar, at 150.

25 For this description of the high-front chariot, see Crouwel, J.H., Chariots and Other Wheeled Vehicles in Iron Age Greece (Amsterdam, 1992), 30–3Google Scholar.

26 Il. 5.727–8, 10.475, 23.335, 23.436. See Lorimer, H.L., Homer and the Monuments (London, 1950), 326Google Scholar.

27 See the edition and discussion of Mülke, C., ‘4807. Sophocles’, ΕΠΙΓΟΝΟΙ’, The Oxyrhynchus Papyri 71 (2007), 15–26Google Scholar.

28 Brown, S.G., ‘A contextual analysis of tragic meter: the anapest’, in D'Arms, J.H. and Eadie, J.W. (edd.), Ancient and Modern Essays in Honor of Gerald F. Else (Ann Arbor, 1977), 45–77Google Scholar.

29 Sommerstein (n. 4), 82.

30 Taplin, O., The Stagecraft of Aeschylus: The Dramatic Use of Exits and Entrances in Greek Tragedy (Oxford, 1977), 76Google Scholar. Triptolemus’ chariot must have played an important role in the eponymous play by Sophocles (cf. the description of it at Soph. Triptolemus fr. 596), but it may not have appeared onstage; see Sommerstein, A.H. and Talboy, T.H., Sophocles: Selected Fragmentary Plays, Volume II (Oxford, 2012), 231Google Scholar n. 59.

31 The presence of both Atreidae in this play is attested by Strabo 10.3.14 (= Polyxena fr. 522).

32 For James Diggle's unpublished emendation, see L.M.-L. Coo, ‘Sophocles’ Trojan fragments: a commentary on selected plays’ (Diss., University of Cambridge, 2011), 180–3.

33 See Gruppe, O.F., Ariadne: die tragische Kunst der Griechen in ihrer Entwickelung und in ihrem Zusammenhang mit der Volkspoesie (Berlin, 1834), 595Google Scholar; U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ms. ap. Radt (n. 13), 406; Pearson (n. 4), 2.163; Calder (n. 10 [1966]), 46–7 = Calder (n. 10 [2005]), 253–4; Sommerstein (n. 4), 60–1.

34 If Hesychius (or, more probably, his source) was aware that the phrase referred to a specific chariot in Polyxena, this might explain why his gloss refers to ‘the’ chariot (τοῦ ἅρματος) rather than to ‘chariots’ in general. On the significance of the chariot in Agamemnon, see Himmelhoch, L., ‘Athena's entrance at Eumenides 405 and hippotrophic imagery in Aeschylus's Oresteia’, Arethusa 38 (2005), 263–302CrossRefGoogle Scholar, who demonstrates that in this play chariot imagery is associated with ‘acts of impiety, brutality, and civic injury, either performed or led by Agamemnon’ (280), as well as with aristocratic wealth, tyranny and nuptial ritual.

35 Taplin (n. 30), 304–6.

36 cf. Aesch. Ag. 905–7 νῦν δέ μοι, φίλον κάρα, | ἔκβαιν’ ἀπήνης τῆσδε, μὴ χαμαὶ τιθεὶς | τὸν σὸν πόδ’, ὦναξ, Ἰλίου πορθήτορα, and Agamemnon's description of his shoes as πρόδουλον ἔμβασιν ποδός (Ag. 945). See Levine, D.B., ‘Acts, metaphors, and powers of feet in Aeschylus's Oresteia’, TAPA 145 (2015), 253–80Google Scholar, who argues for the importance of shod and unshod feet as a strand of meaningful imagery throughout the trilogy.

37 An eloquent statement of this approach to fragments may be found in Wright, M., The Lost Plays of Greek Tragedy. Volume 1: Neglected Authors (London and New York, 2016), xxviGoogle Scholar: ‘Wherever possible, we should try to come up with alternative or multiple interpretations of the fragments. (…) It is up to us how much credulity or scepticism to adopt with regard to the evidence, but we should avoid dogmatism or dogged adherence to any one particular interpretation, for the nature of the material is such that our conclusions can only ever be tentative or provisional. Rather, we need to be exploratory and open-minded to different possibilities.’

38 This paper develops an argument originally presented in my PhD thesis (Coo [n. 32]). I am grateful to James Diggle for his guidance at the time, and to the anonymous reviewer for CQ for their comments on this material.