Article contents

Virgil's Theodicy

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

In his valuable contribution to the Fondation Hardt Entretiens of 1960 on Hesiod Professor La Penna dealt with the famous ‘theodicy of labour’ in Virgil, Georgics I. 118–59. He recalled that, whereas Hesiod made Prometheus' trickery the reason for Zeus' hiding fire and the other goods and so rendering labour necessary, Virgil omits mention of Prometheus or of any element of guilt (121–4):

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1963

References

page 75 note 1 Hésiode el son influence, Entretiens sur l'antiquité classique, tome vii, pp. 215–70. Fondation Hardt, Geneva, 1962.Google Scholar

page 75 note 2 pp. 238–9.

page 75 note 3 pp. 258–9; 261.

page 75 note 4 pp. 259–60. Cf. Bayet, J., Rev. Phil., III Sér., iv (1930), p. 238Google Scholar; Lunenborg, J., Das philosophische Weltbild in Vergils Georgica (Diss. Münster, 1935), p. 41Google Scholar; cf. 49.

page 75 note 5 I am grateful to Mr. F. H. Sandbach for valuable criticisms and suggestions.

page 75 note 6 The Prometheus story is one version of a myth, probably Semitic in origin, in which the anger of the god is due to someone's setting up as a rival to himself and imparting to others the divine prerogative. In the Hebrew version (Gen. iii) the Serpent plays the role of Prometheus. ‘And the Serpent D.-K. said unto the woman, “Ye shall not surely die; for God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”’ And the penalty is not only loss of Eden (lest man, usurping the other great prerogative of God, eat of the Tree of Life and live for ever), but the ordinance ‘in the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread’. Like-wise in the version of the Prometheus legend in the Theogony (533–4) Zeus is angry because the Titan has contested as a rival to himself. See Headlam, W., ‘Prometheus and the Garden of Eden’, C.Q. xxviii (1934), 63–71CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Lovejoy, A. O. and Hoas, G., Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity (1935), p. 192.Google Scholar

page 75 note 7 Iambl, . Vit. Pyth. 28. 139; Xen., fr. 3 D.-K.Google Scholar

page 76 note 1 The Great Chain of Being (1948), pp. 50–52.Google Scholar

page 76 note 2 Ti. 29d ff.; esp. 41 b f.

page 76 note 3 In Augustine, Dionysius the Areopagite, the Neoplatonists, Abelard, Aquinas, Dante, Leibniz, William King. See Lovejoy, A. O., op. cit., passim.Google Scholar

page 76 note 4 Entretiens, pp. 259, 186–8.Google Scholar

page 76 note 5 See esp. Pol. 267–74; Legg. 676–82 a.

page 76 note 6 Cf. Virgil's impatience with the shepherd who refuses to apply scientific remedies to his animals' sores, but sits praying to the gods for improvement, G. 3. 454–6.

page 77 note 1 P. V. 458–522.Google Scholar When Diogenes wished to return to a state of nature he abjured fire, eating cuttle-fish raw: Plut. Mor. 995 C-D.Google Scholar

page 77 note 2 321. Cf. Apollod. 1. 3. 6.

page 77 note 3 Fire = philosophy, Theophr. fr. 50 Wimmer. Prometheus is named as the first philosopher in Cicero, , Tusc. 5.3.8Google Scholar; Aug. Civ. Dei, 18. 8.Google Scholar

page 77 note 4 Virgil likes to recall the divine origin of agricultural instruments—‘Eleusinae matrix uoluentia plaustra’; ‘mystica uannus Iacchi.

page 77 note 5 Perhaps Democritus had the same idea

page 77 note 6 Strabo 15. 1. 64.

page 77 note 7 pp. 258–9; cf. Grimal on p. 261.

page 77 note 8 Gell, . N.A.7. I. 4 and 5Google Scholar; Sen. Ep. 124. 19; Plut. Sto. Rep. 37 A; Arnim, J. von, S.V.F. ii. 1183Google Scholar; Arnold, E. V., Roman Stoicism (1911), pp. 203, 206–9.Google Scholar

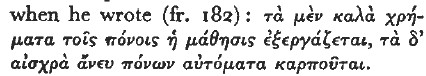

page 77 note 9 Arnim, J. von, S.V.F. ii. 1152, 1183, 1181 (l. 23), 1172.Google Scholar Democritus (fr. 154) held up certain animals, e.g. spiders, as teachers of men. But he also denied (fr. 175) that the ![]()

page 77 note 10 Epict. Diss. I. 24. 1Google Scholar; Sen. Dial. I. 2. 6; cf. 4, 7.Google Scholar

page 77 note 11 Reinhardt, K., R.-E. s.v. Poseidonios, Kapwourai. 807–8.Google Scholar Cf. Cic. de Rep. 3. 2Google Scholar; Sen. Ep. 90. 7–26.Google Scholar

page 78 note 1 Saturni filius to translate ![]() : Liv. Andr. fr. 2.

: Liv. Andr. fr. 2.

page 78 note 2 Aen. 8. 319–58Google Scholar; cf. 7. 49, 180, 203.

page 78 note 3 Macr. Sat. 7. 6. 19–26Google Scholar, apparently following Protarchus of Tralles. Cf. Dion, . Hal. Ant. Rom. I. 38. 1.Google Scholar

page 78 note 4 Varro, , L.L. 5. 64Google Scholar; rightly, it seems.

page 78 note 5 332–64.

page 78 note 6 I cannot agree with Altevogt, H., Labor improbus (1952), pp. 10–11 and n. 12, that Virgil's love belongs to the blessed, easy existence of the Saturnian Age.Google Scholar

page 78 note 7 Of course he had the Prometheus story in mind, but he made Jupiter hide fire, not in heaven, but in flint (135), ut silicis uenis abstrusum excuderet ignem, as Grimal noted in the discussion at the Entretiens (260).

page 78 note 8 Cf. Sellar, W. Y., Virgil (1877), p. 246.Google Scholar

page 78 note 9 p. 261.

page 78 note 10 It could, however, be an ![]() . Mr. Sandbach reminds me that

. Mr. Sandbach reminds me that ![]() was a watchword of Antisthenes, and Heracles a Stoic hero.

was a watchword of Antisthenes, and Heracles a Stoic hero.

page 79 note 1 His Jupiter is the Zeus of Cleanthes and Aratus, not the chief of the Olympians. It is noteworthy that, whereas Varro in the exordium to his De Re Rustica (I. I. 5Google Scholar) had included Jupiter at the head of his list of twelve deities of agriculture invoked, Virgil omitted him from his variant twelve, pre sumably because he felt he belonged to a different order: they belonged to mythology; Jupiter the Father belonged to philosophic religion, and was therefore reserved for this passage. Note too the juxtaposition ‘nocuit. Pater’.

page 79 note 2 See Waszink's, remarks, Entretiens, p. 263.Google Scholar

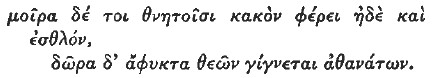

page 79 note 3 In a different context Solon (1.41–62 D.3) details the various crafts to which penury drives men, as Professor Dover reminds me. His comment is (63–64):

He is clearly sceptical about the value of it all, emphasizing the dangers, disappointments, and frustrations here and there during the catalogue and very definitely in the lines that follow (65–76).

page 79 note 4 Entretiens, p. 239.Google Scholar

page 79 note 5 I. 129–45.

page 80 note 1 P.V. 454–68.Google Scholar

page 80 note 2 ‘Glory be to God for dappled things …’.

page 80 note 3 For acorns and honey (or rather honey-dew) as the food of the Golden Age cf. Tib. I. 3, 45; Hor. Epod. 16. 47Google Scholar; Ov. Am. 3. 8. 40Google Scholar; M. I. 106, 112. For ploughing as begun in the Silver Age, Ov. M. I. 123–4. ForGoogle Scholar

parodies of the Golden Age in Greek Comedy see Ath. 6. 267.

page 80 note 4 At I. 7–8, it is Ceres' boon that corn has superseded acorns. ‘Le siècle du gland est passé, vous donnerez du pain aux homines’; Voltaire, letter to M. de la Chalotais, 3 Nov. 1762.

page 81 note 1 See Büchner, K., R.-E., s.v. P. Vergilius Maro, col. 250.Google Scholar

page 81 note 2 I 56–59.

page 81 note 3 39. Buchner, , op. cit. 247.Google Scholar

page 81 note 4 9–176. Cf. Dion, . Hal. Ant. Rom. I. 36Google Scholar; Buchner, , op. cit., 259–61, 296.Google Scholar

page 81 note 5 2. 516–22.

page 81 note 6 Lovejoy, , op. cit., pp. 76–77.Google Scholar

page 81 note 7 Lucr. 5. 925–1456Google Scholar; Diod. I. 8. 11–12Google Scholar; Hor. S. I. 3. 99–106Google Scholar; Ps.-Lucian, , Amor. 34.Google Scholar The Orphics too seem to have conceived of primitive man as brutish: fr. p. 182 Abel.

page 82 note 1 933–44; 1416.

page 82 note 2 5. 1361–78.

page 82 note 3 5. 1448–57.

page 83 note 1 For a good analysis see Klingner, F., Hermes lxvi (1931), 159–89.Google Scholar

page 83 note 2 Lovejoy, and Boas, , op. cit., pp. 10–11.Google Scholar

page 83 note 3 469, 488; Klinger, , op. cit., pp. 175–6.Google Scholar

page 83 note 4 His political vision is made explicit at Aen. 6. 791–4: Augustus Caesar, diui genus, aurea condet saecula qui rursus Latio regnata per arua Saturno quondam.Google Scholar

page 83 note 5 G. 2. 473–4, 537; Ar. 132–4.Google Scholar

page 83 note 6 The idea that country people were the last descendants of Saturnus is not new, for it occurs in Varro, (R.R. 3. I. 15Google Scholar); in Horace's idealization in Epode 2 of the life of those who live in the country ‘ut prisca gens mortalium’ the Sabina uxor is taken as typical (41).

page 83 note 7 2. 4. 24.

page 84 note 1 Virgil adapted 1. 585 from this passage at G. I. 341Google Scholar, as the commentators note: ![]()

![]() —turn pingues agni et turn mollissima uina.

—turn pingues agni et turn mollissima uina.

- 4

- Cited by