Article contents

The First Greek Sophists

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1950

References

page 8 note 1 History of Greece, ch. Ixvii.

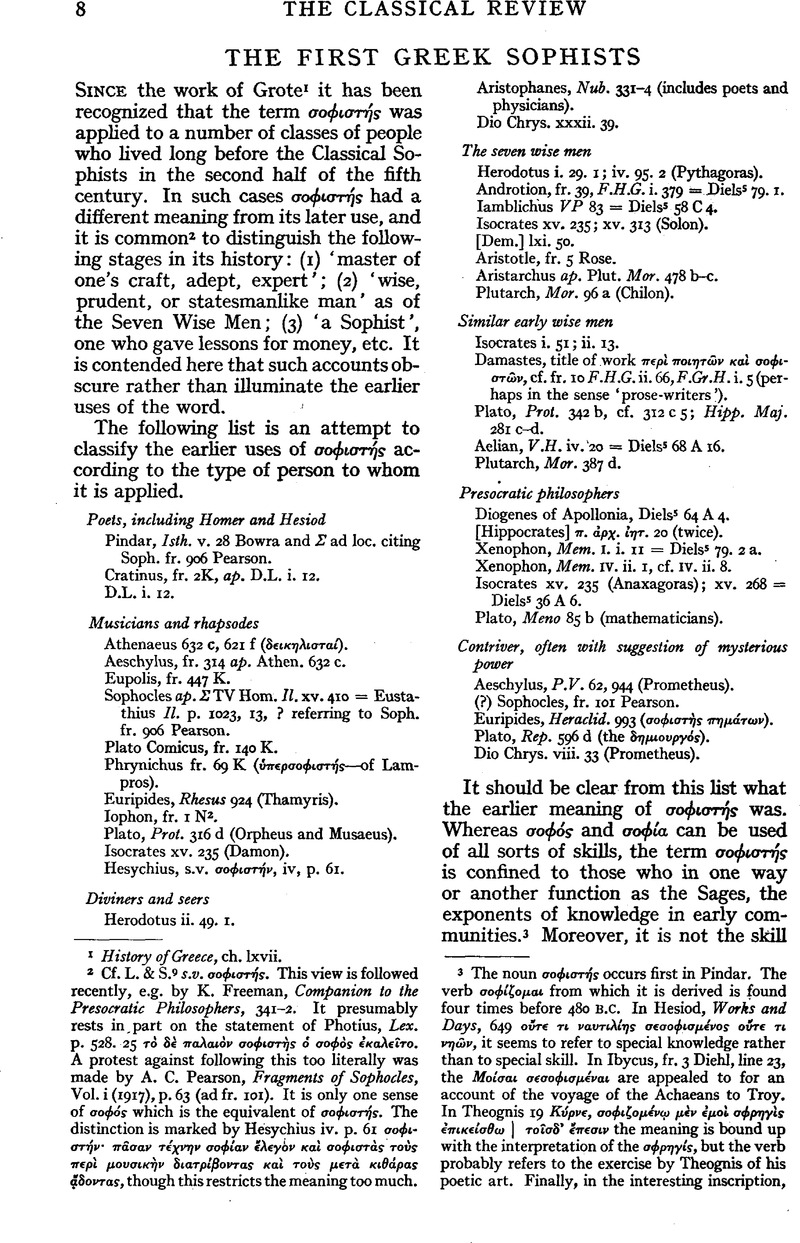

page 8 note 2 Cf. L. & S.9s.v.σοΦιστής. This view is followed recently, e.g. by K. Freeman, Companion to the Presocratic Philosophers, 341–2. It presumably rests in, part on the statement of Photius, Lex. p. 528. 25 τ⋯ δ⋯ παλαι⋯ν σοφιστ⋯ς ⋯ σοφ⋯ς ⋯καλεῖτο. A protest against following this too literally was made by Pearson, A. C., Fragments of Sophocles, Vol. i (1917), p. 63 (ad fr. 101)Google Scholar. It is only one sense of σοΦός which is the equivalent of σοΦιστής. The distinction is marked by Hesychius iv. p. 61 σοφιστ⋯ν π⋯σαν τ⋯χνην σοφ⋯αν ἔλεγον κα⋯ σοφιστ⋯ς τοὺς περ⋯ μουσικ⋯ν διατρἰβοντας κα⋯ τοὺς μετ⋯ κιθ⋯ρας ᾅδοντας, though this restricts the meaning too much.

page 8 note 3 The noun σοΦιστής occurs first in Pindar. The verb σοΦίςομαι from which it is derived is found four times before 480 B.C. In Hesiod, Works and Days, 649 οὔτε τι ναυτιλ⋯ης σεσοφισμ⋯νος οὔτε τι νη⋯ν, it seems to refer to special knowledge rather than to special skill. In Ibycus, fr. 3 Diehl, line 23, the Μο⋯σαι σεσοφισμ⋯ναι are appealed to for an account of the voyage of the Achaeans to Troy. In Theognis 19 Κ⋯ρνε, σοφιζομ⋯νῳ μ⋯ν ⋯μο⋯ σφρηγ⋯ς ⋯πικεἰσθω | τοῖσδ᾽ ἔπεσιν the meaning is bound up with the interpretation of the σΦρηγίς, but the verb probably refers to the exercise by Theognis of his poetic art. Finally, in the interesting inscription, I.G. i2.678 [$ε¯$σθλ⋯ν] τοῖσι σοφο$ι¯$σι σο[φ]⋯ζεσθ[αι κ]ατ[⋯τ⋯χνην | ὃς γ⋯ρ] ἕχ$ε¯$ι $τ¯$⋯χν$η¯$ν, λῴον᾽ ἔχ[ει β⋯οτον] the verb may well refer to the art of the poet or sage.(This meaning was rejected by von Gaertringen, H., Hermes, liv (1919), 329 f.Google Scholar, on the ground that there were no sophists before the Persian wars. Similarly Friedländer, P., Epigrammata, p. 124.)Google Scholar

page 9 note 1 Cf. δϵινός in Eur. Rhesus 924 (restored), Dio Chrys. xxxii. 39, Plutarch, Sertorius 10, ? Soph, fr. 906 Pearson; θανμασός in Plato, Rep. 596 d; νωθής in Aeschylus, P.V. 62. δϵινός is frequently applied to the later sense of the word (professional teacher).

page 9 note 2 That the etymology may have been an early one is suggested by Solon, fr. 1, line 51–2 ἄλλος Ὀλυμπι⋯δων Μουσ⋯ων παρ⋯ δ⋯ρα διδαχθε⋯ς, | ἱμερτ⋯ς σοφ⋯ς μ⋯τρον ⋯πιστ⋯μενος. If this passage has σοΦιστής in mind it would show that the use of the noun in the sense of ‘poet’ goes back to the beginning of the sixth century.

page 9 note 3 The striking similarities of Plut. Per. 4. 1–2 to the present passage in the Protagoras are accompanied by such equally striking differences that it is hard to suppose that Plutarch is drawing on Plato. This raises the possibility that both Plato and Plutarch are drawing on a third common source from the fifth century. Cf. O. Gigon in Phyllbolia für Peter von der Mühll (1946), pp.113–16.

4 This passage, included in Ritter and Preller(no. 223), is unaccountably omitted in Diels5.

page 9 note 5 So Perrin, B., in his commentary on Plutarch, Themistocles and Aristides (1901)Google Scholar.

page 9 note 6 So Bauer, A. ad Plut. Them. 2. 4 (Plutarchs Themistokles für Quellenkritische Uebungen commentiert, Leipzig, 1884), and Siefert-Blass-Kaiser, Plutarch: Themistokles und Perikles, Schulausgabe, adloc.Google Scholar

page 9 note 7 Surveyed by Nestle, W. in Philologus, lxx (1911), 258 ffGoogle Scholar.

page 10 note 1 That the term ‘sophist’ may be contemporary with Solon is further suggested by Solon, fr. 1, line 52, see above p. 9, n. 2. Prodicus ap. Plat., Euthyd. 305 c–d = Diels5 84 B 6, seems to refer to similar such early sophists.

page 10 note 2 Lattimore, R., ‘The Wise Adviser in Hero Herodotus’, in Class. Phil., xxxiv (1939), 24–35.Google Scholar

page 10 note 3 For a discussion of how the work of the ‘presophistic’ sophists was carried on by the Classical Sophists, see Morrison, J. S., ‘An Introductory Chapter in the History of Greek Education’, in Durham University Journal, xli (1949), 55–63.Google Scholar

- 6

- Cited by