No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

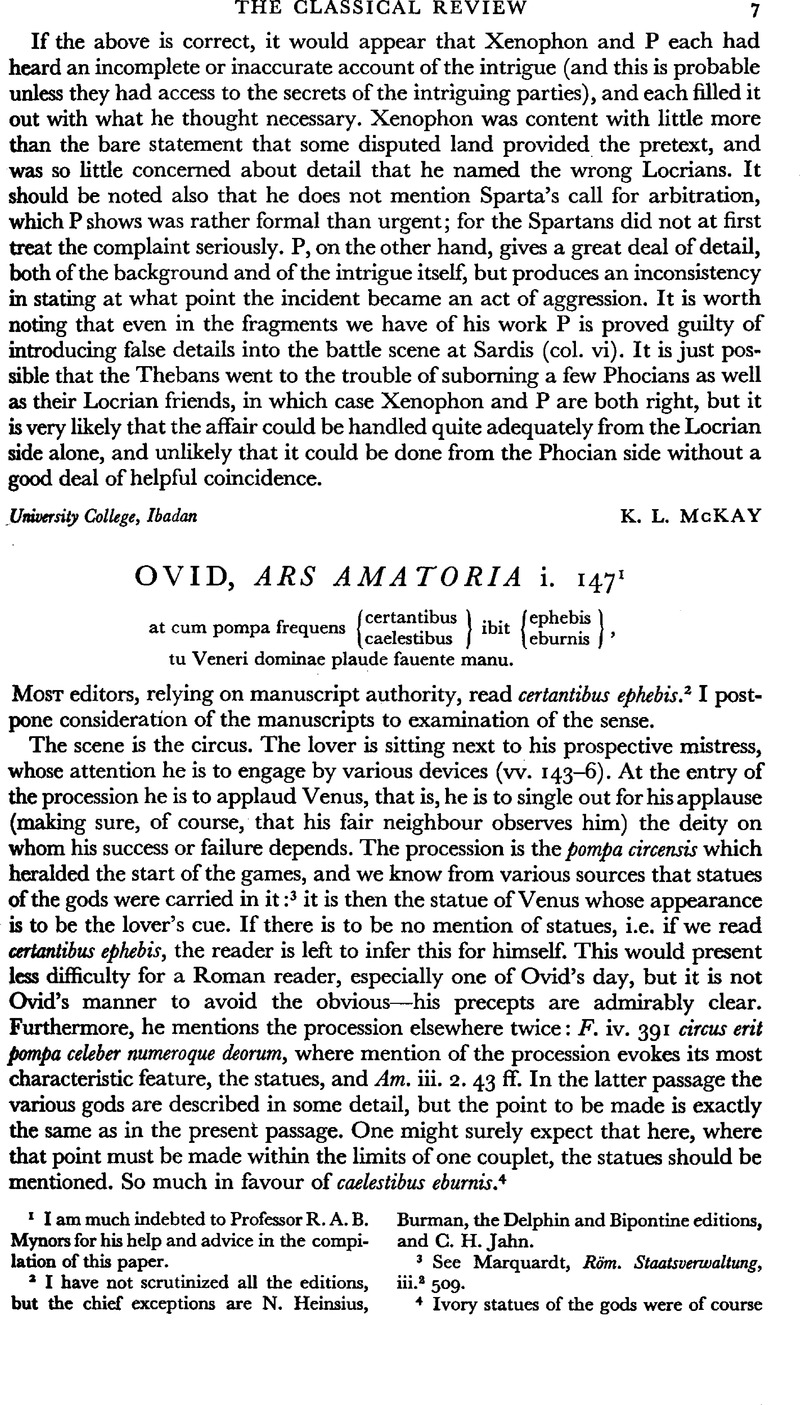

Ovid, Ars Amatoria i. 1471

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1953

References

page 7 note 2 I have not scrutinized all the editions, but the chief exceptions are N. Heinsius, Burman, the Delphin and Bipontine editions, and C. H. Jahn.

page 7 note 3 See Marquardt, Röm. Staatsverwaltung, iii.2 509.

page 7 note 4 Ivory statues of the gods were of course fairly common in temples, and the statue of Julius Caesar which was carried in the pompa circensis in his lifetime was of ivory (Dio xliii. 45. 2), as were those carried in honour of Germanicus and Britannicus after their deaths (Tac. A. ii. 83. 2; Suet. Tit. 2). At Am. iii. 2. 44 the procession is called aurea, but I take this to refer to its general appearance = ‘brilliant, glittering’. Aureus in Ovid often seems to have a double meaning, as at A.A. i. 214 quattuor in niueis aureus ibis equis, where aureus refers both to the triumphal garb of the young general (see e.g. Ehlers, R.E. 2. R. vii. A. 1. 505. 19 f. s.v. triumphus) and to his beauty (cf. aureus Amor, aurea Venus with Greek χρυσ⋯η,Ἀφροδ⋯τη and see Thes. ii. 1491. 61 if.). In fact the tensae used in the procession may have been of ivory: cf. Titinius ap. Fest. p. 554 Lindsay. The statues themselves were sometimes gold: Hist. Aug. Marc. Ant. 21.5.

page 8 note 1 1 See e.g. Marquardt, op.cit., pp.525f. and notes. Merula also in his note ad loc. under stood cert. eph. to refer to the Troy game; ‘certantibus ephebis uel pueris in ludo troiano pugnantibus uel digladiantibus inter se cybeles sacerdotibus: qui (ut Apuleius scribit) erant semiuiri effoeminati cinedi’, etc. This latter interpretation, absurd as it is, at any rate gives a possible sense for ephebis.

page 8 note 2 Cf. for (4) and (c) Suet. Aug. 43. 2 ‘Troiae lusum edidit frequentissime maiorum minorumque puerorum’ (cf. lul. 39. 2). I do not know where in common parlance one draws the line, especially in poetry, between a puer and a iuuenis, but clearly a minor puer is not an ephebus. I have not seen it suggested that the reference is to the nobilissimi iuuenes who performed at Caesar's games (Iul. 39. 2), but this would still be open to objections (b) and (c).

page 8 note 3 And post-classical writers tend to obstatues serve the distinction still. There is nothing to commend ephebus as a synonym for puer or iuuenis except its metrical convenience at the end of a hexameter.

page 9 note 1 I take the report of the Florentine manuscript from Marchesi's edition. The two Heinsiani are the Iureti liber and the Comelinianus. The former I have not been able to identify: the latter is Leiden Univ. Periz. Q. 16, of the 13th century, where caelestibus eburnis is a variant.

page 9 note 2 I imply no disrespect: it is the best manuscript, but it has been handled by editors with insufficient circumspection, as will be seen.

page 9 note 3 With occasional variants gaudentibus, plaudentibus, cantantibus.

page 9 note 4 There are a few others: Antwerp Mus. Plant. O.B. 5. 1 (formerly Lat. 68, anc. 43), 12th/13th century, the Moreti liber of Heinsius, has cael. eb. as a variant. Wolfenbüttel Bibl. Aug. 4260 (Gudianus 313), 13th/14th century, the Rottendorphianus of Heinsius, has certantibus eburnis in the text and ephebis added by a second hand. These may not be all. (Marchesi notes that Neapolitanus Nat. IV F. 13 has celestibus ephebis.) I have since discovered that Tours 879 (12th/13th century) has celestibus eburnis in its text and the fragment Bodl. MS. Rawl. Q,. d. 19 (S. C. 16044, 13th century) has certantibus ephebis tcelestibust plaudentibus and in the margin the note ‘imaginibus celestium ex ebore factis’. 9 5 S. Tafel, Die Überlieferungsgeschichte von Ovids Carmina Amatoria verfolgt bis zum 11. Jahrhundert, Tübingen, 1910.

page 9 note 6 The possibility that OS have a common intermediate ancestor does not commend itself: S is on the whole closer to R than to O (Tafel, p. 16). Only at one passage have OS a common error, at i. 218, where both omit que. Elsewhere the discrepancies between R1 and OS are due to simple error in R1

page 9 note 7 Merkel, praef. vi–vii; Tafel, p. 16; Marchesi, praef. ix; Bornecque, praef. viii.