No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

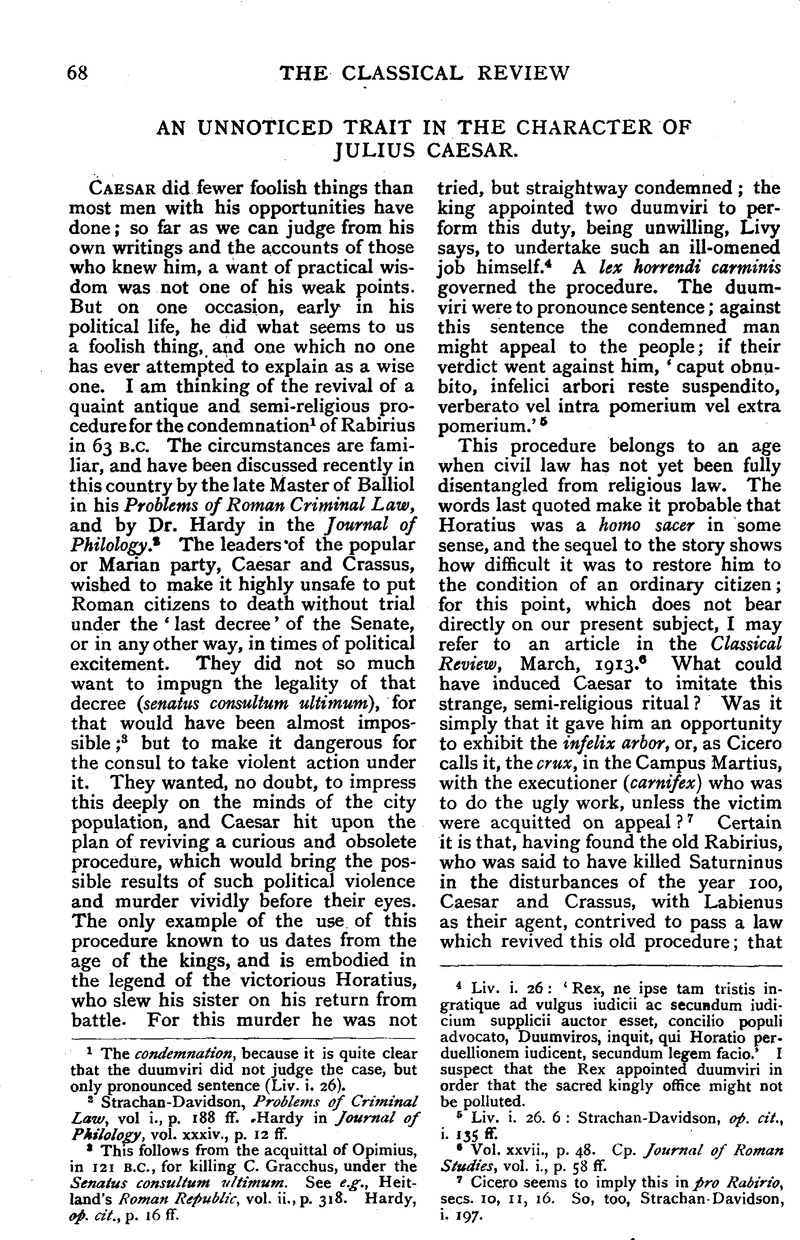

An Unnoticed Trait in the Character of Julius Caesar

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1916

References

page 68 note 1 The condemnation, because it is quite clear that the duumviri did not judge the case, but only pronounced sentence (Liv. i. 26).

page 68 note 2 Strachan-Davidson, , Problems of Criminal Law, vol i., p. 188 ffGoogle Scholar. Hardy, in Journal of Philology, vol. xxxiv., p. 12 ffGoogle Scholar.

page 68 note 3 This follows from the acquittal of Opimius, in 121 B.C., for killing C. Gracchus, under the Senatus consultum ultimum. See e.g., Heitland's, Roman Republic, vol. ii., p. 318Google Scholar. Hardy, op. cit., p. 16 ff.

page 68 note 4 Liv. i. 26: ‘Rex, ne ipse tam tristis ingratique ad vulgus iudicii ac secundum iudicium supplicii auctor esset, concilio populi advocato, Duumviros, inquit, qui Horatio perduellionem iudicent, secundum legem facio.’ I suspect that the Rex appointed duumviri in order that the sacred kingly office might not be polluted.

page 68 note 5 Liv. i. 26. 6 : Strachan-Davidson, op. cit., i. 135 ff.

page 68 note 6 Vol. xxvii., p. 48. Cp. Journal of Roman Studies, vol. i., p. 58 ffGoogle Scholar.

page 68 note 7 Cicero seems to imply this in pro Rabirio, sees. 10, 11, 16. So, too, Strachan-Davidson, i. 197.

page 69 note 1 So Hardy, op. cit, p. 28. Strachan-Davidson thinks that Cicero interfered, either as consul or through the agency of a tribune.

page 69 note 2 ‘Cum mane ad comitia descenderet, praedixisse matri osculanti fertur, domum se nisi pontificem non reversurum’ (Suet.Jul. 13).

page 69 note 3 Religious Experience of the Roman People, p. 343. According to Velleius, ii. 43, Caesar had been made a pontifex during his absence in Asia as a young man, and hurried home to Italy to take up the office, which suggests that he was in earnest about these priesthoods.

page 69 note 4 Suet. Jul. i, ad init. Frazer, Adonis, etc., p. 409.

page 70 note 1 Suet. Jul. 6.

page 70 note 2 It is worth remembering that the Julii were charged with the care of the cult of Veiovis at Bdvillae. C. I. L. i. 807, and Wissowa, Rel. und Kult der Römer, ed. 2, p. 237.

page 70 note 3 Plutarch, Caesar, ch. 9, is very explicit about this. Whence did he get his information about Caesar's private life?

page 70 note 4 D. C. xliii. 24.

page 70 note 5 Cp. de Bell., Afr., 98, and Cic. ad Fam. vi. 14; which letter is dated A.D. 5 Kal. intercalares priores (two intercalary months were that year inserted between November and December).

page 70 note 6 Roman Ideas of Deity, p. 118.

page 71 note 1 Suet. Jul. 81.

page 71 note 2 Ancient Lives of Virgil, p. 40.

page 71 note 3 Plutarch, Caesar, 32.

page 71 note 4 Roman Festivals, p. 330. Caesar seems to have been fond of horses, and rode one of which Suetonius tells strange things (Jul. 61), and which would allow no one to mount him but Caesar. He afterwards placed a statue of this horse in front of his temple of Venus Genetrix.

page 71 note 5 De Bell. Gall. vi. 13–19.

page 71 note 6 Nat. Hist. xxviii. 21.

page 71 note 7 Suet. Jul. 59. Ne religione quidem ulla a quoquam incepto absterritus unquam vel retardatus est.