No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

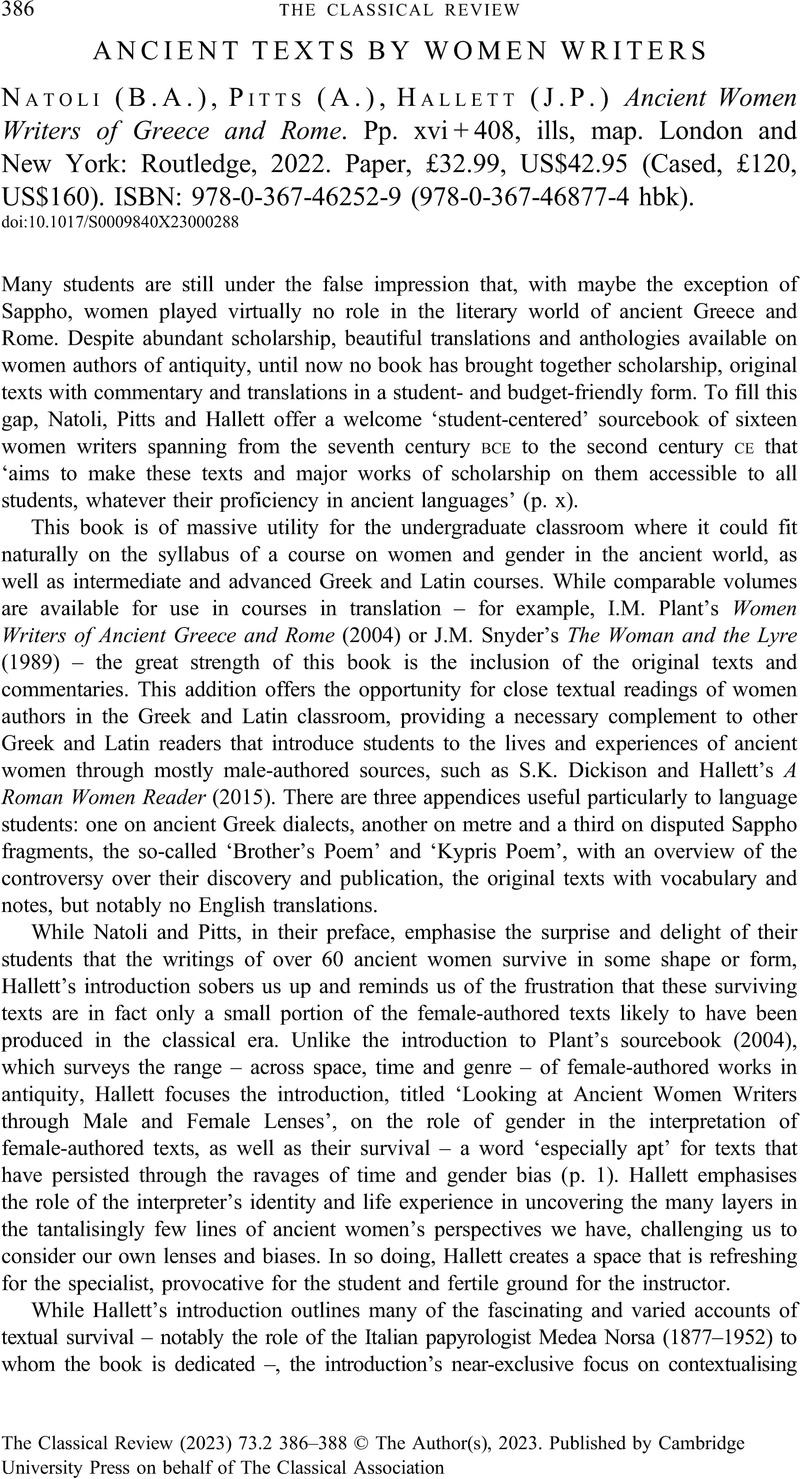

ANCIENT TEXTS BY WOMEN WRITERS - (B.A.) Natoli, (A.) Pitts, (J.P.) Hallett Ancient Women Writers of Greece and Rome. Pp. xvi + 408, ills, map. London and New York: Routledge, 2022. Paper, £32.99, US$42.95 (Cased, £120, US$160). ISBN: 978-0-367-46252-9 (978-0-367-46877-4 hbk).

Review products

(B.A.) Natoli, (A.) Pitts, (J.P.) Hallett Ancient Women Writers of Greece and Rome. Pp. xvi + 408, ills, map. London and New York: Routledge, 2022. Paper, £32.99, US$42.95 (Cased, £120, US$160). ISBN: 978-0-367-46252-9 (978-0-367-46877-4 hbk).

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association