No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

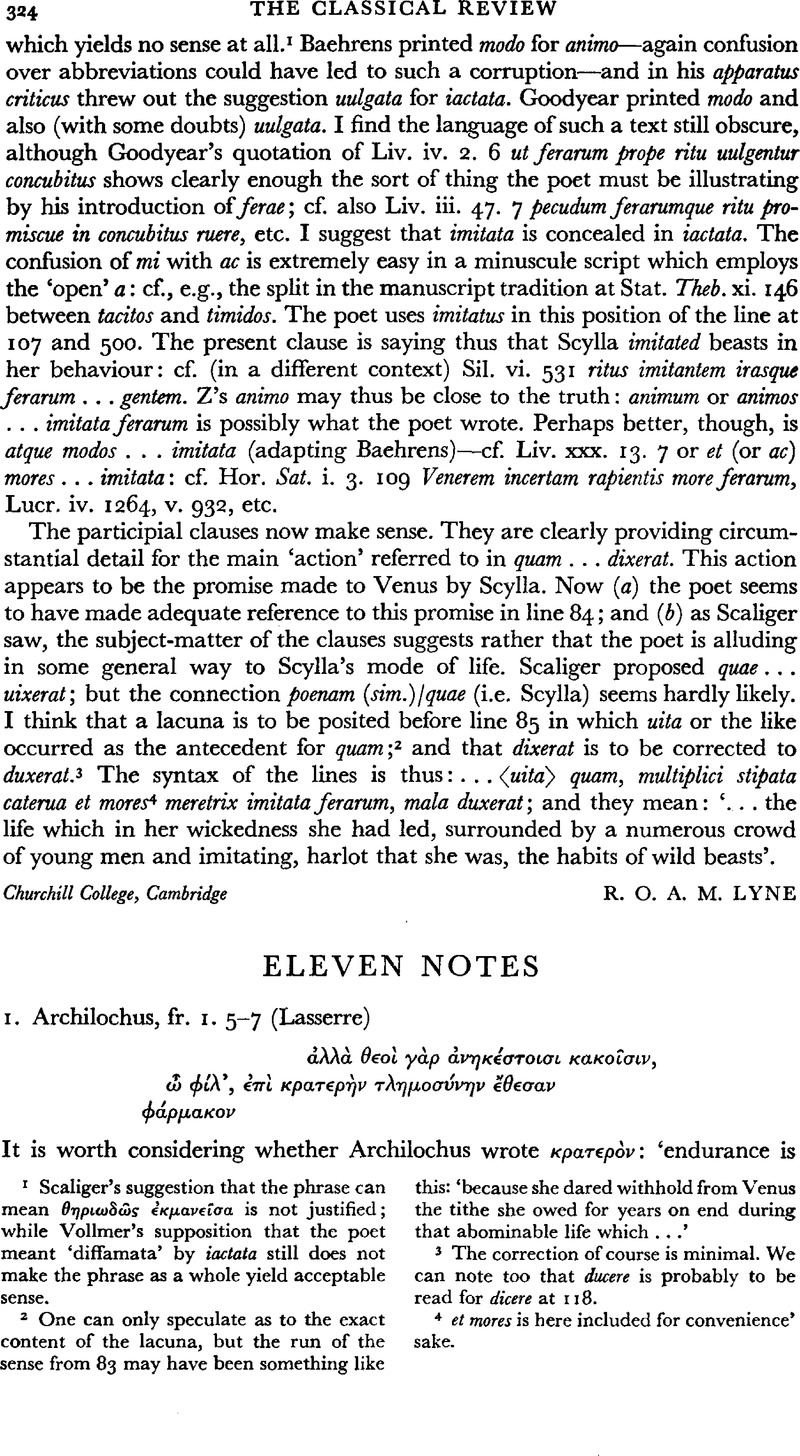

Eleven Notes

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1971

References

page 325 note 1 The rare word τλημοσ⋯νη is discussed by Heitsch, in Hermes xcii (1964), 257–264, but he has nothing to say about the appropriateness of κρατερ⋯ν.Google Scholar

page 325 note 2 Homer can be even bolder (Il. xvi. 104–5), and one hyperbaton in Solon is so bold as to be in bad taste (1. 43–5 Diehl).

page 325 note 3 His reference to the passage runs as follows:Ὀμηρικ⋯ν δ⋯ τι καἰ παρ⋯ Σοφοκλεῖ ⋯ν Φιλοκτ⋯τῃ τ⋯ “ οὔτε τι ῥ. Jebb is quite unfair to him when he says: ‘The last three words prove … that οὔτε τι ῥ⋯ξας in his citation of Sophocles was a mere slip for οὔτ' ἔρξας τιν': since, if his text of our verse had really contained τι, he could not have said σιωπ⋯ται τ⋯ ῥεχ⋯ν.' To pass over the unlikeliness of such an absurd slip, Eustathius’ point is that by ‘done nothing’ Sophocles means ‘done nothing nasty’, and ‘nasty’ σιωπ⋯ται

page 325 note 4 Maas, , Greek Metre, § 130,Google Scholar implies that ῥ always behaves as a double consonant in tragic lyrics, which is far from being true even of other words than ῥ⋯χειν (e.g. Eur. Hel. 1117 ἔδραμἔ ῥ⋯θια, Bacch. 128 τἔ Ῥ⋯ας 150 αἰθ⋯ρᾰ ῥ⋯πτων).

page 325 note 5 The best solution might then be <οὐδ⋯ν> οὔρξασ τιν' οὔτε νοσφ⋯σας. The difficulty of expressing the requisite sense in anything less than a full trimeter speaks strongly in favour of Jackson's supplement in 699, which has been accepted by Page, Proc. Comb. Phil. Soc. clxxxvi (1960), 52.

page 325 note 6 ‘Quae interposita sunt, ⋯γαπ⋯ν παιδαρ⋯ου κ⋯λλος—⋯π. ⋯ν⋯ς, ea quid signified istud τῷ παρ' ⋯ν⋯ δουλε⋯ων accuratius pleniusque declarant’ Wohlrab (1877), correctly, except that ὥσπερ οἰκ⋯της belongs to the explanation; but Wohlrab did not suspect interpolation.

page 328 note 1 Mr. James O'Sullivan points out that this reading is sound and Cobet's conjecture unnecessary. In fairness to Cobet it should be added that he knew no reading but ⋯ποχρ⋯σαι

page 328 note 2 Even if Scholte and Harrison were wrong, I hope my colleague John Griffith will forgive me, quae est eius indulgentia, when I say that they cannot be answered by an appeal to ‘Juvenal's habit of parenthesis’ (C.Q. lxiii [1969], 380). He writes: ‘There is … no need for the emendation ecquando in 87, once lines 85–6 are mentally or actually enclosed in parenthesis and et in 87 is given its idiomatic function of introducing an indignant question, which looks back to the ex quo clause.’ Once lines 85–6 are ‘mentally or actually enclosed in parenthesis’, the et in 87 is connecting a dependent and an independent clause.

He is also mistaken in thinking that Harrison's note has been ‘quietly forgotten’ except by Knoche: see Nisbet's review of Clausen's O.C.T. (cited in the next sentence above), which also contains a brief commendation of rubeta at 1. 70 and an attractive suggestion at 14. 269 (cf. Griffith 379, 386).

page 328 note 3 Tracking down Guyet, not to mention Plathner, F. Ritter, and Sebastiani, is no easy matter; and even though the names of scholars like Markland and Lachmann may be familiar, few people can have any idea how to find their observations on Juvenal. It is rather irksome, therefore, when editors who know the way to such places forbear to disclose it.

Among recent O.C.T.s practice has differed: Long in his Diogenes and Marshall in his Gellius, for instance, both help the reader, but Reynolds in Seneca and Mynors in Virgil do not. Is it too much to ask of the Clarendon Press that it should require all its editors to follow the better example ?

For the record, Guyet's contributions appear in the edition of M. de Marolles (Paris, 1671).