Article contents

Greek Verses from the Eighth Century B.C.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1956

References

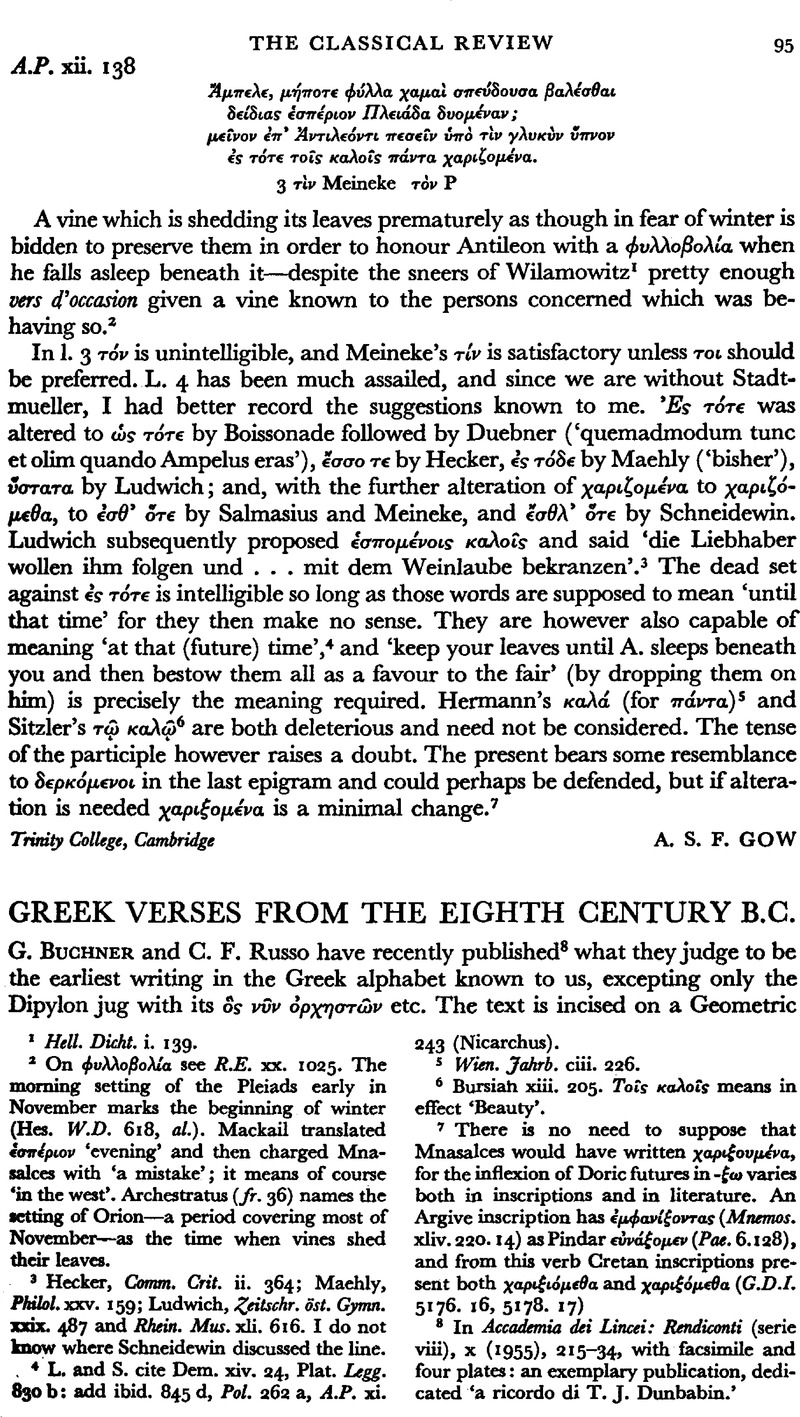

page 95 note 1 Hell. Dicht. i. 139.

page 95 note 2 On φυλλοβολία see R.E. xx. 1025. The morning setting of the Pleiads early in November marks the beginning of winter (Hes. W.D. 618, al.). Mackail translated ἑσπέριον ‘evening’ and then charged Mna-salces with ‘a mistake’; it means of course ‘in the west’. Archestratus (fr. 36) names the setting of Orion—a period covering most of November—as the time when vines shed their leaves.

page 95 note 3 Hecker, Comm. Crit. ii. 364; Maehly, Philol. xxv. 159; Ludwich, Zeitschr. öst. Gymn. xxix. 487 and Rhein. Mus. xli. 616. I do not know where Schneidewin discussed the line.

page 95 note 4 L. and S. cite Dem. xiv. 24, Plat. Legg. 830 b: add ibid. 845 d, Pol. 262 a, A.P. xi. 243 (Nicarchus).

page 95 note 5 Wien. Jahrb. ciii. 226.

page 95 note 6 Bursiah xiii. 205. Τοῖς καλοῦς means effect ‘Beauty’.

page 95 note 7 There is no need to suppose that Mnasalces would have written χαριξουμένα, for the inflexion of Doric futures in -ξω varies both in inscriptions and in literature. Argive inscription has ἐμφανίξοντας (Mnemos. xliv. 220.14) as Pindar εὐνάξομεν.(pae 6.128), and from this verb Cretan inscriptions present both χαριξιόμεθαand χαριξόμεθα (G.D.I. 5176. 16, 5178. 17)

page 95 note 8 In Accademia dei Lincei: Rendiconti (serie viii), x (1955), 215–34, with facsimile and four plates: an exemplary publication, dedicated ‘a ricordo di T. J. Dunbabin.’

page 96 note 1 The irregularity (if it is so to be judged) at the beginning of the line and the hiatus between ’ι and *epsi;υποτ- are characteristic of the genre. The possibility of Νέστωροσ is considered by the editors, p. 229 n. 2.

page 96 note 2 But the editors give good reason for thinking it unlikely that our poet had the Iliad's description in mind (p. 233). In general, the hexameters are strikingly unhomeric in vocabulary (πίησι, ποτήριον, καλλιστέφανος) and in formulas (αὐτίκα κεῦνον, ἵμερος αἱρήσει: contrast Il. iii. 446); see edd. pp. 230 f.

page 96 note 3 The editors say that the dividers ‘follow a precise rule’: substantives, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs are separated, pronouns and particles are not. I suggest that the evidence is insufficient for this generalizasition, and I can make no sense of a system in which two such coherent words as εὔποτον ποτήριον are divided whereas two such disparate elements as αὐτίκα κεῖνον are not. Moreover, on any rational system one would expect dividers between τοῦδε and πίησι. The writer originally left out the ς of ὄς and the ν of ἃν: there is obviously a possibility that he omitted their following dividers too.

- 2

- Cited by