No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

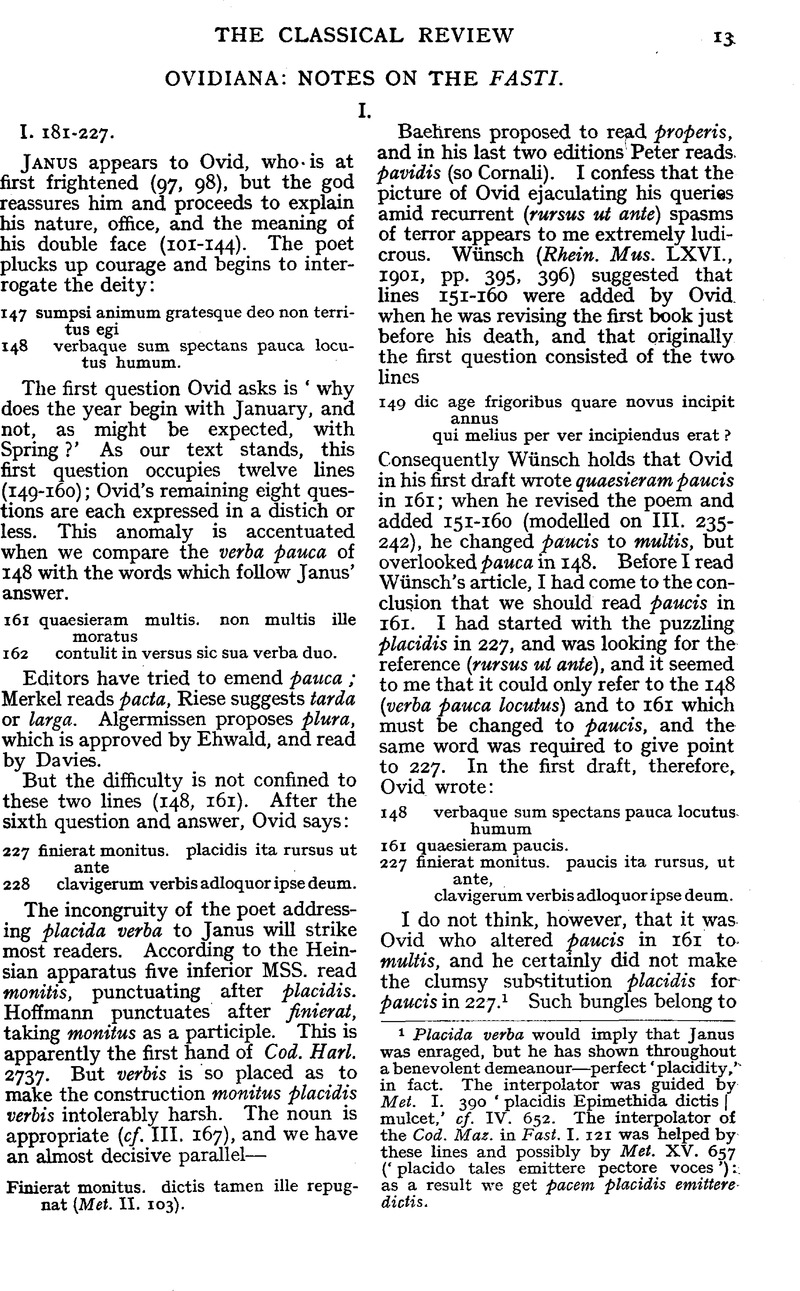

Ovidiana: Notes on the Fasti

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1918

References

page 13 note 1 Placida verba would imply that Janus was enraged, but he has shown throughout a benevolent demeanour—perfect ‘placidity,’ in fact. The interpolator was guided by Met. I. 390 ‘placidis Epimethida dictis | mulcet,’ cf. IV. 652. The interpolator of the Cod. Maz. in Fast. I. 121 was helped by these lines and possibly by Met. XV. 657 (‘placido tales emitterc pectore voces’):; as a result we get pacem placidis emittere dictis.

page 14 note 1 A recent examination of the cod. Mazarinianus inclines me to believe that it is a direct copy of a MS. of which a portion survives— the fragm. Ilfeldense, see Merkel, p. cclxxiii. The Zulichemianus may be a collation of the same MS., which Merkel assigns to the twelfth century.

page 14 note 2 dextro is found in Zmfss; ‘it is established beyond possibility of doubt by Becker, , R.A., p. 138Google Scholar (Peter, app., p. 28). It is approved by Heinsius, Ehwald, Vahlen, and many others.

page 14 note 3 On Ovid's debt to Livy, see Neapolis, Heinsius, and early editors; also Schenkl, K., Ztscht. f. öster. Gymn. XI. (1860), pp. 401 f.Google Scholar, Sofer, E., Livius als Quelle von Ovids Fasten, Wien, 1906.Google Scholar

page 14 note 4 See H. Winther, ‘de Fastis Verrii ab Ovidio adhibitis, Berol., 1885. Winther's view that Verrius is the only source of Ovid's information is, of course, quite untenable, as Ehwald (Jahresb., XLIII. p. 172) and Wissowa (Anal. Rom. Top., Munich, 1904, p. 271) show.

page 15 note 1 Of course, a fact is sometimes presented as a condition, e.g., Rem. 567, 568, ‘est tibi rare bono generosae fertilis uvae | vinea: ne nascens usta sit uva time.’ But in such cases the real condition, qualified by the expressed fact, is understood. In the Rem. it would be ‘si tu, cui est vinea, non vis amare.’ If we accept Vahlen's view of the passage in the Fasti, the context does not provide the general condition (‘si vis loca ominosa vitare’). The hypothetical proposition is sprung on us without any warning, and the abruptness is accentuated by the categorical form and the omission of the logical subject, for which we have to wait till we reach ‘quisquis es.’

page 15 note 2 Even Ehwald feels the difficulty; he proposed formerly to read ‘per hunt’ (Jakresb. XLIIL, p. 171). Is not proxima, moreover, a curious way of describing a road passing through an arch?

page 15 note 3 Dextra est is the reading of V and the majority of the MSS. It is in such early editions as I have seen, and is retained by Merkel, Riese, Paley, Hallam; see Winther, op. cit. pp. 50 f. Jordan (Top. I. 1, 239, footnote) suggests that dextro iano in Livy, I.c., means ‘with the temple of Janus on their right’; cf. Hermes, IV., p. 234.

page 15 note 4 See Havet, Man. de C. V., p. 180.

page 16 note 1 The distich perhaps was

‘arx mea collis erat, quem cultum nomine nostrum nuncupat haec aetas Ianiculumque vocat.’

Quem vulgus codd. The hill was in olden days the arx Iani, over against the arx Saturni (cf. Aen. VIII. 357): in Ovid's day it was called the collis nomine Iani cultus, i.e. the Iani-culum. vulgus is a gloss on haec aetas. If Heinsius is right in his view that Carmens was an adjective = Carmentalis (see his note on IV. 875), we could read Carmenti porta duxit v. p. I. But I cannot find any support for Carmens.

page 16 note 2 Mommsen suggested that the porta Ianualis (=Ianus Geminus of the forum Romanum) of the original legend was confounded with the dexter ianus of the porta Carmentalis, see Jordan, I.c.

page 16 note 3 It is to this temple that Ovid refers in I. 223–226. It was the only real Temple of Janus in Rome. It had originally been vowed by Duillius at Mylae: Augustus had undertaken its restoration, and the new foundation was dedicated by Tiberius in 17 A.D. See Wissowa, , Rel. u. Kult., p. 106Google Scholar; Jordan, , Top. I. 1, p. 347Google Scholar; Jordan-Huelsen, I. 3, p. 508; Richter, , Top., p. 194.Google Scholar

page 16 note 4 For Ovid's echoes of Propertius, see Zingerle, , Ovidius u. sein Verhāltniss zu den Vorgängern u. gleichzeitigen röm. Dichtern, Pt. I., Innsbruck, 1869Google Scholar. Of course Ovid derived much profit from Propertius, especially from the Roman elegies; see Schanz, p. 147, Peter, Introd., p. 14.

I have confined myself in the foregoing note to the discussion of line 201. I must, however, add that I share the views of those (against whom Vahlen fulminated) who regard lines 203, 204 as spurious. The distich is omitted by R and the first hand of V. The interpolator versified what were, perhaps, in his MS. only explanatory glosses.

page 16 note 5 By the Cod. (or Codd.) Nauger. Heinsius meant just the text of the third Aldine edition (1533). Heinsius seems to have forgotten that the editor was Fasitelius, not Navagero. Merkel (praef. p. ccxci) is misleading). In two cases (here and V. 701) Heinsras' reference to Naugerius is appropriate, for the reading is taken from the list of ‘variae lectiones’ given by Navagero in the second volume of the 1516 Aldine, a list which Fasitelius copied incorrectly in the third volume of the 1533 edition, though he paid little or no attention to these readings in choosing his text. ‘Petav.’ is a slip for ‘Petavianus alter,’ as Heinsius' MSS. notes (in Merkel) show.

page 17 note 1 P. 23, de Ovidi Fastis recensendis: diss. inaug. Suerini, 1887.

page 17 note 2 Heinsius' alternative suggestion—nunc caelum sidera munus habent—is neat though improbable. The crude cerni sidera munus habent (‘have as reward the right to be seen in the form of stars’) is matched only by the equally doubtful distich

‘inde : diem, quae prima, meas celebrare Kalendas Oebaliae matres non leve munus habent’ (III. 229, 230),

Which Heinsius, Burman, Merkel (Reim.), and others read. I hope to discuss the whole passage later. At present (cf. VI. 101) I am inclined to think that Ovid wrote something like—

‘inde dies data prima deae: celebrate Kalendas Oebaliae matres, non leve nomen habent.’

nomen R ; for confusion of meas and deae cf. II. 782; celebrare—celebrate is a very common blunder, cf. IV. 865, 759, II. 533, 557. Data was perhaps abbreviated in the archetype. The root of the mischief was the charge of deae to meae—meas ; cf. II. 782 where R has meusque for deusque. I overlooked the reading of the 1629 Elzevir (Dan. Heins.) ‘pro quo nunc, cernis, sidera numen habent.’ numen is found, according to the Heinsian apparatus (Merkel) only in one second class MS. The objections to this reading was obvious. Ovid uses numen habere to indicate that a person or place is ‘possessed’ by a deity, not to describe an apotheosis or ‘apasterosis.’

page 18 note 1 Some inferior MSS. have quod nos ut cernis habemus or manibus quod cernis habere (cf. Fast. III. 116); the former is the reading of the 1533 Aldine, the latter of the 1502 Aldine and the editions of Gryphius, Bersmann, and others. Heinsius thought of manibus quod cernis haberi, but finally agrees with Gronovius (0bb. IV. c. 18) in accepting quod cernis habemus. He cites Aen. VI. 760 ‘ille, vides, pura iuvenis qui nititur hasta | proxima sorte tenet lucis loca,’ where the object of vides is easily supplied by the preceding ille, almost like ille quem vides; the speaker here also as in Met. VII. 756 is a definite person (Aeneas).

page 18 note 2 Cf. Ex Pont. III. 7, 8 ‘ne toties contra quam rapit amnis earn,’ and A.A. II. 182: and perhaps Fast. V. 348 ‘ilia cothurnatas inter habenda deas’: Am. I. 11, 2 ‘docta neque ancillas inter habenda, Nape.’ Nor would we expect lines like ‘iustaque de viduo-paene querela toro’ (Trist. V. 5, 48).

page 18 note 3 Prof. Housman gives a useful list of similar transpositions, Manilius, Bk. I, Introduction; see especially pp. lviii, lix.

page 18 note 4 Query poeta?

page 19 note 1 From line 721 ardea votis would perhaps be better (cf. IV. 895).

page 19 note 2 There is, however, a difference between restare and resistere: the former connotes rather passive than active resistance.

page 19 note 3 Otherwise one might suggest certas for restas

page 19 note 4 Captis or caesis (cf. 709) may have been, the missing word, but victa—victis is more Ovidian.