No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

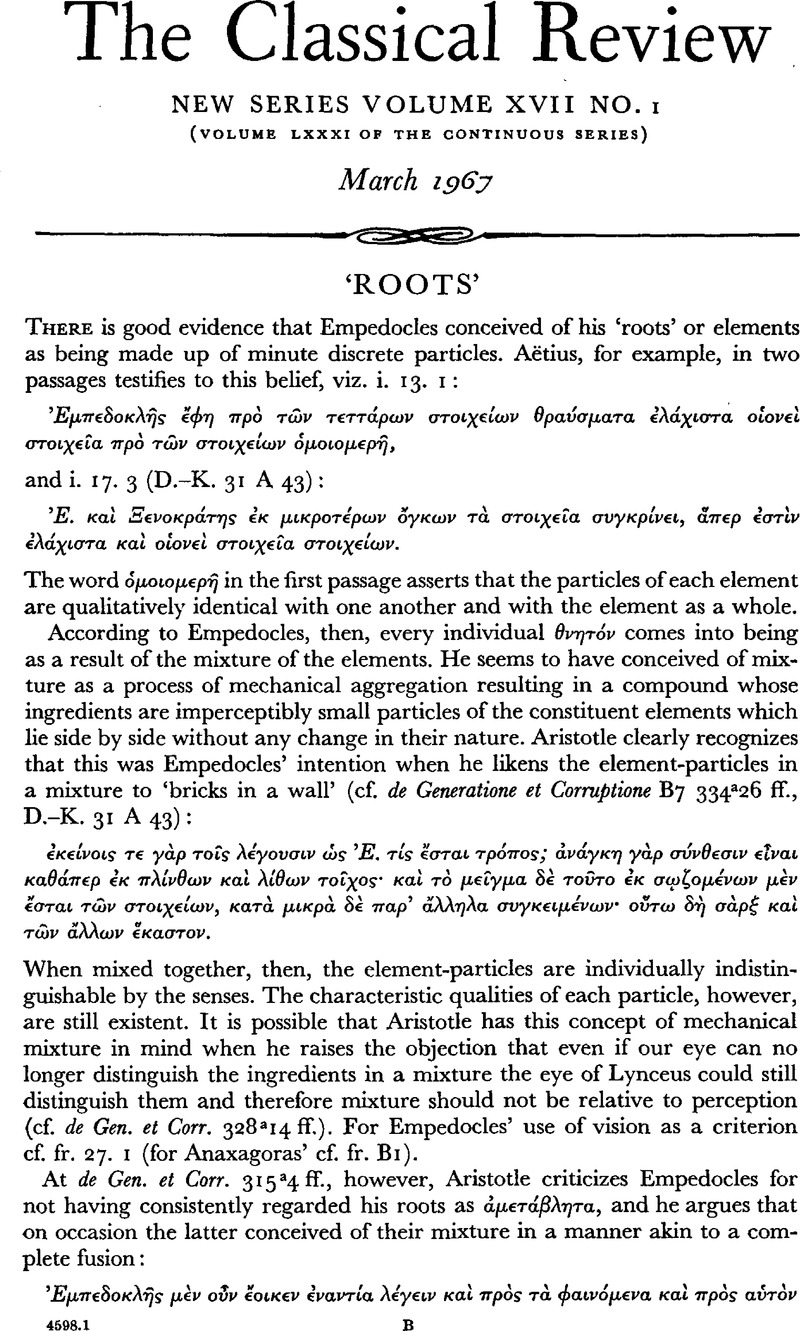

‘Roots’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1967

References

page 2 note 1 Cf. Aristotle's Criticism of Presocratic Philosophy (Baltimore, 1935), p. 121Google Scholar (cf., too, p. 96, n. 405; p. 36, n. 15, and pp. 50–51).

page 3 note 1 The begining of fr. 26 seems at first sight to support this view:

⋯ν δ⋯ μ⋯ρει κρατ⋯ουσι περιπλομ⋯νοιο κ⋯κλοιο, κα⋯ φθ⋯νει εἰς ἅλληλα κα⋯ αὔΞεται ⋯ν μ⋯ρει αἴσης.

Simplicius believes (in Phys. 160. 14 Diels) that Empedocles in these lines is asserting the mutual transformation of the elements, and modern scholars have frequently implied this in their translations. Verdenius, W. J., however, (‘Notes on the Presocratics’, Mnemosyne, iv. i (1948), pp. 12 ffGoogle Scholar. cited by Guthrie, , History of Greek Philosophy, ii, p. 146Google Scholar) has pointed out that such translation involves the mistranslation of φθ⋯νει and αὔβεται. These verbs do not mean ‘perish’ or ‘decline’ and ‘come into being’; they mean ‘grow smaller’ and ‘grow larger’. The implication of these verses is that, although the sum total of each element as well as its characteristics is constant, at any particular part of the cosmos the elements grow as particles of the same element come together (cf. 37) and diminish as they are separated from their own kind and mingle with the other elements.

page 3 note 2 On the Interpretation of Empedocles (Diss. Chicago), 1908, p. 21Google Scholar (cited by Guthrie, ii, p. 127, n. 1).

page 4 note 1 He refers to his elements indiscriminately by a variety of names. Fire, for example, in addition to its mythological representation is referred to as ‘Sun’ (both ἤλιος and ἠλ⋯κτωρ ‘flame’ (φλ⋯ξ), water by ‘rain’ (⋯μβρος) and ‘sea’ (both θ⋯λσσα and π⋯ντος), air as αἰθ⋯ρ, οὐραν⋯ς and πνε⋯μα, and earth as γαῖα, χθών and αἦα.

page 4 note 2 The received text of Clement, Strom. v. 48 actually mentions the sun but the reading is clearly corrupt. Diels–Kranz, adopting the suggestion of H. Weil (who cites B. 23. 10) ⋯ξ ὧν δ⋯λ' ⋯γ⋯νοντο for manuscript ⋯ξ ὧν δ⋯ ⋯γ⋯νοντο read:

εİ δ᾽ ⋯γε τοι λρ⋯θ᾽: ἥλιον ⋯ρχ⋯ν, ⋯Ξ ὧν δ⋯λ᾽ ⋯γ⋯νοντο τ⋯ ν⋯ν ⋯σορ⋯μεν ἃπαντα.

The text as it now stands suggests that the formation of the sun is under discussion. But C. H. Kahn, developing the suggestion of Diels for the first verse and following Friedländer in keeping the manuscript reading of the second, reads:

εἰ δ᾽ ἄγε τοι λ⋯Ξω τ⋯ τε πρ⋯τα κα⋯ ἤλικα ⋯ρχ⋯ν ⋯Ξ ὧν δ⋯ ⋯γ⋯νοντο τ⋯ ν⋯ν ⋯σορ⋯μεν ἅπαντα

(Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology (New York, 1960), p. 125, n. 1)Google Scholar, which certainly makes good sense.

page 4 note 3 For the basic idea they are probably both indebted to Anaximander.