Introduction

The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia decreased significantly after oral formulations of second-generation antipsychotics were introduced; however, the use of LAIs has increased slowly in recent years since the introduction of second-generation LAI antipsychotics.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1, Reference Correll, Citrome and Haddad2 Earlier data estimated that LAI antipsychotics were prescribed to between one-quarter and one-third of patients with schizophrenia in the United States, Australia, and EuropeReference Barnes, Shingleton-Smith and Paton3, Reference Patel, Taylor and David4; more recent data (2016) from the United States indicate that 11% of patients are prescribed LAI antipsychotics (data on file, Janssen).

LAI antipsychotics offer advantages over oral formulations,Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 because they provide assured adherence for the duration of the injection interval and beyond; this is particularly important for patients who have a history of poor adherence, lack of insight into their illness, or cognitive deficits that interfere with scheduled medication intake.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 Because patients receiving LAI antipsychotics do not have to remember to take medication daily, there are fewer opportunities for missed doses.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 With LAI antipsychotics, health-care providers (HCPs) are assured of continuous antipsychotic coverage during the dosing interval. In cases of patients failing to take their medication, there is a longer window for intervention, as the decrease of blood concentrations of antipsychotics is much more gradual after discontinuation of LAI antipsychotics than after discontinuation of oral antipsychotics (OAPs).Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1, Reference Weiden, Kim and Bermak5, Reference Samtani, Sheehan and Fu6 Patients also benefit from consistent bioavailability and potentially fewer peak concentration–related adverse events (AEs) observed with OAPs.Reference Bosanac and Castle7 Furthermore, clinicians are immediately aware when medication nonadherence begins (i.e., patients do not return for their scheduled injections).Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 Importantly, there is evidence that LAI antipsychotics reduce the incidence of relapse compared with oral formulations.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1, Reference Correll, Citrome and Haddad2, Reference Bosanac and Castle7 This in turn can decrease the frequency and duration of hospital stays associated with relapse, thereby reducing the overall burden on the patient and their caregivers, and on the health-care system.Reference Correll, Citrome and Haddad2, Reference Kane, Kishimoto and Correll8, Reference Kishimoto, Nitta and Borenstein9

Given that there are several first-generation LAI antipsychotics still on the market as well as an influx of newly available second-generation LAI antipsychotics (Table 1), it can be challenging to delineate which LAI antipsychotic is most appropriate for a particular patient. However, there are several practical considerations that should be considered when selecting a specific LAI. Because each LAI has unique attributes, selection should be tailored to match the unique needs of the individual. First, the HCP should consider the reason for using an LAI antipsychotic (e.g., patient preference, nonadherence, court order). The patient and the HCP should then discuss factors important to the patient, such as the expected or already experienced efficacy and AE pattern of the oral formulation of the same antipsychotic, the frequency of administration, whether an oral supplement is required upon initiation, and the financial cost or coverage of the treatment.Reference Citrome10 One potential disadvantage of LAI antipsychotics is the potential for delayed resolution of a distressing or severe side effect.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 HCP-specific practical considerations might include how each LAI is supplied, such as in prefilled syringes or in a form that requires reconstitution, and specific storage requirements (e.g., whether refrigeration is necessary). Limited or incomplete information on first-generation LAIs, such as the lack of drug-metabolism or drug-interaction data (these drugs were approved before the implementation of such US Food and Drug Administration requirements), may either preclude them as a viable choice for HCPs or make them difficult to use. Patient-specific practical considerations include access to care, needle size, or injection site location.Reference Citrome10 Thorough consideration of patient- and HCP-specific preferences will help guide selection of the appropriate LAI antipsychotic and potentially improve adherence and effectiveness among patients.

Table 1 Overview of long-acting injectable antipsychoticsReference Correll, Citrome and Haddad2, Reference Hiemke, Bergemann and Clement15, 20, 22–24, Reference Turncliff, Hard and Du36–46

Dash (—) = not applicable; LAI = long-acting injectable; PP1M = paliperidone palmitate once monthly; PP3M = paliperidone palmitate once every 3 months.

a For products available in the United States, doses are based on U.S. approval; doses in parentheses represent milligram-equivalent doses.

b Steady-state data refer to an ideal, average patient who is a “normal” metabolizer. These therapeutics may have a longer half-life in patients who are poor metabolizers (based on genetics or concomitant use of metabolic enzyme inhibitors) or a shorter half-life in those who are rapid metabolizers (based on genetics or concomitant use of metabolic enzyme inducers).

c Data on therapeutic reference plasma concentrations are preliminary.

d Time to peak values were derived from patients who received oral supplementation before LAI administration.

e Most PK data originate from studies by the pharmaceutical industry; studies conducted by academic investigators are limited.

Despite the many advantages that LAI antipsychotics offer over oral formulations,Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1 patients may experience psychotic breakthrough symptoms or symptomatic worsening during treatment, such as psychosis-related social withdrawal, anxiety, or depression; parkinsonian side effect–related secondary negative symptoms; or akathisia manifesting as agitation. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of data regarding management strategies in response to patients experiencing breakthrough symptoms, with only three articles identified during a recent literature search.Reference Llorca, Abbar and Courtet11–Reference Keith, Kane and Turner13 There are currently no algorithms, treatment guidelines, or clinical pathways to guide the management of LAI antipsychotic–treated patients who have breakthrough symptoms or who become acutely ill. Moreover, the only available guidelines for the therapeutic targets of LAI antipsychotics, produced by Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie (AGNP), are based on data from oral compounds.Reference Baldelli, Clementi and Cattaneo14, Reference Hiemke, Bergemann and Clement15 Therefore, HCPs must currently rely on their own clinical judgment to manage patients with breakthrough symptoms or symptomatic worsening. Herein, we provide practical solutions based on a framework of clinical, pharmacokinetic (PK), and dosing considerations to help HCPs make well-informed decisions regarding management strategies for patients presenting with breakthrough psychotic symptoms or symptomatic worsening while being treated with LAI antipsychotics.

General Factors That Contribute to Breakthrough Psychosis and/or Symptom Worsening

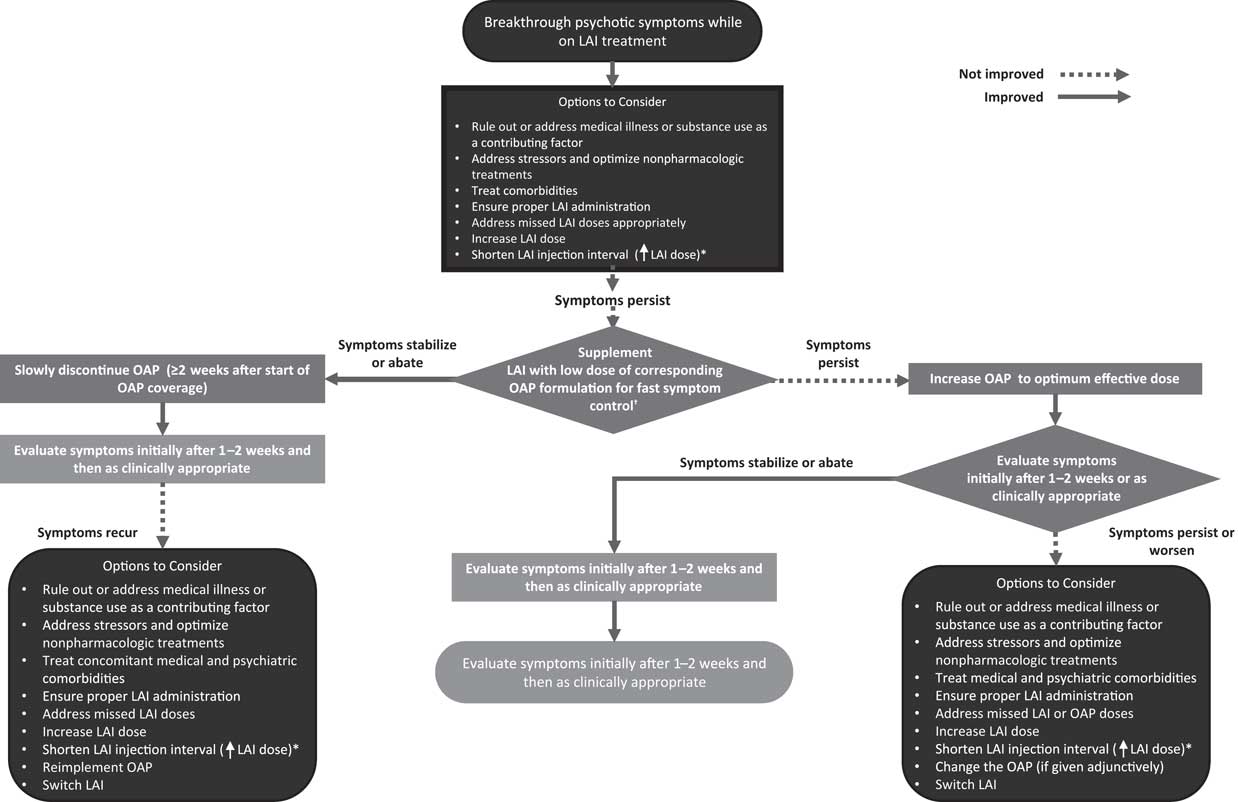

Breakthrough psychosis and/or symptom worsening may occur for a variety of reasons, including psychotic relapse, concurrent medical illness, substance abuse or misuse, other psychiatric comorbidity, psychosocial stressors, suboptimal drug administration, incorrect dosage, ineffective medication, use of other drugs leading to pharmacodynamic (PD) or PK interactions, poor adherence, and AEs leading to refusal or discontinuation of treatment.Reference Brissos, Veguilla, Taylor and Balanza-Martinez1, Reference Correll, Citrome and Haddad2, Reference Porcelli, Bianchini and De16 Low plasma therapeutic levels may also contribute to breakthrough psychosis. Therapeutic plasma reference ranges are now available in the new AGNP guidelines,Reference Hiemke, Bergemann and Clement15 and while these are preliminary, together with therapeutic dose monitoring they may be of some use toward medication and dosing decision making, as exemplified in Table 2.Reference Saklad17 Idiopathic symptomatic worsening and exacerbation of the illness for unknown, disease-related reasons despite continued antipsychotic treatment can also occur. It is critical to understand that breakthrough symptoms are not always an indication of treatment failure. Therefore, as a first step, HCPs should identify all potential factors that could contribute to specific symptoms or symptom clusters and devise patient-specific mitigation strategies to optimize outcomes (Figure 1).

Table 2 Medication and dosing decision table for therapeutic dose monitoringReference Saklad17

Δ = change to different medication; ↑ = increase the dose; ↓ = decrease the dose.

Figure 1 Management of breakthrough psychotic symptoms in a patient receiving long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic in whom the LAI antipsychotic dose has been optimized. LAI = long-acting injectable; OAP = oral antipsychotic. *Off-label; based on PK modeling (no supporting clinical trial data available).Reference Saklad17 †Caution should be exercised with this strategy, because data on the safety of concomitant use of LAI and oral antipsychotics are limited, especially over extended periods of time.

Relevance of Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Aspects of Long-acting Injectable Antipsychotics

The PK and PD profiles of LAIs may contribute to patients experiencing psychotic breakthrough symptoms and should be considered when evaluating a patient. The slow, gradual dose titration inherent with the use of many LAIsReference Knox and Stimmel18, Reference Remington and Adams19 may mean that a patient will experience residual symptoms or require oral supplementation until the LAI dosage is optimized and the steady state of therapeutic blood concentration is achieved.Reference Citrome10, Reference Knox and Stimmel18 Both aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada®) and risperidone LAI (Risperdal Consta®) require 3 weeks of oral supplementation, whereas aripiprazole monohydrate (Abilify Maintena®) requires 2 weeks. A shorter, 1-week course of oral supplementation is needed with flupenthixol decanoate (Fluanxol®; Table 1). The proper administration of LAI antipsychotics is essential for establishing effective plasma concentrations. This includes sufficient shaking of atypical LAIs before injection (if required); Z-track injections for first-generation sesame oil preparations; choosing the appropriate needle size and administration site; injecting the LAI antipsychotic into the muscle, not fat tissue; and in some cases, administering the injection rapidly and without hesitation (because aripiprazole lauroxil is thixotropic, it may block the syringe if it is not injected rapidly; Table 1).Reference Citrome10, 20 If these steps are not taken during LAI administration, effective plasma concentrations may not be reached or sustained. In addition, missed LAI doses and their effect on blood concentrations must be accounted for and may require potentially restarting the initiation doses or administering booster injections (Table 3). Drug–drug interactions must also be taken into consideration as a potential cause of symptom breakthrough or psychotic symptom worsening.Reference Citrome10 Carbamazepine, a potent inducer of several drug-elimination pathways, can decrease plasma concentrations of risperidone or aripiprazole LAI, whereas the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors fluoxetine and paroxetine can increase the plasma concentrations of risperidone or aripiprazole LAI.Reference Citrome10, Reference Spina, Hiemke and de Leon21, 22 Furthermore, clozapine (serotonin dopamine-receptor antagonist) may impair clearance of risperidone, whereas the H2-receptor inhibitors cimetidine and ranitidine can increase its bioavailability.Reference Citrome10

LAI = long-acting injectable; PP1M = paliperidone palmitate once monthly; PP3M = paliperidone palmitate once every 3 months.

Carbamazepine is also known to increase the clearance rates of olanzapine, whereas fluvoxamine has been shown to increase the concentrations of olanzapine.Reference Citrome10 Strong CYP3A4/P-glycoprotein inducers (e.g., carbamazepine, rifampin, St. John’s wort) given concomitantly with LAI formulations of paliperidone palmitate may decrease the exposure to paliperidone.23, 24 If administration of a strong CYP3A4/P-glycoprotein inducer during the dosing interval is necessary, it is recommended that the patient be managed with paliperidone extended-release tablets.23, 24 Renal function is an important factor for paliperidone, such that LAI paliperidone palmitate (Invega Sustenna® and Invega Trinza®) is not recommended for use in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment, and only lower doses should be administered in patients with mild impairment.24 Dosage adjustments are recommended in patients who are treated concomitantly with aripiprazole and strong CYP3A4/CYP2D6 inducers and for those who are poor CYP2D6 metabolizers.Reference Citrome10 In poor CYP2D6 metabolizers, the dose of aripiprazole should be reduced. In patients who are CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers, it has been demonstrated that plasma levels of some LAIs (aripiprazole, haloperidol, risperidone, zuclopenthixol) are reducedReference Lisbeth, Vincent and Kristof25; however, the need to increase LAI dosing in these patients has yet to be established. In one small study of 85 patients taking risperidone, there was no indication that the subtherapeutic levels of the drug found in three CYP3D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers affected either the efficacy or tolerability of the LAI in these patients.Reference Ganoci, Lovric and Zivkovic26 Modeling of the interaction between CYP2D6 inhibitors and oral aripiprazole suggests that dose alteration is not required for courses of CYP2D6 inhibitors lasting ≤2 weeks.20, 22 Therefore, the dose of LAI should not be automatically adjusted if a patient is on a short course of enzyme inducer or inhibitor (Supplemental Table 1); rather, the patient should be monitored for adverse effects and the dose increased only after persistent problems arise. An overview of clinically relevant drug interactions for first- and second-generation LAIs is shown in Supplemental Table 2. A more detailed description of the PK/PD properties and interactions of LAIs is reviewed elsewhere.Reference Baldelli, Clementi and Cattaneo14, Reference Meyer27–Reference Schoretsanitis, Spina, Hiemke and de Leon29

Management of Symptomatic/Breakthrough Illness: Practical Considerations

Clinical scenario: LAI antipsychotic-treated patient presenting with exacerbation of symptoms

Patients receiving LAI antipsychotics who experience acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms may present at a psychiatrist’s office or the emergency department. Upon presentation, it is imperative to determine whether a medical illness, substance use, psychiatric comorbidity, relevant stressors, or nonadherence to treatment could explain the exacerbation. It is also crucial to assess which LAI the patient was given and, if possible, why the patient was started on an LAI (e.g., patient choice, poor adherence, prevention of poor adherence, court order). Determining when the LAI was last administered is essential, as this information will indicate whether the patient had sufficient time to reach therapeutic plasma concentrations. The timing of LAI administration will also reveal whether the patient had sufficient time to stabilize on the LAI before the current exacerbation or relapse. Ascertaining whether the patient missed a dose or received doses with a relevant delay is crucial, because strategies for managing missed doses vary depending on the specific LAI (see Table 3 for specific instructions). To help alleviate psychotic symptoms, it may be possible to give the next LAI dose early (off-label) or to increase the dose, depending on the release properties and dosing windows of the LAI. The HCP should determine whether acute oral supplementation is necessary based on the severity of the acute symptoms. Additional components of the evaluation should include relevant medical history, such as whether the patient presents episodically (exacerbations) or if the patient is always symptomatic (i.e., has residual symptoms), and whether any key medical or psychiatric comorbidities require attention. Identifying current symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depressive, psychotic, self-harm, suicidality), their duration, and whether there has been a significant increase in psychopathology will also help guide management. Certain lifestyle factors may also be relevant, such as (in the case of olanzapine LAI) smoking.Reference Heres, Kraemer, Bergstrom and Detke30 A list of pertinent questions that could be posed to the patient, caregiver, or HCP is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 Key questions asked by health-care providers to ascertain the etiology of breakthrough symptoms

AE = adverse event; LAI = long-acting injectable; OAP = oral antipsychotic; PP1M = paliperidone palmitate once monthly; PP3M = paliperidone palmitate once every 3 months.

Table 4 also summarizes actions that the clinician should consider based on the response to these questions and whether the corresponding features may be related to breakthrough psychotic symptoms. Figure 1 shows a decision tree regarding adaptation of management strategies for symptom breakthrough in patients receiving an LAI. For example, potential causes of breakthrough psychotic symptoms that may need to be addressed can include treatment nonadherence to LAIs, OAPs, non-antipsychotic comedications, and inappropriate or inadequate dosing, including initiating treatment incorrectly and other medication errors. Other causes of breakthrough psychotic symptoms can include AEs; treatment resistance or failure; alcohol or drug abuse or misuse; possible stressors present in the patient’s life, including legal issues; and/or psychosocial issues unrelated to relapse, including unstable living conditions, financial pressures, and stressors induced by the family environment, caregivers, or workplace. Difficulties accessing treatments or care would further complicate the management of breakthrough psychotic symptoms and should be improved or resolved if possible. In cases where substance abuse is a contributing factor to breakthrough symptoms, symptomatic management with either OAPs or benzodiazepines can be implemented until concentrations of the offending drug decrease. Psychoeducation and referral for substance abuse treatment can also be considered. If the symptom exacerbation is not caused by pharmacologic issues, then nonpharmacologic resolutions should be evaluated and sought. For example, therapy and family treatment sessions, lifestyle coaching, cognitive behavior therapy and rehabilitation, and acute pharmacologic support may still be necessary. If the etiology of the breakthrough symptoms is pharmacologic, the clinician should work to determine the efficacy of the patient’s treatment. The clinician should also consider whether the optimal dosage is being used and whether the efficacy outcome is sufficient (and in which domains). Some patients may require higher or lower doses to obtain optimal benefit, or they may require shorter intervals between doses (off-label). However, caution should be exercised to avoid overdosing and underdosing. Because higher doses may increase the incidence of AEs, regular and continuous supervision and reassessment is considered essential to identify and maintain the lowest dose level that is compatible with adequate symptom control. It is important to consult the prescribing information for LAIs for their recommended dosing; drug manufacturers can also be contacted for additional information on file, if needed (Table 1).

If causal factors for symptom exacerbation cannot be identified quickly enough, the addition of an OAP—ideally the same agent given in the LAI formulation—may be needed as an acute measure (Figure 1). The benefit of adding a different antipsychotic, although done frequently in clinical care, is not supported by high-level evidence based on randomized controlled trials.Reference Correll, Rubio and Inczedy-Farkas31–Reference Correll, Rummel-Kluge and Corves33 This even seems to apply to clozapine, for which there is limited and inconsistent evidence of benefit when included as part of a polypharmacy regimen.Reference Galling, Roldan and Hagi32, Reference Fleischhacker and Uchida34 The coadministration of an OAP with an LAI formulation of the same antipsychotic should be intended as a transient measure (off-label), and the efficacy and safety of this strategy should be assessed within 1 to 2 weeks. However, caution should be exercised with this strategy, because data on the safety of concomitant use of LAI and OAPs are limited, especially over extended periods of time. If addition of the OAP is successful, the time of regained stability can be used to adjust the LAI administration, dose, or dosing interval (off-label) to optimize LAI treatment; to adjust pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic treatments for the core disorder or comorbidities; or to address any other identified reason for symptom exacerbation. If the patient is sufficiently stable, a slow taper of the OAP can be attempted. If addition of the OAP and concurrent optimization of the LAI antipsychotic treatment do not sufficiently stabilize the patient, if symptoms reappear after stopping the OAP, or if other potential causes cannot be identified or addressed adequately, the patient may not be responding to treatment, and a switch of the adjunctive OAP or switch of the LAI may need to be considered.

During this entire process, it is critical that there be appropriate communication among treatment providers, the patient, the patient’s family or partner, and HCPs in different treatment settings (if the patient requires stabilization in an inpatient setting). Furthermore, the multidisciplinary nature of treating patients with schizophrenia highlights the importance of organizations and disciplines working as a team. For example, a patient with schizophrenia often receive care from multiple psychiatric teams (i.e., inpatient setting, community mental health, and crisis home treatment teams) as well as a general practitioner. Therefore, information pertaining to a patient’s condition and treatment should be readily communicated among these HCPs.Reference Haddad, Brain and Scott35 The treatment plan and details about LAI administration with or without OAP supplementation, the goals and steps of further management of the OAP, and any other aspect of the management should be clearly communicated with the patient and everyone involved in his or her care.

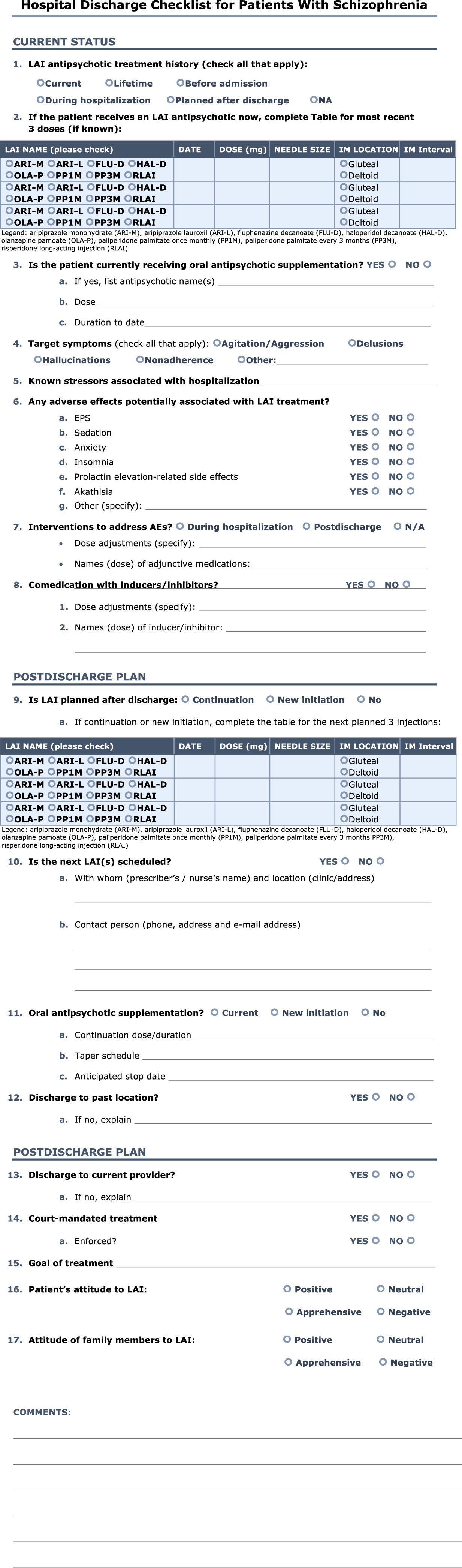

If the patient was stabilized in an inpatient setting, a discharge checklist could be used to facilitate communication and minimize the risk of future breakthrough psychosis or symptomatic worsening (Figure 2). Details regarding the stabilization, including the source of the problem, intervention, and follow-up, should be noted in the patient’s medical record and communicated to the patient and to his or her caregivers and HCPs. Medication reconciliation and discussion of, and agreement with, a recovery plan with all HCPs should be carried out. The patient and caregiver(s) should be provided with clear, detailed outpatient discharge instruction. Importantly, continuity of care should be facilitated by sharing the recovery plan with the patient’s current HCPs. Counseling and reflection with the patient and caregivers on the cause and consequences of this exacerbation would be advantageous to the patient’s outcome. Furthermore, combining nonpharmacologic with pharmacologic interventions, such as discussing the patient’s goals and how to prevent a future episode of breakthrough symptoms, can benefit the patient by helping him or her to achieve goals and improve overall prognosis.

Figure 2 Hospital discharge checklist for patients with schizophrenia.

Future Directions and Limitations

It should be noted that the recommendations provided in this article are based on available clinical, PK, and dosing data that are supplemented with clinical experience. The recommendations do not represent a formal consensus statement and therefore were not subjected to the explicit methodology commonly used to identify areas of agreement and disagreement among experts. The paucity of data regarding management strategies in response to patients experiencing breakthrough symptoms while undergoing LAI treatment underscores the need for future research, and in particular well-designed studies that examine the outcome of increasing LAI dose, switching LAIs, or supplementing the LAI with a low dose of the corresponding oral formulation in patients with symptom exacerbation. As such data become available, it is hoped that a formal guideline-consensus process based on a broader evidence base that may change or sharpen the currently made recommendations will be possible.

Summary

This article provides a framework and action plan for HCPs who manage patients treated with LAI antipsychotics who present with breakthrough psychosis and symptomatic worsening. Management options aimed at optimizing the disease prognosis and patient outcome include first ruling out or addressing medical or substance use as a contributing factor, identifying and addressing potential stressors, optimizing nonpharmacologic treatments, treating medical and psychiatric comorbidities, ensuring proper LAI administration technique, addressing missed LAI doses or lack of steady state, and increasing the dose of LAIs or shortening their injection intervals (off-label). If these strategies do not work sufficiently with frequent monitoring for efficacy and safety, supplementing the LAI with a low dose of the corresponding OAP formulation for fast symptom control may need to be considered (off-label). Caution should be exercised with this strategy, because data on the safety of concomitant use of LAI and OAPs are limited, especially over extended periods of time. If symptoms abate, optimizing the LAI therapy and addressing any other factors potentially related to the symptomatic exacerbation should be continued, and slowly discontinuing the OAP can be attempted. If symptoms continue or worsen despite addition of the OAP, if symptoms recur after stopping the OAP, and/or if addressing other factors potentially related to the breakthrough symptoms is insufficient, it may be necessary to switch the OAP or the LAI. However, regardless of the management plan, it must be documented and communicated clearly so that continuity of care is assured. Any strategies that are successful in restabilizing patients receiving LAI antipsychotic therapy who presented with breakthrough psychosis or symptomatic worsening should be retained and repeated in the event of future destabilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, Shaylin Shadanbaz, PhD, and Lynn Brown, PhD, for their writing and editorial assistance, which is supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC.

Funding

This study was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC.

Disclosures

Christoph Correll is on the boards of Alkermes, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Teva. He holds consultancy positions with Alkermes, Allergan, the Gerson Lehman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, Medscape, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, Rovi, Sunovion, Takeda, and Teva, and has provided expert testimony for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka. He has received grants or has grants pending from Janssen, Neurocrine, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the Bendheim Foundation, Takeda, and the Thrasher Foundation; he has received payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sunovion, and Takeda; and he has received payment for manuscript preparation from Medscape. In addition, travel, accommodations, meeting, and other expenses unrelated to the activities listed have been paid to Dr. Correll.

Jennifer Kern Sliwa reports personal fees from Johnson & Johnson and personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, outside the submitted work.

Dean Najarian reports personal fees from Johnson and Johnson and personal fees from Johnson and Johnson, outside the submitted work.

Stephen Saklad has received personal fees and acted as a consultant for Alkermes, Otsuka/Lundbeck, Jazz, NCS Pearson, and Takeda. He also sits on the advisory boards of and has delivered lectures for Alkermes, Neurocrine, and Otsuka/Lundbeck. He is a committee member (no financial support) of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP), and a board member and Treasurer of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists Foundation (CPNPF).

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918001098