Introduction

Manic symptoms below the threshold for hypomania (mixed features) are prevalent in people with major depressive disorder (MDD).Reference Judd and Akiskal 1 – Reference Zimmermann, Brückl and Nocon 7 In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS–R) study, a nationally representative, face-to-face, household survey of the U.S. population conducted between February of 2001 and April of 2003, nearly 40% of study participants with a history of MDD had subthreshold hypomania (defined as the presence of three or more manic symptoms).Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 Previous reports suggested that, compared to pure major depression, major depressive disorder with mixed features is associated with greater illness severity,Reference Perlis, Uher and Ostacher 8 – Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 increased frequency of recurrent depressive episodes,Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 , Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 increased risk of suicide attempts,Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 , Reference Zimmermann, Brückl and Nocon 7 , Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 – Reference Popovic, Vieta and Azorin 13 a high frequency of substance abuse,Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 , Reference Zimmermann, Brückl and Nocon 7 , Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 and greater functional impairment.Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 , Reference Benazzi and Akiskal 6 , Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 MDD with mixed features has recently been endorsed as a clinically distinct and valid entity by its inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5h ed. (DSM–5). 14

Lurasidone is an atypical antipsychotic agent with high affinity for D2, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT7 receptors (K i =1, 0.5, and 0.495 nM, respectively).Reference Ishibashi, Horisawa and Tokuda 15 In animal models, the antidepressant effect of lurasidone has been shown to be mediated in part by antagonist activity at the 5-HT7 receptor.Reference Hedlund 16 – Reference Cates, Roberts and Huitron-Resendiz 17 Lurasidone has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression), both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate.Reference Loebel, Cucchiaro and Silva 18 , Reference Loebel, Cucchiaro and Silva 19 A recent placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of lurasidone for MDD with subthreshold hypomanic symptoms.Reference Suppes, Silva and Cucchiaro 20

Symptomatic remission and reduction in functional impairment is considered necessary for meaningful recovery from psychiatric disorders.Reference Tohen, Frank and Bowden 21 – Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 A recent study evaluated recovery in bipolar depression based on rates of combined symptomatic and functional remission sustained over time.Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 A majority of patients with bipolar depression initially treated with lurasidone in the acute phase attained recovery status during the 6-month continuation study, and treatment with lurasidone (vs. placebo) earlier in the course of a bipolar depressive episode increased the likelihood of subsequent recovery. The objectives of our post-hoc analysis were to investigate the proportion of, and predictors for, combined symptomatic and functional remission at short-term (6 weeks) and extension (3 months) study endpoints among patients with major depressive disorder associated with subthreshold hypomanic symptoms (mixed features).

Methods

A post-hoc analysis was conducted using data from a previously reported double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trial in patients with major depressive disorder associated with subthreshold hypomanic symptoms (mixed features) (Clinicaltrials.gov, no. NCT01421134),Reference Suppes, Silva and Cucchiaro 20 which was followed by a 3-month open-label extension study with lurasidone (Clinicaltrials.gov, no. NCT01423253). The present study was approved by the institutional review board at each investigational site and was conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use–Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

This study enrolled outpatients 18–75 years of age diagnosed with major depressive disorder who were experiencing a major depressive episode (based on DSM–IV–TR criteria), with a score >26 on the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)Reference Montgomery and Åsberg 24 at both the screening and baseline visits. Diagnosis was confirmed by an experienced and qualified rater using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Disorders–Clinical Trial version (SCID–CT) modified to record the presence of mixed (hypomanic) symptoms.Reference First, Williams, Spitzer and Gibbon 25 In addition, patients were required to have two or three of the following manic symptoms, on most days, for at least 2 weeks prior to screening: elevated or expansive mood, inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, more talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking, flight of ideas or racing thoughts, increased energy, increased or excessive involvement in activities with a high potential for negative consequences, and decreased need for sleep. Independent external reviewers verified the diagnoses of all study participants, based on audiotaped recordings of diagnostic interviews conducted by site-based investigators.

Study design

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose study enrolled a total of 211 patients at 18 sites in the United States (n=62 patients) and at 26 sites in Europe (n=149 patients) between September of 2011 and October of 2014. After a washout period of at least 3 days, patients were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to 6 weeks of treatment with lurasidone or placebo. Study medication was taken once daily in the evening with a meal or within 30 minutes after eating. Patients assigned to receive lurasidone were treated with 20 mg/day for days 1–7. Patients were dosed flexibly, in the range of 20–60 mg/day, starting on day 8. The U.S. patients who completed the 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, core study were eligible to participate in an open-label, 3-month extension study, where lurasidone was flexibly adjusted (i.e., 20, 40, or 60 mg/day), based on clinical judgment, in order to optimize efficacy and tolerability.

Outcomes

The MADRS is a 10-item, clinician-rated assessment of severity of depression, with higher scores associated with greater severity of depression.Reference Montgomery and Åsberg 24 The Clinical Global Impressions Severity subscale (CGI–S) score rates overall illness severity on a 7-point scale, with higher scores associated with greater illness severity.Reference Guy 26 The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)Reference Sheehan, Hamett-Sheehan and Raj 27 is a well-established self-rated scale designed to assess level of functional impairment across three major functional domains, in which patients rate the extent to which (1) work, (2) social life or leisure activities, and (3) home life or family responsibilities are impaired by mood symptoms on 10-point visual analog scales (0=“not at all,” 1–3=“mildly,” 4–6=“moderately,” 7–9=“markedly,” and 10=“extremely”), with higher scores reflecting greater functional impairment. MADRS and CGI–S scores were assessed at core baseline, week 6 (end of double-blind core phase), and at months 1, 2, and 3 of the extension study. SDS scores were assessed at core baseline, week 6, and at months 1 and 3 of the extension study. We defined symptomatic remission as a MADRS total score <12 and functional remission as all SDS domain scores <3 (representing mild or absent functional impairment).Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 , Reference Sheehan, Hamett-Sheehan and Raj 27 Recovery was defined as the presence of both symptomatic remission (MADRS score ≤12) and functional remission (all SDS domain scores ≤3) at week 6 (“cross-sectional recovery”), and at both months 1 and 3 of the extension study (“sustained recovery”). Sensitivity analyses were performed using a MADRS score of <8 to assess rates of symptomatic remission and all SDS domain scores <2 to assess functional remission at week 6.

Statistical methods

In the present post-hoc analysis, a logistic regression model was applied to evaluate the effect of lurasidone on attaining cross-sectional recovery (defined as combined symptomatic and functional remission) at week 6. Evaluations of explanatory factors for cross-sectional recovery at week 6 and at month 3 of the extension study were conducted using multivariate logistic regression, controlling for treatment, baseline MADRS and SDS scores, and region. Predictors of sustained recovery at month 3 of the extension were not performed due to sample size limitations.

Moderator analyses were performed using a statistical interaction test in the logistic regression model to compare treatment effects in patients with two versus three protocol-specified manic symptoms at study baseline. Exploratory analyses were performed to evaluate rates of sustained recovery among patients enrolled at U.S. sites. Association between symptomatic remission and functional remission was assessed using the phi (ϕ) coefficient. The concordance between these two remission outcomes controlling for treatment was evaluated using overall kappa (κ).

Results

A total of 211 patients were randomized to receive once-daily lurasidone 20–60 mg (n=109) or placebo (n=102). Of these, 208 patients (lurasidone n=108, placebo n=100) received at least one dose of study medication and comprised the intent-to-treat population. Of the 59 patients enrolled at U.S. sites, 52 patients (89.7%) completed the 6-week, double-blind, randomized phase, of whom 48 (lurasidone-to-lurasidone n=29; placebo-to-lurasidone n=19) enrolled in the 3-month open-label extension study.

The demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. At week 6, a significantly higher proportion of lurasidone-treated patients met the criteria for cross-sectional recovery using the MADRS total score <12 and all SDS domain scores <3 criteria (31.1%, 33/106) compared to the placebo group (12.2%, 12/98, p=0.002, number needed to treat [NNT]=6, last observation carried forward [LOCF]) (Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis using an MADRS total score <8 and all SDS domain scores <2, the rates of cross-sectional recovery at week 6 were 19.8% (21/106) for lurasidone versus 10.2% (10/98) for placebo (p<0.05, NNT=11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cross-sectional recovery at week 6 (LOCF, intention-to-treat [ITT] population). *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Four ITT subjects had missing SDS data. A logistic regression model that included terms for treatment, region, and baseline MADRS and SDS scores was applied. Cross-sectional recovery at week 6 was defined as combined symptomatic and functional recovery at week 6.

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (safety population)

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the lurasidone group (49.1%, 53/108) than in the placebo group (23.0%, 23/100) met the symptomatic remission criteria (MADRS<12) at week 6 (p<0.001, NNT=4) (Figure 2). Using a more stringent MADRS score criterion (MADRS ≤ 8), the proportion of lurasidone-treated patients attaining symptomatic remission was also significantly higher (36.1%, 39/108) compared to the placebo group at week 6 (17.0%, 17/100; p=0.001, NNT=6) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Symptomatic remission at week 6 (LOCF, ITT population). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. A logistic regression model that included terms for treatment, region, and baseline MADRS score was applied.

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the lurasidone group than in the placebo group met the functional remission criteria (all SDS domain scores ≤ 3) at week 6, with 38.7% (41/106) in the lurasidone group versus 18.4% (18/98) in the placebo group (p=0.002, NNT=5). Lurasidone was also superior to placebo in achieving functional remission across the three SDS domains (SDS domain ≤ 3): work/school (p=0.001, NNT=3); social life (p<0.001, NNT=4); and family life (p<0.001, NNT=4). Using a more stringent SDS score criterion (all SDS domain scores ≤ 2), the proportion of patients achieving functional remission remained significantly higher in the lurasidone group (31.1%, 33/106) compared to the placebo group (14.3%, 14/98; p=0.005, NNT=6) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 SDS functional remission at week 6 (LOCF, ITT population). **p<0.01. Four ITT subjects had missing SDS data. A logistic regression model that included terms for treatment, region, and baseline MADRS and SDS scores was applied.

Reduction in depressive symptoms from baseline to week 6 mediated functional remission at week 6 (p<0.001, χ2=39.58, df=1). The concordance between symptomatic remission and functional remission was 77.9% (159/204, overall κ coefficient controlling for treatment=0.47, 95% confidence interval [CI 95%]=[0.35, 0.60]; ϕ=0.52). Demographics and baseline MADRS and SDS scores had been assessed but were found to be statistically nonsignificant predictors for cross-sectional recovery at week 6.

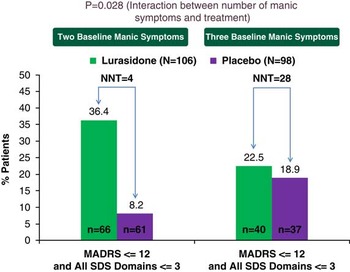

The protocol-specified number of manic symptoms at baseline was a significant moderator of cross-sectional recovery at week 6 (p=0.028 for treatment-by-number of manic symptoms at baseline). The effect size for attaining cross-sectional recovery at week 6 with lurasidone treatment (vs. placebo) was significantly higher (p=0.028) in patients with two manic symptoms (lurasidone 36.4%, 24/66; placebo 8.2%, 5/61; NNT=4) compared to three manic symptoms (lurasidone 22.5%, 9/40; placebo 18.9%, 7/37; NNT=28) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Significant moderator of cross-sectional recovery at week 6 between lurasidone and placebo: baseline number of manic symptoms in treatment of MDD with mixed features. *p<0.05. Four ITT subjects had missing SDS data. A logistic regression model that included terms for treatment, region, baseline MADRS and SDS scores, number of manic symptoms, and number of manic symptom × treatment was applied. Cross-sectional recovery at week 6 was defined as combined symptomatic and functional recovery at week 6.

In the 3-month, open-label, extension study, among the U.S. lurasidone-to-lurasidone group patients, the rates of recovery increased from 27.6% (8/29) at week 6 to 34.6% (9/26) at month 1, and to 41.7% (10/24) at month 3 of the extension study. A similar trend was observed for the placebo-to-lurasidone group, whose recovery rates increased from 5.3% (1/19) at week 6 to 27.8% (5/18) and 37.5% (6/16) for the month 1 and month 3 endpoints, respectively (p<0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cross-sectional recovery over the acute and extension treatment periods (U.S. sites only). *p<0.05 (increasing linear slope). Lurasidone-to-lurasidone: lurasidone in the 6-week randomized phase followed by flexible dosing of lurasidone in the 3-month extension study. Placebo-to-lurasidone: placebo in the 6-week randomized phase followed by flexible dosing of lurasidone in the 3-month extension study. Cross-sectional recovery was defined as combined symptomatic and functional recovery at week 6 in the core phase and at months 1 and 3 of the extension study.

The proportions of lurasidone-treated patients achieving “sustained recovery,” defined as meeting criteria for combined symptomatic remission (MADRS<12) and functional remission (all SDS domain scores<3) for both months 1 and 3 of the extension study, were 20.8% (5/24) and 12.5% (2/16) in the lurasidone-to-lurasidone and placebo-to-lurasidone groups, respectively (Figure 6). The proportion of patients attaining symptomatic remission sustained at both months 1 and 3 were 45.8% (11/24) in the lurasidone-to-lurasidone group and 31.3% (5/16) in the placebo-to-lurasidone group. The proportions of patients attaining functional remission sustained for both months 1 and 3 were 36.0% (9/25) in the lurasidone-to-lurasidone group and 31.3% (5/16) in the placebo-to-lurasidone group.

Figure 6 Recovery: sustained symptomatic and functional remission (U.S. sites only). Lurasidone-to-lurasidone: lurasidone in the 6-week randomized phase followed by flexible dosing of lurasidone in the 3-month extension study. Placebo-to-lurasidone: placebo in the 6-week randomized phase followed by flexible dosing of lurasidone in the 3-month extension study. “Sustained recovery” was defined as meeting criteria for both symptomatic and functional remission at both months 1 and 3 of the extension study.

Reduction in depressive symptoms from core study baseline to month 3 was significantly associated with functional remission at month 3 of the extension study (p=0.006, χ2=7.65, df=1; LOCF). The concordance between symptomatic remission and functional remission at month 3 (LOCF) was 65.9% (29/44) (overall κ coefficient controlling for treatment=0.31, CI 95%=[0.03, 0.59]; ϕ=0.31). The change in CGI–S scores from core study baseline to month 3 was significantly associated with cross-sectional recovery at month 3 (p=0.002, χ2=9.32, df=1).

Discussion

The present research is the first study, to our knowledge, of recovery in major depressive disorder with subthreshold hypomanic symptoms (mixed features), as defined by the integration of symptomatic remission and functional improvement.Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 While the construct of “recovery” from episodes of mood disorder has often been defined based mainly, if not solely, on the basis of affective symptom resolution sustained for at least 8 weeks,Reference Tohen, Frank and Bowden 21 , Reference Goldberg, Perlis and Ghaemi 28 a more rigorous definition of “recovery” that incorporates the absence of functional impairment was proposed over 30 years ago in the Research Diagnostic Criteria.Reference Spitzer, Endicott and Robins 29 However, rigorous definitions of “recovery” that incorporate both symptomatic remission and functional improvement as indicators of treatment success have been used in only a handful of outcome studies (e.g., the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study) by Solomon et al.Reference Solomon, Fiedorowicz and Leon 30 and Loebel et al.Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23

Judd et al.Reference Judd, Schettler and Rush 31 proposed a definition of major depressive episode recovery as an 8-week period free of all symptoms associated with the previous major depressive episode (asymptomatic recovery). In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, which enrolled outpatients with nonpsychotic major depressive disorder,Reference Trivedi, Rush and Wisniewski 32 the primary outcome was symptomatic remission defined as a HAM–D score <7. A total of 27.5% of patients achieved remission after 8 weeks of treatment with citalopram (level 1 treatment). In the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP–BD) study in patients with major depressive episode associated with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, the primary outcome was durable recovery (defined as at least 8 consecutive weeks of euthymia—no more than two depressive or two manic symptoms).Reference Sachs, Nierenberg and Calabrese 33 For patients receiving a mood stabilizer plus adjunctive antidepressant therapy and a mood stabilizer plus matching placebo, a total of 23.5 and 27.3% of patients, respectively, achieved recovery. In a recent 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of olanzapine in bipolar I depression, the rates of remission (defined as MADRS<8) and recovery (defined as MADRS<12 for >4 weeks plus treatment completion) for olanzapine were 38.5% (vs. 29.2% for placebo) and 13.7% (vs. 9.4% for placebo), respectively.Reference Tohen, McDonnell and Case 34 All of these definitions were based on asymptomatic remission for 6- to 8-week durations (asymptomatic recovery).

In our post-hoc analysis of a placebo-controlled trial, lurasidone was found to significantly improve rates of “cross-sectional recovery” (i.e., a combination of symptomatic remission and functional remission) at the 6-week study endpoint, with moderate effect size (NNT=6). In the 3-month open-label extension of the study (limited to patients enrolled at U.S. sites), sustained recovery was attained by 20.8% of patients who continued on lurasidone in the extension study, and by 12.5% of patients who switched from placebo to lurasidone in the extension study. Higher cross-sectional recovery rates were observed for lurasidone-to-lurasidone patients (41.7%) compared to placebo-to-lurasidone patients (37.5%) after 3 months of extension-study treatment. Rates of recovery increased over time in patients treated with both lurasidone and placebo in the acute and extension studies, suggesting that responsivity to lurasidone was not reduced based on initial assignment to placebo.

The “cross-sectional” and “sustained recovery” rates reported for lurasidone in this post-hoc analysis using multidimensional recovery criteria are at least similar and may be higher than the recovery rates reported in prior mood-disorder studies that used less stringent criteria at generally shorter treatment durations of 6–8 weeks (as noted above). Our findings therefore support the effectiveness of lurasidone in attainment of recovery, rigorously defined, in patients with a severe form of MDD.

While both symptomatic and functional improvement are important components of full recovery,Reference Tohen, Frank and Bowden 21 , Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 , Reference Sheehan and Sheehan 35 – Reference McIntyre, Lee and Mansur 40 and may be linked, as demonstrated in several studies,Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 , Reference Sheehan and Sheehan 35 – Reference Bijl and Ravelli 38 they are not necessarily always coincident.Reference Tohen, Frank and Bowden 21 , Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 , Reference Sheehan and Sheehan 35 – Reference Mancini, Sheehan and Demyttenaere 37 , Reference McIntyre, Lee and Mansur 40 – Reference Mojtabai 43 The observation that functional recovery often lags behind symptomatic or syndromal recoveryReference van der Voort, Seldenrijk and van Meijel 41 may account for this lack of coincidence in the components of recovery. Findings from this analysis indicated that there was a moderately high level of concordance between symptomatic remission and functional remission at the endpoints of both the core (77.9%) and extension (65.9%) studies.

In our study, functional remission at week 6 was found to be mediated through improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to week 6, while the overall improvement in CGI–S score mediated recovery at the extension-study endpoint. These results are consistent with a recent study by Rajagopalan and colleaguesReference Rajagopalan, Bacci, Wyrwich, Pikalov and Loebel 44 which found that functional improvement in patients with bipolar depression was mediated through the reduction of depressive symptoms.

We defined mixed features in our study as the presence of two or three protocol-specified manic symptoms for at least 2 weeks prior to screening. Previous reports have suggested that a poorer prognosis and greater functional impairment were associated with mixed mood symptoms of opposite polarity (e.g., mixed mania) compared to unipolar depression.Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 2 , Reference Nusslock and Frank 11 , Reference Smith, Forty and Russell 12 , Reference Vieta and Valentí 45 In this analysis, we found that number of manic symptoms at baseline was a significant moderator for recovery (cross-sectional) at week 6, using a statistical interaction test in the full analysis sample (N=204). Patients with two manic symptoms (occurring on most days for at least 2 weeks prior to screening) had a greater likelihood of attaining cross-sectional recovery at week 6 (NNT=4 for lurasidone vs. placebo) than subjects with three manic symptoms (NNT=28 for lurasidone vs. placebo). However, we note that, due to the limited number of concomitant manic symptoms present in each subsample, together with their small size and variability in treatment response, definitive conclusions are precluded regarding whether subthreshold manic symptoms during major depression can attenuate treatment efficacy via a gradient or threshold effect. Interestingly, the proportion of lurasidone-treated patients attaining combined symptomatic and functional remission at week 6 was similar in patients with two subthreshold hypomanic symptoms (36.4%) compared to lurasidone-treated patients with bipolar depression (33.3%).Reference Loebel, Siu, Rajagopalan, Pikalov, Cucchiaro and Ketter 23 Further research is needed to confirm these exploratory findings, which suggest that the number and possibly the type of manic symptoms may moderate the likelihood of symptomatic and functional remission in the treatment of MDD with mixed features.

Several limitations of this post-hoc analysis should be noted. The criteria for mixed features in our study were similar to, but not exactly the same as, the DSM–5 mixed-features specifier. 14 The moderator analysis was based on a statistical interaction test utilizing a relatively small full analysis sample. We also note that only patients at U.S. sites were eligible for the extension study (which was not conducted outside the States), which limited the sample size for the extension study. While we assume that the extension study recovery data presented here are generalizable to the entire study population, this cannot be definitively established. These findings should therefore be considered preliminary and exploratory. Further investigations to confirm the long-term effectiveness of lurasidone in this novel patient population are thus warranted.

Conclusions

In this post-hoc analysis of a placebo-controlled study with open-label extension, involving patients with MDD and subthreshold hypomanic symptoms (mixed features), lurasidone was found to have significantly improved the rate of recovery at 6 weeks (vs. placebo), which was sustained after an additional 3 months of extension-study treatment. The presence of two (vs. three) manic symptoms moderated recovery at the acute study endpoint. These results underscore the importance of assessing combined symptomatic and functional remission in the evaluation of long-term recovery outcome. Further investigation and validation of our criteria for recovery and predictors of recovery in patients with MDD with mixed features are warranted.

Disclosures

Joseph F. Goldberg reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Merck, from Takeda–Lundbeck, from Vanda Pharmaceuticals, from WebMD, and from Medscape outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Goldberg has published a book with American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. with royalties paid.

Cynthia Siu reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Pfizer Inc. and the Chinese University of Hong Kong outside the submitted work.

Daisy Ng-Mak reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Chien-Chia Chuang reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Krithika Rajagopalan reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.

Antony Loebel reports personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. during the conduct of the study.