Article contents

“The Earth Becomes Flat”—A Study of Apocalyptic Imagery

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 June 2009

Extract

The thirty–fourth chapter of the Greater Bundahišn, which is the fullest eschatological account within this important Middle Persian text, ends on an extremely peculiar note. Its final verse states:

This also is said [in the Avesta]: “The earth becomes flat, without a crown and without a seat. There are no mountain peaks nor hollows, nor are ‘up’ and ‘down’ preserved.”

Information

- Type

- Metaphors of Revolution

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 1983

References

1 Greater Bundahišn 34.33 (= Indian Bundahišn 30.33). TD Manuscript, page 228, lines 3–5: ēnīz guft kū: ēn zamīg *anabesar (for ‘n’pyšl) ud anišast ud hāmōn be bawēd. kōf čagād gabr udul dārišn frōd dārišn nē bawēd. (Asterisk here and elsewhere indicates author's emendations of the manuscript.)

2 Widengren, Geo, Die Religionen Irans (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1966), 206.Google Scholar

3 West, E. W., Pahlavi Texts (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1880), I, 129, n. 8.Google Scholar

4 Zad Spram 7.1. The other major treatment of mountains within the Pahlavi corpus, Mēnōg ī Xrad 56, has no account of their origin, although the mention of Mēnōg ī Xrad 56.6 that mountains are “smiters of Ahriman and the demons” (zadār[ān] ī Ahreman ud dewān) seems to indicate that text views them as a part of the good creation.

5 Greater Bundahišn 6C.1 (= Indian Bundahišn 8.1). TD Manuscript, page 65, lines 12–14: sidīgar ardīg zamīg kard. čīyōn gannāg [mēnōg] andar dwārād. zamīg be zandēd. ān gōhr Ī kōf andar zamīg dād ēstād. pad wizandišn Ī zamīg ham zamān kōf ō Ī rawišn ēstād

6 Yasna 1.14, 2.14. Yasna 71.10 mentions a sacrifice to all mountains, within the context of a sacrifice to all good and holy creations made by Ahura Mazdā. Yašt 19.1–8, which gives an account of the creation of mountains, makes no mention of Aŋra Mainyu (= Pahlavi Ahriman), and depicts mountains in a wholly positive light.

7 Herodotos 1.131.

8 Moulton, James Hope, Early Zoroastrianism (London: Williams and Norgate, 1913), 403, n. 3;Google ScholarBenveniste, Emile, The Persian Religion according to the Chief Greek Texts (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1929), 106;Google ScholarLommel, Herman, Die Religion Zarathuštras nach dem Awesta dargestellt (Töbingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1930), 211.Google Scholar

9 Se Yasna 30.7, 32.7, 51.9; and such Pahlavi texts as the Pahlavi Rivayat to the Dādestan ī Dēnig 48.70; Dēnkart 3.169. On the dating of Zarathuštra, see my Priests, Warriors, and Cattle (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), 49, n.1.Google Scholar

10 Greater Bundahišn 34.18–19, 31–33 (= Indian Bundahišn 30.19–20, 31–33). TD Manuscript, page 225, lines 6–11; page 227, line 13 through page 228, line 5. pas ātaxš ud ērmān yazd ayōxšust andar kōfān ud garān widāzēnd. pad zamīg rōd hōmānāg ēstēd. pas harwisp mardōm andar ān ayōxšust widāxtag be widārēnd ud pāk be kunēnd. ud kē ahlaw āhaniš ōwōn sahēd čiyōn ka šīr Ī garm hamē rawēd. ka druwand āhaniš hamēwēnag sahēd kū andar ayōxšust widāxtag hamē rawēd.… ud Gočihr mār pad ān ayōxšust Ī widāxtag *sōzēd. ud ayōxšust andar ō dušōx tazēd. ān gandagīh ud rēmanīh andar zamīg kū dušōx būd, pad ān ayōxšust sōzēd. pāk bhawēd. ān *gabr[?] Ī ganāg mēnōg padiš andar dwared, pad ān ayōxšust gīrēd. an zamīg dušōx abāz ō frāxīh Ī gēhān āwarēnd, ud bawēd frašagird andar axw pad kāmag Ī gēhān āmarg tā hamē hamē rawišnīh. ēnīz guft kū: ēn zamīg *anabesar ud anišast ud hāmōn be bawēd. kōf čagād gabr ud ul dārišn frōd dārišn nē bawēd.

11 Greater Bundahišn 34.20–21 (= Indian Bundahišn 30.20–21). TD Manuscript, page 225, line 11 through page 226, line 1: pas pad ān ī mahist dōšāram harwisp mardōm ō ham rasēnd. pid pus ud brād hamāg dōst mard az mard pursēnd kū: ān and sāl kū būd hē ut pad ruwān dādestān čē būd. ahlaw būd hē ayāb ud druwand. Nazdist ruwān tan wēnēd, uš pursēd pad ān guft passox. mardōm[ān] āgenēn hamkārīh bawēnd, ud buland stāyišnīh ō Ohrmazd ō amahraspandān barēnd.

12 Theopompos (on whom, see Hans Breitenbach, Rudolf, in Der kleine Pauly (Munich: Alfred Druckenintiller, 1975) V, 727–30Google Scholar), is mentioned in the sentence which follows the passage cited below, but it is not clear how precisely Plutarch signaled his use of this author. Cumont, Franz, for instance, Textes et monuments figurés relatifs aux mystères de Mithra (Brussels: H. Lamartin, 1896–1899) II, 33–34, maintains that the passage under discussion here did not derive from Theopompos, but his arguments are not conclusive and the question remains open.Google Scholar

13 Windisch, H., Die Orakel des Hystaspes, Verhandelingen der koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen to Amsterdam, Afdeeling Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks, 28/3 (1929), 81.Google Scholar

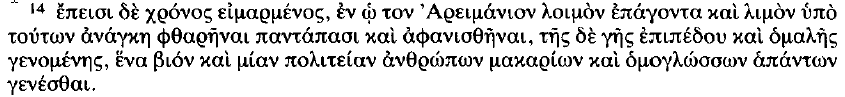

14

15 On the description of Iranian religion in the Isis and Osiris, see Moulton, , Early Zoroastrianism, 399–402;Google ScholarBenveniste, , Persian Religion, 69–117;Google ScholarBidez, Joseph and Cumont, Franz, Les mages Hellenisés (Paris: Les belles lettres, 1938) II, 70–79;Google ScholarGriffiths, J. Gwyn, Plutarch's De lside et Osiride (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1970), 470–82.Google Scholar

16 See, for instance, the Pahlavi Rivayat to the Dādestān ī Dēnig 48.94–96,Google Scholar translated in Zaehner, R. C., The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1961), 315, which explicitly notes the difference of opinion as to whether or not Ahriman was slain or merely rendered eternally powerless.Google Scholar

17 See the listing in Liddell, Henry George and Scott, Robert, Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 1073, and the sources listed therein.Google Scholar

18 E.g., Greater Bundahišn 34.23.

19 Dēnkart 3.327. Dresden manuscript, page 246, lines 13–15, 20–22: hād hamīh ī mardōm ud āniz ī wihān hamēndōšāramīh, awēšān ![]() ēk az did az wisistagīh ī dōšāram az āz ud xēšm ud arešk ud kēn čērīh ī andar padiz āzurdarīh ī dēwān ud xrad awēšān.… pad frašegird awardišnig ōstīgān. dōšāramīh ī mardōm āgenēn az ān be (sr'nmwyh') anēmēdīh ī dēwān az anasarīh [i] tuwān ī abar mardōm.

ēk az did az wisistagīh ī dōšāram az āz ud xēšm ud arešk ud kēn čērīh ī andar padiz āzurdarīh ī dēwān ud xrad awēšān.… pad frašegird awardišnig ōstīgān. dōšāramīh ī mardōm āgenēn az ān be (sr'nmwyh') anēmēdīh ī dēwān az anasarīh [i] tuwān ī abar mardōm.

20 Dēnkart 3.246. Dresden manuscript, page 202, lines 12–17: hād ka dādār Ohrmazd dām az ēk gōhr dahād mardōm az ēk pid zāyēnd. ēdiz kū tā dām hamgōhrīhiz rāy ēk ō did parwarēnd ud winnārēnd ud ayārēnd. ud mardōm ham zāyēnitārīhiz rāy ēk ēk ōy ī did pad xwēš dārēnd ud ![]() [?] mihrbān brādarān ēk abāg did nēkīh kunēnd. ēk az ōy ī did anāgīh be barēnd.

[?] mihrbān brādarān ēk abāg did nēkīh kunēnd. ēk az ōy ī did anāgīh be barēnd.

21 On this myth, and its derivation from Proto–Indo–European traditions, see Lincoln, , Priests, Warriors, and Cattle, 69–95, esp. 72, 76–77, 83.Google Scholar

22 There is some difficulty in the argument here, since the reform of Zarathuštra produced major changes in the pre–Zoroastrian creation account current in Iran. The latter must be reconstructed on the basis of (I) later Iranian evidence, (2) comparative Indic evidence, and (3) comparative evidence from the broader Indo–European sphere. On the basis of these, it is clear that both the Proto–Indo–European and Proto–Indo–Iranian cosmogony told that from the body of the first sacrificial victim (the Proto–Indo–European *Yemo, reflected in Iran by both Gayōmart and Yima) there issued, among other products, the three Indo–European social classes. Zoroastrian legend preserves this in two ways: first, in the description of how the ten or twentyfive races of man came from the semen posthumously emitted by Gayōmart, in which a racial system of classification is substituted for a system by social class; and second, in the legend of the three flights of Yima's royal xvarēnah (on which, see Priests, Warriors, and Cattle, 77–79). On the strength of these two variants, one can posit a pre–Zoroastrian tradition of the origin of social classes from the body of the first sacrificial victim, (whose Iranian name would have been Yima), much like the account in India (Rg Veda 10.90.11–12).Google Scholar

23 On the crown of the Achaemenid king, see the description in Curtius Rufus 3.3.19; Arrian 4.7.4; and the representations in the Persepolis reliefs. Note that Ammianus Marcellinus 18.5.6 calls the crown of a satrap his apex. On the cosmic significance of the crown in the Parthian period, see Widengren, , Die Religionen trans, 154.Google Scholar

24 avaēšam nōit vīduye yā savaitē ![]() ərəšvåŋhō. The view of Insler, S., The Gāthās of Zarathustra (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975), 29, 149Google Scholar, that ərəšvāŋhō, “the lofty,” refers to the gods, must be rejected, for ərəšva– never has this sense in Avestan, instead referring always to a group of mortals (Yasna 51.5, 51.11) or to an inanimate entity such as sovereignty (Yasna 44.9) or speech (Yasna 28.6). Zarathuštra's championing the cause of the poor and lowly is justly emphasized by Barr, Kaj, “Avestan drəgu–,

ərəšvåŋhō. The view of Insler, S., The Gāthās of Zarathustra (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975), 29, 149Google Scholar, that ərəšvāŋhō, “the lofty,” refers to the gods, must be rejected, for ərəšva– never has this sense in Avestan, instead referring always to a group of mortals (Yasna 51.5, 51.11) or to an inanimate entity such as sovereignty (Yasna 44.9) or speech (Yasna 28.6). Zarathuštra's championing the cause of the poor and lowly is justly emphasized by Barr, Kaj, “Avestan drəgu–, ![]() ,” in Studia Orientalia loanni Pedersen (Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard, 1943), 21–40,Google Scholar details of which must now be modified in light of Lommel, Herman, “Aw drigu, vātra and Verwandtes,” in Pratidānam: Indian, Iranian, and Indo–European Studies presented to Franciscus Bernardus Jacobus Kuiper, Heesterman, J. C., ed. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968), 127–33.Google Scholar The social thrust of the Gāthās had already been stressed by Meillet, Antoine, Trois conferences sur les Gāthās de l'Avesta (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1925), 65–68.Google Scholar

,” in Studia Orientalia loanni Pedersen (Copenhagen: E. Munksgaard, 1943), 21–40,Google Scholar details of which must now be modified in light of Lommel, Herman, “Aw drigu, vātra and Verwandtes,” in Pratidānam: Indian, Iranian, and Indo–European Studies presented to Franciscus Bernardus Jacobus Kuiper, Heesterman, J. C., ed. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968), 127–33.Google Scholar The social thrust of the Gāthās had already been stressed by Meillet, Antoine, Trois conferences sur les Gāthās de l'Avesta (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1925), 65–68.Google Scholar

25 The most important works on the Oracles of Hystaspes are Windisch, Die Orakel des Hystaspes, and Hinnells, John R., “The Zoroastrian Doctrine of Salvation in the Roman World: A Study of the Oracle of Hystaspes,” in Man and His Salvation: Studies in Memory of S. G. F. Brandon, Sharpe, Eric J and Hinnells, John R., eds. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1973), 125-48.Google Scholar A complete bibliography of the earlier literature is given in Hinnells, , “Zoroastrian Doctrine,” 126, n. 2.Google Scholar

26 Hinnells, , “Zoroastrian Doctrine,” 145ff.Google Scholar Strong arguments for an earlier date are advanced by Widengren, , Die Religionen Irons, 199Google Scholar, and Eddy, Samuel K., The King Is Dead (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961), 32–36.Google Scholar

27 God here appears under the name “Jupiter,” something which rules out a Jewish or Christian source behind Lactantius, and strongly indicates an Iranian original, for while Ahura Mazdā is frequently syncretized with Zeus or Jupiter, Jews and Christians never permitted such a move for their deities. See Windisch, , Die Orakel des Hystaspes, 75–77.Google Scholar

28 As argued by Eddy, , The King Is Dead, 17–19.Google Scholar

29 On Vištāspa, see Windisch, , Die Orakel des Hystaspes, 10–13.Google Scholar

30 Lactantius, , Divine Institutions 7.16.4, 10–12; 7.17.9: Aer enim vitiabitur, et corruptus ac pestilens feet modo importunis imbribus, modo inutili siccitate, nunc frigoribus, nunc aestibus nimiis, nec terra homini dabit fructum: non seges quicquam, non arbor, non vitis feret, sed cum in flore spem maximam dederint, in fruge decipient.… Tunc annus breviabitur et mensis minuetur, et dies in angustum coartabitur. Stellae vero creberimae cadent, ut caelum caecum sine ullis luminibus appareat. Montes quoque altissimi decident, et planis aequabuntur, mare innavigabile constituentur.… Plorabunt, et gement, et dentibus stridebunt, gratulabuntur mortuis, et vivos plangent.… Id erit tempus, quo justicia projicietur, et innocentia odio erit, quo mali bonos hostiliter praedabuntur. Non lex aut ordo aut militiae disciplina servabitur non canos quisquam reverebitur, non officium pietatis adgnoscet, non nexus aut infantiae miserebitur: confundentur omnia et miscebuntur contra fas, contra jura naturae.Google Scholar

31 Hinnells, , “Zoroastrian Doctrine,” 138–39.Google Scholar

32 Jāmāsp Nāmag 12–21, 26–28.Google Scholar Transliteration following Benveniste, Emile, “Une apocalypse pehlevi,” Revue de l'histoire des religions, 106 (07-08 1932), 352–53.Google Scholar ud hamāg Ēran sahr ō dast ī awēšān dušmenān rasēd. Anēr ud Ēr gumēzīhēnd ēdōn kū anērīh az ērīh paydāg nē bawēd ēr abāz anērīh ēstend. pad ān āwām ān ruwāngar ān ī driyōš farrox dārēnd driyōš xwad farrox nē bawēd. ud āzādān ud wuzurgān zīwandagīh abēmizag. ušān margīh ēdōn xwaš čīyōn pid wēdnišn ī frazand ud mādar duxtar pad kābēn duxt pad wahāg bē frawaxśēd [?] pus pidar ud mādar zanēd uš andar zīwandagīh az kadagxwadāyīh ![]() kunēd. keh brādar meh brādar zanēd uš xwāstag aziš stānēd uš xwāstag rāy zūr gowēd. zan gyān pad margarzān dahēd. ērīg ō paydāgīh rasēd. * * * ud andarwāy adišuflag [?] ud sard wād ud garm wād wāzēd. bar ī urwarān kem bawēd zamīg az barē bē šawed. būmčandag wasīgar bawēd was awēranīh bē kunēd.

kunēd. keh brādar meh brādar zanēd uš xwāstag aziš stānēd uš xwāstag rāy zūr gowēd. zan gyān pad margarzān dahēd. ērīg ō paydāgīh rasēd. * * * ud andarwāy adišuflag [?] ud sard wād ud garm wād wāzēd. bar ī urwarān kem bawēd zamīg az barē bē šawed. būmčandag wasīgar bawēd was awēranīh bē kunēd.

33 Zand ī Vohuman Yasn 4.35–37Google Scholar (= 2.38–39 in West, Pahlavi Texts, I). Text from Anklesaria, B. T., Zand ī Vohuman Yasn (Bombay: n.p., 1957) page 27, line 4 through page 28, line 5: xwurdagān duxt ī āzādagān wuzurgān mogmardān pad zanīh gīrēnd. āzādagān ud wazurgān ud mogmardān be ō škōhīh bandagīh rasēnd. ud zanīh ud zwurdag be ō wuzurgīh ud pādixšāyīh rasēnd. ud ačāragān xwurdagān be ō pēšgāhīh ud rāyēnīdārīh rasēnd. ud gmōwišn ī dēn burdārān muhr ud wizurd ī dādwar ī rāst gōwišn ī rāstān ud ānīz ahlawān hangēzišn be bawēd. gōwišn ī xwurdagān spazgān ud abārōnān ud afsōsgarān ud ān ī drō dādestānān rāst ud wābar dārēnd.Google Scholar

34 For the assertion that the image of leveling of mountains in Jewish sources is the result of Iranian influence, see, inter alia, Winston, David, “The Iranian Component in the Bible, Apocrypha, and Qumran: A Review of the Evidence,” History of Religions, 5:2 (1966), 191ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar For a similar assertion with regard to Christian use of the image, see Cumont, Franz, “La fin du monde selon les mages occidentaux,” Revue de l'histoire des religions, 103 (01–06 1931), 78, n.2.Google Scholar Finally, Bausani, Alessandro, Persia Religiosa (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1959), 143,Google Scholar followed by Duchesne-Guillemin, Jacques, La religion de l'Iran ancien (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1962), 359, argues for the Islamic use of the image deriving from Iran.Google Scholar

35 The image is extremely widespread in antiquity. To cite only a few instances, it occurs, in Jewish sources, in Isaiah 2:14 and 40:4, Ezekiel 38:20, Habakkuk 3:6, Job 9:5, Psalms 46:2–3, Assumption of Moses 10.4, Apocalypse of Baruch 5.7, Ethiopic Enoch 1.6, and Sibylline Oracles 3.777–79; among Christian sources in First Corinthians 13:2, Revelation 16:20, Sibylline Oracles 8.236, and Lactantius, De ave Phoenice 5–6; among Islamic, in Qur'ān, Sūra 18.47, 20.105–8, 56.5–6, 69.14, 73.14, 78.20, 8.13; and among classical authors, in Asclepius 25, Eustatius, Ad Iliad 16, and Seneca, Consolatio Marcus 26.6. For the most part, no specific significance can be posited for the use of this image in any of these sources, it being simply a stereotyped and rather bland image of catastrophe. One also notes with interest its occurrence within certain Melanesian cargo cults, for which see Worsley, Peter, The Trumpet Shall Sound (New York: Schocken, 1968), 99, 154.Google Scholar

36 Revelation 6:12–17, Revised Standard Version.

37 See Qur'ān, Sūra 69.13–37. The mention of leveling occurs in verse 14, the passage quoted is verses 28–29. Verse 34 further specifies that the crime for which the evil–doer is being punished is his failure to encourage the feeding of the indigent. Translation from Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, ed. and trans., The Holy Qur–'an (New York: Hafner, 1946), 1600.Google Scholar

38 Qur'ān, Sūra 18.47–48; Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, The Holy Qur–'an, 743.Google Scholar

39 Translation from Hok-lam, Chan, “The White Lotus–Maitreya Doctrine and Popular Uprisings in Ming and Ch'ing China,” Sinologica, 10:4 (1969), 212ff.Google Scholar

40 See, e.g., Sukhāvatīyūha 17–18,Google Scholar describing the Pure Land of the Bodhisattva Amitabha. A convenient translation is available in Conze, Edward, ed., Buddhist Scriptures (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1959), 233–34.Google Scholar

41 Graham, A. C., trans., The Book of Lieh-tzii (London: John Murray, 1960), 102.Google Scholar

42 Scheiner, Irwin, “The Mindful Peasant: Sketches for a Study of Rebellion,” Journal of Asian Studies, 32:4 (1973), 587.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

43 In Cohn, Norman, The Pursuit of the Millennium, rev. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 321.Google Scholar

44 See Lincoln, Bruce, “Temporal Orientation and the Political Dimension of Myth,” in Die Schnsucht nachdem Ursprung: Kritische Aufsatze zur Mircea Eliade, Duerr, Hans-Peter, ed. (Frankfurt: Syndikat, forthcoming).Google Scholar

45 Thus, for instance, Eddy, , The King Is Dead; Harald Fuchs, Der geistige Widerstand gegen Rom in der antiken Welt (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1938);Google ScholarWidengren, Geo, “Quelques rapports entre juifs et iraniens à l'époque des Parthes,” Vetus Testamentum, Supplement 4 (1957), 197–241;Google ScholarFreedman, David Noel, “The Flowering of Apocalyptic,” Journal for Theology and the Church, 6 (1969), 166–74;Google Scholar or Collins, John J., The Apocalyptic Vision of the Book of Daniel (Missoula, Montana: Scholars' Press, 1977), 191–218, to name but a few examples.Google Scholar

46 See, most especially, Bickermann, Elias, Der Gott der Makkabder (Berlin: Schocken Verlag, 1937).Google Scholar

47 Cited in Hill, Christopher and Dell, Edmund, eds., The Good Old Cause: The English Revolution of 1640–1660, 2d ed. (London: Frank Cass, 1969), 331.Google Scholar

48 Cited in Worsley, , Trumpet Shall Sound, 154.Google Scholar

- 8

- Cited by