Exemplarity is almost always examined from a point of view taken from outside the exemplar itself. There are analyses of the advantages and disadvantages of exemplarity as a methodology (Jeanneret Reference Jeanneret1998; Goldhill Reference Goldhill2017), discussions of the roles and virtues held to be exemplary in a given socio-historical environment (Sheridan Reference Sheridan1968; Gayer and Therwath Reference Gayer and Therwath2010), and studies of the ways in which political regimes advance their purposes by the propagation of exemplars (Bulag Reference Bulag1999; Bilgrami Reference Bilgrami2003). There are investigations of how people search for, choose, relate to, and deal with exemplary figures present in their life-world (Humphrey Reference Humphrey and Howell1997; Kristjansson Reference Kristjansson2017; Robbins Reference Robbins, Laidlaw, Bodenhorn and Holbraad2018). Much less studied is the topic of this article: the situation of someone who himself or herself tries to live as an exemplar—or at least to carry out exemplary acts in person. In using the term “exemplar” here, my primary reference is to its main dictionary meaning as a person or thing considered to be so meritorious that they are worthy of imitation and emulation, rather than to its second usage to indicate a typical example of something that might be either good or bad. There are many people who desire to lead lives that are morally good in their own eyes and those of their immediate neighborhood. But to aspire to be an exemplar in the primary sense just mentioned a person also has to perform their own life as a model of certain virtues, addressing potential followers, whether these are close people, a wider public, a nation, or even “humanity itself.” Of course, exceptional people of this kind—and one could think of Augustine, Gandhi or Hitler—have been exhaustively studied as regards their ideas, historical roles, personalities, intellectual influence, and so forth, but the “first person” question of the self-structuring of oneself as a model for others has received relatively little attention. What does conducting oneself in such a way involve? And what are the conceptual frameworks we need in order to be able to begin to answer this question?

One may start by comparing the person who wishes to be exemplary with the more general case of the actor aiming to live an excellent human life. As Irene McMullin points out in her study of the latter, Existential Flourishing: A Phenomenology of the Virtues (Reference McMullin2019), living a good life is inevitably a relational matter. She writes that it is mistaken to see flourishing as either a private state of the subject or as an objective state of the person conceptualized as a thing in the world; for both of these positions “fail to see the dependence of the self on the world and others who share it and fail to accommodate the lived normative responsiveness that defines us in our attempt to live in the world well” (ibid.: 1). This point, I suggest, applies also to the exemplary person. McMullin argues that an account of human flourishing must involve three dimensions: that of first person experience (“I am at stake in my experiences”); that of the dialogue with the surrounding world and the normative values it provides, these being the third-person categories that legitimize the subject’s personal thoughts and feelings; and thirdly, the recognition of the immediate claims others make on us, which have their own second-person authority that binds us in our attempt to live well in the world. To live a good life requires us to respond well to these distinct moral terrains, and crucially, to negotiate the tensions that may arise between them (ibid.: 2–3). Accepting these suggestions for the time being, I would add that a framework for understanding the relational matrix of the exemplary subject requires something extra—the delineation of a peculiar meta-operation. This is the exemplary actor’s wielding of their own selection of the third-person societal values, refusing to be bound by the others, in order to create an idiosyncratic representation of the good—and not just a representation but a demonstration addressed to those second-person folk, whose own immediate everyday claims may well be ignored in the process.

Comparing action thought to be good, in one’s own and others’ eyes, and that intended to be exemplary involves, I suggest, a quite complex consideration of intentionality. Commonly, an act is judged praiseworthy if it is chosen against the non-meritorious option of refraining from it, or choosing some meaner alternative. Such a choice seems inevitably to involve the intention to do good, and in principle it applies to both simply morally good and exemplary acts. Yet in relation to the latter further thought is required in relation to the tripartite schema proposed by McMullin. For one thing, the relation of the “exemplar” to the second-person others who might admire the act and become “followers” is non-binding on both sides (unlike McMullin’s second-person claims). For the exemplary act to seem quintessentially good, the actor has to make it seem as though it is a free choice that is not compelled by family, friends, or a commander of some kind, and that it is its rightness alone that has motivated it. And then exemplarity does not imply second-person obedience. It requires rather that the responders choose to imitate, emulate, or defend it, interpreting the meaning of the act as they see fit and “reiterating” it in their own circumstances (Humphrey Reference Humphrey and Howell1997). Here we might make in principle a broad comparison between the ideal types of the exemplary actor and that of the political leader. The former aims to create a “following” with the same qualities s/he aspires to and envisages this as a voluntary rallying to the force of the ideas; whereas the leader does not wish followers to be like him/herself—indeed better if they do not have leadership qualities—and therefore such a leader often has to find means to make these relations non-voluntary and binding. However, in practice and especially in war situations, the same person may be both an exemplar and a leader, and as will be shown below this can bring about a “slippage” in the performance of exemplarity.

In certain situations, the exemplary act raises the question of a different structure of motivation, the inspiration of some High Being or inviolate source of morality, and this cannot be identified simply with McMullin’s third-person category “the world,” with its multifarious human moral pronouncements. In the case of religious exemplars (e.g., Augustine, Calvin) and also some politico-religious ones (e.g., Cromwell, Gandhi), the pronouncement that their exemplary acts have been inspired by, even bound by, some source of rightness outside themselves, by God, Providence, Atman, et cetera, the avowal that this inspiration as it were flows through them and that they themselves are not fully free but a channel is all to the good. Such a structure seems to lend the action a greater character of exemplarity. It serves to separate off the personally good (in the sense of intentionally chosen kindness, altruism, etc.) from the exemplary, which, stemming from a Higher Rightness, can be demonstrated to the multitude by someone who may not be a good person at all in other ways. In sum, self-realization as an exemplar skews the three competing claims identified by McMullin in certain characteristic ways.

However, this article will not address religious exemplars, but the case of a political one, and will discuss specifically the actions of someone widely, though mistakenly, identified with mid-twentieth-century fascism. Yet before I begin this analysis it is worth noting that in such a political case, the freedom of the exemplary actor to decide what it is that s/he puts forward as an admirable model is particularly problematic. The need for exemplarity in political life is very often brought into being by opposition and conflict—the need either to promote a new idea, some cause that is not the status quo, or conversely to defend a stance that is under attack. Both cases involve more than demonstration of a virtue in the abstract. As is recognized in virtue ethics and is a sine qua non in the anthropology of ethics, the meaning and motivation of individual acts cannot be understood in isolation from the social context in which those lives occur. The political exemplary act has to be rooted in some larger whole of the values associated with a particular way of life if it is to have any grip. Sometimes it may even appear to be determined by the exigencies such values imply, meaning that the exemplary actor was in some sense bound to act the way s/he did.

This point is discussed by the philosopher Bryan Smyth (Reference Smyth2018) in his paper “‘Ich kann nicht anders’:Footnote 1 Social Heroism as Non-Sacrificial Practical Necessity.” Smyth asks: how it is that, even in an entirely non-religious situation, someone who renounces all responsibility for his exemplary act, saying he did it out of necessity (“I cannot do otherwise”) may still nevertheless be admired as a hero? His answer is an anthropological one: if the agent is seen to inhabit a beloved shared ethical habitus, having the same embodied predisposition, and in deep continuity with this social environment—then that is seen as the causal circumstance of the act, which then can be appreciated as both spontaneous and ethically outstanding. The act is meritorious because it literally exemplifies certain socially held values.

All of this is by way of clearing the ground. The argument made here is that personal acts, if they are to work as exemplars, must indeed embody certain socially held values, and although “practical necessity” may indeed be a way they are described, they are nevertheless different from either heroism or sainthood. For the political exemplary actor in an arena of competing values could do something else. He or she puts forward an example of something, not something else that they could have done. In such an act, the chosen virtue does not simply happen to be noticed and appreciated by others, but has to the best of his ability to be made explicit by the actor to the envisaged shared constituency. From the actor’s position, especially in the maelstrom of competing visions of the good, this has to be done in order for his act to be distinctive, for it not to be misunderstood. However, as will be shown, and perhaps particularly in war situations, such a targeting is rarely entirely successful. Various kinds of slippage are almost inevitable. For one thing, actions are almost never only or purely exemplary, but are attended by all kinds of other exigencies and rationales as well, and for another, and partly because of the first point, even if an act is seen by the subject as an obvious example of X value, this does not mean that others—even close companions—will necessarily understand it that way.

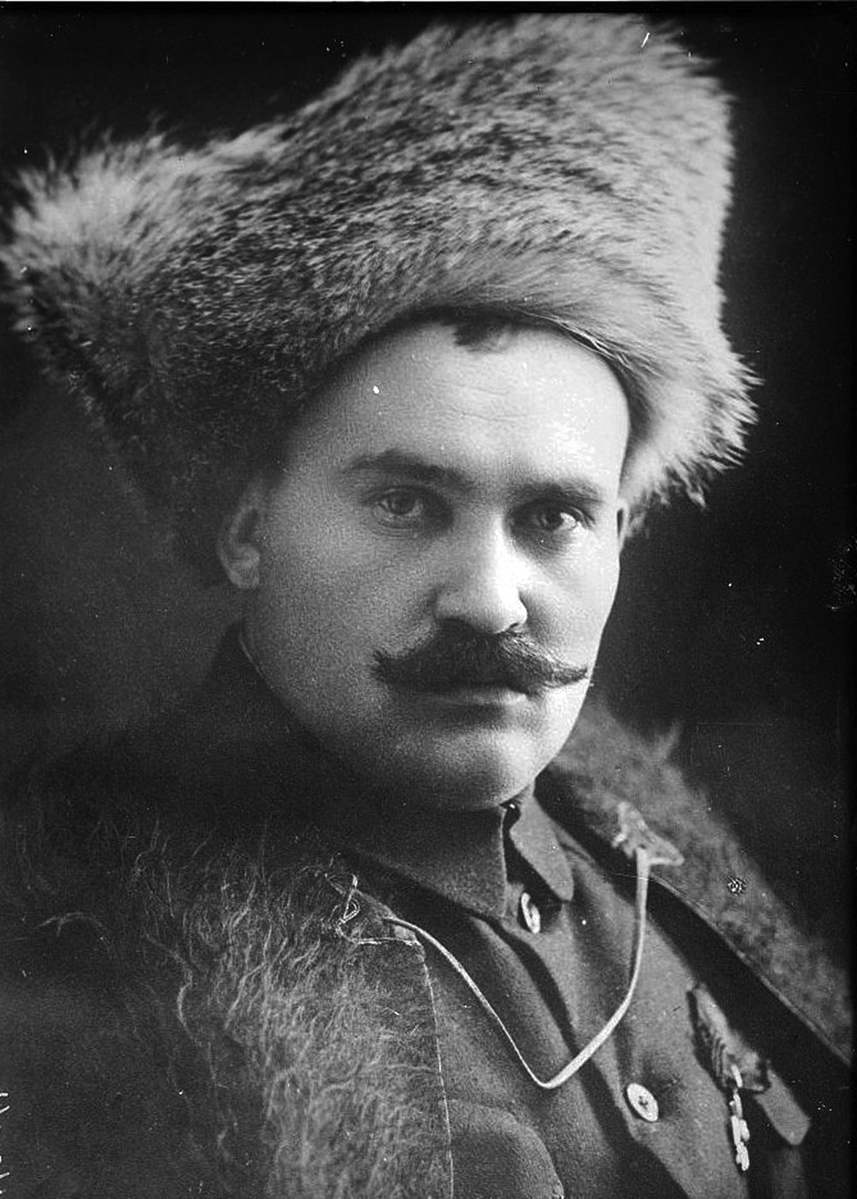

Figure 1. Captain Grigorii Mikhailovich Semenov as a young officer (date unknown). (Photograph: Wikimedia.)

“Ataman Semenov” in the Eyes of Others

To examine these issues, I propose to discuss the case of Grigorii Mikhailovich Semenov, a Cossack officer in Siberia who led one of the fiercest White armies fighting against the Bolsheviks. I made this choice partly because Semenov is widely regarded as wicked and cruel, the last person to be seen as exemplary. But this makes the case all the more interesting, and not only because people who set themselves up as exemplars are likely to be pulled down.

It is no surprise that Semenov’s enemies the Bolsheviks (the Reds) would call him “evil,” an ideological foe, and a traitorous collaborator with the Japanese interventionists. After he was driven out of Russia into exile in China in 1921, the Soviets continued to depict him as a vicious plotter with imperialists, a dangerous threat waiting to invade the sacred frontier of the USSR, a figure further darkened in the 1930s by accusations of fascism. But Western historians and political journalists also condemned Semenov, though in rather different terms, attacking his savagery, downplaying his military importance and mocking his pretensions. Even in serious works that later in the text complicate the initial picture, he is introduced to readers as “a strange and terrible man” (Fleming Reference Fleming1963: 47); “an infamous warlord” characterized by “sadism and avarice” (Bisher Reference Bisher2005: xvi); a “freebooting Cossack marauder” and a “bandit in the classic Hung hu tze tradition of Asia’s wild east” (Smele Reference Smele1996: 72). The very look of Semenov—his bushy fur hat, his imperial moustache with its snazzy twisted up ends, the combed peak of his forelock, the piercing glare with which he faced photographers—all seemed to place him as a being from another, premodern world. European writers readily painted in—in fact barely discernable—Asian features, and they reveled in supplying accounts of his “seraglio” of women. Yet such writers had to admit to a certain puzzlement: how was it that the repugnant Semenov had evidently seemed an admirable and compelling person to many diverse contemporaries? I cite one example of such an assessment:

With his ‘enormous head, the size of which is greatly enhanced by the flat Mongolian face, from which gleam two clear brilliant eyes that belong rather to an animal than to a man,’ his Napoleonic lock of hair and his cloudy pan-Mongolian aspirations, Semenov was an extraordinary figure, a sort of Heathcliff of the steppes. His deeds were odious, his motives base, his conduct insolently cynical; yet he somehow always managed to convey a good impression. In April 1918, before the full depths of his turpitude had revealed themselves, he struck an experienced British officer as ‘exceptionally patriotic and disinterested’; and nearly two years later the British High Commissioner in Siberia, Miles Lampson, while admitting that the harshest criticisms of Semenov’s regime were justified, believed the Ataman himself to be ‘personally sincere’ (Fleming Reference Fleming1963: 52).

I shall make the argument that Semenov was, and intended to be, an exemplary leader and that the splintered opinions he provoked were provoked in part due to the way such a person is bound to live. No one person can exemplify all human virtues, and I would argue that the exemplary actor cannot even manifest publicly the full plenitude of the moral values he himself recognizes, because these may be contradictory or mutually nullifying. Exemplarity has to prioritize sharply, and therefore to shelve certain kinds of merit that might obscure what the actor wants to be seen to be standing for. Semenov’s choice was resolutely military. In this, his stance was relational and socially embedded in the senses outlined by McMullin and Smyth: it was to exhibit by means of his own actions the unbridled martial normative values of the Siberian (Transbaikal) Cossacks and fling them in the face of the “empty Bolshevik promises” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 13). More broadly, we can see this representational throwing of the gauntlet as the manifestation, in demonstrative action, of a historical societal confrontation: that of the Old Regime, which had attempted to tame the Cossacks by giving them an honored place, against the new, rigidly applied Party rule, class struggle, and redistribution of property being enacted by the Bolsheviks. Semenov was unrelenting in his position, so, as will be described later, his stance also pitted him against the revolutionary half-measures of the Provisional government brought into power after the February revolution.

That Semenov saw himself as an exemplar is evidenced from diverse sources: his own writings, the observation of his contemporaries, and above all, by the eye-catching bravura of many of the actions he took. In exile in the late 1930s, he wrote an autobiography, entitled O Sebe [About myself]. One has to admit that this is not a book of psychological self-assessment; the relation of the writer to the self being depicted has to be divined from what is obscured, what highlighted, and what left out altogether. And in any case, a memoir written by an exemplar is likely to inhibit full disclosure. Fear, dread, and shame are absent. The “I” of the book appears as an initiator, a leader, a defender of actions taken, and a thinker, but not as a husband, father, or lover, all those personal aspects of his life being absent in the text. If I am not mistaken, not a single female appears in its pages. This autobiography is a description of events and an explanation of the author’s reasons for acting as he did, along with extensive musings on Russian political philosophy in the twentieth century. Its self-criticism is limited and mostly takes the form of admission of mistaken decisions, such as placing too much trust in certain subordinates. The book must concede Semenov’s inability to get his message through to the Siberian population as a whole (that having been swamped by naïve and deluded enthusiasm for the “bacilli” of Bolshevism: Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 13), and therefore he admits his failure to carry out the patriotic mission he had assigned himself. He could acknowledge that he had lost the battle to extirpate communism from Russia, but at least in these pages he was resolutely committed to upholding his own moral rightness and personal authority. The memoir should be understood, I think, like the autobiographies of Gandhi, Iqbal, and Nehru (Masjeed Reference Masjeed2007), as “performative,” a means of composing a life-story intended to work as an exemplar for the nation—in this case, the multiethnic Russian nation.

Another kind of evidence that Semenov was an exemplary figure is that he was taken to be one by his officers. He inspired deep devotion both during his life and for decades afterwards. For example, when Semenov was almost overwhelmed by Red forces in 1920, the stodgy General Kislitsin refused to escape with a breakaway detachment on the grounds that, “I did not think I could abandon the army of Ataman Semenov, counting it my duty to share the fate of the soldiers of our adored war-leader.”Footnote 2 After defeat in 1921, Semenov’s armies retreated to Manzhouli, the railway town just over the border in China and key to the Russian-controlled Chinese Eastern Railway (CER).Footnote 3 Some of his men later scattered to south China, Japan, Australia, and America. Further thousands of households from the Cossack communities that had supported him fled across the borders to Mongolia and to a nearby region known as “Three Rivers” (Trekhrech’ye) in China. In these several places, they continued to live according to Cossack and Orthodox Christian traditions. That they took the Ataman as the exemplar of this way of life can be seen in the fact that, despite the scattering in exile, they took his name as their identity. They were known to themselves and everyone around as “Semenovtsy.”

One hundred years later, their descendants are still called by this name. During the decades of Soviet and post-Soviet patriotic propaganda, the Semenovtsy had to lie low and their very existence became a matter of obscurity and rumor. Even now, for many Russians the term calls up an image of despised, defeated enemies, of downtrodden but still suspect, “closed” and alien-minded people (Peshkov Reference Peshkov2017). O Sebe was a forbidden text in the Soviet Union. When it was finally published in Russia in 1999, it created a sensation (Romanov Reference Romanov2013: 16). By this time, many historians were open to new configurations of what it meant to be a Russian patriot, and a process of reinterpretation of Kolchak, Semenov, Wrangel, and other White leaders cautiously began. It was not only that revelation of hitherto silenced sources made possible a questioning of the standard Soviet history of constant, morally unblemished victories of the Bolsheviks as they advanced through Siberia. The question began to be asked: had Semenov been wrongly condemned to death as a traitor in 1946 by the Soviets? A film was made. Australian Semenovtsy began to post videos of their meetings posed with a photograph of the Ataman.Footnote 4 More recently in Russia, however, the possibility of rehabilitation of Semenov has been damped down again; the topic is still too raw in historical memories (Ostapchuk Reference Ostapchuk2013).

Reconsideration of notorious, bloody events (Romanov Reference Romanov2013) suggested that almost always it was not the Ataman himself, but his subordinate (in fact, highly self-willed) officers who had carried out the slaughter. One of these was the fanatical mystic who issued edicts on his own account and later proclaimed himself ruler of Mongolia, Baron von Ungern Sternberg (Sunderland Reference Sunderland2014; Smith Reference Smith1979: 60; Pershin Reference Pershin1999: 194; Kuz’min Reference Kuz’min2004a); another was the equally unruly tyrant Ataman Kalmykov, who is said to have seen Semenov as a “father figure” and who for a time held sway in the Ussuri and Khabarovsk regions of the Russian Far East (Smith Reference Smith1979: 61–62, 66). Only rarely were these far-flung exploits under Semenov’s direct command, let alone his control, whatever he liked to claim if they worked out well. In general, the reputational question in such a pitiless civil war is difficult to solve, since it is certainly true that many brutalities were executed “under Semenov’s aegis” or in his name. In relation to the topic of this article, they reveal the non-binding character of exemplarity mentioned earlier: they were carried out by officers acting in what one might call “the spirit of Semenov.” There is a grammatical suffix in Russian (-shchina) that expresses this phenomenon, denoting the period or state of affairs associated with a political actor. The suffix very often carries a negative connotation, as in the well-known example “Yezhovshchina,” the purges carried out under Yezhov in 1936–1938, also known as the Great Purge. In the same vein, we have the expressions “Semenovshchina,” and “Atamanshchina” which were used by Soviet writers to refer to the brutal measures taken by several Cossack leaders in the anti-Bolshevik fighting (Smith Reference Smith1979). The word “Semenovshchina” negatively motivated in this way would naturally occur only on the lips of his opponents. Nevertheless, its existence indicates a vocabulary for the recurrent phenomenon of “over-execution,” of a collective state of excess enabled by the structure of the political exemplar, which provided a point of origin but no control over interpretation by recipients in diverse circumstances.

This article is not intended to be a fully-fledged analysis of Semenov, nor a justification of his violent acts. Its aim is to consider him as a provocation to thought with regard to the subjectivity of the exemplary person. However, because I argue that the moral values he sought to uphold were the relational currency of the particular Siberian Cossack social environment in which he grew up and later fought his battles, I have tried to include materials from local sources and not available in English, with less emphasis on rehearsing the geopolitical accounts found in the scholarly literature on the Civil War (e.g., Smele Reference Smele1996). I now provide one such a point of view by quoting at length, with comments, from a summary of Semenov’s life as recounted by Anatolii Kaigorodov, chosen because he was a writer from a family of devoted Semenovtsy from the Trekhrech’ye district in China.Footnote 5 This serves to provide a basic outline, and, being written by someone who took Semenov to be an exemplary figure, is also interesting because of its highlights, mistakes, and omissions. The subsequent section explains Semenov’s own view of Russia’s need for exemplary leadership, indicates the values he held dear, and recounts some key exploits by which he made his point. In the final section, before drawing some conclusions, I discuss his attitude to the international fascism of the 1930s and the path he advocated for Russia.

A Life of Semenov by a Devotee

The head of state power of the Russian East, General-Lieutenant, Ataman of the Transbaikal, Amur, and Ussuri Cossack armies, Grigorii Mikhailovich Semenov, was born in September of 1890 in Kuranzha village of the Durulgievskii post in the Transbaikal region in the family of an ordinary, not rich, hereditary Cossack. [Kuranzha is a sleepy settlement of wooden cottages in a sweeping steppe near the border with Mongolia. Nomadic Buryat herders lived nearby, and Semenov grew up speaking fluent Buryat Mongolian as well as Russian. He wrote in his memoir of his love for this landscape—CH.] In 1911, Semenov graduated with honours from the Orenburg Cossack College and from then onwards he was in military service. In the First World War on the Romanian front, Captain Semenov, commander of a company from the Nerchinsk Cossack regiment, was awarded the Georgiev Cross [the highest award in the Russian army for personal bravery—CH]. In 1917, he wrote to Kerensky, the Minister of War, suggesting he be allowed to form in Transbaikalia a separate Mongol-Buryat Cossack cavalry regiment and lead it to the Russian front-line formations with the right to punish deserters. [At this point, the Russians were still fighting the Germans, but their army was disintegrating under waves of desertions—CH.]

Soon the Nerchinsk regiment was called to St Petersburg to guard the Provisional Government. Semenov found himself under Colonel Muraviev, who was in charge of organizing army recruitment. Being stationed in the headquarters, Semenov became convinced that the Sovdep [Soviet of Deputies—CH] was made up almost entirely of deserters and criminals freed by the revolution, and he advised Muraviev to “decapitate the system of disintegration and betrayal” that had been organized from abroad by the socialists. He suggested using the forces of two military academies and Cossack detachments to occupy the Tavricheskii Palace, arrest Lenin and the members of the Petrograd Soviet, and immediately shoot them. However, Muraviev relayed this plan to his seniors, who forbade Muraviev to take any such action and it was decided to order Semenov far away from the capital. On the 23rd June, he was received by Kerensky, and having received the mandate of the Commissar of the Provisional Government, he set off for Irkutsk to set up his volunteer Cossack troop.

Hardly had he started work when Semenov received news of the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd. Immediately, he set about organizing opposition to the rapid spread of Soviet power in Siberia and Transbaikalia. He instigated uprisings in the Cossack villages and barracks. However, most of the men, subjected to Bolshevik propaganda and tired of fighting, remained indifferent to Semenov’s call. In December, with a small troop loyal to him, he retreated to Manzhouli [the border town just inside China—CH].

Just before this, on the 22nd or 23rd November 1917, Semenov had a communication by telegraph with Lenin. The conversation was noted down by Semenov’s eldest son, Vyacheslav.

Lenin: “Rumours have reached me that you shot two of our comrades, members of the Bolshevik Party carrying out the orders of the Central Committee.… Is that true?”

Semenov: “No, it’s not true! We shot two provocateurs and terrorists, who were aiming to undermine the army discipline and prevent the troops from being sent to the front.”

Lenin: “You should be harshly punished. The gallows await you!”

In Manzhouli, Semenov formed the Special Manchurian Detachment (OMO), with which he crossed back over the border and began fighting in January 1918. However, defeated by the 1st Argun regiment under the Bolshevik S. Lazo, he was forced again to retreat across the border. Despite an attempt by the Chinese to disarm him, by April his army was filled with fresh Cossack recruits and he again launched an attack inside Russia. On the 20th August, he freed Verkhneudinsk and six days later the city of Chita [the two main cities of Transbaikalia—CH]. The Provisional Siberian Government then nominated Colonel Semenov as Commander of the Chita section of the army. In January 1919, the Supreme Ruler, Admiral Kolchak (with whom Semenov had earlier been in serious disagreement), named Semenov as the commander of the entire Chita military region. Soon Grigorii Mikhailovich was elected as the Ataman of the Transbaikal, Amur and Ussuri Cossack armies [which extended his sway to the Far East up to the Pacific Coast—CH]. In November, he attained the rank of General-Lieutenant.

In January 1920, in view of the desperate situation at various fronts, Kolchak assigned to Semenov full governing power over the whole of the Russian Eastern Regions, with his capital to be at Chita. After the tragic death of the admiral, on the 6th October 1920 Semenov sent the following telegram to General Wrangel:

I count it my duty not only to recognize You as the ruler of South Russia but also to subordinate myself to You, while remaining the ruler of the Russian Eastern Regions. In my own name and that of the army under me and that of the entire population, I greet You in your great service to the Fatherland. May God help You!

On the 22nd October after fierce fighting, Chita was taken by the Reds. Nearly a year later in September 1921 Semenov left Transbaikalia for ever. [Numerous other sources say Semenov left in October 1920 after the Bolsheviks took Chita, (Sunderland Reference Sunderland2014: 153)—CH.] In Manchuria, the Semenovtsy dispersed to the Cossack posts along the line of the Chinese Eastern Railway, and later, while many left for America and Europe, most settled in Harbin and Shanghai. Ataman Semenov became the leader of the Russian emigrés. […]

I have already written in my “Stanitsa”Footnote 6 about the two letters written by the Ataman to Hitler. Ever since the First World War Semenov had continued to regard Germany as the enemy, but nevertheless he was convinced that the Germans were a lesser evil than the Bolshevism of Stalin. Like General Vlasov, with whom he was in regular contact, Semenov thought, “A victory for Hitler will be a defeat for Stalin, not for the people!” And we should not forget here the terrible experience the Semenovtsy had had in “relations” with the Bolsheviks—from the partisans to the regular Red Army and the organs of the VChK-OGPU-NKVD. All across Siberia, the partisan ranks were filled, with few exceptions and often by force, with various rabble—urban and village low life, freed prisoners and drunkards. For these people killing and theft were their normal way of life. And then there was the terrible directive of 24th January 1919 ordering ‘pitiless mass terror against the Cossacks,’ which was handed over to bandits to carry out in full. Oh, how many stories did I hear in Manchuria from refugees about the truly monstrous things that happened in those days in Transbaikalia! (Kaigorodov Reference Kaigorodov1999).

The most notable silences in this account concern the wrongs of which Semenov is accused, notably his ordering of mass killings; his intentional disruption of Kolchak’s war effort; his reliance on Japan throughout; his theft of the Tsarist gold; and his extravagance and debauchery.Footnote 7 Kaigorodov refers only indirectly to the possibility of Semenov’s brutality by invoking an excuse, his supporters’ experience of the savagery of the Reds. What he does emphasize positively is a completely different set of specifically military qualities: Semenov’s personal bravery recognized by the top medal of the Tsarist army; his bold initiative in proposing the killing of Lenin; his defiance in the conversation with Lenin; his observation of legitimate political seniorityFootnote 8 (e.g., in his telegram to Wrangel); and his rise in military ranks, and his independent election as Cossack leader. Each of these is also highlighted, with many other examples, in Semenov’s autobiography.

Later in his piece Kaigorodov also gives a fateful exemplary glamour to Semenov’s acts in his last days as a free man in 1945. Having described the brutal mass invasion of Manchuria by the Red Army at the end of the Second World War when Japan was on the verge of defeat, Kaigorodov takes care to mention that Semenov refused an offer from the Japanese to flee to safety in south Korea in a ship specially ordered for him. The Ataman said he wanted to share the fate of the Cossack soldiers he had led into Manchuria. This is Kaigorodov’s account of Semenov’s arrest by the Soviets:

I now recap the story told me by a Russian woman in Dal’nyi [the south Manchurian port called Dalian by the Chinese, Dairen by the Japanese, and Dal’nyi by the Russians, where Semenov was then living—CH] in 1951, which coincided almost to the last detail with an account I heard in Kazakhstan in 1955 from a lieutenant who had been a witness of the arrest.

On that day, 15th August 1945, Soviet echelons were entering Dal’nyi by train and Semenov literally went out to meet his death. The lieutenant told me, “When our echelon was approaching the railway station, I looked out of the window and I saw on the platform a moustachioed man in a fine general’s uniform, wearing his medals and with his cavalry sword at his side. Our carriage stopped right opposite this gentleman, and when the doors opened some soldiers unceremoniously went up to him, including me and our platoon major, who was drunk and wearing an unbuttoned jacket and with his crumpled cap in his hand. The man with the jauntily upturned moustaches said loudly with a swagger for all to hear, ‘I am Semenov!’ The drunken major gasped and gave a hysterical cry, ‘You’re lying!’” This is exactly what the woman had told me, except that the major yelled, “Weapons!”

This event fulfilled the prophesy of the head of the Mongolian Lamaist church, the Bogdo Gegen Jebtsundamba Khutukhtu, who had said to the young captain Semenov in 1913, “You, Grisha, will not die a normal death. You will not be killed by a sword, spear or bullet. You will call up your own death.” In fact, the “Living Buddha” and Semenov were friends—the Ataman was fluent in Mongolian; he translated the Russian cavalry regulations into Mongolian and helped organize and teach three cavalry regiments which became the backbone of the Mongolian Army. Amazingly, though fighting throughout the First World War and the Civil War he was not even wounded once. Indeed, he did present himself into the hands of his executioners.

In this account, we can see Kaigorodov portraying Semenov as the essence of the model leader of the Transbaikal Cossacks: here is loyalty to his men, oneness with the cross-border Mongolian culture, refusal to retreat with alien allies, and bravura in the face of certain death. Semenov’s arrest may not have happened in the noble form depicted by Kaigorodov.Footnote 9 Still, what better proof could there be that Semenov was taken to be an exemplar than that these particular qualities were posthumously attributed to him by another generation? But the question we now need to ask is, what did all this mean in the politics of the time, and what, if this is what he himself intended to convey, did it mean to Semenov himself?

Acting as an Exemplar

Some key passages in his memoir where Semenov provides some answers to these questions occur quite early in his book. They are set out as the foundations, as it were, of his subsequent life. We are back in the early months of 1917, when the young captain was trying to persuade the Petrograd authorities to allow him to form his special Buryat-Mongolian Cossack brigade. To lose no time, he decided to go straight to the high military command rather than through the usual bureaucracy. He wrote to Kerensky, the Minister of War, arguing that the “nomads of East Siberia would form a natural irregular cavalry, using as foundation the historical principles of cavalry warfare from the time of Chinggis Khan, reformulated to conform with the improvements of contemporary techniques. […] Such a formation could serve as an exemplar (obrazets) for the reorganization of the Russian army” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 80, my emphasis). This was an amazing suggestion. Not only had the army never included Siberian “natives” (inorodtsy) in its fighting ranks, but Chinggis Khan was hardly a historical figure to arouse enthusiasm in Russian military circles. That it was approved in Petrograd may have had something to do with the thought that such a task would keep the importunate captain busy far away from the capital. However, there is more to it than that, for the Russian army had by this time in fact practically disintegrated. The Petrograd Soviet’s Order No 1, issued immediately after the February Revolution, instructed soldiers and sailors to obey their commanders only if their orders did not contradict the decrees of the Soviet. The result was widespread disobedience, and “a Bacchanalia of propaganda against the officers” (ibid.: 77). Semenov devotes pages to his despair at the endless soldiers’ meetings and councils that took the place of fighting in the war against the Germans.

In a panic, the Provisional Government had also ordered that it would be appropriate for the vast multinational country to set up fresh new armies on ethnic principles. But then, thinking that these might turn upon one another, compete for resources, and bring about yet further chaos, they abruptly withdrew the order. Semenov argued to Kerensky that it was a mistake to withdraw this order. He wrote that interethnic conflict would only occur if these armies of Tatars, Moldovans, and so forth were kept in the deep rear, where they would work for a comfortable life and advantages for their own nationality. If they were sent to the front, on the other hand, such a command would discourage cowardly nationalists from declaring themselves “natives” (inorodtsy), while the brave would gladly go into battle to fight not for their nation, but for the sake of Russia (ibid.: 80–81).

It was this argument, according to Semenov, that persuaded the Minister to allow him to go ahead. His brigade of Mongol Buryat volunteers, he wrote, would “set a moral example of bearing service on the line, and act on the psyche of those who were still war-capable in the army sections that had not yet fallen apart” (ibid.: 74). The essential qualities needed by the leader of such a brigade were the Cossack military virtues: boldness, decisiveness, readiness to sacrifice one’s life, capacity to deal with the unexpected, and acceptance of responsibility. And one virtue above all was demanded by war, the capacity for vnezapnost’ [suddenness, surprise, unexpected bold action]. “There is nothing new about this,” he wrote. “We only have to remember these truths and not forget to bring them into practice” (ibid.: 44).

I will shortly describe how he did bring such ideas into practice, but first—to recall Bryan Smyth’s argument (2018) about the need for the hero to share an ethical habitus in deep continuity with his social environment—it is necessary to provide more information about the Transbaikal Cossacks. Having explored, rampaged, and expropriated their way to the Pacific in the seventeenth century, the Siberian Cossacks in agreement with the Tsar were formed into a semi-autonomous border force to guard the frontier with China in the eighteenth century. There were not enough Russians to man the thousands of miles of the border, and indigenous inhabitants, whole clans of Buryats and Tungus, were recruited. Along the length of Eurasian borders, the Cossacks created their own distinctive “frontier culture” (Malikov Reference Malikov2011); this was patriarchal in a rough and ready way, above all defiantly independent, and regularly shocked mainstream society with its sexual freedom, strong-willed women, religious multiplicity and laxity, and tendency to take up “uncivilized” native habits (O’Rourke Reference O’Rourke2011: 158–63; Malikov Reference Malikov2011: 57–66). The Cossacks were a privileged estate (soslovie) in the imperial social order. They were allotted the best lands along the border, where their villages were attached to military settlements (stanitsa) that formed the bases of an extensive self-governing hierarchy with elected leaders (ataman). The men were required to fight on distant fronts when Russia was at war, and they had to provide their own horses, ammunition, equipment, and uniforms, but otherwise, they lived a privileged existence, untaxed, free from petty bureaucracy, able to trade. Famously, the Cossacks were “democratic”—in Russian parlance meaning self-government, elected leadership, and camaraderie between officers and men. In Siberia, they were far more prosperous than the neighboring non-Cossack Russian peasants and Buryat herders. Locally there was little communication between the Russian settlers and the indigenous peoples and a good deal of enmity when native lands were taken over by incomers. But the Cossack organization overrode this separation (many Buryat troops had Russian officers) and most Cossack families had some trace of the other in their ancestry. This brought about the emergence of a new identity, “Guran,” a people of mixed origins tending to be socially shunned by non-Cossack Russians and Buryats—to which both Semenov and Kaigorodov belonged.Footnote 10

Returning to the sandy streets, pine trees, and horse-dropping-littered squares of his beloved Chita, Semenov was to find that the Provisional Government had abolished the estate system and the Transbaikal Cossacks were dividing into two camps. Those who had remained behind in the stanitsas during the war had been “infected by revolution,” including observance of the dire Order No 1, but the returning “frontoviki” like himself were staunch defenders of their “immemorial rights.” “Our ancestors paid in the blood of their uprisings against the state for their right to autonomy and self-rule,” Semenov was to write (2002: 94). His defense of the Cossack estate had a caste-like or even Darwinian logic. The appeal he sent to the local government stated:

The formation of the Cossacks is explained by the process of historical selection of the bravest and most freedom-loving people, who, not wishing to subordinate themselves to the expanding influence of Muscovite statehood, gave up their homes and went away into wild lands to seek a free life. Pressing the local nomads ahead of them, the Cossacks paid with their blood to take charge of the new lands; and later, gradually mixing with the local inhabitants, subordinated them to their influence. Thus, Cossack landholdings were formed in a natural way and the Cossacks owed their acquisitions to themselves alone (ibid.: 94).

This appeal was unsuccessful. The disbanding of the Cossacks unleashed many savage local enmities and attacks, often by poor Russian settlers seeking to appropriate Buryat Cossack (and non-Cossack) pastures. But the Cossacks as a distinct people and identity still existed. Here we see the outlines of the social world to which Semenov was to appeal. We should not forget that he was still a young man, one of the despised Guran, and merely a captain in the military hierarchy. In the region, there were other more senior Cossack leaders, detachments of the regular Tsarist army, and bands of revolutionary partisans, not to speak of diverse advancing invaders: the well-organized Red Army, thousands of Czech prisoners of war, and the Japanese troops from the east, with American, French, and British interventionists soon to appear in the offing at Vladivostok. Amidst all this, Semenov’s model OMO detachment could only recruit from small and particular parts of the population. Apart from wild-card adventurers, these were the diehard loyalist Cossacks from along the border—who were now on the defensive in the face not only of Petrograd’s attempt to abolish their estate, but also against local attacks from people after their land.

When Semenov had to flee over the border from Transbaikalia to Manzhouli in late 1917, the Chinese authorities aimed to disarm him. This did not happen. In a remarkably short period of time his army filled with recruits and he was able to invade Russia again in the spring. How did this miracle happen? I cite the following incidents as exemplary acts aimed not only to win but also calculated to make an impression throughout the region and establish Semenov as a charismatic attractor for wavering Cossacks.

The first concerns his escape from Russia. Up to this point, Semenov had couched his plan to form a brigade as “revolutionary” as this was the language of the day and in any case his letter of authority from Petrograd was from the Provisional Government Sovdep. Now, however, he acknowledged to himself that his goal was anti-revolutionary (ibid.: 105). He paid a couple of followers to be spies, and from one of them he learned that the head of the local Sovdep was in touch with Irkutsk and Petrograd and plotting to take “decisive measures” against him. These measures were to be decided at a plenary meeting of the Sovdep late that very evening. Semenov also discovered that the officers of a local division of Cossacks were to be invited to the meeting and requested to execute the measures. Immediately he invited these officers to a lavish dinner. He arranged for one of his spies to telephone during the meal to say that the Sovdep meeting had unfortunately been called off and would happen another day. “I then suggested that we should finish the evening together in some place of entertainment, and we all went out into the street. We went past the building in which the meeting was happening, and suddenly, as if remembering an appointment, I told the officers I had to drop in to the Sovdep headquarters for a moment and would catch up with them in the bar later.” With one armed accomplice, Semenov strode into the hall, loudly declared the meeting closed and everyone present arrested. The accomplice then announced that the Cossack officers had not come to the meeting because they objected to the intrigues against Semenov. One of the Sovdep officials tried to remonstrate. Semenov silenced him by telling everyone to sit in their places, drop all weapons, and not attempt to leave the hall, since his own Cossacks were standing at the doors ready to shoot. “This had the desired effect,” Semenov continues. He promised that the meeting would be resumed in two days’ time with his own participation. Ordering his accomplice to get a troika ready for a fast escape before all these people could discover the truth, he made his exit. He had just enough time to reach the railway and catch the next express to Manzhouli (ibid.: 106–7).

Semenov had now burned his boats with the infuriated Sovdep as well as the Bolsheviks. But not with the Cossacks. He had demonstrated the admirable qualities of standing up for himself, daring, decisiveness, and above all “suddenness.” However, this adventure was as nothing compared to the next exploit noted in his memoir.

When Semenov arrived in Manzhouli he went to show his documents at the Chinese passport office (ibid.: 115; somehow, one is surprised at these mundane details at such a time of turmoil). The two Russian border officials were friendly and told Semenov about everything that was happening. There was full disarray in the large Russian army guarding the CER, there was much Bolshevik propaganda among these soldiers and also among the people of the town, and a Chinese army was waiting nearby for reinforcements before they moved in to oust the Russians from all control. There and then, Semenov decided to take charge of the situation. He invited the Chinese military brass to the passport office, suggested that it would be best if his own soldiers disarmed the Russian guards since this would avoid a fight between Chinese and Russians, and he then would take upon himself the task of keeping order. The Chinese General Gan agreed. Semenov then set to work to organize a plan aimed at disarming the whole garrison, in fact the entire town, and grabbing its huge stash of weapons.

He ordered a train with thirty heated carriages to be sent to Dauria, a military base on the Russian side of the border, to return “bringing in my troops, which should arrive by dawn on the 19th.” But, as his memoir states, Semenov had no troops: at this point he had exactly seven men under his command. He sent a message to the Barga Mongol Prince Gui-fu and to his wayward subordinate Baron Ungern, asking them to gather whatever men they could and to put it about that a large armed echelon was on its way from Dauria. He reckoned his plan was achievable with seven men. At dawn, the empty train arrived, and Semenov put two Cossacks to guard the closed carriages, instructing them to tell any enquirers that they were occupied by the Mongol-Buryat regiment. Meanwhile Semenov and Ungern, threatening an attack by the newly arrived troops, ordered each section of the Russian forces to lay down their arms, saying they would now be free to go home to their families. In an hour or two, everything was accomplished: crowds of disarmed soldiers were herded onto the empty train waiting to take them back to Russia. The arms store was seized. A couple of Semenov’s men arrested the Bolshevik Sovdep members in the town. They and the officers were packed into a sealed carriage. Semenov enjoyed the moment, telling them they should be proud to travel to Russia in a sealed train, just as their leader Lenin had done. Far and wide, he comments, there was amazement and admiration that seven Cossacks had been able to disarm a garrison of 1,500 (ibid.: 118–21).

This kind of exemplary subject exerts his magnetism primarily by means of indicative actions and these two incidents can be seen as such. Both of them make clear Semenov’s capacity for “suddenness” and outrageous impression management—which one might alternatively call deception. Of course, as related in the memoir these episodes were extracted through the lens of his memory and crafted to convey an effect on readers, so they are not realistic descriptions. For the latter, one would have to turn to other sources, such as Romanov’s monograph on Semenov’s OMO (2013: 38–39), which states that the seven men were in fact aided by the Chinese army. Still, his capacity for quick thinking in a fundamentally extremely precarious situation has to be acknowledged. At this time, as can be seen from photographs, Semenov was existing in dire circumstances. His “head-quarters” was a snow-bound single-story log house with cooking done in a large vat outside, and he lived at least for some period in a Mongolian yurt (Kuz’min Reference Kuz’min2004b: 336).

According to Romanov, an even bigger sensation in Siberia than the disarming was created by the arrest of the Sovdep committee members, for this gave rise to rumors of the brutal violence of the Semenovtsy which were then used to discredit Semenov. And this is the problem of exemplary action: in the minds of the ill-disposed, the act can lead to quite different conclusions than those intended. With time the rumors ballooned and took on the status of the official (Soviet) version of the incident, telling of mutilated bodies loaded onto the sealed train. In fact, the officials were not killed, arrived safely, and held a press conference when they got back to Chita (Romanov Reference Romanov2013: 39–40).

Around this time there took place another “exemplary action,” which I cite because it relates to Semenov’s own attitude to his own violence. His account is as follows. In early December 1917, he received a telegram from Von Arnold, the Russian governor of Harbin, asking him to arrest the Bolshevik Arkus, who had just been appointed to take charge of the Russian troops guarding the CER. Semenov boarded the train on which Arkus was arriving and arrested him, aiming to detain him for a few weeks to prevent him taking up the post. But Arkus, from the moment of his arrest, “began to behave in an extremely disgraceful way. He began to swear, using unforgivable words, at me personally and all the officers, he threatened revenge on the bureaucrats that had sanctioned his arrest, and then tried to address a fiery speech to the mass of soldiers on the platform. All this led me to call for a military court-martial right there, which condemned Arkus to death” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 115). Arkus was stabbed and shot on the spot.Footnote 11 This being the only recognition by Semenov that he had ever personally been responsible for someone’s death, the Arkus incident became the subject of a special publication (Barinov Reference Barinov2019). In it, the author asks the key (unanswerable) question: did the Ataman single out this execution in his autobiography because it was in fact the only one ordered directly by Semenov, the countless other deaths being the responsibility of other people in his group, or was it because this death was exemplary, in the sense that it stood for all the others?

Whatever the answer to this question, it is undoubtedly true that Semenov, having espoused willful and insubordinate Cossack daring in his own actions, could not deny this same quality to his followers. Acting as an exemplar thus stymied his effectiveness as a leader, his ability to exert control. In May 1919, he had to issue an apology for his officers’ undisciplined cruelties; “as a penalty for recent outrages and illegal acts … against the peaceful population he even restricted the Asiatic Horse Division to its barracks” (Bisher Reference Bisher2005: 176; Romanov Reference Romanov2013: 262–87). But ruthlessness in achieving victory was part of the Cossack story too. In his autobiography, Semenov was to write of Ungern (and in this context of himself too) that “he used many methods that are usually condemned and would be impossible in normal conditions. But it is necessary to remember that the abnormality of the situation we were in sometimes demanded extraordinary measures. And all the strangeness of the Baron always had at root its own deep psychological meaning as well as a striving for truth and justice” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 140). This is the view “from inside” of a person who ordered massacres, someone whose overriding goals relegated other virtues (“…in the conditions of civil war, all softheartedness and humanity should be thrown out in the interests of the common matter” (ibid.: 141).

An Unlikely Case of Postcolonial Subjectivity?

The expression “postcolonial subjectivity” is anachronistic for the language of the period and Semenov would not have thought of himself in such terms. But it is apt as an analytical lens in this case. The Tsarist Empire was an avowedly colonizing state. By the early twentieth century not just Cossacks but wave upon wave of Russian peasants and traders had settled in formerly native areas. But in the ruins of empires—the Ottoman, the Chinese, and the Russian—journalists, poets, and radicals had been traveling and corresponding across the continents exchanging ideas of an Asian renaissance. A powerful impetus was Japan’s defeat of Russia 1905. As Sun Yat-sen admiringly claimed, this had infused Asian people with a new hope of shaking off the European yoke of restriction and domination (Mishra Reference Mishra2012: 7). As a person of mixed Russian-Buryat heritage in Siberia, Semenov’s position was multiply ambiguous and changed during his lifetime. He moved from a straightforward aspirational identification with Tsarist Russia in his youth, for which his upbringing, first language, religion, and culture had prepared him, through homage to the independence and moral qualities of the hybrid Trans-Baikal Cossacks, and from there quite quickly also to a deep appreciation of Asian cultures and aspirations, in particular the Mongolian and the Japanese. He became, in fact, a cosmopolitan repository of different viewpoints. The future of multi-national Russia never ceased to be his overriding concern. In his writing, he maintained a high-Russian, educated, somewhat portentous voice. But virtually the only personal vignette in his memoir was a humiliating incident he evidently could not forget. As a young man, he visited Moscow for the first time with some Buryat fellow officers. In the Kremlin, some other visitors, a lady and her husband addressed them curiously, taking them for Japanese dressed in Russian uniforms. Semenov tried to explain they were Cossack officers, but the lady said kindly that she had nothing against them, though they might well be foreign spies, but they should not try to hide the truth. Ordinary soldiers might be natives, but officers must be Russian (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 30).

“Semenov,” the public image of the man, was undoubtedly subject to racist denigration by Europeans. Even when he was the only effective force resisting the Bolsheviks, even when President Woodrow Wilson was asking “whether there is any legitimate way in which we can assist Semenov” (Fleming Reference Fleming1963: 64–65), and when he became briefly the legitimate ruler of the eastern half of the country, there were always powerful voices that would not accord respect to such a man. In particular, his power and independence were denied by the epithet “Japanese puppet.” It is true that the Provisional Government and the British stopped funding Semenov from around 1918 and that he was thereafter greatly dependent on Japanese support in the form of arms, money, and advisers. It is also the case that the withdrawal of Japanese armies from Transbaikalia in 1920 left Semenov facing defeat and a forced to retreat to China. But this does not make it untrue that he had much freedom of maneuver. In 1918, gathering a group of Buryat and Inner Mongolian activists and intellectuals around him, he proposed an astonishingly ambitious plan: to expand independent Transbaikal into a vast pan-Mongolian state (Atwood Reference Atwood2002: 136). This venture flowered briefly, but soon collapsed.Footnote 12 Earlier he was active in reconciling the Inner Mongolian Khorchin with the Outer Mongolian Barga Mongols, recruiting hundreds of each into different sections of his army (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 131–33; Sablin Reference Sablin2016: 95–96). It was Semenov himself who formed an important link between the hitherto separated Buryats, Bargas, Kharchin, Khorchin, and Daurs. Furthermore, “puppet” ill describes the genuine warmth he felt towards Major Kuroki, the advisor and adjunct assigned to him by the Japanese,Footnote 13 who remained close to him for decades (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 135–36, 184). He also made a friend of Prince El-Kadiri of Egypt, whom he freed from captivity; for a time, El-Kadiri joined Semenov’s volunteer army, refusing the Ataman’s offer to send him to freedom via the British Consul in Peking on the grounds that he owed him a debt. Semenov commented, “The Prince now has a high position in his own land. We have not lost touch. I admire his purely oriental faithfulness to his debt” (ibid.: 111).

Semenov gathered the talents of many nationalities. In the turmoil of fighting across northeast Asia and diverse groups of prisoners of war attempting to cross Siberia to return home, his armies included Kharchin and Barga Mongols, Serbs, Romanians, Jews, Japanese, Koreans, Chinese, and others. But chief among them were South and Eastern Buryats, Tungus, and Khamnigan, all of whom would have been categorized as inorodtsy. As one recent commentator has written, perhaps what Semenov was doing was to demonstrate the inorodtsy fighting bravely as a pointed reproach to Russia (Yan Reference Yan2013). Following the failure of the Pan-Mongol attempt (see note 15), Semenov was in fact to switch the “Great Asia” dream he shared with Kuroki into a Russia-focused patriotic vision, wherein it would be qualities of Asian-Native-Cossack armies that would save the motherland.

Semenov was an admirer of the archetypal Mongolian skill, horse-riding, and he was a warm advocate of the flexibility of cavalry in modern warfare (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 47–52). But more important was the moral example he believed would be shown by his Mongol units (ibid.: 74). This conviction was linked to his own unusually open religiosity, which incorporated awe for Buddhist spirituality. Early in his autobiography Semenov recounts the eventful time he spent in Mongolia in 1911–1912 as a youthful captain. He does not mention the prophesy described by Kaigorodov, which may well be a legend, but he does recall other prophesies made to him by a different high lama, the Choijin Gegen, who was the official state oracle. According to Semenov, the Gegen foresaw the World War, the fall of the Tsar, and the Civil War (ibid.: 22–23). Semenov believed in the ability of certain rare spiritually gifted people to see what ordinary mortals could not and foretell the future. Referring to his own lesser powers, he wrote that the spiritual foreseeing of things to come had nothing in common with the intuition of the political leader, who having studied a tactical situation carefully with regard to his own competence, can give a correct prognosis of the immediate future (ibid.: 22). In this respect Semenov was unlike the mystic Baron Ungern, who never regarded himself as an ordinary mortal and adopted the notion that he was himself a Buddhist reincarnation.Footnote 14 In comparison, Semenov was a realist about himself—and about his Mongol troops. He admired their humane religion (Buddhism), their purity, honesty, hardiness, and daring, but wrote that as soldiers you have to use them right away: if they are subjected to hindrances and delay, they easily lose interest and give up (ibid.: 23).

Turning to Semenov’s significant interpersonal relations, one could say that his domestic arrangements also provided opportunities for exhibiting Cossack bravura, being both shockingly cosmopolitan in the eyes of respectable Russian military society and “non-binding” (to return to McMullin’s second-person category). In 1918–1920, rich with Japanese money, proceeds from nearby gold fields, and taxes and duties that should have been transmitted to Kolchak in Omsk, he enjoyed himself as the ruler of Chita. His inner circle included several beautiful mistresses as well as Major Kuroki, fellow Cossack officers, fleeing aristocrats, and occasional Western journalists and Allied officers. His domain extended into China, where he associated with Manchurian high society, gold traders, generals, and local bons vivants. Moving frequently, doing business, making inspections, visiting his troops, he kept a special train with an airy decorated “summer car” in which parties took place (Bisher Reference Bisher2005: 192). Semenov’s first wife Zinaida, who bore him two children, was kept away from the fighting, off the scene in Verkhneudinsk. Meanwhile, his favorite mistress was Masha Sharaban, a beautiful cabaret artist. Though usually called a “gypsy,” she was Jewish, the widow of a local Russian merchant. She was warm-hearted, ostentatious, recklessly extravagant, and often drunk. At dinners, she loved to sing songs in Yiddish. Semenov paraded this relationship; his magnificent 40,000 rouble “betrothal lunch” for her, given in late 1918, was the talk of Chita (ibid.: 136).

Given the virulent anti-Semitism prevalent in Russia’s Orthodox middle and lower classes, such an event can be seen as an “exemplary act”—a demonstration of Cossack impenitent sexual attitudes as well as Semenov’s sympathetic approach to the Jews. This was a community that was prominent, though always vulnerable, in the city’s life. For decades, Chita and other southeast Siberian towns had been the unsafe sanctuaries of Jewish exiles (writers, revolutionaries, artists) and Jewish merchants. Now, Semenov’s government issued an order forbidding pogroms against Jews. Throughout his reign “Yiddish drama continued to enliven one of Chita’s two theatres and Friday prayers echoed from the old synagogue” (ibid.: 136; Sunderland Reference Sunderland2014: 152, 280). This stance grated with a large majority of the White Russians, including those who had fled in exile to Harbin. Later, it was among these people that the Russian Fascist Party was to flourish (Hohler Reference Hohler2013). Semenov’s pro-Jewish and pro-minority sympathies alienated him from them.

In Japanese-ruled Manchukuo in the 1930s, Semenov had contacts with the Russian fascists, as he was generally held to be the leader of the White Russians in exile. He did not, however, join the fascist party. He did not believe that fascism was a single coherent ideology. It was not for export, he held, but a national affair. The fascism that worked in Italy would not do for Germany, and neither of them was right for Russia, that great multi-national state with its own traditions of government. So, although Semenov wrote two letters to Hitler in the 1930s to congratulate him on his success in gaining power, he was far from supporting the idea of transporting that model elsewhere. “I am not against dictatorship at certain decisive moments in a nation’s life,” he wrote, “but how would it be better to replace Tsarist autocracy by the arbitrariness of a bunch of foreign self-promoted adventurists presenting themselves as the core of a ruling party?” (2002: 343). What Semenov really objected to was the political party—any political party. For parties, he wrote, are inevitably self-interested and therefore socially and politically divisive. He believed that each separate citizen of any ethnicity, loyal to their country, had it within their ability to bring benefit to their homeland by their own actions. Understanding this individual duty to the country should stand higher than any idea of the good of the party (ibid.: 343–34, 350). Semenov conceived “Russian democracy” in this broad way and continued to advocate it from abroad, including by a number of abortive attempts and unlikely schemes through the 1920s and 1930s (see Boyd Reference Boyd2011: 98, 129–30). But by this time, what he stood for as an exemplar—and that was not democracy in any usual sense of the word—appealed only to a few scattered remnants, and his broader public image had long ago slipped from his grasp.

Conclusion

This article has argued, against the dominant narrative of plain immoral brutality, that Ataman Semenov is better understood as a would-be exemplar of Cossack military virtues. These he first attempted to demonstrate in life—by means of spectacular incidents in which “impression management” was crucial—and later through the selective explanations given in his autobiography. My intention has been to use the case of Semenov to clarify the nature of exemplary subject-hood and the traps it entails in a situation of political conflict. It involves the necessity of choosing to exemplify certain merits and not others, given that the exemplar has to represent a definite idea relevant to a particular kind of situation. Semenov took the Bolsheviks to be usurpers of power and he brought to the Civil War the particular qualities of Cossack intransigence and willfulness. He performed audacity, bravery, ruthlessness, and the ability to swerve so as to demonstrate these qualities to others. The trap here was that the very same unruliness would be enacted by his followers. Absent from Semenov’s repertoire were qualities such as modesty, scrupulousness, forbearance, or gentleness.Footnote 15 Acting as an exemplar involves an outwards projection of aspects of personality; but the second trap is that, since such a projection once performed becomes detached as a discursive element in the public sphere, it is always vulnerable to misinterpretations. The only social environment in which the actor could hope to be more or less certain of being understood is that of the common world of given values and a shared way of life. For Semenov, this was the border-dwelling Transbaikal Cossacks—but even for them, it has to be said, not in any simple way. For despite their military culture of identification with powerful chiefs (vozhd’) and their “exultation in the deed” (voskhishchenie postupkom), as one descendant described to me,Footnote 16 even the most loyal Cossacks would inevitably wonder how themselves to live up to the exemplar and whether some given action of their own would count as a true emulation (see discussion in Humphrey Reference Humphrey and Howell1997). This third trap of exemplarity, the self-doubt and hesitation of followers, Semenov often dealt with by the means of the imperious war leader plain and simple. He instilled fear and invoked “duty” not only in the voluntary sense but also in the premodern meaning (corvée, enforced service) still prevalent among the Mongols. In his memoir, he was later to acknowledge that the emphasis on duty had been a fatal flaw in winning over ordinary Cossacks: “we talked only of duties, while the Reds talked of peasants’ rights” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 257).

Does the attempt to analyze Semenov as an exemplary figure have any value to history and anthropology, as distinct from exploring the practice of exemplarity itself? In a perceptive review of publications on the Atamanshchina, Willard Sunderland (Reference Sunderland2008) raised two interesting questions that he felt required further thought. Criticizing the detailed but superficial account of Semenov given in Bisher’s White Terror (2005)—which was over-reliant on records of the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, that is, supplied by well-meaning but bewildered Yanks prone to a jaunty style and excited descriptions of senseless massacres, smoky dens of vice, cavalry dashes across howling spaces, and so forth—he asks whether deeper historical questions could be asked about the geographical, institutional and ethnic context and about terror itself as a particular kind of violence (Sunderland Reference Sunderland2008: 599). Was there, as Peter Holquist argued (Reference Holquist and Weiner2003), a “common conceptual matrix” that shaped the way violence was used by both sides in the Civil War? And in these Russian-Mongolian-Manchurian frontier lands might there have been a common Russo-Asian register of practices from which Semenov borrowed? Was the Ataman-style the same as the ways of the Chinese warlords of Manchuria or Xinjiang? (ibid.: 600).

Perhaps the investigation of exemplarity gives an opening into answering these questions, for it insists on delineation of which morals, virtues, or cultural norms are being exemplified. Semenov had many communications with “warlords” in Manchuria, such as Zhang Zuolin, and with Chinese generals and Mongol warrior leaders. In field tactics, he must have had some understanding with them. There was a culture of hardy masculine bravado across these borderlands. But this does not mean that Semenov shared the warlords’ political or social principles. The same response applies to Sunderland’s first question concerning a common conceptual matrix on all sides of the Civil War. While the various communist partisans (Russian, Chinese, Koreans) must have shared much, since they were in contact, and all adhered to broadly Marxist revolutionary ideas, and learned from one another, Semenov and the other Atamans had a completely different ideological and cultural register. Despite the common maelstrom of almost random slaughter, requisitioning, mutual vengeance, et cetera, there was still a difference. Compared with revolutionary puritanism, wily Japanese modernity, stiff-necked White Russian conservatism, and marauding bandits of the forests, the Atamans were sui generis. They, and in particular Semenov, the primus inter pares, were the only force to appeal to specifically Cossack traditions—which was even then seen as quixotic, since those ways belonged to a world that had been destroyed.

An example of this cultural specificity can be seen in the language Semenov used to appeal to the Cossacks of the Zorgol’skii stanitsa in 1919. A telegram to them began, “Children and brothers, we are all here as one, rising to support the fight against Bolshevism […] and we call on you children to go boldly against these scoundrels who are attempting to spread panic and rob our families.…” The telegram ended: “from your fathers, the Shmelins, Zhigalins, Baksheevs, Peshkovs […] and the whole stanitsa. Signed by hand for the Commander of the Army, General-Lieutenant Semenov” (Romanov Reference Romanov2013: 272). This intimate yet patriarchal style—the signatories being well-known Cossack families, not individuals—would have been unthinkable for any of the other of the protagonists in these borderlands.

There is a certain pathos, then, in Semenov’s summary of “Ross-ism,” his political philosophy for a future multinational Russia, an example of that relatively understudied genre of early twentieth-century political thinking: postcolonial yet not “progressive” (in a leftist sense). Even towards the end of his life, when he had traveled across the world, he could write: “Ross-ism, while defining the belonging of the sons of Russia, does not eliminate the racial and tribal differences between these peoples and accords them national-cultural and territorial autonomy, even if only on the principles of Cossack self-government that existed in pre-revolutionary Russia” (Semenov Reference Semenov2002: 351, my emphasis). He did not forget that vanished exemplary way of life, and nor did the Semenovtsy forget him. Their poems and songs are various, but often imbued with a sense of melancholy glory and lonely pride that seems to belong uniquely to this cultural-historical milieu.

A poem by a Russian Semenovets:

As for the Buryats, to this day elders hand down distant memories of target training and drills. Recruits to Semenov’s troops had to pin up their long Mongolian gowns so as to march with a high step, and they sang “Our Ataman”: