During the opening days of April 1955, a total of eighteen bombs exploded in various locations across Cyprus. The attacks were claimed by ‘Digenes’, soon to be revealed as Georgios Grivas, the leader of the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA). ‘Digenes’ was a nom de guerre that referred to Digenis Akritas, a famed Greek-Arab warrior of the Byzantine borderlands. At first, the attacks did not appear as a cause of great concern: one newspaper noted that explosions ‘slightly damaged the British Colonial Government Secretariat Building.’Footnote 1 As the days went on, a sense of unease crept into the reporting: ‘Police patrolled the main cities of Cyprus in strength tonight in an effort to prevent bomb-throwing attacks for the fourth consecutive night . . . One of the bombs thrown here last night exploded outside the Ledra Hotel just after the Governor had left a dinner. Another blew off the front door of a British Army officer's home.’Footnote 2 Soon, this unease made way for a sense of loss of control, as oaths of loyalty to the armed struggle were found to circulate around the island, and various Greek radio broadcasters openly supported the Cypriot struggle despite remonstrations from the British ambassador in Athens. Upon reports of a ship carrying explosives to Cyprus, one broadcaster noted: ‘What would you expect it to carry? Gifts from Santa Claus? It would be guns and gunpowder, so that the Cypriots may fight for their freedom.’Footnote 3

The 1950s cemented a paradigm shift with regard to European colonialism that had started at the end of the Second World War. Ongoing anti-colonial struggles gained new momentum, further strengthened by solidarity movements within the decolonising world. But decolonisation entailed more than the handover of sovereignty to a once dependent territory. Even if many British officials recognised that the tide had turned, strategic and ideological considerations stood in the way of a straightforward retreat. That is not to say, however, that decolonisation wars were inevitable. As Martin Thomas argues in Fight or Flight, they were chosen.Footnote 4 In practice, as was the case with Cyprus, this ‘choice’ was made within the context of a declared state of emergency.

Violence and the politics of exception become especially apparent in colonial settings. The state of emergency creates a thin line between legality and illegality, which Victor Ramraj, in his study of the emergency powers in Asia, defines as the ‘emergency powers paradox’. The paradox lies in the fact that the state, in its attempt to preserve legality, takes measures that under different circumstances would be considered illegitimate.Footnote 5 The state of emergency thus creates a new but precarious reality, often accompanied by discourses of extreme peril and threats to public safety, but covered with a cloak of legality. In this form, the state of emergency acted as a bridge between disparate colonial spaces. As a counterinsurgency method, it was developed in colonial settings, and evolved in new ways during the decolonisation era. As a legal tool, however, its coloniality is often overlooked by both theorists and researchers.Footnote 6 This article views the legal framework of the state of emergency as one of several ‘technologies of emergency’ that were deployed during post-war decolonisation struggles generally, and the Cyprus Emergency specifically. In general, the coloniality of the island has not been a prominent feature in Greek historiography, which has tended to emphasise the international dimensions of the conflict.Footnote 7 By contrast, David French's Fighting EOKA and Brian Drohan's Brutality in an Age of Human Rights highlight the imperial dimensions of British counterinsurgency methods on the island.Footnote 8 This article builds on French and Drohan's work by exploring the intra-imperial roots of those methods, bringing into relief Cyprus's location in the series of colonial insurgencies the British faced in the opening years of the Cold War. In fact, the ‘state of emergency’, as it was termed at the time, was a recurrent phenomenon in the era of decolonisation, and experiences in one colonial emergency informed the next.Footnote 9 As Hussain Nasser points out, colonial territories were not passive recipients but ‘productive forces’ in its conceptualisation and delineation.Footnote 10 The state of emergency as a counterinsurgency tool was aimed at preserving the legality of violent counterinsurgency measures and safeguarding armed forces from possible repercussions.Footnote 11 The state of emergency, therefore, should be framed as a specific mode of governance rather than a spontaneous response to crisis. Achille Mbembe refers to this as ‘necropolitics’: the normative basis of the right to kill, rooted in appeals to exception, emergency, and a fictionalised enemy.Footnote 12 This normative basis was solidified in the 1940s and 1950s through the Malayan, Kenyan and Cypriot struggles, in which a self-consciously colonial state of emergency toolbox was finetuned through successive experiences in these three sites. In addition to legal measures, the ‘technologies of emergency’ in this toolbox included inter-colonial staff rotations, visual propaganda and Cold War rhetoric.

Building the Toolbox: Legal Technologies in Malaya, Kenya and Cyprus

Regardless of the differences between these three sites and the historical contingencies of their respective decolonisation struggles, the state of emergency created common ground between them. During the Malayan Emergency, the British asked colonial officials to conduct a study analysing various aspects of the guerrilla warfare and of the emergency measures for the colony. The director of operations in Malaya submitted a report on the campaign, on the emergency measures and, most importantly, on the lessons learned from them.Footnote 13 As stated in the Review of the Emergency in Malaya: ‘The lessons drawn below have been chosen as those most likely to apply to similar situations which may arise in the future, in which an established government, backed by loyal armed forces and police is threatened by a communist-organised revolt.’Footnote 14

Indeed, Brigadier G.H. Baker, who was director of operations and chief of staff for the campaign against EOKA from November 1955 to January 1957, would later acknowledge that his campaign was based on the Malayan and Kenyan blueprint:

The emergencies in Malaya and Kenya represent an important but limited sample of the experience of this type of campaign. From the military angle, operations were largely confined to a battlefield of jungle and forest, and experience of the many problems of operating in built up areas normally a common feature of such campaigns has been limited. It is suggested that before a firm doctrine is evolved for fighting future campaigns of this type similar studies should be done of Cyprus and, if possible, with French cooperation of Indochina and North Africa.Footnote 15

This points to the concept of the state of emergency as an evolving tactic for colonial settings, rather than a set of separate responses to local crises.Footnote 16

Moreover, the states of emergency in Malaya, Kenya and later Cyprus were accompanied by a specifically colonial discourse. The state of emergency not only created a new ‘legal state’ which permitted extensive police and army action, but also produced new distinctions between an imperial ‘self’ and an insurgent ‘other’. While the constant definition and redefinition of Self and the Other was fundamental to the colonial project, the context of the evolving Cold War gave new meaning to the existing category of ‘(communist) terrorists’.Footnote 17 This framing created a ‘criminal community’ against which the counterinsurgency measures were legalised, and without which the state of emergency could not exist.

Within the reality of the state of emergency, this terminology served a purpose beyond the formulation of a legitimising discourse. Had the fighters been recognised as soldiers, they would have been entitled to the rights of political prisoners if arrested. This was not the case with colonial insurgents.Footnote 18 Drawing from theory on the Algerian War, Verena Erlenbusch-Anderson frames colonial tactics of representation as state violence. The state establishes a ‘climate of terror’ through the representation of the nationalist struggle as terrorism. In effect, this ‘legalises’ state terrorism as counterterrorism.Footnote 19 As a result, the use of extreme measures for the suppression of the insurgency was legalised as ‘internal social defence’. She defines this as ‘polemic terrorism’.Footnote 20 Martin Thomas similarly underlines that ‘insurgents operated in a legal limbo likely to face rigorous punishment under martial law but also subject to criminal penalties as “bandits”, “seditionists”, “terrorists”, or “plain killers”’. This invalidated their political project. But Thomas also notes the economic risks associated with admitting to the realities of a decolonisation war, especially in a settler-colonial context, as ‘a decolonisation war as opposed to more limited troubles might be disastrous, sapping the confidence of domestic publics, colonial settlers, corporations, insurers, and investors, that imperial supremacy would be restored’.Footnote 21

The emergency legislation vested the British officials with far-reaching powers. In Malaya, the high commissioner was authorised to apply whichever regulations he felt necessary for the successful suppression of the insurgency. The emergency laws had a clear effect on larger colonial societies and their relations with British officials. New powers also created a new power paradigm, a shifting of norms resulting in a new status quo. One of the most immediate effects of the state of emergency was the power of detention without trial for up to two years. Under the emergency regulation dealing with detention, a provision was also made for the deportation of undesirable persons, but only with their own consent.Footnote 22 The regulation also allowed collective detention, which permitted security forces to inspect areas and arrest people who were considered to have assisted the insurgents. Large numbers of people could be detained in this way, without specific reasons, but as a precaution. Those framed to have taken part in ‘terrorist’ activities were transferred to ‘rehabilitation centres’. In these areas, they received specific training which prepared them for re-integration into society. The emergency regulations conferred legality on the re-classification of people, reducing them to ‘bare lives’ in the Agambian sense.Footnote 23 This in turn created a system of assessment of behaviour in the detention camps, as people were classed in different categories of detention according to their compliance with detention rules.Footnote 24 Another side of the emergency regime was the application of collective punishments. In response to guerrilla actions, the British authorities proceeded to impose curfews and collective fines.

Although emergency measures undertaken in Kenya resembled those in Malaya, this resemblance also hid important differences between these two spaces, as official reports themselves acknowledged, not least in terms of the type of guerrilla tactics which the British faced. The MCP was defined by the British as the ‘Malayan Branch of international communism’ with the aim to overthrow the government and establish a communist controlled ‘People's Republic’, whereas the Mau Mau movement was considered a secret religious society derived mainly from the Kikuyu, with the goal of driving out the Europeans and later the Asians.Footnote 25 Officials acutely realised that the state of emergency was applied relatively uniformly to very different colonial realities. Chief of Staff Colonel Rimbault made this explicit in August 1953, stating that

experience has so far shown that the tactical doctrine for operations against Mau-Mau in Kenya can be based to a large extent on lessons learnt from operations against the communists in Malaya. . . . There are of course major differences between the two, particularly in climate, terrain and in the characteristics of the enemy. Those do not however form a reason for not profiting by experience in Malaya, and there are many similarities between the two campaigns.Footnote 26

The ‘colonial continuum’ between these two emergencies is most apparent through the officials on the ground. Sir Gerald Templer, mentioned above, passed the blueprint of the emergency regulations enacted in Malaya on to Evelyn Baring, governor of Kenya between 1952 and 1959.Footnote 27 Templer also taught methods of counterinsurgency, especially the rehabilitation method, which was used in both emergencies, to other officials. One of those he taught in Malaya was Thomas Askwith, who proceeded to oversee the rehabilitation process in Kenya.Footnote 28 Askwith's tour report in 1953 stressed that: ‘the detention camps in Malaya were regarded not as punitive institutions but as opportunities to alter the attitude of the communist sympathisers and reinstall confidence in the British colonial government’.Footnote 29 In this way, counterinsurgency methods evolved specifically for colonial contexts, and organisational learning was cemented through inter-colonial staff rotations.

In June 1953, a confidential letter from the Secretary of State for War stated that General Erskine would be appointed commander in chief in East Africa, with full command over all colonial, auxiliary, police and security forces in Kenya.Footnote 30 The governor retained authority over the administration of the colony, but it was stated in the letter that priority should be given to any security and military measures that General Erskine considered necessary for the ‘restoration of law and order’.Footnote 31 Erskine was another important link in the chain that connected the emergencies of the 1950s. In June 1953, General Erskine assumed full control of all operations in Kenya, with the object of defeating all ‘terrorist gangs’, as the Mau Mau were defined.Footnote 32

The positioning of General Erskine as director of operations was a unanimous decision by important members of the colonial office and military staff.Footnote 33 Among those who agreed that a more robust approach was necessary in the Kenya Emergency was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir John Harding. During the Kenya Emergency, Sir John Harding became one of Erskine's confidants. Their correspondence contains details on the positions of the army and the police, on discipline, and the effect that the operations had on political and social life in Kenya.Footnote 34 Harding himself was no stranger to counter-insurgency tactics. After the end of the Second World War, he was posted to Malaya as commander in chief. From 1952 to 1955, his position as Chief of the Imperial General Staff provided him with influence and an active part in the Kenya Emergency. His Malayan experience thus directly informed his approach to further counter-insurgency campaigns.

The role that Malaya played in Harding's thinking is apparent in other ways as well. In 1955, Brigadier Mark Henniker wrote a book on the Malayan Emergency: Red Shadow Over Malaya.Footnote 35 In this book, the discursive framing of the emergency as outlined above is clearly apparent. Malayan fighters are described as ‘bandits’ and ‘terrorists’.Footnote 36 Henniker explains the advantage of the state of emergency over martial law, which might increase support among the insurgents because martial law would provoke, in his words, ‘miscarriages of justice’.Footnote 37 Harding provided the foreword for the book, commending it ‘to all readers as a story of which not only Brigadier Henniker and his gallant troops but the whole British people can justly be proud’.Footnote 38 The Malayan Emergency was thus explicitly designated as a case from which lessons for the future might be drawn.

Harding also utilised his own experiences in Malaya in his role as advisor in the Kenya Emergency. At the end of February 1954, both Harding and the Colonial Secretary, Oliver Lyttleton, visited Erskine in Kenya to observe the situation.Footnote 39 The course of the Kenya Emergency was not abandoned into the hands of inexperienced people. On the contrary, military men with direct experience of previous emergencies were sent in to manage the next one. Both the Malayan and Kenya emergencies created a depository of knowledge ready for future use.

It stands to reason, then, that Sir John Harding, with the Malayan and Kenya emergencies among his military accolades, was later appointed governor during the Cyprus Emergency. Again, it should be noted that, as had been the case between Malaya and Kenya, there were substantial differences and historical and geographical contingencies that set the Cyprus Emergency apart from these precedents. Nonetheless, the same set of emergency measures was enacted.Footnote 40 A state of emergency was declared, and the officials on the ground did not only work from the same blueprint but had themselves used it in the past, particularly Sir John Harding. In this way, Cyprus became another Cold War era decolonisation conflict.

‘Terrorism Must Stop so that Democracy Can Begin’Footnote 41

Grivas knows very well that the Englishmen will never abandon Cyprus . . . The ongoing violence is in vain.Footnote 42

The bombings in different parts of Nicosia, with which this article opened, marked the prelude to what the British called the ‘Cyprus Emergency’. The quotes above are extracted from British propaganda leaflets distributed in Cyprus, and they reflect the centrality of Cyprus to the British imperial project. Although, as Andrekos Varnava notes, the British never had much control over political violence on the island in the first place,Footnote 43 the outbreak of the emergency nevertheless came as a surprise. In colonial bureaucratic discourse, the Cypriot people were generally described as docile, peaceful and unlikely to proceed with organised revolt.Footnote 44 According to many British officials, including Brigadier Baker above, any violence on Cyprus would likely follow the form of the 1931 riots, that is, ill-organised and of short duration.Footnote 45 Instead, the Cyprus Emergency became an integral part of the counterinsurgency operations of the decolonisation era. Its place in the colonial archive, particularly in the ‘migrated archive’, mirrors this assertion.Footnote 46 In the archive, the files on the Cyprus Emergency do not just bear out organisational learning from previous colonial emergencies – the Cyprus operation was literally archived as an extension of the Malayan and Kenyan emergencies, marking it for posterity as the continuation of a set of measures implemented half a world apart.

But even within the continuum of emergencies that occurred during the decolonisation struggles of the early Cold War era, Cyprus had a few key characteristics. Firstly, the island consisted of two communities, the Greek Cypriots and the Turkish Cypriots. Both communities felt a special relationship with Greece and Turkey respectively. With the beginning of the decolonisation war against Britain, divisions between the two communities were exacerbated through the British use of the Turkish Cypriot community in the police forces. Secondly, the Greek Cypriots did not seek independence, as was the case in most other colonies, but enosis (union) with another country, which raised the question whether Cyprus was an international problem, a political problem, or a colonial problem.Footnote 47

Another key element in the Cyprus case was the strong position of the Greek Orthodox Church, which had direct access to and influence on political matters. For the British administration, the power of the Church threatened the future of the British on the island. The British administration considered the proscription and exclusion of the clergy from the legislature as ‘it provides the background in which EOKA terrorism is able to flourish’.Footnote 48 In the 1950s, Archbishop Makarios III represented the Church's power. Makarios was both a religious and a political figure and a strong supporter of enosis. The strong religious sentiments among the Greek Cypriots allowed Makarios to use his position of Archbishop as a persuasive political weapon. Makarios controlled the political aspect of the struggle, whereas George Grivas was the leader of the military campaign. Harding described Archbishop Makarios as a man of ‘great ambition’.Footnote 49

The threat that the EOKA struggle posed to British interests led the administration to consider the application of a known and successful tool in colonial counterinsurgency: the state of emergency. However, the sitting governor, Robert Perceval Armitage, was not considered the best person for handling the responsibility of a state of emergency, which led to the positioning of Field Marshal Sir John Harding into that role.Footnote 50 At first glance, this was a surprising move. Armitage was an experienced colonial administrator with the type of life trajectory which often accompanied it. Born in India as the son of the commissioner of police in Madras, his first posting had been as a district officer in Kenya in the 1930s, followed by a post-war career as the financial secretary of the Gold Coast.Footnote 51 When the first bombs exploded in April 1955, Armitage read the situation correctly. As the struggle intensified, he requested permission to declare a state of emergency in July but was denied. The only instrument he could wield, for the time being, was a new Detention of Persons Law enacted on 15 July, which he used to detain known militant members of EOKA. What Armitage lacked, however, was proven experience with other colonial emergencies. His previous posting, the Gold Coast, had been on a very different path and would gain independence in 1957. And so, with actions against the British on the rise, most notably after the burning down of the British Institute on 17 September 1955, a more forceful approach to the crisis was considered inevitable. By then, Armitage had been replaced by Harding. The state of emergency which Armitage had initially recommended was indeed declared, but Armitage himself was reposted to Nyasaland.Footnote 52

Seen from this set of staff rotations, Cyprus was not just another colonial territory: from November 1955, it was also another colonial emergency. The replacement of Armitage with Harding should be read in the context of efforts to regain control and ensure British interests in the area. With this replacement, the approach to the Cyprus problem ceased to be diplomatic and became a military issue. An experienced military man was called to a position hitherto held by diplomats. Harding was in office from October 1955 to October 1957, and declared the state of emergency to ‘restore law and order’ just a few weeks into his tenure.Footnote 53 This placed all police and military operations under his command, while before the emergency the command and control structure had consisted of the governor, the colonial secretary, the commander of the Cyprus district, the senior RAF officer, the attorney general, the resident naval officer, the commissioner of Nicosia and the commissioner of police.Footnote 54

This was accompanied by several additional changes to the administrative structure of the island. Harding abolished the appointment of a director of security and instated a chief of staff instead, who reported directly to him on the internal security campaign.Footnote 55 Because he found the Cyprus police force small and ill-equipped, in addition to expanding the force he petitioned the colonial office for use of the military in urban security. With the ensuing royal order, the military gained the same rights as the police force.Footnote 56 Harding was determined to bring the EOKA insurgency to an end, using tactics previously applied in Malaya and Kenya. Charles Foley, journalist and director of the Times of Cyprus, described the new governor as a smart and strict man with a notable military career.Footnote 57

One of Harding's first tasks when he arrived in Cyprus was the introduction of a liberal constitution. In the context of the evolving Cold War and the strategic location of Cyprus vis-à-vis both the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean, this was felt to best safeguard British dominance over and interests in the island. Harding opened negotiations with Archbishop Makarios to this effect as soon as he entered office.Footnote 58 In the meantime, however, Harding considered military dominance a necessary step on the path to success.Footnote 59 Military success, in his mind, could not be achieved without declaring a state of emergency.

The emergency legislation was described as necessary because of the ‘weakness in the normal laws to maintain law and order’.Footnote 60 The emergency legislation covered a wide range of laws that dealt with restriction of movement, curfews, freedom of speech, control of media, restriction of assembly of more than five people, arrests without warrant, detention, collective measures of control and punishment, exile of unwanted people, propaganda, control of ports and movement.Footnote 61 Lawrence Durrell, who served in the intelligence service for two years, notes: ‘the gradually growing pressures upon the terrorists began to react upon the civil population, upon industry, upon business and entertainment . . . Stage by stage the island became an armed camp, spreading the sense of suffocation’.Footnote 62 An organisation was built up, on models previously used in Malaya and Kenya, for running security operations on a tripartite or three-member team basis in each of the districts.Footnote 63

‘The Detention of Persons, Regulation 18B’ of 1955, without trial law, drew a lot of criticism to the administration, especially with regard to human rights concerns. However, from the point of view of the British administration, it was considered necessary for ‘the breakup of the terrorist organisation’.Footnote 64 It included a categorisation of how dangerous a person was considered to be. If the person was low on the list, restriction orders were issued against them. For those labelled as dangerous, the administration proceeded with detention without trial. The detention camps themselves were modelled on the Malayan and Kenyan examples. As Baker noted in his report: ‘in the camp good work was done by the Government welfare staff in conditioning men and youths to a return to normal life’.Footnote 65

In addition to the ‘Detention of Persons’ law, collective measures for control and punishment were implemented. These collective punishments were meant to serve a dual purpose: first against EOKA, and secondly as a deterrent toward the population at large. The measures included collective fines, curfews, closure of places, eviction from buildings and restrictions of movement. Authorities considered these collective punishments vital in order to ‘bring home to the ordinary people the hard fact that the results of terrorism include hardship to themselves and so to create conditions predisposing people in favour of a political settlement’.Footnote 66 Both the army and the police had the right to stop and search any individual on the street for inspection. Security forces had also the right to break into any public or private space for inspection at any time.Footnote 67 When villagers were not willing to share information about EOKA activities in the surrounding region, collective fines were imposed.Footnote 68

Possession of firearms, bombs, guns and ammunition was forbidden under the emergency legislation. Breach of the law could result in the death penalty. Here, however, Cyprus's proximity to Europe does appear to have set it on a slightly different path: the death penalty was not applied as extensively as in other colonies.Footnote 69 Over the course of the Cyprus Emergency, many people were sentenced to death, but nine death sentences were carried out. The hanging of these nine EOKA fighters further widened the gap between the colonial administration and the general population.Footnote 70 In the eyes of the people, the hanged were turned into martyrs for the cause. In 1958, twelve people who were sentenced to death were pardoned. The example of the death penalty law shows how, although the state of emergency was accompanied by an increasingly fixed set of colonial counterinsurgency measures, these were adapted when faced with realities on the ground.

Operational and preventive curfews were also widely used during the emergency. The operational curfew was imposed for a few hours or days in order to assist the actions of the security forces. The preventive curfew was used both as a means of avoiding riotous assemblies and also of restricting EOKA's freedom of movement.Footnote 71 One notable example is the curfew that was imposed in Nicosia for seventy-two hours after murderous offences on Ledra Street. Chief of police Martin Clement, after imposing the curfew, stated that now was the time for everyone to give to the police the information needed. Every household was given an envelope into which to insert information on EOKA activities. Only empty envelopes were returned.Footnote 72 This, too, was a sign that the emergency measures were not just ineffective but contributed to further alienation from the administration. But as people were deprived of their political rights and their bodies became objects of political dominance, control over the person in specific and the whole of the society became critical for the government.Footnote 73

This analysis of the Cyprus Emergency builds on Brian Drohan's work on the role of law in legitimising colonial counterinsurgencies, and the contrast between these violent contestations over colonial rule and the professed values of the post-war order.Footnote 74 Drohan's work places evolving human rights frameworks and counterinsurgency methods in conversation with each other.Footnote 75 Indeed, Harding's decision to declare a state of emergency created a new ‘legal space’ which under different circumstances would have been considered illegal. In that sense, our argument for the coloniality of the technologies of emergency used in the Cyprus conflict follows Drohan's line of reasoning. Drohan underlines that ‘as colonial officials claimed legitimacy from the rule of law, they simultaneously adopted wide-ranging executive powers on the basis that such powers were necessary to protect the colonial state’.Footnote 76 The appointment of Harding and the severity of the measures implemented under the state of emergency show that attempts to regain control of the island drew directly from the colonial toolbox.

Visual Propaganda and Cold War Rhetoric as ‘Technologies of Emergency’

Control was enacted in other ways as well. The counterinsurgency toolbox was not limited to restrictive measures alone. It also contained tools intended not to alienate but to persuade people of the need to collectively combat an outside threat. This too was a continuation of earlier colonial counterinsurgency campaigns.Footnote 77 As noted above, Britain's legitimation of its colonial wars necessitated the construction of a criminal community. Through propaganda leaflets, further distinctions were made between ‘self’ and ‘other’, with the EOKA fighters cast in the role of terrorist outsiders. The British proceeded with the creation of leaflets, which mostly consisted of simple sketches that were so clear that further descriptive text was largely redundant. In the leaflets, the British portrayed the EOKA fighters as threatening the very fabric of society [Figure 1].

Figure 1. British propaganda leaflet: ‘What does Grivas have to offer?’Footnote 81

In this first image, George Grivas and Grigoris Afxentiou – second in rank in the organisation – are shown in a dark cave. The interior of the cave is set up as ‘Estiatorion EOKA’, or ‘EOKA restaurant’. It is a shabby affair: the roof is leaking, the tablecloths are frayed, the plates are chipped and the wine glasses have razor-sharp edges. The makeshift furniture appears haphazardly constructed from driftwood. The eye is drawn to Grivas, dressed as a waiter with a bow tie but still wearing an ammunition belt. He is presenting a serving platter with a skull on it to the viewer. Afxentiou, quite literally the secondary figure, is similarly dressed in a bow tie and jacket, while wearing a side-arm and ammunition belt. He is standing at ‘his’ bar (‘Bar Afxentiou’, says the sign), using the restaurant's supplies to create bombs. On the table lies a menu with the words: ‘Violence’, ‘Hatred’, ‘Fear’. The viewer is invited to consider the menu as the answer to the question asked in the caption underneath: ‘What does Grivas have to offer?’ Every detail in the image serves to convince the viewer that EOKA offers nothing but precarity, if not outright death.Footnote 78

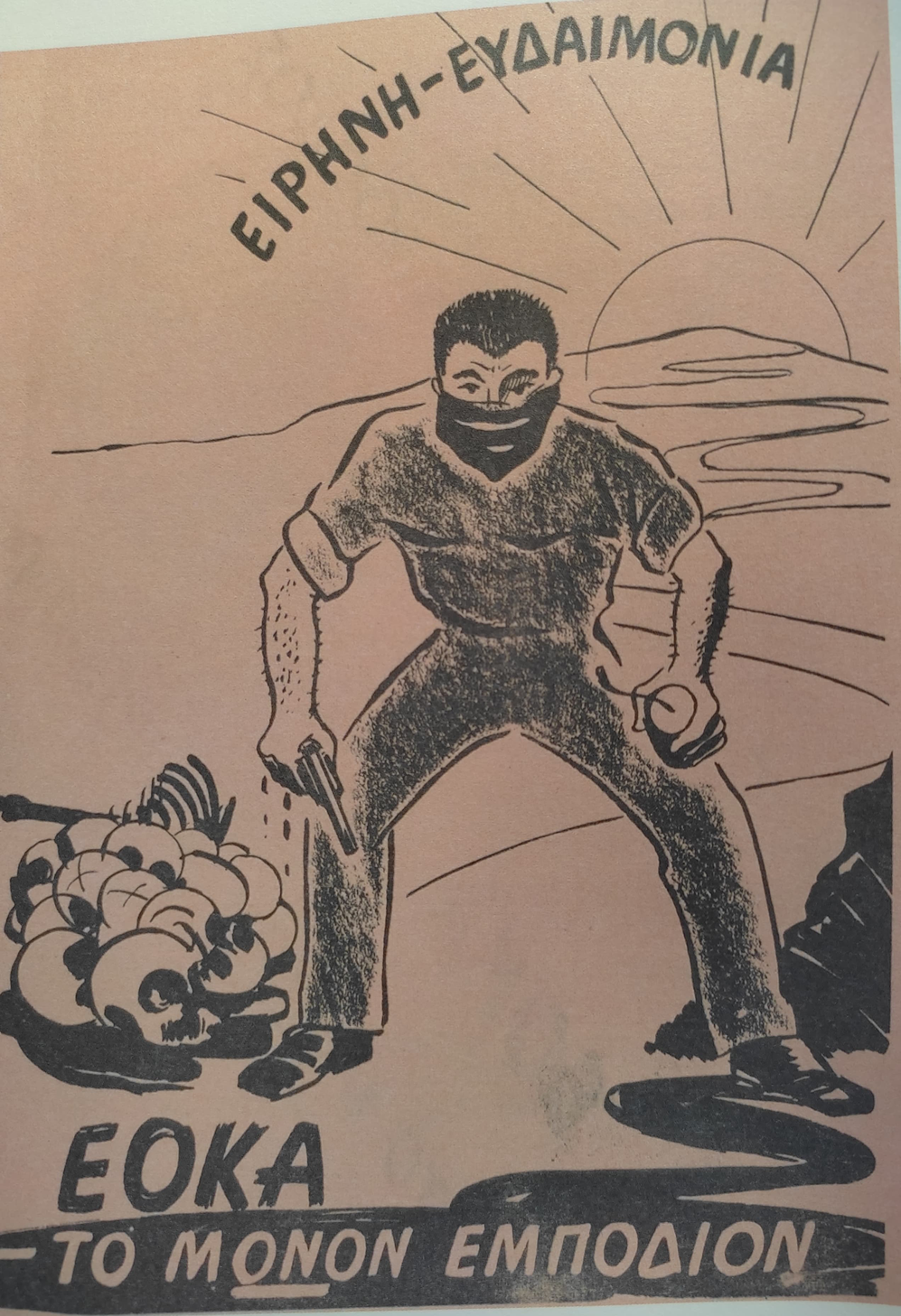

The same idea of extreme precarity is apparent in the second leaflet [Figure 2]. In its simplicity, this image is even stronger. An EOKA fighter is depicted as a literal obstacle on the road to peace and prosperity. He's blocking the path and there is no way around him. To his left, there is a pile of skulls. To his right flows a river of blood. The figure itself is portrayed with strong masculine features and has assumed a threatening stance towards the viewer. He wears a black mask to conceal his identity and holds a gun in his right hand and a bomb in his left hand.Footnote 79 This image clearly intends to evoke a terrorist ‘other’, with all the attributes that entails: a harbinger of fear and death, with raw characteristics and no signs of mercy. His dark clothes add a further contrast to the peace and prosperity – ‘ɛιρήνη’ and ‘ɛυδαιμονια’ – beyond the horizon, a new day just outside of reach, the sunrise beyond the mountain. Here too, the EOKA fighters were excluded from the body of society as terrorists, dangerous for the well-being and progress of others. With this definition of a terrorist ‘other’, the British represented themselves as the protectors of society, in the process conflating the colonial administration with the Cypriots in the ‘self’. In this way, propaganda served to further assist in the legitimisation of the state of emergency.

Figure 2. British propaganda leaflet: ‘EOKA. The only obstacle.’Footnote 82

During the state of emergency, the limits of legality for the state were extended. Actions that would normally be considered illegal were now framed as existing within a ‘lawful’ environment. As Kahn notes: ‘Criminals have no right of self-defence against the police . . . There is a corresponding depoliticalization of the violence of crime: it is not political threat but personal pathology. Law enforcement aims to prevent the violence of the criminal from becoming a source of collective self-expression.’Footnote 80 This distinction between the enemy and the criminal applies to a new way of irregular warfare. The ‘belligerents’ in the decolonisation wars were not armies but irregular forces which were hiding in remote areas and who attacked suddenly against specific targets. The discursive formation of the EOKA fighter, however, must also be analysed within the framework of the Cold War. The decolonisation wars of the 1950s cannot be seen as separate from wider Cold War notions and anxieties, particularly with regard to communist threats.

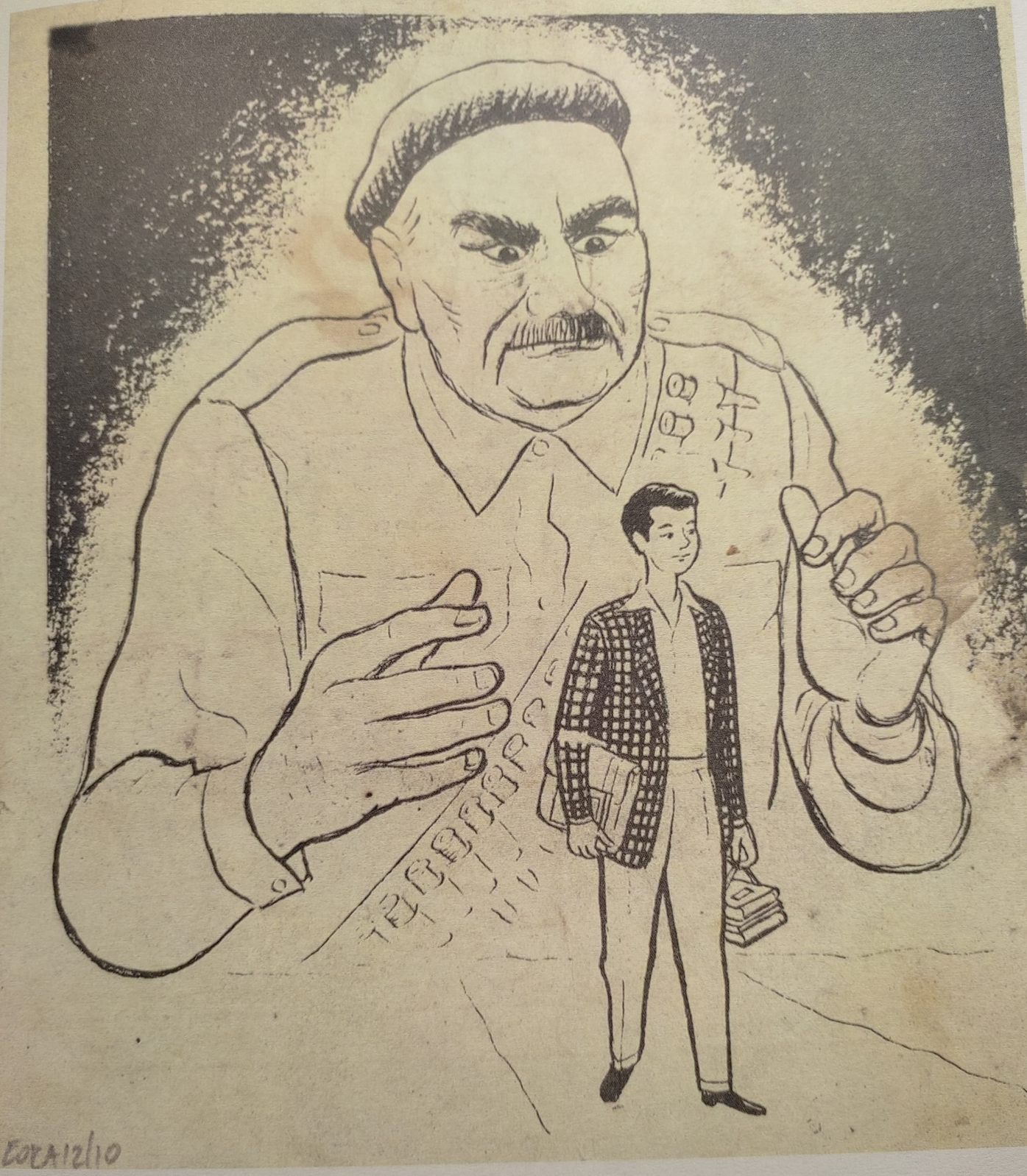

This is illustrated by the third leaflet, which draws from a more global vocabulary of Cold War imagery [Figure 3]. It portrays once more the leader of the EOKA organisation, George Grivas, but not as a waiter in a struggling and dilapidated restaurant. Here, he is portrayed as an evil menace, hovering over an unsuspecting schoolboy. But despite the familiar Cold War era visual rhetoric of the image, this leaflet does reference a specific Cypriot historical contingency, which is the participation of a considerable number of schoolchildren in the struggle. Greek-Cypriot teenagers contributed by participating in riots and other actions to provoke police reaction. The most striking element of this leaflet, however, is the figure of George Grivas himself. As is the case with Figures 1 and 2, this figure displays raw characteristics and is portrayed in a military outfit. He also appears ready to pounce from behind, reaching out with both arms to the schoolchild going about his business. But is it really Grivas? The figure's facial characteristics do not resemble the rather thin-faced Grivas so much as those of Joseph Stalin, or at least a mash-up between the two. This fits a larger Cold War pattern of conflating decolonisation movements with communist ones, as well as the expectation that anti-imperialist activity was directed at least in part from Moscow. The Cyprus insurgency was no exception to this rule. With the depiction of Grivas as Stalin, the British directed the discussion towards the fight against communism. There is considerable irony in this, given the fact that George Grivas was a well-established anti-communist. Just a few years earlier, Grivas had founded and led the secret anti-communist organisation ‘X’.Footnote 83 Nevertheless, the global Cold War, in the Westadian sense of the term, provided the vocabulary to continue colonial interventions in a different dialogue.Footnote 84 Drawing from the visual repertoire of the era helped to confer legitimacy onto the state of emergency on the island.

Figure 3. British propaganda leaflet: Depiction of the leader George Grivas.Footnote 86

On the Ground: Escalations of ‘Minimum Force’ between Decolonisation and the Cold War

The Cyprus Emergency attracted much publicity concerning the British military actions. Reports from the island alleged the use of torture as techniques of interrogation. As Jean-Paul Sartre would note a few years later in his work on Algeria, torture was not only an issue in totalitarian systems but also in the progressive democratic West: ‘Today it's Cyprus and it is Algeria; all in all Hitler was just a forerunner.’Footnote 85 In the continuum of early Cold War era counter-insurgency campaigns, torture as aimed at the extraction of information was certainly part of the repertoire. Human rights abuses were alleged in both Kenya and Cyprus. The collective punishments, detention camps and executions all contradicted the standard of ‘minimum force’.Footnote 87 Rather, the challenge was to confer legitimacy upon the measures taken, in order to be able to argue that they were in accordance with standing law. The idea of ‘minimum force’ may have been projected as the leading principle in British intervention, but the reality on the ground was different. Secretary of State for War Christopher Soames noted that every soldier in Cyprus knew of the concept, but freely admitted that it was not always followed: ‘we must never forget that the role of the security forces is to conquer terrorism, and there will be many incidents when the minimum force necessary will be quite a lot of force’.Footnote 88

How did the application of force affect daily realities in Cyprus during the emergency? In 1957, in an attempt to capture George Grivas, security forces imposed a curfew on Milikouri village which lasted for fifty-four days. Residents were not allowed to leave their houses between 7pm and 7am. Soldiers searched everything and everyone.Footnote 89 These kinds of long-term curfews, along with the detention of thousands of Greek Cypriots in the detention camps of Kokkinotrimithia, Polemi, Kyreneia Castle, Pyla and Pergamos, further strengthened allegations against the British government.Footnote 90 As noted above, the use of curfews and detention camps were drawn from the Malayan and Kenyan emergencies. Life behind barbed wire became a ‘new normal’.

Outside of the camps, the EOKA campaign influenced daily life in its own way. The military campaign itself consisted of armed groups that fought in the Troodos and the Kyreneia mountain ranges. But in addition to guerrilla actions, EOKA had strong connections to Cyprus's more populous areas. In cities and villages, EOKA activities consisted of bombing British targets, but also of the assassination of targets that collaborated with the British, including Greek-Cypriots ones. A British report mentions various targeted assassinations against Greek Cypriots: ‘on the 15th January at 5pm a Greek-Cypriot, Kypri Menicou, aged 20 years was in a coffee shop at Psomolophou Village, Nicosia when three masked men dressed in priests clothing, entered the coffee shop and shot him dead.’Footnote 91 On the EOKA side, too, the lines between ‘self’ and ‘other’ were clearly defined.

As noted above, another element of the EOKA campaign was the assistance of Cypriot youth in rioting and minor missions. The provisioning of troops and the provision of shelter was largely the purview of Cypriot women. However, women were also used in targeted assassinations, as suspicion was much less likely to fall on them.Footnote 92 Former EOKA fighter Mimis Vasileiou recalls the important contribution of women to the struggle:

the women were amazing, women assisted in the actions . . . If I had a mission to go and assassinate an Englishman, I would not carry the gun with me, it was not easy because there were inspections everywhere. The women undertook this mission. They hid the gun in their clothes, they proceeded to the assigned area, left the gun there, the fighter took the gun, proceeded with the assassination, he put the gun back in the assigned spot and then the woman returned, took the gun, and left.Footnote 93

Although women were not part of the active campaigns in the mountain ranges, they assisted the fighters in other ways. This pattern of intimidation of and assistance from Greek Cypriots shows the complex relationship between EOKA and the general population.Footnote 94

As a consequence, the British had to consider actions not only to defeat the armed groups in the mountains but also to control EOKA supporters among the general population. This raises the question of whether it is possible to speak of a ‘dirty war’ in Cyprus. During the course of the emergency, a series of allegations of ill-treatment began spreading against the British security forces. On the one hand, these allegations were part of a larger propaganda war initiated by EOKA, and received official appeal through the Greek government.Footnote 95 On the other hand, credible allegations of torture have come to light.

Thasos Sofokleous is a former EOKA fighter who testifies that torture was used as an interrogation method, and that he was one of the fighters who underwent torture during the emergency. During the early years of the struggle, Thasos Sofokleous was a university student in Athens where, along with other Cypriot students, he took part in marches in support of the enosis cause. It was not long until they decided to go to Cyprus to fight for the cause. Their first stop was the island of Crete, where they were trained and prepared for irregular warfare. From there, they proceeded to Cyprus and were placed under the orders of George Grivas. Sofokleous was positioned in the area of Pentadaktylos for six months, along with the well-known EOKA fighter Grigoris Afxentiou, who appeared in the propaganda leaflet discussed above [Figure 1]. When Afxentiou was repositioned to a different area, Sofokleous assumed leadership of his armed group. On 4 August 1956, Sofokleous and his team were discovered and arrested. According to Thasos Sofokleous, his whole group was tortured. As the leader of the group, he was considered in possession of the most information, and was tortured more severely.Footnote 96 Sofokleous distinguishes two kinds of torture, psychological and physical. The aim of both was to extract information on the secrets of the organisation.

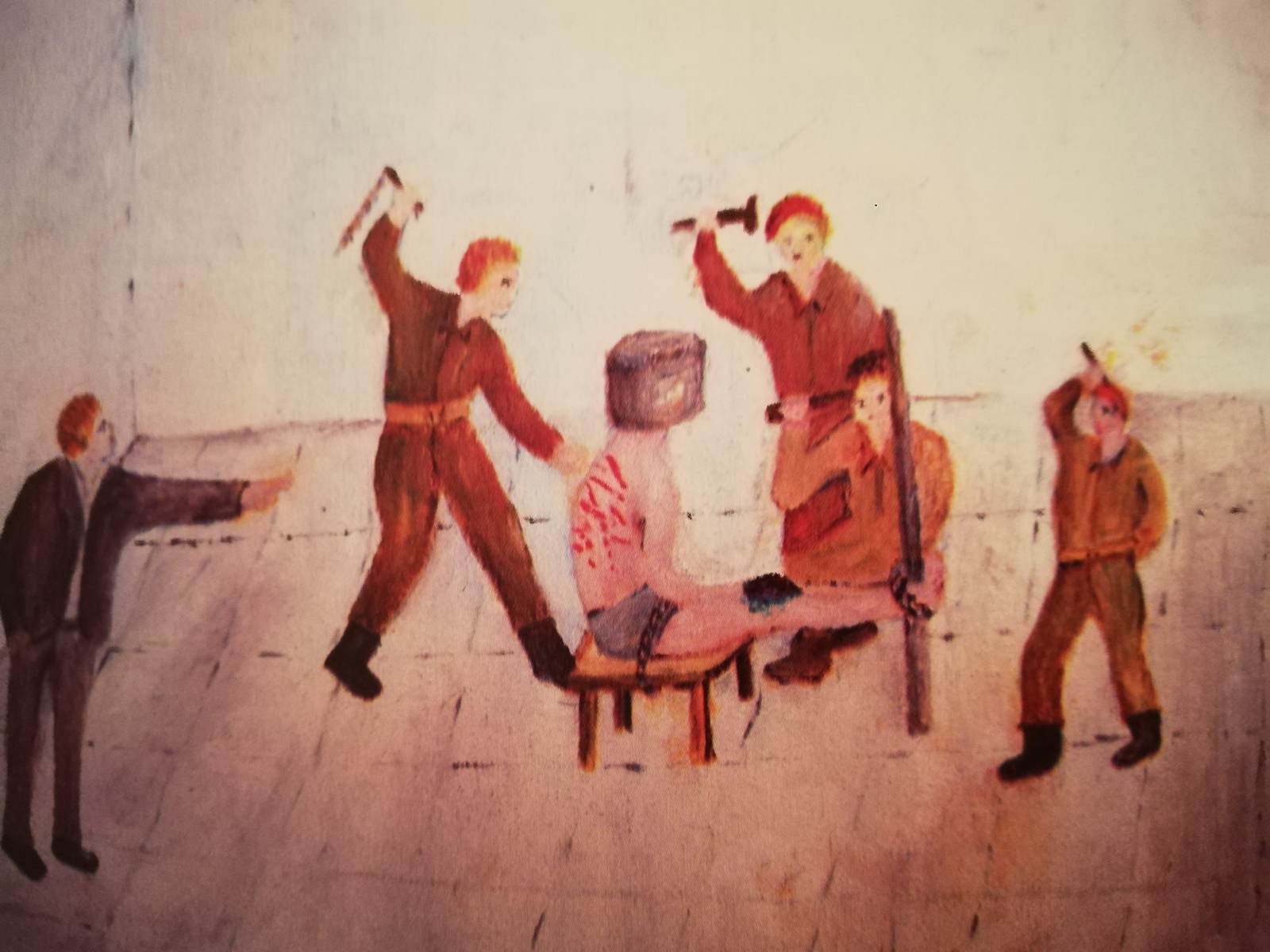

One act of torture remained etched in his memory and compelled him to turn it into a painting [Figure 4]. ‘They bound me to a chair … I was only wearing shorts. They bound my feet across on a pillar, my hands [were also] bound. They put on my face a piece of blanket and placed a silver bucket on my head. They hit me. Under my bare feet … on the knees, on my back, and on the head with hammers.’Footnote 97 The torture included whipping and various other methods. The ultimate aim of the torture was for the prisoner to confess. According to Sofokleous, when the person under torture eventually fainted, they would throw a bucket of water on him. If he woke up, the procedure would continue. If not, they would shoot him in the back and then say that he was shot while attempting to escape. Sofokleous claims he endured torture for seventeen days without revealing any secrets of the organisation or the struggle.

Figure 4. Painting by Thasos Sofokleous.Footnote 101

Sofokleous’ captivity did not end with the prison cells of Larnaca. He and other captured fighters were transferred to prisons in the United Kingdom, as they were considered too dangerous to remain in Cyprus. In 1957, he was transferred to Wormwood Scrubs along with eight other fighters: Socrates Loizides, Fotis Christofi, Epifanis Papantoniou, Andreas Mappis, Grigoris Louka Grigoras, Vias Leivadas, Nicolas Loizou and Evangelos Panagiotou.Footnote 98 This did not mean, however, that they were now removed from the struggle or disappeared into obscurity. Rather, the prisoners, while in Wormwood, forwarded to the Colonial Office allegations of ill-treatment that occurred during their time in Cyprus. Footnote 99

The Greek Cypriots, mainly represented by EOKA, Makarios and, in the end, the Greek government, created a strong counter-narrative which accused the British security forces of excessive violence. Another former EOKA fighter, Mimis Vasileiou, has dedicated part of his life after independence to the writing of a volume on the concealed torturing that took place during the struggle. The book is a concise work which includes testimonies, newspaper articles and British archival documents. The book alleges fourteen cases of death which, according to the Greek Cypriots, occurred as a direct result of torture.Footnote 100

The case of EOKA fighter Georgios Nikolaou offers an example of how these cases are presented in Vasileiou's book. Nikolaou had been responsible for the EOKA actions in the area of Pyrgos. When he was arrested in 1956, he was transferred to the camps of Leukas-Xerou where, according to his brother, he was severely tortured. Nikolaou was reported dead some days before his scheduled court case. According to the official report, he was shot by a guard as he tried to escape. During the identification process, however, his brother noticed the bullet wound, but also saw clear signs of torture. His legs were both broken. The Greek-Cypriot side therefore alleges that the death was a result of torture, and that the story of escape was a cover-up.Footnote 102

This example is illustrative of a discourse that took shape over the course of the struggle but continued to evolve in the decades after independence. If the British framing of the Cyprus Emergency cannot be seen as separate from Cold War anxieties, the Cypriot framing of the emergency was markedly influenced by the recent experience of the Second World War. As David French notes, torture allegations against the British took on dimensions that drew from wartime memory and invited parallels with German atrocities.Footnote 103 Even if the counterinsurgency tactics themselves were part of a continuum of early Cold War era colonial emergencies, this is a reminder that their location in public memory is always locally and historically contingent. In this sense, the emergency toolbox's discursive framing of the Cyprus Emergency as a Cold War conflict largely failed to convince those who lived through it.

Conclusion

With the London-Zurich Agreement of 1959, the Cyprus Emergency came to an end. The United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey served as guarantor powers in an uneasy arrangement of bicommunal consociationalism. Cyprus had gained its independence. The regional powers who signed the Treaty of Guarantee, as well as the subsequent failure of the treaty to prevent the partition of the island, have since combined to obscure the coloniality of the Cyprus Emergency further. However, the Colonial Office conferred extensive powers onto military men like Sir John Harding, in hopes of bringing the insurgency to an end, as had been the case in Kenya and Malaya previously. The counterinsurgency toolbox developed in the early post-war years was also used on the small island in the Mediterranean. British divide-and-rule methods, such as the composition of the police force noted above, increased tensions between the two communities, which exacerbated the communal conflict which eventually led to the creation of the green line in 1964, which partitions the Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot communities to this day.

The state of emergency created a new power paradigm for use in post-war decolonisation struggles. The organisational learning from its successive use in Malaya, Kenya and Cyprus shows how the concept evolved into a coherent toolbox for colonial counterinsurgency by offering a new legal reality to aid in the preservation of colonial rule. It conferred legality onto the implementation of detention without trial, curfews and restriction of movement. On the ground, security forces had considerable freedom of action, of which the law that prevented prosecution of any member of the security forces by a civilian is the strongest example. Inter-colonial staff rotations further facilitated this organisational learning. Having built a repository of knowledge from the emergencies in Malaya and Kenya, Sir John Harding and other British colonial officials applied this knowledge to the insurgency on Cyprus.

However, this toolbox contained ‘technologies of emergency’ beyond the imposition of legal frameworks. The use of propaganda leaflets was intended to sway public opinion, or at least to sever links between the insurgents and the general population. These leaflets relied on a simple but powerful visual vocabulary that required few literacy skills from their viewers. While the propaganda examined here showed scenes that were easily recognisable to those who lived through the insurgency, the visual vocabulary itself drew from a more global Cold War idiom. This self-conscious ‘Cold Warification’ of post-war decolonisation struggles should be seen as another technology of emergency, as it allowed colonial wars and the preservation of empire to be seen in a different light. The discursive framing of the insurgency as a communist threat legitimised counterinsurgency measures by placing them in a Cold War setting.

Finally, the state of emergency is a useful lens through which to bring the overlooked colonial character of Cyprus into view, allowing the island to be written into the history of post-war decolonisation. Scholarly research has tended to favour the diplomatic dimensions of the conflict. The state of emergency, by contrast, allows us to glimpse the island's struggle for decolonisation within the context of the early Cold War. Cyprus was part of the continuum of post-war emergencies through the counterinsurgency methods used in the conflict, and through the circulation of the officers who implemented them. Local amendments existed in each location, confirming that the inherently hybrid character of the state of emergency was a useful tool regardless of the historical specificities of each conflict. The toolbox of emergency technologies was a versatile one. In that light, the Cyprus Emergency should be seen as a key episode in the series of British decolonisation conflicts in the early Cold War era.

Acknowledgements

The authors are especially grateful to Thasos Sofokleous and Mimis Vaileiou for sharing their memories. They would also like to thank Anne-Isabelle Richard, Lydia Walker, Brian Drohan, and the journal's anonymous reviewers, for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.