1. Introduction

The expropriation of the peasantry has been widely considered a condition for the development of agrarian capitalism.Footnote 1 The forms and especially the chronology of this expropriation would mark the differences between England (and later the Low Countries were also added) and France and a good part of the European continent, where the ownership of land remained in the hands of the peasants until the end of the eighteenth century and even the beginning of the nineteenth.Footnote 2 French historians have never, however, shared this interpretation, let alone the idea of an alleged economic backwardness in France, for not following the same path as England (and the Low Countries) and having experienced greater resistance from the peasant ownership of land and more durable over time. In France (and also in Iberia as we will see in this article), the spread of rural credit and the dynamism of the land market did not result, in general terms, in the dispossession of the peasantry, which continued to maintain its ownership and rights over land during the late Middle Ages and much of modern times. On the other hand, the idea that innovation and economic growth could only come from large entrepreneurs or urban owners, something that happened in England, but not in France, where a secure and complacent peasant tenantry was left in a relatively conservative occupation of its land, is still a prejudice, as many of the studies carried out in recent years on peasant innovation confirm.Footnote 3

The Brenner debate – and much of the subsequent discussion – focused mainly on the contrast between England and France, overlooking Italy and Iberia, which could have contributed important nuances. However, the case of Italy is particularly remarkable for the close connection that historians have established between the spread of rural credit – and indebtedness – and the expropriation of the peasantry. The counterpart of loans was in many cases the loss of land by indebted peasants, unable to repay the credits received. All together, the expansion of rural credit and peasant indebtedness, but also the legal framework of peasant property (allodial title and emphyteutic tenure), the structure of peasant holding – (fragmented into various plots) population growth, the inheritance system and the increase in economic inequality, contributed to activate a dynamic land market, which had winners and losers. Among the first, many creditors – well-off peasants, urban landowners – who took advantage of the arrears of their debtors to appropriate their lands and increase their own farms; and among the latter, failing debtors who could not repay the loans or even pay the interest and saw how they were dispossessed of their plots or even of the entire tenure, offered as collateral or sold judicially to pay back their debts. Some authors, mostly specialists in central-northern Italy, and particularly in Tuscany, have even spoken of a strategy of territorial conquest by urban lenders, who invested in rural credit in order to obtain their debtors’ parcels, taking advantage of the latter's inability to repay the loans, and with them amass large holdings called poderi, managed and worked by sharecroppers called mezzadri.Footnote 4 The expropriation of the peasants, either by taking advantage of their indebtedness, as in north-central Italy, or by other means, constitutes a pivotal theme in the accounts of the transition from feudalism to capitalism. In fact, the literature on the rural economy of the high and late Middle Ages has long established a close correlation between three significant features of the period: the spread of rural credit, the dynamism of the peasant land market and the expropriation of peasant land by creditors, usually yeomen or urban landowners.

However, things were not like that – peasant indebtedness necessarily leading to expropriation – everywhere, nor did the connection between the three above-mentioned processes always work. It would be good to compare the case of northern Italy with that of England and the Low Countries, in which the peasant expropriation process seems to have taken place, and even better to address Western Europe as a whole. In any case, the development in Iberia is more similar to that in France, where peasant property better with stood pressure from lords and urban owners and investors. Peasant expropriation was not there the consequence of the expansion of credit, because the creditors, as we shall see, were not interested in appropriating the land and changing the systems of exploitation, as in Italy and England, but in continuing to receive rents, which did not necessarily translate into a lack of technical and productive innovation or economic backwardness. A more general view, covering the whole of Europe, might show that, although many phenomena were similar in different countries, the consequences were not the same. The use of mortgages to guarantee loans with land or other property helped markedly to increase the spread of rural credit, far beyond that achieved by the main and traditional forms of credit in the countryside, namely instalment purchases, obligations and small usury loans; all of the latter were mostly secured by moveables, including future sales of harvests and existing stock.Footnote 5 If this was not the case in England, this was due, according to Phillipp Schofield, to ‘constraints associated with unfree land’, which prevented contracting mortgages.Footnote 6

These constraints, however, do not seem to have been decisive or even to have existed in southern Europe, where peasants mostly owned the land in allodial title or in emphyteusis. The latter, widespread since the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, had many traits in common with customary copyhold in England and, like the free (allodial) property, it allowed the tenant to sell, exchange, bequeath, donate or lease the land.Footnote 7 Peasants could therefore gain access to a larger volume of credit by offering their plots as collateral or securities. In many regions of feudal Europe peasant tenure was not a compact holding or farm, but a miscellaneous set of small scattered parcels of different qualities, sizes, crops and legal status, since they could be both allodial (free) and subject to the seigneurial domain. In both cases, whether the plots were in freehold or emphyteutic tenure, peasants could mortgage them freely, with, in the second case, the authorisation of the lord, who regularly granted it because he received a share of the sale price (lluïsme / laudemio, alienation fine), which was very lucrative in a period of population growth and inflation but fixed rents.Footnote 8 Both allodial title and emphyteutic tenure therefore allowed peasants to mortgage or sell their land, thus giving rise, on the one hand, to the creation and expansion of consolidated or funded debt,Footnote 9 much more versatile than pledge loans or short-term obligations, and, on the other, to the development and vitality of a very dynamic peasant land market, due to the impossibility of satisfying the debts that weighed on the plot. Not only were lords not against this peasant land market, but they were clear beneficiaries of the increased activity in it, as the manor accounts show.Footnote 10

For one reason or another, because the lords and urban landowners received more profits from the continuous mercantile buying and selling of the land and from the regular rents they received from their long-term credits secured by real estate, the expropriation of the peasant land was not necessarily the best option and the former two options, continuous mercantile transactions in land and regular rents, were considered more beneficial. In this sense, my aim in this article is to analyse whether the expansion of rural credit and the land market led to peasant expropriation, especially in highly urbanised areas, where a greater interest could be presumed on the part of urban landowners to take direct control of farms around the cities. Most historians argue that this was the case in the countryside in central-northern Italy, strongly dominated by the cities and the penetration of urban capital.Footnote 11 It was not, however, in Mediterranean Iberia, a region that was highly urbanised, with large cities such as Barcelona and Valencia, and also with a strong presence of urban capital in the countryside. There, however, unlike in Italy, rather than the dispossession of the peasantry, taking advantage of peasant indebtedness, what creditors pursued was the regular and secure reception of rents, in the form of annuities,Footnote 12 for the loans granted.

How important could this disparity be and how did it reflect the different social and economic structure of the region? How strong were the rights of landowners and peasants? If it was not land, what were creditors investing in loans looking for? And on the other side of the transaction, why did peasant families need credit? For consumption, for investment or for both at the same time? Was peasant indebtedness structural, systemic, and to what extent did it weaken or strengthen the feudal system, based precisely on the receipt of rents, which was what the interest from long-term loans offered in the form of annuities?

To discuss these arguments, I will focus on the kingdom of Valencia, in Mediterranean Iberia, based on judicial documentation, particularly the records of the local courts of some towns and villages from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. The structure of the article, after the introduction, is as follows: in section two, the kingdom of Valencia, the forms of land ownership and the archival sources are presented; in section three, short and long-term credit and indebtedness is studied from notarial and judicial sources; in section four, prosecution of arrears and auction sales of debtors’ assets are analysed; finally, the last section presents results, discussion and conclusions. The nuances are always very important and, in this article, the quantitative approach, based on a sizeable sample of data – thousands of documents from several judicial courts – will alternate with the qualitative one, allowing us to see into individual cases and observe the motives and reasons of the actors, both lenders and debtors.

2. The kingdom of Valencia, the forms of land ownership and the archival sources

The kingdom of Valencia was a new political entity created in the thirteenth century on the lands seized from the Muslims in the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula (the Sharq al-Andalus). These new territories could have been directly annexed to Aragon or Catalonia, as had happened in previous phases of the Christian-feudal expansion towards the south, but instead the conquering monarch, James I, decided to create a new kingdom, with his own laws and institutions, within the framework of the dynastic union that the Crown of Aragon constituted.Footnote 13 The same occurred with the neighbouring kingdom of Mallorca, conquered a decade earlier (1229), and with which that of Valencia had many similarities, since most of the settlers of both new kingdoms came from Aragon and, above all, Catalonia, as well as most of the political institutions, public offices and even the social system (feudalism) introduced by the conquerors to replace the previous one. However, and in this case unlike Mallorca, where the native Muslim population disappeared after a few years, exterminated or sold as slave labour in the Christian ports of the Mediterranean, in Valencia it survived for almost four more centuries, until its final expulsion in 1609. Muslims were still needed to work on the land, because there were not enough Christian settlers to do this. While in the thirteenth century Muslims were still the majority of the population of the new Christian kingdom, in the following centuries their numbers fell to about a third of the total population.Footnote 14 In fact, they continued to be important in the hamlets and villages of the countryside of Alcoi and Cocentaina, studied in this article. Furthermore, many of the features of the institutional order, including the role of notaries in the contracting and registration of debt and the judicial system that pursued arrears and default, were very similar to those of other kingdoms and territories of the Crown of Aragon, but others were not.Footnote 15

Moreover, the kingdom of Valencia was a highly urbanised region dominated by the demographic, economic and political importance of its capital, the city of Valencia, one of the main ports in the western Mediterranean and the second largest city in the Crown of Aragon, after Barcelona. It may have had about 20,000 inhabitants at the end of the thirteenth century, about 35,000 by the end of the fourteenth, and about 70,000 by the end of the fifteenth, when it was not only the most populous city in the Crown of Aragon, but also in the entire Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 16 It was not just the capital: there were also a number of small- and medium-sized urban centres, running from north to south, which acted as regional capitals and markets, replicating on a smaller scale the predominance of the city over the countryside. This importance of the cities, and especially that of Valencia, made agricultural production highly market-oriented, aimed at satisfying urban demand, and also the demands of foreign trade, particularly that of Italy. This means that the country's economy was based on commercial agriculture, whose main products, along with wheat, wine and oil, were profitable crops such as rice, sugar and mulberries. Valencian society was thus urbanised and commercialised, in the sense that English medievalists have given the term,Footnote 17 with numerous fairs and markets established by royal charters between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote 18

Without underestimating the importance of manufacturing and commerce, which were the origins of many fortunes, especially urban ones, land was the basis of power and wealth. There were many forms and even many levels of ownership and possession of land. On the one hand, there was allodial or free land, held in full ownership, which could be sold and mortgaged without the need for any authorisation; it was particularly important in the royal domain, but it was also present on manorial lands. The other predominant form of land ownership was emphyteutic tenure, in which the lord retained the ‘direct domain’, while the ‘useful domain’ or usufruct passed to the tenant, who could alienate it to third parties, through sale, exchange, bequest or mortgage, provided he had the lord's permission and paid him a part (lluïsme) of the sale price. Therefore, not only did both forms of ownership grant peasants great autonomy to use the land as they wished, provided that – in the case of emphyteusis – they paid the corresponding rents, they also allowed them to use it as a mortgage on the loans obtained. Below these two levels, even lower levels could still be found, since peasants who held land in allodial title and those who held it in emphyteutic tenure could in turn sub-let it, also in emphyteusis, to a third party for a short period (generally four years), or turn it over to sharecropping (mitgeria, as mezzadria in Italian). Conversely, only the first two levels – on the other hand the most common – allowed the land to be mortgaged.Footnote 19

Map of the kingdom of Valencia with the towns mentioned in the text

However, although the forms of access to land granted peasants wide-ranging rights over it, two factors worked against them: population growth and the inheritance system. The former reduced the size of the holdings (from an average size of about 9 ha in the thirteenth century to less than 5 ha two centuries later), and the second meant that land was divided equally among all the offspring, which led to the fragmentation of the holdings. As a consequence, land was not generally held in compact units but was split up into highly scattered and isolated plots. Landholdings were therefore continuously being restructured; parcels were added or subtracted depending on the hereditary divisions, purchases, sales and their use as pledges for loans. In turn, both the land and credit markets benefited from the great autonomy with which peasants could dispose of land and from the factors that forced them to sell or mortgage it.Footnote 20

The legal framework regulating access to and ownership of land, contained in the kingdom's legal code, the Furs de València,Footnote 21 in turn facilitated access to and the wide spread of credit. Credit was as omnipresent in Valencian society and its economy as it was in the documentary sources. It appeared constantly in normative texts – theological treatises and ecclesiastical provisions, royal and municipal laws and ordinances – that condemned and prohibited usury, discussed the legality of the sale of rents (annuities) and regulated its operation. It also featured in fiscal sources, particularly wealth registers, since the receipt of rents – understood as another component of the taxpayer's assets – was subject to taxation. But without a doubt the two sources that best reflect and attest to the economic and social importance of credit are notarial and court records. They are very abundant for the fifteenth century, but for some localities, including the city of Valencia, the surviving series date back to the second half of the thirteenth century. The type of information they contain is different, because while notarial documents are records of the contracting of debt – in the form of loans at interest, rent sales and many other types of credit – the judicial registers record not only the debt, but also arrears and default, as well as the prosecution and penalisation of the latter. In other words, the lender and the borrower could go to the notary or the judge to declare, authenticate and document the debt in writing. In general, the most important loans, and especially the sale of rents (censals and violaris), which required many safeguard clauses, were formalised by notaries,Footnote 22 while those of smaller amounts – mostly instalment purchases, never the sale of rents – were declared before the judge and recorded in the court books.Footnote 23 However, regardless of where the debt had been declared and recorded, whether before the notary or before the judge, complaints over arrears and all actions aimed at forcing the debtor to settle the debt or offer his own assets – movable property or real estate – for sale at public auction, and with the amount of the sale to satisfy the creditor and cover the legal costs, were made in court and were recorded in the judicial books.

Short-term credit – notably, but not only, loans at interest granted by Jewish moneylenders – has been studied for many years from both notarial and judicial documentation,Footnote 24 as have also the origins and formation of the long-term credit market, from notarial sources focusing mainly on the city of Valencia.Footnote 25 On the contrary, the prosecution and punishment of arrears, which can only be examined from the judicial records, has to date barely been addressed: just one study of a rural community at the end of the fifteenth century, carried out by a team of which I was a member and published almost thirty years ago.Footnote 26 In this paper, I have directed my attention primarily to the notarial and judicial records of three localities: the city of Valencia, whose fertile countryside (the huerta, irrigated land) was strongly subject to urban influence,Footnote 27 and especially the towns of Cocentaina and Alcoi, more rural in nature, although with a large population working in manufacturing and non-agricultural activities. The oldest documents, from the second half of the thirteenth century, have recently been published,Footnote 28 while those from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are still unpublished and have been consulted directly in the Archive of the Kingdom of Valencia and in the Municipal Archives of Alcoi and Cocentaina.Footnote 29 In the case of the latter, the continuity of the series throughout the last two and a half centuries of the Middle Ages is admirable and seven moments in time have been examined (1304, 1342, 1372, 1433, 1451, 1476 and 1490). All of them have allowed to me gather a sample consisting of 4,071 documents.

3. Short-term and long-term credit and indebtedness

Both notarial and judicial records show that during the second half of the thirteenth and the early decades of the fourteenth century, short-term credit was the only form of credit available, coexisting thereafter with long-term credit based on the sale of rents. In the former case, it took the form of debt recognitions in the notarial records, and of payment obligations in the court books. That is to say, the debtor acknowledged that he owed a certain amount (in cash or in kind) to the creditor in a document formalised by a notary, or he ‘obliged’ himself, before the judge, to pay a certain amount to the creditor.

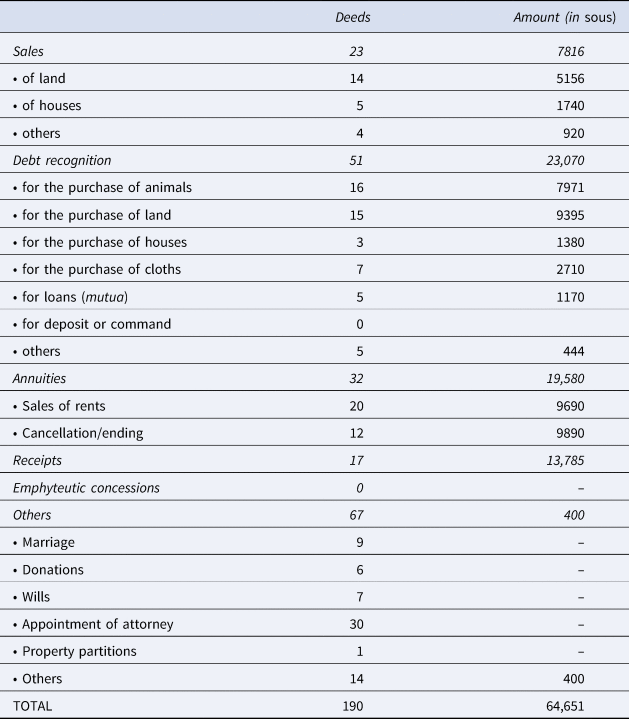

Let us start with the notarial documentation, the forms of credit that can be found in it and the importance that credit operations had in the set of transactions formalised before a notary. Between 1296 and 1303 the notary of Alcoi Pere Miró drew up between 136 and 190 deeds each year. In total, about 900 deeds exist from this period, which were recorded in the only book surviving from the thirteenth century.Footnote 30 As we can see in Table 1, the weight of credit and debt is absolute, in both numerical terms (the number of deeds) and in monetary terms (the volume of operations in cash). Five main types of deeds can be distinguished: sales, debt recognitions, receipts, emphyteutic grants and a miscellaneous one that includes all the other types of deeds. In turn, sales can be of land, houses, crops, seeds, animals and slaves, which, except in the first two cases, I have grouped together generically as “Others.” Debt recognitions include credit operations contracted to finance the purchase of animals, land, houses, cloths, cereals or wine, as well as cash (mutua) and in-kind loans and deposits or commands. Receipts and emphyteutic grants are sections without internal subdivisions and “Others” comprises all the remaining types, from marriage contracts and wills to donations (propter nuptias or inter vivos), property partitions, appointment of attorneys, work and apprenticeship contracts, arbitration awards, exchanges, leases, animal sharecropping contracts, and so on.

Table 1. Deeds recorded by the notary of Alcoi Pere Miró between 1296 and 1303

All bullet-pointed rows are sub-totals.

With 230 deeds, debt recognitions constitute the most important section in numerical terms and the second in monetary value, behind sales.Footnote 31 This is due to the large number of sales in one single year, 1297, which doubles that of debt recognitions, but in all the other years the volumes are very similar, with debt recognition sometimes higher. In reality, however, credit and indebtedness occupy a more prominent place, insofar as they are not limited to debt recognitions, but they also extend to the two other large sections, sales and receipts. Indeed, sales are rarely paid for in cash at the time the transaction occurs; they are financed by debt recognition deeds, formalised on the same day as the sale is made. In a first document, the buyer purchases a plot of land, a house or any other good from the seller, and immediately afterwards a second document is drawn up in which the buyer acknowledges that he owes the seller the amount of the price of the good sold and agrees to pay it, in one or more specific periods. Sales and debt recognitions are thus closely linked, as are receipts (àpoques), since in most cases they are payment recognitions, that is, of having received the amount owed. It could then be said that most deeds (569 out of 892) and, above all, the vast majority of the economic volume registered in them (87,249 out of 89,243 sous) are related to credit operations, while the rest of the contracts occupy a very secondary place. In other words, people went to the notary primarily to record loans and debts in writing, and only secondarily to formalise a wide variety of other activities in economic and social life: wills, marriage contracts, work and apprenticeship contracts. In the six years of the Alcoi registry, for example, 46 marriages and 36 wills were recorded, compared to 230 debt recognitions and 569 deeds related in some way to credit and debt.

Table 1 also allows us to see that most of the debts contracted before a notary were related to the purchase of real estate or operations of a certain economic volume, while, as we will see later, the debts declared before the judge (Obligacions) were for minor transactions. In any case, there were also forms of credit (loans, deposits, acknowledgments of debt for the purchase of animals, food, seeds and others) registered either before a notary or in court.

Two hundred years later, although the types of notarial deeds were still very similar, things had changed substantially with regard to credit, as can be seen in Table 2, which shows the results obtained for 1470. If we start with the similarities, we can see that the fifteenth-century record contains the same number of deeds as the more extensive one from the late thirteenth century (190 in 1297) and that the internal structure is practically the same. On the other hand, the weight of each of the sections has varied significantly; some have disappeared and others have appeared. Emphyteutic grants have disappeared, there being none in 1470, and within debt recognitions deposits and commands have disappeared. We find instead long-term credit, in the form of sales of rents or annuities, which was not yet present in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. By the late fifteenth century, however, they constituted one of the most important sections of notarial records. In 1470 sales (of land, houses, etc.), which in 1296–1302 accounted for 24.2 per cent of deeds, had fallen to just half, 12.1 per cent, while the section “Others” rose from 22.8 per cent to 35 per cent. However, what is truly relevant is that credit represented most of the deeds formalised before the notary, both directly (52.6 per cent) and indirectly (64.7 per cent, also including sales).

Table 2. Typology of notarial deeds, Alcoi 1470

Source: Arxiu Municipal d'Alcoi, 1470, sign. XV.1

All bullet-pointed rows are sub-totals.

In both the late thirteenth and late fifteenth centuries, credit – with its corollary, debt – was the main reason why peasants went to the notary. I say peasants because most of the actors in these deeds are explicitly referred to as such (agricultor in Latin, llaurador in Catalan) by the documents. They were going to buy and sell – land, houses, animals, grain, wine, cloth, etc. – but above all to finance these purchases with credit. The difference is that in the thirteenth century they did so through debt recognitions, while in the fifteenth century, even when debt recognitions were still important (the most important, in fact, in numerical terms and in monetary volume) debtors also resorted in significant numbers to the sale of annuities as a financial instrument. By this date, the sale of rents was already a fully consolidated form of credit and in Table 2 we can see that the monetary volume of new sales (carregaments, 9,690 sous) was very similar to that of cancellations (quitaments, 9,890).

The notarial records of Alcoi, a town with a marked presence of peasants among its population and with some 346 hearths (about 1,500 inhabitants) in 1469, have enabled us to verify the overwhelming weight of credit and indebtedness in all the transactions carried out before the notary. The obligations declared before the judge only contain credit operations, but they provide us with a complementary view, insofar as they record minor transactions – they do not include the sale of annuities – for which it was not worth going to the notary. If at the top of the pyramid of formal credit we find debt recognitions, deposits and sales of rents, all of them registered by the notary, at the bottom we find the obligations declared in court, with a predominance of instalment purchases, certainly the most widespread form of credit, although for smaller amounts.Footnote 32 The main difference between the debts declared before the notary (debt recognitions) and before the judge (obligations) seems to lie fundamentally in the volume and legal complexity of the operation. Commonly, debt recognitions used to accompany a previous purchase document. People went to the notary to buy – and formalise the purchase in writing – a plot of land, a house or any other good and instead of paying for it immediately in cash they financed it with an acknowledgment of debt. On the contrary, obligations were made for minor transactions, which had not entailed any prior documents, nor required many legal clauses.

For obligations we use the judicial records of Cocentaina, a town seven kilometres from Alcoi – where no judicial documentation has survived – with very similar characteristics and population (some 500 hearths), although with a greater presence of artisans. As I said earlier, I have used seven books from the court of Cocentaina, corresponding to the years 1304, 1342, 1372, 1433, 1451, 1476 and 1490, in order to analyse not only the structure of rural credit, but also its evolution in the last 200 years of the Middle Ages.

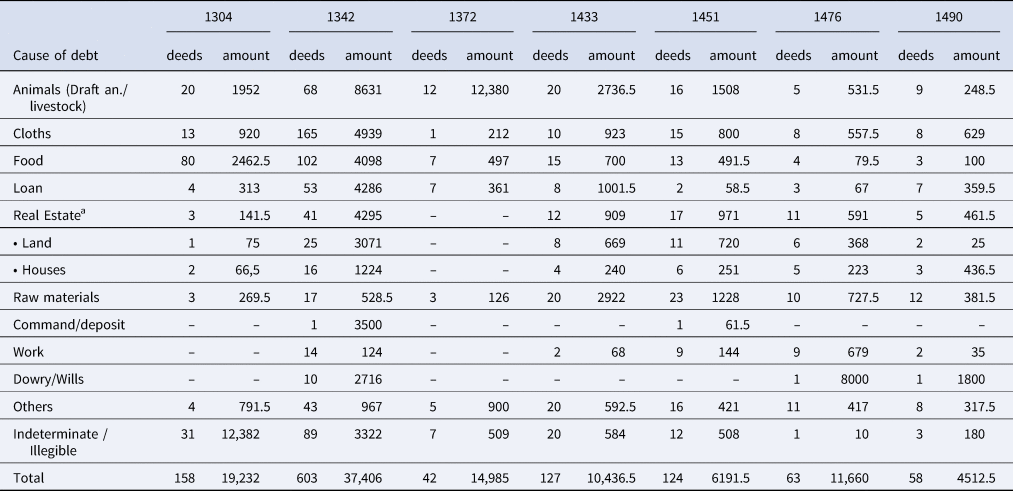

Table 3 shows the number of deeds and the volume of money that they represented in these seven sample years. Although, in the perspective of the series the year 1342, with 603 deeds, seems to be an exception, the number of judicial obligations and sentences, high in the first half of the fourteenth century, fell continuously in the following decades (127 and 124 in 1433 and 1451, respectively, and less than half of that, about 60, in 1476 and 1490). The volume of money that these operations represented also fell, from an average of around 20,000 sous in the fourteenth century to around 10,000 in the fifteenth century. We can go a little further, adding the debt declared before the notary to that declared before the judge. It is true that the data correspond to two different localities, Alcoi and Cocentaina, respectively, but it is also true that they are very close to one another, they are quite similar, and the total sum will in any case offer us a minimum amount. Between 1296 and 1302 the annual debt registered in notarial deeds was between 5,500 and 6,000 sous, if we limit ourselves only to debt recognitions, and between 8,500 and 9,000 if we also add settlements/receipts (àpoques); at the same time (1304), the obligations before the judge amounted to 19,232 sous. In total, then, in the early years of the fourteenth century, annual private debt was somewhere in the region of 28,000-29,000 sous. Almost two centuries later (1470 for the debt registered by the notary in Alcoi and 1476 for that recorded in the court books in Cocentaina), although there were fewer operations, the annual volume of debt was about 60,000 sous, of which 23,070 corresponded to debt recognitions, 13,785 to settlements/receipts, 19,580 to long-term annuities and 11,693 to obligations before the judge. Not only was the debt more than twice as high, despite the fact that the number of operations had fallen, but the number of debt recognitions and sales of rents (annuities) had increased, while the number of obligations had decreased. In other words, the volume of the debt had increased in nominal terms and people preferred to register it before the notary rather than before the judge. This is also in line with the increasingly widespread type of debt: long-term annuities and for significantly higher amounts.Footnote 33

Table 3. Credit and debt before the judge. Obligations in Cocentaina

Source: Arxiu Municipal de Cocentaina, Cort del Justícia, sign. 3/1, 8/2, 14, 31/11, 38/1, 46/1 and 51. The archival series includes not only obligations but also sentences. In fact it is called Libre de obligacions e condempnacions.

On the other hand, we can get an idea of what this volume of annual debt meant and what impact it could have had on the population. In the second half of the fifteenth century, Cocentaina, a medium-sized town with a strong manufacturing base, had about 600 hearthsFootnote 34 (approximately 3,000 people), so that annual total debt of around 60,000 sous represented an average of 100 sous per household, a more than plausible amount considering that it included all types of debt, both short-term, for instalment purchases or consumer loans, and long-term, linked mainly to the sale of annuities. It is possible to closely study the type of debt contracted and the respective percentage of each one. We have already seen in Tables 1 and 2 what the dominant types were in the notarial records, and how long-term credit (annuities) had been growing until it almost equalled short-term loans. Table 4 shows the causes of the debts declared before the judge in the six sample years that we have analysed.

Table 4. Cause of debt in Cocentaina's Obligations

Source: Arxiu Municipal de Cocentaina, Cort del Justícia, sign. 3/1, 8/2, 14 m 31/11, 38/1, 46/1 and 51. Indeterminate/illegible refer to deeds that do not specify the cause of the debt or that are illegible due to the poor condition of the document.

a The rows ‘Land’ and ‘Houses’ are sub-totals of ‘real estate’.

In practically every sample year, the purchase of animals is the main reason why people get into debt. It accounts for 82.6 per cent of the volume of all operations in 1372, almost half in 1304 and more than a quarter in 1342 and 1433, at which point its importance begins to wane, although it never ceases to be an important chapter. It was not only a market of high economic value but also a highly specialised one, in which we can distinguish between draught animals, on the one hand, and livestock, on the other. Donkeys and mules predominated among the former, but sales also included oxen and nags. The Muslims in the region (from Fraga, Muro and other hamlets and villages near the town) were particularly active in this market; they came to Cocentaina to sell the animals that they had reared to Christian buyers (from Alcoi or from Cocentaina itself and other Christian population centres). In turn, they bought cattle and, above all, cloth. Livestock sales were dominated by sheep and rams, sometimes imported from Castile, in numbers that amounted to several hundred a year, followed by goats and to a lesser extent cows and pigs. In 1342, for example, 221 sheep and 108 rams brought from Montalbanejo, a hamlet near Cuenca, were sold in five operations, staggered between 6 and 24 November, purchased by Christian and Muslim buyers from Penàguila and other villages in the Cocentaina area, for a total value of 1,560 sous. These purchases were not paid for in cash. In one case the payment of half was stipulated within 16 days and the other half at the next Carnival festival, about two months later; in another case, the full payment was also deferred to Carnival, and in another two, to Easter, more than four months later. As the deadlines were not met, the sellers reported the delay to the judge (28 April), but the debts were eventually paid (on 11 July and 18, 20 and 21 November, respectively), just one year after being contracted and registered in the court records of Cocentaina. Sheep were particularly valued in a manufacturing region like Cocentaina because the animals provided meat and especially wool for the local textile industry.Footnote 35

In the debt obligations declared before the court of Cocentaina, cloth purchases come next after animals. Their economic importance stands out, together with that of the acquisition of raw materials, from the middle decades of the fourteenth century onwards. This is not surprising, since Cocentaina was an important manufacturing nucleus in the centre of an industrial region. In 1304 cloth occupies a modest position, but by 1342 its importance has begun to be noted; it has risen to more than 50 per cent of the sales of animals, and it even overtakes them in the last quarter of the fifteenth century (1476 and 1490). People from all over the region (Agres, Alcoi, Alcolea, Benifallim, Benilloba, Castalla, Gorga, Onil, Pego, Penàguila, Seta and Xixona) flocked to Cocentaina to buy cloths. The vendors were usually cloth merchants (drapers) from Cocentaina or from the relatively nearby city of Xàtiva, the second largest urban centre in the kingdom after the capital Valencia. The amounts purchased were not usually very high, so they were clearly for the members of the buyer's family, although in other cases the buyers were also artisans working in the textile industry (weavers, carders, cloth shearers dyers), and purchases were not concentrated in one specific period, but were staggered throughout the year. As for raw materials, the importance of which continued to increase throughout the period, they included products such as wool, mulberry leaves (for silkworms), dyes, woad, saffron, rose madder, skins, hides, wax, lime and wood, necessary for both textile manufacturing and the construction industry.

Three items followed, whose importance in monetary volume was very similar, although it varied depending on the years: purchases of real estate, purchases of food and loans at interest. In the first case, they were purchases of land houses that were not paid for on the spot but the total amount was divided into various instalments or deferred for several months. Real estate transactions were not usually declared before the judge, since they were mainly registered by the notary, but they were still present and constituted an important part of the obligations in the court in Cocentaina. In any case, although obligations may not be the most appropriate source for studying the land market, they are for studying indebtedness and arrears in property and land transactions. Regarding food purchases, in only a few cases were they of seeds for the next sowing and in general it was food for consumption in the lean season, or ‘hungry gap’ (the period between one harvest and the next). It was mostly wheat and other minor cereals (barley, millet, oats, spelt and fodder), as well as olive oil, wine, meat, sardines and figs, a fruit highly appreciated, especially by the Muslim population. In many cases, the date stipulated to make the payment was 24 June, Saint John's Day, coinciding with harvest time. Three types of food transactions can be distinguished: purchases in instalments or with deferred payment; loans in kind; and anticipated harvest purchases, in which the buyer insured the crop produce, although payment for it would not be made until the moment the produce was harvested and delivered. Finally, the loans (mutua) are loans at interest, although this is only made explicit in the case of Jewish moneylenders, whose legal interest rate was set at 20 per cent, whereas when it came to Christian lenders, it was declared that there was no manifest usury in the loan (sine usura ficta aut manifesta), which is hardly credible. Table 4 shows that the loan at interest was important in economic terms, but it was far from being the main source of credit (in 1342 it represented 11.5 per cent of the total amounts borrowed or owed, but in all other years it was below 5 per cent). The radius of action for loans was considerably expanded and extended to more remote locations – and in the case of the last three, large urban centres – such as Vila-Joiosa, Alicante, Xàtiva and Valencia, between 40 and 100 kilometres away. The table also shows the scant importance in numerical terms of other forms of credit, such as the command or deposit, among the obligations declared before the judge – only two in our sample, but the first of them, in 1342, was for a really high amount (3,500 sous). Most likely, this type of credit would be formalised mainly before the notary, and hence its negligible presence in court records.

The same would probably be the case with the debts derived from the payment of the dowry, its restitution – in the event of the husband's death –, or the legacies left by the testator in his will. In our sample there are hardly any, barely a dozen deeds, although for very high amounts (8,000 sous in 1476 for the restitution of a single dowry, when none of the other items exceeds 600 sous, and another case also of a dowry in 1490 worth 1,800 sous).Footnote 36 A penultimate chapter worth singling out, although not very important in aggregate economic terms, was debts due to unpaid wages. In general, the people affected were women who had worked as maids or domestics, or even breastfeeding babies or young infants, and whose employers had not yet paid them, but also of agricultural or even handicraft tasks pending payment. The debtors were therefore not poor peasants or craftsmen but well-off farmers, artisans, merchants, or notaries and other urban professionals in this case.

The generic concept of Others includes all other debts, of a very varied nature, but whose smaller numerical and economic importance makes it advisable to group them together as a single item in the table and, in any case, to briefly list them here. This varied group comprises such diverse and heterogeneous concepts as the delays in the payment of ecclesiastical tithes and first fruits; the leasing of mills, oil presses and ovens; the legal advice provided by lawyers and notaries; burials, funerals, and Masses celebrated for the souls of close relatives; clothes (doublets, shawls, gonella, gramalla, drawers, shoes, espadrilles, hats); bed linen; furniture; containers (jars, jugs); weapons (spears, swords, crossbows); saddles; looms; parchments; grocery items; hostel accommodation; the partition of property; the provision of nourishment for minors; and even a notary's salary for teaching an adolescent to read and write. Finally, a last section in the table, Indeterminate/illegible, includes the deeds that do not specify the reason for the debt, but the amount owed, and those that could not be read due to the state of conservation of the document.

Although it is not possible, for reasons of space, to analyse this sample – which includes more than 1,200 deeds – in greater detail in this article, we can draw some important conclusions about the type of credit and debt that was registered in the court records. In the first place, rural credit was for investment rather than for consumption. Even including all food purchases in the latter (wheat and other cereals, wine, oil and fruit), which would not be entirely correct because some of these purchases were speculative or intended for subsequent sale, this would not represent a really significant percentage, since, depending on the year of the sample, it was less than 10 per cent and even 1 per cent. In addition, if the purchase of cloths were also included in consumer credit, the total would not exceed 20 per cent. This means that the vast majority of the credit was destined for investment. People got into debt to procure animals – draught, for agricultural work and transportation, and livestock to sell as meat, hides and wool – and not just to buy them, because there are examples of the temporary rental of mules. They also sought land and houses, raw materials and even work equipment such as looms. Second, most of the buyers/debtors were peasants from the villages and hamlets in the region, including those from Muslim communities, while the sellers/creditors were mainly concentrated in the towns, where businessmen, cloth merchants, notaries and also Jews lived. And third, the predominant form of credit was not loans or commands/deposits – even if the value of just one of the latter could far exceed the sum of other types – but purchases in instalments or deferred payment. Credit contributed powerfully to running and lubricating the economy of this region, both agricultural and manufacturing, with large amounts of money – around 60,000 sous a year, if we add the obligations before the judge and the debt recognitions and annuities formalised by the notaries. But it did so more through purchases in instalments or with deferred payment, legally expressed as debt recognitions (before the notary) and payment obligations (before the judge), rather than through formal credit instruments.

4. Deadlines, arrears and auction sales of debtors’ assets

In both cases, the buyers/debtors were obliged to pay the debt within a stipulated period. How long was this? Days, weeks, months, years? Did it coincide with a certain date in the religious or agricultural calendar? What would happen if, when the deadline arrived, the debtor did not pay? Can we measure the time that elapsed between the fixed term and the time of payment? How long had it been since the breach of the deadline and the seizure of the debtor's assets? The deadline stipulated in obligations for the payment of debts was most commonly established as ten days, which could be increased to one or two months or even longer, if the debtor offered a guarantor (fermança), who, with his assets, was equally obligated to pay the debt. In a few cases no date was set for payment, but it was left to the discretion of the creditor, who could demand it at any time. Tables 5 and 6 show the dates that were used as deadlines, with the payment periods expressed in days, months and years. The cases grouped under the heading Indeterminate had no date or were illegible.

Table 5. Dates and periods set as deadlines for obligations in Cocentaina

Source: Arxiu Municipal de Cocentaina, Cort del Justícia, sign. 3/1, 8/2, 14, 31/11 and 38/1. Other includes different combinations such as Easter and St. Mary of August, Easter and Christmas, Saint John and St. Mary of August, half in each instalment. The results for 1476 and 1490 are not included in this table because deadlines are only specified in three cases (Saint John, St. Mary of August and Christmas) and because only the initial 10-day deadline is indicated, respectively.

Debtors and creditors resorted to the religious and agricultural calendars to set the deadline for the payment of the debt. Three dates stand out above all the others, linked to three religious festivals: Saint John (June 24), St. Mary of August (August 15) and Saint Michael (September 29), followed at a great distance by Easter and Christmas. These three dates were linked to the times when winter cereals, grapes and spring cereals were respectively harvested. Throughout the year, people bought the products they needed – food, clothing, land, houses, raw materials, work tools, etc. – but they did not pay for them on the spot. Instead, they divided their payment into various instalments or they deferred it to harvest time, when they thought they would have cash. In the fourteenth century the most important payment dates were Saint John and St. Mary of August, especially the latter, which in 1342 was stipulated more than twice as many times as the former, but Table 5 shows that many more festivals during the year were used, from Carnival to Christmas. In the fifteenth century, festivals were no longer used so much; the deadline for most obligations was 10 days, perhaps because the greater importance of manufacturing in the region meant that deadlines no longer had to be set according to the agricultural calendar.

As for the length of obligations, a clear fact emerges: they are short-term debts. Very few last beyond a year and the vast majority are granted for less than half a year. In some cases, there is no specific deadline for payment; it is left to the discretion of the creditor, who can demand it whenever he wants, and in many others, as we see in the table, the deadline does not appear either. But in all the cases where a payment date is stipulated, which is most common, in the great majority it is less than three months and even just ten days, the usual term in 1342 and in the second half of the fifteenth century. It should be emphasised here that the obligations generally correspond to instalment purchases, and for these, even if payment is in instalments or deferred, the term rarely exceeds six months (although in 1342, an exceptional year with regard to the number of obligations, more than 130 cases are recorded).

When the deadline expired, if the payment had been made, the creditor stated that he was satisfied and the debt was cancelled. Otherwise, non-payment was reported to the judge, whether it was obligations or acknowledgments of debt before the notary. In his claim (reclam) the creditor urged the judge to take legal action against the debtor, that is, to send him a manament executori ordering him to pay the debt or offer movable or immovable property with which to settle it within ten days. In cases where there is no claim or acknowledgment of the debt being paid, it can be assumed that there was an out-of-court settlement between the parties, and in fact there is an explicit case in which the creditor withdraws his complaint stating that he has reached an agreement with the debtor.

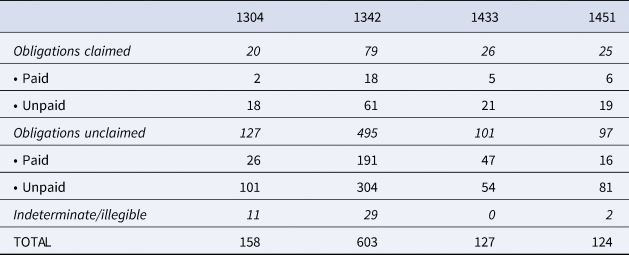

Table 7 shows that in the vast majority of obligations in Cocentaina no claim was made, although there is no evidence that they were paid: 63.9 per cent in 1304, 50.4 per cent in 1342, 42.5 per cent in 1433, and 65 per cent in 1451. And if those where a claim was made but it was not paid are added, the percentage is truly staggering: 75.3 per cent, 60.5 per cent, 59 per cent and 80.6 per cent, respectively. Apparently, then, a majority of the debts declared before the judge were never settled. Not even all those that were claimed before the judge were. There must therefore have been some form of out-of-court agreement, of negotiations between the creditor and the debtor to settle the dispute privately, because otherwise it is impossible to understand how the system could continue to function, and that during the two centuries examined here buyers and sellers came before the judge to register debts and debtor's obligations to pay them. However, quite a large number of debtors did end up paying the amount owed, either before or after the creditor made his claim: 17.7 per cent in 1304, 34.6 per cent in 1342, 41 per cent in 1433 and 17.7 per cent in 1451. They are the ones whose obligations appear explicitly cancelled.

Table 7. Claims and cancellations of obligations in Cocentaina

Source: Arxiu Municipal de Cocentaina, Cort del Justícia, sign. 3/1, 8/2, 31/11 and 38/1. The data for 1476 and 1490 have not been included because they hardly contain references to claims and debt cancellations.

Finally, if the debtor had still not paid the debt after the claim was made, the judge ordered the court broker to auction off the debtor's assets for a period of ten days, if it was personal property, or 30, if it was real estate. Table 8 shows all the cases of judicial sales by public auction in Alcoi (19 cases in 1264), Cocentaina (113 cases between 1269-1295) and Valencia (815 cases between 1282-1287).

Table 8. Judicial sales due to debts in the 13th century

Source: See note 28. *These 53 cases are made up of 38 sales of debts and censuses, 6 of slaves and 9 of a generic nature.

In Alcoi and Cocentaina, the two smaller towns, land figured highly in judicial public actions, but it was not so important in the city of Valencia, where it was exceeded by sales of houses and above all clothes. As we have already seen, most of the debts were due to instalment purchases and other forms of short-term credit, even very short term (less than six and less than three months), in which land was rarely used as collateral. In the event of non-payment, the lender kept the goods that the debtor had pawned or those he had assigned to be sold by the court and thus pay the creditor. Lenders could be either Jews or Christians. They were not generally interested in land and real estate, but they were in furniture, jewellery, clothing, animals and weapons, which is shown in Table 8. Borrowers could seek credit for consumption or investment (more for the latter than the former, as we have seen), but what is clear is that lenders did not seek land. Many of the loans were not guaranteed by any particular pledge, but by the general obligation of the debtor's assets or those of his guarantors (fideiussores). When a pledge is indicated, it is usually an animal or a part of the crop for small amounts or a house or jewellery for large sums. However, as stated, these pledges (penyores) were seldom required. García Marsilla only finds them in 23 out of a total of 566 loans in 1298-1350,Footnote 37 something, in his opinion, indicative of a fairly fluid capital market, in which there was already enough confidence in the fulfilment of contracts to make these practices unnecessary.Footnote 38 In any case, whether the loan contract included a pledge or not, default entailed the confiscation and sale of the debtor's assets. As has been studied by Angelina García, in the event of non-payment, Jews who lent money to the peasants in the countryside around Valencia in the first half of the fourteenth century mostly obtained agricultural harvests, from wine and raisins to wheat, dried fruit, almonds, figs and, much more expensive on the market, saffron and sugar.Footnote 39 If there was any kind of strategy in rural credit, it was certainly not so much one of territorial conquest as of the appropriation and commercialisation of crops. Credit and the purchase of harvests are in fact two sides of the same coin: the penetration of urban – Jewish in this case – capital in the countryside surrounding the city. Together with them, the other goods appropriated by creditors or confiscated and sold judicially to settle debts coincide with those found by myself in the judicial records and systematised in Table 8: clothing, work equipment, animals, weapons and jewelry.

Even if they had not been used as collateral, the judicial sale of land and houses was also a resource used to settle outstanding debts. In the records of the court of Valencia it gave rise to a specific series called Major Sales (Vendes majors). In just three months, from June to August 1353, some 40 cases were conducted in which houses and land were sold by order of the judge at the request of the creditors. In total, 15 parcels of land (worth more than 4,000 sous), 14 houses and 6 personal assets (including money and rents) were auctioned, while in four other cases the file is not clear.Footnote 40 Of all of them, in only three cases was the buyer the creditor himself, so no strategy of territorial appropriation by lenders can be deduced from these judicial sales. The debtors offered their lands to be sold, and to settle the debt with the amount of the sale, but they could have offered other assets, both movable and immovable, and in fact some did.

The importance of collateral, and particularly land, increased with the expansion of long-term credit. Although the first manifestations of this type of credit, in the form of sales of annuities, date from the last decades of the thirteenth century,Footnote 41 in reality it did not become widespread until after the 1370s. García Marsilla documents only 18 annuities for the decade 1351–1360, 27 for 1361–1370, 167 for 1371–1380 and 321 for 1381–1390. As for claims for non-payment presented before the judge (justícia civil) of Valencia between 1361 and 1372, 104 were against defaulters on Jewish loans, 11 for life rents (violaris) and four for perpetual rents (censals).Footnote 42 By the second half of the fifteenth century, the sale of annuities had become one of the main forms of credit, although not the only, or the majority, one. In Alcoi, as we have already seen (Table 2), the monetary volume of the annuities registered by the notary in 1470, 19,580 sous, was close to that of all other forms of credit (loans, debt recognitions, etc.), 23,070 sous. The proportion is slightly lower in nearby Cocentaina in that year, analysed in this case through judicial documentation. Of the 208 manaments executoris activated by the judge against debtors in 1470 (Table 9) and registered in the court books, 68 corresponded to claims for unpaid annuities and 140 for other types of outstanding debts (for the purchase of animals, food, houses, land, loans and other unspecified obligations) – equivalent in monetary value to 7,337 and 20,275 sous, respectively – for a total amount of 27,612 sous.Footnote 43 In other words, long-term credit, the most formalised type of credit and the one for which land could be used as collateral, occupied an important place in the second half of the fifteenth century, but it was far from predominant, surpassed by instalment purchases and other forms of short-term credit.

Table 9. Execution orders sent by or to the Justícia of Cocentaina (1470)

Source: Arxiu Municipal de Cocentaina, Cort del Justícia, 44 (1470). See note 43.

As we can see, the security of the annuities was also guaranteed, as in the case of loans, obligations and debt acknowledgments, by the judicial machinery. When the debtor delayed payment of rents, the creditor, personally or through a prosecutor, appeared before the court, showed the judge the original document of the debt and required that the debtor in arrears be ordered to pay. If the plaintiff resided in a location other than the debtor's, his claim was transmitted by the judge of one town or village to his counterpart in the other one, urging him to take the necessary steps. In all cases, these began with the judicial officer (agutzil or saig), going to the debtor's house in order to notify him of the execution order (manament executori) enforced against him. In this order, the debtor was urged to pay the amounts claimed within ten days, as well as the penalties and expenses and court costs incurred during the legal proceedings. After ten days, if the debtor had not paid, the creditor went back to the court, requesting that the debtor's assets be valued, in order to be able to recover the amount owed. Then the court officials went to the debtor's house to make an inventory of any goods that could be found there, usually animals and household furniture. An estimate was then made of the possessions seized and a caplleuta (the man charged with looking after the debtor's seized possessions), generally a neighbour, a relative or even the debtor himself, was appointed to keep them intact and in good condition until the time of the auction. Only if the movable property was not enough to satisfy the debt, the penalties and the court costs, did the judge also proceed to seize the immovables: defaulter's houses and land.Footnote 44 Of the 208 execution orders issued by the justice of Cocentaina – 74 through Lletres and 134 through Manaments executoris – in 1470 only seven ended with the seizure and sale at judicial auction of real estate (four houses and three plots of land).Footnote 45 In the vast majority of cases the property seized was chattels and animals: mules, chests, beds, mattresses, bed sheets, blankets, clothing, and even a steel crossbow.Footnote 46

The most dramatic outcome for peasant families was unquestionably the confiscation of their property and assets. As has been said, the first thing to be seized were the goods the peasant needed the most to work his land, the draught animals: oxen, horses, mares, donkeys and mules. Dispossessed of part of his means of production, and with the maintenance of the family economy in danger, the defaulter had no choice but to resort to credit again, which plunged him even further into debt. If the debtor had no animals, or these were insufficient to satisfy the debt, the judge's attention was directed towards the furniture in the house. The description of this tells us about the objects typically found in the home and gives an idea of the material living conditions of peasants in Valencia, especially the poorest of them. The first to be seized were the items of furniture in the bedroom (the bed and the bedding) and those in the dining room (tables, benches and rugs) and the kitchen (bowls, dishes, boilers, pans and containers). Finally, in the barn and in the yard, the authorities seized all the agricultural implements, work tools, and even weapons (spears, swords, shields and helmets). Any crops or reserves of food that might have been stored in the house were also confiscated, and sometimes the creditor even asked for the sequestration of the crops still in the ground. Once the deadline had expired – 30 days according to the law, plus another ten days of grace, during which time the confiscated assets were held by the caplleuta – the court broker proceeded to their public auction.

The purpose of the judicial sale by way of a public auction was to obtain a price equivalent to the amount claimed, plus the fine and court costs.Footnote 47 After the auction, the buyer had ten days to pay the amount he had bid, while the debtor was given five days to assess the court costs, which had to be paid along with the debt and the penalty, on top of the sale price. If more money was obtained for the goods, the difference was restored to the defaulter. That, however, did not occur very frequently. In fact, a fair price for the auctioned goods was not always found, nor did all auctions find bidders. In 1511, for example, the judge of Sueca, a town 30 kilometres south of Valencia, apologised to the governor for failing to collect the amount claimed, alleging that he had confiscated the debtor's assets and had auctioned them publicly, but there had been no bidders, since ‘it is customary in Sueca for nobody to buy anything through the court’. If no bidders could be found, the creditor himself could be forced to purchase the confiscated property, including the land, even if he was not interested in it. This was not necessarily advantageous for him. On the one hand, despite the advantage of buying land at a price below market rate, the profit made might not compensate for the value of the unpaid annuities. On the other hand, the purpose of lenders when extending credit was not to expropriate the debtor's land, but to make a profit in the case of a loan, close a deal in the case of an instalment purchase, and receive secure regular rents in the case of annuities.

Not all sales of land, including those forced by indebtedness, were conducted by judicial auction. Before this last resort, the debtor could try to sell the land himself on the market and obtain a better price. In 1452, to cancel certain amounts owed by his father – ad opus solvendi certas peccunie quantitates que per dictum quondam Antonium Nicolaum debebantur heredibus honorabilis dompne Damiate de Rexach, uxor quondam honorabilis Gilaberti de Rexach, militis, quondam, habitatoris civitatis Valencie, ratione possesionum et hereditatum infrascriptorum –, Joan Nicolau sold property consisting of five plots of land, purchased by Antoni Saurí for 800 sous. The cause of the debt was an annuity established by the deceased on these possessions, whose interest he could not pay. In other cases, the purpose of the sale was to cancel the rent, which required the loaned capital to be repaid. And so, to amortise an annuity of 3,000 sous of capital and 200 of interest (6.66 per cent), the debtor sold a farm in Foios to a third party, composed of domos, orto et VII cafiçatas et mediam (3.75 ha) of vineyard, for 3,000 sous, a sum that the buyer promised to pay within one year, assuming until then the interest payments.Footnote 48 All these sales shed light for us on the difficulties faced by peasants when repaying loans or continuing to pay the interest, something that compelled them inexorably to dispose of their possessions, alienated in favour of their creditors or third parties.

In any case, lenders did not seem to be interested in obtaining the lands of their debtors. In only three cases out of 208, as we have seen, did non-payment end with the judicial sale of the debtor's land, and in not one single case did it pass into the hands of the creditor, and when creditors did take possession of land for non-payment, they quickly sold it or granted it again in emphyteusis to other tenants. Take the case, for example, of the house and plot located in Massalfassar, 10 kilometres north of Valencia, that Bartomeu Vinader, a local peasant, sold in 1424 to the nobleman Jaume de Centelles, the direct lord of the land and at the same time the creditor of an annuity of 33 sous 4 diners established on the property, for the symbolic price of 5 sous. On the same day, the lord granted the same plot to a new tenant, Pasqual Carinyena, for an entry fee of 360 sous. To pay this fee, the new tenant did not disburse a sum in cash, but established, in favour of the lord, a new annuity that he secured on the parcel, for capital equivalent to the entry fee, and with a pension of 30 sous at a rate of 8.33 per cent.Footnote 49 The price of 5 sous of the first sale was clearly fictitious and masked the annuity established on the tenure. Most likely, the first tenant could not pay the rent, and was forced to sell the possession to the lord, who immediately transferred it to another tenant. It was not the lord's intention to expropriate his peasants, but to ensure the regular collection of rents, whether agrarian (emphyteutic) or established (censals). In fact, as shown in another study, lords and urban landowners took little part in the peasant land market, in which peasants played a prominent, preponderant place as sellers and buyers. On the contrary, nobles and ecclesiastical institutions, and even merchants and citizens, did not establish any monopolies in this market, nor were they in any way significant in it, thus ruling out any strategy of dispossession of the peasantry and territorial concentration in urban or aristocratic hands. The few lords who bought plots of land – nine in total – immediately granted them in emphyteusis. Both they and the urban lenders were after rents, not land. They did not set out to change the agrarian system, accumulating land to manage it directly, or lease it in the short term, but to ensure the regular receipt of rents.Footnote 50

5. Conclusion

The recourse to long-term credit, secured on the debtor's property, provided peasants with the financial means to make important payments or even to purchase land. However, the price to pay for this was getting into structural debt – rents differ from the loan precisely because they are long-term (life-time or perpetual) debts – and adding the regular payment of interests on debts to seigniorial exactions, ecclesiastical tithes and royal and municipal taxes. Non-payment of the debt could eventually entail the seizure of the land and its judicial sale at public auction. It was not land that creditors – noblemen, citizens, and also rich peasants – sought, and in fact there was no process of territorial accumulation and expropriation of the peasantry, but the regular secure rents that their credit investments yielded for them and in particular the annuities charged on peasant land.

Peasants got into debt, as we have seen, for many reasons. One of them, but not the only or the most important one, was in order to buy land. And they lost their property, mostly the movable assets and more rarely the real estate, to pay off the debt. Rural indebtedness was deeply and structurally rooted in the fragility of peasant economies and their precarious balance to ensure their reproduction, threatened by poor harvests, increased taxation and the small size of the holdings. Indebtedness and the land market were definitely interwoven, and many peasants sold their lands to pay their debts before the judicial machinery forced them to do so and the parcels were judicially auctioned off. Among other reasons, this may help us to understand the great dynamism of the peasant land market, and the incessant circulation of plots and debts recorded by the Valencian documentary sources in the final two centuries of the Middle Ages. What is clear in any case is that lords and urban landowners did not take advantage of this peasant indebtedness to take possession of the lands of their tenants or debtors and introduce profound changes in the management system, as was the case, for example, in northern and central Italy.

This may explain why the land market remained mostly the business of peasants and there was no real strategy of territorial conquest and expropriation of the peasantry. The lords, noblemen or bourgeois, immediately granted the plots they recovered in perpetual emphyteusis: their goal was not to accumulate land, but to ensure the collection of rents. The land market, even though it was very active and contributed to intensifying the inequalities among peasants, did not undermine the foundations of the agrarian system, based on the predominance of the small peasant holding and the constraints of the seigneurial exaction; on the contrary it guaranteed its stability and continuity after the Middle Ages.