Policy Significance Statement

This article provides policymakers with an understanding of what values-based policy communication is and how, using robust data, they can communicate policies that are concordant with the values of their audiences in a way likely to elicit sympathy. Although this article uses the example of migration policy communication, the same approach can be taken for policies on any politically controversial issue.

1 Introduction

What types of strategic communication messaging regarding migration policy are likely to be more or less effective? Studies of communication regarding migration have overwhelmingly focused on negative or unrepresentative portrayals of migrants by the media, which are argued to often be hyperbolic in order to garner additional readers or viewers, or by political actors using such frames for strategic electoral reasons (e.g., King and Wood, Reference King and Wood2001; Blassnig et al., Reference Blassnig, Engesser, Ernst and Esser2019). As such, academic research on migration communication has tended to be drawn from the fields of media studies or political science. Research considering when strategic communication for less, arguably, nefarious reasons is effective has been less developed. Despite that, or perhaps because of it, in recent years, a number of advocacy groups, NGOs, think tanks, and nonacademic research organizations have produced guides to communicating on immigration to host populations. Owing to their origin, either implicitly or explicitly these guides usually have had the aim of increasing the positivity to migrants or migration among the citizens and voters of host countries. For the same reason, they have typically been only partially rooted in robust or systematic scientific understandings of the relationship between types of communication and their effects on attitudes, though this does not necessarily reflect their credibility or usefulness.

This study places the most common recommendation from practitioners—that migration communication should be based on values—within the broader scientific literature by introducing Schwarz’s psychological theory of “basic human values” and then using European Social Survey data to visualize the relationship between these values and attitudes to immigration, a relationship already well established in the political psychology literature. It is argued that messaging with a value-basis that is concordant with that of its audience is more likely to elicit sympathy, whereas that which is discordant with the values of its audience is more likely to elicit antipathy. Given the value-balanced orientations of those in host populations with moderate attitudes to immigration—the so-called “moveable middle” that are the explicit target of many recent immigration messaging campaigns (e.g., ICPA (International Centre for Policy Advocacy), 2017; Carter, Reference Carter2018) based on segmentation analysis of attitudes, “anxieties” and socio-demographic determinants (e.g., More in Common, 2017)—persuasive migration messaging is theoretically most effective when taking a values-balanced approach. This notion of the “moveable middle” has been linked to Downs’ 1957 Median Voter Theorem (Hemphill and Shapiro, Reference Hemphill and Shapiro2019). As such, it should also attempt to mobilize values of its opposition; that is pro-migration messaging should mobilize Schwarz’s values of conformity, tradition, security, and power, whereas anti-migration messaging should mobilize values of universalism, benevolence, self-direction, and stimulation.

The article then moves on to considering migration communication campaigns from both sides of the Mediterranean as produced by NGOs and public policy makers. This inventory of migration communication campaigns was provided by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), an international organization of 17 member states devoted to research, projects, and activities on migration-related issues and to provide policy recommendations to the governmental agencies of states, as well as to external governmental and intergovernmental agencies and international organizations. It is then systematically considered how well these campaigns align with our expectations as derived from our theoretical framework and then shown that few pro-migration campaigns contained value-based messaging, whereas all anti-migration campaigns did. Similarly, very few pro-migration campaigns included values besides “universalism” and “benevolence,” whereas anti-migration campaigns included values associated with both pro- and anti-migration attitudes. Examples of each case are demonstrated before discussing ramifications for policy communication.

2 The Importance of Considering the Role of Values in Migration Communication

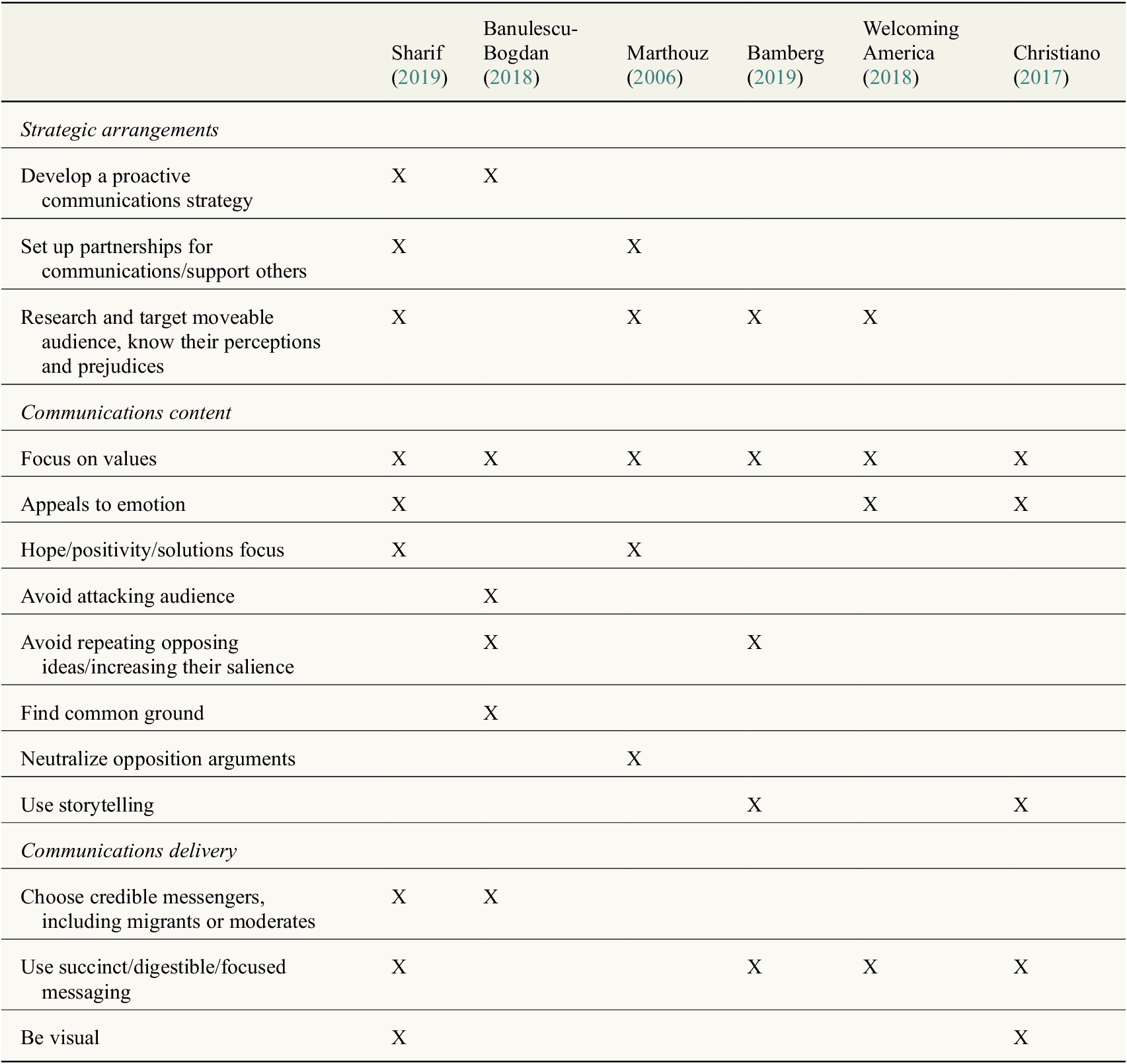

In this section, I show that so-called “best-practice guides” on migration communication by migration advocacy groups, think tanks, and research organization have continuously made reference to values in migration communication. Whereas there is a still relatively underdeveloped academic literature considering what types of migration communication are effective (however, for potentially relevant findings see Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2020; Walter et al., Reference Walter, Cohen, Holbert and Morag2019; Nelson and Garst, Reference Nelson and Garst2005; Bansark et al., Reference Bansark, Hainmueller and Hangartner2017; Carter, Reference Carter2018), the policymaker, or practitioner, literature has grown considerably recently. In recent years, a number of reports have been published that outline recommendations for how to effectively communicate on immigration issues in a way that might change the attitudes of host populations. In this section, I overview the findings of six of these reports, five of which were published since 2017. In Table 1, I synthesize these findings.

Table 1. Summary of key recommendations from existing best-practice guides for migration communication.

First, Sharif (Reference Sharif2019) suggests that “progressive communicators … to win the debate” in “Communicating effectively on migration”: (a) “develop a communications strategy and leadership”; (b) “choose credible messengers, including migrants”; (c) “apply value-based and emotive approaches”; (d) “lead with hope-based solutions”; (e) “be visual”; (f) “target a movable audience”, that is those with more moderate and less entrenched attitudes; and (g) “support fair reporting.” Second, Banulescu-Bogdan (Reference Banulescu-Bogdan2018) argues that recent technological, political, and media changes mean that an overabundance of “facts” has undermined their social credibility. The author proposes that those communicating on immigration: (a) note that “cost–benefit analyses may miss the point” since economics is only one value under consideration; (b) “avoid arguments that may be views as personal attacks”; (c) “give people a way out instead of trying to prove them wrong”; (d) “avoid repeating false ideas—even to debunk them”; (e) “engage credible messengers from across the aisle”; and (f) “start building a culture of critical thinking long before an election cycle or crisis.” Third, Marthouz (Reference Marthouz2006) offers an exhaustive list of recommendations, with examples, followed by seven “guiding principles”: (a) the importance of values rather than facts; (b) be aware of and work around popular prejudices; (c) starting from a position of common ground; (d) neutralize the opposition by undermining their arguments; (e) similarly, ignore or undermine the most hostile; (f) be solutions-oriented; and (g) coordinate with other NGOs.

Fourth, Bamberg (Reference Bamberg2019) makes six recommendations aimed at the European Commission, although useful for migration communicators generally: (a) avoid increasing the salience of migration; (b) use more diverse frames, particularly avoiding crisis management, and speaking to economic and value-based issues; (c) use storytelling; (d) target audience groups; (e) make messaging digestible and relatable; and (f) correctly contextualize migration matters. Fifth, Welcoming America’s (2018) report “Stand Together: Messaging to Support Muslims and Refugees in Challenging Times” offer seven “principles” to bear in mind for those “developing stories and messages.” These are: (a) craft messages to confront and reshape perceptions rather than realities; (b) appeal to emotion; (c) prioritize brevity over precision; (d) ground messaging in core values; (e) use clear, concise language rather than jargon; (f) focus on actions; and (g) craft messaging around your audience not yourself. Sixth, Christiano (Reference Christiano2017, p. 12) argued that effective “public interest communications” (a) are visual or rely on metaphor; (b) connect with the values of the target audience; (c) use stories; (d) are highly focused; and (e) make use of emotion. Aside from these studies, there are numerous other reports and articles addressing relevant issues such as integration (e.g., Ahad and Banulescu-Bogdan, Reference Ahad and Banulescu-Bogdan2018) or emigration (ARK, 2018).

The recommendations of these studies, some of which overlap, are shown in Table 1. The only recommendation found in all six reports was to focus on values. However, each report offers little information on what is meant by values, which values should be focused on and how should values be used.

Moreover, the findings of these nonacademic research sometimes lack the conceptual robustness of peer-reviewed work. In the next section, I consider the academic literature on values and what consequences this has for strategic messaging on migration.

3 What are Values?

Throughout the twentieth century, psychologists made numerous attempts to classify human “values.” For each of these classifications, the constituent “values” are identifiable, are drawn from a finite set, tend to relate to each other in some systematic manner, vary little in strength or relative prioritization within individuals in the short term, vary more significantly in strength and relative prioritization between individuals and can be successfully used as predictors for attitudes on more specific, temporal issues, and human behavior.

Indeed, the importance of values as predictors of human attitudes and activity was noted at least as early as 1961 by Allport, who stated “personal values are the dominating force in life, and all of a person’s activity is directed toward the realization of his values. And so the focus for understanding is the other’s value-orientation—or, we might say, his philosophy of life (Allport, Reference Allport1961, p. 543).” Some of the more prominent human value theories include those of Murray (Reference Murray1938), Rokeach (Reference Rokeach1973), Feather and Peay (Reference Feather and Peay1975), Mahoney and Katz (Reference Mahoney and Katz1976), Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1984), Wicker et al. (Reference Wicker, Lambert, Richardson and Kahler1984), Cawley et al. (Reference Cawley, Martin and Johnson2000), Peterson and Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004), Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1992, Reference Schwartz1994, Reference Schwartz2012) and Talevich et al. (Reference Talevich, Read, Walsh, Iyer and Chopra2017). Of note, besides the sheer breadth of these human value theories, is disconcerting observation of Jost et al. (Reference Jost, Basevich, Dickson and Noorbaloochi2016, p. 351) that “these theorists” conceptions bear little resemblance to one another.

Perhaps the most eminent and broadly utilized of these values schema is Schwartz’s theory of basic personal values (1992). Schwartz defines values as cognitive representations of broad motivational goals, rather than attitudes toward particular situations, and as stable metrics of the guiding principles in individuals’ lives. This definition of values has been echoed in later works, such as Brosch and Sander (Reference Brosch and Sander2013, p. 3) who define values as “stable motivational constructs or beliefs about desirable end states that transcend specific situations and guide the selection or evaluation of behaviors and events.” Following empirical testing, Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1992) shows that there are 10 essential values and within each of these are multiple “motivational goals” with accompanying hypothesized evolutionary causal mechanisms. These values are shown to be consistent across cultures. An eleventh value—spirituality—was initially proposed but then discarded after it was shown to vary considerably by culture, in contrast to the fundamental nature of the other values. The 10 values, the basic motivation goal of each and the constituent goals—used as the foundations for the codification of the resultant values—are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Schwartz’s 10 basic personal values (1992, pp. 6–12, 24).

Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1992) shows that these values can be arranged in relation to each other on two dimensions (first, self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement and, second, conservation vs. openness to change) as shown in Figure 1. Furthermore, this arrangement shows how some values share commonalties with others, and are thus placed side-by-side, whereas others are highly dissimilar and thus placed in direct opposition to each other. The result is four higher-order value types and two resulting bipolar value dimensions. The accord between this theory and empirical testing of it is notable (e.g., Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994), partially accounting for its popularity.

Figure 1. “Revised theoretical model of relations among motivational types of values, higher order value types and bipolar value dimensions” Schwartz’s (Reference Schwartz1992, p. 45).

A handful of political scientists and psychologists have attempted to use human value-based conceptual frameworks to explain variation in political attitudes (Rokeach, Reference Rokeach1973; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994; Knutsen, Reference Knutsen1995; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003; Gunther and Kuan, Reference Gunther, Kuan, Gunther, Montero and Puhle2007; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Basevich, Dickson and Noorbaloochi2016; Dennison et al, Reference Dennison, Davidov and Seddig2020). The theorized causal mechanism underlying such an explanation relies on the assumption that “individuals hold the beliefs, opinions, and values they do because they address one or more psychological need or interest, such as those related to self-esteem maintenance, group cohesion, or rationalization of the social order (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Basevich, Dickson and Noorbaloochi2016, p. 352).” For example, conservative positions such as maintenance of hierarchy and social order have been shown to result from valuing certainty, order, safety and control (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003). In turn, variation in the value-based correlates of liberalism and conservatism have been shown to be the result of neurocognitive structure and function, “especially when it comes to the anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Basevich, Dickson and Noorbaloochi2016, p. 353; see also Amodio et al., Reference Amodio, Jost, Master and Yee2007 and Kandler et al., Reference Kandler, Bleidorn and Riemann2012).” Furthermore, Jost et al. (Reference Jost, Basevich, Dickson and Noorbaloochi2016), p. 353) argue that values mediate the relationship between personality and ideology. In short, there is a strong theoretical and empirical foundation for the supposed link between values and political attitudes.

However, according to Feldman (Reference Feldman, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003: 479), this value-based approach to explaining variation in political attitudes has “not received sufficient attention.” Schwartz et al. (Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010) also lament the absence of such investigations. They explain this dearth as the result of “the different intellectual and disciplinary origins” of political scientists and psychologists and the tendency of the former to see fundamental values in such political terms as egalitarianism, ethnocentrism, and so on, despite these plainly operating at more proximal position to more fundamental nonpolitical, all-encompassing human values (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010, p. 422). They (422) show that Schwartz’s 10 comprehensive personal values act as effective predictors of 10 core political values (e.g., law and order, civil liberties, etc.) and, ultimately, party choice at the ballot box (see also Piurko et al., Reference Piurko, Schwartz and Davidov2011; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Caprara, Vecchione, Bain, Bianchi, Caprara, Cieciuch, Kirmanoglu, Baslevent, Lönnqvist, Mamali, Manzi, Pavlopoulos, Posnova, Schoen, Silvester, Tabernero, Torres, Verkasalo, Vondráková, Welzel and Zaleski2014).

4 How Do Values Affect Attitudes to Immigration?

Despite the vast literature seeking to explain variation in attitudes to immigration, psychological explanations, including those that using personal values, remain relatively few. This dearth is only highlighted further when we consider the sizeable literature devoted to causal mechanisms such as “contact theory” or “economic marginalization,” both of which are likely to affect far fewer citizens than the universal existence of personal values and, intuitively, are likely to have weaker effects given their more superficial, short-term nature compared to deep-seated values (for overview, see Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014).

The most developed and important attempts so far to test the relationship between values and attitudes to immigration are those of Sagiv and Schwartz (Reference Sagiv and Schwartz1995), Davidov and Meuleman (Reference Davidov and Meuleman2012), and Davidov et al. (Reference Davidov, Meuleman, Billiet and Schmidt2008, Reference Davidov, Meuleman, Schwartz and Schmidt2014). In these studies, the authors use pan-European data to show that Schwartz’s value system can successfully predict attitudes to immigration. The authors find that the two values of “universalism” and “benevolence” increase positivity to immigration, particularly the former, whereas the three values of “security,” “conformity” and “tradition”—together making up the “conservation” higher order value—decrease positivity to immigration.

5 Demonstrating the Relationship Between Values and Attitudes to Immigration

I now briefly turn to demonstrating this relationship between values and attitudes to immigration by comparing the entire value-orientation of different groups of Europeans according to their attitudes to migration, rather than testing specific relationships. To do so, I use data from the ninth, most recent, wave of the European Social Survey (ESS). This is formed of data collected between 2018 and 2019 in 19 countries.Footnote 1 The ESS is a biannual cross-national survey based on face-to-face interviews in each participating country. The ESS is unique in that it provides high-quality data, covering an extremely broad range of political attitudes, among other variables, across every region of Europe, as well as Israel. Respondents are selected by probability sampling of residents who are aged 15 or over. The ESS allows for weighting by both country population size and according to stratification.

The ninth round of the ESS includes three questions measuring attitudes to the admission of immigrants.Footnote 2 These are:

• “Should your country allow (a) many, (b) some, (c) a few, or (d) no immigrants from poorer countries out of Europe?”

• “Should your country allow (a) many, (b) some, (c) a few, or (d) no immigrants of a different race/ethnic group from the majority?”

• “Should your country allow (a) many, (b) some, (c) a few, or (d) no immigrants of the same race/ethnic group from the majority?”

I use attitudes to immigration instead of attitudes to refugees, which are less commonly asked with, typically, more positive responses. Using these three variables, I create a variable that is the mean response to the above three questions, which, therefore, exists on the same 1–4 scale, with 1 indicating that the respondent was in favor of the admission of “many” of each of the three groups and 4 indicating that the respondent was in favor of the admission of “none” of the each of the three groups. For the purposes of visualization, I then place each respondent into one of four groups: strongly anti-immigration (scoring 3 or above; weighted 26.3% of Europeans); leaning anti-immigration (scoring between 2 and 3; weighted 20.0% of Europeans); leaning pro-immigration (scoring exactly 2; 30.5% of Europeans); and strongly pro-immigration (scoring less than 2; 23.2% of Europeans).

The ESS includes 21 variables that seek to measure Schwartz’s 10 basic human values, as described above. These are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Ten values and their ESS 2014 operationalization Schwartz’s (Reference Schwartz1992).

In Figure 2, the distribution of values across each of the four groups is outlined, measured as z-scores (i.e., standard deviations from the mean, which is 0). A higher score indicates that the value is more common in that group than in the general population, with a negative scoring indicating the opposite. As we can see, there is a clear pattern whereby:

• Strongly anti-immigration Europeans tend to value conformity, security, tradition and power above the European average. Conversely, they are far less likely to value universalism, benevolence, self-direction, stimulation or hedonism.

• Europeans strongly pro-immigration tend to have the opposite value orientation, but far more magnified. They have the most skewed value orientation of any group and, above all, value universalism highly and undervalue security and conformity.

• The two more moderate groups have, by contrast, balanced value orientations.

Figure 2. Value orientations of four groups of Europeans.

6 How to Communicate on Migration Using Values

Having defined values and demonstrated their relationship with attitudes to immigration, we now turn to considering how to use this information to persuasively communicate on migration using values. Overall, based on the above literature, we can deduce that messaging is most likely to elicit sympathy when the values it contains are concordant with those of recipient, this relationship is shown in Figure 3. In other words:

Recipients will be sympathetic to a message when its values align with their own and they will be antipathetic to a message when its values diverge from their own.

Figure 3. A model of the effect of value-based messaging on the effectiveness of the message.

Specifically to the case of migration, and following on from the review on the relationship between values and attitudes to immigration, when migration messaging is framed in values of self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence) or openness to change (self-direction, stimulation, hedonism) it is more likely to be supported by those already favoring immigration. When migration messaging is framed in values of conservation (security, tradition, or conformity) or self-enhancement (power and to a lesser extent achievement) it is more likely to be supported by those already opposing immigration. To be most effective, messaging should use the opposite values of those already associated with its argument. For pro-immigration messaging, this means, conformity, tradition, security and power. For anti-immigration messaging this means universalism, benevolence, and self-direction. These relationships are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. The effect of the values-basis of pro- and anti-immigration messaging on attitudes to immigration.

7 Examples of Existing Value-Based Communication on Migration

We now move to applying the above theoretical expectations to classifying real-world examples of migration communication. I use an inventory of 135 migration campaigns as collected by the ICMPD as the source of the campaigns. Because this inventory was not collected for this article, it can be considered as having the advantages of incidental data.

The contents of the inventory are attached to the appendix of this article. The campaigns include those from the period 2009–2019 in EU member states and states in the southern and eastern Mediterranean (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia). Campaigns come from national governments, international organizations, NGOs and the private sector and some political parties that held campaigns specific to migration policy. Campaigns are defined to not include media coverage but instead be planned activities with a goal of social or political change.

The vast majority of the campaigns within the inventory have the aim of changing attitudes toward immigration, often among other aims. However, a number are specifically related to emigration, smuggling and trafficking prevention or advertising services. I remove these campaigns for the sake of this analysis, leaving 106 campaigns. I then divide these into two groups, those with a pro-immigration message (98 campaigns) and those with an anti-immigration message (eight campaigns). Clearly, the inventory is by no means balanced, owing in large part to the sources of the campaigns (see above). It is neither by any means exhaustive, given that anti-immigration policy campaigns in the last 10 years by radical right parties across Europe would likely number in the hundreds; though it does provide indicative and illustrative examples, as we shall see. I consider

7.1 The ubiquity of “migrant’s journey” videos

Of these 98 campaigns, 35 held focussed on the “migrant’s journey” narrative, essentially a retrospective narrative that typically details the trials and tribulations migrants faced leading to their decision to emigration, while on the journey and again once resident in the host country. These almost always held the overarching narrative point that migrants were victims, with the focus on refugees. Notably, 27 of these 35 campaigns were made in video format. They are summarized in Appendix 1. In Figure 4, I show four stills from a fairly typical graphical video of the journey undertaken by a refugee from the moment of fleeing her country to receiving refugee status in Estonia. A billboards campaign was launched in five Estonian cities to introduce the webpage. The third part of the campaign was a direct mailing to reach target groups in cities and rural areas. The delivered postcards told the stories of three different refugees who were forced to flee their countries.

Figure 4. Example of a “migrant’s journey” prototype of migrant communication. Source: Estonian Human Rights Center. Available at https://humanrights.ee/pagulane/eng/.

These campaigns, arguably, focus on the value of benevolence, as well as universalism. These campaigns are therefore likely to be most effective at mobilizing those who are already sympathetic to the message—for example, by encouraging fundraising or political mobilization. However, these campaigns as attempts to move public opinion are somewhat limited, regardless of their values-basis, because they are retrospective and therefore unable to fulfil the strategic forward-looking motivational goals that values underpin. Moreover, they are unlikely to be effective at convincing moderate citizens given their focus on a single value that is typically already associated with refugees.

8 Remaining Pro-Migration Campaigns

The remaining 63 campaigns represent a very broad spectrum in terms of format and approach. Of these 63 campaigns, 18 focus on migrants’ lives once living in the host country (some others partially have this focus). The majority of these, around 16 of the 18 here, have no obvious, particular value-basis, instead focusing purely on attempting to humanize migrants. The value-basis of these could be classified as universalism. Four examples of these are shown in Figure 5 (the full list is shown in Appendices 2 and 3).

Figure 5. Four examples of “humanising migrants” campaigns. Clockwise, from the top: AMITIE campaign; Living Together campaign (#شارك_الصداقة, “#sharethefriendship); Vota per me (Vote for me) campaign; Gegen Vorurteile (Against prejudice) campaign.

However, two of these had more explicit values-bases beyond universalism and benevolence. These clearly pointed to the ability of migrants to support other broad motivation goals. Three social media posts from one of these campaigns—"We are Upper Austria” (Wir Sind Oberösterreich)—and one from a series entitled “I am a stranger until you get to know me” (sunt un străin, până mă cunoști) are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Values-based pro-migration messaging. “We are Upper Austria”; “Yesterday refugee, today medic. I am a stranger until you get to know me.”

These examples express migration in value-terms. Most obviously this is in terms of the economic or labor contribution of each of the migrants pictured. In Schwarz’s values-scheme, this would fall under the value category of “power.” However, more subtly, each of the pieces of communication speak to other values that fall under the “conservation” higher order value type. The three Austrian examples each show migrants collaborating with native Austrians, in two cases wearing uniforms: this is an allusion to “conformity.” The examples of the firefighter, medic and nurse, each concerned with health and safety, point to the value of “security.” Finally, the implied apprenticeship (or similar) relationships in the top two examples may also allude to the value of “tradition.” Overall, each of these messaging examples has a value-basis that includes at least one of the values regularly associated with anti-immigration sentiment. According to this article’s theoretical model, we should therefore expect these to be more effective examples of persuasive messaging. The remaining 45 pro-immigration campaigns came in a remarkable variety of formats. However, few contained an obvious values-basis. This is not to suggest that they were ineffective. Many indeed fulfilled other recommendations as laid out earlier in this article.

9 Values-Based Anti-Immigration Messaging

The inventory of migration messaging campaigns that this study is based on included just eight anti-immigration campaigns (outlined in Appendix 4). However, all of them had a value-basis. Furthermore, the majority spoke to values associated with pro-immigration sentiment and so potentially appealing to moderates. In Figure 7, I outline examples of those based on the values of “security,” “tradition,” “conformity,” and “power.”

Figure 7. Values-based (“security,” “tradition,” “conformity,” and “power”) anti-immigration messaging. Top left: “The forcible relocation endangers our culture and traditions.” Top right: “Migration pact = focus on maintaining the culture of origin of migrant.” Bottom left: “So that Europe does not become Eurabia!” Bottom right: “Migration pact = difficulty in organizing returns.”

The top left is a page from an anti-migrant booklet passed out by the Hungarian government. The title reads “The forcible relocation endangers our culture and traditions” and then says “Several hundred ‘no-go’ areas in Europe’s big cities” itself pointing to the value of security. The top right example is from the Flemish far-right party “Flemish Block.” It reads “Migration pact = focus on maintaining the culture of origin of migrant.” The bottom right is also from the same series and reads “Migration pact = difficulty in organizing returns.” These respectively are based on the values of “conformity” and “tradition” and “security” and “power.” Finally, the bottom left campaign comes from the German far right party “Alternative for Germany” and reads “So that Europe does not become Eurabia!” while showing an Orientalist painting of a white woman at an Arab slave auction, speaking to the values of “security” and “power.”

In Figure 8, we see four examples of anti-immigration messaging based on the values of “universalism,” “benevolence,” “self-direction,” and “stimulation.” The top left comes from a campaign against the Global Compact for Migration and implies that the “migration pact” and, presumably, migration moreover are threats to tolerance rather than a form of tolerance, a “universalist” value. In doing so, it speaks to an argument often used by the radical right in Europe regarding the social conservatism, particularly on issues of LGBT and women’s rights, of some migrants. The second, from the youth organization of the French far right party “Front National” states that “Sandra has been sleeping in her car with her son for three months. Unfortunately for her, she is not a migrant,” making an argument based on the value of “benevolence.” The bottom two, both from the Identitarian Generation anti-immigration social movement state, on the left, “I live an experience out of the ordinary. I defend my country” and, on the right, “I want to be the new breath that is going to change our country.” These speak to “stimulation” and “self-direction,” respectively.

Figure 8. Values-based (“universalism,” “benevolence,” “self-direction,” and “stimulation”) anti-immigration messaging. Top right: “Sandra has been sleeping in her car with her son for three months. Unfortunately for her he is not a migrant”; Bottom left: “I live an experience out of the ordinary. I defend my country.” Bottom right: “I want to be the new breath that is going to change our country.”

10 Discussion

This article started by providing a summary of key recommendations from existing best-practice guides for migration communication. Though the most common recommendation is to focus on values-based messaging, very little work has considered what values-based messaging is and what type of value-based messaging is likely to work regarding migration. I then summarized the academic literature on values, focussing on Schwarz’s theory of basic human values: broad, stable motivational goals that individuals hold in life, which predict attitudes to specific issues and behavior. The relationship between these 10 values are graphically displayed: universalism, benevolence, stimulation, and self-direction are associated with pro-immigration attitudes, whereas conformity, security, tradition, and power are associated with anti-immigration attitudes.

Theoretically, I argue that aligning migration policy communication with the values of the target audience values is likely to elicit greater sympathy for the message. Values-based messages that do not align with those of the audience are less likely to elicit sympathy and may elicit antipathy. This article then analyzed migration policy communication examples from an inventory of 135 campaigns from both sides of the Mediterranean provided by the ICMPD. It is then systematically considered how well these campaigns align with expectations as derived from the theoretical framework. Few pro-migration campaigns contained value-based messaging, whereas all anti-migration campaigns did. Similarly, very few pro-migration campaigns included values besides “universalism” and “benevolence,” whereas anti-migration campaigns included values associated with both pro- and anti-migration attitudes. Examples of each case were visually demonstrated.

This article provides policymakers with an understanding of what values-based policy communication is and how, using robust data, they can communicate policies that are concordant with the values of their audiences in a way likely to elicit sympathy. Already campaigns related to migration and integration have done this: for example, the campaign by British Future showing Britons of Asian descent, particularly Muslims, engaging in the tradition of wearing poppies in remembrance of war dead, many of whom were from the Indian sub-continent; also appealing to conformity in terms of a common collective military background (Townsend, Reference Townsend2019). Although this article uses the example of migration policy communication, the same approach can be taken for policies on any politically controversial issue. Future migration policy communication that seeks to incorporate values should use a systematic approach such as that found in this study and seek to incorporate the values of the target audience. Future research should robustly test the effects of each of these kinds of communication using experimental methods, be they field, lab or survey experiments. Alternative values-scheme and forms psychological predispositions, for example, personality types, should also be considered. Furthermore, academic studies of psychological schema, such as Schwarz’s, could be combined with the work of discourse analysts such as Wodak (Reference Wodak2011), Wodak, Reference Wodak2015; Wodak and Forchtner, Reference Wodak and Forchtner2017) whose linguistic approach to the study of politics, including the far right, is relevant. Finally, the normative and ethical implications of persuasive messaging campaigns, using values or otherwise, are naturally controversial—particularly on the issue of immigration. Similarly, experiments based on such theoretical arguments as advanced in this article may also raise ethical concerns, particularly those done on a large scale (see Shaw, Reference Shaw2016, regarding Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Guillory and Hancock2014).

Funding Statement

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous support of the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet; grant no. 2019/00504). This work was supported by the EUROMED Migration IV Programme, funded by the European Union (EU) and implemented by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability Statement

Data in this article comes, first, from the open-access European Social Survey, and a number of migration communication case studies, available as appendices in the supplementary materials section.

Authorship Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.; Data curation, J.D.; Formal analysis, J.D.; Funding acquisition, J.D.; Investigation, J.D.; Methodology, J.D.; Project administration, J.D.; Resources, J.D.; Software, J.D.; Supervision, J.D.; Validation, J.D.; Visualization, J.D.; Writing-original draft, J.D.; Writing-review & editing, J.D.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/dap.2020.17.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.