Policy Significance Statement

For policy-makers, a data protection-focused data commons encourages data subject participation in the data protection process. Empowering data subjects can increase data’s value when used in open and transparent ways. As our research applies participatory methodologies to collaborative data protection solutions, policy-makers can go beyond legal considerations to promote democratic decision-making within data governance. To co-create data protection solutions, we provide a checklist for policy-makers to implement a commons from the planning and public consultation process to incorporating the commons in practice. Policies for creating a commons can ease the burden of data protection authorities through preventative measures. Importantly, establishing a data protection-focused data commons encourages policy-makers to reconsider balances of power between data subjects, data controllers, and data protection stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Rapid technological innovation has changed how we, as individuals, interact with companies that use our personal data in our data-driven society. Data breaches and privacy scandals have frequently come to light, such as the widespread development of contact-tracing applications for invasive pandemic surveillance (Cellan-Jones, Reference Cellan-Jones2020), the Cambridge Analytica scandal where 50 million Facebook profiles were used to build models with the aim of influencing elections (Cadwalladr and Graham-Harrison, Reference Cadwalladr and Graham-Harrison2018), and the datafication of our everyday lives through the Internet of Things (Hill and Mattu, Reference Hill and Mattu2018). As a result, individuals are more cautious about data protection, privacy, and what information they put online (Fiesler and Hallinan, Reference Fiesler and Hallinan2018; Cisco Secure 2020 Consumer Privacy Survey, 2020; Perrin, Reference Perrin2020; Cuthbertson, Reference Cuthbertson2021; Lafontaine et al., Reference Lafontaine, Sabir and Das2021; Laziuk, Reference Laziuk2021).

Both laws and technological solutions aim to address concerns about data breaches and privacy scandals that affect the personal data of individuals as data subjects. Data protection laws, such as the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR; European Union, 2016) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (California State Legislature, 2018), focus on putting responsibilities on data controllers and enforcement. As the authors are based in the United Kingdom, we focus our work on the GDPR. This regulation introduces significant changes by acknowledging the rise in international processing of big datasets and increased surveillance both by states and private companies. The GDPR clarifies the means for processing data, whereby if personal data are processed for scientific research purposes, there are safeguards and derogations relating to processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes, or statistical purposes (Article 89), applying the principle of purpose limitation (Article 5). Data subject rights also aim to provide data subjects with the ability to better understand or prevent their data to be used, including the right of access (Article 15), the right to erasure (Article 17), and the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing (Article 22). New technologies have also attempted to give users the ability to control and recognize their sovereignty over their own data. Some tools such as Databox (Crabtree et al., Reference Crabtree, Lodge, Colley, Greenhalgh, Mortier and Haddadi2016; a personal data management platform that collates, curates, and mediates access to an individual’s personal data by verified and audited third-party applications and services) and, most prominently, Solid (Mansour et al., Reference Mansour, Sambra, Hawke, Zereba, Capadisli, Ghanem, Aboulnaga and Berners-Lee2016; a decentralized peer-to-peer network of personal online data stores that allow users to have access control and storage location of their own data) prioritize creating new data infrastructures that supply online data storage entities which can be controlled by users and encourages the prevention of data-related harms as opposed to remedying harms after the fact. Other applications attempt to facilitate data reuse with privacy-by-design built in, such as The Data Transfer Project (2018; an open-source, service-to-service platform that facilitates direct portability of user data), OpenGDPR (2018; an open-source common framework that has a machine-readable specification, allowing data management in a uniform, scalable, and secure manner), and Jumbo Privacy (2019; an application that allows data subjects to backup and remove their data from platforms, and access that data locally). Such technologies help data subjects better understand the rights they may have under current regulations, as well as provide an avenue in which those rights can be acted upon.

While data protection laws and technologies attempt to address some of the potential harms caused by data breaches, they inadequately protect personal data. Current approaches to data protection rely on a high level of understanding of both the law and the resources available for individual redress. Regarding legal solutions, focusing on individual protection assumes that data subjects have working knowledge of relevant data protection laws (Mahieu et al., Reference Mahieu, Asghari and van Eeten2017), access to technology, and that alternatives exist to the companies they wish to break away from (Ausloos and Dewitte, Reference Ausloos and Dewitte2018). Although people are more aware of their data subject rights, these are not well understood (Norris et al., Reference Norris, de Hert, L’Hoiry and Galetta2017). Only 15% of European Union (EU) citizens indicate that they feel completely in control of their personal data (Custers et al., Reference Custers, Sears, Dechesne, Georgieva, Tani and van der Hof2019). Evaluating location-based services, Herrmann et al. (Reference Herrmann, Hildebrandt, Tielemans and Diaz2016) find that individuals do not necessarily know all the inferences that are made using their data and thus do not know how they are used. Importantly, individuals are unaware of, and unable to correct, false inferences, making the collection, transfer, and processing of their location data entirely opaque. Additionally, laws focusing on placing data protection responsibilities on data controllers and empowering enforcement bodies assume that data controllers understand how to implement those responsibilities and that enforcement is successful (Norris et al., Reference Norris, de Hert, L’Hoiry and Galetta2017).

While technological tools can be useful if they offer controls that limit the processing of personal data according to data subject preferences, they result in the responsibilization of data protection (Mahieu et al., Reference Mahieu, Asghari and van Eeten2017), where individuals have the burden of protecting their own personal data as opposed to data controllers themselves. In the case of data infrastructures, these tools may not be able to solve challenges related to the ownership of data, and it is unclear how they would meet GDPR requirements (Bolychevsky, Reference Bolychevsky2021). Existing tools also frame privacy as control by placing individual onus on data protection, without supporting other GDPR principles such as data protection by design or data minimization. Tools may further assume that data subjects already have a sufficient level of understanding of the data subject rights they have by focusing on more fine-tuning privacy settings and features. They also require data subjects to trust the companies and the technological services they provide. Finally, these solutions do not offer means for collaborative data protection where information gathered from individuals could be shared among each other. This could disenfranchise data subjects from each other and prevent them from co-creating data protection solutions together through their shared experiences.

Given the limited ability for data subjects to voice their concerns and participate in the data protection process, we posit that protecting data breaches and data misuse resulting from mass data collection, processing, and sharing can be improved by actively involving data subjects in co-creation through a commons. Using commons principles and theories (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990) and applying engagement mechanisms to innovations in our digital economy (Fung, Reference Fung2015), we suggest that a commons for data protection, a “data commons,” can be created to allow data subjects to collectively curate, inform, and protect each other through data sharing and the collective exercise of data protection rights. By acknowledging the limitations of data protection law and legal enforcement coupled with the desire for data-driven companies to collect and process and increasing amount of personal data, a data protection-focused data commons can help mitigate the appropriation of personal data ex post and ex ante, where data subjects are engaged throughout the process and can make the most of existing data protection regulations to co-create their own data protection solutions. In this paper, we examine how a data commons for data protection can improve data subject participation in the data protection process through collaboration and co-creation based on experiences from commons experts.

This paper is outlined as follows. First, we explore existing data stewardship frameworks and commons to better understand how they manage and govern data, identifying current solutions and why a data protection-focused data commons can support the protection data subjects’ personal data through user engagement (Section 2). We then illustrate our interview methodology in identifying the challenges of building a commons and the important considerations for a commons’ success (Section 3). In Section 4, we share our findings from commons experts and detail the key themes as they relate to building a commons for data protection. Based on our analysis, we then apply our findings to the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework and map the framework into an actionable checklist of considerations and recommendations for policy-makers to implement a collaborative data protection-focused data commons in practice (Section 5) as well as the next stages for deploying a commons (Section 6). Finally, we conclude that a co-created data protection-focused data commons can support more accountable data protection practices, management, and sharing for the benefit of data subjects, data controllers, and policy-makers to overcome the limitations of laws and technologies in protecting personal data.

2. Background

This section is split into four parts: First, we describe existing collaborative data stewardship frameworks by empirically assessing their attempt to support better data protection for data subjects through direct engagement. Then, we outline the commons and existing commons applications. Next, we identify commons, urban commons, and data commons applications that are relevant to data protection. Finally, we identify theoretical applications of data protection in a data commons and illustrate our research questions to support the development of a practical framework for including data subjects in the data protection process through a data commons.

2.1. Data stewardship frameworks

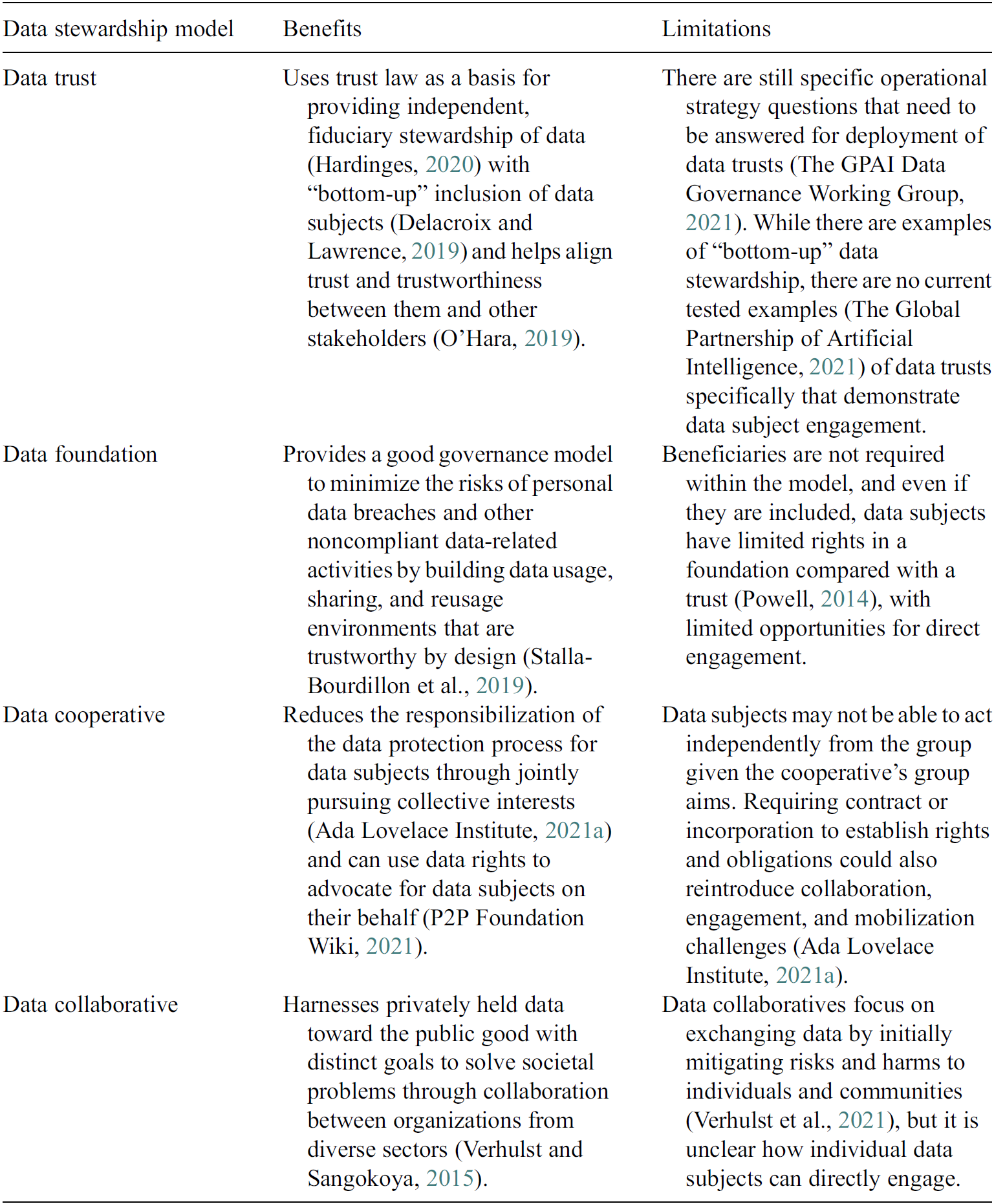

Data stewardship refers to the process by which “individuals or teams within data-holding organizations … are empowered to proactively initiative, facilitate, and coordinate data collaboratives toward the public interest” (Governance Lab, 2021b). Data stewards may facilitate collaboration to unlock the value of data, protect actors from harms caused by data sharing, and monitor users to ensure that their data use is appropriate and can generate data insights. New data stewardship frameworks, such as data trusts, data foundations, and data cooperatives, have been devised in order to protect data subjects as well as to involve them and other stakeholders in the co-creation of data protection solutions (Data Economy Lab, 2021b; Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021c). While these data stewardship frameworks may help mobilize data protection rights, there are significant organizational, legal, and technical differences between them. Furthermore, they also face definitional, design, and data rights-based challenges. The benefits and challenges faced by these frameworks are discussed in the following paragraphs and summarized in Table 1. A data trust is a legal structure that facilitates the storage and sharing of data through a repeatable framework of terms and mechanisms, so that independent, fiduciary stewardship of data is provided (Hardinges, Reference Hardinges2020). Data trusts aim to increase an individual’s ability to exercise their data protection rights, to empower individuals and groups in the digital environment, to proactively define terms of data use, and to support data use in ways that reflect shifting understandings of social value and changing technological capabilities (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b). Although data trusts refer to trusts in the legal sense, they also imply a level of trustworthy behavior between data subjects and other data trust stakeholders (O’Hara, Reference O’Hara2019). While data trusts are promising in their ability to use trust law in order to protect data rights, it is currently unclear what powers a trustee tasked with stewarding those rights may have, and the advantages the data subjects as the trust’s beneficiaries may gain (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b). Data trusts could in theory support responses to certain data subject rights requests, particularly through access requests, but it may be difficult to benefit from other rights such as portability and erasure to support data subjects through trusts. In the latter case, there may be tensions regarding trade secrets and intellectual property (Delacroix and Lawrence, Reference Delacroix and Lawrence2019; Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b). Moreover, the agency that data subjects may exercise within the data trust mechanism remains an open question. Efforts have encouraged the creation of “bottom-up” data trusts that aim to empower data subjects to control their data. While data subject vulnerability and their limited ability to engage with the day-to-day choices underlying data governance is acknowledged by these (Delacroix and Lawrence, Reference Delacroix and Lawrence2019), many data trusts remain top-down in nature and overlook the data subject’s perspective.

Table 1. Data trust, data foundation, data cooperative, and data collaborative stewardship models summarized by their benefits and limitations in considering data subject engagement

It is still unclear how existing fiduciary structures can fully realize their fiduciary responsibilities toward data subjects within digital spaces (McDonald, Reference McDonald2021; The Global Partnership of Artificial Intelligence, 2021; Data Economy Lab, 2021c). Previous pilots have attempted to clarify how data trusts can be put into practice (although without the application of trust law) by supporting the initiation and use of data trusts with a data trust life cycle (Open Data Institute, 2019). Recent projects such as the Data Trusts Initiative can help clarify how the bottom-up data trusts model can operate in practice in realizing fiduciary responsibilities (Data Trusts Initiative, 2021). Other frameworks—data foundations, data cooperatives, and data collaboratives—have also included citizen representation and engagement as an integral part of their design (Involve, 2019). There are, however, still many practical challenges in this respect (The GPAI Data Governance Working Group, 2021), particularly with questions relating to scaling and sustaining data sharing (Lewis, Reference Lewis2020). To address some of these challenges, data foundations have been developed as a good governance model for “responsible and sustainable nonpersonal and personal data usage, sharing, and reusage by means of independent data stewardship” (Stalla-Bourdillon et al., Reference Stalla-Bourdillon, Carmichael and Wintour2021). Data foundations rely on foundation law and view data subjects as potential beneficiaries within the model (Stalla-Bourdillon et al., Reference Stalla-Bourdillon, Wintour and Carmichael2019). However, beneficiaries are not required within the model and even if they are included, data subjects have limited rights in a foundation compared with a trust (Powell, Reference Powell2014).

A data cooperative is a group that perceives itself as having collective interests, which would be better to pursue jointly than individually (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021a). Cooperatives are “autonomous associations of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” (International Cooperative Alliance, 2018). Data cooperatives can harness the value of data in common, where the growing real time ubiquity of digital information could help its members plan more justly and efficiently than the price mechanism in our data-driven economy (New Economics Foundation, 2018). For example, the U.S.-based Driver’s Seat Cooperative is a driver-owned data cooperative that helps gig-economy workers gain access to work-related smartphone data and get insight from it with the aim to level the playing field in the gig economy (Driver’s Seat, 2020).

Data cooperatives can liberate personal data through data subject access requests and can advocate for data subjects on their behalf (P2P Foundation Wiki, 2021). However, cooperatives often rely on contract or incorporation to establish rights, obligations, and governance, which could reintroduce some challenges related to collaboration and mobilization the framework was intended to limit (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021a), where there may also be tension between reconciling individual and collective interests (Data Economy Lab, 2021a). Navigating conflict in cooperatives may be carried out through voting or other governance structures, where data cooperatives may function as fiduciaries as well (Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, Stanford University, 2021). Similarly, data collaboratives (Governance Lab, 2021a) can harnesses privately held data toward the public good through collaboration between different sectors. Data collaboratives differ from other frameworks, such as data trusts, because the former have the distinct goal to solve societal problems through collaboration between organizations from diverse sectors (Verhulst and Sangokoya, Reference Verhulst and Sangokoya2015). They can support the rethinking of rights and obligations in data stewardship (Verhulst, Reference Verhulst2021) to mitigate inequalities and data asymmetries (Young and Verhulst, Reference Young, Verhulst, Harris, Bitonti, Fleisher and Skorkjær Binderkrantz2020).

Despite many efforts to help define and clarify the legal, organizational, and technical dimensions of data trusts and other data stewardship frameworks, one of the challenges is that no broadly accepted definition of data stewardship has emerged (Stalla-Bourdillon et al., Reference Stalla-Bourdillon, Thuermer, Walker, Carmichael and Simperl2020). Their broad applications and widespread theoretical adoption have resulted in varied definitions and so require further disambiguation from each other in order to implement (Susha et al., Reference Susha, Janssen and Verhulst2017). Even if these frameworks are clearly defined, data trusts and data collaboratives rely on separate legal structures to facilitate the protection of personal data through the creation of a new data institution through legal means (Open Data Institute, 2021). It is acknowledged that each of these frameworks has the legal safeguarding of data subjects at their core. Nonetheless, the requirement of additional legal structures could further complicate the data protection process for both the organizations willing to adopt these frameworks as well as data subjects’ ability to engage with them. Data stewardship frameworks also face several design challenges associated with the inclusion of data protection principles and data subject engagement within the framework itself. Although data protection by design may be considered (Stalla-Bourdillon et al., Reference Stalla-Bourdillon, Thuermer, Walker, Carmichael and Simperl2020), the frameworks may still focus more on how the data generated can be used for specific purposes as opposed to supporting data subjects’ rights and agency over their personal data. While bottom-up approaches which focus on data subject agency are increasingly being considered as integral to the creation of existing data stewardship frameworks, they are not mandatory and may differ in their application. Although data subjects can be both settlors and beneficiaries within data trusts and beneficiary members in data cooperatives, individuals and groups of data subjects may still be excluded from participation in two circumstances: first, where they have not been consulted in the design of the framework, and second, where there is a lack of clarity on what a bottom-up approach entails (The Global Partnership of Artificial Intelligence, 2021). It is currently unclear how genuine and appropriate engagement mechanisms can be deployed (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b). Moreover, it is unclear whether or how existing data stewardship mechanisms apply participatory and action research-based solutions (Bergold and Thomas, Reference Bergold and Thomas2012), to ensure that data subjects’ preferences and perspectives are substantively taken into account as part of ongoing governance (Rabley and Keefe, Reference Rabley and Keefe2021).

Finally, data-related rights may not be fully realized within current data stewardship frameworks. Although data stewardship frameworks benefit from not requiring extra legislative intervention that can take time to produce and is difficult to change (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b), the frameworks also do not always interface with existing public regulatory bodies and their mechanisms, which enforce data-related rights, as part of their solution. It is also unclear how current data stewardship frameworks would support data subject recourse should there be personal data breaches. Data cooperatives often do not preserve privacy as a first priority (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021a). While data trusts may introduce trustees and experts that are able to prevent potential data-related harms (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021b), it is not mandatory for them to do so. Given that seeking remedies from data protection harms is not mandatory within existing data stewardship models, data subjects may be left with limited support on how to exercise data subject rights under data protection regulations.

2.2. The commons

The commons, as developed by E. Ostrom, considers individual and group collective action, trust, and cooperation (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). The commons guards a common-pool resource (CPR), a resource system that is sufficiently large as to make it costly to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use and may be overexploited. Respecting the competitive relationships that may exist when managing a CPR, the commons depends on human activities, and CPR management follows the norms and rules of the community autonomously (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990). The CPR enables “transparency, accountability, citizen participation, and management effectiveness” where “each stakeholder has an equal interest” (Hess, Reference Hess2006). Central to governing the commons is recognizing polycentricity, a complex form of governance with multiple centers of decision-making, each of which operates with some degree of autonomy (V. Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961). Its success relies on stakeholders entering contractual and cooperative undertakings or having recourse to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010). The norms created by the commons are bottom-up, focusing on the needs and wants of the community and collectively discussing the best way to address any issues (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2012). This is illustrated by E. Ostrom’s case studies of Nepalese irrigation systems, Indonesian fisheries, and Japanese mountains.

From these case studies, E. Ostrom identifies eight design principles that mark a common’s success with a robust, long-enduring, CPR institution (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990):

-

1. Clearly defined boundaries: Individuals or households who have rights to withdraw resource units from the CPR must be clearly defined, as must the boundaries of the CPR itself;

-

2. Congruence between appropriation and provision rules and local conditions: Appropriation rules restricting time, place, technology, and/or quantity of resource units are related to local cognitions and to provision rules requiring labor, material, and/or money;

-

3. Collective-choice arrangement: Most individuals affected by the operational rules can participate in modifying the operational rules;

-

4. Monitoring: Monitors, who actively audit CPR conditions and appropriate behavior, are accountable to the appropriators or are the appropriators;

-

5. Graduated sanctions: Appropriators who violate operational rules are likely to be given assessed graduated sanctions (depending on the seriousness and context of the offence), from other appropriators, by officials accountable to these appropriators, or by both;

-

6. Conflict-resolution mechanisms: Appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among appropriators or between appropriators and officials;

-

7. Minimal recognition of rights to organize: The rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities; and

-

8. For larger systems, nested enterprises for CPRs: Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises.

As the commons on its own focuses on creating a framework to be adapted to different cases and environments, we next consider how these principles may be applied to a digital setting and data protection more specifically.

2.3. Encouraging collaboration and data subject engagement in a commons

The commons can act as a consensus conference (Andersen and Jæger, Reference Andersen and Jæger1999) to encourage dialogue among data subjects, experts, and policy-makers, experts and ordinary citizens, creating new knowledge together for the common good. While existing data stewardship frameworks may take their members’ vested interests into consideration, the commons has a number of advantages for data subject engagement. First, a commons, through its stakeholder considerations and bottom-up norms, can directly engage data subjects in the creation and iterative improvement of the framework. Data subjects are then able to actively and continuously reflect on their individual and community preferences when it comes to managing a CPR. Second, it can advance the protection of personal data as part of democratic and participatory governance (Fung, Reference Fung2015). Privacy and data protection may be addressed directly not only as legal rights, but also as part of the political, social, and cultural landscape (Dourish and Anderson, Reference Dourish and Anderson2006). Third, the commons can offer an alternative form of data stewardship in that it applies polycentric design principles (Dourish and Anderson, Reference Dourish and Anderson2006) and because of the commitment to these principles adopts public engagement methodologies to engage with and empower data subjects. These methodologies, which have their roots in Human–Computer Interaction and Science and Technology Studies, can increase public engagement not only with science, but also with legal, policy, and technical innovations (Wilsdon and Willis, Reference Wilsdon and Willis2004; Wilsdon et al., Reference Wilsdon, Wynne and Stilgoe2005; Stilgoe et al., Reference Stilgoe, Lock and Wilsdon2014). Public engagement beyond the development of science, law, and policy is also necessary for establishing trust (Wynne, Reference Wynne2006), where the commons can support direct engagement between data subjects as well as to other stakeholders through its infrastructure as well as the application of conflict-resolution mechanisms based on E. Ostrom’s design principles. Finally, the focus of these methods on worst-case scenarios—such as data breaches or privacy violations—is particularly helpful (Tironi, Reference Tironi2015). When addressing the likelihood of these risks occurring, the collective identification of shared goals and purpose can be enabled. Data subject agency, engagement, and empowerment may thus be garnered through the democratic expression of individual preferences toward improving individual and collective commitment toward a shared goal, while carefully juggling the interdependence between civil society and legal–political mechanisms (De Marchi, Reference De Marchi2003).

2.4. Adapting the commons for transparency and accountability

Using E. Ostrom’s design principles and polycentricity as a form of governance, the commons framework has been adapted for information, data, and urban environments. These principles and frameworks can be adapted for data protection to address data-related harms by recognizing the limitations of both law and technologies, encouraging collaborative solutions for protecting personal data, and allowing data subjects to regain autonomy of their data protection process.

2.4.1. Knowledge and information commons

To address the rise of distributed, digital information, Hess and Ostrom (Reference Hess and Ostrom2007) developed the information or knowledge commons, where knowledge is the CPR. As new technologies enable the capture of information, the knowledge commons recognizes that information is no longer a free and open public good and now needs to be managed, monitored, and protected for archival sustainability and accessibility. Crucially, the commons addresses data-related governance challenges that arise due to spillovers created by the reuse of data, so increasing its value over time (Coyle, Reference Coyle2020). This is further exemplified when data are linked together, creating new uses and value for the same data. Socioeconomic models have also been suggested for commons-based peer production, where digital resources are created, shared, and reused in decentralized and nonhierarchical ways (Benkler et al., Reference Benkler, Shaw, Hill, Malone and Bernstein2015). Without a commons, the newly generated knowledge may not be available to the original creators of the data in the first place. As a result, the knowledge commons can support data subjects in accessing the personal and social value of their data while ensuring its quality and storing it securely. More generally, commons theory has also been used to support democratic practice in digitally based societal collaborations in order to ensure diversity, define the community and the community’s obligations, and build solidarity (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Levi, Brown, Bernholz, Landemore and Reich2021).

In assessing the feasibility of a knowledge commons, E. Ostrom’s IAD framework can be used to study an institution’s community, resource dynamics, and stakeholder interests. The IAD supports the creation of a commons and analyzes the dynamic situations where individuals develop new norms, rules, and physical technologies. Adopting the IAD framework’s core sections on biophysical characteristics, action arena, and overall outcomes, the framework acts as a “diagnostic tool” that investigates any subject where “humans repeatedly interact within rules and norms that guide their choice of strategies and behaviors,” analyzing the “dynamic situations where individuals develop new norms, new rules, and new physical technologies” (Hess and Ostrom, Reference Hess and Ostrom2007). Institutions are defined as formal and informal rules that are understood and used by a community. Central to the IAD framework is the question “How do fallible humans come together, create communities and organizations, and make decisions and rules in order to sustain a resource or achieve a desired outcome?” Broken down into three core sections, a knowledge commons can be assessed by its resource characteristics (the biophysical–technical characteristics, community, and rules-in-use), action arena (institutional changes and the process of voluntary submitting artefacts), and overall outcomes. Specifically, for a knowledge or information commons, the IAD framework is useful, because it supports investigation into how resources are actually governed and structures the empirical inquiry to facilitate comparisons, while avoiding unwarranted assumptions related to particular theories or models (Strandburg et al., Reference Strandburg, Frischmann, Madison, Strandburg, Frischmann and Madison2017). As part of the IAD framework, E. Ostrom identifies seven rules by which institutions could be analyzed (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005):

-

1. Position: The number of possible “positions” actors in the action situation can assume (in terms of formal positions, these might be better described as job roles, while for informal positions, these might rather be social roles of some capacity);

-

2. Boundary: Characteristics participants must have in order to be able to access a particular position;

-

3. Choice: The action capacity ascribed to a particular position;

-

4. Aggregation: Any rules relating to how interactions between participants within the action situation accumulate to final outcomes (voting schemes, etc.);

-

5. Information: The types and kinds of information and information channels available to participants in their respective positions;

-

6. Payoff: The likely rewards or punishments for participating in the action situation; and

-

7. Scope: Any criteria or requirements that exist for the final outcomes from the action situation.

In advancing the practical application of the IAD framework into new use cases, the framework has been adapted to create building blocks for developing a commons. E. Ostrom adapted her design principles into key questions to created actionable means for problem-solving (E. Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2005). Translating the IAD framework’s core sections of biophysical characteristics, action arena, and overall outcomes, McGinnis transposes these questions, abstract concepts, and analytical tools to a detailed study of specific policy problems or concerns (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis, Coleand and McGinnis2018). McGinnis encourages users of the framework and questions to adapt them in ways that best suit the applications to the factors deemed most important for understanding the research puzzle or policy concern that serves as the focus on researchers’ own work. A summary of McGinnis’ steps of analysis are:

-

1. Decide if your primary concern is explaining a puzzle or policy analysis.

-

2. Summarize two to three plausible alternative explanations for why this outcome occurs, or why your preferred outcome has not been realized; express each explanation as a dynamic process.

-

3. Identify the focal action situation(s), the one (or a few) arena(s) of interaction that you consider to be most critical in one or more of these alternative explanations.

-

4. Systematically examine categories of the IAD framework to identify and highlight the most critical.

-

5. Follow the information flow in each of these focal action situations.

-

6. Locate adjacent action situations that determine the contextual categories of the focal action situation. This includes: outcomes of adjacent situations in which collective actors are constructed and individual incentives shaped, rules are written and collective procedures established, norms are internalized and other community attributes are determined, goods are produced and inputs for production are extracted from resource systems (that may need replenishment), and where evaluation, learning, and feedback processes occur.

-

7. Compare and contrast the ways these linked and nested action situations are interrelated in the processes emphasized by each of your alternative explanations.

-

8. Identify the most critical steps for more detailed analysis, by isolating components of adjacent action situations that determine the context currently in place in the focal action situation(s), and that if changed would result in fundamental changes in outcomes.

-

9. Draw upon principles of research design or evaluative research to select cases for further analysis by whatever methods are best suited to that purpose.

When creating a knowledge commons, Strandburg et al. (Reference Strandburg, Frischmann, Madison, Strandburg, Frischmann and Madison2017) also mapped the IAD framework into research questions as a means to support the planning and governing process of a commons, including the interview process for gathering participants and turning those interviews into practical goals and objectives for commons governance. The knowledge commons has also been applied to privacy by considering Nissenbaum’s contextual integrity (Nissenbaum, Reference Nissenbaum2004) to conceptualize privacy as information flow rules-in-use constructed within a commons governance arrangement (Sanfilippo et al., Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Standburg2018). We return to this in the conclusion of this paper, by discussing potential implications for policy-makers of viewing privacy through an information governance lens.

An example of an information or knowledge commons is a university repository (Hess and Ostrom, Reference Hess and Ostrom2007). Developing a university repository requires multiple layers of collective action and coordination as well as a common language and shared information and expertise. The local community, academics and researchers, can contribute to the repository, as the more it is used, the more efficient the use of resources is to the university as a public institution. Others outside that community can browse, search, read, and download the repository, further enhancing the quality of the resource by using it. By breaking down large, complex, collective action problems into action spaces through the IAD framework and using E. Ostrom’s design principles for governing a commons, institutions and organizations can better meet the needs of those in the community, including how information, knowledge, and data can be used to serve the common good.

From a technological perspective, the open-source and open-software communities can also be seen as knowledge commons, where software are freely and publicly available for commercial and noncommercial uses. The software tools are also openly developed, and anyone is able to contribute. Organizations such as the Open Usage Commons (Open Usage, 2021) help project maintainers and open-source consumers have peace of mind that projects will be free and fair to use. Platforms such as Wikipedia and the Wikimedia Commons (Wikimedia, 2021) are public domain and freely licensed resource repositories that are open and can be used by anyone, anywhere, for any purpose.

E. Ostrom’s design principles and the IAD framework can support a data protection-focused data commons, because they encourage active engagement of data subjects and considerations of how data can be protected through the development process while increasing its value. The analysis steps, questions, and framework encourage iterative means of creating a commons and supporting the co-creation process. The IAD framework recognizes that the expectations, possibilities, and scope of information and data can be different, as more knowledge is included within the commons. These principles are also useful in considering data protection solutions, because they recognize that there is no-one-size-fits-all fix and support more flexible and adaptable ways of achieving the commons’ goals. Incorporating existing regulations and policies into the commons for data protection allows data subjects to find specific solutions to their challenges by developing a better understanding of the data protection landscape of the specific domain, collaborating with other data subjects or stakeholders to co-create individual data protection preferences, and be able to exercise their data protection rights with the support of the community that has been harmed.

2.4.2. Data commons

E. Ostrom’s commons framework has been applied to data commons which guard data as a CPR. Traditionally, such data commons focus on data distribution and sharing rather than data protection (Fisher and Fortmann, Reference Fisher and Fortmann2010). Research data commons such as the Australia Research Data Commons (2020; ARDC), the Genomic Data Commons (GDC; National Cancer Institute, 2020), and the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC; European Commission, 2019) all attempt to further open-science and open-access initiatives. The ARDC is a government initiative that merges existing infrastructures to connect digital objects and increases the accessibility of research data. The National Cancer Institute also has a GDC that is used to accelerate research and discovery by sharing biomedical data using cloud-based platforms. With a research-oriented focus, the GDC does not house or distribute electronic health records or data it considers to be personally identifiable but still had safeguards against attempts to reidentify research subjects (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Ferretti, Grossman and Staudt2017). In Europe, the EOSC is a digital infrastructure set up by the European Commission for research across the EU, with the aim to simplify the funding channels between projects. The EOSC was inspired by the findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable principles (Wilkinson et al., Reference Wilkinson, Dumontier, Aalbersberg, Appleton, Axton, Baak, Blomberg, Boiten, Bonino da Silva Santos, Bourne, Bouwman, Brookes, Clark, Crosas, Dillo, Dumon, Edmunds, Evelo, Finkers, Gonzalez-Beltran, Gray, Groth, Goble, Grethe, Heringa, Hoen, Hooft, Kuhn, Kok, Kok, Lusher, Martone, Mons, Packer, Persson, Rocca-Serra, Roos, Schaik, Sansone, Schultes, Sengstag, Slater, Strawn, Swertz, Thompson, Lei, Mulligen, Velterop, Waagmeester, Wittenburg, Wolstencroft, Zhao and Mons2016) and aims to become a “global structure, where as a result of the right standardization, data repositories with relevant data can be used by scientists and others to benefit mankind” (European Commission, 2019). While these frameworks recognize that the information and knowledge are collectively created, their implementations are hierarchical and top-down, as they were created through structured committees, serving as a data repository platform that enables research reproducibility (Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Heath, Murphy, Patterson and Wells2016). As a result, they may have limited input from archive participants, repository managers, or public consultation processes and do not take E. Ostrom’s principles into account. Additionally, given the goals and objectives of these commons, by nature, they prioritize data sharing, data curation, and reuse, over data protection. While these data commons can be fruitful for furthering research and opening up data for reuse, they do not take into consideration the data subjects that created the data in the first place, as most data stored in these commons are not considered personally identifiable information. As a result, existing data commons alone are insufficient for protecting personal data, as they are designed without data subjects’ personal data in mind.

2.4.3. Urban commons

While data commons may not incorporate data protection principles, some data commons frameworks applied to urban environments and urban commons have been created in an attempt for governments to take more responsibility over their citizens’ personal data (European Commission, 2018). These commons are important for the development of data commons and data protection-focused commons, because they contrast other models that result in the datafication and surveillance of urban environments, such as the Alphabet Sidewalk Labs projects in Toronto (Cecco, Reference Cecco2020) and Portland (Coulter, Reference Coulter2021), both of which were scrapped due to concerns about the consolidation of data within big technology companies, lack of transparency about how public funds were to be used, and lack of public input during the development process of these smart cities. In contrast, in urban commons environments, resource management “is characteristically oriented toward use within the community, rather than exchange in the market” (Stalder, Reference Stalder, Hart, Laville and Cattani2010). An urban commons represents resources in the city that are managed by its residents in a nonprofit-oriented and pro-social way (Dellenbaugh-Losse et al., Reference Dellenbaugh-Losse, Zimmermann and de Vries2020). It is a physical and digital environment that aims to better utilize an urban space for public good, formed through a participatory, collaborative process. Urban commons aim to increase the transparency of how city data are used and provide accountability should users and data subjects want their data withdrawn. For example, the European projects DECODE (European Commission, 2018) and the gE.CO Living Lab (gE.CO, 2021) both encourage citizens to be part of a collaborative process in creating communal urban environments that better represent the community. The DECODE data commons project “provides tools that put individuals in control of whether they keep their personal information private or share it for the public good” (European Commission, 2018) with the focus on city data in four different communities. The project not only created an application to support user control over their data (DECODE, 2020), but also produced documents for public use on community engagement, citizen-led data governance, and smart contracts to be applied to urban environments. The outcomes from the project have been applied to local European projects such as Decidim in Barcelona to create open spaces for democratic participation for cities and organizations through free, open-source digital infrastructures (Decidim, 2021). Furthermore, the DECODE project continues to shape the EU’s direction when it comes to policy-making for digital sovereignty (Bria, Reference Bria2021). The gE.CO Living Lab creates “a platform for bringing together and supporting formal groups or informal communities of citizens” (gE.CO, 2021), who manage co-creation spaces and social centers created in regenerated urban voids. The Lab’s aim is to foster “sharing and collaboration between citizens and establish a new partnership between public institutions and local communities, setting forth new models of governance of the urban dimension based on solidarity, inclusion, participation, economic, and environmental sustainability” (gE.CO, 2021). As cities become more digitally connected and more data are being collected from their citizens, an urban commons increasingly focuses on data both in determining how information and resources can be created and shared within a community and focusing on citizens’ personal data.

2.5. A data commons for data protection

More recently, organizations focusing on data governance and data stewardship have explored the use of a commons for data with applications specifically to data protection. The Ada Lovelace Institute has identified a data commons as a means to tackle data-related issues, such as consent and privacy, by mapping E. Ostrom’s principles to specific GDPR principles and articles (Peppin, Reference Peppin2020). The focus on creating a commons for data draws attention to the sharing and dissemination of information and expertise, as it relates to data, encouraging a more open and collaborative environment. By sharing the data that are available, responsibilization can be limited, where resources are pooled for collaborative decision-making instead of individuals having to understand everything on their own. This can minimize the impact of data-related harms as a preventative method rather than a reactive one. In developing the practical basis for developing new forms of data stewardship through a commons, the Ada Lovelace Institute has also compiled a list of commons projects, mapping them to E. Ostrom’s principles and creating a set of design principles for data stewardship (Ada Lovelace Institute, 2021d). More broadly looking at the value of data, the Bennett Institute and Open Data Institute have mapped E. Ostrom’s principles to examples of how our data are used in a data-driven economy, highlighting the need to “provide models for sharing data that increase its use, capture positive externalities, and limit negative ones, so we can maximize the value of data to society” as well as include trustworthy institutions that together govern who can access what data “in accordance with the social and legal permissions they are given” (Bennett Institute for Public Policy and the Open Data Institute, 2020).

The data commons model for supporting data protection can be beneficial compared to existing data stewardship frameworks where data subjects and protecting personal data according to their preferences is prioritized. While data protection has been considered as part of the commons process, including data subjects and their communities is not seen as a requirement when considering how their personal data can be protected. Creating a data protection-focused data commons could help identify how much understanding and control data subjects have over their personal data and support them in choosing their data protection preferences. It can also support wider policy goals that reflect the principles, aims, and objectives as laid out by existing data protection and data-related rights through greater transparency, co-creation, and recognizing data subject agency. The consideration of supporting community norms through a commons can help ensure that the model is bottom-up in its design and iterative changes. Compared to existing data stewardship frameworks, a commons for data protection does not require the creation of a new legal framework, but rather operates within the current data infrastructures and norms used by data subjects while acknowledging the limitations of existing laws, technologies, and policies that steward data. For example, unlike the data cooperatives that require an organization to incorporate and register as a cooperative, the commons can be deployed through sociotechnical and policy means into existing institutions to establish duties between stakeholders without requiring the adoption of legal stewardship requirements. This makes the commons and those who participate in it more mobile and able to react to the changes in how companies use personal data as well as data breaches. Thus, the focus on data protection as part of the data commons shifts data protection responsibilities away from the individual alone and to communities, where knowledge, expertise, and experiences can be pooled together to identify working solutions. Data subjects are able to join a specific data protection-focused data commons if they identify with the commons’ aims for the protection of personal data that refers to them as individuals or a group in which they are a part of. Those who participate in a data commons should respect the community norms which they can also help create. The data commons should not only be considered as a form of personal data sharing, but rather be used as a community resource that facilitates the personal and collective aims of protecting personal data, where the sharing of personal data and data rights is not necessarily required. Anyone can leave the data commons any time they wish. Although personal data are still kept personal and private, the collaborative nature of sharing, discussion, and advising on data protection problems opens up potential options for everyone to support informed decision-making and achieving data protection preferences through a data commons. Those in the commons can then choose to act independently or as a group, whichever best suits their personal preferences. The framework can also support the remedy of potential data breaches through the exercise of data subject rights and the coordination of data rights efforts within the community. For example, a data protection-focused data commons can support the “ecology of transparency” that emphasizes the collective dimension of GDPR rights for social justice (Mahieu and Ausloos, Reference Mahieu and Ausloos2021). The creation of a data protection-focused data commons can support policy goals that further the principles, aims, and objectives as laid out by data protection law through greater transparency, co-creation, and recognizing data subject agency without necessitating specific legal or technological requirements outside of community norms.

In previous work, we identify how a data protection-focused data commons can help protect data subjects from data protection harms (Wong and Henderson, Reference Wong, Henderson, Ashley, Whyte, Pitkin, Delipalta and Sisu2020). A data protection-focused data commons allows individuals and groups of data subjects as stakeholders to collectively curate, inform, and protect each other through data sharing and the collective exercise of data protection rights. In a data protection-focused data commons, a data subject specifies to what extent they would like their data to be protected based on existing conflicts pre-identified within the data commons for a specific use case. An example use case would be online learning and tutorial recordings. For students (as data subjects), participating in a data protection-focused data commons allows them to better understand their school or university’s policy and external organizations’ guidance when it comes to collecting, processing, and sharing their personal data related to online learning, allow them to ask questions to experts, raise any questions about data protection to staff, review their consent decisions on whether to agree to tutorial recordings, and exercise their data protection rights should they wish to do so. Unlike existing data commons, the data protection-focused data commons focuses specifically on protecting data subjects’ personal data with the ability to co-create and work with other data subjects, while still being able to directly exercise their data subject rights. It simplifies the data protection rights procedure by including information, instructions, and templates on how rights should be collectively exercised, giving data subjects an opportunity to engage with and shape data protection practices that govern how their personal data are protected. For example, an online learning data commons may only focus on how students’ personal data are collected, used, and shared for ways to enhance learning. In contrast, an online learning data protection-focused data commons would also directly provide students with the related university policies or best practices, give students the ability to decide whether they consent to certain collection and processing of data, and support them to exercise their rights to the university’s data protection officer.

2.6. Research questions

As data subjects are often left out of the data protection process, they lack a meaningful voice in creating solutions that involve protecting their own personal data. Although a co-created and collaborative commons has been considered for managing and protecting data, commons principles have not specifically been applied to establish a data commons that focuses on data protection and with the objective of protecting data subjects from data-related harms.

Our aim for this work was to find out more about how existing commons were created, and what the associated challenges were related to data protection, and support the implementation on a commons. To investigate those aims, we conduct interviews with commons experts to identify the challenges of building a commons and important considerations for a commons’ success. From their contributions, we aim to develop a practical framework for including data subjects in the data protection process through a data commons and create a checklist to support policy-makers in implementing the data commons.

We established four research questions to explore whether using data subject rights and data protection principles to support a data protection-focused data commons is suitable both in theory and in practice:

RQ1: How, if at all, did interviewees work on identifying and solving data protection challenges?

RQ2: How can the challenges of implementing a data commons best be overcome, specifically for data protection?

RQ3: What do interviewees think could be done better in terms of creating a commons?

RQ4: Is a commons framework useful for ensuring that personal data and privacy are better protected and preserved?

3. Methodology

We developed our study in three phases: identifying relevant commons and key informants, writing the interview questions, and conducting the interviews.

3.1. Identifying relevant commons and key informants

Urban commons and data commons applied to urban cities were identified as the most relevant to establishing a data protection-focused data commons, because they represent a commons model that considered data protection and privacy. The relevant commons identified for answering our research questions were found through conducting a literature review on recent self-described urban commons and data commons. The commons selected all used the commons to describe their work and their aims, with goals that emphasize co-creation and collaborative work with the community. As all authors reside within the jurisdiction of the GDPR, an online search was conducted to identify European commons only.

Once the commons were identified, experts were chosen based on their expertise and experience in creating and developing an urban commons or data commons, and were contacted via e-mail. To ensure that we had a fair assessment of the commons development process, when contacting experts, we made sure that they had different levels of expertise, different roles and responsibilities within commons development, and represented different communities. The size and scope of each commons project was also as varied as possible in order to better understand how similar or different commons challenges may be throughout development.

Interviews were conducted to contextualize the role of the commons from different stakeholder perspectives and provide useful information into potential challenges in the development process. Interviewees were told that this study contributes to our wider work on establishing a data protection-focused data commons to achieve better data protection for data subjects regarding the processing of their personal data in a collaborative way and allows them to co-create data protection policies with other data subjects and stakeholders, examining how information rights can be supported through a commons.

Prior to the interview, key informants were given a participant information document and a consent form for them to sign and return. Once the interview was complete, a debrief was sent to the participant with more information about their data rights and our broader research.

3.2. Writing the interview questions

Key informant interview methods were used to design the interview, with a semi-structured format to encourage discussion around the commons. The questions aimed to answer the research questions identified in Section 2.6, augmenting what data protection lacks to explore the relevance of the creation of a data protection-focused commons and whether information rights can help with finding a solution. The interview method and questions are included as part of the Supplementary Material of this article.

In responding to the research questions identified in Section 2.6, we asked the experts those questions and supplemented them with the following questions, before engaging in further discussion:

RQ1:

-

• How did you and the project team come about identifying your project aims and what were some of the problems or challenges you considered during that process?

-

• What stakeholders did you interact with to solve some of these challenges?

RQ2:

-

• How did you go about solving the challenges identified?

-

• Were there problems or challenges during the project that you did not expect related to data?

RQ3:

-

• What do you think are/were the successes of your role in the commons?

-

• How was this success achieved?

-

• What do you think are/were the limitations of your project as a commons?

-

• Is there anything you would do differently?

RQ4:

-

• How do you think data and data protection can be best represented in the commons and in commoning?

-

• Can data subjects and participants’ involvement in creating the commons support better data protection practices?

-

• What do you think is the ideal commons for data? Do you think it can be achieved? If so, how?

3.3. Conducting the interviews

Interviews were conducted either over the phone or conferencing software, such as Skype, jit.si, or GoToMeeting, based on the interviewees’ preference. All interviews were conducted by the first author between March and November 2020 and lasted up to 1 hour. All interviews were recorded with the interviewee’s consent. Once each interview was completed, audio recordings were placed into the MaxQDA qualitative data analysis software for immediate transcription and pseudonymization. Once the transcription was finished, audio recordings were deleted.

4. Analysis

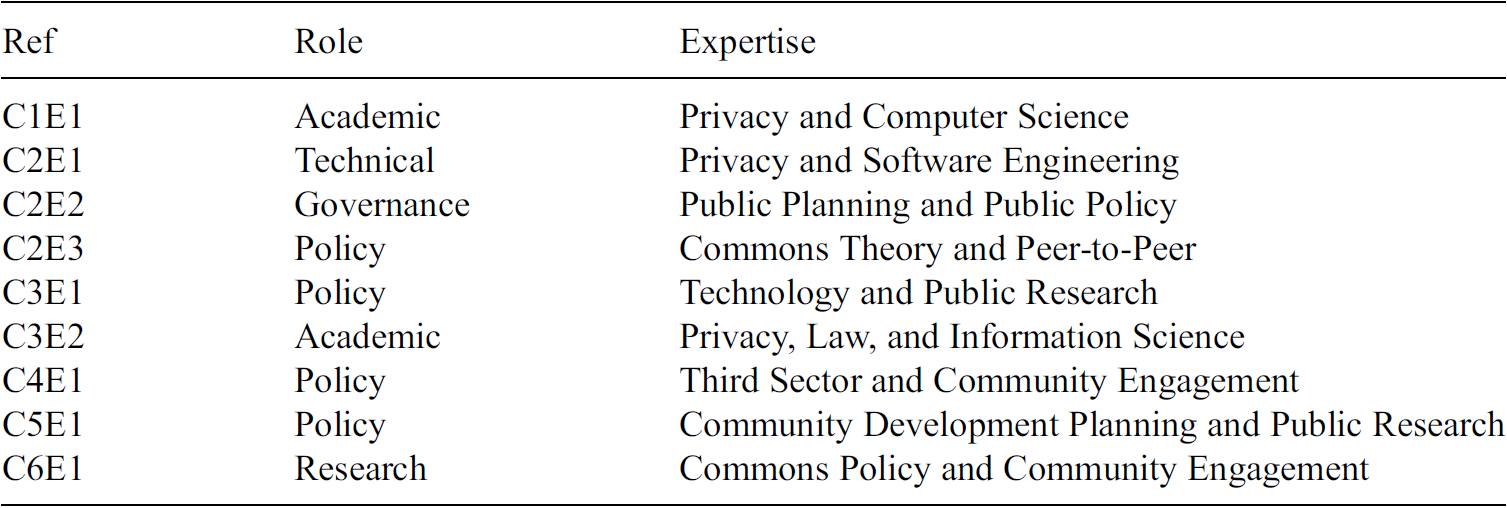

Nine experts across six commons were interviewed. The size, number of participants, and stakeholders varied across the commons, with three interviewees based in the Netherlands, two in the United Kingdom, one in Belgium, one in Germany, one in Italy, and one in Spain. Their roles and specialisms are listed in Table 2. Reference Cx denotes the commons they contributed to, and Ex denotes the expert. Role characterizes the experts based on their responsibilities within the commons. Expertise describes their main contribution toward the commons.

Table 2. List of interviewees representing their commons project, role within the project, and their expertise

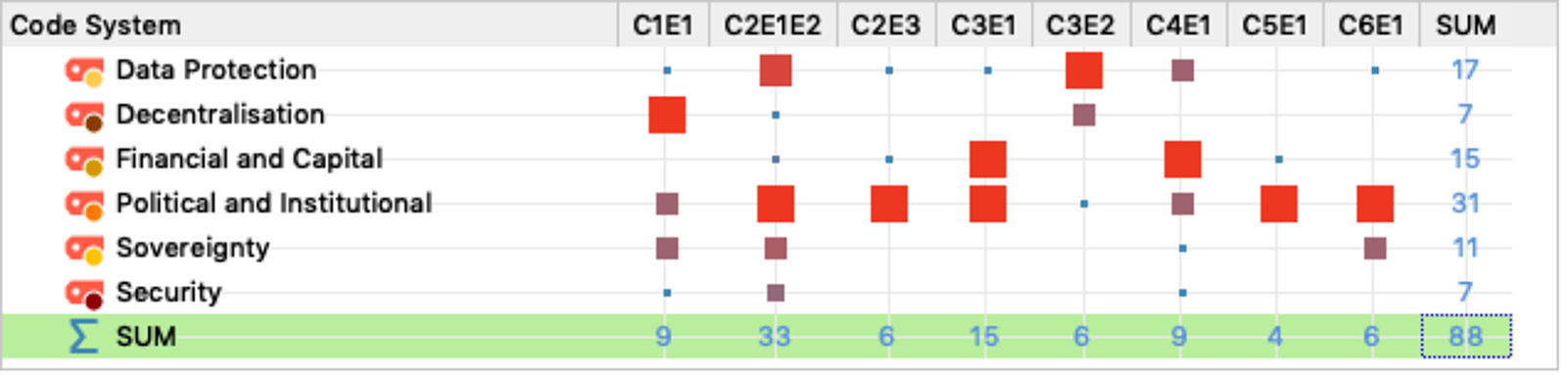

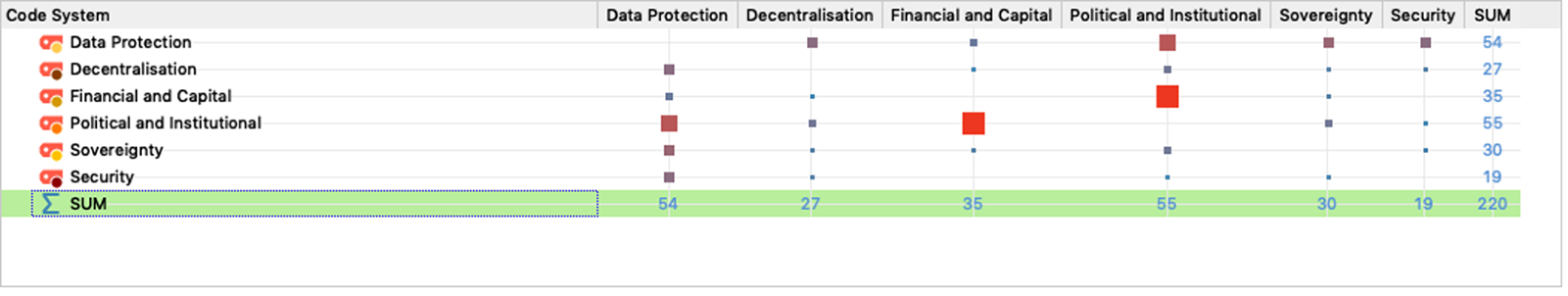

Using MaxQDA, codes and tags were used to identify patterns for preliminary transcript analysis, identified in Figures 1 and 2. Although the interview centered around developing a commons and challenges regarding data protection, discussions around people and their interaction with others can be seen as the most prominent topic mentioned by experts. In particular, human-centered themes, such as political and financial relationships, were mentioned the most. Based on these characterizations, main themes were drawn out and expanded upon from the interviews. For our interview transcript analysis, we present our results in four sections: identifying data protection challenges, overcoming data protection challenges, improving the commons, and building a commons for data protection. We found that political and institutional barriers when it came to creating a commons were the most difficult to tackle, underlying how data and data protection are not necessarily seen as something that could be perceived as a commons. While data protection was discussed as part of the commons development process, there were limited applications to wider data protection principles such as those relating to informing data subjects about their rights and the ability to exercise those rights against data controllers. All experts identified limitations within their own area of expertise, suggesting that these limitations, whether in law, technology, or policy, need to be identified within the commons in order to find better data protection solutions. Although the decision to use a commons was to provide certain levels of control and transparency of how data were collected, used, and processed, financial restrictions limited the potential impact of the commons framework and the extent to which a commons could scale. Interviewees further mentioned that working with stakeholders of different backgrounds helped everyone better understand how a commons should be implemented and could be beneficial for reaching data protection goals. Our interview findings are addressed thematically below by each research question.

Figure 1. Code matrix created from interview transcripts with all experts. Manually coded themes related to identifying problems and challenges were tagged, and their frequencies are visualized based on how often they were discussed by interviewees. The most prominent challenges are those related to politics and institutions (31), followed by data protection (17), and financial and capital (15) related issues.

Figure 2. Code relation matrix created from interview transcripts with all experts. Manually coded themes related to identifying problems and challenges were tagged, and their relationship with other themes are visualized based on how often they overlap, demonstrating how certain challenges are linked together. The most prominent relationships are political and institutional–financial and capital as well as political and institutional–data protection. Data protection issues also demonstrate some overlap with other problems and challenges more generally.

4.1. Identifying data protection challenges

From the interviews, the experts identified data and data protection challenges related to the commons based on their own role-specific experiences. These challenges include the difficulty establishing the scope of the commons regarding data and data protection, assessing how the commons can be beneficial to those who participate, and determining the value of data included as well as the data protection benefits.

First, in identifying the data protection challenges within commons projects, interviewees mentioned that the main aims of the commons were often provided by the project coordinators. The experts themselves only had partial input on the scope of the commons and how the commons was to be defined. An interviewee in a technical role said that following their core commons aim: “The most important challenge there was to make it decentralised” (C1E1). Another interviewee elaborated that: “Essentially what [the coordinators] wanted was, they realised that this [issue] poses a threat to [users’] privacy and they wanted us to build a system from the same dataset” (C2E2). However, it was clear to some experts that data and data protection challenges would only more clearly emerge once the foundation of the commons was established alongside other stakeholders due to the nature of commons building. One interviewee said: “The project was, we have these technologies, we do not know how these are going to be because we have not built it yet” (C2E1). Another interviewee said: “[One of the challenges is] striking a balance between openness and protection … and then just institutionalising that with advanced ICT” (C2E3). As a result, what the precise scope of the commons is needs to be flexible to accommodate changes during the development process and incorporating participant input. This includes being open to changes when it comes to how data are collected and managed within the commons itself.

When discussing the benefits of a commons to data subjects for protecting their personal data, there is a role of responsibility from experts to communicate the options for protecting personal data: “We played a role of coordination, and interaction with data subjects and data protection officers” (C3E2). Another interviewee said that participants in a commons should understand that they have a real ability to have autonomy and sovereignty over their personal data, where the commons can support their preferences by operationalizing this control: “in order for the data commons to work, you need to be able to give citizens some kind of control over their data, and give them, some kind of like, choice of what the data was going to be used for or not used for” (C1E1). Beyond the challenges laid out by project coordinators, interviewees also mentioned that there were data protection challenges that go beyond the practical creation of the commons and included theoretical, philosophical, and psychological aspects of people’s relationship with privacy. One interviewee summarized this eloquently: “So essentially three challenges: Money and difficulty in the social side, distributing the technology, and the philosophical who owns divulged data in a community side” (C2E1). Wider socioeconomic issues surrounding data and Internet access also need to be addressed when considering and implementing a commons framework: “The first thing I became aware of is the inequality in our access to the internet” (C4E1). One interviewee suggested that rather than considering the commons framework as something put on top of a community, think about a data commons as intrinsically part of community collaboration: “Digital space is infinite, we can have an infinitely large number of people in it, but we are still biological beings, we are still constrained by our biology and our grey matter up here. We can still only really build closed connections to this relatively small number of people. The question is not, in my opinion, how can we make commons all over the place, but more how can we bring together this biological and digital realities to optimise what is happening” (C6E1). While the commons itself may be valuable in terms of increasing accessibility to data and knowledge, it must be managed in a way that is accessible and easily understood for data subjects in order for the commons to be successful.

In the period in which the interviews were conducted, the COVID-19 pandemic was taking place, and so in consideration of the data protection and wider data-related challenges, analogies related to the pandemic were used. One interviewee explained how tensions exist when it comes to building a commons and considering data protection through the public or private sector, challenging existing norms when it comes to the use of our personal data: “We need to understand that we are giving all this information to the private sector to run our lives or to help us run our lives. This used to be delegated to the public sector so let us think about it or at least discuss about it, and see which model we really want because when something happens, like coronavirus nowadays, no one is looking for answers in the private sector but looking in the public sector. So I think a lot of reflection needs to be done in this and a lot of dialogue with the citizens and a lot of speech needs to be there” (C2E2). In considering political and institutional barriers, one interviewee shared how a commons framework could be useful for opening up data and resources in a meaningful way: “You have austerity destroying the public health infrastructure for a number of years, we have no valves, no ventilators, no masks, no protective equipment, and you see a mass of peer production groups that seek to solve these issues right? It is dialectic between the mainstream systems and increasing fault lines and then people self organising to find solutions beyond those bottlenecks basically” (C3E1).

4.2. Overcoming data protection challenges

According to the experts, establishing relationships with data subjects and developing trust in both the commons framework and those who created the framework was important for the commons’ success, particularly regarding personal data and data protection. While many of the commoners were engaged with their specific projects, transparency and clarity in the process of contributing to the commons can foster an environment for engagement to achieve a better commons outcome for individuals and groups.

One aspect is creating trust and establishing positive relationships between those who have an understanding of the data commons and data protection with those who do not: “The main problem was trying to be careful in understanding each other in achieving the goals but it was a cultural problem when you interact with different people from different backgrounds, and that’s a problem you have working with different people” (C3E2). Another aspect is bringing the community together within the commons. One interviewee said: “Two things were really striking, the first one is this binary process where either the user trusts you or does not trust you. But once they trust you, they give you everything. This is the direct consequence of, you know when you accept the terms and conditions of the services, that’s the same way” (C2E1). Another interviewee further explained: “Other than the legal constraints [surrounding data protection and privacy, we did not have any concerns that were raised]. This is one of the things that is really interesting and I think it is based on the trust. You have this social solidarity and there is this implicitly trust. If you break that trust, you are done” (C6E1). This suggests that all stakeholders within the commons should feel that they are being respected and treated as experts bringing in their own experiences, whether that may be knowledge, perspective, or personal anecdotes regarding their data.

Regardless of the use case of the commons, it is important to understand community concerns, applied both to data protection and other issues. For data protection, this includes recognizing the limitations of existing regulations and legal frameworks, such as the GDPR. One interviewee said: “[Although, legally, you can ensure the process of deletion is followed,] you cannot tell people to forget something and they will forget. It was also something we realise with the GDPR law and our legal experts also discussed that” (C2E1). These legal challenges regarding data protection also need to be considered throughout the commons development process, as Interviewee C3E2 explained the role of their team was to “deal with legal issues related to the goals of the project, fostering the making of the digital commons including personal data.” In order to overcome these challenges, input is needed from the community to assess the benefits and risks to the use of their personal data. However, Interviewee C5E1 explained that although the community was willing to engage, they felt unable to do so, either because they did not know how or because they had been approached in a manner which did not appeal to them. The type of involvement related to the sharing of citizens’ data-related worries and the data protection issues they were currently facing to enable their data protection rights to be enforced. Another interviewee explained that the commons framework is useful for unpacking the sociopolitical challenges that impact the community, rather than specifically seeking a technological solution: “We have just used the term [data commons] to introduce [stakeholders] to this kind of thinking to immediately hear them out and how they feel about the data society, about the smart city discourse etcetera and see within their context, in mobility projects in certain neighbourhoods, or energy transition, how they feel they want to deal differently with these technologies and how with urbanity or neighbourhood initiatives” (C2E3). As a result, when overcoming data protection challenges within a commons, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the law, technologies, and data. The commons should support different methods for allowing data subjects to choose their own personal data protection preferences.

4.3. Improving the commons

When discussing the usefulness and effectiveness of the commons, some interviewees expressed doubts. One said: “I’m not entirely sure that [the project coordinators] actually achieved [their goals] in a reasonable sense because at some point there were too many challenges to resolve that and we took some short cuts in order to reasonably put something forward for the demo so there were lots of privacy issues that had to be solved later” (C1E1), emphasizing the importance of timely development. Even in a commons, other stakeholders may be prioritized over data subjects, particularly when external financing and funding is involved: “I often see the potential in people and areas in the project and then I have a hard line of what can and cannot be done and what the money was allocated for. So within our remit as an organization moving forward, it will be a huge conversation with the much higher ups than me about how do we deliver on our goals as set out in our original funding in a meaningful way that means that we are truly kind of, and I hope we have those conversations with people that are left out the most and working their way down to people who have access to things easily” (C4E1). As a result, when establishing a successful commons, the scope of a specific commons is key in order to ensure that it is sustainable and balances the trade-offs between transparency and formalization with more fluid and iterative ways of working: “One of the other risks that came about was this transfer from a small project to a bigger project. These like growing pains are always difficult and the new definition of roles, the formalisation of rules, is really really interesting and also when it starts to make money. When there starts to be something to have, something to gain, something that people want then the interpersonal relationships really change and that can be a real risk in particular with group cohesion” (C6E1). As part of the development process, if there is no community consideration, policy can be negatively impacted. From an interviewee, over 60% from a group of 50,000 people surveyed had never been consulted before: “It is very concerning at a policy level where we are trying to make consulting decisions based on what the community want or what the stakeholders want or what the users want when the people we are hearing from are entirely unrepresentative of the local community” (C5E1).