Edward Frank Zigler was a legendary psychologist who over his 60-year career moved forward the fields of developmental psychology, child development, education, social policy, and prevention to new and better frontiers. He and everyone who crossed paths with him should be proud of what was accomplished, and how Ed, as he liked to be called, left this world in a better place for young children and families, and for everyone who cares about the future.

Ed was not only a great scientist but went a step further by taking research ideas and evidence and translating them into concrete actions to improve the lives of children and families, especially for those in adversity. He did this throughout his career, as shown by his work and leadership in the first federally sponsored preschool program Project Head Start, for which he is most known, and also for the next-generation Early Head Start program serving children from birth to 3 years of age, Parents as Teachers, and the School of the 21st Century model he developed.

Ed had a social action agenda based on the integration of interdisciplinary research and policy to solve social problems. A great influence on his broad view of psychology's mission and the critical need for a science-based approach was his leadership in the early 1970s as the first Director of the US Office of Child Development (now Administration for Children, Youth and Families) in the Nixon administration and Chief of the US Children's Bureau. Ed oversaw Head Start and many other family service programs, and established a strong foundation for research, next-step efforts, and program improvements that continued for the next four-and-a-half decades.

Overview

The goal of this article is not to revisit or analyze the most well-known contributions of Edward Zigler. This is covered quite well in other articles in the special issue and elsewhere (Burack & Luthar, Reference Burack and Luthar2020; Kim & Pevner, Reference Kim and Pevner2019; Yale University, 2019; Zero to Three, 2019). I believe what Ed accomplished is much more than this. They all support the main theme of his life and career: defining and using science in all dimensions as a direct form of social action to improve society. He stated this unbending principle throughout his career in writings and actions. For example, in summarizing the research history in child development, he noted “basic and applied research are not different enterprises but are highly synergistic. These decades of rigorous basic research unquestionably expanded our knowledge of human development, but the ultimate purpose of this knowledge gathering should be to improve the human condition” (Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006; p. 347).

My purpose is to dig deeper and reflect on several of Ed's contributions that are greatly underrated and under-appreciated in the larger scope of his work and in the field. These include (a) historical analysis of Project Head Start, (b) conceptualization and analysis of motivation as a core influence of program impacts, (c) development of preschool-to-third-grade interventions and school reforms, and (d) critical analysis of theory, research, policy, and practice. They deserve to be acknowledged and discussed more directly than they have before. I also believe they are major contributions in their own right. His authoritative knowledge on early childhood development aligned nearly perfectly with innovation in program development and policy prescription, but also by realism about what can be accomplished by a single program.

In an important reminder to the field, he explained:

Development is a continuous process; experiences at any given age are affected by and built on experiences that have come before. Thus intervention at later stages of life can no more wipe out a history of disadvantage than can a brief early intervention inoculate a child against continuing disadvantage. (Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983, p. 898)

Foundations of Influence from the 1960s to the Present

Although Ed (I use his preference and Dr. Zigler interchangeably) was a member of the Head Start planning committee (Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997), he was not the founder of the program. Sargent Shriver has this honor, as Ed has noted, and was also the creator and first director of the US Peace Corps (Zigler & Muenchow, Reference Zigler and Muenchow1992; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco2010). Ed was without a doubt, however, the chief visionary and champion of Head Start during its formative stages and strongly influenced its continuing improvements. Established by Sargent Shriver, who directed the Johnson administration's War on Poverty initiatives, and chaired by pediatrician Robert Cooke, the planning committee was a multidisciplinary group spanning all human service fields. It also included, among other scholars and leaders, Urie Bronfenbrenner, psychologist Mamie Clark, whose research was influential in the landmark 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court Ruling, and Bank Street College of Education President John H. Niemeyer.

Over the course of his career, Ed was a key intellectual leader of the country's early childhood program movement, which is today enrolled in near universally. He also dedicated his life to helping to ensure that children and parents growing up in poverty as well as having developmental disabilities enjoy the same opportunities and benefits in education and society as everyone else. This is a hallmark of Head Start and other programs and policies Ed worked on so persistently. Child maltreatment prevention, family support programs, and child care also were key foci of research and policy to strengthen the well-being of parents and children.

In recognition of the high value he placed on evidence-based policy, a lesser known fact is that in the mid-1970s Ed, along with Francis Palmer and Edith Grotberg, spearheaded the creation of the landmark Consortium for Longitudinal Studies (1983) run by Irving Lazar at Cornell University (Zigler & Muenchow, Reference Zigler and Muenchow1992). This project remains among the best evidence of the benefits of early childhood enrichment. Ed and Victoria Seitz's own New Haven Head Start/Follow Through project, Susan Gray's Early Infancy project, and the High/Scope Perry Preschool program were also a part. Many other programs and research initiatives were developed in which Head Start and the key importance of evidence was a catalyst, such as Project Follow Through, Parent Child Development Centers, Project Developmental Continuity, the Child Development Associates Program, Services for Handicapped Children, Home Start, and Child and Family Resources Centers (Zigler & Freedman, Reference Zigler, Freedman, Kagan, Powell, Weissbourd and Zigler1987a).

I am certainly proud to have known him as a friend and colleague for three decades, worked with him, shared and discussed ideas about professional and personal matters, and above all benefited from his wisdom about life and how to make the world better for children, families, and citizens. I know Ed would be deeply saddened by the health, economic, and social crises now facing the country as a result of coronavirus/Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the social unrest concerning widespread police brutality and racism against Black Americans and other people of color (Berwick, Reference Berwick2020; Williams & Cooper, Reference Williams and Cooper2020). Ending not only poverty but racial discrimination at all levels of society were core goals of the 1960s’ civil rights movement and the War on Poverty. As then, broad and multifaceted policies, program, and laws are needed and there is increased urgency to eradicate all structures of inequality and discrimination. Ed would be an active and full partner in this continuing struggle.

Reflections on Core Beliefs and Character

Before discussing these contributions, it is important to reflect on the core beliefs and principles upon which Ed led his life. These greatly determined his professional accomplishments, and the advances in science and social progress I discuss below. First, Ed Zigler was a person of high and unbending integrity. This was easy to spot in meetings, conversations, and nearly every forum in which I encountered him. Ed presented his views and perspectives with evidence without regard to who he was talking to and what she/he may have wanted to hear. This integrity and the fact that he stuck to the scientific facts, realism, and future needs rather than past failures is what made him so effective as an advisor to governments, presidents, governors, and many organizations.

His personal and professional integrity was illustrated well in his appointment in 1970 as the first Director of the US Office of Child Development by President Richard Nixon. This was the office set up to run many of the innovative programs of the War on Poverty within Sargent Shriver's Office of Economic Opportunity. Although I was not privy to his personal political views, it was clear from discussions that he was not in the Republican party. He took this important federal position purely as a force of good for children and families. Moreover, this was well before the Watergate scandal, and there were high expectations that President Nixon and his administration would prioritize child and family issues. They did in the first three years. Ed's critical role in the development of the Family Assistance Plan of 1972 (revised from 1969) and the Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971 legislation – the latter of which would have created and funded a national system of child care for working parents – nearly became law until President Nixon suddenly reversed course and vetoed the bill (Zigler & Muenchow, Reference Zigler and Muenchow1992; also see Roth, Reference Roth1976 for an historical account). Nevertheless, Ed's stature only increased after serving in the administration, as he effectively balanced the interests of children and science with the politics of the times.

Second, Ed was a truly honest person. This could, of course, make his sometimes critical views unpleasant to hear, and have positive or negative consequences to others or himself. As one example, in an early 1990s presentation on the need to improve Head Start quality, which was reported in a New York Times article, Ed commented that “only about half the nation's 1,400 Head Start programs are of high quality, while about a quarter are ‘marginal’ and the rest are so poorly run they are doing virtually nothing to help children” (DeParle, Reference DeParle1993). This was expanded upon in a Los Angeles Times interview where he stated in response to whether there is public understanding about how to expand the program: “No. They've [public] heard so much about Head Start. They think that Head Start is a homogeneous program…they don't know that it's [1,400] programs: some great, some mediocre, some rotten.” However, he goes on to state: “what's bothering me is that other countries are making this kind of investment in their children and we are not. I think that what this is going to do in terms of our competitive posture down the track, over time, is going to be terrible” (Mills, Reference Mills1993).

These statements and others like it did not go over well with advocates or policy makers. Ed certainly felt bad about the fallout. Nevertheless, he was reinforcing what was widely known that the level of quality was too variable and needed attention. Federal reports on Head Start issued later that year and subsequently also identified problems related to program quality in many centers (US General Accounting Office, 1993, 1995).

As another example, in 2004 Ed asked me to contribute a chapter on the current state of the economic returns of early childhood programs for a book on universal preschool he was working on. I agreed, and the feedback from the first draft was clear, direct, and highly critical. “What have I got myself into?” was a frequent refrain. Although I was taken aback by the extensive comments and need for improvement, Ed was correct in his recommendations for a more complete account. The final version was a comprehensive review that was unique in its coverage of the history of early interventions, model and large-scale programs, and recommendations for policy and research. His feedback helped turn a marginal chapter into one I now consider one of the best analyses of the growing field (Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds, Temple, Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006). The published book, which I discuss below as an underrated example, was one of the first on universal preschool (Zigler, Gilliam, & Jones, Reference Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006). One always knew where Ed stood on the issues, both research and policy. There were no hidden agendas.

Ed's criticisms and reflections, could also be self-directed. Recounting his consideration of being appointed Chief of the US Children's Bureau and Director of the Office of Child Development, Ed remarked, “In fact, I was surprised I was even being considered for the job because I was not affiliated with either party. In terms of management ability, I did not have the background to run a candy store much less a federal agency with a budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars” (Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco2010, p. 82). What a transition he had to make! Ed clearly understood this, but he had vision for how to proceed and strengthen the agency to improve children's lives. He also chose a strong team of day-to-day managers and lieutenants to help him be as effective as possible, including Saul Rosoff, Donald Cohn, Carolyn Harmon, Dee Wilson, and Harley Frankel (Zigler & Syfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco2010).

As a third core belief, although Ed was a developmental psychologist, he followed a unique, interdisciplinary blend of principles and scholarship from the traditional foundations of nature and nurture, intellectual development, early enrichment, family and social contexts and led to the intersection between science, social policy, and action. Although a developmental approach focused on young children and families was the common theme, Ed was a maverick and expanded the boundaries of developmental psychology to social action, which benefited greatly the next generation of scholars, analysts, and practitioners as well as society at large. He worked extensively in child care and family policy (Kagan, Powell, Weissbourd, & Zigler, Reference Kagan, Powell, Weissbourd and Zigler1987; Zigler & Lang, Reference Zigler and Lang1991), education and school reform (Finn-Stevenson & Zigler, Reference Finn-Stevenson and Zigler1999; Kagan & Zigler, Reference Kagan and Zigler1987; Zigler, Gilliam, & Barnett, Reference Zigler, Gilliam and Barnett2011), developmental psychopathology (Zigler & Glick, Reference Zigler and Glick1986), child maltreatment prevention (Kaufman & Zigler, Reference Kaufman and Zigler1987; Zigler & Hall, Reference Zigler, Hall, Cicchetti and Carlson1989), and mental retardation (Zigler & Hodapp, Reference Zigler and Hodapp1986; Zigler & Turnure, Reference Zigler and Turnure1964). He endorsed cost–benefit analysis as a method of evaluating programs earlier than anyone in psychology, and prior to most economists (Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983). From the beginning, he greatly valued Bronfenbrenner's (Reference Bronfenbrenner1989) ecological system theory, which was more influenced by anthropology, sociology, cross-cultural studies, and systems science than by psychology. The breadth of interests, scholarship, and their translation to programs and policy development and implementation was rare in the field at the time, and certainly not part of most graduate training programs – even today.

Partly because of early work on children with mental retardation, Ed emphasized adaptive competence in real-world settings and the value of motivation as instrumental to well-being rather than abilities measured by IQ tests. Ed was against the widely accepted belief in the 1950s and 1960s of the primacy of cognitive change in interventions:

I also did not share the then-popular vision that an early intervention program could permanently raise children's IQs. In fact, I was probably one of the few psychologists during that period who was skeptical of the whole idea that it is possible to raise IQs dramatically. I thought that instead of trying to improve children's intellectual capacities, we would be better off trying to improve their motivation to use whatever intelligence they had. (Zigler & Muenchow, Reference Zigler and Muenchow1992, p. 10)

Four Underrated Contributions

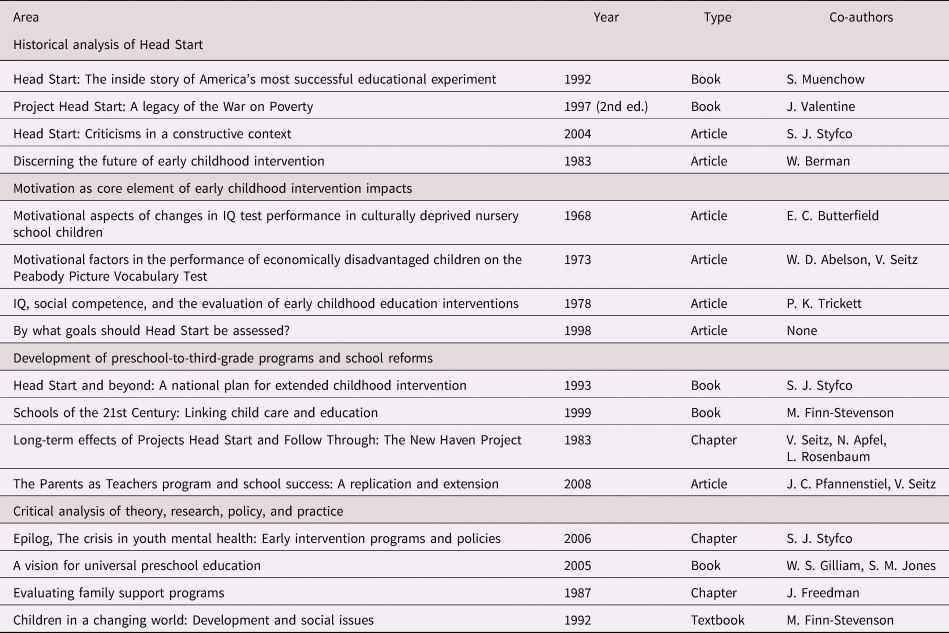

I discuss four key contributions: (a) historical analysis of Head Start, (b) conceptualization and analysis of motivation as instrumental to early childhood intervention impacts, (c) development of preschool-to-third-grade programs and school reforms, and (d) critical analysis of theory, research, policy, and practice. Representative publications are listed in Table 1, many of which I review below. Certainly, there are many more articles, reports, and books in these four areas of scholarship. Some of the articles may also support well-acknowledged contributions that are not underrated per se (e.g., pioneering child development and social policy, evaluating early childhood programs). There are other underrated areas (e.g., advisory roles, government service) that could be covered as well. For those who may believe that some of the contributions I discuss are not necessarily underrated in the field, I have a different view.

Table 1. Select articles, books, and reports representing four underrated contributions of Edward Zigler

Note: Reference section includes full citations.

A. Historical analysis of Head Start

As is well known, Dr. Zigler had a unique role in the creation of Project Head Start. He was among a distinguished, multidisciplinary group of scholars and leaders on the 1964 planning committee. Head Start opened as summer program in 1965 for 560,000 children, most of whom were 4-year-olds. He became a leading advocate, critic, and intellectual leader of the early childhood movement in the 1970s that continued throughout his life. What is much less known and greatly underrated, however, is his lucid and insightful historical analysis of the program from its development and during the following decades. This coverage also generalizes to most other early childhood interventions that began in the 1960s, which he also reviewed.

Head Start history is a story of developmental theory, nature and nurture, education, and family support but most importantly about social action through the enactment of laws and initiatives on a national scale to increase educational opportunity and community engagement. Dr. Zigler articulated this vision and agenda clearly and thoroughly (Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983; Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997), with the ultimate goals to eradicate poverty and racial inequality. Head Start was developed at the start of the civil rights movement and President Johnson's War on Poverty/Great Society era. Civil unrest was at a peak, and advocacy of new approaches for addressing an array of social problems was urgently needed. The term “War on Poverty” was coined by then Senator Hubert Humphrey (Humphrey, Reference Humphrey1964). Much of the vision for this national movement was created by President John Kennedy before his tragic death in 1963.

Coming after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 (which included the Head Start Act authorization), led to a series of economic, social, and community action initiatives that included in 1965: the Voting Rights Act, Social Security Act, which introduced Medicare and Medicaid, and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the latter providing aid to schools in low-income areas to promote innovative programs (Kaplan & Cuciti, Reference Kaplan and Cuciti1986; Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997). This federal aid to schools led to, for example, the second-oldest federally funded preschool program, the Chicago Child–Parent Centers (CPCs), which added school-age services in support of developmental continuity and a preschool-to-third-grade approach (P-3; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2000; Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple1998; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1971).

The best example of analysis of Head Start history is his 1992 book with Susan Muenchow Head Start: The inside story of America's most successful educational experiment (Zigler & Muenchow, 1992) (ZM hereafter; also see Hidden history of Head Start, Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco2010). The authors vividly describe the historical context and development of the program during a time of massive social change, with many personal insights about the role of the planning committee in relation to federal leadership, how research in child development was so influential, the early implementation of the program, and the handling of various controversies (e.g., the Westinghouse Head Start evaluation, the Jensen report in the Harvard Educational Review), and on-going improvements. The book was also written for a more general audience than just academia, though the coverage is thorough to satisfy a variety of readers.

My own introduction to the book was right at the time of teaching an undergraduate course in child development in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at Pennsylvania State University. I read the book when it came out. It had everything a student, interested reader, or policy maker would want. I immediately assigned it to the course and then another on child development programs and policies. Students really enjoyed reading and discussing the book. It provided many lessons for the field and programming. I highlight several of ZM's key foci of Head Start history and their relevance for current research and practice.

This history should be viewed within the larger context of the times, as the book makes clear. President Johnson introduced Head Start to the nation in a Reference Johnson1965 White House address as follows:

This means that nearly half the preschool children of poverty will get a head start on their future…Five and six year old children are inheritors of poverty's curse and not its creators. Unless we act these children will pass it on to the next generation, like a family birthmark. (May 18, paras. 6, 9)

This vision and goal were ambitious, long-term, and reflected the optimism that early childhood enrichment can ultimately improve economic well-being. The book recreates this context well.

The president's more positive vision of a “Great Society” appropriately places Head Start within a larger social and cultural purpose:

In our time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society. The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice. . . . But that is just the beginning. The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents . . . (cf. Silver & Silver, Reference Silver and Silver1991, pp. 83, 26)

“Project Rush-Rush”

Given the high priority and urgency of putting programs in place, Head Start was first implemented nationally as a summer program in 1965. The speed at which this occurred led the authors to label Head Start “Project Rush-Rush.” As ZM described,

everything was rushed—from the initial selection of program sites to the design of the first summer's program evaluation. In order to open the program by summer, Head Start's administrators had only six weeks to collect applications and another six weeks to process them . . . Moreover, this rapid implementation was taking place in a nation that, at the time, had very little experiences with early childhood programs. Kindergartens did not then even exist in 32 states. (p. 30)

During the times I used this book in courses, the students and I fully agreed with the perspective taken that an initial small-scale implementation was out of the question given the national need and climate of the times. This went against the textbook and a medical model approach to assess intensively and experimentally in pilot projects first, refine as needed to optimize impacts, and then slowly scale over time. Of course, unlike a new drug that may have unknown side effects, Head Start was providing health and dental care along with center-based enrichment to poor children, which were unmet needs. The risk of harm was extremely low, if any.

As ZM explained, however, the planning committee, which comprised mostly academics and researchers, wanted the program to begin with only a few thousand children. Sargent Shriver, the Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, thought otherwise, believing a nationwide program would be both more impactful and likely to be sustained. He and others observed early intervention projects, such as Susan Gray's Early Infancy Project in Nashville, and were impressed by their strong initial impacts. After the first summer, the Head Start was implemented year-round, and today remains one of the few programs of that era to continue to thrive. As ZM noted, for all of the difficulties that occurred in the early days, an initial nationwide implementation was the right call.

This raises the important issue of how to determine the pace of scaling in social and education programs. The priority and context of the times, social need, level of available evidence and promise, feasibility of implementation, and degree of innovation are all important criteria to consider. Although direct empirical evidence on impacts was lacking, all other criteria favored a large-scale implementation of Head Start. The downside of the “rush-rush” approach to Head Start was that it took decades of uneven quality and major changes to ensure the program was living up to the high expectations of benefits for children and families. There were calls over the years to scale back or even close the program when evaluations showed smaller effects than expected and evidence of “fade out” of achievement gains (ZM, Chapter 9).

Could more children have benefitted from a stronger program if it was implemented and scaled more slowly? Yes, that is possible. However, as the authors and Sargent Shriver noted, the smaller the footprint of the program, the more likely it would have been given lower priority, and not inspire the level of community support that did occur from the beginning. This was critical to its sustainability and resisting political pressure to scale back. It is also the case that very few pilot projects ever scale to populations levels, let alone nationally. An implication of the book is that implementing programs initially at large scale based on the criteria listed above could be a valuable alternative to the “go slow” incremental approach to prevention and intervention science that has been practiced for decades.

Comprehensive services

As the original federally developed and sponsored preschool program, ZM recount that Head Start was a revolutionary change in early childhood programming. Because of its social action mission in the Office of Economic Opportunity's War on Poverty, Head Start established a new definition of comprehensive services for early childhood programs. The four core components were (a) center-based educational enrichment for 4-year-olds, (b) family support services that included parenting classes, education, employment and job training, home visits, and participation in the center, (c) social services in the community such as mental health and housing supports, and (d) direct health services, including physical exams, dental care, and nutrition and meal services.

This is the definition of comprehensive services in early childhood for all programs today. Given the longstanding economic and social disenfranchisement of Black Americans, the focus was on children in poverty (Zigler & Syfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006; Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997). This has remained in place, though the family income threshold required to enroll has increased beyond the federal poverty line. Unfortunately, other than Head Start, few state prekindergarten and other publicly funded preschool programs currently provide comprehensive services consistent with this definition (Reynolds, Ou, Mondi, & Giovanelli, Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019). Long-run benefits and high economic returns as envisioned by President Johnson accrue to program that provide comprehensive services (Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple2008, Reference Reynolds and Temple2019).

Other than to match the vision toward a “Great Society,” the major reason for the comprehensive services model of Head Start was the composition of the planning committee. It was multidisciplinary in every respect, and covered individual to organizational and community levels.

To the best of my knowledge, the members of the planning committee have not been fully listed in a journal. They were as follows:

-

Dr. Robert Cooke, Chair, Pediatrics

-

Jule Sugarman, Executive Secretary

-

George Brain, Educational Administration

-

Urie Bronfenbrenner, Psychology

-

Mamie Clark, Psychology

-

Dr. E. Perry Crump, Pediatrics

-

Dr. Edward Davens, Pediatrics

-

Mitchell Ginsberg, Social Work

-

James Hymes, Jr., Early Education

-

Dr. Reginal Lourie, Child Psychiatry

-

Mary Kneedler, Nursing

-

John Niemeyer, Early Education

-

Dr. Myron Wegman, Public Health

-

Jacqueline Wexler, Religious Studies (Nun)

-

Edward Zigler, Psychology

Although not formally a committee member, Richard W. Boone was a key influence, and worked with Sargent Shriver as Director of Community Action Programs in the Office of Economic Opportunity. He also had previously worked as the Director of Special Projects on the President's Committee of Juvenile Delinquency and Youth Crime in 1963 with US Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

Local flexibility

As explained by ZM, the second key hallmark of the program was local flexibility in the design, implementation, and services provided to best suit the communities. Although federally funded with a local matching requirement, all resources went directly to the centers or agencies running the program (e.g., community organization, school district, faith-based entity) and not through state or regional intermediaries. Thus, the administrative structure (school vs. community-based), curriculum, length of day, and configuration of family services were locally determined. This is a highly underrated feature of Head Start as it established a self-governing philosophy of collaboration and direct ownership of decision making. This was core to the War on Poverty/Great Society vision of maximum feasible participation of the poor and all community members in service delivery.

Direct funding and resource allocations to communities without an intermediary authority encourage tailoring services to the needs of children and families. Such tailoring is a hallmark of effective social programs of all types. Greater autonomy and self-governance also helps to establish a learning culture that is based on a consensus-driven decision-making process (Comer, Reference Comer1980). Thus, members of the program and community at large share in governance functions, which increases self-efficacy and strengthens commitment to continuing improvement. Of course, conflicts may occur, and improvements in child and family outcomes are not guaranteed with a flexible service delivery and shared governance model.

Compared to the more traditional “top-down” hierarchical model of school districts, government agencies, and social institutions, however, stronger commitment to and engagement in the workings and aspirations of the program may result. Head Start has a long history of creating these types of organizational and service climates, but the alignment of these ideals with the operational systems of the school districts that most children enter after Head Start (and other preschools) requires much greater attention. This remains a challenge today to achieving an integrated continuum of learning over children's first decade.

Community action

This was the third hallmark of the program. As ZM described, the two-generation approach to economic opportunity was fundamental. This meant multilevel engagement not only in the center and at home, but participation in the community, civic engagement and volunteerism, and the utilization and tailoring of personal, health, employment, and mental health services for the entire family. Although the book and other key historical writings of Ed's came before the congressionally mandated national evaluation of Head Start's impact, the study design completely ignored these core philosophies of the program, especially local flexibility and multifaceted community action (e.g., Puma et al., Reference Puma, Bell, Cook, Heid, Broene, Jenkins and Downer2012). It instead focused on “average treatment effects” at the individual level. This contradicts key tenets of evaluating nonuniform program models (Rossi & Freeman, Reference Rossi and Freeman1995). For such programs and policies designed for local flexibility, preplanned analysis of variations in structure, leadership, and implementation is of critical importance.

An important part of Head Start history is the persistent tension between the community action and child development components of the program. In the social unrest of the times, community activists were largely dismissive of researchers, who they thought were motivated solely to enhance their professional reputation rather than create true social change. As an example, Ed reported that in the late 1960s:

I attended what I thought would be a routine academic conference chaired by my friend, the scholar Ed Gordon, who would become Head Start's first research director. The audience included both scholars and some pretty militant community people. While I was speaking, one of them interrupted with a tirade accusing me of using my research subjects to advance my own professional fame and fortune. I tried to explain the purpose of my work was to further understanding of the effects of poverty on children's development, and ultimately, to design better interventions. The man wouldn't hear it and continued his attack. (Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco2010, p. 62)

After Gordon defended the importance of Ed's research and others for the benefit of future generations, order was restored. This event and others described in the book and in ZM illustrate the tension between the community action and child development components of Head Start. They were both central to the program's vision and goals, but it took years of experience to satisfactorily balance the two, if they could ever be balanced in such a way to please everyone.

Narrow focus on cognitive gains

Given the comprehensive services mission, program goals were broad and went well beyond the traditional focus on cognitive development, mainly IQ test scores. Yet as ZM described in depth, IQ and achievement test scores were emphasized over other measures of well-being for two main reasons. First, as noted, and consistent with the environmentalist view of the Great Society era, it was widely believed that early childhood experiences could raise IQ scores by as much as 70 points (Bloom, Reference Bloom1964; Hunt, Reference Hunt1961). In addition, since it was presumed that increasing cognitive skills would lead to greater educational and then economic well-being, this viewpoint became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The second reason given for why cognition was the most common outcome measured is that cognitive tests were routinely used in research and had well-developed psychometric properties. Thus, they could be easily adopted for wide-scale assessment. In contrast, achievement motivation, socioemotional development, health, parent and family engagement, community participation and empowerment had no consensus measures. Although the focus on broader well-being is more present today, and IQ scores have given way to school readiness skills, comprehensive measurement of the full spectrum of outcomes remains rare. An important lesson of the book and in Dr. Zigler's writings is that impact assessment must tap all dimensions of child and family ecology.

As for comprehensive scholarly treatment of the theoretical, historical, research, and programmatic evolution of Head Start, Dr. Zigler's edited volume (Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1979; Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997 [2nd ed.]; Table 1) is the supreme source of information. One can dig deeper into the measurement of program goals and the overuse of IQ tests (Zigler & Trickett, Reference Ziger and Trickett1978), and broader social competence framework he articulated (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998; Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006). These are required reading for anyone interested in the measurement of outcomes in comprehensive programs. Although school readiness is the concept used today for short-term outcomes, and well-being for long-term outcomes, social competence is a major component of both.

B. Conceptualization and analysis of motivation as a core component of early childhood intervention impacts

As described in the planning committee report (US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1965) and elsewhere (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006; Zigler & Valentine, Reference Zigler and Valentine1997), the broad scope of Head Start as a poverty reduction program linked to seven major but unheralded goals (which are stated verbatim below):

1. improving children's physical health and physical abilities;

2. facilitating the emotional and social development of children by encouraging self- confidence, spontaneity, curiosity, and self-discipline;

3. training children's mental processes and skills with particular attention to conceptual and verbal abilities;

4. establishing patterns and expectations of success that foster confidence for future learning efforts;

5. expanding children's capacity to relate positively to family members and others while also strengthening the family's ability to relate positively to their children and their children's limitations;

6. developing in children and in families a responsible attitude toward society, and fostering constructive opportunities for society to work together with disadvantaged families in solving their problems;

7. increasing the sense of dignity and self-worth of children and families.

Although the goals were broad and consistent with the War on Poverty vision, it is remarkable that 4 of the 7 goals reflected psychological and socioemotional development, especially goals 2, 4, and 7. Naturally, Ed's perspective on the importance of motivation in adaptation and success was influential in the development of these goals (Zigler, Reference Zigler and Ellis1963; Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983; Zigler & Trickett, Reference Ziger and Trickett1978; Zigler & Turnure, Reference Zigler and Turnure1964). His work at the time showed the importance of motivation, expectations for success, and attitudes for positive adaptation.

The contribution of motivation to program effectiveness leads to the broader question of how to sustain gains. This is a frequent topic of conversation and research and policy in early childhood intervention. The traditional perspective was that intervention enhanced children's cognitive development, potentially at a large magnitude, and this carried forward throughout childhood and adolescence to greater well-being and achievement (Bloom, Reference Bloom1964; Hunt, Reference Hunt1961). This cognitive advantage brought about by the program was a major component of the “naïve” or “optimistic” environmentalism of the times (Zigler & Trickett, Reference Ziger and Trickett1978; Zigler, Reference Zigler1998).

Ed believed this view led to an overselling of the promise of early intervention and preschool education. In many conversations about this and related issues of strengthening gains, he offered alternative perspectives, including social competence as the framework to measure and understand the effects of intervention. Two elements of his social competence perspective were motivation and socioemotional adjustment. As Ed explained, “I believed then, as I do now, in the power of the environment to affect the motivation of any individual…to make the most of his or her life's chances.” (Zigler & Muenchow, Reference Zigler and Muenchow1992, p. 14)

In one of the original studies of the importance of motivation in early intervention (Zigler & Butterfield, Reference Zigler and Butterfield1968), it was shown that IQ test scores, or any individually administered cognitive assessment, have a motivational component and thus it is difficult, if not possible, to separate cognitive and socioemotional skills. For example, a 10-point change in IQ, which is two-thirds of a standard deviation, could be induced in 4-year-old Head Start children by changes in the testing conditions, place of testing, friendliness of the tester, wariness level of the child, item order, and time allocation (Seitz, Abelson, Levine, & Zigler, Reference Seitz, Abelson, Levine and Zigler1975; Zigler & Butterfield, Reference Zigler and Butterfield1968; Zigler, Abelson, & Seitz, Reference Zigler, Abelson and Seitz1973). These changes observed indicated that a large part of the improvements measured by tests were not actual changes in ability, but a combination of cognitive and motivational factors (Zigler et al., Reference Zigler, Abelson and Seitz1973). Thus, a broader set of outcomes to assess impacts and the key processes of change were needed.

Ed's conceptualization and analysis of motivation influenced my own perspective on sustaining gains, which led to the Five-Hypothesis Model of Intervention Effects (5HM; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2000). I display this model in Figure 1. The hypotheses are cognitive advantage, motivational advantage, socioemotional adjustment, family support behavior, and school and community support. The impact of intervention will depend on the characteristics of the program (e.g., timing, duration, intensity), characteristics of the family, child, and community – the conditions of risk. To the extent the intervention impacts the 5HM mediators, and the mediators’ lead to better outcomes, longer-term impacts will occur. These impacts of each mediator will of course vary by outcome. For example, education outcomes tend to be more directly affected by cognitive advantage, family support, and motivation, while social behavior (e.g., arrests) and mental health are affected by socioemotional adjustment and school quality (Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019; Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple1998; Schweinhart, Barnes & Weikart, Reference Schweinhart and Wallgren1993). Fewer studies of economic outcomes have been conducted, but several show improvements in economic well-being as a function of the five hypotheses, including motivation and socioemotional adjustment (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019).

Figure 1. Five-hypothesis model of intervention paths to adult well-being (links among mediators not shown). The model shows the contributing mediators to the transmission of early childhood programs to adult well-being. Motivational advantage and socio-emotional adjustment are most associated with Dr. Edward Zigler's contributions to the field and are noted. Outcomes of adolescence and young adulthood are not shown but would be similar. The magnitude of effects will vary by program attributes and child, family, and environmental context. Long-term direct effects of intervention are expected as a function of program participation positively influencing the five mediator constructs.

As shown, two of these hypotheses, motivational advantage and socioemotional adjustment, can be termed Zigler Hypotheses 1 and 2. Motivation (e.g., commitment, expectations), in particular was a key theme throughout Ed's writings and career in explaining how to sustain gains, or, alternatively, prevent drop-off in effects. The importance of motivation was central to the social competence goal of early childhood programs that Ed proposed, which included the components of physical health, formal cognitive skills, school achievement and performance, and socioemotional development, including motivation (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998, Reference Zigler, Meisels and Shonkoff1990; Zigler & Trickett, Reference Ziger and Trickett1978). They all related to meeting expectations within school, family, and social contexts.

Using 5HM as a context for better understanding how long-term effects are achieved, Ed and other scholars have described and prioritized for the field various processes of change. Conceptually similar to the “Matthew effect” in education (Walberg & Tsai, Reference Walberg and Tsai1983), which refers to the biblical verse describing how the rich get richer, three processes have been described to account for the long-term or sustained effects of early childhood intervention: (a) school success flow (Perry preschool; Schweinhart & Weikart, Reference Schweinhart and Weikart1980), (b) mutual reinforcement (Cornell Consortium), and the (c) snowball hypothesis (Zigler). They all involve motivation or school commitment directly or indirectly as follows.

In the transactional model, early education “provides disadvantaged children with a more favorable entry into the success flow of the school, increasing their commitment to the institution as well as their ability to meet its task-oriented demands. (Schweinhart & Weikart, Reference Schweinhart and Weikart1980, p. 66)

There begins a system of mutual reinforcement between the parent and child, the teacher and child, and the combination that ‘teaches’ that academic success is valuable. It is this continuing mutual reinforcement that could be responsible for the long-term effects . . . [It is a] “feedback” loop. (Lazar, Reference Lazar1983, p. 463)

The effects of successful experiences early in childhood snowballed to generate further success in school and other social contexts; the programs enhanced physical health and aspects of personality such as motivation and sociability, helping the child to adapt better to later social expectations; and family support, education, and involvement in intervention improved parents’ childrearing skills and thus altered the environment where children were raised. (Zigler, Taussig, & Black, Reference Zigler, Taussig and Black1992, p. 1002)

C. Development of preschool-to-third-grade programs and school reforms

In the past two decades, the definition of early childhood has expanded to include the entire first decade of life (0 to 9). This “first decade” perspective (Reynolds, Wang, & Walberg, Reference Reynolds, Wang and Walberg2003; Reynolds, Rolnick, Englund, & Temple, Reference Reynolds, Rolnick, Englund and Temple2010; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993) provides a unified approach for coordinating and integrating services. This has led to the preschool-to-third-grade (P-3) conceptualization for programming, which is in essence a school reform strategy to promote children's development continuity.

The rationale for P-3 is that it encourages alignment and integration of services during important early-life transitions. Enhancing these transitions synergizes their influence in improving later adjustment (Ramey & Ramey, Reference Ramey and Ramey1998; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds1994a; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019; Richmond, Reference Richmond, Zigler and Valentine1997; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993). To fully support the continuum of learning and developmental continuity, increases in program dosage, duration, and quality; teacher development; school and instructional quality; and family support are expected and essential (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019; Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple1998; Zigler & Seitz, Reference Zigler and Seitz1980; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993).

Historically, the conceptual basis of P-3 has been explicit, dating to the early 1960s and the Head Start planning committee. However, even to the present day, it has rarely been implemented successfully on a large scale. As Julius Richmond (Reference Richmond, Zigler and Valentine1997), the first Head Start Director, stated in the volume Project Head Start: The legacy of the War on Poverty:

It is clear that successful programs of this type must be comprehensive, involving activities generally associated with the fields of health, social services and education. Similarly, it is clear that the program must focus on the problems of child and parent and that these activities need to be carefully integrated with programs for the school years. (p. 122)

Dr. Zigler's impact on the development of P-3 as a school reform strategy for enhancing developmental continuity is greatly underrated. From his participation in the Head Start planning committee and perspectives on early childhood theories to contributions to the Follow Through program and ultimately to developing the School of the 21st Century model, Ed helped build the necessary foundation for creating systems of developmental continuity.

For example, adopting the P-3 approach avoids the all too common critical period trap – advocacy of one age period over another. As Zigler and Seitz (Reference Zigler and Seitz1980) explained, “the problem with critical periods is that there are too many of them. There are excellent arguments for the prenatal stage as a critical period, for the first few hours after birth, the first few months of life, the preschool years in general, the first few years of school, and so forth. A policy maker who takes the trouble to examine psychology's findings on critical periods might well end of hopelessly confused” (p. 363).

New Haven Head Start/Follow Through Project

One illustration of major contributions to P-3 and school reforms is Ed and Victoria Seitz's New Haven Follow Through Project as part of the Consortium for Longitudinal Studies. Among the 11 Consortium projects, this was the only one of a routinely implemented public program. Growing out of Head Start, Project Follow Through began in 1966 and was designed to promote continuity in learning in Head Start graduates’ transition to kindergarten and the early grades. Program elements included small classes, teacher professional development, enriched curriculum models, and family services.

Findings from the New Haven study of 140 low-income Black children born in 1962–1963 (Abelson, Zigler, & DeBlasi, Reference Abelson, Zigler and DeBlasi1974; Seitz, Apfel, Rosenbaum, & Zigler, Reference Seitz, Apfel, Rosenbaum and Zigler1983. see Table 1) indicated that Follow Through children (most of whom had Head Start) who completed the K-3 program made larger gains in achievement at the end of third grade and throughout most of the elementary than non-Follow Through children. Although the sample size was not large and there was significant attrition, findings supported the value of a comprehensive K-3 strategy for increasing achievement. Along with other studies (Conrad & Eash, Reference Conrad and Eash1983; Deutsch, Deutsch, Jordan, & Grallo, Reference Deutsch, Deutsch, Jordan and Grallo1983; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds1994a; Schweinhart & Wallgren, Reference Schweinhart and Wallgren1993), these results spurred the expansion P-3 programs and practices to the high priority that it is today (Manship, Farber, Smith, & Drummond, Reference Manship, Farber, Smith and Drummond2016; Reynolds, Magnuson, & Ou, Reference Reynolds, Magnuson and Ou2010; Takanishi, Reference Takanishi2016; Takanishi & Kauerz, Reference Takanishi and Kauerz2008).

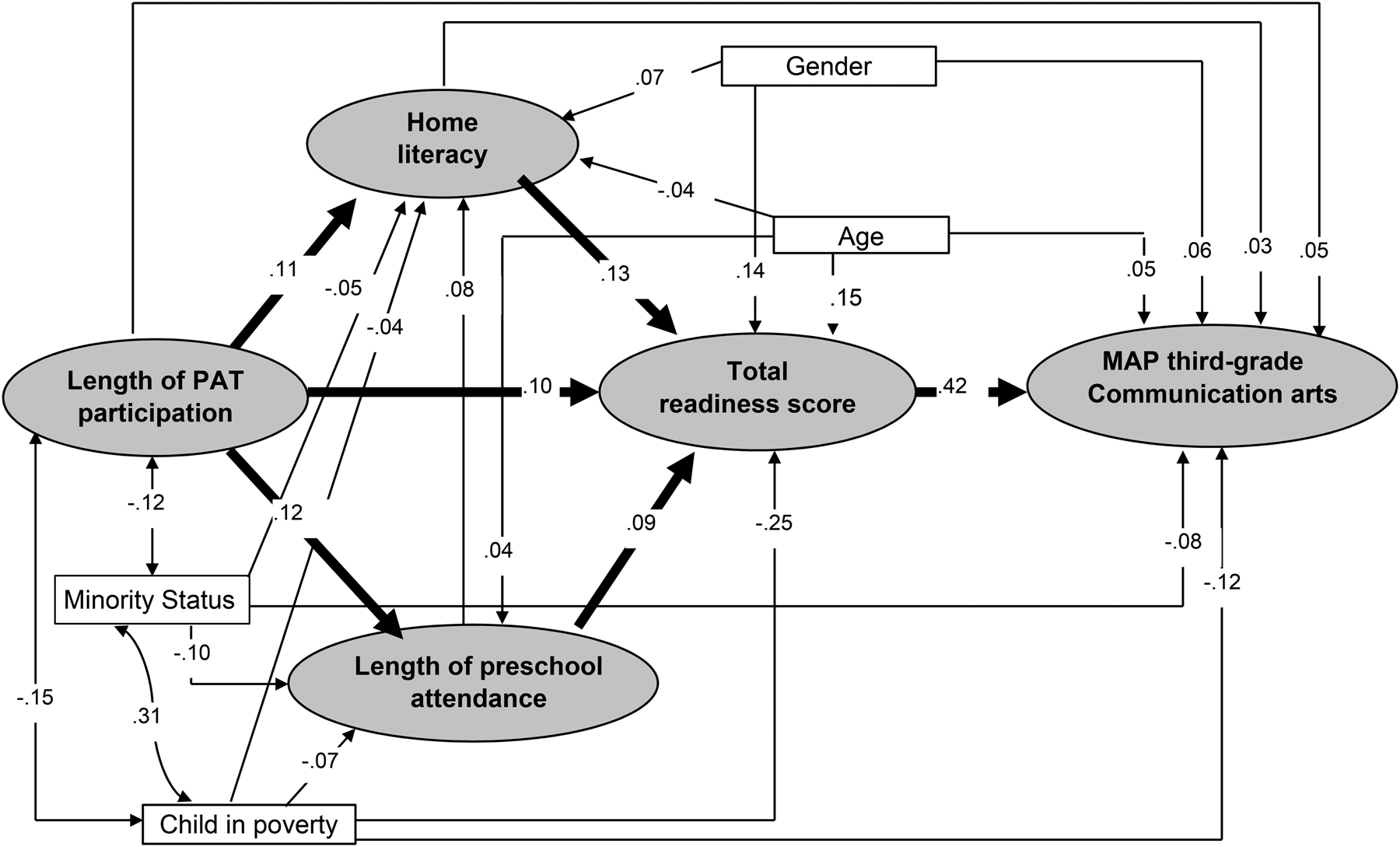

PAT and preschool program enrollment in Missouri

In a longitudinal study of the Parents as Teachers (PAT) home visiting program, Zigler, Pfannenstiel, and Seitz (Reference Zigler, Pfannenstiel and Seitz2008) assessed the dual impact of PAT for children in the first 3 years of life followed by preschool education. What is especially unique is that the sample of over 5,700 students was large and representative of all Missouri children entering public schools in 1998–2000. They were also followed through third grade. The results from the path analysis demonstrated a synergy between the two programs such that preschool strengthen outcomes above and beyond PAT and served as an important contributor to third-grade achievement. Parents’ reading to children (home literacy), a key impact of PAT, also directly predicted third-grade achievement. The direct and indirect effects of PAT on third-grade achievement suggest that this paraprofessional home visiting model can be an important part of a P-3 improvement strategy.

Figure 2 is a reprint of the findings of their main results. The standardized coefficients are from full-information maximum likelihood structural modeling. As shown the thick arrows, length of PAT participation, preschool enrollment, and home literacy contributed to a positive cycle of beneficial effects to third-grade achievement. Controlling for child and family background factors, school readiness skills strongly predicted later achievement. This suggests that early family support for children learning and early education can strong impact later success through improving school readiness skills.

Figure 2. Relations among Parents as Teachers (PAT), Preschool, Home Literacy and Early Achievement from Zigler et al. (Reference Zigler, Pfannenstiel and Seitz2008). Coefficients are standardized from path analysis. The darkened ovals show the primary relations among key program and outcome variables. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature, The Journal of Primary Prevention, Zigler et al. 2008, fig. 1, © 2008.

Although school-age intervention was not part of the study, the implications for enhancing developmental continuity during early childhood are clear. Given the positive evidence from his own work in Follow Through (Seitz et al., Reference Seitz, Apfel, Rosenbaum and Zigler1983) and in the larger field (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019; Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple2008; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993), this study provides further evidence and an analytic framework for assessing the synergies across programs as children grow up. Examining the entire first decade of life would be likely to reveal other important linkages, especially if the programs were aligned and in the same school contexts. The statewide composition of the sample in this study promotes generalization to other contexts and similar programs.

School of the 21st Century

As a further expansion of the developmental continuity system of P-3, Ed and Matia Finn-Stevenson developed the reform model, School of the 21st Century (Finn-Stevenson & Zigler, Reference Finn-Stevenson and Zigler1999). Compared to other school reform models, it is unique and provides prenatal through age 12 before- and after-school education, family support, and community-based services. Similar to Head Start, early childhood education and comprehensive services for parents and family members are major foci. This full-service reform model is designed to be adaptive to local needs and has been implemented in over 1,300 schools nationwide (Ginicola, Finn-Stevenson, & Zigler, Reference Ginicola, Finn-Stevenson and Zigler2013). This model contrasts with other school reform models and frameworks – excellent in their own right – such as James Comer's School Development Program (Comer, Reference Comer1980), and the 1970s and 1980s effective schools movement (Edmonds, Reference Edmonds1979, Reference Edmonds1982). The latter focused on leadership, high expectations for performance, and progress monitoring but ignored the early years of life and transition to school.

In conjunction with the School of the 21st Century, broader and more inclusive school reform models that support developmental continuity have been developed and implemented, including full-service schools (Dryfoos, Reference Dryfoos1990), the new American Primary School (Takanishi, Reference Takanishi2016), Child–Parent Center P-3 (Reynolds, Hayakawa, Candee, & Englund, Reference Reynolds, Hayakawa, Candee and Englund2016), and Community Schools (Institute for Educational Leadership, 2017). Linking early childhood development with school reform was unusual for a developmental psychologist, but it demonstrates the power of Ed's social action orientation.

The School of the 21 Century and a few other frameworks with key components are shown in Table 2, including James Comer's School Development Program, Ruby Takanishi's new American Primary School, and Lorraine Sullivan and Arthur Reynolds' CPC model. Although different in focus, they all espouse creating a nurturing learning environment for all children and families, teachers, leaders, and community partners.

Table 2. Key components of contemporary school reform models emphasizing early education

Note: See references for further information on each model (Finn-Stevenson & Zigler, Reference Finn-Stevenson and Zigler1999; Takanishi, Reference Takanishi2016; Comer, Reference Comer1980; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1971; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Hayakawa, Candee and Englund2016).

A social action scholar must prioritize scholarship and effort outside the university laboratory and into the larger contexts of society. These contexts should not only be the province of educators, educational psychologists, sociologists, and social workers. Faithful implementation of the ecological model requires such a social action orientation, and no one represented this better than Ed Zigler.

Aligning services federally

There is no better example of P-3 and beyond service integration and funding needs than Ed and Sally Styfco's book Head Start and beyond: A national plan for extended childhood intervention (Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993). In its relatively short length of 155 small-sized pages, the book covers all the essentials of a federal strategy for a coordinated model of funding to promote developmental continuity. As an added benefit, the chapter by the late Senator Ted Kennedy on the Head Start/Public School Transition Demonstration Project, which he shepherded through Congress, is historically insightful and valuable. The authors make a persuasive and ambitious case to combine and align four major programs for young children that existed at the time: Head Start, Follow Through, Head Start Transition, and Title I school aid from the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. The latter was by far the largest, as it had more than double the budget of Head Start (today it is even larger at $15 billion annually).

The following are some comments I made in a 1994 review of the book:

The Follow Through experience indicates that coordination between preschool and school-age programs and parent involvement components of the project will require special attention. Hopefully, [upward] expansion of Head Start can soon go beyond the demonstration stage . . . [In the last chapter] Zigler and Styfco compare Head Start, Follow Through, and Chapter I [Title I] along five criteria of successful intervention: provision of comprehensive services, parent involvement, innovation and dissemination, evaluation, and developmental continuity . . . They propose combining Chapter I, Follow Through, and the Head Start Transition Project into a new Chapter I Transition Project designed to provide extended childhood intervention services on a large scale. This volume makes a strong argument that such a plan is necessary to better coordinate early childhood programs and to best serve the needs of economically disadvantaged children. (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds1994b, p. 89)

Looking back and re-reading this grand vision of service coordination, I draw two conclusions. First, changes of this magnitude are very challenging even for the most optimistic of change agents. Both Follow Through and the Head Start Transition/Public School Transition Project no longer exist. Title I remains firmly entrenched in K-12 education with more of a focus on remediation rather than prevention.

The second conclusion is that the ideas and authors’ vision in the book live on. Many states and school districts have shifted to integrated models out of necessity, since most public prekindergarten programs are in schools. School principals as well as superintendents and state leaders have prioritized curriculum alignment and teacher collaboration across grades. Is there a unified national system of comprehensive supports on the order of what Head Start does for preschoolers or what is being accomplished in various school reform models? No, but progress is occurring. It is gradual, and it is based on the science-to-society social action model Ed long exemplified.

As Ed and Victoria Seitz (Zigler & Seitz, Reference Zigler and Seitz1980) concluded in their analysis of early childhood interventions:

our recommendation is that psychologists and policy makers commit themselves to the principle of the continuity of human development. We should now recognize the dangers of trying to provide societal supports at one stage only, as if that time were magically less expensive and would absolve us from the need to be concerned with other ages as well. The task is not to find the right age at which to intervene, but rather to find the right intervention for each age. (p. 363)

P-3 and school reform models reflect this important reality.

D. Critical analysis of theory, research, policy, and practice

Dr. Zigler had a keen eye for good scholarship and calling out poor ideas and suspect evidence. He was not afraid in the slightest of criticizing anyone regardless of the context or outlet. Mostly, he enjoyed it because he believed that scientific truth emerges from the critical analysis of ideas and data, and revealing both strengths and limitations. This was in the spirit of the tenet that validity emerges from the “sifting and winnowing” of evidence. It also is consistent with the belief of methodologist Donald Campbell, who Ed greatly admired, that scientific inquiry merits a “disputatious community of truth seekers” (Campbell, Reference Campbell, Conner, Altman and Jackson1984). Of course, Ed had high integrity for the value of theory, evidence, and practice. He was careful and rigorous in his thinking and writing, especially within a developmental frame but also for realism in social action to effectively scale routine practices. He also applied the same critical eye and rigor to his own ideas and work.

This critical analysis perspective as crucial for science and effective social policy is easy to miss or downplay in Ed's scholarship because for one, his work is so vast and multifaceted. Second, his involvement in child development programs and social policy has received the most attention, deflecting away from analyses. Moreover, some of Ed's best writings are books, book chapters, and commentaries in a variety of publications. Specialists, policy analysts, and child advocates would read these, but less so for the general scientific audience across the various social science fields.

Zigler & Styfco (Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006) chapter critiquing early interventions

To give a thorough perspective, I highlight his review with Sally Styfco (ZS hereafter, see Table 1) in the 2006 volume: The crisis in youth mental health: Early intervention programs and policies (Edited by Norman Watt and colleagues, Zigler & Styfco [Reference Zigler, Styfco, Watt, Ayoub, Bradley, Puma and LeBoeuf2006]). It is an exemplar of critical yet constructive analyses of research, programs, and policies. There are of course many other examples of this critical analysis of the field and trends in the discipline and society (Zigler et al., Reference Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006; Zigler & Berman, Reference Zigler and Berman1983; Zigler & Seitz, Reference Zigler and Seitz1980; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1993).

Going into the critique of the 13 chapters by renowned scholars in the field, ZS note the purpose of the book is to provide evidence and policy implications on the impact of early childhood programs. They provide constructive comments about the programs, research evidence, and implications for social policy in advancing child and family development. ZS explained their purpose as follows:

A huge literature makes very clear that high-quality early-childhood programs have stable of benefits…None of the studies contributing to this evidence was perfect, and critics of the very notion of preschool intervention have relentlessly point out their flaws. In this section, we will critique some of the evidence and views presented in this book, not to bolster the critics but to realistically assess the value of the studies’ contributions to the knowledge base and to the polices that base supports. (p. 356)

They began by covering the historical tension between basic and applied research in child development and in the broader discipline. As noted in the beginning of this article, Ed was early on critical of the prevailing zeitgeist that segregated basic and applied research but in fact the relationship is synergistic (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998). This tension remains today but larger social forces, including the coronavirus pandemic, are reducing the gap between the two.

ZS note that “our roots are in both child development and social policy, and we want to take issue with some of the common wisdom emanating from the early intervention literature because common wisdom can lead to bad social policy. Our ultimate goal is to provide scholarly debate that will inform effective policy and programmatic solutions” (p. 352).

Theoretical issues

It is argued by ZS that the intervention field, including many chapters in the book do not give sufficient consideration to genetic influences in development. The impact of focusing nearly exclusively on environmental influences in documenting effects is that investigators will not be sufficiently modest in claims. They further note that investigators commonly ignore the bioecological version of ecological systems theory. “Our major contention of current interpretations of the intervention literature is the pervasive underemphasis of the nature side of nature-nurture equation.” (p. 349) “Biology is also surprisingly absent in discussions of early brain development.” (p. 349).

Craig and Sharon Ramey/Abecedarian Project chapter

After acknowledging the landmark work of the Rameys in the development and long-term evaluations of the Abecedarian Project, Zigler and Styfco raise a number of questions about the research perspectives taken in the project. For one, they take issue with the cognitive focus and the dominance of IQ as an outcome measure in many early studies. Even though broader outcomes were included in later studies, they mention that “the Rameys may be the only major workers who continue to use IQ as a primary outcome measure, even emphasizing the intellectual and academic characteristics of the parents in explaining their findings.” (p. 357). They chastise the Rameys for referring to some critics of early interventions as “misguided and misinformed” since there will always be scholars or groups that disagree about the value or interpretation of evidence. This is the nature of the scientific process, though some critics are ideological advocates who do not follow the norms of science.

The authors also reinforce the need for modesty in interpreting effect sizes in this and other studies: “like other investigators, the Rameys extol the benefits accruing from participation in their program. Yet a caveat is in order. The findings of many early interventions are impressive when compared to the outcomes of other children who live in poverty. However, in absolute terms, intervention participants end up far from being paragons of society…for example, the Rameys control group had a 60 percent rate of grade retention, whereas the intervention group had half that rate.” (p. 358). The generalizability of findings from Abecedarian and Perry also are questioned, as the field needs more evidence for routine services at the population level.

David Olds/Nurse–Family Partnership chapter

ZS laud Olds and the Nurse–Family Partnership (NFP) for their unique and important work in providing a strong evidence base for home visiting through professional nurses as implementers. Through the original trial in Elmira, New York and replications in Denver and Memphis, NFP has, as noted, established itself as the most evidence-based model of home visitation for low-income, single mothers. However, ZS take issue with the rigidity by which they believe Olds interprets the evidence that nurses are superior and more effective than paraprofessionals in improving life-course outcomes. As ZS explain, “yet his interpretation of the Denver findings give the impression that we must choose between paraprofessionals and nurses. He concludes that the positive effects of the intervention are twice as large for the nurses, but this should not mean that paraprofessionals were useless or that a combination of the two could not promote desired outcomes, and be more cost-effective.” (p. 362). ZS offer PAT and Schools of the 21st Century as models that could be a better option for universal home visiting compared to the targeted approach of NFP. They conclude that “stumping for high quality is always good for public policy, but Olds may do a disservice to the field for overselling the weaknesses of other home-visiting programs” (p. 363).

James Heckman chapter on Human Capital

In an otherwise positive review of Heckman's chapter on the comparatively high returns early intervention program compared to job training and other economically oriented programs, ZS fault Heckman for ignoring neighborhood effects in the “Heckman curve” of the expected return of early childhood investment They also point out that the birth-to-age-9 focus of the chapter ignores prenatal development, which is of course foundational to learning outcomes. They also surmise that like research in general, cost–benefit results may change as new data and studies accumulate, and that it is important to examine the continuum of supports as children age rather than the impacts of a signal stage of development. This is also a major principle of the bioecological model and many life course theories. It is further notable that the “Heckman curve” is a theoretical summary and does not represent the empirical literature on economic returns that has accumulated over time (Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds, Temple, Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006, Reference Reynolds and Temple2008).

Larry Schweinhart/High Scope Perry Preschool chapter

ZS comment that this landmark study of early childhood intervention begun by David Weikart has had significant impact on public policy for demonstrating – in support of developmental theories of early enrichment – the long-term benefits of preschool on “real world” competencies. They comment that “High/Scope and a consortium of scientists (Consortium for Longitudinal Studies, 1983; Schweinhart et al., Reference Schweinhart, Barnes and Weikart1993) had the wisdom to look beyond IQ scores and found meaningful, lasting benefits in other developmental domains. For example, preschool graduates had less grade retention and special education placement. Justified in their efforts, interventionists were free to pursue their work of designing programs to impact desired outcomes beyond narrow and unattainable cognitive goals.” (p. 353).

ZS also explain, however, the limited generalizability of this and other model programs: “Most interventions are relatively small, local efforts. High/Scope and Abecedarian certainly were…each had a quite small number of participants. Both were internally evaluated, and neither were ever precisely replicated.” (p. 354). They go on to recommend expansion of and research on programs that have the feasibility of becoming routine practice.

Arthur Reynolds and Judy Temple/Child–Parent Center chapter

ZS laud the researchers and the Chicago CPC study for demonstrating not only positive long-term effects of a large-scale school district program, but also for the unique emphasis on mediators of effects. Two criticisms are offered. First, ZS disagree with the use of the family risk index as a control variable when it should have been used as a moderator: “The Chicago researchers treat level of risk as a variable to be controlled by statistical means. However, as we have learned from Early Head Start research as well as from the great amount of work done on risk and protective factors, magnitude of risk itself is a variable in determining for whom an intervention works and for whom it does not” (p. 357). They also argue that the ages-3-to-9 focus of the program is too narrow and ignores the birth to 3 period. In contrast, ZS note that the Schools of the 21st Century model is prenatal to age 12, and covers the full spectrum of services. This leads to the broader issue of the key importance of identifying the proper scope of services and the extent to which variations in effects by subgroups and other moderators should be prioritized.

Todd Risley/Betty Hart chapter on SES Differences in Early Vocabulary Skills

Concerning this well-known and intensive study of the relation between socioeconomic status (SES) and vocabulary development from the Juniper Gardens early intervention, ZS credit the investigators for helping the field move beyond the use of SES as an explanatory variable in performance to understanding variation within groups. Given a sample size of only 42 children across SES categories and the observational data analyzed, ZS note “Close observations of a phenomenon of interest can only be considered a starting point in scientific inquiry…In our opinion, the investigators subscribe much more value to their observational data than the inherent limitations permit.”

They also indicate that the investigators “ignore the undisputed fact that cognitive abilities, including those in the verbal area, have a strong genetic component. Even if Risley and Hart wish to ignore genetic influences, as Skinner did, there are many factors known to influence the IQ, such as motivation and physical and mental health” (pp. 364–365). Similar to some other chapters, ZS also criticize the study for ignoring genetic influences on IQ and other omitted variables in documenting this relationship. Although Hart and Risley are to be commended for documenting the importance of early reading to children and oral communication, it is noted that these are key components of Early Head Start and home visiting programs.

Critique of Zigler and Styfco's chapter

In the spirit of the high value Ed placed on critical analysis of ideas and evidence, I provide a critique of my own on the chapter, as he would encourage me or anyone to do. First, ZS uniquely bring to light many important issues about developmental concepts, research strategies, evidence, and program and policy prescription everyone in the field should read. They cover a wide scope of issues from theory and genetics to research design, findings, and policy implications. ZS are rightly critical and thorough in discussing the research of many of the most influential programs. This is the best part of the chapter. In the current era of even deeper specialization, such critical analysis of individual contributions is needed more than ever.

Early on ZS noted that while Bronfenbrenner's ecological model (now referred to as the bioecological model) has been of such great benefit to the field of human development, it is too general for program design and policy prescription. This is overly critical, however, given the breadth and systems perspective of the model. Not only does it address neighborhood and socio-cultural influences but has special value for conceptualizing how effects are sustained and the importance of examining processes of change. For example, the Five-Hypothesis Model (Figure 1; Reynolds & Ou, Reference Reynolds and Ou2011) was based largely on the framework, and has been valuable for promoting the expansion of early childhood programs, sustaining gains, and supporting developmental continuity (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Ou, Mondi and Giovanelli2019; Reynolds & Temple, Reference Reynolds and Temple2019 Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga, & White, Reference Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga and White2011a; Reynolds, Temple, White, Ou, & Robertson, Reference Reynolds, Temple, White, Ou and Robertson2011b).

ZS further explained that many chapters and the intervention field in general downplay genetic influences on development. However, given their purpose, the studies are not really downplaying genetics. They are highlighting the added value of enrichment environments after taking into account baseline characteristics, including entry cognitive skills. These would reflect, in part, innate influences. Moreover, measuring genetic influence is hardly meaningful in these studies, though full examination of subgroup effects would be illuminating in those projects having sufficient sample sizes. As ZS make clear, variation in impacts along a host of child and family factors certainly is increasingly important.