Historical and current representations of racial marginalization (e.g., racism, segregation, discrimination, and prejudice) disproportionally situate African American boys in social situations that are emblematic of the institutional and structural challenges that imperil positive development (Elsaesser & Voisin, Reference Elsaesser and Voisin2014; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Boyd, Cammack and Ialongo2012; Outland, Reference Outland2019). Inequitable access to scarce resources, concentrated poverty, and higher levels of crime, especially violent crimes, are characteristic outcomes of this structural and institutional racism (Foster & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Foster and Brooks-Gunn2009; Friedson & Sharkey, Reference Friedson and Sharkey2015). Youth who are constantly exposed to physical violence in their homes, schools, and communities are more likely to experience hyperarousal and thus more likely to copy violent behavior because of misreading innocuous situations as threatening (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; McMahon, et al Reference McMahon, Todd, Martinez, Coker, Sheu, Washburn and Shah2013; So et al., Reference So, Gaylord-Harden, Voisin and Scott2018; Phan et al., Reference Phan, So, Thomas and Gaylord-Harden2020). For urban youth, this is a grave issue as they are more likely than other counterparts to witness physical violence. In fact, throughout their lifetime more than 97% of urban youth witness (e.g., as a victim, perpetrator, or having heard about it) some form of violence (e.g., physical, verbal, sexual) whether at home, in school, or in their community (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Deatrick, Kassam-Adams and Richmond2011). This kind of violence exposure remains a major public health concern for African American youth in under-resourced communities (Sleet et al., Reference Sleet, Dahlberg, Basavaraju, Mercy, McGuire and Greenspan2011). African American adolescent boys in these situations may succumb to the negative influence of gangs and peer groups that reflect the disadvantages of the neighborhood, resulting in poor outcomes (Chen, Reference Chen2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Voisin and Jacobson2016; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Barker, Koot and Maughan2010; Voisin et al., Reference Voisin, Hotton and Neilands2014; Zimmerman & Messner, Reference Zimmerman and Messner2013). This study examines multiple factors that explain the long-term trajectory of the effect of witnessing physical violence on engagement in violent behavior for low-income African American boys.

Witnessed physical violence

Violence exposure is a chronic environmental stressor which impacts the emotional, social, and physiological development of African American boys in disadvantaged neighborhoods and includes observing or hearing about actual violence in their homes, schools, or neighborhoods (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Elsaesser & Voisin, Reference Elsaesser and Voisin2014). African American adolescents in urban contexts are at higher risk of personally encountering such community, physical or sexual violence, compared to their counterparts from other ethnic groups (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Voisin and Jacobson2016; Zimmerman & Messner, Reference Zimmerman and Messner2013) and males have disproportionally higher odds of exposure (Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Boyd, Cammack and Ialongo2012). Literature in this area suggests multiple mechanisms linking witnessing violence and negative cognitive and behavioral outcomes among African American adolescents in urban environments (Gaylord-Harden, Bai, et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Bai and Simic2017; Outland, Reference Outland2019). Moreover, rates of violent and aggressive behaviors among U.S. urban youth are between 50% and 100%, depending on the state (Buka et al., Reference Buka, Stichick, Birdthistle and Earls2010). African American boys in under resourced environments are more likely than any other race by gender group to witness physical violence (Gaylord-Harden, Bai, et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Bai and Simic2017; Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Barker, Koot and Maughan2010) and subsequent engagement in violent behaviors is a reflection of the premature environmental debut and autonomy experience by many African American boys in poor neighborhoods (Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Mars and Burns2012). Yet not all violence exposed youth go on to engaged in violent behaviors.

Witnessing violence has been associated with psychopathology evinced by both internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Lambert and Ialongo2013; Gaylord-Harden, Bai, et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Bai and Simic2017; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Deatrick, Kassam-Adams and Richmond2011). Considerable literature has demonstrated the connection between witnessing violence and poor mental health outcomes like depression (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Epstein, Nurius, Gorman-Smith and Henry2019), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Bennett, Reference Bennett2019), and maladaptive cognitive coping behaviors such as avoidance (Stoddard et al., Reference Stoddard, Heinze, Choe and Zimmerman2015) for this population.

Interpersonally, witnessing acts of physical violence has been linked to increases in aggression in peer relationships (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, Reference Gorman-Smith and Tolan1998; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Todd, Martinez, Coker, Sheu, Washburn and Shah2013), and poor social adjustment during adolescence (Carey & Richards, Reference Carey and Richards2014). Additionally, research suggests strong positive links between violence exposure and perpetuation of violent acts (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Paxton and Jonen2011). Thus, witnessing violence compromises positive development and increases the likelihood of violent behaviors.

Self-efficacy to avoid violence

Self-efficacy to avoid violence is a mechanism that can explain how witnessing leads to violence. Faced with major risks to their safety and positive development, African American boys and their families, especially those in poorer neighborhoods, must develop and sustain behaviors and cognitions that moderate the impact of negative experiences like witnessing violence. Reflective of the risk element of the risk and resilience framework (Fergus & Zimmerman, Reference Fergus and Zimmerman2005) we propose that adolescents’ belief in their ability to make positive decisions (Bennett & Fraser, Reference Bennett and Fraser2000) and their expectations for safely navigating opportunities for engaging in violent behaviors (self-efficacy to avoid violence) is undermined by witnessing physical violence. This weakening of adolescents’ violence avoidance efficacy helps us understand how witnessing physical violence is related to violent behavior overtime (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Farrington & Ttofi, Reference Farrington and Ttofi2011; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Todd, Martinez, Coker, Sheu, Washburn and Shah2013).

Risk and resilience frameworks simultaneously consider the role of risk as well as resilience factors. The concept of resilience, defined as the ability to overcome adverse conditions and to function normatively in the face of risk, helps public health programs and interventions focus on modifiable factors as key elements of curriculums that can protect youth and help them develop resilience, in the face of adversity (Jenson & Fraser, Reference Jenson and Fraser2006). Apart from having direct links to increased likelihood of violent behaviors (Calvete & Orue, Reference Calvete and Orue2011; Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011), violence exposure also has indirect associations to violent behavior through a weakening of adolescents’ future self-efficacy to avoid violence (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Huesmann et al., Reference Huesmann, Boxer, Dubow and Smith2019). The undermining of self-efficacy to avoid violence leaves adolescents unprotected in high-risk environments, particularly when parents and other adults are not immediately available to protect and intervene. In the current study we examine how witnessing violence undermines youth’s efficacy to avoid violence overtime. However, protective factors like parent monitoring, and violence avoidance communication can keep youth safe by reducing access to risky situations (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Voisin and Jacobson2016; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; Pasko & Chesney-Lind, Reference Pasko and Chesney-Lind2012), conveying anti-violence values (Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Paxton and Jonen2011), and building and enhancing adolescents’ efficacy to avoid violence (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a). Moreover, parents’ violence avoidance communication and monitoring have the unique benefit of being able to provide some protection to adolescents by enhancing efficacy to avoid violence and reducing the impact of environmental risks when parents cannot be physically present.

Parenting influence on violence exposure

Parenting practices can serve as both a structural barrier preventing violence exposure, and a socioemotional factor that attenuates the negative effects of risk exposure on adolescent development or functioning (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Hammack et al., Reference Hammack, Richards, Luo, Edlynn and Roy2004; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018). Parenting practices are widely recognized as a major influence on adolescent development and decision making and vary based on parenting styles. The authoritative parenting style, for instance is generally associated with greater monitoring and higher levels of warmth, qualities that are known to have better child outcomes, when compared with authoritarian, indulgent and neglectful approaches (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Coates and Smith-Bynum2019). For this study though we focus not on the larger construct of parenting styles but on two specific characteristics of supportive parenting – communication and monitoring.

Poor parental monitoring, for example, is associated with negative adolescent behaviors especially in poorer neighborhoods (Jolliffe et al., Reference Jolliffe, Farrington, Piquero, Loeber and Hill2017; LeBlanc et al., Reference LeBlanc, Self-Brown, Shepard and Kelley2011). Moreover, research in this area has found decreases in risky behaviors for African American adolescents who received positive parent communication and monitoring (Neppl et al., Reference Neppl, Dhalewadikar and Lohman2016). Highlighting specific parental practices, studies have also shown that communication about specific risk behaviors has been related to better outcomes (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Gorman-Smith et al., Reference Gorman-Smith, Henry and Tolan2004; LeBlanc et al., Reference LeBlanc, Self-Brown, Shepard and Kelley2011). Parents’ communication of non-supportive views of violence to adolescents is associated with fewer aggressive behaviors even when adolescents’ own attitudes toward violence are taken into consideration (Copeland-Linder et al., Reference Copeland-Linder, Jones, Haynie, Simons-Morton, Wright and Cheng2007; Kliewer et al., Reference Kliewer, Parrish, Taylor, Jackson, Walker and Shivy2006; Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011). Adolescents who received more messages from their parents, that discouraged violence as a means of problem solving were less likely to engage in aggressive behaviors. Researchers suggest too, that other factors like existing behavior problems and neighborhood effects contribute to adolescent outcomes and may overshadow overt parental influences like monitoring and involvement, especially where serious delinquency is concerned (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Krueger, Johnson, McGue and Iacono2009; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Deatrick, Kassam-Adams and Richmond2011).

The critical role of parents’ communication about risk is highlighted in that adolescents’ beliefs that their parents did not support violence are more predictive of youth violence than family structure, the parent-child relationship, or parental monitoring (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Orpinas et al., Reference Orpinas, Murray and Kelder1999). Parents’ beliefs about violence, whether communicated directly to adolescents or perceived, shape adolescents’ own views about violence. These messages also strengthened youth’s efficacy for avoiding violence. In a study of 5581 adolescents Farrell et al. (Reference Farrell, Henry, Mays and Schoeny2011) found that, especially for African American boys in poor urban settings, parents’ nonviolence messages or communicated non-supportive values about violence reduced violent behavior and deviant peer affiliation. The protective effect of these messages conveyed by parents dissipated by the end of sixth grade.

Researchers have suggested differences in cognitive and behavioral outcomes for African American adolescent boys based on the type of parenting style experienced. For instance, parental socialization of African American boys that features less monitoring and involvement and early environmental debut (Fagan et al., Reference Fagan, Van Horn, Hawkins and Arthur2007; Perrone & Chesney-Lind, Reference Perrone and Chesney-Lind1997), characteristic of indulgent and neglectful parenting styles, is linked to more physical violence exposure, and related negative outcomes (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Jagers and Flay2016b; Fagan et al, Reference Fagan, Van Horn, Hawkins and Arthur2007). However, engaged parenting and expressed expectations of nonviolence have been linked to fewer externalized behaviors in young African American adolescent boys (Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a), particularly those living in low resourced contexts.

Theory

Recognizing the critical role of parents as important first and long-lasting socialization agents (Theiss, Reference Theiss2018), and in keeping with our focus on strengths and resilience we couch the study in a risk and resilience framework and through an ecological lens. The risk and resilience framework identifies the promotive and protective roles of assets (internal to the individual) and resources (external to the individual) in the context of risk (Fergus & Zimmerman, Reference Fergus and Zimmerman2005). The major risks in this study are witnessing physical violence, a traumatic experience more common to disadvantaged neighborhoods, and low efficacy to avoid violence. Neighborhoods marked by high rates of poverty offer fewer educational, social, and physical resources (e.g., lower quality schools, fewer youth-serving agencies such as boys and girls clubs) and fewer opportunities to learn new skills or interact with positive adult role models as socialization agents compared to more affluent areas (Elsaesser & Voisin, Reference Elsaesser and Voisin2014; Friedson & Sharkey, Reference Friedson and Sharkey2015; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Boyd, Cammack and Ialongo2012; Outland, Reference Outland2019). Parenting efforts at protecting youth in under resourced neighborhoods benefit from the influence of neighborhood efficacy – the perception that neighbors share similar values and are looking out for each other (Authors). Poorer communities often have higher rates of unemployment and single-parent families, which further reduce children’s contact with adults who are positively bonded to social institutions and who can provide consistent supervision and monitoring (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Jagers and Flay2016b; Chung & Steinberg, Reference Chung and Steinberg2006). This makes parents critical in protecting adolescents by reducing exposure, or by nurturing values and practices as prophylactic measures for adolescents’ navigation of challenging environments. By socializing their youth for responding to existing risks parents enhance resilience qualities and skills that can be acquired in the context of risk (Buzzanell, Reference Buzzanell2010).

From an ecological lens, adolescent outcomes are a product of interactions between the environment, the adolescent, and the socialization agents with whom youth engage. Interestingly, literature indicates that when applying this model to African American youth in poor urban communities, results depended on parental influence and relationship quality (Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016; Moore & Chase-Lansdale, Reference Moore and Chase-Lansdale2001). As part of their effort to insulate their children from the effects of risk, parents engage in two dimensions that often underlay parental communication: responsiveness and control. According to Baumrind’s (Reference Baumrind1991) dimensions of parental communication, the first dimension, parental responsiveness, attempts to shape children’s emotional and behavioral response to interpersonal interactions, while the second dimension, control, attempts to restrict children’s emotions and actions. The risk and resilience model (Fergus & Zimmerman, Reference Fergus and Zimmerman2005) offers an additional approach to understanding the impact of parental influence, in this case parental responsiveness, on African American youths’ behavior. The model purports that through specific responsive behaviors parents serve protective and promotive roles for youth in the context of elevated risk. These responsive parenting behaviors are resources that adolescents can draw upon as they interact with risks in their environment. Such resources buttress and promote the development of adolescents’ assets.

Current study

Despite the challenges associated with disadvantaged communities, not all residents commit or support illegal behaviors, and not all youth from these areas become delinquent or violent. In fact, existing research has shown how specific parenting efforts and messages predict better outcomes for African American adolescents (Neblett et al., Reference Neblett, Rivas-Drake and Umaña-Taylor2012). We use data from an intervention that examined the effects of three conditions (social development curriculum, school/family/community intervention, health enhancement control) on violence, unsafe sex practices, and substance use among low-income African American children. The current study controls for the effect of the intervention, and instead focuses on an examination of the long-term link between witnessing physical violence and violent behavior, and the protection that parents may provide among this sample of African American low-income adolescent boys.

We highlight the long-term negative trajectory of witnessing physical violence via its direct effect on violent behavior overtime. We test a first stage dual moderated mediation model that assesses whether the indirect effect of the predictor on the outcome through the mediator is influenced by a moderator variable, but the moderation effect is from the predictor to the mediator. In other words, efficacy to avoid violence will mediate the association between witnessing violence and violent behavior. Specifically, higher levels of witnessing lead to less efficacy to avoid violence, which in turn leads to more violent behavior. We also test a moderation effect on the direct relationship between the predictor and main outcome variable. As youth witness more violence, they may feel that they cannot avoid engagement in violence and end up engaging in it after all. Violence avoidance communication and monitoring will moderate the relationship between witnessing and efficacy to avoid violence. We control for the effect of the intervention in these analyses. The following hypotheses guide this study:

-

1. Efficacy to avoid violence (T2) will mediate the relationship between witnessing violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2) such that the association between witnessing violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2) will be explained by efficacy to avoid violence (T2).

-

2. More experiences of witnessing violence (T1) will be linked to lower efficacy to avoid violence (T2), and more violent behaviors (T2). Parenting practices will moderate the relationship between witnessing violence and efficacy to avoid violence and moderate the direct effect of witnessing violence on violent behavior. Specifically for the violence avoidance communication variable:

-

a. Parents’ violence avoidance communication (T1) will moderate the relationship between predictor (witnessing violence T1) and mediator (efficacy to avoid violence T2) such that higher levels of violence avoidance communication (T1) will be related to greater efficacy to avoid violence (T2), when witnessing violence (T1) is high and this association will be related to fewer violent behavior (T2).

-

b. Parents’ violence avoidance communication (T1) will moderate the link between witnessing violence (T1) and violent behaviors (T2) such that more violence avoidance communication (T1) will be associated with fewer violent behaviors (T2) when witnessing violence (T1) is high.

-

-

3. Regarding parental monitoring we expect that:

-

a. Parental monitoring (T1) will moderate the relationship between the predictor (witnessing violence T1) and the mediator (efficacy to avoid violence T2) such that higher levels of monitoring (T1) will be related to more efficacy to avoid violence (T2) when witnessing violence (T1) is high, and this link will be associated with fewer violent behaviors (T2).

-

b. Parental monitoring (T1) will also moderate the link between witnessing violence (T1) and violent behaviors (T2) such that greater monitoring (T1) will be associated with fewer violent behaviors (T2) when witnessing violence (T1) is high.

-

Method

Design and setting

The current study employs a longitudinal design using data from the ABAN AYA Youth Project (AAYP), a community study of African American school age youth. The current study received IRB approval from the University of Michigan and met all the ethical standards of research involving ethnically marginalized (vulnerable) youth.

Data collection

The AAYP was conducted in poor metropolitan neighborhoods of Chicago, among 12 schools during the 1994–1998 academic years. We gathered self-report data at the beginning of fifth grade (pretest, n = 668), and post-tests at the end of grades five (n = 634), six (n = 674), seven (n = 597), and eight (n = 645) for a total of 1153 African American students, of whom 339 were present at all 5 times (Liu et al., Reference Liu and Flay2009). We consented participants from K-8 schools with, enrollments of 500+ African American students, more than 80% African American students, and less than 10% Latino/Hispanic students. Excluded schools were on probation or slated for reorganization; or were a special or a designated school (e.g., moderate mobility, magnet, academic center). Schools which met the inclusion criteria (N = 155; 141 inner city and 14 suburban) were stratified into four quartiles of risk based on a score that combined proxy risk variables using procedures described by Graham et al (Reference Graham, Flay, Johnson, Hansen and Collins1984). Less than 1% of students contacted denied consent in grades 5–7, and 1.7% did so in eighth grade. We gathered baseline data from students who were the original 1994–1995 cohort, whereas the remainder of the students transferred into the participating schools. Those who transferred out of the school were not followed, but their data were retained for analysis. An analysis of differences between the original cohort and subsequent cohorts on violence at each students’ pre-intervention assessment (controlling for pre-intervention age and modeling school-level nesting), revealed no differences, b = 0.185(0.126), t = 1.47, p = 0.141. Thus, the original cohort and transfer students were included in the same analysis (see Jagers et al., Reference Jagers, Morgan-Lopez and Flay2009). The mean age of participants was 10.2 years at the beginning of fifth grade and 14.3 years at the end of eighth grade. About half of the sample was male (49.5%), and approximately 77% were eligible for free and reduced lunch programs. Average household income at baseline was $10,000–$13,000. Forty-seven percent of participating students lived in two-parent households.

Participants

In the current study we used data only from African American boys (N = 310) who had data at Time 1 or fifth grade and Time 2 or seventh grade. Using these two time points allowed us to keep the longitudinal perspective with the largest number of Black male adolescents for the questions at the core of the present study. Boys were, on average, 10.2 (SD = 0.62) years old at Time 1 and 13.5 (SD = 0.62) years old at Time 2. They had lived on average, 3.6 years (SD = 1.36) in their neighborhood with a maximum of 7 years. Nearly half (47%) lived in two-parent families and household income averaged $10,000 with 14% on incomes of more than $40,000. Most parents had completed high school or a 2-year college degree (80%), and more than 20% had some college-level course work, a 4-year college degree, or a post college–level degree.

Measures

The study variables included baseline child’s age, parental education, intervention, Time 1 witnessing violence and violent behaviors; and at Time 2, parental violence avoidance communication, parental monitoring, violence avoidance self-efficacy, and violent behavior. All measures in this study are based on adaptations of previously applied questionnaires including but not limited to the 1992 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (YRBSS; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993) (see Jagers et al., Reference Jagers, Morgan-Lopez and Flay2009). The AAYP adapted the measures based on focus groups’ feedback and pilot testing with a lower number of adolescents and parents living in similar high-risk communities (see Flay et al., Reference Flay, Graumlich, Segawa, Burns and Holliday2004).

Witnessed physical violence

Adolescents reported lifetime frequency of witnessing physical violence using five items: “Have you ever seen:” 1) a physical fight where someone was badly hurt, 2) someone get cut/stabbed, 3) someone get shot at, 4) a friend or family member get cut, 5) a friend or family member get shot. Items were on a dichotomous scale (0 = no, 1 = yes). We calculated a sum score ranging from 0 to 5 where higher scores were indicative of witnessing more physical violence over their lifetime. This measure was also internally consistent T1 (α = 0.68) and T2 (a = 0.71).

Violence avoidance self-efficacy

We used four items to assess violence avoidance self-efficacy. Participants were asked “How sure are you that you can” 1) keep yourself from getting into physical fights, 2) keep yourself from carrying a knife, 3) stay away from situations in which you could get into fights, and 4) seek help instead of fighting. Response options were 0 = definitely cannot, 1 = maybe cannot, 2 = not sure, 3 = maybe can, and 4 = definitely can. We computed a total score ranging from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating more perceived ability and self-efficacy to avoid violent acts. The measure was internally consistent T1 (α = 0.83) and T2 (a = 0.87).

Parents’ violence avoidance communication

Parents reported the frequency with which they talked with their sons about avoiding violent behaviors. The following 2 items were used. “You talked to your son about” 1) physical fighting, and 2) carrying a gun or weapon. All items were on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, where 0 = no conversation and 3 = frequent conversation. The total parental communication score ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more frequent parent communication about avoiding violence. The items were correlated at Pearson’s coefficient (T1) r = 0.54, and (T2) r = 0.73 (p < 0.01), and a Spearman Brown coefficient of (T1) r = 0.53, and (T2) r = 0.73 (p < 0.01). The literature has suggested additional reporting of the Spearman Brown coefficient when exploring the reliability of two-item scales (Eisinga et al., Reference Eisinga, Te Grotenhuis and Pelzer2013).

Parents’ monitoring

Parents reported the frequency with which they monitored their sons’ activities using the items: “How often do you:” 1) Talk with your child about how they are doing in school, and 2) Talk with your child about how they are going in their life. Items were on Likert scale, 0 = no conversation and 3 = frequent conversation. We calculated a total parental monitoring score ranging from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating frequent monitoring. The items were correlated at (T1) r = 0.35, and (T2) r = 0.45 (p < 0.01), and a Spearman Brown coefficient of (T1) r = 0.27, and (T2) r = 0.34 (p < 0.01).

Violent behaviors

Using seven items adapted from the 1992 National Health Interview Survey-Youth Risk Behavior Survey (NHIS-YRBS; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1993) adolescents reported frequency of engagement in various violent behaviors (Kann et al., Reference Kann, Kinchen, Williams, Ross, Lowry and Grunbaum2000). Given that the YRBSS was designed for high school students, we needed to modify the questions to cover a range of common and more serious types of violence that can be seen across levels of violence. The items asked the lifetime engagement in the following acts: 1) threatened to beat up someone; 2) been in a physical fight; 3) threatened to cut, stab, or shoot someone; 4) carried knife or razor; 5) carried a gun; 6) cut or stabbed someone, and 7) shot at someone. Responses were either 0 = no or 1 = yes, which indicated absence or presence of lifetime monitoring of the participant in these acts. We calculated a sum score ranging from 0 to 7. Higher scores indicated more violent behaviors. Our outcome had an Cronbach alpha of T1 (α = 0.60) and T2 (α = 0.69) in this sample.

Intervention

Interventions were provided at school – rather than student level. Participating schools were randomized to the following three conditions: (1) the Social Development Curriculum, (2) the School and Community intervention (family and neighborhood Interventions), and (3) the Health Enhancement Control condition. As the two intervention curriculums had similar prevention effects compared to the Health Enhancement Control (Flay et al., Reference Flay, Graumlich, Segawa, Burns and Holliday2004), we treated the intervention group as a dummy variable: 1 = any of the two intervention conditions, and the 0 = control group (Ngwe et al., Reference Ngwe, Liu, Flay and Segawa2004).

Demographics

Boys’ age was a continuous variable, and parent education was reported on an 11-point scale from 1 = 8th grade or less to 11 = Post-college or Professional degree.

Statistical Analyses

We performed analyses using IBM SPSS software version 27. We tested our hypotheses, using Mediation (Model 4) and moderated mediation (Model 8) in the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). Age, gender, mother’s education as a proxy for socioeconomic status, violent behavior (T1), and intervention group were included as covariates in each model. The indirect effects with bias corrected bootstrapping (n = 5000) and confidence intervals (CI) for indices were employed. Parameter estimates are significant if bootstrapped CI at 95% do not include zero.

Results

Descriptive statistics

We calculated means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations (r) for all variables in this study (Appendix A). Most boys in this sample (84%) reported witnessing a physical fight where someone was badly injured, almost half had witnessed very serious violent acts including seeing someone cut, stabbed or shot at, and 70% report the victims of these acts of violence were family members and friends, resulting in a potentially more traumatic experience. Of the 310 African American adolescent boys in this study 91.9% had witnessed at least one potentially traumatic act of violence, 44.5% had witnessed 3 or more such acts (Appendix A). Physical fighting was the most common behavior with 96% reporting engagement in this behavior. About 80% of the sample reported having threatened to beat up someone. Few had been involved in more serious behaviors like physical fights that lead to injury (15%). A smaller subsample (12%) had threatened to cut or stab someone or engaged in acts like carrying a gun (12%), cutting/stabbing someone (7%), or shooting at someone (5%). Participants reported elevated efficacy to avoid violence, violence avoidance communication and monitoring (resources). Almost 70% reported mean levels of efficacy to avoid violence with an additional 12.7% reporting efficacy levels at least 1 standard deviation above the mean of 11.17 with a maximum possible score of 16. Most of the African American boys, 87.5%, reported more than the average (4.47) amount of parental violence avoidance communication, while 67.3% experienced monitoring that was at least average for this sample (Appendix A).

Bivariate analyses

Witnessing physical violence (T1) was positively correlated with violent behavior T1 (r = 0.469, p < 0.01) and T2 (r = 0.371, p < 0.01) respectively, but negatively correlated with (T2) efficacy to avoid violence (r = −0.129, p < 0.01). Violent behavior at (T1) was positively linked to (T2) violent behavior (r = 0.418, p < 0.01), and negatively related to (T2) efficacy to avoid violence (r = −0.155, p < 0.001) and (T2) parental monitoring (r = −0.222, p < 0.01). Efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was positively linked to (T2) violence avoidance communication (see Appendix B).

Mediation effect of efficacy to avoid violence

We tested hypothesis 1, controlling for the effects of age, mother’s education, and intervention group (Appendix C). The effect of witnessing physical violence (T1) on violent behavior at (T2) was significant (B = 0.339, SE = 0.047, p < 0.001) suggesting that boys in this sample who witnessed more physical violence (T1) were more engaged in violence at Time 2. Witnessing violence (T1) was also linked to (T2) efficacy to avoid violence (B = −0.247, SE = 0.121, p < 0.042), indicating that boys who had witnessed more violence reported less efficacy to avoid violence. The standardized indirect effect of witnessing violence (T1) on violent behavior (T2) through efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was significant, B = .030, SE = .016, 95% CI = [.001, .064]. Efficacy to avoid violence (T2) had a mediating effect on the link between witnessing violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2), confirming hypothesis 1.

Moderated mediation effects

Hypotheses 2 and 3 were tested independently by estimating a moderated mediation model (Model 8) for (a) violence avoidance communication and another for (b) parental monitoring using PROCESS macro (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013) with the control variables. The moderated mediation model is shown in Figure 1 where X was the independent variable (witnessed violence T1); Y was the dependent variable (violent behavior T2), M was the mediator (efficacy to avoid violence T2), and W were the independent moderators (a) (violence avoidance communication T2) and (b) (parental monitoring T2).

Figure 1. The moderated mediation model controlling for age, parent education, intervention, violent behavior (T1) (all coefficients are standardized). NB: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001. (a): violence avoidance communication as moderator and (b): parental monitoring as moderator, each moderator included in a model independent of each other.

Moderating effect of communication on the links between witnessing violence, efficacy and violent behaviors

The test of hypotheses 2a and 2b revealed significant effects of the model predicting associations between witnessed violence (T1) on (T2) efficacy to avoid violence (R2 = 0.232, F(9, 300) = 10.077, p = 0.000) and on (T2) violent behavior (R2 = 0.376, F(10, 299) = 18.016, p = 0.000) respectively (Table 1). Violence avoidance communication moderated the associations between witnessed violence and efficacy to avoid violence [b = 0.294, SE = 0.086, 95% CI = (0.124, 0.463)]. Violence avoidance communication also moderated the association between witnessed violence and violent behavior [b = 0.106, SE = 0.035, 95% CI = (0.038, 0.175)].

Table 1. Testing the moderated mediation effects of parental communication about violence (N = 310)

NB: W = Witnessed violence; C = Violence Avoidance Communication; Efficacy: Violence Avoidance Efficacy; Violence: Violent Behavior. (a): model predicting violence avoidance efficacy. (b): model predicting violent behavior.

We conducted simple slopes tests to interpret these two moderation relationships. For hypothesis 2a the tests show that at low (−1SD) [βsimple = −0.631, SE = 0.175, p < 0.001] and average levels [βsimple = −0.243, SE = 0.126, p = 0.054] of violence avoidance communication (T1) the effect on the association between witnessed violence (T1) and efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was negative and significant. However, at high levels of violence avoidance communication (+1SD) [βsimple = 0.144, SE = 0.165, p = 0.384] the effect was not significant (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conditional effects of violence avoidance communication (T2) on the link between witnessed violence (T1) and violent avoidance efficacy (T2).

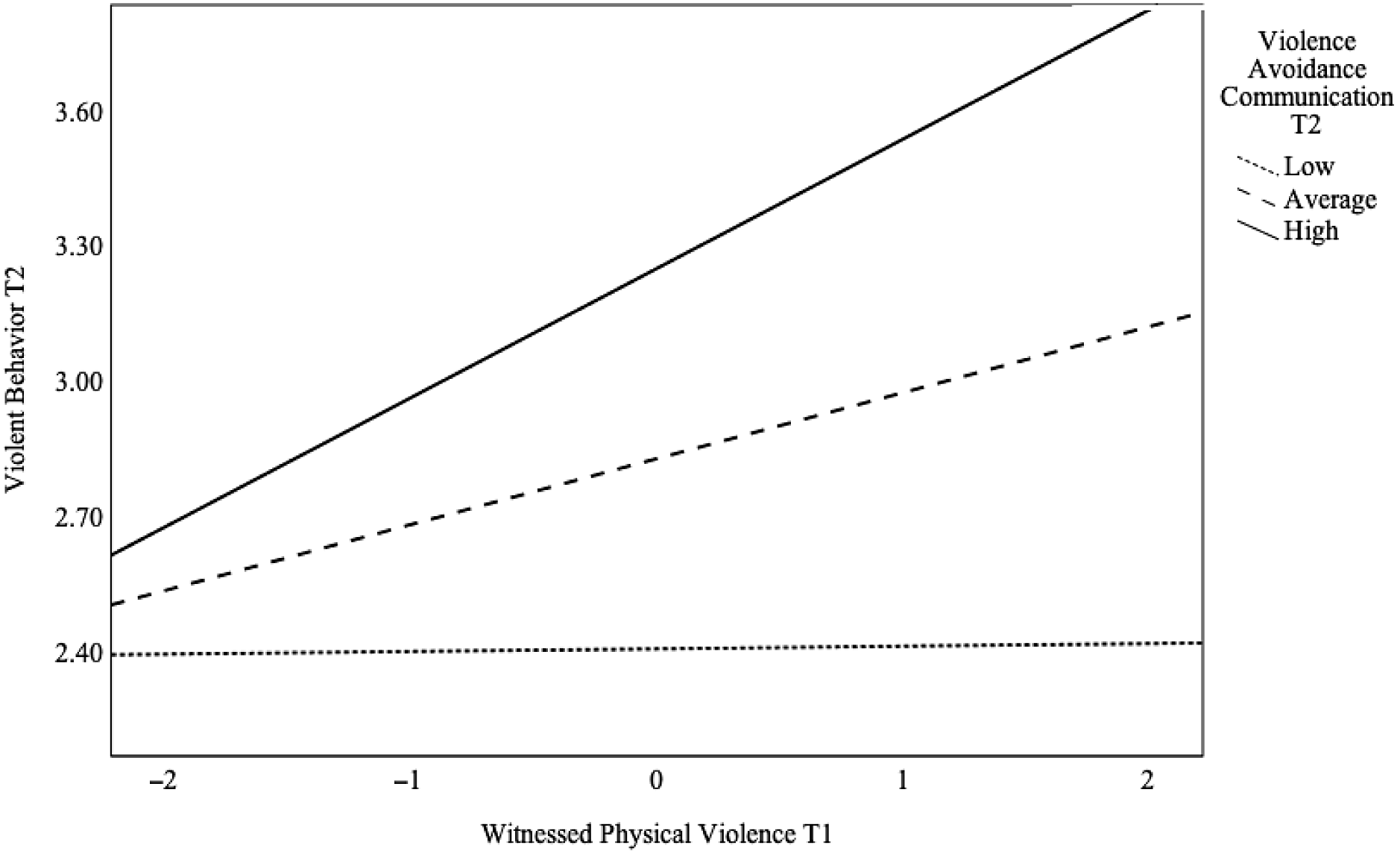

For hypothesis 2b the results showed that at low levels (−1SD) of violence avoidance communication (T1) the effect on the association between witnessed violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2) was not significant [βsimple = 0.006, SE = 0.071, p = 0.931]. However, at average [βsimple = 0.1461, SE = .050, p = 0.004] and (+1SD) high [βsimple = 0.286, SE = 0.065, p < 0.001] levels of violence avoidance communication the effect was positive and significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Conditional effects of violence avoidance communication (T2) on the link between witnessed violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2).

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method and resulting index of moderated mediation further confirmed the significant moderated mediation effect, B = −0.047, SE = 0.025, 95% CI = [−0.107, −0.011], where violence avoidance communication (T1) moderated the link between witnessed violence (T1) and efficacy to avoid violence (T2), as well as witnessed violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2), effectively buffering the influence on violent behavior (T2). The indirect effect of witnessing violence (T1) on violent behavior (T2) via efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was statistically significant for boys with low (−1SD), [B = 0.102, SE = 0.048, 95% CI = (0.033, 0.221)] and average [B = 0. 039, SE = 0.024, 95% CI = (0.002, 0.094)] levels of violence avoidance communication. In contrast, this indirect effect was not significant for boys with high (+1SD) violence avoidance communication, B = −0.023, SE = 0.030, 95% CI = [−0.089, 0.032].

Moderating effect of monitoring on the links between witnessed violence, efficacy and violent behaviors

We tested hypothesis 3 using a similar moderated mediation model with parental monitoring (T2) as the moderator. Parental monitoring (T) did not moderate the link between witnessed violence (T1) and efficacy to avoid violence (T2) (b = −0.103, SE = 0.235, p = 0.662). Parental monitoring also did not moderate the association between witnessed violence (T1) and violent behaviors (T2) B = −0.072, SE = 0.093, p = 0.435. Thus neither hypotheses 3a nor 3b were confirmed. A bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method and resulting non-significant index of moderated mediation further confirmed no significant moderated mediation effect of parental monitoring (T1) on the link between witnessed violence (T1) and violent behavior (T2) via efficacy to avoid violence (T2), [β = 0.015, SE = 0.043, 95% CI = (−0.089, 0.083)].

Discussion

The literature supports the longitudinal link between witnessing physical violence and subsequent violent behaviors. The purpose of this study was to examine this in a sample of African American boys living in under-resourced conditions. We assumed a risk and resilience approach with an ecological lens for this study which makes important statements about how parents can support and protect African America adolescent boys in low-income neighborhoods, particularly against the backdrop of exposure to physical violence. We also focused on the dimensions of parent communication and monitoring. We confirmed that youth’s efficacy to avoid violence is a powerful asset, but witnessing physical violence is a double assault as it is increases violent behaviors while also weakening efficacy to avoid violence. Although exposure to violence is a serious and pervasive risk in low-income and under resourced neighborhoods, and its ability to undermine efficacy is most pernicious, parental communication about specific risks can operate as a resilience resource supporting healthy outcomes for African American adolescent boys in these conditions.

Relationship between witnessing violence and violent behavior

We found that participants who witnessed more physical violence were engaged in more violent behaviors over time. Witnessing physical violence was a significant risk to positive development for African American boys in low-income neighborhoods (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Deatrick, Kassam-Adams and Richmond2011). Our study confirmed a longitudinal trajectory of witnessing physical violence being associated with more violent behavior in this sample of African American low income urban-dwelling adolescent boys. Much of the prior work in this area has been cross-sectional and focused on the effects of domestic violence and television violence (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura and Baltes2009; Orue, et al Reference Orue, Bushman, Calvete, Thomaes, de Castro and Hutteman2011; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Herrenkohl, Moylan, Tajima, Klika, Herrenkohl and Russo2011), and less on acts of personal violence experienced by youth. Witnessing physical violence also had an indirect effect on adolescent violent behavior by deflating internal strengths and cognitive mechanisms – efficacy to avoid violence. Lower perception of one’s efficacy to avoid a risk behavior is related to higher likelihood of engaging in that risk behavior and the negative results of risk exposure.

Mediating role of efficacy to avoid violence

Our mediational model examined the indirect influence of witnessing physical violence on violent behavior over time, via efficacy to avoid violence. The hypothesized mediational relationship was confirmed. When efficacy to avoid violence is high, outcomes and resilience levels are better for African American urban-dwelling boys (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Farrington & Ttofi, Reference Farrington and Ttofi2011; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Todd, Martinez, Coker, Sheu, Washburn and Shah2013). However, deflated efficacy is related to worse outcomes, including engagement in violent behaviors (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a). The experience of witnessing physical violence may tax youths’ coping mechanisms, like efficacy to avoid violence, while also increasing opportunities for engaging in violent behaviors. This heighted risk profile, along with limited adaptive responses, may amplify the likelihood of negative outcomes overtime. In determining the long-term negative trajectory of witnessing physical violence to violent behaviors the role of witnessing violence in undermining efficacy over time emerged as a significant mediator of that negative trajectory. We did not analyze the effect of other intermediate variables so we were unable to compare this effect with any other factors in the longitudinal indirect effect of witnessing violence on violent behavior. The study, however, supports the idea that risks or negative events like witnessing physical violence can undermine youths’ psychological protection system resulting in negative outcomes like violent behaviors. Parents, however, remain critical in supporting the development and enhancement of efficacy beliefs in African American adolescent boys. This specific cognitive asset (efficacy to avoid violence), enhanced by parents’ supportive behaviors, can blunt the negative effects of experiencing violence, and stimulate and sustain positive youth development.

Violence avoidance communication as a moderator

Probably one of the most important findings of this study is the promotive effect of parent’s violence avoidance communication on the association between witnessing violence and efficacy to avoid violence. Previous studies have identified parent expectations of non-violence as critical to understanding violent behavior among African American adolescent boys who witness physical violence (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a). We found that more parental violence avoidance communication was associated with greater efficacy to avoid violence. Parental violence avoidance communication also moderated the negative link between witnessing violence and efficacy to avoid violence, especially for African American boys who had higher levels of witnessed violence (T1). Efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was higher when the boys in our study had witnessed few acts of violence (T1), regardless of level of communication about violence (T2), but for African American boys who had witnessed more violent behavior at (T1) efficacy to avoid violence (T2) was higher if they had also received more violence avoidance messages (T2). However, we also observed a positive association between parents’ violence avoidance communication and youth violent behaviors, suggesting that adolescents who receive more anti-violence messages from their parents engage in more violence. African American adolescent boys in this sample who had witnessed fewer acts of violence (T1) and had received less violence avoidance communication (T2) were less likely to engage in violent behavior (T2). Those who had witnessed more violence (T1), and received more parental violence avoidance communication (T2) were more likely to engage in violent behaviors (T2), suggesting that talking to adolescents about avoiding violence may be linked to worse outcomes. Nonetheless, this explanation is not supported by the correlation between these two factors. In fact, a better explanation for this non-intuitive link is that the frequency of parents’ messages about violence is a protective response to the level of violence that African American adolescent boys in areas of concentrated disadvantaged might report (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Henry, Mays and Schoeny2011). Further, parents’ violence avoidance messages were positively linked to boys’ efficacy to avoid violence.

Parental monitoring as a moderator

Our study found that parental monitoring did not help explain the link between witnessed violence and later violent behaviors for the low-income African American boys in this sample. The literature is divided on whether parent monitoring or involvement can potentially avert the negative development of adolescents who had been exposed to physical violence. Some researchers argue that parental involvement and monitoring reduce adolescent delinquent behavior (Keijsers et al., Reference Keijsers, Frijns, Branje and Meeus2009; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Caldwell, Assari, Jagers and Flay2016a; Neppl et al., Reference Neppl, Dhalewadikar and Lohman2016; Gaylord-Harden et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan and Murry2018). Others have countered that monitoring that includes activities like solicitation of knowledge and disclosure does not trump adolescent personality in explaining delinquency and externalizing problems, especially in the realm of criminal delinquency (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Krueger, Johnson, McGue and Iacono2009). While we could not account for externalizing problems and youth temperament, our study seems to support the camp that suggests that, at least in the presence of other specific parenting behaviors like violence avoidance communication, parental monitoring may not offer any additional protections for youth, or enhancement of youth efficacy to avoid violence.

Although monitoring did not emerge as significant in this study, we demonstrate that parental violence avoidance communication is positively linked to higher efficacy to avoid violence, and that it moderates the association between witnessing violence and efficacy to avoid violence. Efficacy to avoid violence is linked to fewer violent behaviors, confirming the literature on the role of parents as key shapers of youth behaviors, and specifically as influencers of youth decisions to engage in violent acts (Lindstrom Johnson et al., Reference Lindstrom Johnson, Finigan, Bradshaw, Haynie and Cheng2011; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Mays, Bettencourt, Erwin, Vulin-Reynolds and Allison2010; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Henry, Mays and Schoeny2011; Neppl et al., Reference Neppl, Dhalewadikar and Lohman2016; Thomas & Hope, Reference Thomas and Hope2016). The existing literature has attempted to map the trajectory from violence exposure to engagement but the focus on youth efficacy to avoid violence, and especially for African American adolescent boys in poor urban contexts, remains limited.

Our results highlight the importance of parents as critical influencers of the behaviors of African American adolescent boys who are exposed to violence. Specifically, these findings support the call for strategies that enhance parents’ efforts and resources, towards facilitating more frequent communication about risks, and limiting youths’ opportunity for exposure to risks that may be community dependent. However, early access to better resources has to be translated into supportive parenting behaviors that encourage youth efficacy or strengths to evidence an effect on negative outcomes.

Limitations, strengths, and future directions

Our findings suggest that risk communication specific to violence, but not parental monitoring, is linked to fewer youth violent behaviors. This finding affirms the importance of crucial socialization agents, like parents, in influencing youth behaviors (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1979; Hawkins & Weis, Reference Hawkins and Weis2017). There are some limitations to this study, one of which is the use of a half-longitudinal model to examine mediation effects. Selig and Preacher (Reference Selig and Preacher2009), Cole and Maxwell (Reference Cole and Maxwell2003), and Fritz and MacKinnon (Reference Fritz, MacKinnon, Laursen, Little and Card2012) have discussed reasons why longitudinal data are required for developmental research particularly in testing mediational hypotheses, and we acknowledge that although three time points is preferred this study used two. Like other half-longitudinal studies, however, (e.g. Brady et al., Reference Brady, Gorman-Smith, Henry and Tolan2008; Gaylord-Harden, So, et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, So, Bai, Henry and Tolan2017) we used two time points of data to construct a two-wave study (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003). While development research, by default, requires multiple observations over time, and most ideal testing of mediation models requires at least three time points (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003) two waves of data or half-longitudinal designs are also acceptable and have been used successfully in mediational research on youth violence exposure (e.g., Gaylord-Harden, So, et al., Reference Gaylord-Harden, So, Bai, Henry and Tolan2017; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Felix, Halpert and Petropoulos2009).

Although we rely on adolescent self-reports of our main outcome variables, these kinds of self-reports are a generally accepted measurement of youths’ own experiences and behaviors, especially with the awareness that they may often select which experiences to report to parents and other adults. Additionally, these data are from African American boys from under resourced urban neighborhoods and thus do not represent the experiences of all African American adolescents or all African American adolescent boys.

Although the findings from this study are instructive on parental influences on positive youth development the measures of parental monitoring and violence avoidance communication are both limited. The narrow variance in both measures (violence avoidance communication and parental monitoring) do not allow for an appreciation of variability in the extent to which parents engage in these behaviors. The low internal consistency of the monitoring measure and limited face-validity of the communications are also limitations, but the data allow access to a unique sample and conditions for examining these issues. However, more robust measures of parenting behaviors will likely result in a more comprehensive analysis of the effects of parenting behaviors on adolescent strength-based coping and development. Another limitation is the absence of context for self-reported physical fighting, the more commonly reported behavior. It may well be that participants are reporting normative physical sibling and peer tiffs as violence, thus inflating the measurement. Finally, our analysis did not address how age and parental education alter the associations of interest. For example, the relations between witnessing violence, perceived self-efficacy, and engagement in violent act may vary substantially for early adolescence compared to mid and late adolescence.

Our study also did not account for the role of the neighborhood and social structure on parents, and the indirect effect on parenting behaviors. Low-income urban communities are characterized by inequities and inequalities that are a result of a long history of racism and segregation and the additional severe and chronic stressors borne out of these systemic pressures. Parents and families in these situations are also influenced by these oppressive systems, therefore, systemic change (i.e., elimination of inequality, racism, and poverty) is required to adequately address the negative trajectories described in this paper. Notwithstanding these limitations however, the findings of this study raise important considerations for researchers and those who work with African American youth and families.

Conclusion

In poor urban contexts the positive development for African American adolescent boys is under constant threat from risks like witnessing physical violence. While much of the research has applied a pathological lens, this study focused on a strengths-based approach. Our findings suggest practical ways to boost intervention efforts directed at African American boys living in environments where they are at risk for exposure to violence. A focus on building and enhancing the self-efficacy to avoid violence may be key to strengthening and supporting positive youth development. Fostering parents’ risk communication introduces an area for promising interventions. Such interventions may reduce acts of violence by enhancing the risk avoidance efficacy of African American adolescent boys. Such programs may interrupt the process through which exposure to violence contributes to a long-term trajectory of violence. Design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions that leverage parental education and risk communication is the next logical step in promoting positive development of African American boys in urban settings. An equally, if not more important line of primary intervention is attending to the causes (e.g., institutional discrimination, economic barriers, employment inequalities, and education access and inequities) that sustain youth violence in the first place, along with the secondary intervention of targeting self-efficacy by way of parent efforts. However, strengthening existing parent supports that can enhance youth assets in tandem with primary preventative interventions may be the most ideal approach. Still, the solution to violence exposure does not reside solely in perceived damaged self-concepts of African American boys or in their parents’ communication strategies. Such a narrow focus would ignore the impactful structural and institutional antecedents of the disproportional impact of this public health risk on African American youth and families in under resourced neighborhoods.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422000098

Acknowledgments

This work is based on data from the Aban Aya Youth Project supported by grants to Brian R. Flay (P.I.) from the Office of Minority Health administered by the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (U01HD30078) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA11019). This manuscript is of the last works of Brian Flay. He died prior to its acceptance for publication, but we are grateful for Brian’s passion and support for this work.

Conflicts of interest

None.