Fifteen million children are exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) in their lifetimes (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck and Hamby2015). This form of violence is characterized by physical and sexual assault, psychological aggression, and stalking that occurs between current or former romantic partners (Breiding et al., Reference Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black and Mahendra2015). Young children are at especially high risk for witnessing IPV given the time they spend at home and proximity to their caregivers (Fantuzzo & Fusco, Reference Fantuzzo and Fusco2007; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck and Hamby2015). The negative effects of early-life IPV exposure are enduring (Galano et al., Reference Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Clark, Stein and Graham-Bermann2019; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Moschella, Hamby and Banyard2020), suggesting an urgent need to delineate contributors to children’s adjustment following these experiences to inform strategies for mitigating the negative consequences of exposure.

Children who witness IPV are at increased risk of experiencing a myriad of adjustment problems, including the development of significant emotional and behavioral disturbance. Yet, many children also display resilience following these experiences – that is, positive adaptation despite exposure to IPV (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009). Interventions have been developed to address the impact of IPV on adjustment problems and to promote resilience, yet little is known about the durability of the effects of intervention on child outcomes. Further, although adjustment problems and resilience often co-occur, few studies have examined their shared risk and promotive factors. Delineation of said factors can inform intervention approaches to simultaneously reduce negative outcomes and enhance positive outcomes following IPV exposure. Thus, the current study has two primary aims: 1) to assess the long-term effects of intervention in a sample of children exposed to early-life IPV; 2) to identify which individual- and parent-level risk and promotive factors contribute to both behavior problems and resilience trajectories among IPV-exposed children.

Conceptualizing risk and resilience

This work is informed by a developmental psychopathology framework, which emphasizes the importance of examining how both context and individual processes contribute to adaptive and maladaptive outcomes throughout development (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2016; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti, Toth and Cicchetti2016; Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009). Studies on the impact of violence and adversity, including IPV, often focus on one versus the other, giving an incomplete view on children’s functioning. Research has also demonstrated that resilience and psychopathology may occur simultaneously (Miller-Graff et al., Reference Miller-Graff, Scheid, Guzmán and Grein2020; Whittaker et al., Reference Whittaker, Harden, See, Meisch and Westbrook2011), suggesting that a concurrent examination of these processes may yield a greater understanding of their shared and unshared mechanisms. As such, this work focuses on risk and promotive factors at both the individual- and family-level and examines adjustment problems and resilience as co-occurring processes. Consistent with prior research, we define risk factors as individual and environmental characteristics that lead to more maladaptive outcomes or undermine positive adaptation (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth2009; Masten, Reference Masten2014). Conversely, promotive factors are positive individual and environmental characteristics that operate independently from and in the opposite direction of risk factors – that is, they foster resilience or curb the development of maladaptive outcomes (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2013). These positive individual and environmental inputs are deemed protective factors when they buffer against the effects of risk factors. Said another way, protective factors moderate the effects of risk factors on either adaptive or maladaptive outcomes (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2013).

Common conceptualizations of maladaptive outcomes focus on psychopathology and/or behavior problems. In childhood, internalizing problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) and externalizing problems (e.g., aggression, delinquency) are often used as broad indicators of adjustment problems, especially given that they predict the emergence of later psychopathology (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Young and Hankin2017). While children do experience other forms of psychopathology following IPV exposure (e.g., PTSD), these two overarching categories give a fairly comprehensive snapshot of children’s compromised functioning (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). Conceptualizing resilience is more difficult. Early work on resilience, particularly in adults, defined resilience as hardiness (the absence of psychopathology) or the ability to “bounce back” (some symptoms with a relatively quick return to baseline; Southwick et al., Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and Yehuda2014). Yet, work from other resilience theorists, particularly those focused on children, highlight that this definition fails to capture the presence of adaptive functioning in the context of adversity and thus propose that resilience is, “…the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten system function, viability, or development” (Masten, Reference Masten2014, p. 6; Southwick et al., Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and Yehuda2014). Thus, we define resilience in terms of adaptive behaviors rather than as the absence of psychopathology.

Emotion regulation and prosocial behavior are two aspects of adaptive functioning that have been used to assess resilience in children (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010). Emotion regulation – the ability to recognize and down- or up-regulate affective states – is a key competency that goes through a period of rapid development beginning in the preschool period and continues to develop throughout early and middle childhood (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Wolfe, Diaz, Liu, LoBue, Perez-Edgar and Buss2017; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Ram, Buss, Cole, Helm and Chow2018). Prosocial behaviors are defined as voluntary behaviors intended to benefit another person, as well as the inhibition of anti-social behaviors (Koenig et al., Reference Koenig, Cicchetti and Rogosch2004). Children’s prosocial behaviors have implications for their success at meeting expectations for social interactions, as well as their overall social development (Caputi et al., Reference Caputi, Lecce, Pagnin and Banerjee2012; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Deng and Chen2019) and are thus key aspects of children’s social-emotional competence. Returning to the definition of resilience as successful adaptation in the face of threats to a system, we define resilience in this study as greater emotion regulation and prosocial behaviors over time.

Early intervention as a promotive factor

Several interventions have been designed to disrupt the development of psychopathology and promote resilience in IPV-exposed children (Rizo et al., Reference Rizo, Macy, Ermentrout and Johns2011). However, few specifically target children in the preschool period, which is a critical developmental window (Fantuzzo & Fusco, Reference Fantuzzo and Fusco2007; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Castor, Miller and Howell2012; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Moschella, Hamby and Banyard2020). One such intervention is the Preschool Kids’ Club (PKC; Graham-Bermann, Reference Graham-Bermann2000). This 10-session group program is designed specifically for children ages 4–6 who have witnessed IPV. The aims of the program are for children to develop skills for identifying and regulating emotions; reframing maladaptive cognitions around IPV (e.g., self-blame); and learning safety planning and non-violent conflict resolution skills. The PKC is offered in tandem with the Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP) a 10-session group intervention for mothers who have experienced IPV (Graham-Bermann, Reference Graham-Bermann2012). The focus of the MEP is on processing mothers’ lifetime histories of trauma exposure, including IPV, increasing knowledge of and access to formal and informal supports, and enhancing parenting skills. Evaluations of the PKC offered together with the MEP have demonstrated that the PKC significantly reduces children’s internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as enhances children’s social competencies in the 6–8 months following the intervention (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Stein and Graham-Bermann2021a; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Lynch, Banyard, DeVoe and Halabu2007; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Miller-Graff, Howell and Grogan-Kaylor2015; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Miller, Lilly and Graham-Bermann2013). Participation in the MEP is associated with short-term positive effects on mothers’ functioning, including reducing mental and physical health problems as well as enhancing parenting skills (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Howell, Miller-Graff, Galano, Lilly and Grogan-Kaylor2019; Grogan-Kaylor et al., Reference Grogan-Kaylor, Galano, Howell, Miller-Graff and Graham-Bermann2019a; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Miller, Lilly, Burlaka, Grogan-Kaylor and Graham-Bermann2015), which might promote long-term positive adjustment in their children.

An important potential effect of early intervention is to promote well-being in later development. The only way to capture these outcomes is to examine the effects of interventions after several years. Yet, few studies have examined the effects of intervention participation on IPV-exposed children’s outcomes more than 1 year following the conclusion of treatment. One such long-term intervention evaluation was conducted on Project SUPPORT, an intervention specifically designed to treat conduct problems in children experiencing IPV (Jouriles et al., Reference Jouriles, McDonald, Spiller, Norwood, Swank, Stephens and Buzy2001; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Jouriles and Skopp2006). Mothers of children ages 4–9 participated in the Project SUPPORT intervention following a stay at a domestic violence shelter and completed several follow-up assessments for 2 years after the conclusion of the intervention (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Jouriles and Skopp2006). At the end of the 2-year follow-up period, children whose mothers received the Project SUPPORT intervention had significantly fewer conduct problems and internalizing problems than children whose mothers did not receive the intervention. Moreover, children in the intervention condition had better social relationships than children in the comparison condition (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Jouriles and Skopp2006). Notably, the PKC, offered jointly with the MEP (MEP + PKC), shares common elements with Project SUPPORT, including a focus on building support systems and enhancing parenting. The MEP + PKC additionally includes a child-focused component designed to help children build coping and emotion regulation skills, as well as process their experiences related to IPV. The combination of the MEP + PKC yields the most positive effects on child outcomes in the short-term (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Lynch, Banyard, DeVoe and Halabu2007). Thus, it is possible that participation in the MEP + PKC in early development would lead to enhanced functioning in later development; however, this has not been empirically tested. To address the need for a longer-term evaluation of the effectiveness of the MEP + PKC, this study traces outcomes approximately 8 years following early intervention, when children have primarily transitioned into early adolescence. Given that this is a time of increased risk for involvement in violence (e.g., youth violence, teen dating violence) and the development of mental health problems (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Getz and Galvan2008; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2005), it is important to understand to what extent, if any, early intervention has on outcomes during this period of development. Empirical studies on the long-term effects of brief, early intervention can inform how we think about violence prevention and intervention throughout childhood as well as help improve policy around addressing violence for at-risk youth.

Individual, environmental, and maternal risk and promotive factors

Several risk and promotive factors have been identified among violence-exposed children (Vu et al., Reference Vu, Jouriles, McDonald and Rosenfield2016; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). Given our emphasis on both symptoms of psychopathology and indicators of resilience, we chose to focus on factors that might have implications for both types of outcomes. This approach has the potential for identifying cross-cutting risk and promotive factors that, if targeted, can both improve psychopathology and enhance resilience. Moreover, as both theory and evidence point to the importance of caregivers and the broader family environment for child adjustment, we examined risk and promotive factors at both the individual level as well as within the child’s social ecology. These considerations drove the selection of the factors included in this study.

Childhood irritability

Childhood irritability is generally defined as an elevated proneness to anger relative to peers and is a common reason for psychiatric referral in youth (Brotman et al., Reference Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine and Leibenluft2017). In community samples of non-IPV-exposed youth, irritability has been associated with increased risk for later internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Considering that IPV exposure is associated with higher levels of irritability over time (Wiggins et al., Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris and Leibenluft2014), this construct may play an especially important role in shaping the trajectory of children’s adjustment. Yet, few studies have prospectively examined how irritability contributes to behavior problems or undermines resilience following exposure to IPV.

IPV exposure

Different characteristics of childhood IPV exposure have been associated with risk for poorer mental health outcomes. More severe IPV exposure as well as earlier age of first exposure predict higher internalizing and externalizing problems (Graham-Bermann & Perkins, Reference Graham-Bermann and Perkins2010). Less clear, however, is whether these IPV characteristics still predict outcomes when other individual and family factors are considered, with some work demonstrating that they do (Miller-Graff et al., Reference Miller-Graff, Scheid, Guzmán and Grein2020) and other work that they do not (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009). More severe IPV exposure has also been found to undermine resilience in cross-sectional studies (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010). Together, these studies suggest that IPV exposure severity might have greater effects on pathways to behavior problems than on pathways to resilience when considering multiple risk and protective factors.

Caregiver mental health

Numerous studies have focused on the impacts of caregiver mental health on child adjustment. Separate work has investigated the effects of caregiver posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) on child functioning. Greater caregiver PTSS (Jouriles et al., Reference Jouriles, McFarlane, Vu, Maddoux, Rosenfield, Symes, Fredland and Paulson2018; Scheeringa et al., Reference Scheeringa, Myers, Putnam and Zeanah2015) and caregiver depression (McFarlane et al., Reference McFarlane, Symes, Binder, Maddoux and Paulson2014; Miller-Graff et al., Reference Miller-Graff, Scheid, Guzmán and Grein2020) have been frequently associated with greater risk for psychopathology in children, including PTSD, internalizing, and externalizing behavior problems. While this effect may be partially mediated by negative parenting behaviors, there still appear to be direct effects of caregiver PTSS on child functioning. Similarly, higher caregiver PTSS (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009) and depression (Martinez-Torteya et al., Reference Martinez-Torteya, Anne Bogat, Von Eye and Levendosky2009) can undermine resilient functioning in children exposed to IPV. The limited work examining caregiver depression and PTSS separately has found differential effects of caregiver depression and PTSS on children’s adjustment profiles and resilient functioning (Galano et al., Reference Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Clark, Stein and Graham-Bermann2019; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009). More common approaches to research in this area include examining caregiver mental health as a latent factor (e.g., Levendosky et al., Reference Levendosky, Leahy, Bogat, Davidson and von Eye2006) or only examining one area of mental health (e.g., depression; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Gavidia-Payne, Brown and Giallo2019). A more nuanced understanding of the effects of caregiver depression versus PTSS on child functioning can help better inform dyadic- and family-based strategies for intervening with IPV-exposed children.

Parenting

Negative parenting practices (e.g., corporal punishment, hostility) in the context of IPV have been associated with greater internalizing and externalizing problems (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Kim and Fisher2012; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Chan, McCarthy, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2018; Symes et al., Reference Symes, Mcfarlane, Fredland, Maddoux and Zhou2016). Findings specifically focusing on positive parenting (e.g., warmth, involvement) are more mixed. While some research has found that positive parenting behaviors lead to fewer internalizing and externalizing problems in their children following adverse childhood experiences (Gewirtz et al., Reference Gewirtz, DeGarmo and Medhanie2011; Miller-Graff et al., Reference Miller-Graff, Scheid, Guzmán and Grein2020); findings in samples of children exposed specifically to IPV have found no buffering effect of positive parenting on child adjustment (Coe et al., Reference Coe, Parade, Seifer, Frank and Tyrka2020; Galano et al., Reference Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Clark, Stein and Graham-Bermann2019). More limited work has examined the role of parenting in promoting resilience. One recent study found that greater positive parenting was associated with better child prosocial skills (Miller-Graff et al., Reference Miller-Graff, Scheid, Guzmán and Grein2020). However, in a longitudinal study, positive parent-child relationships and positive parent discipline were related to concurrent child prosocial behavior, but did not predict future prosociality (Pastorelli et al., Reference Pastorelli, Lansford, Luengo Kanacri, Malone, Di Giunta, Bacchini, Bombi, Zelli, Miranda, Bornstein, Tapanya, Uribe Tirado, Alampay, Al-Hassan, Chang, Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Oburu, Skinner and Sorbring2016). Thus, while negative parenting seems to be a shared factor affecting both behavior problems and resilience, the role of positive parenting in these processes is less clear.

The current study

The goal of the current study is to examine children’s trajectories of behavior problems and resilience following early-life exposure to IPV to identify factors that support or undermine positive adaptation. The guiding research questions are:

-

1. What effect does an early, brief intervention have on adjustment trajectories, approximately 8 years later?

-

2. Across a variety of individual- and family-level risk and protective factors, which matter most for maladaptive outcomes? For adaptive outcomes? For both?

Methods

Participants

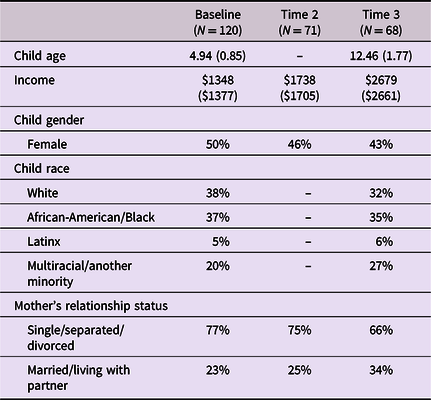

Data for this study were drawn from a sample of 120 children and their caregivers who participated in a randomized controlled trial of an intervention for IPV-exposed families. At baseline, the children were an average age of 4.94 years (SD = 0.85), with 50% girls. The sample was ethno-racially diverse with 38% identifying as white, 37% as Black or African American, 20% as Multiracial, and 5% as Latinx. Children came from primarily low-income families, with a baseline average family monthly income of $1348 (SD = $1377). At the time of the fourth follow-up interview (approximately 8 years following the initial interview), 68 families were able to be located and consented to participate, with average child age of 12.46 (SD = 1.77). Of these 68 families, 35 were in the Intervention condition and 33 were in the Control condition (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sample demographic information across the four time points

Note. Some information not collected at all time points.

Procedures

Families were recruited throughout Southeast Michigan and Ontario, Canada using flyers posted at various businesses, clinics, and domestic violence shelters. Interested mothers called a study number to get more information about participation and be screened for eligibility. Families were eligible if the mother screened positive for a history of IPV victimization within the past 2 years and had a child in the target age range (4–6). If eligible families wanted to enroll, they were randomly assigned to the intervention or wait-list control condition. This was done using a block randomization procedure such that the first six families were in the intervention condition, the following six were in the control condition, and so forth. The intervention was delivered in 10 sessions over a 5-week period. Groups were led by graduate-level students in psychology and social work and co-led by advanced undergraduate students. All group leaders received weekly supervision from the program developer and licensed clinical psychologist to ensure intervention fidelity.

To evaluate the effects of the intervention, mothers and children participated in four interviews over the course of the study: baseline, immediately post-intervention (5 weeks from baseline), 6–8-months post-intervention, and approximately 8 years post-intervention. This study utilizes data from the baseline (Time 1), 6–8 month follow-up (Time 2), and 8 year follow-up (Time 3) interviews. Data from the interview immediately post-intervention are not used in the current study as not all predictors of interest were assessed at this time point. Moreover, only caregiver-reported data were used in these analyses, as children did not provide information on the constructs of interest in this study. The Time 1 and Time 2 assessments were designed to capture intervention effects, as prior trials suggested that effects might not be evident until several months following the conclusion of the intervention (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Stein and Graham-Bermann2021a; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Miller-Graff, Howell and Grogan-Kaylor2015). The Time 3 assessment was added post-hoc based on the authors’ interest in long-term adjustment following early-life violence exposure and long-term intervention effects. Thus, the spacing between Times 2 and 3 was not planned as part of the study design. At each interview, mothers answered questions about parenting, her recent IPV exposure, and mental health symptoms, as well as demographic information. Mothers also reported on their child’s behavior problems and resilience at each interview. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board prior to data collection.

Measures

Child resilience

The Social Competence Scale (SCS) – Parent Version is a 12-item caregiver-report questionnaire (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group [CPPRG], 2002). Items assess caregivers’ perceptions of child behaviors in social settings and fall into two categories: emotion regulation skills and prosocial/communication skills. Caregivers rate the degree to which each statement describes their child using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1’ Not at all to ‘5’ Very well. This measure demonstrates good psychometric properties with preschool-age children and is appropriate for use in high-risk samples (Gouley et al., Reference Gouley, Brotman, Huang and Shrout2008; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010). This measure has also demonstrated good reliability in assessing social competence in older childhood and adolescence (Brajša-Žganec et al., Reference Brajša-Žganec, Merkaš and Šakić Velić2019; Derella et al., Reference Derella, Johnston, Loeber and Burke2019; López-Romero et al., Reference López-Romero, Romero and Andershed2015). Internal consistency for the current study for the prosocial/communication skills subscale was (α) 0.83 at baseline, (α) 0.87 at Time 2, and (α) 0.86 at Time 3. Reliability for the emotion regulation skills subscale was (α) 0.74 at baseline, (α) 0.83 at Time 2, and (α) 0.84 at Time 3.

Child behavior problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) ages 4–18 is a 113-item caregiver-report measure that is widely utilized to assess a broad range of socio-emotional and behavioral difficulties in children (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991). Each item asks caregivers to rank the extent to which the behavior described is true of their children, from ‘0’ ‘Not True’ to ‘2’ ‘Very or often true.’ Answers are summed to create the internalizing problems (depression/withdrawal, depression/anxiety, somatic complaints) and externalizing problems (aggression, delinquent behavior) scales. Three items from the externalizing problems scale were removed to create the irritability measure (see next section). The CBCL demonstrates good psychometric properties across a broad age range (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991). Reliability for the internalizing problems scale was (α) 0.90 at Time 1, (α) 0.86 at Time 2, and (α) 0.87 at Time 3; and (α) 0.92 at Times 1 and 2, and (α) 0.90 at Time 3 for the externalizing problems scale.

Childhood irritability

Child irritability was also assessed using the caregiver-report CBCL ages 4–18. The empirically-derived CBCL irritability score (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Bonadio, Bearman, Ugueto, Chorpita and Weisz2019; Roberson-Nay et al., Reference Roberson-Nay, Leibenluft, Brotman, Myers, Larsson, Lichtenstein and Kendler2015; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan and Eley2012) sums three items assessing irritable mood, sudden changes in mood, and temper outbursts. The parent-report CBCL irritability score has been used with preschoolers and adolescents; and demonstrates acceptable reliability, convergent validity, and structural invariance over time (Roberson-Nay et al., Reference Roberson-Nay, Leibenluft, Brotman, Myers, Larsson, Lichtenstein and Kendler2015; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan and Eley2012; Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Moroney, Machlin, Roberson-Nay, Hettema, Carney, Stoddard, Towbin, Pine, Leibenluft and Brotman2017). Reliability was (α) 0.83 at Time 1, (α) 0.81 at Time 2, and (α) 0.80 at Time 3.

IPV victimization severity

The Conflict Tactics Scale – Revised (CTS-2; Straus et al., Reference Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy and Sugarman1996) assessed past-year frequency of IPV, including 39 violence victimization questions. Caregivers reported the frequency at which different events occurred on the following scale: never, one time, two times, 3–5 times, 6–11 times, 12–20 times, or more than 20 times. Answers are recoded to reflect the mid-point of each category, and responses are summed across the items for a total IPV exposure score (which includes physical and sexual violence, psychological aggression, and injury). The CTS-2 has good validity and reliability in reporting partner violence (Straus et al., Reference Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy and Sugarman1996). Although the reliability of using this measure to assess IPV perpetration in women has been called into question (Hamby, Reference Hamby2016; Lehrner & Allen, Reference Lehrner and Allen2014), this is not true for the measurement of IPV victimization, which is the focus in this study. Reliability for the total scale was (α) 0.93 at baseline, (α) 0.85 at Time 2, and (α) 0.84 at Time 3.

Maternal PTSS

The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) assesses the frequency of PTSS over a one-month period in adults (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Cashman, Jaycox and Perry1997). Possible responses range from ‘0’ ‘Not at all or only one time’ to ‘3’ ‘5 or more times per week/almost always.’ A total symptom severity score is the sum of responses to each item. Higher scores reflect greater PTSS, with scores over 20 falling in the moderate-severe range. The PDS has been shown to have strong, positive correlations with other validated measures of PTSS and good internal consistency for the total scale (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Cashman, Jaycox and Perry1997). Reliability at Times 1 and 2 was (α) 0.89; (α) 0.92 at Time 3.

Maternal depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item questionnaire that assesses depression symptoms over the past week (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). Answers are given on a Likert-type scale from ‘1’ ‘None of the time’ to ‘4’ ‘Most or all of the time.’ Higher scores reflect higher symptom frequency, and scores greater than 16 reflect likely clinical levels of symptoms. Reliability at Time 1 and 3 was (α) 0.92; (α) 0.89 at Time 2.

Parenting behaviors

The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) is a 42-item self-report questionnaire measuring both negative and positive parenting practices (Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Frick and Wootton1996). The positive parenting subscale assesses parent involvement in children’s activity, use of warmth and positivity during interactions with their child, and their use of appropriate disciplinary strategies (e.g., timeout). The negative parenting subscale assesses inconsistent disciplinary practices (e.g., discipline is dependent on parental mood), poor monitoring of children’s location and behavior, and use of corporal punishment. Using a Likert-type scale from ‘1’ ‘Never’ to ‘5’ ‘Always’, higher scores represent more frequent use of parenting practices. The APQ has demonstrated internal consistency and reliability for most subscales, with moderate reliability for the Corporal Punishment subscale (Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Frick and Wootton1996). Although initially designed for parents of children ages 6–18, the APQ has been demonstrated to have good psychometric properties in samples including children as young as age four (Dadds et al., Reference Dadds, Maujean and Fraser2003). Reliability at Time 1 was: Positive Parenting (α) 0.80, Negative Parenting (α) 0.71; at Time 2 Positive Parenting (α) 0.82, Negative Parenting (α) 0.75; and at Time 3 Positive Parenting (α) 0.81, Negative Parenting (α) 0.76.

Analytic plan

Attrition and baseline differences between the intervention and control group were examined using t-tests, ANOVAs, and χ2 analyses. Following these analyses, multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to analyze the longitudinal trajectory of children’s resilience and behavior problems, using person-scores at each timepoint as the level 1 units of measurement, and the individual as the grouping, or level 2 unit of measurement. The first sets of models examined the effects of intervention participation on problem behavior and resilience trajectories, creating separate models for the two resilience subscales as well as the internalizing and externalizing subscales of the CBCL. The predictors included in these models were: time (measured in years), intervention assignment, and a time by intervention interaction term. This last term assesses the association of intervention participation with trajectories and is the predictor of interest in the models testing intervention effects. Nine families from the waitlist control condition elected to participate in the intervention. This change in treatment group assignment occurred between the first and second interview and was modeled in the MLMs. Intervention MLMs also included random effects terms to examine individual heterogeneity in behavior problem and resilience trajectories.

Next, a series of four models examined the effects of individual, environmental, and maternal factors on children’s behavior problems and resilience over time. The dependent variables for the behavior problem models were internalizing and externalizing problems and for the resilience models were emotion regulation and prosocial behavior. Each MLM included the same set of predictors: time (measured in years), child sex, irritability, IPV frequency scores, mother’s mental health (PTSS and depression symptoms), and mother’s parenting. Child sex was included in each model given baseline sex differences in scores.

To account for the multiple comparisons made in these analyses, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995). This approach controls for the false discovery rate (FDR) – the proportion of significant findings within a given set of analyses that are actually null (i.e., false discoveries). The BH procedure focuses on lowering risk for Type I error alongside retaining analytical power (Bejamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Feng and Yi2017). This makes the BH procedure especially useful when examining exploratory questions, as is the case in the current study. To apply the BH procedure, a critical value is calculated based on the ranked order of p-values across all tests, the total number of tests, and the FDR. Estimated p-values are then compared to these critical values, and the largest p-value smaller than the critical value, as well as all p-values ranked above that one, are deemed significant. Adjustments were made separately for research questions one and two, for a total of 36 and 34 ranked p-values, respectively. The FDR was set to 5% for both sets of adjustments, meaning for every twenty significant findings, one would be expected to be actually null.

Power analysis

We base our power analysis (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; Champely, Reference Champely2018) upon the hypothesized correlations in our data. For most of the effects that we are estimating, we anticipate a correlation of at least 0.3. Power calculations, with assumptions of significance level of 0.05, and power of 0.8, suggest that we will require 84 individuals in the sample. Our number of participants is 120. On average, participants were observed for 2.5 waves of the study. Thus, we have 120 × 2.5 = 300 observations. However, these observations are not statistically independent requiring computation of a design effect based upon the intercorrelation of these observations. Following the Public Health Action Support Team (2019), our estimate of the design effect is 1.87 (based on ICC = .58) yielding (from these 300 repeated observations), an effective sample size of 160 observations, providing sufficient statistical power to carry out our analyses.

Results

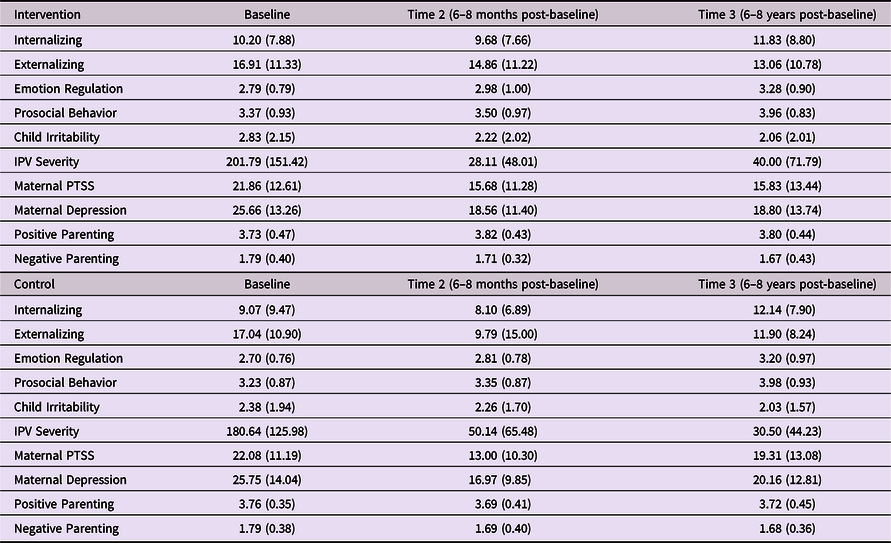

Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics for all study variables, revealing no significant differences between the intervention and control groups at baseline. We also calculated T-scores using published norms for CBCL scores (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991). At time 1, approximately 21% of the sample had internalizing problem T-scores above 70, while 29% had externalizing problem T-scores in this range. By time 2, 20% had internalizing T-scores above 70, while 24% had externalizing scores in this range. At the final time point, 27% had internalizing T-scores above 70, and 19% had externalizing T-scores above 70.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of outcome and predictor variables at each time point

Note. There were no differences at baseline between the intervention and comparison condition (significance level of p < .05).

Attrition analyses

There was moderate retention over 8 years for study participants, such that 57% of the original sample completed the third interview. Notably, we maintained similar sample sizes at Time 2 (n = 71) and Time 3 (n = 68). There was a marginal difference in baseline child age between families present and not present at Time 3; children present at Time 3 were younger at baseline than children not present (t (118) = 1.97, p = .051). They did not differ in baseline income, sex, or race, nor were significant baseline differences found between children who participated at Time 3 versus those that did not on any of the predictor and outcome variables of interest in the current analyses.

Multilevel model results

Unconditional models were run for each dependent variable of interest (prosocial behavior, emotion regulation, internalizing, and externalizing) to assess the appropriateness of MLM and calculate intraclass correlations (ICC). Across all models, an MLM was a better fit than a single-level model. ICCs ranged from 0.54 (prosocial behavior) to 0.58 (emotion regulation and internalizing) to 0.60 (externalizing), indicating that between 54–60% of the differences in behavior problem and resilience trajectories between children were due to time-invariant factors.

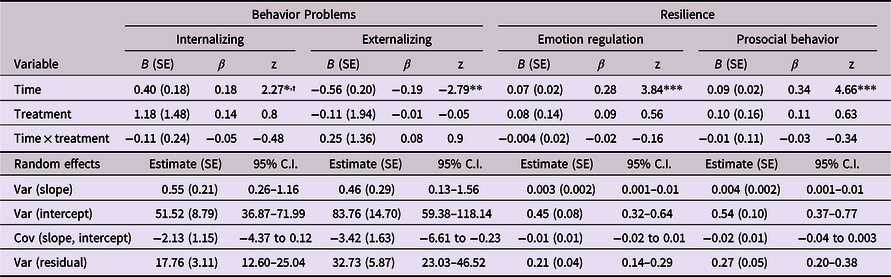

Research question 1: testing intervention effects on adjustment trajectories

Across all models, the time by treatment group interaction term was not significant, indicating that changes in behavior problem and resilience scores over the 8-year period did not differ based on group assignment (see Table 3). The random effects terms in the models provided information about interindividual difference in trajectories of behavior problems and resilience. Across all models, the variance in slopes was significant. Thus, there was significant heterogeneity in the rate of change in behavior problems and resilience across children. Moreover, the rho (ρ) term was significant for the externalizing behavior model (ρ = −3.42, p < .05). Children with higher baseline externalizing scores experienced less growth in externalizing over time than children who started at lower levels.Footnote 1 After applying the BH correction, the time coefficients for internalizing and externalizing scores no longer met the threshold for significance.

Table 3. Results of multilevel model testing the effects of intervention participation on behavior problem and resilience trajectories

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

† Not significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Post-hoc treatment analyses

A prior investigation of maternal mental health outcomes 6–8-months post-intervention demonstrated that mothers who attended at least eight (of 10) intervention sessions experienced significant reductions in PTSD (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Howell, Miller-Graff, Galano, Lilly and Grogan-Kaylor2019). We conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine dosage effects modeling the effects of time and number of sessions, and the interaction between the two. For the 68 families who received the intervention, average attendance was between 5–6 sessions (of 10; SD = 2.99). Thirty-five percent (n = 24) of families who received the intervention attended at least eight sessions. We found a trend-level effect for the interaction between time and number of sessions (B = −0.13, p = .062), indicating that greater intervention engagement was associated with an attenuated increase in internalizing problems. We also modeled the interaction between time and a session cutoff variable, grouping families into those who received at least eight intervention sessions versus those who did not. Children who attended at least eight sessions of the intervention experienced less increase in internalizing problems over time compared to children who did not receive that dose (β = −0.33, p = .003). We also found a trend-level effect for emotion regulation outcomes in relation to the eight-session cutoff. Children who received at least eight sessions of the intervention experienced greater gains in emotion regulation than children who did not receive that intervention dose (β = 0.20, p = .060). These results were retained after the BH procedure was applied to the calculated p-values.

Research question 2: factors inhibiting or supporting behavior problems and resilience

Additional models were analyzed to test factors outside of intervention participation that may affect behavior problem and resilience trajectories. Given that there were no significant differences in trajectories of adjustment across children in the intervention and control conditions, intervention assignment was not included these models. However, the dosage term was retained in the internalizing problems model, given that it was significant post-hoc treatment analyses. Child sex was included as a covariate in these models given baseline sex differences in the outcomes of interest.

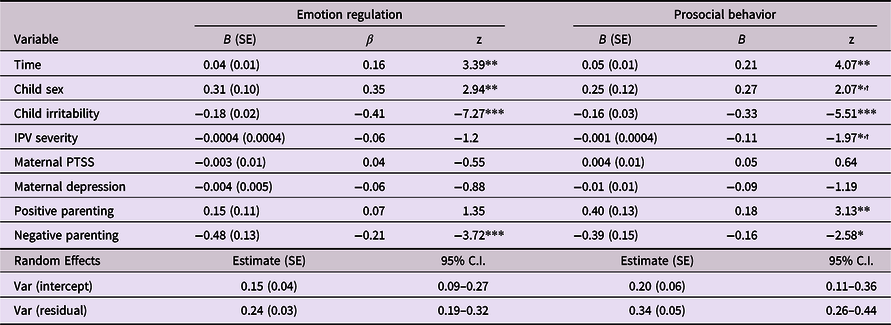

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation increased over time (β = 0.16, p < .01). Girls had significantly higher rates of emotion regulation skills over time (β = 0.35, p < .01). Greater irritability was associated with poorer emotion regulation (β = −0.41, p < .001). IPV exposure did not predict emotion regulation over time. Neither parental PTSD symptoms nor parental depression symptoms were significantly associated with emotion regulation trajectories. Maternal negative parenting was associated with poorer emotion regulation (β = −0.21, p < .001); however, positive parenting was not. Post-hoc analyses revealed that none of these significant predictors impacted the slope of emotion regulation. Thus, while these variables were associated with emotion regulation across time, they did not contribute to differences in the rate of change in emotion regulation. These results were retained after the BH procedure was applied to the calculated p-values (see Table 4).

Table 4. Multilevel models predicting resilience trajectories

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

† Not significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Prosocial behavior

Prosocial skills increased over time (β = 0.21, p < .01), and girls had higher levels of prosocial skills (β = 0.27, p < .05). Greater irritability predicted less prosocial behavior over time (β = −0.33, p < .001). Exposure to more severe IPV was related to fewer prosocial skills (β = −0.11, p < .05). Maternal mental health was not related to prosocial skills over time. Negative parenting was associated with fewer prosocial skills (β = −0.16, p < .05), while positive parenting was associated with greater prosocial skills (β = 0.18, p < .01). Post-hoc analyses revealed no significant effects of significant predictors on rate of change in prosocial behavior; however, after applying the BH procedure, sex and IPV exposure no longer met the threshold for significance. See Table 4 for full model results.

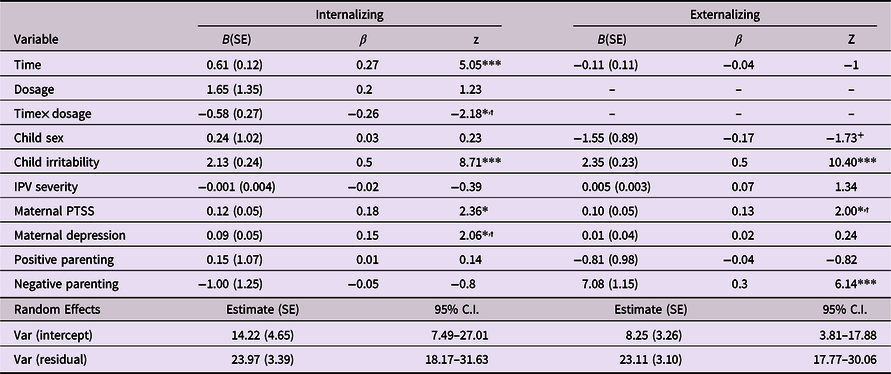

Internalizing problems

Children’s internalizing problems increased over time (β = 0.61, p < .01); however, child sex was not associated with internalizing over time. Greater irritability predicted more internalizing problems over time (β = 0.50, p < .001). IPV exposure was not significantly associated with internalizing problems over time. Higher maternal depression (β = 0.15, p < .01) and maternal PTSS (β = 0.18, p < .01) were both associated with greater internalizing across time. There were also no significant effects of maternal parenting behaviors on internalizing problems. Post-hoc analyses revealed that none of the significant predictors impacted the slope of internalizing problems. The effects of treatment dose and maternal depression no longer met the threshold for significance after applying the BH procedure (see Table 5).

Table 5. Multilevel models predicting behavior problems trajectories

**p < .01.

+ p < .10.

* p < .05.

*** p < .001.

† Not significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Externalizing problems

Time was not significantly associated with externalizing problems, suggesting that, after accounting for all covariates in the model, children’s externalizing problems were stable over time. Higher irritability predicted greater externalizing over time (β = 0.50, p < .001). IPV exposure had no relationship with externalizing outcomes over time. There was no relationship between maternal depression and externalizing problems, yet greater maternal PTSS were associated with higher externalizing across time (β = 0.13, p < .01). Negative parenting behavior also predicted higher externalizing problems (β = 0.30, p < .001), while there were no significant effects of positive parenting. Once again, post-hoc analyses tested the effects of significant predictors on the slope of externalizing trajectories; the rate of change in externalizing did not vary as a function of any of the significant predictors in the model. After applying the BH procedure, the p-values for maternal PTSS no longer met the threshold for significance.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine how several individual- and family-level factors – including early intervention– contributed to IPV-exposed children’s problem behavior and resilience trajectories over 8 years. Brief, early intervention did not have a significant effect on children’s adjustment, adaptive or maladaptive, over this time. However, children’s irritability, maternal mental health, and maternal parenting practices were all associated with child adjustment over time.

Intervention participation was not significantly associated with trajectories of adjustment. Although the intervention significantly reduced children’s internalizing problems and increased their resilience in the year following receipt of the intervention, this did not translate into long-term (measured across 8 years) improvements in functioning. Given that resilience increased over time across the entire sample, the lack of intervention outcomes may indicate that, with time, children in the control group caught up to children in the intervention group on resilient functioning. Access to positive peer and school supports may have contributed to increases in resilience outside of intervention participation, given that those factors have been associated with higher resilience (Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). Conversely, internalizing symptoms increased over time, regardless of intervention participation, although this was not significant across all models. Any number of other factors could contribute to this increase; however, it is clear that early intervention alone, especially one that was held for 5 weeks, did not necessarily promote lasting changes in well-being. One gap in current family-based intervention is the lack of integration of programs for survivors and their children with programs for perpetrators of the violence. More whole-family treatment could have greater short- and long-term effects, as this might address the root causes of the violence in addition to the problems stemming from it. Moreover, considering the effects we found at high doses of the intervention, developing strategies for increasing intervention engagement might also promote more long-term intervention effects. Another strategy for promoting long-term intervention benefits could be to incorporate technology to provide continued support and access to resources when the intervention ends, especially considering the positive concurrent and short-term effects of the intervention (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Stein and Graham-Bermann2021a; Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Miller-Graff, Howell and Grogan-Kaylor2015).

Shared factors across risk and resilience trajectories

Childhood irritability was uniformly associated with all outcomes. Greater irritability was associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems, and it was also associated with lower resilience over time. Our findings related to irritability and internalizing/externalizing further contribute evidence suggesting that irritability is a nonspecific risk factor for psychopathology in childhood (Brotman et al., Reference Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine and Leibenluft2017). We extend that work to suggest that this factor also undermines resilient functioning following IPV exposure. However, continued research is needed to examine how temperament relates to resilient outcomes, given prior findings that positive temperament is related to greater resilience (Martinez-Torteya et al., Reference Martinez-Torteya, Anne Bogat, Von Eye and Levendosky2009). Currently, irritability is not uniformly assessed in IPV-exposed children; however, these findings suggest that high levels of irritability should be recognized and addressed following IPV exposure, regardless of whether the goal is to reduce problem behavior or enhance resilience. Future work should examine the relationship between irritability and adjustment following other forms of trauma to see if this is a factor relevant for trauma-exposed children generally, or to only specific types of trauma exposure.

Maternal parenting − specifically negative parenting behavior − was the only other factor related to both behavior problems and resilience in this sample. Greater use of negative parenting strategies (e.g., corporal punishment) was associated with higher levels of externalizing problems and less resilience over time. This is consistent with prior work demonstrating that negative parenting, particularly in the context of adversity, is especially detrimental to child functioning (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Grogan-Kaylor, Galano, Stein and Graham-Bermann2021b; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Kim and Fisher2012; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Chan, McCarthy, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2018; Symes et al., Reference Symes, Mcfarlane, Fredland, Maddoux and Zhou2016). However, positive parenting behaviors were only associated with prosocial behaviors in this study. This is likely not explained by greater use of negative parenting practices compared to positive ones, as studies on parenting in the context of IPV have found that mothers report greater use of positive parenting strategies than negative ones (Grogan-Kaylor et al., Reference Grogan-Kaylor, Stein, Galano and Graham-Bermann2019b). Positive parenting has been conceptualized as an important buffering factor against the negative effects of adversity on child functioning (McLaughlin & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin and Lambert2017). Yet, these findings suggest that positive parenting may not be sufficient to counteract the negative effects associated with IPV, which is a pervasive form of adversity with detrimental effects on the entire family system.

Unshared factors across risk and resilience trajectories

Maternal mental health and maternal positive parenting demonstrated unique associations with behavior problems and resilience, respectively. Greater maternal PTSS were significantly associated with higher internalizing behaviors over time. Maternal PTSS was associated with externalizing behaviors and maternal depression was associated with internalizing behaviors; however, these associations were not significant after adjusting for multiple testing, suggesting that these relationships were more tenuous in our sample. No maternal mental health indices were related to emotion regulation or prosocial behavior. On the other hand, positive parenting strategies in mothers were associated with more prosocial behavior over time. Positive parenting was not significantly associated with internalizing or externalizing problems. These findings provide further evidence for the idea that child adjustment – broadly defined – is as much a relational process as it is individual (Galano et al., Reference Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Stein, Clark and Graham-Bermann2020; Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Young and Hankin2021; Lannert et al., Reference Lannert, Garcia, Smagur, Yalch, Levendosky, Bogat and Lonstein2014; Scheeringa & Zeanah, Reference Scheeringa and Zeanah2001), particularly following IPV, which has negative ramifications for the entire family system. Future work more closely examining family relationships and processes in this context could give insight into mechanisms that explain why maternal mental health, particularly PTSS, is a predictor of child mental health broadly, even after accounting for the effects of parenting. That work could inform intervention refinement and adaptation to better address the effects of IPV across the entire family system, which would likely prove beneficial for child adjustment.

Our findings around maternal mental health are especially interesting. In the context of IPV, it seems maternal PTSS have greater effects on child functioning than maternal depression. This is consistent with more recent evidence that has simultaneously examined PTSS and depression in caregivers (Galano et al., Reference Galano, Grogan-Kaylor, Clark, Stein and Graham-Bermann2019; Jouriles et al., Reference Jouriles, McFarlane, Vu, Maddoux, Rosenfield, Symes, Fredland and Paulson2018) and contributes to findings that maternal PTSS have both direct and indirect effects on child adjustment following IPV (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Chan, McCarthy, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2018; McFarlane et al., Reference McFarlane, Fredland, Symes, Zhou, Jouriles, Dutton and Greeley2017). Thus, there is increasing need to understand how maternal PTSS influence child adjustment. While there is evidence that negative parenting explains at least some of this relationship, it does not fully explain the relationship between maternal PTSS and child functioning (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Chan, McCarthy, Wakschlag and Briggs-Gowan2018). Future work examining the effects of maternal PTSS on parent-child relationships might give insight into why caregiver PTSS seem to have especially detrimental impacts on their children.

The severity of IPV to which children were exposed was not significantly associated with any outcomes of interest once we adjusted for multiple testing. This is consistent with prior work showing no significant associations between trauma characteristics and adjustment problems when other factors are considered (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009; Howell & Miller-Graff, Reference Howell and Miller-Graff2014). Yet it is consistent with prior findings demonstrating that exposure to more severe IPV undermines resilience (Graham-Bermann et al., Reference Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell and Girz2009; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Graham-Bermann, Czyz and Lilly2010). Together, these findings suggest that IPV severity has weaker direct associations with child outcomes once other relevant individual factors and those in the child’s social ecology are taken into account. Importantly, IPV has influences on these other factors, which reinforces the idea that the effects of IPV on children are largely driven by indirect processes.

While we did not have a question directly related to sex, we included it as a covariate in the analysis given sex differences in the outcomes of interest. Child sex was only significantly associated with internalizing behaviors over time. This adds to a set of already mixed findings on sex differences in adjustment following early adversity. However, considering that this captured the period between preschool and early adolescence, it is possible that stronger sex differences may have emerged if we included time points later is adolescence, considering links between puberty and adjustment (Alloy et al., Reference Alloy, Hamilton, Hamlat and Abramson2016; Negriff & Susman, Reference Negriff and Susman2011).

Limitations

Although this study adds to our understanding of the long-term effects of early-life IPV exposure, there are still some limitations to its design. First, we experienced high attrition between Times 1 and 2. This was a sample that experienced not just high rates of violence, but also had limited economic resources and high rates of housing instability. This meant that across both groups, many families changed phone numbers and/or addresses even within this relatively short period. Given the time frame (2006–2012) of the second data collection point, access to personal information via social media and other internet platforms was limited, especially in comparison to what was accessible for the Time 3 assessment (2015–2017). Future studies utilizing more advanced and purposeful tracking methods might see less attrition over a similar time frame (for examples see Clough et al., Reference Clough, Wagman, Rollins, Barnes, Connor-Smith, Holditch-Niolon, McDowell, Martinez-Bell, Bloom, Baker and Glass2011; Dichter et al., Reference Dichter, Sorrentino, Haywood, Tuepker, Newell, Cusack and True2019). We also had uneven time intervals between assessments, with a long gap between Times 2 and 3. A number of intervening events, such as transitions from elementary to middle school, and additional factors, including peer influences, may have had important effects on the outcomes of interest. Moreover, having only two follow-up assessments across the 8 years does not allow for the examination of transactional processes, which are likely important to consider.

We were also limited in this study as we only had a single reporter for all outcomes. This excludes other potentially important reporters, including the child and other adults like teachers, who can provide different insight into child functioning. Finally, we are limited by our sample characteristics. The relatively small sample sizes at the follow-ups mean that we may have not had the power to detect smaller effects. As such, these results should be considered preliminary and necessitate replication with larger sample sizes. Further, participants were drawn from both Southeast Michigan, US and Southern Ontario, Canada. Considering how different social systems and policies are between these regions, there may have been important environmental effects on the outcomes of interest that we were unable to examine given the small number of Canadian participants. Future work utilizing samples of equivalent size across geographical regions could provide greater insight into how the broader social ecology affects the adjustment of IPV-exposed youth.

Conclusions

Overall, these results suggest that increases in both behavior problems and resilience are observed following exposure to violence in early life. However, this particular brief intervention – even when effective in the short-term – did not confer long-term positive effects, suggesting the need for continued intervention and support for IPV-exposed children. This has important implications for psychoeducation and policy-making around violence intervention and prevention. Moreover, these findings point to several individual and maternal factors that may be future intervention targets to reduce adjustment problems and enhance resilience.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families who participated in this research, as well as the many research assistants who supported data collection over the years.

Funding statement

This research was supported by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

None.