Since the tragic events at Columbine High School in April 1999, the terms “active shooter” and “active shooter on campus” have become part of the language of law enforcement, public and private school systems, and the news media. Following the mass shooting at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) in April 2007, the term “active shooter” quickly became part of the dialogue on safety and security of the nation's colleges and universities. The broader discussion of campus security began in the wake of the terrorist assaults of September 11, 2001, when the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation referred to colleges and universities as soft, vulnerable targets to acts of terror.Reference Boynton1

The shooting tragedy at Virginia Tech, which led to the deaths of 33 people including the shooter, brought attention to a number of issues affecting safety and security on the nation's campuses. These issues are being debated on campuses and in law enforcement agencies, the media, and federal and state legislatures:

• Access to firearms on campus

• Prevention of gun violence on campus

• Gun control

• Availability of mental health services to college students

• Encouragement of students to take advantage of mental health services

• Release of information on at-risk students

• Public safety response to active shooter situations

• Reactions of students, faculty, and staff to an active shooter

This article focuses on the importance of preventing active shooters, as well as strategies for coping, common assumptions, dynamics, and various scenarios. It attempts to separate myth, fact, and hyperbole.

An active shooter is defined as an armed person who has used deadly force and continues to do so with unrestricted access to additional victims.2 It is important to distinguish an active shooter, as was present at Virginia Tech, from other criminal suspects who rely on firearms. Other types of shooters include those who enter campus to do harm to a specific person; those who react spontaneously to a fight, domestic argument, or other catalyst; and those who use a firearm to commit a crime such as robbery.

The issue of guns and other weapons on campus has been discussed for some time. A 2002 study suggested that as many as 4% of students have access to a firearm on campus.Reference Miller, Hememway and Wechsler3 Although deaths by shooting on college and university campuses are tragic and generally well publicized, the number over the past 40 years remains small.4 Media accounts tend to prejudge and stereotype lethal school violence.Reference Hagan, Hirschfield and Shedd5 In doing so, they overstate or imply a greater extent of threat than actually exists.

Addressing the potential of an active shooter on campus is a complex undertaking for college, university, and public safety officials. Officials must strike a balance between rhetoric, action, and exacerbating fear. To be effective, officials should adhere to 6 basic objectives. These objectives narrow the scope of actions to those that are essential to prevention and effective communications:

1. Make prevention a priority.

2. Develop preparedness and response strategies and tactics and publicize them, reminding all stakeholders that college and university campuses remain among the safest environments in any community, having among the lowest level of per capita crime reported by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.Reference Boynton1

3. Develop and implement policies and procedures that seek to achieve needed behavioral change, more so than for political, public relations, or liability purposes.

4. Implement analyses, policies, and programs relevant to the needs of and risks within the college or university, rather than simply adopting practices common to other institutions.

5. Reinforce the stability and safety of the campus environment, minimizing the sense of vulnerability and uncertainty often caused by discussion of active shooters.

6. Affix responsibility for action and follow-up on individuals and do not assume that Web sites, meetings, orientations sessions, and brochures will influence stakeholders.

PREVENTING ACTIVE SHOOTERS

The most important means for dealing with active shooters is prevention. Campus officials, as well as their colleagues serving K–12 schools, play an essential role in identifying potential shooters before they act. For prevention to be effective, however, these officials must overcome traditional obstacles such as denial, anxiety about negative affect on enrollment, apprehension over stereotyping or profiling, and concern about parental reaction. Faculty, staff, counselors, and campus police and security personnel are in the best position to identify and react to warning signs such as ambiguous messages in papers and student projects, direct threats, rumors about guns and other weapons on campus, victimization by social groups or individuals, mimicry of media figures, change in emotion or interests, isolation, repeated engagement in minor offenses or violations, and lack of family connection and support.Reference Twemlow, Fonagy and Sacco6

In facilitating prevention and preparedness, campus officials must establish a relationship with faculty and students based on trust and shared objectives. A trust-based relationship becomes the catalyst for the most effective prevention measures, and is the foundation of prevention and interdiction. Steps to cultivating and maintaining trust are as follows:

1. Build an environment in which students know where to go and whom to trust to share information about rumors, suspicions, and deviant behavior.

2. Reinforce a “no weapons” policy and, when violated, enforce it quickly, to include expulsion. Parents should be made aware of the policy. Officials should dispel the politically driven notion that armed students could eliminate an active shooter.

3. Educate and work closely with members of the faculty to improve their skills in dealing with disgruntled students.

4. Improve the quality of campus officials' interview skills to increase depth of inquiry. Education and training in interview techniques should be provided to all campus public safety personnel.

5. Consider public address (PA) systems in classrooms, dormitories, and exterior locations.

6. Focus on dormitory administrators and monitors.

7. Recognize the need to continuously maintain and cultivate critical relationships and communications strategies due to turnover among officials, faculty, students, and law enforcement.

Building trust requires more than simple information sharing. Repeated sessions with students, high visibility by key administrators, faculty involvement, student relationship with police and security personnel, and the involvement of special interest groups are paramount to building trust. Of the 15 major shootings on US college campuses cited by the Chronicle of Higher Education, as many as 6 may have been related to students who were concerned or angry about a failure or other academic problem.4

There are effective and low-cost ways to improve communication. PA systems provide a low-tech means of communicating in a crisis. Some allow for communication on a room-by-room or area basis, so that separate messages may be sent to students based on their location relevant to the shooter. In addition, dormitory administrators and monitors have the potential to be among the most effective observers of unusual behavior and often are among the first to hear rumors, speculation, and suspicions from students.

Most important is the recognition that turnover among administrators, faculty, and other key players and the enrollment of new students requires that education and involvement be an ongoing process. Police district, precinct, and barracks commanders also change rapidly. Orientation of local and state police to the needs of the campus is an ongoing process as well.

DISPELLING FALSE ASSUMPTIONS

Certain assumptions and misperceptions need to be dispelled to better guide and support students, faculty, staff, and others in dealing with active shooters:

• Awareness is readiness.

• Plans and advice to students, faculty, and others are clear and understood.

• Having a plan and/or policy and placing it on the campus Web site will affect people's (students, faculty, police, security, administrators) behavior in responding to a crisis.

• One-time training or orientation will affect people's behavior in responding to a crisis.

• First responders are near enough to engage the active shooter.

• Those with responsibility for overseeing an active shooter crisis have mastered the basic skills that are necessary to manage the situation.

There is a significant difference between awareness and readiness. Simply providing information to increase awareness of a problem and potential solutions does not ensure preparedness or appropriate response in a crisis.

Active shooter advice appearing on campus Web sites is often confusing and conflicting. It advises students to move away and take cover, be still and run away in a “zigzag” pattern, and never confront the shooter and fight. It suggests that students make noise, speak to the shooter, and be silent. It tells students to “act dead” and throw things to confuse the shooter, and hide behind a desk and brace against a wall. Situations vary and all of this advice could have merit. Nonetheless, the conflicting advice may inhibit recall in times of crisis.

Officials assume that students read Web-based information with interest and absorb the intended messages. The reality is that students are saturated with policies and procedures, promotional material, and educational materials. Means other than Web sites need to be considered to convey information and facilitate learning.

A single exposure to a how-to list, setting forth guidelines for dealing with an active shooter has little value in causing people to react in a desired way. Repetition, reinforcement, and varied approaches to conveying information are essential to ingraining more than superficial awareness. In addition to various means of delivery (Web-based, print, seminars, classroom discussion), engaging different constituents (faculty, security personnel, counselors, administrators, parents) in the information-sharing process, will connect with and have value for the broadest audience.

Rarely will first responders be near enough to mitigate the situation before the shooter ends the deed. The belief that a well-equipped, highly trained SWAT team or other special operations unit will arrive to intervene to end the crisis is a misperception. A timely, specialized response sufficient to stop the active shooter will occur in the rarest of cases.

Education and training for administrators and police and security personnel are lacking. Participation in a one-time seminar or a single tabletop exercise is awareness, but it does not ensure recall of tactics, coordination, communication, or adequate response to diverse situations. Campus leaders need to commit to an ongoing process of discussion and debate, education, risk analysis, and practice in dealing with major situations (active shooter and other types) to overcome standard shortcomings and facilitate mastery in crisis management.

REALIZING REALITY OCCURS IN SECONDS

Once an environment of trust and shared values is cultivated and maintained, and all of the relevant assumptions measured and addressed, there are certain realities about active shootings that must also be considered. Active shooting situations are quick, measured in seconds rather than minutes or hours.7 This negates much of the rhetoric and planning that focus on time-consuming tactics. In developing plans, policies, and educational programs, campus administrators should consider that active shooting situations, once they occur, will negate most time-reactive strategies. For example, time will preclude rapid intervention by police. Should it occur, police response in the early moments of the situation will involve an area patrol officer who will be the single first responder. The officer will quickly assess the situation and formulate deployment tactics.8 To do any less and simply rush into the situation is impractical. It could exacerbate the crisis and lead to unnecessary additional victims. Students, faculty, and others should not be given 10 minutes of survival techniques for a 25-second-long situation. Suggesting too many steps is fruitless. Focusing on a few concrete action steps has more value than a long list of suggestions. Suggesting that potential victims actively team with others to plan their exit, attack the shooter, or conduct other tasks is important, but unlikely to occur. The suddenness of the situation and the speed with which it occurs precludes organized response by victims. Despite the best efforts of campus officials, the human survival instinct will drive people's immediate reaction.

OVERGENERALIZING BASED ON PROFILING

Despite efforts to profile active shooters, there are more variances in situations that have occurred and differences in the shooters than there are similarities.Reference Verlinden, Hersen and Thomas9 In their eagerness to respond to the Virginia Tech incident, college, university, and law enforcement officials seek commonalities. Profiling involves identifying common characteristics. Much of the advice being given to students and others on how to react is based on profiling past campus shooters. This is problematic. First, there have been too few active shooting incidents on college campuses to draw significant conclusions about the perpetrators. Second (also due, in part, to the small number of incidents), there are no conclusive patterns to predict how future shooters will act. Situations have involved single shooters, multiple shooters, close encounters, distant encounters, targeted students, random victims, contained (single room) confrontations, and mobile confrontations. Suspects have spoken, remained silent, laughed, and remained solemn. Some had prior contact with their victims, others had none. Some shooters were considered oddities, whereas others seemed “normal.” The only certainty is that each situation will be different. As such, advice to students, faculty, and others must be kept in perspective.

There are common characteristics among past shooting situations, but they have little relevance to prevention and planning with regard to victims and shooters. It has been shown that the shootings do not involve motivational factors common to street shootings such as gang rivalries, illegal narcotics, or robbery. The shooters do not seek financial or other forms of personal gain. Most are young men from middle or upper-class families. Many have no criminal record.Reference Verlinden, Hersen and Thomas9

Concern about profiling active shooters and how they react was expressed in research conducted by the US Secret Service (USSS) and the US Department of Education. In its report on evaluating risk for targeted violence in schools, USSS officials noted that profiling is inadequate in predicting students likely to become “school shooters,” is fraught with inaccuracies, and carries considerable risk for false positives. A primary reason for concern about profiling incidents is the lack of incidents. For example, an offender profile developed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1999 was based on 6 school shooting incidents. The Bureau's study failed to compare its profile to more than 30 other identified school shootings that occurred in the United States in 20 years before the study.Reference Reddy, Borum and Berglund10

DIFFERENTIATING SHOOTER SCENARIOS

Active shooter situations tend to change quickly. First responders faced with an active shooter know that the situation will change, evolving into a dramatically different scenario, as in the following list of potential scenarios:

Mobile crisis: the shooter continues to fire but has chosen to do so while on the move

Fleeing suspect: the shooter has ceased the act and has fled the scene, but remains mobile in the immediate area

Suicide or suicide threat: the shooter ceases shooting others and threatens to take his or her own life or has done so

Homicide investigation: the shooting has ceased, the shooter has been captured or terminated, and the process of investigation begins

Trauma response: the shooting has ceased, the shooter has been captured or terminated, and a large number of injured people require attention

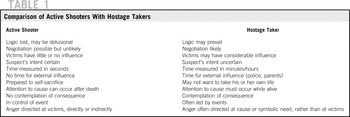

There are significant differences in response and potential for positive outcomes when an active shooter ceases firing his or her weapon. Although the opportunity to divert an active shooter during the act is slight, victims and public safety officials have significant influence on affecting the outcome when the situation becomes a hostage taking. To provide perspective on 2 different scenarios, Table 1 compares an active shooter to a hostage taker.

TABLE 1 Comparison of Active Shooters With Hostage Takers

NEGOTIATING IS IMPROBABLE

Negotiation, as suggested on many universities' Web sites as a possibility in dealing with an active shooter, is improbable while the act of aggression is occurring. Law enforcement officers are taught that hostage negotiation is contingent on 3 elements: opportunity and willingness to negotiate, containment, and time. If these 3 prerequisites exist, then negotiation is feasible and can succeed. In many crisis situations, such as the shootings at Columbine High School, the fundamentals for negotiation do not exist. Attempts to avoid additional violence by having victims talk to the assailant have a high risk for failure in an active shooter situation. During an active shooter situation, the perpetrator is in an acute state of stress that disrupts normal thought, reason, and functioning.Reference Noesner11 Should the situation evolve into a barricaded subject or hostage taking, in which the shooting has ceased, conversation and negotiation become much more feasible.Reference Klein12

CONCLUSIONS

There is a great deal of information being disseminated on campuses about active shooters and how to deal with them before and during the commission of the assault. College and university officials base this information in part on profiles and stereotypes drawn from a small number of incidents that have taken place on college and university campuses during the past 4 decades. Assumptions have thus been made about how shooters and victims act during the crisis, and many of these assumptions are false.

Prevention remains the best first step to be taken. Some of the most important preventive steps, such as prohibiting guns on campus and sharing information about mentally and emotionally ill students, will be debated for years.

Keeping perspective is paramount. The number of active shooter situations and mass murders on college campuses in the United States is small. Campuses remain among the safest places to be in any community. The incident at Virginia Tech has not changed this fact. Focus on more prevalent campus concerns such as alcohol abuse, suicide, sexual assault, off-campus activity, ingress and egress at odd hours, and intrusion from the external community should remain the priority.

Advice to students will have little effect if not reinforced. Simply placing information on a college or university Web site is ineffective. Students, faculty, staff, parents, and other stakeholders need to meet and hear from leaders who must create a sense of trust, overcome media hype by putting the potential for the occurrence of an active shooter situation in perspective, and manage fear. Reinforcing how to cope with an active shooter is important because, generally, first responders will not arrive in time to stop the assault.

Perhaps the best advice comes from George Mason University's chief of police Michael Lynch. He suggests several simple but highly effective core concepts to students: “Act smart, make good decisions, take care of each other, and take care of yourselves.”