Since 2010, there have been more than 250 disasters in the United States, impacting over 88 million people. 1 Such disasters result in the need for sheltering for thousands of people. In 2017, there were 226,903 shelter stays and in 2018, there were 884,513. 2 The American Red Cross (ARC) co-leads sheltering efforts in the United States in partnership with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), providing care to individuals affected by disasters with subsequent sheltering needs. 3 Clients’ time spent in such shelters ranges from days to weeks. Reference Peacock, Dash, Zhang, Rodríguez, Donner and Trainor4

Shelters assist people impacted by disasters, including those who have evacuated. In addition to basic supports, including food, water, and a sleeping area, services for health-care and mental health support, or referrals for these, should also be provided. 2,Reference Phillips, Wikle and Hakim5,6 While federal agencies and organizational guidelines direct what a shelter will provide (eg, FEMA, 2015), 7 few details are known about the provision of specific care and supportive services for shelter clients in past disasters. Some who depend on shelters have fewer resources and lower socio-economic status, or their homes were in disrepair before the disaster. Reference Peacock, Dash, Zhang, Rodríguez, Donner and Trainor4,Reference Phillips, Wikle and Hakim5 People with greater financial and social capital resources are more likely to shelter with friends or family or in hotels. Reference Morrow, Peacock, Morrow and Gladwin8,Reference Whitehead, Edwards and Van Willigen9 Potentially compounding the provision of care and supportive services in shelters, people with lower socio-economic status experience a greater burden of disease than those with higher income levels. 10 Considered together, these factors may contribute to significant health-care and support needs within shelters.

An analysis of client needs within shelters can aid planners in preparing staffing and other required resources, yet currently, there is limited literature on shelter needs for physical and mental health support. In fact, a 2015 review revealed a “tremendous need exists to…describe the care that is being provided in disaster shelters both in the United States and internationally.” Reference Veenema, Rains and Casey-Lockyer11(p230) Studies have addressed health care provided to shelter clients in settings such as mega shelters, Reference Faul, Weller and Jones12 medical special needs shelters, Reference Missildine, Varnell and Williams13 makeshift shelter clinics, and aid stations. Reference Caillouet, Paul and Sabatier14 Medical special needs shelters are “designed to meet the needs of persons who require assistance that exceeds services provided at a general population shelter.” 15 The findings for these care settings may not reflect care provided in a general population shelter, that is, a shelter not designated as a special medical needs shelter. 15

Three studies in the literature have described the needs addressed in visits to ARC Disaster Health Services (DHS) in shelters. Reference Noe, Schnall and Wolkin16–Reference Schnall, Hanchey and Nakata18 A review of data from shelters and other ARC field service locations (eg, hospitals, service centers) across 39 counties impacted by Hurricanes Gustav and Ike revealed that 52% of visits to DHS were for acute illnesses and symptoms, 16% for routine follow-up care, 14% for chronic disease, 14% for injury, and 5% for mental health. Reference Noe, Schnall and Wolkin16 An analysis of shelter data from over 30,000 medical visits across 8 states after Hurricane Katrina characterized visits as acute, preventive/chronic, or both. Reference Jenkins, McCarthy and Kelen17 Another study analyzed ARC’s Aggregate Morbidity Report (tally format) Form for 24 shelters in Texas after Hurricane Harvey. Reference Schnall, Hanchey and Nakata18 Of the over 9000 client visits represented on the forms, 5621 were health-related. Many of these visits were acute, requiring referrals to physicians, dentists, hospitals, or clinics. Detailed analyses of the provision of care and other supportive services for clients within a general population shelter itself were not within the scope of these studies.

In 2007, the Communication (C), Medical Needs (M), Maintaining Functional Independence (I), Supervision (S) and Transportation (T) framework was introduced to better identify functional needs in an emergency response. Reference Kailes and Enders19 The ARC DHS later adopted this C-MIST framework, updating the dimensions to Communication (C), Maintaining Health (M), Independence (I), Services, Support and Self-Determination (S) and Transportation (T). Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 It is used as a philosophical framework intended to facilitate discourse between the client and shelter staff so the client can identify needs they might have, and shelter staff might observe the client for needs that may not be obvious. The ARC implements the C-MIST framework in conjunction with a registered nurse led model of care using a Cot-to-Cot process. Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 The Cot-to-Cot process involves making daily rounds with shelter clients to build relationships, establish trust, and gather data on the health and well-being of shelter clients. As part of the Cot-to-Cot process, C-MIST concepts are integrated into interactions with clients for as long as the client remains in the shelter, beginning with an initial C-MIST interview that is completed for each client household within 48 hours of their registration in a shelter. Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 A C-MIST documentation tool provides interviewers with a set of potential client needs. For any client needs indicated, the documentation tool also provides interviewers with a suggested list of ideas to consider meeting those needs; these are referred to as actions. A copy of this tool is included in the appendix.

Information contained in completed C-MIST documentation tools (ie, records), can lend insight into which health and other supportive needs have been documented for general population shelter clients, addressing the gap in the literature regarding care being provided in shelters. We are aware of 2 published studies that have addressed C-MIST data. In their Aggregate Morbidity Report Form data analysis, researchers noted that 1 area of the form is used to tally overall counts of C-MIST needs across its 5 dimensions. Reference Schnall, Hanchey and Nakata18 However, these counts were not included in the data presented and analyzed in the study. Another study described a pilot test of the C-MIST for ARC. Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 Aggregate data regarding the total number of needs indicated in reviewed records and how those were distributed across C-MIST dimensions were presented; however, a detailed analysis of disaggregated data was out of the scope of the pilot test. Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 Thus, the need remains for analysis of disaggregated C-MIST data to provide more insight into the care and support services provided in a general population shelter.

As a first step in addressing this gap, the purpose of this research is to describe the incidence of C-MIST needs and actions arising within general population shelters during and following hurricane and flooding events. The research accomplishes this goal by means of retrospective review of C-MIST records corresponding to general population shelter stays associated with Hurricane Florence in 2018. Two research questions (RQ) are explored:

RQ1: For what percentage of records is each C-MIST need and action indicated? (we refer to this as incidence).

RQ2: How many C-MIST needs and actions are indicated in each record?

Both are descriptive questions, for which statistics are computed from de-identified data abstracted from hardcopy C-MIST records.

Methods

A sample of 1248 C-MIST records corresponding to shelter stays in North Carolina for Hurricane Florence and associated flooding events (GLIDE number 2018-000420) were analyzed. The records were provided by ARC in hardcopy form. The sample consisted of records from 19 shelters; some in which the disaster health services personnel completing the records were managed by ARC and some in which they were managed by another entity. After abstracting the data using the methods described below, hardcopy forms were scanned and saved electronically to a secure server and returned to ARC.

A data dictionary was created to link each field in the C-MIST documentation tool to a variable. Additional variables were introduced to capture any text written on a record not specifically linked to a C-MIST field, such as text written in a page margin. Most of the C-MIST fields were checkboxes and were represented as binary variables (checked = yes = 1; not checked = no = 0). The remaining fields were either text string, numeric, or date. To protect confidential information, fields that contained identifying information were replaced with de-identified descriptive text.

Abstracted data were recorded in an SPSS database using a standardized abstraction form, where each row corresponded to a record, and each column corresponded to a data dictionary variable. Any field missing from a record was indicated in the database with an entry of “99” in the appropriate variable. This situation occurred, for example, when a record, typically a 2-page document, was missing its second page. Also, in some cases, a record missed some need fields or action fields or both, indicating an alternative version of the C-MIST documentation tool was in circulation during these shelter stays.

A handout with variable names overlaid on a blank copy of the C-MIST documentation tool was created to facilitate the correct transcription of data. It included written instructions, such as specifying that recorded data would be 0 (no) or 1 (yes) unless otherwise indicated. A research member provided a hardcopy handout to the data abstractors and trained them to use it and the database correctly. The data abstraction occurred in person over 5 days, with a total of 7 data abstractors participating. All abstractors were Graduate Research Assistants in a Nursing PhD program. One member of the research team supervised the work at all times. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability were not explicitly examined by means of a statistic such as Cohen’s Kappa, as the variables recorded (ie, a box is checked, not checked, or is missing from the form) were not nominal nor subject to interviewer judgment. Reference Cohen21

Of the 1248 records in the sample, those corresponding to shelter stays in North Carolina during September and October 2018 met the criteria for inclusion in the study. These criteria were assessed by examining the shelter location and date fields. One shelter location was discovered for which all 26 records had dates outside the inclusion period, so these records were excluded. The hardcopy forms were inspected for other records with dates outside the inclusion period to determine whether data entry errors had occurred when populating the date field in the database. If the date field entry on the hardcopy met inclusion criteria but differed from the electronic record, the electronic record was corrected. If the date field entry on the hardcopy did not meet inclusion criteria, the credibility of the handwritten date was assessed by comparing it with other records sharing the same shelter location and interviewer. If the hardcopy showed inconsistencies in all 3 fields (date, location, interviewer), the corresponding record was excluded from the analysis; otherwise, the record was retained. This verification process resulted in the removal of 13 additional records. The final database used in the analysis contained 1209 records from 19 shelters.

Research question 1 (RQ1) is a descriptive question regarding the incidence of needs and supportive actions in domestic general population shelters. For each need and action field on the C-MIST documentation tool, the proportion of records with this field checked (yes = 1) was reported. The variables n j and a k were used to denote the proportion of records with need j and action k checked, respectively.

Research question 2 (RQ2) is also a descriptive question, identifying the number of needs and actions checked per record. Distributions for these 2 measures were computed by C-MIST dimension and across the entire form. Specifically, G l and H l were assigned as random variables indicating the number of needs (G l ) and actions (H l ) in dimension l that were indicated in a single record, where the dimensions include l ∈ {C,M,I,S,T,all}. Here “all” refers to the entire record, inclusive of the other 5 dimensions. The distributions of G l and H l were reported. For example, suppose the range of G C is from 0 to 2, such that across all records reviewed, the minimum and maximum numbers of needs indicated in dimension C for 1 individual record are 0 and 2, respectively. Then, the distribution for G C reported the percentage of records indicating 0, 1, and 2 needs in the C dimension.

This study was conducted with an Institutional Review Board approval (protocol UMCIRB 20-000941).

Results

Research question 1 (RQ1) is addressed in Tables 1 through 4. First, in Table 1, the incidence of each need across all records is provided. There were slight variations in the C-MIST documentation tools in circulation in 2018, such that some needs and actions did not appear on all printed worksheets. Specifically, needs j∈{15,16,…,23} were printed on 1160 records, needs j∈{12,13,14} were printed on 1174 records, and all other needs were printed on all 1209 records. The highest incidence need was for medical supplies or equipment or both for everyday care (including medications) not related to mobility, with an incidence of 15.4%. The next 2 highest incidence needs were durable medical equipment (DME) for individuals with conditions that affect mobility (9.7%) and mental health care (eg, anxiety and stress management) (8.8%). The incidences of special diet and food allergies were 7.9% and 5.4%, respectively; combining these 2 needs yields an incidence of 12.2% of records indicating a need for a medically or culturally tailored diet. The incidences of transportation for medical care and transportation for a non-medical appointment were 6.4% and 3.3%, respectively; combining these 2 needs yields an incidence of 8.4% of records indicating a need for some type of transportation. Examples of needs with relatively lower incidence included service animal accommodations, infant supplies or equipment or both, and child personal assistance services, each with an incidence of 0.9%.

Table 1. Incidence of C-MIST needs

Table 2 provides summary information regarding need incidence across the 5 C-MIST dimensions. The first column provides the mapping of needs to C-MIST dimensions. The second column provides the incidence of records having at least 1 need in a C-MIST dimension indicated. Taking dimension C as an example, it contains the first 3 needs (j = 1,2,3), and 4.7% of records indicated at least 1, and possibly more, of these 3 needs. As another example, dimension M contains 11 needs (j = 4,…,14), and 37.1% of records indicated at least 1 of these. The dimensions with the highest incidence were Maintaining Health and Independence (37.1% and 13.7%).

Table 2. Summary of needs across C-MIST categories

Table 2 also indicates the total needs indicated in each C-MIST dimension (column 3) and the percent of total indicated needs attributed to each dimension (column 4). The dimension with the highest percentage of needs indicated was Maintaining Health, representing 60.7% of all needs indicated. Note that these 661 needs do not correspond to 661 distinct records, as more than 1 need was often indicated on a specific record.

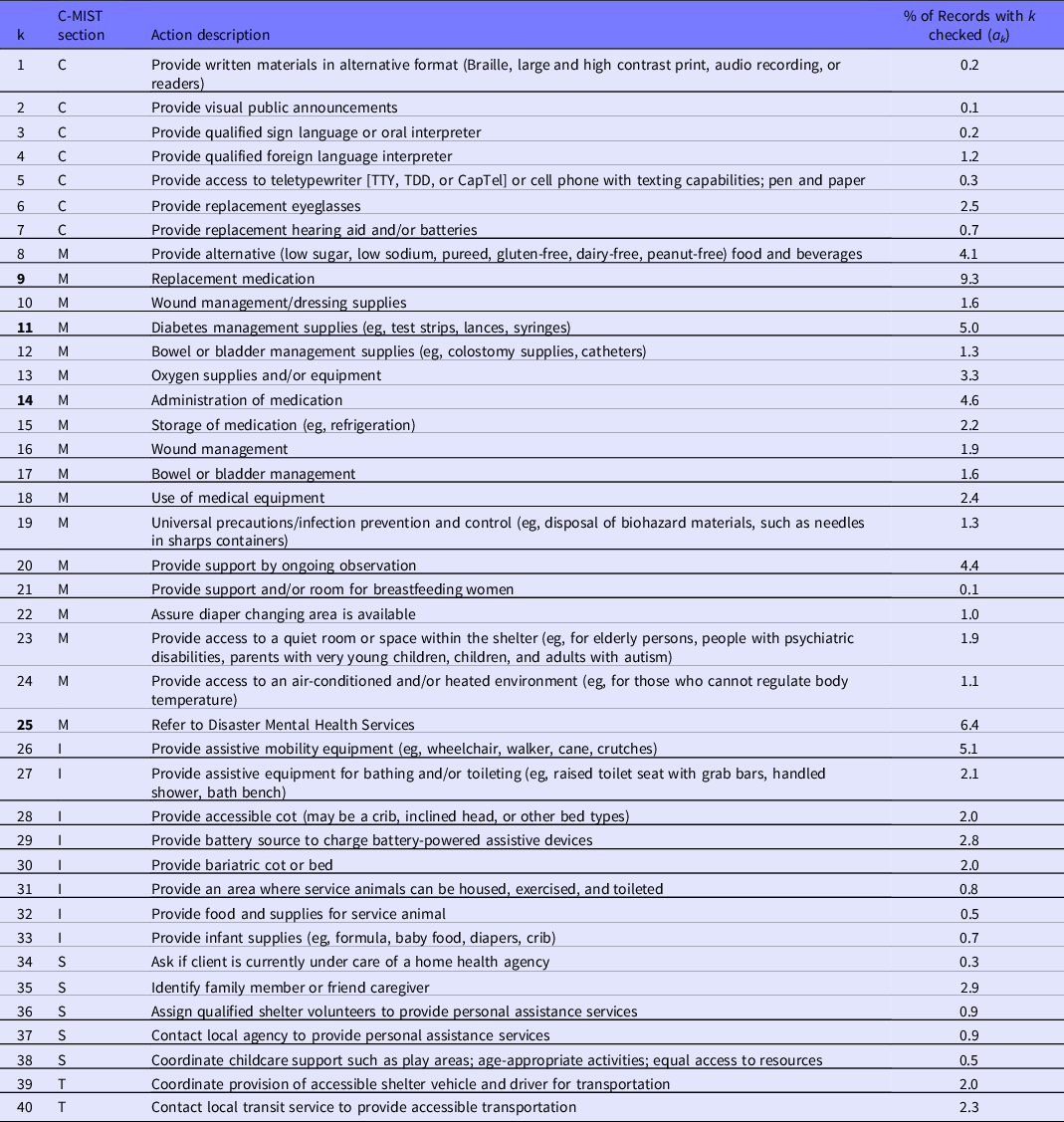

Table 3 provides the incidence of each action across all records. Action k=34 was printed on 587 records, actions k∈{27-33;35-40} were printed on 1160 records, actions k∈{23,24,25} were printed on 1174 records, and all other actions were printed on all 1209 records. The highest incidence action was for replacement medication, with an incidence of 9.3%. Other actions with incidences of 5% or higher include refer to Disaster Mental Health Services (6.4%), provide assistive mobility equipment (5.1%), and provide diabetes management supplies (5.0%). These high-incidence actions line up with the high-incidence needs. For example, the highest incidence need was for medical supplies for everyday care, including medications (15.4%); the highest incidence action was for replacement medication (9.3%). The next most frequent needs were DME (9.7%) and mental health care (8.8%), lining up with the provision of assistive mobility equipment (5.1%) and referrals to Disaster Mental Health Services (6.4%), respectively. Special diet and transportation were both frequently indicated as needs and appeared with relatively high incidences in corresponding actions as well, with the provision of alternative food and beverages indicated in 4.1% of records, and provision of accessible shelter vehicle and local transit service indicated in 2.0% and 2.3% of records, respectively. The incidence of records indicating at least 1 of the 2 transportation-related actions was 3.9%.

Table 3. Incidence of C-MIST actions

Table 4 provides summary information regarding action incidence across the 5 C-MIST dimensions. The first column provides the mapping of actions to C-MIST dimensions. The second column provides the incidence of records having at least 1 action in the dimension indicated. Taking dimension C as an example, it contains actions k = 1,…,7, and 4.8% of records indicated at least 1 of these. As another example, dimension M contains actions k = 8,…,25, and 32.3% of records indicated at least 1 of these 18 actions. As with indicated needs, the dimensions with the highest incidence actions were Maintaining Health and Independence (32.3% and 10.6%).

Table 4. Summary of actions across C-MIST categories

Table 4 indicates the total number of actions indicated in each C-MIST dimension (column 3) and the percent of total indicated actions attributed to each dimension (column 4). The dimension with the highest percentage of actions indicated was Maintaining Health, representing 63.9% of all actions indicated.

Research question 2 (RQ2) is addressed in Figures 1 and 2. The distribution of the number of needs per record for each C-MIST dimension is provided in Figure 1. Just over half of the records indicated no needs overall (53%), and just under half (47%) indicated at least 1 need (see G all ). Approximately 25%, 12%, and 4% of records indicated 1, 2, and 3 needs, respectively, with 4% that indicated 4 or more needs overall. Considering individual dimensions, over 90% of records indicated no needs in dimensions C, S, and T. In these same dimensions, a very small percentage of records indicated 1 need, at 4%, 5%, and 6%, respectively. Approximately 86% of records indicated no needs in the I dimension, with 12% of records indicating 1 need. Dimension M needs arose more often. While 63% of records indicated no needs in the M dimension, 25%, 8%, and 3% indicated 1, 2, and 3 needs, respectively. Only 1% of records indicated more than 3 needs in the M dimension.

Figure 1. Number of needs indicated per record.

Figure 2. Number of actions indicated per record.

Figure 2 provides the distribution of the number of actions per record for each C-MIST dimension. Approximately 60% of the records indicated no actions overall, 22% indicated 1, 8% indicated 2, and 9% indicated 3 or more actions overall (see H all ). Considering the individual dimensions, similar to the need distributions, over 90% of the records indicated no actions in dimensions C, S, and T. In these same dimensions, a very small percentage of records indicated 1 action, at 4%, 4%, and 3%, respectively. Approximately 89% of records indicated no actions in the I dimension, with 7% of records indicating 1 action. Dimension M actions arose more often. While 69% of records indicated no actions in the M dimension, 21%, 6%, and 2% indicated 1, 2, and 3 actions, respectively. Approximately 3% of records indicated more than 3 actions in the M dimension.

Limitations

A primary limitation of this study is that variations in training in the use of the C-MIST, norms in its administration, and level of its completion may introduce bias into the data. The research team perceived what appeared to be differences in percent completion and quality of completion between some of the records in the sample. This is similar to findings by Caillouet et al., Reference Caillouet, Paul and Sabatier14 regarding the completion of health-care encounter records, although these researchers collected data in medical needs shelters, whereas data for this study were collected in general population shelters. For example, some records in our sample had no marks on the second page of the C-MIST (a 2-page document). Some records included handwritten notes in the margin of the page, indicating a referral the client needed for a particular support service (eg, medical supplies needed). In some cases, corresponding items of the C-MIST did not appear to agree. For example, a record may indicate a need for a special diet or food allergies without specifying the indicated action of providing alternative food and beverages. While these anomalies can be explained (perhaps the clients brought their own alternative foods, or the interviewer took action on providing alternative food and beverages without indicating it on the record, or the action was recorded on the client health record instead of the C-MIST), they can affect summative needs and actions reported. One suggestion to address these inconsistencies is to implement just-in-time training on the C-MIST framework and interview process that can be accessed when nurses are deployed to a general population shelter.

A limitation of these findings is they are based on a single incident (a hurricane and associated flooding) in a specific location (North Carolina) in the United States. Trends in needs resulting from displacement due to other disaster types may be different. Furthermore, variations in health disparities observed throughout the United States may lead to different findings in different places (eg, different states). However, these limitations are tempered by our authors’ perspectives that the findings are reflective of their common experience in shelters after various incident type in various places throughout the United States.

Discussion

This study is the first retrospective analysis of C-MIST records since its pilot test Reference Springer and Casey-Lockyer20 of which we are aware. The 1209 records reviewed correspond to general population shelter stays in North Carolina during Hurricane Florence and the associated flooding events during September and October 2018. Through a review of these records, this manuscript reports the observed incidences of needs and indicated actions recorded on the C-MIST. The highest incidence needs include medical supplies for everyday care (including medications), DME, mental health care, and special diet and food allergies. The highest incidence actions align somewhat with these needs: provide replacement medication, refer to Disaster Mental Health Services, and provide assistive mobility equipment.

This manuscript also reports the number of C-MIST needs and indicated actions per shelter client or client group. Overall, approximately half (53%) of the records indicate no needs, one-quarter (25%) indicate 1 need, and the remaining one-quarter (22%) indicate between 2 and 10 needs. For actions, 60% of the records indicate no actions, 22% indicate 1 action, and the remaining 18% indicate between 2 and 11 actions.

Maintaining Health is the dimension with the most frequently indicated actions and needs. It also lists a larger number of needs and actions than other dimensions. In dimension M, there are 11 needs and 18 actions, compared with 3 needs and 7 actions in C, 5 needs and 8 actions in I, 2 needs and 5 actions in S, and 2 needs and 2 actions in T. Some of the increased incidences in needs and actions in dimension M compared with other dimensions are explained by the relatively high numbers of needs and actions listed. Other differences are explained by the high incidences of some individual needs and actions listed in Maintaining Health. Of the 5 needs with the highest incidence, 3 are from M (j = 4, 6, and 14). Of the 5 actions with the highest incidence, 4 are from M (actions k = 9, 11, 14, and 25). The high incidence of these dimension M needs and actions suggests that shelter managers may be able to reasonably expect to encounter and address those needs in shelters.

Although dimension M contains the highest incidences of needs and actions, the importance of other dimensions should not be dismissed, particularly considering the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s document titled Guidance on Planning for Integration of Functional Needs Support Services in General Population Shelters. 22 This document guides the provision of Functional Needs Support Services (FNSS), defined as “services that enable individuals to maintain their independence in a general population shelter.” 22(pReference Morrow, Peacock, Morrow and Gladwin8) These services include reasonable modification to policies, practices, and procedures, access to DME (covered in dimension I), consumable medical supplies (dimension M), personal assistance services (dimension S), and other goods and services as needed. Thus, dimensions C, I, S, and T address FNSS to support residents with varying needs, conditions, and abilities to function independently within general population shelters. Such assistance might be provided by a nurse or unlicensed assistive personnel within the shelter. Regardless, planners stand to benefit from more in-depth knowledge of access and functional needs presented in a shelter to align services better provided with the skill levels required to address them.

This research provides foundational empirical data regarding access and functional needs presented in a shelter. This information could help inform the development of a shelter-client needs index or a shelter-staffing matrix, or both, although this possibility was not within the scope of this research. The use of acuity indices has been linked to patient outcomes in the acute-care environment. Reference AI-Dweik and Ahmad23 Complexity of support needs have been identified as important considerations in general population shelters after a disaster. Reference Veenema, Rains and Casey-Lockyer11 There is not yet enough empiric data regarding the health and functional support needs within a general population shelter to standardize practices and services within the shelter environment, although the process for identifying health and functional support needs could be standardized through the use of the C-MIST framework.

This research pertains to shelter practices in the United States. While each country has a disaster response framework and associated shelter practices, they are each unique and do not necessarily compare to one another. The C-MIST is a philosophical framework intended to facilitate discourse between the client and shelter staff so that the client can identify the needs they might have, and the shelter staff might observe the client for needs that may not be obvious. The C-MIST framework could be adopted by any country, despite the disaster response framework they use.

Several opportunities exist to extend this analysis in future work. Segmenting the records by shelter would allow for comparisons across shelters, for example, to determine whether significant differences in incidences of needs and indicated actions are observed between pairs of shelters. If observed, differences could point to differences in the clients’ health between shelters or how the C-MIST was applied between shelters. Collecting and analyzing additional C-MIST records from other disaster events would allow for these types of comparisons across events and hazard types. Comparing the incidence of C-MIST needs and indicated actions within shelters to the incidence of disease in the population surrounding the shelter could lead to predictive models to estimate what needs may present in a shelter, given the disease burden in the area. However, currently, there is no clear mapping between C-MIST items and specific disease burden variables publicly available at a small spatial scale to enable these comparisons. Finally, although this research is a beginning in the efforts to document and accurately describe services and health care rendered in shelter environments, future work should endeavor to more accurately document health-care and other services being rendered and the intensity of such services and ultimately link them to outcomes. Reference Veenema, Rains and Casey-Lockyer11

Conclusions

Of the C-MIST dimensions, Maintaining Health (M) is predominant. Of the 5 needs with highest incidence, 3 are from Maintaining Health (special diet; medical supplies and/or equipment for everyday care including medications; mental health care). Of the 5 actions with highest incidence, 4 are from Maintaining Health (replacement medication; diabetes management supplies; administration of medication; refer to Disaster Mental Health Services). Because of the predominance of Maintaining Health, we recommend that licensed health-care providers trained in use of the C-MIST framework be prioritized for staffing all general population shelters; both those managed by the ARC and by other organizations. Following this staffing recommendation for at least the first 3 wk of a disaster response supports the comprehensive identification of both functional and medical needs for shelter clients and the development of plans to address them.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

None.