Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes are global burdens and threats that pose major public health challenges to all nations. As populations become increasingly older, the effects of NCDs for humans and human societies are expected to worsen increasingly. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), the total annual number of deaths from NCDs will increase from 38 million (68%) in 2012 to 55 million by 2030. 1 - Reference Dye 4

Regarding large-scale natural disasters, people living in affected areas are typically forced to make drastic life changes because of scarce water and regular food supplies, relocation to other residences such as evacuation centers and temporary housing with poor living environments, loss of a family or job, and extreme mental stress associated with such conditions. In addition to these difficult circumstances, disaster-affected people with NCDs experience interruption of regular medical treatment attributable to loss of medicines and damage to hospitals. Such situations worsen their physical and mental condition. 5 - Reference Jhung, Shehab and Rohr-Allegrini 7 Therefore, people with NCDs are particularly vulnerable after a disaster.

With respect to large-scale disasters, NCDs are expected to pose important health problems because direct deaths and injuries from hazards might be reduced by the development of anti-hazard measures such as quake-resistant buildings and early warning systems. Clarifying the circumstances and issues of patients with NCDs involved in large-scale disasters and developing strong measures to minimize their physical and mental damage are extremely important for preparedness.

The Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) and the consequent massive tsunami on 11 March 2011, which created an extremely destructive disaster of historic and global note, left over 18,000 dead and missing in its wake. 8 In addition, many disaster-affected people were forced to move immediately to other residences because of extreme structural damage to their own residence: more than 400,000 residences were completely or partially destroyed or rendered uninhabitable by the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant accident. Regarding health care facilities, of 380 hospitals in 3 prefectures where the disaster damage was the most extreme, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefecture, 10 hospitals were destroyed completely; 205 hospitals restricted outpatient care immediately after the disaster. 9 , 10 Even after 1 month, 42 hospitals continued to restrict outpatients. 10 Regarding medical clinics aside from dental clinics, 83 of 4036 clinics were destroyed completely. 9 These circumstances made it difficult for disaster-affected residents of the region to receive adequate medical care from the acute phase through the chronic phase of the GEJE.

The issues and the circumstances experienced by GEJE-affected people with NCDs have not been clarified. Therefore, we systematically reviewed articles related to NCDs after the GEJE to clarify circumstances related to the disaster and to develop strong countermeasures to minimize physical and mental damage from future disasters.

METHODS

Research Plan and Registration

This was a systematic literature review based on the PRISMA statement, but it did not meet the inclusion criteria of the systematic review database (PROSPERO; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/about.php?about=inclusioncriteria). No meta-analysis was performed.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

An article was included in this review if all of the following were applicable:

1. The abstract was written in English. The text was written in English or Japanese.

2. The article described the number of patients with NCDs or their condition at the time of the GEJE, including those that existed before the earthquake and those that developed after the earthquake.

Exclusion Criteria

An article was excluded from this review if any of the following was applicable:

1. It described only infectious diseases or injuries.

2. It included only data from clinical trials.

3. It described direct physical effects of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant accident.

Information Sources

We reviewed articles available in the PubMed database (National Library of Medicine) related to NCDs at the GEJE published from March 11, 2011, through December 15, 2016.

Search

Databases were searched by using the search term “East Japan Earthquake.” We selected relevant articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in order of the title, abstract, and text.

Study Selection

The WHO states that NCDs, also known as chronic diseases, are not transmitted from person to person. 3 In addition to the 4 main types of NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes), other types of diseases such as renal diseases, allergies, and mental disorders are included among NCDs. For the present review, we defined NCDs as all diseases and disorders other than injuries and infectious diseases based on the Brazzaville Declaration. 11 To the present review, we added reports of studies that examined only changes in metabolic indexes such as an increase of body mass index (BMI), weight, and LDL cholesterol.

Result Integration

We selected key issues of NCDs after the GEJE for both common difficulties and disease-specific problems. Although various definitions of each phase might be made, we defined them as follows: acute phase, a few days immediately after the disaster; subacute phase, a period of 2 or 3 weeks after the acute phase; and chronic phase, several months or years after the subacute phase.

Risk of Bias About the Overall Study

For some types of NCDs, reports were scarce, with only one or no reports published at all. Therefore, the number of articles did not reflect the number of patients or the severity of their circumstances. Consequently, the present review of NCDs had limitations and biases related to the scarcity of reports. To date, no database exists of medical records related to the GEJE. No such database is available for use at medical sites such as hospitals, clinics, first aid stations, and evacuation centers. During and after large-scale disasters such as the GEJE, many different medical teams used their own forms and descriptive contents. Furthermore, the management of disaster-related medical records is not yet regulated by law. The differences and various management methods of the medical records complicated analyses of the number and states of patients after the disaster, including analyses of NCDs. 12

RESULTS

Study Selection

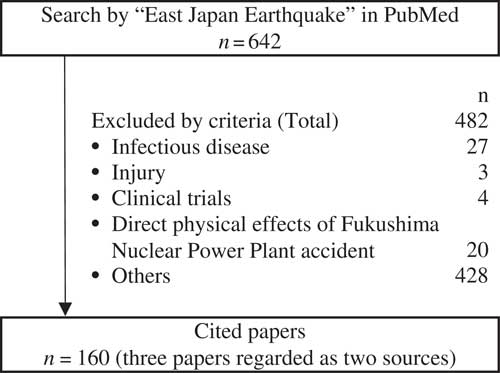

Searching PubMed by using the search term “East Japan Earthquake” identified 642 articles. Of those, 482 articles were rejected on the basis of the exclusion criteria. Consequently, we included 160 articles in the corpus of the present literature review (Figure 1). Of 160 cited articles, 142 articles were written in English and 18 articles were written in Japanese with English abstracts (see the supplemental table in the online data supplement).

Figure 1 Literature Review Process.

Number of Articles Describing NCDs

Of 160 cited articles, 3 articles described both cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease. We counted 3 articles for each disease category.

Of those 160 reports, 42 described NCDs that existed before the GEJE. The articles describing respiratory diseases were the most numerous. Then, 118 articles described NCDs that developed after the GEJE. Of those, 72 articles were related to mental health issues, followed by cardiovascular diseases, which accounted for 18 articles (Table 1). The disease-specific difficulties are presented in alphabetical order in the following section according to whether the disease affected the person before the GEJE or after the disaster.

Table 1 Number of Articles Reviewed by Disease Category

a Three articles described both cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease. We counted them in each disease category (references Reference Nozaki, Nakamura and Abe71 - Reference Aoki, Fukumoto and Yasuda73).

NCDs Existing Before the GEJE

Allergy

One article describing preexisting allergies was identified.Reference Minoura, Yanagida and Watanabe 13 According to the results of a questionnaire survey of 194 parents of children with a food allergy, almost all subjects faced lifeline disruptions, communication failure, and goods shortage at stores in affected areas after the GEJE, especially of allergen-free foods. Although 72% of the parents stocked some allergen-free food at their homes, 40% of them experienced insufficiency after the disaster. According to the parents’ responses, necessities at the time of the disaster were securing medicine, allergen-free food, and milk. The survey revealed that 43% of the children also had asthma; 14% of them developed an asthma attack attributable to increased house dust, cold environment, and stress. More than 70% of children with food allergies also had atopic dermatitis; 60% of them exhibited exacerbated symptoms because they could not take a shower for a few days or a few weeks because of lifeline disruption or because they lived in a shelter after the earthquake.Reference Minoura, Yanagida and Watanabe 13

Cancer

One article describing preexisting cancer was identified.Reference Akiyama, Seya and Murayama 14 Tohoku University Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital, and Senseki Hospital provided chemotherapy to patients with various cancers from immediately after the GEJE. However, the number of chemotherapy treatments at the 3 hospitals decreased in March 2011, the month the GEJE struck. According to a questionnaire survey of 85 patients who received chemotherapy, more than 60% experienced interruption of medical treatment attributable to traffic disruption and closing of the hospital. The survey also revealed that about 20% of the subjects forgot the name of their disease; 60% of subjects forgot the name of the medicine that they usually took.Reference Akiyama, Seya and Murayama 14

Cardiovascular Disease

Six articles describing preexisting cardiovascular diseases were identified.Reference Satoh, Kikuya and Ohkubo 15 - Reference Suzuki, Yoshihisa and Kanno 20 All articles that described blood pressure of hypertensive patients reported that their blood pressure rose significantly immediately after the earthquake and that the effect continued for about 2 weeks.Reference Satoh, Kikuya and Ohkubo 15 - Reference Tanaka, Okawa and Ujike 17 Disruption of antihypertensive medication, evacuation, and strong psychological stress were regarded as associated with exacerbation of hypertension.Reference Ito, Date and Ogawa 16 - Reference Nishizawa, Hoshide and Okawara 18 The occurrence of heart failure and tachyarrhythmia also increased from immediately after the earthquake through a 6 months after the earthquake.Reference Nakano, Kondo and Wakayama 19

Cerebrovascular Diseases

One article describing preexisting cerebrovascular diseases was identified.Reference Kobayashi, Endo and Inui 21 According to a questionnaire survey administered to 161 patients with epilepsy, about 30% of patients experienced a lack of stockpiled medication for 1 week after the GEJE, and 9 patients experienced a worsening of seizures. Even these patients were unable to access health care facilities because of the disruption of transport or lack of gasoline for automobiles. Some patients were unable to access their medicine even when they had reached a hospital because they had no information related to details by which the medicines were prescribed.Reference Kobayashi, Endo and Inui 21

Cognitive Impairment

Two articles describing preexisting cognitive impairment were identified.Reference Awata 22 , Reference Meguro, Akanuma and Toraiwa 23 People aged 60 years and older accounted for 65% of deaths from the GEJE. Elderly people, especially those with cognitive impairment, were unable to understand the situation at the time of the disaster. Those residing in coastal areas were unable to evacuate before the tsunami waves struck the coast. Aged people whose residences were damaged were forced to live as refugees at evacuation centers, which meant separation from neighborhoods and familiar places. The change of human relations and living environment caused a decrease of activities of daily living and opportunities for going out, and exacerbated difficulties related to their behavior and mental symptoms associated with cognitive impairment.Reference Awata 22

Disability

One article describing people with disability was found.Reference Tanaka 24 More than twice the number of children with some disability sustained injury or death from the GEJE than did children without disability. Immediately after the disaster, responders had difficulty readily confirming that people needing special assistance in evacuation, such as people with a physical disability and patients with a respirator, had evacuated safely. Although many supplies were donated from all over Japan, special supplies such as liquid nutrients for tube feeding, connectors, and aspirators were in shortage.Reference Tanaka 24

Gastrointestinal Disease

One article describing preexisting gastrointestinal disease was found.Reference Shiga, Miyazawa and Kinouchi 25 Of 546 patients with ulcerative colitis and 357 patients with Crohn’s disease, nearly 30% of patients experienced changes in daily nutritional intake after the disaster because of difficulty in obtaining foods of various types. Regarding medication, more than 10% of patients interrupted medication for 1 week or more because they had lost their medicines or could not consult with doctors. Psychological stress also led to relapse of ulcerative colitis.Reference Shiga, Miyazawa and Kinouchi 25

Mental Health Issues

Six articles describing studies of preexisting mental health issues were identified.Reference Matsumoto, Shirasawa and Iwadate 26 - Reference Usui, Hatta and Aratani 31 Following the GEJE, an increased number of patients with mental illnesses reported exacerbated symptoms and needed extra treatment and hospitalization because of shocking and severe experience such as deaths of family members, horrible sights of the tsunami, losses of employment and residences, and poor living conditions and diet.Reference Matsumoto, Shirasawa and Iwadate 26 According to a survey by Jichi Medical University Hospital, even patients with mental illnesses who lived distant from the affected areas exhibited worsened conditions.Reference Suda, Inoue and Inoue 27 Despite increasing medical needs, the function of most psychiatric hospitals sharply declined, which made life difficult for patients with mental illnesses who were in worse mental condition to receive medical treatment or mental care. Insufficiency of some related drugs, particularly antidepressants and anticonvulsants, also presented severe difficulties.Reference Matsumoto, Shirasawa and Iwadate 26 , Reference Kim 28 , Reference Suzuki and Kim 29 Continuing psychiatric treatment posed a major challenge after the GEJE.Reference Kim 28 , Reference Suzuki and Kim 29

Metabolic Disease

Six articles describing preexisting metabolic diseases were identified.Reference Nishikawa, Fukuda and Tsubokura 32 - Reference Kishimoto and Noda 37 The results of comparison between pre-earthquake and post-earthquake metabolic indexes, such as blood glucose levels and BMI and blood pressure, differed among the studies.Reference Nishikawa, Fukuda and Tsubokura 32 - Reference Tanaka, Imai and Satoh 35 However, most people with diabetes faced difficulties related to glycemic control because of inappropriate diet, less daily motion, difficulty of access to health care, and mental stress.Reference Fujihara, Saito and Heianza 33 - Reference Kishimoto and Noda 37 Medical teams were unable to obtain the information about what treatments the patients had received before the disaster because many had lost their medicine, medication records, and insulin kits.Reference Kishimoto and Noda 37 Moreover, that lack of information made glycemic control more difficult.

Neurological Disease

Three articles describing preexisting neurological diseases were identified.Reference Aoki 38 - Reference Kanamori, Nakashima and Takai 40 There were 155 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) residing in Miyagi prefecture at the time of the GEJE, 49 of whom were supported by home respiratory care with tracheostomies and ventilators. Among them, 2 patients were killed by the tsunami waves; 25 patients were forced to evacuate to hospitals. According to results of a questionnaire survey administered to patients with ALS or multiple system atrophy under respiratory care at their home, the most common reasons for hospitalization after the earthquake were residential collapse and power supply shortage. Their main concern at the time of the disaster was securing a reliable power supply.Reference Aoki 38

Renal Disease

Six articles describing preexisting renal diseases were identified.Reference Haga, Hata and Ishibashi 41 - Reference Haga, Hata and Yabe 46 All articles that described the blood pressure of patients with chronic kidney diseases reported that blood pressure was elevated significantly for 1 week after the earthquake compared to baseline.Reference Haga, Hata and Ishibashi 41 - Reference Tanaka, Nakayama and Tani 45 A remarkable blood pressure increase was observed in patients who were not taking any antihypertensive drugs after the disaster compared with those taking a hypertensive drug without interruption.Reference Tanaka, Nakayama and Kanno 44 , Reference Tanaka, Nakayama and Tani 45 Some patients endured insufficient hemodialysis length of time because of the insufficient water supply, frequent aftershocks, and impaired function of the nearby hospitals. In Soma Central Hospital, Hanawa Welfare Hospital, and En-jin-kai Suzuki Clinic, although all patients were able to continue to receive regular hemodialysis treatment 3 times a week immediately after the earthquake, the hemodialysis duration had to be shortened to 0.5 to 1 hour for about 1 month because of insufficient water supply and frequent aftershocks.Reference Tanaka, Nakayama and Kanno 44 , Reference Haga, Hata and Yabe 46

Respiratory Diseases

Eight articles describing preexisting chronic respiratory diseases were identified.Reference Yamanda, Hanagama and Kobayashi 47 - Reference Yanagimoto, Haida and Suko 54 At the Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital, for the first 60 days following the GEJE, 322 patients with respiratory diseases were about 20% of the new inpatients. Pneumonia was the most frequent disease, followed by acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma attacks, and progression of lung cancer. Patients with pneumonia and acute exacerbations of COPD were significantly older in 2011 than in previous years.Reference Yamanda, Hanagama and Kobayashi 47 A large number, about 40% of all patients, were hospitalized from evacuation centers. The possibility exists that the poor environment, with crowding, sleeping on the floor, cold temperatures, and unbalanced meals, exacerbated their diseases. Many patients experienced treatment disruption because of lost medicines, which worsened their symptoms.Reference Yamanda, Hanagama and Kobayashi 47 - Reference Ishiura, Fujimura and Yamamoto 49 Power failures throughout stricken areas also caused severe problems in patients treated under home oxygen therapy.Reference Kobayashi, Hanagama and Yamanda 48 , Reference Kobayashi, Hanagama, Yamanda and Yanai 50 - Reference Takechi 53 Seventy patients with home oxygen therapy in Ishinomaki region visited the Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital immediately after the GEJE to receive oxygen therapy.Reference Kobayashi, Hanagama and Yamanda 48 , Reference Kobayashi, Hanagama, Yamanda and Yanai 50 According to Sato’s survey, patients with little knowledge about home oxygen therapy and those who lived alone or with an elderly spouse tended to experience oxygen supply outages.Reference Sato, Morita and Tsukamoto 51

NCDs That Developed After the GEJE

Allergy

One article describing allergy development was identified.Reference Kikuya, Miyashita and Yamanaka 55 According to the results of a survey investigating the health needs of schoolchildren in affected areas, the prevalence of wheezing or eczema symptoms 1 year after the GEJE was higher than the Japanese average. The factors described above in the preexisting allergy section, such as unclean living environments, mental stress, and less opportunity for bathing, were also regarded as reasons underlying the development of allergies. Both symptoms were more frequent in children of lower grades in school.Reference Kikuya, Miyashita and Yamanaka 55

Cardiovascular Disease

We identified 18 articles describing the development of cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and acute myocardial infarction.Reference Ohira, Hosoya and Yasumura 56 - Reference Aoki, Fukumoto and Yasuda 73 Even if people did not have hypertension before the GEJE, their blood pressure rose immediately after the earthquake. People working as public employees at the time of the GEJE who had evacuated to temporary housing or who lived in coastal areas were at high risk of hypertension.Reference Ohira, Hosoya and Yasumura 56 - Reference Murakami, Akashi and Noda 59 The incidence of other cardiovascular events, such as pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), heart failure, and myocardial infarction, also increased.Reference Nakamura, Tanaka and Nakajima 60 - Reference Aoki, Fukumoto and Yasuda 73 The risk factors of DVT were living in crowded and small spaces such as that of an evacuation center or a personal car, lack of physical activity, and dehydration by insufficient water intake.Reference Ueda, Hanzawa and Shibata 68 , Reference Ueda, Hanzawa and Shibata 69

Cerebrovascular Disease

Seven articles describing the development of cerebrovascular diseases were identified.Reference Nozaki, Nakamura and Abe 71 - Reference Shibahara, Osawa and Kon 77 The number of patients who developed some cerebrovascular disease, such as cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and seizures increased after the GEJE.Reference Nozaki, Nakamura and Abe 71 , Reference Takegami, Miyamoto and Yasuda 72 , Reference Omama, Yoshida and Ogasawara 74 - Reference Shibahara, Osawa and Kon 77 Those patients were especially male, 75 years of age and older, and had sustained tsunami damage or injury. Increase of the patients and exacerbation of their symptoms was strongly related to the degree of tsunami damage.Reference Omama, Yoshida and Ogasawara 74 , Reference Omama, Yoshida and Ogasawara 75 The number of patients who had seizures also increased significantly during the 2 months after the GEJE. Shibahara expected that the lack of anticonvulsant therapy would contribute to worsening of their symptoms.Reference Shibahara, Osawa and Kon 77

Cognitive Impairment

Three articles describing development of cognitive impairment were identified.Reference Hikichi, Aida and Kondo 78 - Reference Ishiki, Okinaga and Tomita 80 The GEJE strongly affected cognitive functions of elderly people. Several factors of cognitive impairment have been reported, such as changes in living circumstances, loss of families or friends, and loss of daily activities.Reference Hikichi, Aida and Kondo 78 - Reference Ishiki, Okinaga and Tomita 80 To maintain their cognitive functions, out-of-home activities and walking should be suggested to elderly people after a large-scale disaster.Reference Ishiki, Okinaga and Tomita 80

Disability

One article describing the increase of people with disability was identified.Reference Tomata, Suzuki and Kawado 81 The disaster caused not only cognitive impairment but also functional disability to aged people. According to Tomata et al’sReference Tomata, Suzuki and Kawado 81 study, disability prevalence in disaster-affected areas increased significantly (coastal 14.7%, inland 10.0%) during the 3 years after the GEJE compared to nondisaster areas (6.2%, P<0.001).

Gastrointestinal Disease

Eight articles describing the development of gastrointestinal diseases were identified, of which 6 described peptic ulcers that developed after the GEJE. Reference Kanno, Iijima and Abe 82 - Reference Tominaga, Nakano and Hoshino 89 The number of patients with peptic ulcers increased in 2011 compared with 2010.Reference Kanno, Iijima and Abe 82 - Reference Yamanaka, Miyatani and Yoshida 84 The proportion of non-Helicobacter pylori and non-NSAID (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug) peptic ulcers was increased significantly after the GEJE. Psychological stress might have caused those cases.Reference Kanno, Iijima and Abe 82 , Reference Yamanaka, Miyatani and Yoshida 84 , Reference Kanno, Iijima and Koike 86 According to some studies, living in evacuation centers and taking anti-thrombotic drugs were the 2 major factors underlying hemorrhagic ulcers after the disaster.Reference Kanno, Iijima and Koike 86 , Reference Kanno, Iijima and Koike 87 Evacuation center residents experienced various gastrointestinal symptoms such as weight loss, constipation, appetite loss, and nausea.Reference Inoue, Nakao and Kuboyama 88 Food and water security was a major difficulty in the acute phase of the disaster. In the subacute phase, constipation and major gastrointestinal problems occurred because of changes in lifestyle, consuming foods with little dietary fiber, and less water intake. In the chronic phase, various gastrointestinal diseases occurred or showed deterioration caused by forced life changes and difficulties related to the acute and subacute phase. Supply shortages of drugs worsened their condition.Reference Tominaga, Nakano and Hoshino 89

Mental Health Issues

A total of 72 articles describing development of mental health issues were identified.Reference Sone, Nakaya and Sugawara 90 - Reference Kato, Uchida and Mimura 161 People exhibited psychological symptoms of various kinds, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and insomnia. People who had the following characteristics or status were likely to have psychological distress: female, lost their family members, experienced residential damage, had anxiety about radioactive contamination, had difficult economic status, and had weak social support. Reference Sone, Nakaya and Sugawara 90 - Reference Nagaoka and Uchida 103 , Reference Sawa, Osaki and Koishikawa 105 - Reference Niwa 113 , Reference Matsubara, Murakami and Imai 117 - Reference Kuwabara, Araki and Yamasaki 120 , Reference Teramoto, Matsunaga and Nagata 122 , Reference Matsumoto, Yamaoka and Inoue 124 - Reference Yokoyama, Otsuka and Kawakami 129 , Reference Yabe, Suzuki and Mashiko 132 - Reference Kunii, Suzuki and Shiga 140 , Reference Nishi, Koido and Nakaya 143 , Reference Tuerk, Hall and Nagae 144 , Reference Onose, Nochioka and Sakata 147 , Reference Sakuma, Takahashi and Ueda 151 , Reference Tsuno, Oshima and Kubota 152 , Reference Usami, Iwadare and Kodaira 155 Psychological effects of the GEJE were severe, affecting not only adults but also children. Students of high schools that sustained extensive damage by the tsunami or the earthquake and who used temporary school buildings showed significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety, with significantly lower resilience compared to students of high schools with no damage.Reference Usami, Iwadare and Watanabe 131 , Reference Fujiwara, Yagi and Homma 133 , Reference Usami, Iwadare and Kodaira 155

Metabolic Diseases

Six articles describing the development of metabolic diseases were identified, all of which described negative effects of evacuation on metabolic indexes.Reference Tsubokura, Takita and Matsumura 162 - Reference Satoh, Ohira and Hosoya 167 The metabolic indexes of body weight, BMI, waist circumference, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and HDL cholesterol level deteriorated. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and diabetes was higher among evacuees living in temporary housing than among nonevacuees.Reference Tsubokura, Takita and Matsumura 162 - Reference Satoh, Ohira and Hosoya 167 Deterioration of the metabolic indexes and diseases among evacuees is expected to be related to changes in lifestyle such as poor diet, decreased physical activity, and loss of social networks.Reference Satoh, Ohira and Hosoya 163 , Reference Hashimoto, Nagai and Fukuma 164 , Reference Satoh, Ohira and Hosoya 167

Orthopedic Disease

Two articles describing the development of orthopedic diseases were identified.Reference Hagiwara, Yabe and Sugawara 168 , Reference Yabe, Hagiwara and Sekiguchi 169 Two questionnaire surveys revealed that the incidence of new-onset lower back pain at 3 years after the GEJE was 10% to 15%. In both surveys, new onset of lower back pain was associated with economic status, which posed a subjective economic hardship or decreased income rather than affecting the housing situation. Results of both studies suggest that low economic status might have increased psychological stress, such as depression and anxiety, consequently affecting the perception of pain.Reference Hagiwara, Yabe and Sugawara 168 , Reference Yabe, Hagiwara and Sekiguchi 169

Otolaryngological Diseases

One article describing the development of otolaryngological disease was identified.Reference Hasegawa, Hidaka and Kuriyama 170 According to an investigation at Soma General Hospital, which was the only hospital in Soma City providing full-time otolaryngological medical care, the number of cases of vertigo, dizziness, Meniere’s disease, and acute low-tone sensorineural hearing loss increased from immediately after the disaster and slightly decreased in the third year. Soma General Hospital is 44.5 km distant from the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. The study revealed that 4.8% of patients with otolaryngological diseases had concomitant depression and other mental diseases.Reference Hasegawa, Hidaka and Kuriyama 170

Renal Disease

One article described the development of renal disease.Reference Satoh, Ohira and Nagai 171 According to Satoh et al’sReference Satoh, Ohira and Nagai 171 survey of residents living near the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant, evacuation was not significantly associated with a low estimated glomerular filtration rate or proteinuria, which was the risk of chronic renal diseases. However, this study suggested the importance of lifestyle and dietary advice related to obesity prevention, sodium-restricted diet, and treatment for metabolic disorders to prevent the development of chronic renal diseases.Reference Satoh, Ohira and Nagai 171

Skin Disease

One article describing development of skin disease was identified.Reference Sato and Ichioka 172 It reported a 10 times higher incidence of pressure ulcers (bedsore) in affected areas after the GEJE than in the normal phase. Patients were mostly elderly people. The loss of alternating-pressure air mattresses, insufficiency of mattresses and human resources at evacuation centers and health care facilities, and nutritional impairments were risk factors that led to pressure ulcers after the GEJE. Identifying individuals at risk for pressure ulcer development and effective use of limited resources are fundamentally important.Reference Sato and Ichioka 172

DISCUSSION

Characteristics of the Study

This literature review is the first related to NCDs after a large-scale natural disaster. We searched for articles published during the 5.5 years after the GEJE. The articles described circumstances of patients with NCDs after the disaster throughout various phases.

Summary of Evidence

Since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake occurred in 1995, emergency medical systems to be used after hugely destructive disasters, including 4 main systems, were developed in Japan. Up to that time, most casualties of natural disasters were cases of injury. These 4 main systems were as follows: (1) a disaster base hospital, in fact, a hub hospital for medical treatment after disasters; (2) Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs), with trained medical teams providing medical treatment or care during the acute phase of a disaster; (3) wide area transport systems, which are systems for transferring patients from affected areas to unaffected areas where patients can receive sufficient medical care; and (4) an emergency medical information system, a medical-information-sharing system transcending facilities and areas. Soon after the GEJE in 2011, 340 DMATs with 500 members were dispatched to affected areas. They transported severely ill or injured patients from devastated areas to safe areas by airplane or helicopter. These activities were conducted for the first time after a disaster in Japan. Improvement of the emergency medical system has been widely acknowledged.Reference Koido, Kondo and Ichihara 173 , Reference Nakata 174 Public health issues were highlighted, including difficulties of patients with NCDs after the GEJE. This study clarified some important findings and problems.

First, the results clarified that most of the academic literature reflects the main concern of the researchers. Many studies of mental health issues and cardiovascular diseases were reported. Particularly, more than 30 reports described psychological disorders and PTSD deriving respectively from the sight of the huge tsunami, loss of acquaintances, and aftershocks (see the supplemental table in the online data supplement). The GEJE triggered the establishment of Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Teams, each of which consists of a psychiatrist, a nurse, and a logistician. Mental health care will be in the spotlight in future disasters. However, for some NCDs such as allergy, cancer, and skin disease, one or only a few articles have described conditions. They have not adequately clarified the related circumstances. It is necessary to clarify their situation and difficulties related to disasters and to prepare sufficient medical measures for people who are likely to need such measures.

Second, common features of health problems were observed for many NCDs. The number of patients with NCDs increased. The health condition of most of these patients worsened after the GEJE. All disaster-affected people were influenced by the difficulty of continuing medical treatment and taking medicine, poor living environment, stress, and lack of nutritious food and exercise opportunities. Patients with NCDs were more influenced by these difficulties. Although the medical priority following a disaster is lifesaving, all survivors’ healthy life is important. Patients with NCDs are vulnerable during and after disasters. Health care workers must recognize their vulnerability and devote attention to their condition, irrespective of their continued residence in their own homes or of their evacuation to residential centers or temporary housing.

Third, the results revealed several disease-specific problems. In patients with respiratory diseases or neurological diseases who had received respiratory treatment at their home as home oxygen therapy or via respiratory equipment, the interruption of treatment after disasters is fatal. Education before disasters, including preparation of oxygen cylinders, handling methods, and emergency support systems, is necessary for patients, especially for single-person households or older couples. Some special supplies such as allergy-free foods and tube feeding nutrient sets were insufficient in relief supplies delivered to evacuation centers. Some elderly people with cognitive impairment were unable to evacuate before the tsunami struck because there were no systems warning them of danger. For that reason, they were unaware of the urgent situation.

According to the aging of society, coordination and preparedness for disasters among specialists, general practitioners, nurses, care managers, and family members are crucially important for disease-specific problems. Particularly, patients who have continued living in their own homes or evacuated to a relative’s home are difficult to find and to treat unless they come forward.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review clarified common difficulties and problems specific to NCDs after the GEJE. The interruption of medications and treatments and the negative effects of evacuation were the most common reasons underlying exacerbation of preexisting NCDs. Awareness and appropriate response to newly developed NCDs including mental health issues are also required. We are living in an era of an aging society. Therefore, the number of people with NCDs will definitely increase. It is critically important to clarify difficulties arising from past disasters and to take countermeasures for NCDs to prepare for future disasters.

Funding

This study was supported by a Tokutei Project Grant from IRIDeS and JSPS KAKENHI grant number 16K08857.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2017.63