In spring 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) spread across the United States and impelled universities to switch to online instruction. Although the pandemic trajectory remains uncertain, Reference Moore, Lipsitch, Barry and Osterholm1 scientific consensus is that the pandemic will continue into the fall. 2 Many epidemiologists have warned of a rebound of cases, due in part to a relaxation of social distancing. Reference Fung, Antia and Handel3,Reference Handel, Longini and Antia4 One university president wrote recently, “The COVID-19 virus will remain a fact of life this autumn.” Reference Daniels5 University student life, including classroom instruction, cafeterias, residential halls, and sport and cultural activities, provides ample opportunities for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission. Alleged “failure” to protect students from SARS-CoV-2 infection on campus carries legal risks too, as some may file class-action law suits against their universities, as in a recent example. Reference Struck6 To reopen campuses and avoid outbreaks this fall will require careful deliberation.

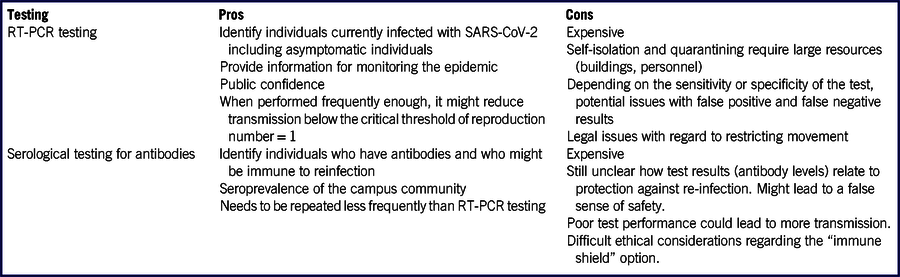

Anticipating the Fall Semester, universities are deliberating whether, and to what extent, they should reopen their campuses to in-person instruction. Reference Fain7,Reference Staff8 As of June 23, 64% of 1030 US colleges surveyed plan for in-person instruction, while 24% planned for online or hybrid models. Reference Staff8 As universities announce their intentions, all have placed public health considerations at the top of criteria for reopening. In May, the American College Health Association (ACHA) issued its guidelines on campus reopening, Reference College Health Association9 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published its “Considerations.” 10 Both documents provide general information and infection control guidelines. Neither document discusses in detail the feasibility of using extensive viral or serological testing strategies, which have been proposed by some as potential important control strategies. Reference Weitz, Beckett and Coenen11,12 To the best of our knowledge, the implementation of an extensive viral or serological testing program was unbeknownst to most university campuses before the COVID-19 pandemic. To further the debate on reopening university campuses for in-person instruction without a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine, in this policy analysis, we discuss the practical aspects of implementing such testing strategies on college campuses (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Mass RT-PCR Testing for SARS-CoV-2 and Mass Serological Testing for Antibodies Against SARS-CoV-2

RT-PCR Testing, Contact Tracing, Isolation, and Quarantine

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests can be used to identify virus-shedding individuals. ACHA recommends campus-wide syndromic surveillance and that universities should ensure “access to immediate viral testing for all students, faculty, or staff with symptoms.” Reference College Health Association9 Given that SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted presymptomatically, Reference He, Lau and Wu13 ACHA recommends “viral surveillance of asymptomatic students” where possible. Reference College Health Association9

As an example, the University of California San Diego is extending mass testing to asymptomatic individuals. 12 The voluntary program will provide students with RT-PCR self-test kits and will test “60 to 90%” of the campus population “on a recurring basis.” 12 Recurrent mass testing could be useful in detecting asymptomatic individuals and reducing transmission to others. For a basic reproduction number of 2.5, Reference Wu, Leung and Leung14 2 of 3 potential transmissions must be prevented by prompt diagnosis and isolation to keep the reproduction number <1. Given an incubation period of around 5-6 days, Reference Lauer, Grantz and Bi15,16 and the assumption that the majority of transmission occurs after symptom onset, Reference He, Lau and Wu13,Reference Liu17 even testing everyone weekly, followed by rapid isolation and quarantine of infected individuals and their close contacts, respectively, 18 might not be enough to prevent widespread campus transmission.

However, there are serious caveats. Mass testing is expensive. Reference Nadworny19 Medicare pays $100 for laboratory tests using high-throughput technologies for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. 20 Using this pricing as a benchmark, each round of testing a campus of 10,000 individuals would cost 1 million dollars. Mass testing is logistically challenging, too. For example, to finish self-testing 10,000 individuals every week, a daily rate of self-testing 1429 individuals is needed. A staggered schedule of return and testing may make the logistics more manageable. Many universities may not have access to laboratories that can process a large number of specimens quickly enough so that results can be delivered in time to be relevant for contact tracing and isolation. Universities might not be able to rely on external laboratories for large testing programs because of cost and limits on throughput.

The program’s effectiveness in preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission would depend upon high levels of voluntary participation, and a ready ability to support self-isolation and quarantine (eg, single residential rooms for isolated and quarantined students, staff monitoring of compliance, recording symptoms and clinical status, providing food and medical care). Many universities may lack the space and personnel needed to conduct such programs, especially during times when campus outbreaks are detected. 18 Finally, many universities may lack the legal authority to enforce isolation and quarantine or otherwise to limit students’ freedom of movement.

Further challenges stem from the fact that tests are imperfect and produce both false negative and false positive results. Reference Wang, Wang and Chen21,Reference Ai, Yang and Hou22 False negative results may lead to otherwise avoidable transmission. Some rapid tests are reported to have a sensitivity as low as 85%, Reference Stein23 ie, there will be 15 false negatives for every 100 SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals. In programs relying on unsupervised self-collected nasal specimens, false negative results may arise from improper collection technique or transport. As long as SARS-CoV-2 prevalence on campus remains low, false positive results might be a larger concern, as the positive predictive value may be low unless the specificity is as high as 100%. Reference Gressman and Peck24 This could lead to healthy students being misdiagnosed as being infected, and thus isolated, further exacerbating the resource and legal challenges mentioned above.

Specificity can be increased if 2 tests are required to confirm a case. However, this will substantially increase the cost and workload of mass testing. Specificity can also be increased if only symptomatic individuals are tested. However, because asymptomatic transmission is well documented, Reference He, Lau and Wu13,Reference Gao, Xu and Sun25 focusing on only symptomatic individuals is not an option if testing serves as the main control strategy. Overall, the profound logistical challenges of a test-and-isolate strategy prevent it from being the mainstay of outbreak control.

Serological Testing for Antibodies and “Immune Shield” Strategy

Another testing strategy that has been proposed is to apply serological testing to identify individuals who have developed protective antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and assign them as “immune shields.” Reference Weitz, Beckett and Coenen11 Others have discussed the idea of issuing immunity certification, Reference Hall and Studdert26 or immunity-based licenses, Reference Persad and Emanuel27 to individuals with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Assuming such individuals are immune to reinfection, they can be deployed to provide “shield immunity” to preferentially interact with susceptible or infected individuals, thus reducing transmission. Reference Weitz, Beckett and Coenen11,Reference Kraay, Nelson and Zhao28 A model showed that such an immune shielding approach could potentially lead to a reduction in outbreak size. Reference Weitz, Beckett and Coenen11

While conceptually sound, it is unclear if such a serological testing-based strategy is viable for college campuses. First, the amount of protection provided by a given level of antibodies, which the test measures, is unknown. Reference Clapham, Hay and Routledge29 Second, it is uncertain for how long immunity might last. Reference Harris30,Reference Karimi31 There is evidence that immunity against SARS-CoV-2 might wane quickly. A study found that 40% (12/30) of asymptomatic individuals and 12.9% (4/31) of symptomatic individuals became IgG-negative 8 weeks after discharge from hospitals. Reference Long, Tang and Shi32 Third, false positives are a concern. Reference Karimi31,Reference Cairns33 If an individual is placed into an “immune shield” position despite not actually being immune, this could lead to an increase in transmission. Reference Kraay, Nelson and Zhao28 Fourth, preliminary results of seroprevalence studies suggest that immune individuals will be in short supply. A meta-analysis of multiple seroprevalence studies using Bayesian hierarchical models, Reference Levesque and Maybury34 found that seroprevalence is low among the populations investigated, with 2-6% in Los Angeles County, California, Reference Sood, Simon and Ebner35 0-2% in Santa Clara County, California, Reference Bendavid, Mulaney and Sood36 1.6-2.6% in San Miguel County, Colorado, and 15-41% in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Cautious interpretation of studies where participants were recruited by means of social media advertisement as a convenience sample, Reference Bendavid, Mulaney and Sood36 is needed given potential selection bias; accounting for the uncertainty in the sensitivity and specificity of the tests is also recommended. Reference Gelman and Carpenter37,Reference Bennett and Steyvers38 Concerns remain whether studies in certain COVID-19 hotspots are representative of the general population nationwide. It is likely that, in August 2020, universities can expect <10% of returning students being potentially immune while the majority will remain susceptible. If 5% of a campus community were to be seropositive, this would mean 1,000 individuals on a campus of 20,000. If these seropositive individuals could be deployed to have 10 times as many contacts as other groups, it would lead to a reduction of ~31% in transmission, not enough to get the reproduction number below 1. Reference Weitz, Beckett and Coenen11

Furthermore, the logistical challenges are obvious. When semester begins, everyone needs to get tested rapidly. Then, seropositive individuals will be trained to fill positions with high contact rates (eg, campus bus drivers, food service workers, residential facility managers). Both matching positions to talents and on-the-job training take time. Cost is another concern. Medicare pays $42-45 per SARS-CoV-2 serological test. 20 This translates into a price tag of $840,000-$900,000 for a 20,000-strong campus. Ethical issues have also been raised. Reference Voo, Clapham and Tam39 If student employment opportunities are limited, and they are open to immune people only, would students deliberately get themselves infected as in “COVID-19 parties” Reference Baker40 so that they can take up those jobs? Conversely, there are media reports that some recovered individuals have been stigmatized. Reference Karimi31 It is also known that, currently, vulnerable minorities are more likely to be infected. Reference Dyer41 Would it be equitable to ask those individuals who were infected because they were unable to shelter-at-home to perform extra duties as “immune shields”? Thus, with all these logistical, financial, and ethical concerns, while the serological testing and immune shield strategy might be feasible in subpopulations such as health-care workers, it appears not to be a promising control strategy for college campuses.

CONCLUSIONS

We discussed some practical considerations for 2 potential testing-based control strategies as applied to college campus reopening: RT-PCR testing followed by case-patient isolation and quarantine of close contacts; and serological testing followed by “immune shields.” Given the logistic and ethical issues, neither approach appears to be viable as a main strategy. We do believe they could be used as supplementary strategies or applied to specific groups (eg, individuals with high contact rates). Unless the issues we discussed above can be resolved in such a way that using mass testing as main control strategies becomes viable, the main nonpharmaceutical interventions will remain methods based on social distancing and personal protective behaviors until vaccines become available. Online or hybrid instruction this fall will significantly reduce the risk of on-campus outbreaks. Reference Huang and Austin42 For those planning for in-person instruction, Reference Staff8 social distancing measures, including capping class size at a small number, Reference Weeden and Cornwell43 and the adoption of personal protective behaviors, including universal facemask wearing in public space, Reference Dhillon, Karan and Beier44 will be required to reduce—but not eliminate—on-campus transmission. Reference Gressman and Peck24 Given the ongoing debate in some university systems whether to make facemask-wearing in public mandatory, Reference Shearer45 and the challenges of enforcing social distancing among students outside the classroom setting, there is a sizeable risk of on-campus COVID-19 outbreaks when in-person instruction resumes on college campuses this fall. Reference Gressman and Peck24

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Frederic E. Shaw, MD, JD, and Gerardo Chowell, PhD, for their critical comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. This article is not part of ICHF’s CDC-sponsored projects.

Funding

ICHF acknowledges salary support from the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (19IPA1908208).

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article do not represent the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the United States Government.