International communicable disease crises of recent years have highlighted the need for countries to assure their preparedness to respond effectively to public health emergencies.Reference Oshitani1-Reference Quaglio, Goerens and Putoto3 Further, implementation of the revised International Health Regulations (IHR), a 2013 decision of the European Parliament and Commission on cross border health threats, and concerns over the effectiveness of the initial response to the Ebola crisis, have led to calls for countries to assess and report on the effectiveness of their public health emergency preparedness and response organization and plans.4-6

Despite this, there is only limited knowledge of the methods by which countries assess the state of their preparedness for public health emergencies. There is also little consensus regarding the system elements that should be included in a preparedness system assessment and their validity as predictors of country responsiveness during an actual emergency.Reference Savoia, Massin-Short and Rodday7,Reference Khan, Fazli and Henry8 Available assessment tools were reviewed by Asch et al.Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9 and Nelson et al.Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10 in 2005 and 2007, respectively, expressing concerns over the validity of methodologies then in use. Since then, a number of assessment methodologies and tools have been developed, with varying relevance to public health emergency preparedness.

The objective of this study was to review the characteristics and utility of available tools and methodologies for assessment of countries’ public health emergency preparedness. The underlying purpose of this review was to guide development by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) of methodological concepts and tools to support public health emergency preparedness in European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) member states.

METHODS

Existing tools were located through 3 lines of inquiry: (1) MEDLINE search of peer-reviewed literature, (2) online search of gray literature in public health and civil defense websites, and (3) e-mail contact with ECDC designated emergency preparedness respondents for all EU/EEA member states, to identify nationally developed tools that had not been published elsewhere. Methods 1 and 2 were independently performed by 2 reviewers. The review was conducted between October and December 2014, with updates up to August 2018.

For the MEDLINE search, following a pilot exploration of the data sources and literature, all key words/MeSH terms that could be related with public health emergency preparedness assessment tools were included, and search filters were chosen to be non-restrictive in order to increase search sensitivity. These are given in Table 1. Inclusion criteria were (1) Period: 2000–2017; (2) Languages: reports published in English, Spanish, French, German, or Italian; (3) Category: humans; (4) Scope: subnational, national, or international; (5) Type of hazard: generic (ie, all-hazards approach), or pandemic influenza; and (6) Presence of a checklist, indicators, or measures to assess national public health emergency preparedness status. Civil protection emergency assessment tools were excluded if they did not include public health or health care aspects of the emergency response. The gray literature search included international and national public health and civil defense websites.

TABLE 1 MEDLINE and Gray Literature Search Strategies

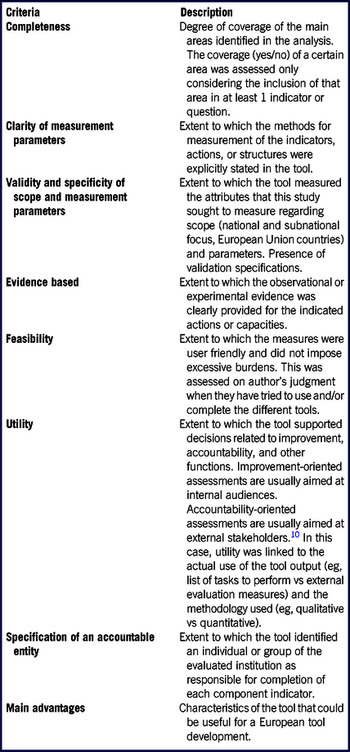

A framework to review and compare the identified tools was developed by the investigators, drawing substantively on criteria developed by Nelson et al.Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10 and Asch et al.Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9 Complementary indicators were extracted from these publications and combined in a single analytical framework, together with 2 further indicators developed by the authors (“completeness,” “main advantages”) (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Evaluation Framework

Modified from Asch et al.Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9 and Nelson et al.Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10

RESULTS

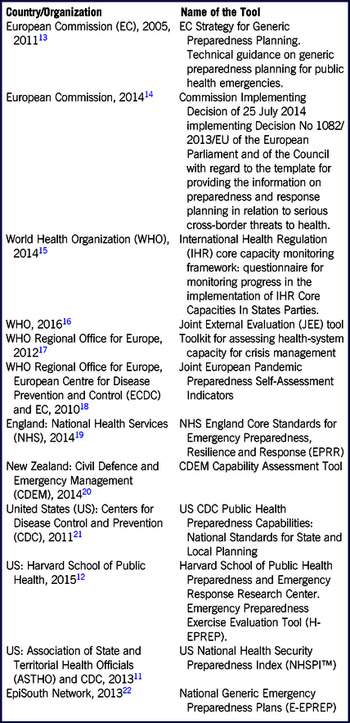

A total of 1459 peer-reviewed articles were retrieved and screened for eligibility. Only 2 assessment tools meeting the quality criteria were identified through a peer-review literature search: United States National Health Security Preparedness Index (NHSPI™)11 and Harvard School of Public Health Emergency Preparedness Exercise Evaluation ToolFootnote a (H-EPREP).12 Another 9 tools were identified from the search of public health and civil defense websites: European Commission technical guidance on generic preparedness planning for public health emergencies13 and template for providing information on preparedness and response planning in relation to serious cross-border threats to health14; World Health Organization (WHO) questionnaire for monitoring progress in the implementation of IHR Core Capacities In States Parties15 and Joint External Evaluation Tool (JEE)16; Toolkit for assessing health system capacity for crisis management of the WHO Regional Office for Europe17; Joint European Pandemic Preparedness Self-Assessment Indicators18; National Health Services England Core Standards for Emergency Preparedness, Resilience, and Response (EPRR)19; New Zealand Civil Defence and Emergency Management (CDEM) Capability Assessment Tool20; and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public Health Preparedness Capabilities.21 One further tool was identified by an ECDC national respondent: the EpiSouth National Generic Emergency Preparedness Plansa (E-EPREP).Reference Sizaire, Belizaire and de Pando22

The 12 tools identified are summarized in Table 3. All were published between 2009 and 2016. Seven of the 12 tools were developed by international authorities or organizations.13-18,Reference Sizaire, Belizaire and de Pando22 The other 5 were country-specific: from England,19 New Zealand,20 and the United States.11,12,21 Some of the tools developed by international organizations had a primary focus on voluntary country level implementation.13,17,18,Reference Sizaire, Belizaire and de Pando22 Others had an apparent primary rationale of required or recommended reporting under international or European regulations.14-16

TABLE 3 Summary of Tools Identified for Comparison

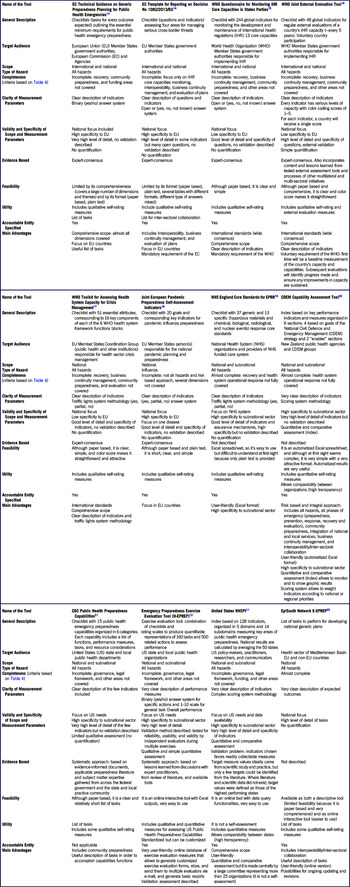

Appraisal of the tools according to the evaluation framework is summarized in Table 4. All tools identified had governmental or institutional authorities as the principal target audience and specified an accountable entity, but with varying degrees of detail. Although all tools had public health emergencies as a primary focus, they varied in their relative emphasis on various aspects of emergency preparedness, including health system resilience and the wider civil emergency protection function. All except 118 took an all-hazards approach, although they mainly focused on communicable (infectious) disease emergencies with some additional sections for other types of public health hazard such as chemical or radiological events.

TABLE 4 Evaluation Framework and Comparison of Identified Tools

The key assessment areas included in each of the tools are outlined in Table 5. Some areas were common to nearly all tools, with varying degrees of detail and methodological approaches, for example, interoperability and inter-sectoral collaboration, crisis management and operations, planning, communication and information systems, and human resources and capability development. Other assessment areas were addressed less frequently, for example, recovery, community preparedness, cross-border issues, or ethical aspects.

TABLE 5 Comparison of Key Areas Addressed in Identified Tools

Most tools identified provided little or no information on the criteria or decision processes used to identify the measures included in them, or the evidential approach taken for their development. Exceptions included the JEE,16 CDC,21 H-EPREP,12 and NHSPI11 tools. In most cases, the development of preparedness standards appeared to be based primarily on consultations with groups of experts. Only a minority of tools attempted to describe a conceptual and strategic framework underlying their design.11,12,21 The Civil Defence and Emergency Management Tool20 from New Zealand had the most comprehensive, logical, and updated framework, consistent with current concepts of health emergency preparedness.Reference Nicoll, Brown and Karcher23,28

Most of the selected tools had clear measurement parameters, with different methodological formats and complexity. These varied from a detailed list of tasks13-15,21,Reference Sizaire, Belizaire and de Pando22 to simple qualitative scales,12,16-19 through to more complex scoring systems.11,20 Four of the tools included a quantitative element: JEE,16 CDEM,20 H-EPREP,12 and NHSPI.11 The CDEM tool had a scoring system with weighted indicators that can be customized according to national or regional priorities.20

Seven of the tools were paper-based only, with no electronic informatics to facilitate use.13-18,21 Two were presented for use as an Excel file (NHS19 and CDEMReference Nicoll, Brown and Karcher20), and 3 had online modalities (H-EPREP,12 NHSPI,11 and E-EPREPReference Nicoll, Brown and Karcher22). Two allowed a degree of customization by the user: CDEM20 and H-EPREP.12 H-EPREP12 was an exception, providing for the generation of customized exercise evaluation forms, storage, transmission to multiple evaluators by e-mail, and generation of basic reports.

DISCUSSION

The use of systematic methods and tools for system assessment should have substantive benefits for the preparedness of countries for public health emergencies. The tool infrastructure should in itself have symbolic value to help communicate a coherent view of the emergency preparedness system to all participants. This should cover all of the elements critical to ensuring an effective response, including effective collaboration across sectors and between countries in responding to cross-border events. The systematic assessment of these elements should enable gaps and weaknesses to be proactively identified and addressed. To achieve this, tools should include assessment items, which are valid indicators of actual performance in an emergency. They should be available in user-friendly electronic modalities and include quantitative elements to support the monitoring of system preparedness over time and voluntary benchmarking with others, to promote learning and system improvement.

We have identified 12 presently available tools to support assessment of country preparedness for public health emergencies. Most tools were found through national and international websites, and it is possible that more may have been identified through gray literature in languages other than those included in this search, at subnational level, and sources such as postgraduate theses.

Few of the identified tools meet all of the above requirements. We acknowledge a potential limitation of our appraisal in that the tools were evaluated as a desktop exercise based on a priori criteria; however, the evidence base from user experience of the presently available tools is almost non-existent.

Our review suggests some possible contributing perspectives on this present situation. Available tools appear to have been developed with somewhat different primary aims and methodological approaches. Most tools developed by international agencies and 1 in the United States appeared to focus primarily on standard reporting requirements to which countries and states are subject. Exceptions included the self-evaluation checklists developed by the European Commission13 and the WHO Regional Office for Europe,17 which appear to be designed explicitly for country use. Tools developed by national authorities provide a primary focus on the evaluation needs of the country but may not extrapolate well for use by others, given country-specific characteristics of health and public health emergency response systems. Further, country-level tools may have less utility for subnational (regional, local) jurisdictions, and viceversa.

Country preparedness evaluations need to assess not only plans and capacities, but also system capabilities for effective response to actual emergencies. Several tools relied heavily on input data relating to system capacities and resources; while information concerning these is often readily available, it may be only indirectly predictive of the capability to respond to an emergency. Nelson et al. observed in 2007 that the few tools then available to assess preparedness status tended to focus on capacities, and little evidence existed that linked specific structures with the ability to execute effective response processes, noting that “structural measures may not be valid indicators of preparedness.”Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10 In reporting on a review of national influenza pandemic preparedness plans in the EU in 2012, Nicoll noted that some national authorities had ceased further preparedness development after producing written plans and had neither developed operational aspects nor tried to assess whether they would work in practice.Reference Challen, Lee and Booth24 The present study suggests only modest advance in this respect; among the identified tools, only the CDEM,20 H-EPREP,12 and JEE16 tools included significant consideration of system capabilities, as well as capacities.

The evidence base linking preparedness capacities and capabilities to health outcomes remain weak.Reference Savoia, Massin-Short and Rodday7,Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10 Asch et al. noted in 2005 that most instruments for assessing public health emergency preparedness relied excessively on subjective or structural measures and lacked a scientific evidence base.Reference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9 Previous literature reviews have found that the majority of journal articles were commentaries and anecdotal case studies, based on qualitative analyses,Reference Khan, Fazli and Henry8,Reference Abramson, Morse, Garret and Redlener25-Reference Agboola, Bernard, Savoia and Biddinger27 a situation unchanged in our present literature search in support of this critical tools analysis (to be reported separately). One systematic review concluded that most studies lacked a rigorous design, raising questions about the validity of the results.Reference Savoia, Massin-Short and Rodday7 It appears that more and better quality research into public health emergency management is needed for the development of useful assessment tools, and the validity of presently assessed system elements as predictive of actual response capability remains largely unverified. This is also the conclusion of the developers of other tools, which attempted to provide some evidence-based approach, who ended up relying mainly on lessons learned documents11,12,16,21 (see Table 4). A focus of future research should include the comparison of preparedness system a priori assessment scores and the actual system performance outcomes in real-life incidents and emergencies.

As the tools reviewed did not have a documented strong evidence base, there was only partial consensus on the system elements critical for public health emergency preparedness, and how they may be assessed or measured. Although some system areas were common to most tools, there was significant diversity in the system elements included and their emphasis across the tools reviewed, and in the indicators or standards used to measure their effective presence. “The problem lies not in the absence of standards per se, but in the multiplicity of overlapping (and sometimes conflicting) standards.”Reference Nelson, Lurie and Wasserman10,28

One issue underlying indicator development appears as differing preferences for standardizing all system measures, or leaving countries’ flexibility to modify, add, or delete them. Some authors have recommended standardization of all assessment measuresReference Asch, Stoto and Mendes9,Reference Simpson and Katirai29 in order to facilitate comparisons, either to a “gold standard” or between countries. However, some emergency response leaders consider that this is less useful than a flexible country-specific tool, given different country administrative structures and health care systems. Respondents to the EU pandemic influenza preparedness review in 2009 considered that “instead of [standardized] indicators, it would be more useful to develop a tool describing the main areas for consideration in pandemic influenza preparedness planning. Each country may then add its own criteria, indicators or outcomes for determining whether something is in place.”Reference Nicoll, Brown and Karcher23 This choice, in turn, appears to also reflect divergent views on the perceived value of sharing country information and benchmarking with others. In the same review, “a number of member states made it clear to the ECDC that the country specific results should only be known to the country […] and that specifically there would be no ‘league tables.’”Reference Nicoll, Brown and Karcher23

Few tools were available in user-friendly, electronic modalities that could facilitate data gathering, analysis, and dissemination and discussion of results by participants and stakeholders. H-EPREP12 was an exception, as it also allowed the generation of customized exercise evaluation forms, storage, transmission to multiple evaluators by e-mail, and generation of basic reports. Developers should therefore be encouraged to produce assessment tools in more user-friendly modalities. Inclusion of quantitative scoring systems usefully support the monitoring of progress in the development of a country’s public health emergency preparedness over time. Such quantitative scoring systems can also facilitate voluntary benchmarking with other countries. However, few tools included this feature. Only 2 tools had been published in a manner accessible to a conventional literature search28,Reference Uzun Jacobson, Inglesby and Khan30 ; most were available only through the websites of the organizations that developed them.

CONCLUSIONS

Methods and processes for assessment of country systems are an integral part of a holistic approach to assuring country emergency preparedness, including simulation exercises, after action reports and peer reviews.31 We conclude, however, that few of the existing tools satisfy all or most of the requirements for utility and effectiveness discussed previously. There is a continuing need for further improvement in tools available for countries’ assessment of their preparedness for public health emergencies. Existing tools could be revised with critical review of the validity of their assessment elements and indicators, and availability in more user-friendly electronic format with analytical and reporting modalities. New tools could be developed de novo at country and supranational level based on both a country’s needs and best available evidence relating to the validity of its assessment elements and indicators.

The paucity of applied emergency response systems research remains a significant impediment to achieving these improvements. In particular, the elements of the preparedness system that are valid indicators of actual response capability remain poorly understood. Reporting and critical review of user experience of all of the different means of evaluating country preparedness should contribute to this goal.31

Acknowledgments

This review was part of the ECDC-funded project, “Develop tools, templates and guidance to support the self-assessment by EU member states of their core capacities for preparedness and response planning, in line with the International Health Regulations.” The authors thank all of the experts who participated in the project from Public Health England, United Kingdom; Robert Koch Institute, Germany; Institute of Health Carlos III, Spain; and Italian National Institute of Health, in particular: Andreas Gilsdorf, Juliane Seidel, Maria an der Heiden, Maria Grazia Dente, Silvia Declich, Cristina Bojo, Cristina Fraga, and Virginia Jiménez.

Financial Support

The study was funded by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ Contributions

MH researched the literature and reviewed the tools; RCP researched the literature and reviewed the results; PR and GF were study investigator and commissioner, respectively; MH and GF wrote the manuscript; and ST, PR, UR, RCP, and MC critically reviewed the manuscript.