Introduction: Constructs and Constructs

In an age of intersectionality what could possibly motivate a defense of the old, vulgar position of class reductionism? In particular, what is left of the claim that “race can be explained by class?”Footnote 1 It depends on what we mean by “explained.” It also depends on what we mean by race as an explanandum and class as an explanans. Barbara and Karen Fields (Reference Fields and Fields2012) reject biological definitions and argue that race is “not even an idea (like the speed of light or the value of π) that can be plausibly imagined to live an external life of its own. Race is not an idea but an ideology” (p. 121). They reference the standard starting place in these debates—the claim that race is a social construct—and accept that claim as consistent with their own definition, but they also believe the standard definition to be “trite” and a “truism” (pp. 100, 157). In our view, the standard constructivist claim is neither trite nor a truism, but it is ambiguous.

Indeed, the term “social construct” leaves ambiguous what kind of construct race is supposed to be. There are constructs and then there are constructs: one type suggests that the phenomenon in question is purely a product of our mental bookkeeping (Tversky and Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1986); once we change the categories in our heads there will be no earthly residue. History would still have a long shadow, but if we pressed the reset button on history and changed our mental categories, race is the kind of construct that would disappear from the world. Call these belief-dependent constructs. Consistent with the Fieldses’ definition, race is a belief-dependent construct.

Is social class also a construct? Surely any social scientist worth their salt would insist it must be. But is it a social construct in the way race is a social construct? It cannot be the same kind of animal. No amount of rejiggering of our mental categories pertaining to social class would undo their empirical content. Even after some thoroughgoing reconceptualization and a full master cleanse of the mind, there would continue to be people with low or high educational attainment, poor or excellent housing conditions, low or high income, and varying levels of access to the means of subsistence and control over the means of production. Class exists independently of our beliefs, in other words, but race does not. Of course, education, housing, income, and the distribution of productive assets are all products of the structures, institutions, and the overall social organization of society, and this is the sense in which class is a social construct. Class is therefore best understood as a structure-dependent construct.Footnote 2

Distinguishing between structure-dependent and belief-dependent constructs sheds much-needed light on the conceptualization of both race and class and the relation between them. How then should we think about the relationship between belief-dependent constructs and structure-dependent constructs? Our argument is that the explanatory arrow must run from the latter to the former. We follow G. A. Cohen’s (1978) defense of the explanatory primacy of structure-dependent constructs. Cohen starts with a philosophical-anthropological claim: humans are roughly rational actors who seek to solve problems imposed by scarcity. This problem-solving results in the unidirectional development of technology—or productive forces, in his language—over time: when we find better ways of doing things, we typically retain them. As technology develops, transformations in how people relate to those productive forces follow as older economic relations become incompatible with the efficient development of the productive forces.Footnote 3 These transformations of economic relations—how people relate to productive forces—give rise to transformations in the “superstructure” (belief-dependent constructs like constitutions or the legal system or the concept of race) which function to stabilize the relations.Footnote 4

But why not have it the other way around? Could ideology be a prime mover? Begin the story again with our philosophical anthropology: humans are rational problem solvers trapped in a context of scarcity. Perhaps people who want things develop various ideas about how to obtain those things—including ideas about who is trustworthy, who is deserving, who can be allied with, and so on. These ideas (belief-dependent constructs) lead people to build the actual institutions that then produce material patterns of inequality (structure-dependent constructs). What justification is there, then, for the generic claim that belief-dependent constructs will be explained by structure-dependent constructs? Notice first that both stories start with a human response to material need (“people who want things”). But what’s more, in the second story the ideas themselves emerge out of existing distributions of resources. That is, they develop under specific material circumstances: the structural condition of material scarcity and unmet human need. Were the circumstances different, so would be the ideas about how to make a living: a Garden of Eden would generate very different strategies for obtaining goods, alliance making, and so on. On Cohen’s view, there is a causal asymmetry between belief-dependent constructs, such as race, and structure-dependent constructs, such as class, in which the latter take explanatory priority.

Following the Fieldses, then, race must be understood as an effect, a result of other social phenomena. In particular, it is the product of some kind of exclusion which usually has a key material dimension; that is to say, social class. By contrast, the attempt to build structure into the very concept of race itself (i.e., Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva1997) necessarily ends up reifying race (Loveman Reference Loveman1999). It suffers from the fallacy of “analytic groupism,” the treatment of groups as “fundamental units of social analysis” rather than belief-dependent constructs to be explained (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2002, p. 164; see also Emirbayer and Desmond, Reference Emirbayer and Desmond2012). Mara Loveman was right to criticize the essentialism underlying Bonilla-Silva’s “structural interpretation” of race, but her alternative theory of social closure lacks the courage of its convictions. What exactly is being closed off? If we have in our heads some kind of material exclusion then we are class reductionists by another name. More generally, if we wish to avoid “groupism,” then the group must rest on a structure that lies elsewhere; we must perform a reduction of one kind or another. To invert Frank Parkin’s (Reference Parkin1979) dictum, inside every Weberian is a class reductionist struggling to get out. This article is an attempt to clarify, refine, and denote the limits to this line of reasoning. An upshot is that class reductionism operates as a powerful antidote against race essentialism.

Class reductionism has an immediate implication: race must be understood as determined and not in the first instance a determinant. Failure to acknowledge this, forces one to concede the first principle of racism—that race is an autonomous cause, a prime mover.Footnote 5 Sometimes sociologists argue that race is not biological, but still an explanans, still somehow a determinant. To be sure, in statistical models, race often turns out to be a significant independent variable on its own, even when controlling for class or a race-class interaction term. But this forces us to ask exactly how race operates in our explanatory model of the world, how it stands on its own feet. Conflating statistical and explanatory models can unwittingly lead the social scientist right back to racial ideology. Notice that both alternatives to class reductionism—race reductionism and conceptualizing race and class as co-equal determinants—require us to assign fundamental causal power to race per se, not in a statistical sense, but in an explanatory one. The attempt to build structure into race falls into this trap, resting ultimately on the premise of race essentialism.Footnote 6

On the other hand, class is a concept of a different stripe. For one thing, social scientists today are hardly in any danger of “class essentialism,” as the concept of class is defined from the outset in terms of economic and social relationships (i.e., Calnitsky Reference David2018; Scott Reference Scott2014; Wright Reference Wright1997). It does not invoke nature or biology, or even beliefs, as theories of race do. Indeed, in an era where meritocracy and political equality form the ubiquitous background ideology, it is not entirely clear what “class essentialism” could mean. Perhaps it is a kind of aristocratic sensibility suggesting that nobles were born to be nobles, and serfs born to be serfs (“You can take the serf out of feudalism…”).Footnote 7 For instance, in the history of Russian serfdom, there was an aristocratic belief that serfs had black bones (Kolchin Reference Kolchin1987). This form of class essentialism is interesting because it turns out to be race.

This article begins with the claim that if we reject biological and other essentialist definitions, then it is reasonable to define “race” in ideological terms. It is a “symbolic category” (Desmond and Emirbayer, Reference Desmond and Emirbayer2009) and fundamentally an ascriptive category because one’s race depends, practically speaking, on what other people think it is.Footnote 8 It is, in a word, a belief-dependent construct. By contrast, class, a structure-dependent construct, has a meaningful non-ideological referent—namely, the social organization of material inequality. We can then say that ideology is something to be explained, and the explanation of ideology—if it is to be non-random and non-biological—must rely in some way on social institutions. Thus, belief-dependent constructs should, as a general rule, be explained by structure-dependent constructs. This may have been what Arthur Stinchcombe meant to convey when he declared, perhaps only half-seriously, that “sociology has only one independent variable, class” (Quotation in Wright Reference Wright1979, p. 1).

Crucially, however, none of this suggests that race has no empirical effects. After all, ideology can have its own effects, even if it has ultimate causes itself.Footnote 9 This is what it means to describe a system as recursive. Moreover, the class-functional explanation of race—which this article goes on to describe and, in part, to defend—is precisely one that explains race on the basis of its effects. In particular, we draw attention to the critical role race plays in the stability of capitalist class relations. The notion of a class reductionist case for the centrality of race sounds like a contradiction in terms, but it’s not. To see why, we need to clarify the nature of functionalist explanation. Race is not in this view epiphenomenal; it is not a mask, hiding real economic relationships (Miles Reference Miles1984). Rather, it has causal effects of its own, which is crucial in our account.

Sometimes the recognition that race has its own causal effects is taken as evidence that it ought to be considered, in our terms, a structure-dependent construct. For example, along these lines, Bonilla-Silva’s (Reference Bonilla-Silva1997) “structural interpretation” points to processes of racialization that acquire “autonomy” and have “pertinent effects” which imply “that the phenomenon which is coded as racism and is regarded as a free-floating ideology…constitutes the racial structure of a society” (pp. 469-470). Because race has causal effects, and because he presumes that ideologies are “free-floating,” Bonilla-Silva regards race as a structure-dependent construct and not a belief-dependent construct. This we believe is precisely the kind of mistake that is remedied in our interpretation. Again, in functionalist explanations variables can have “pertinent effects” and still themselves be explained by other things, and belief-dependent constructs are explicable in terms of structure-dependent constructs.

Nowadays, when someone calls attention to functionalism in an argument it is taken for granted as a critique, sometimes a fatal blow. Indeed, we grant that (1) most of the arguments conjecturing that race is a necessary condition for capitalist class relations are indeed functionalist, and (2) most of those functionalist arguments fail because they lack a mechanism to support the conjecture.

Although functionalism is much maligned, we argue that there are ways to defend it, and indeed this is precisely what must be done if we are to explain race by virtue of its stabilizing effects on the class structure of society. This kind of explanation goes to the heart of the interaction between race and class, even if it is rarely recognized as such. In this connection it is worth pointing out the political significance of the class functionalist explanation of race. The functionalist argument locates the ultimate causes of racism in the inherent instability of capitalist class relations, which in turn tend to “select” racism on account of the latter’s stabilizing effects on those relations. If this account is true, and if we wish to avoid finding replacement stabilizers, then a thoroughgoing antiracism needs to direct attention to the class structure itself, and anticapitalism needs to attend to the effects of race.

In order to be clear about what we are not arguing, in the next section we provide a typology of the different species of class reduction offered in the literature and point out which kinds of class reductionism are unacceptable and which kinds can be defended. Specifically, we reject class reductionisms that suggest (1) class to be a more fundamental form of identity than race; (2) class to be of greater normative importance than race; and (3) race to be an epiphenomenon of class, without independent effects. However, we do accept one class reduction that establishes race as causally dependent on class; in particular, we defend the view that race is functionally explained by class.Footnote 10 In sections three and four we make clear the concept of functional explanation and spell out its role in these debates. In particular, we show that none of these arguments imply that race or racism is inherently insurmountable inside of capitalist class relations. Capitalism can explain racism without requiring it as a permanent feature. We close by outlining the limits to our argument, clarifying where our class reductionism can and cannot be defended.

Species of Class Reductionism

Class reductionism comes in different shapes and sizes—some are defensible in whole or part, and others must be rejected totally. Here we review various genres of class reductionism in order to more clearly bring into view a defensible version.

Class is a more fundamental basis of identity than race

This variant of class reductionism holds that because a person’s class location fundamentally shapes their immediate material interests, it therefore is more central to the formation of their subjectivity. We do not deny that there is a relationship between one’s location in the structure of class relations and the social identity that one tends to adopt, but it is difficult to defend the claim that in general class is more important than race in this regard.

Our claim—that racism is a belief-dependent construct, and that belief-dependent constructs are determined ultimately by structure-dependent constructs—has nothing whatsoever to do with a claim about what identities may become important for people in how they make sense of their experiences, construct their biographies and self-image, or decide to participate in civic life. People may well hook into a racial identity over a class identity. For that matter, one may adopt a primary identity on the basis of their occupation, their sexual orientation, their religious beliefs, or their favorite hobby.

An individual’s identity is determined by an extraordinarily varied set of concrete determinants, including discursive factors, in a highly complex social world. The emergence of a class as a collective agent, in which people are mobilized on the basis of their allegiance to a class identity, is not given automatically by the objective structure of class relations. Adam Przeworski (Reference Przeworski1985) puts it this way:

Collective identity, group solidarity, and political commitments are continually forged, destroyed, and molded anew in the course of conflicts among organized collective actors, such as parties, unions, corporations, churches, schools, or armies. The strategies of these competitors determine as their cumulative effect the relative importance of the potential social cleavages…. Thus sometimes religion and sometimes language, sometimes class and at other times individual self-interest become the dominant motivational forces of individual behavior (p. 121).

The problem of how classes become historical actors is known as the problem of class formation (Hardin Reference Hardin1982; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1985; Wright Reference Wright1997); any a priori commitment to the notion that class identity is somehow more natural or fundamental than racial or any other identity elides this important question entirely. Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2002) makes the same point when he writes that “by invoking groups, [political entrepreneurs] seek to evoke them, summon them, call them into being” (p. 166). The identities people actually adopt depend powerfully on the influence of these “political entrepreneurs,” rather than following straightforwardly from their structural position.

It is true that socialist parties want to activate people’s class identities and appeal to people’s material interests—it is in this way that left parties, like all other parties, are always in the business of doing identity politics. But if they are unable to activate those identities, and workers are instead organized as, say, Catholics, then there simply exists no higher value, no meta-argument suggesting that those latter identities are somehow wrong. There is no law asserting that spiritual needs are less meaningful than material ones. This is what usually underlies critiques of “false consciousness.” Your “consciousness” might be false if you believe a descriptive fact or empirical claim that does not hold, but not because you absorb some non-class group identity (for discussions, see Boudon Reference Boudon1989; Larraín Reference Larraín1979; and Rosen Reference Rosen2016). These kinds of arguments, littered throughout the history of the Left, must be abandoned wholesale.

To repeat, it is also true that class structures impose certain experiences on people that imply systematic links to identity (Chibber Reference Chibber2017). Workers must adopt certain strategies to subsist and thrive: most fundamentally, they must sell their labor-power. In practical terms, they cannot walk away from the labor market in the way one can walk away from a church, for instance. This structural fact might have implications for identity even if the actual relationship is very loose.Footnote 11

But even if human beings must first satisfy our material needs, those needs will often be met through non-class social groups which may shape people’s self-constructions. More importantly, it is a brute empirical fact that some identities are more salient than others in various contexts and that is the end of the story. Different sexual identities emerged, for instance, in contexts that were impacted causally by material factors, but the causal asymmetry is irrelevant to the question. The fact of the matter is that sexual identities became salient for many people. There is no good reason in our view to say that one or another identity is more “fundamental” or “basic.”Footnote 12 When it comes to identity, there is no deeper fact to appeal to than a person’s subjective orientation. Identities are objective facts about subjective states. Your feelings are the facts and whether race, class, or something else entirely inspires identity is an empirical matter.

Class takes moral priority over race as a form of oppression

This argument will be familiar to those operating in certain radical or activist milieus. In this view, exploitative class relations are more directly responsible for human suffering than racism and should therefore be prioritized in the development of critical theory—and, by extension, in the formation of movements to oppose and dismantle oppressive systems. Anti-racism as a theoretical and practical program, even if well-intentioned, is in fact an unproductive distraction from the fundamental problem: class relations based on domination and exploitation. Class relations take moral and strategic priority, so the argument goes, not because racism is unimportant or exaggerated, but because racism is merely a side effect of, or even a misleading name for, class inequality. From this perspective, anti-racism confuses the enemy’s silhouette for its body. Adolph Reed has recently made arguments to this effect with regard to scholars who emphasize anti-racism. In the context of a discussion on patterns of police brutality in the United States, he argues that “antiracist politics is the left wing of neoliberalism in that its sole metric of social justice is opposition to disparity in the distribution of goods and bads in the society, an ideal that naturalizes the outcomes of capitalist market forces so long as they are equitable along racial (and other identitarian) lines” (Reed Reference Reed2016; see also Reed Reference Reed2013). In this view, insistence on racial disparities conceals the truly fundamental matter of class relations.

One can grant Reed’s point without concluding that class, as a rule, ought to take moral priority over race. First, if one rejects the theoretical claim above—that racism is an epiphenomenon of class relations—as we do, the conclusion that racism is therefore morally secondary has little basis. As we argue below, while racism can be explained by capitalist class relations, it is not merely a side-effect but a crucial buttress of those relations. This means that it cannot be treated as a distraction from the problem of class oppression, but rather should be seen as an integral part of it.

Second, the solitary goal of making life outcomes proportional along racial lines is desirable, from our point of view, even if we change nothing else about the world. It is not obvious to us that, in general, reducing class inequality ought to take moral priority over reducing racial inequality. An example may be clarifying. Is it a greater moral bad to be excluded from a country club on the basis of insufficient income rather than on the basis of race? If a country club is too inconsequential, what about a country? Canada excludes migrants on class lines, but Israel excludes on ethno-racial lines and the latter exclusion might take moral priority. Our intuition is that the details of the case in question will determine our moral attitudes, but it is not straightforward that either race or class command moral priority in some highly generalizable sense. In any event, the form of class reductionism we defend does not rest on any claims about moral priority.

Racism is causally dependent on class oppression

All versions of the class reductionist argument for racism, including one that we defend, make some version of the claim that racism is causally dependent on some aspect of class relations. This basic position can be found across otherwise quite diverse arguments about the relationship of race to class, including those that cast themselves as non-reductionist. Indeed, the race/class debate is not generally one about whether racism is based in class relations, but how.

One argument is that racism is a more or less deliberate rationalization of particular class relations concocted by elites in order to provide moral cover for arrangements that would otherwise be intolerably contrary to colonial societies’ liberal beliefs about themselves. Karen and Barbara Fields (Reference Fields and Fields2012) for instance suggest the ideology of race as a necessary solution to the contradiction of enslavement in a nation that based itself on radical notions of equality. Ira Berlin (Reference Berlin1998) and others have argued that racism was based in slavery and not the other way around, and cite Bacon’s Rebellion as a turning point where elites took the initiative in constructing race for the purpose of foiling future attempts by Black and White settlers to form solidarities. Theodore Allen (Reference Allen1997) likewise argues that the “white race” was invented as “a ruling class…social-control mechanism” (p. x). Another argument is that racism developed largely as a popular phenomenon resulting from the psychic tensions of recently proletarianized Whites who, with both envy and contempt, falsely perceived Blacks to be living lives free of the new industrial discipline (Roediger Reference Roediger1991), or who perceived a threat of labor market competition from Blacks, enslaved or free (Bonacich Reference Bonacich1972, Reference Bonacich1976). Historical arguments for the basis of racism in class oppression broadly conceived are thus widespread, and there is considerable evidence for the claim that racism is causally dependent on class oppression in some way or another, or in different ways at different times.

There is good reason that scholars with such different theoretical perspectives should converge on some kind of reduction: the alternative to the reductionist view is that racism is simply a more or less predictable outcome of the interaction between racial groups, the existence of which is given by nature. In sociology, Robert Park is the most prominent representative of this primordialist view. He writes:

The races of mankind seem to have had their origin at a time when man, like all other living creatures, lived in immediate dependence upon the natural resources. Under pressure of the food quest, man, like the other animals, was constantly urged to roam further afield…in search of some niche or coign of vantage…. It was, presumably, in the security of these widely dispersed niches that man developed, by natural selection and inbreeding, those special physical and cultural traits that characterize the different racial stocks (Park Reference Park1950, p. 7).

Here, race is a natural consequence of the geographical isolation of human subgroups, which over time leads to sharp cultural and, crucially, physical distinctions. As for the emergence of racial prejudice and oppression, this too is a natural outcome of relations between given racial groups. Race prejudice is a result of “deep-seated…impulses” and “may be regarded as a spontaneous, more or less instinctive, defense-reaction…. [We] may regard caste, or even slavery, as one of those accommodations through which the race problem found a natural solution” (Park Reference Park1921, p. 620). It should be noted that the implications of such an explanation are rather bleak. If, as Park suggests, the formation of rigid caste arrangements is a “natural solution” to the problem of race relations, then, as Oliver Cox (Reference Cox1959) says, we “inevitably [come] to the end of a blind alley: that the caste system remains intact so long as the Negro remains colored” (p. 517).

Such naturalist explanations of race are empirically unconvincing given the much more recent emergence of the race concept and race discourses in the historical record.Footnote 13 This is why historians and other scholars often make arguments that are ultimately class reductionist. They insist that they are not rendering reductionist interpretations, but they are: it is just that their reductionisms are non-vulgar. This is as it should be, for the alternative, primordialist argument is not only unconvincing, but depends on a crucial premise of racism: that there really are races given by nature that distinguish human groups from one another and that this is the fundamental basis of “race relations.” If we argue, following Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva1997; see also Elias and Feagin, Reference Elias and Feagin2016) that race has a structure unto itself—and not that it is a product of some exclusion that usually has a material dimension—then that structure must have foundations in the group itself. This is garden-variety “groupism,” and it is why every “structural interpretation” has Parkian primordialism at its core. If race does not have an inner structure, then we must find ways to reduce it to something else.

Race and capitalism, or: Which reductionism?

It is possible to argue, as Park does, that racism predates European colonial expansion, and that racism is not explained by capitalist class relations, without relying on his strong primordialism? A more defensible and provocative version of the argument to this effect is found in Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism (1983). This book is often considered to be a repudiation of class reductionism, and even a form of race reductionism. But Robinson’s account can be read as a class reduction of a different sort.

Robinson argues that racism is a much older feature of Western civilization than capitalism and cannot therefore be explained by the historical development of the latter. In the Middle Ages, the nobility differentiated themselves from those in the lower orders, insisting that their higher status followed from their better hereditary stock: noblemen descended from the Trojan heroes, while the peasants descended from Ham, the cursed son of Noah (Hertz Reference Hertz1970; cited in Robinson Reference Robinson1983). Nascent bourgeoisies, developing in the interstices of the respective territorial states on which they depended, with their own linguistic and cultural characteristics, emphasized their differences with competing bourgeoisies and insisted upon the supremacy of their own “national” section of that international class. At the same time, economic and military demand for manpower spread European migrant populations of highly varied linguistic and cultural backgrounds across the continent into ethnically structured divisions of labor. The practice of racial differentiation therefore emerged as an ideological tool of these ruling classes, who used it to justify and cement their position vis-à-vis the laboring classes of their own dominion and their claims to dominance over the ruling classes of other dominions. Thus, when capitalism emerged in Europe it was already racialized—the same practices of differentiation and division which degraded the lower orders and colonized peoples of Europe were refined and extended to those of Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

For our purposes, it is important to note that this argument identifies racism as rooted in class relations, differing from the other arguments only in the claims about which class relations are relevant to the explanation. For Robinson, racism emerged to rationalize pre-capitalist class relations; capitalism subsequently developed with race built in, inheriting and repurposing the practice of national-racial differentiation established in the European Middle Ages. The argument challenges explanations of racism rooted in capitalist class relations; however, pushing the causality to older class relations is no less class reductionist.

The basic claim that race is rooted in class relations, then, is broadly shared and contains within it a whole range of quite different specific claims. In the next two subsections, we contrast two versions of this argument that come to opposite conclusions about the relevance of race and racism and their connection to class relations. The first version is that racial oppression is an epiphenomenon of class relations. In this view, racial oppression does not have any actual effects in its own right, but is ephemeral, an illusion created by class arrangements. The second is that racial oppression has profoundly important effects that function to stabilize capitalism. The existence and tenacity of racism are explained by these effects. This kind of functional explanation is a subspecies of the view that racism is causally dependent on class. Ultimately, we reject the epiphenomenal position and spend the remainder of the article defending and clarifying the functional claim.

Racial oppression is an epiphenomenon of class relations

The first subspecies of the broader class reductionism, and an idea often mistaken for class reductionism generally, is the notion that race is merely an epiphenomenon, an inert byproduct, of class relations. In this view, race does not have any effects in its own right; what appear to be the effects of race really are the effects of class. Racial oppression is class oppression, misapprehended. Or, in the words of Robert Miles (Reference Miles1984), race is a “mask” concealing deeper economic relations (see also Miles Reference Miles1993).

Oliver Cromwell Cox’s classic study Caste, Class, and Race offers a sophisticated epiphenomenalist view. In fact, that monumental work makes at various times both epiphenomenal and functional claims about racism. While we lay out here the epiphenomenal aspects of the argument in order to reject them, Caste, Class, and Race is a first-rate work on the sociology of race and an early systematic example of what would later be called a social constructionist view of race, defining “races” not as naturally differentiated groups but as “simply any group of people that is generally believed to be, and generally accepted as, a race in any given area of ethnic competition” (Cox Reference Cox1959, p. 319; see also Reed Reference Reed2001). Cox overturned the sociological orthodoxy of race of the time. In particular, he rejected Park’s view that race is a natural result of the proximity of physically and culturally different human beings with a natural, inborn propensity to make a rather big deal about those differences. Against these tendencies, Cox developed an approach to race and race relations that specified their social-structural determinants, demonstrating the sense in which, as today’s standard boilerplate goes, race is a social construction. In our terms, Cox sought to describe the structure-dependent constructs underpinning the belief-dependent constructs. Thus, it was properly a sociological theory of race relations where the previous theories were not; indeed, the epiphenomenal view of race has more to recommend it than these alternatives.

The outlines of Cox’s argument should look familiar to students of the race/class debate, as it represents one of the strongest versions of the claim that race is reducible to capitalist class relations. In the early history of Europe’s colonial acquisitions in the Western Hemisphere, unfree labor—either slavery or indentured servitude—was quite normal, and unfree laborers could be of European, African, Indigenous American, or any other descent. Intense competition between the colonial powers for the exploitation of the New World led to acute labor shortages that could not be adequately met by European labor, which was therefore eclipsed by African slave labor in the British colonies and a combination of African and Indigenous slave labor in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies.

The basis for this enslavement was not an ancient feeling of racial antipathy, which at the time was only nascent. The “fact of crucial significance is that racial exploitation is merely one aspect of the problem of the proletarianization of labor, regardless of the color of the laborer,” and therefore “racial antagonism is essentially political-class conflict” (Cox Reference Cox1959, p. 333). What are misleadingly called race relations, then, are a moment of the proletarianization of labor in which “a whole people” is reduced to proletarians, rather than only a part, as was the case with whites, only a portion of whom are proletarianized (Cox Reference Cox1959, p. 344). The explicit ideologies we identify as racism only arise post hoc as a rationalization for the brutal forms of incorporation into the capitalist system that Indigenous and African people faced. The hypothesis is laid out in refreshingly clear terms: “[R]acial exploitation and race prejudice developed among Europeans with the rise of capitalism and nationalism, and…all racial antagonisms can be traced to the policies and attitudes of the leading capitalist people, the white people of Europe and North America” (Cox Reference Cox1959, p. 322). Aspects of this argument are confirmed by historians and theorists who do not necessarily go on to make the epiphenomenal claim, but Cox takes that final step when he argues that racism itself was nothing more than the ideological reflection of the emergence of race relations, which in turn was based in the labor requirements of capitalist expansion in Europe’s colonies.Footnote 14

The epiphenomenalist perspective has important implications for research. Little is gained in this view by studying racism per se, which could at best only illuminate the “opinions and philosophies” of racial ideologists (Cox Reference Cox1959, p. 482). At worst, an emphasis on race and racism actually distracts from the essential questions: the proletarianization of a people and the reproduction and geographical movements of the reserve army of labor. A research program focused on the problem of racism would be, in a word, idealist. To focus on racism is, again, to chase the shadow of capitalism.

We reject this view. Again, the epiphenomenalists are correct to locate the origins of modern race antagonism, to use Cox’s phrase, in the development of global capitalism and imperialism rather than in the European psyche. Yet the study of “opinions and philosophies”—ideology, belief-dependent constructs—can hardly be regarded as beside the point to the extent that they have pertinent effects on the perceptions, motivations, and actions of ordinary people and elites, and on the social organization of material inequality. One cannot study quantitative sociology and also maintain that racism is an ideological mirage without effects of its own. The independent statistical effects of race reported in every volume of every good sociology or social science journal demonstrate the effects of racist ideology.Footnote 15 If one grants, then, that race does have effects of its own, how might it be understood as causally dependent on class? This is the task of the functionalist explanation.

Racism is functionally explained by class relations

The functionalist argument explains racism by appealing to its stabilizing effects on class relations. Before elaborating our defense of the functionalist position, it is worth reviewing the foremost example of functionalist thinking in social theory. Perhaps the most influential functionalist argument for ideology in general, encompassing the ideology of race, comes from Louis Althusser. In his essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” (ISAs), Althusser adopts the orthodox Marxist base/superstructure metaphor when he posits that ISAs (read: institutions) and the ideologies corresponding to them can be explained by their function. In particular, ISAs ensure the willingness and capacity of workers to return to work, day in, day out, through “submission to the rules of the established order” (Althusser Reference Althusser2014, p. 236). Ideology—conveyed through churches, schools, the family, mass media, as well as more diffuse “discourses,” labeled collectively as ISAs—acclimatizes the working class to domination, and the ruling class to dominating.

Althusser does not mention the ideology of race, but we can take the step ourselves. The ideology of race, itself organized and reproduced in ISAs, plays this reproductive role for labor-power because it justifies the special oppression of one segment of the working class in the eyes of another, encourages White workers to identify with their White superiors, and compels Blacks to acquiesce to hyper-exploitation.Footnote 16 To be sure, the economic structure—the “base”—need not, on this view, determine every facet of the ideological superstructure (Cohen Reference Cohen2001). Nevertheless, the superstructure is determined “in the last instance” by the base, in that it is conditioned by the functional requirements of that base.

Ultimately, Althusser’s formula is unsatisfying because he forgets to provide any causal mechanism whatsoever. We are left with a vulgar, circular functionalism—capitalist social relations require stabilizing ideologies, and these ideologies spring forth from capitalist social relations. How exactly ideological beliefs come to glom onto social relations is totally unspecified.

Still, Althusser was onto something. If he had a method, it would be this: look for clues as to how systems are reproduced over time. This stands in contrast to historical analyses searching out the first instance of some phenomenon, as if that alone will unlock its secrets. Sometimes scholars trying to sort out race and class, including those mentioned above, look to the origins of racism in the United States and conclude that before, say, Bacon’s Rebellion, there were no races in the modern sense.Footnote 17 One might here pose a distinction between “historicist” class reductionism and “reproductive” class reductionism to highlight the difference between these kinds of historical arguments and the functionalist approach.

The reproductive class reductionism of the functionalist approach is superior, in our view, for two reasons. First, accounts that are only historically class reductionist tend to smuggle in an essentialized concept of race and grant it unjustified causal primacy—after the point of its emergence. We repeat Barbara Fields’ (Reference Fields and Fields2012) criticism: with historicist class reductionism, race, “having arisen historically…then ceases to be a historical phenomenon and becomes instead an external motor of history; according to the fatuous but widely repeated formula, it ‘takes on a life of its own.’ In other words, once historically acquired, race becomes hereditary” (pp. 120-21).

Second, the search for origins is simply not decisive for explanatory purposes, nor is it even required. If we wish to understand religion, for example, more important than locating the first religious person is locating the reasons religiosity is so durable. The first instance of any category is uninteresting if it does not shed light on its durability. An origin story can be useful for understanding the generative processes underlying race, but this is no universal law. That some division was at one point invented does not tell us whether or not it was sustained, nor why it was sustained. Thus, history is not enough and genealogical arguments will not suffice (Honderich Reference Honderich and Honderich1995).

But avoiding the genealogical fallacy does not imply that the past is irrelevant. Indeed, focusing on the social reproduction of group dynamics reveals what in history becomes institutionalized.Footnote 18 International comparisons of racial systems demonstrate the centrality of original conditions for explaining fine-grained variations in how racial categories are constructed and how racial inequalities are differently institutionalized (e.g., Frederickson Reference Frederickson1981; Marx Reference Marx1998; Wolfe Reference Wolfe2016). Nevertheless, if we wish to explain the existence and durability of race—inclusive of these international and historical variations—more important than pinpointing origins is accounting for the broad determinants of its social reproduction. This is where the functionalist argument for an ongoing reduction of race to class can play a more analytically useful role than a hunt for the ultimate class origin of race; it determines why the phenomenon, once established, will hold its place rather than dissolve.

Althusser posed functional relationships devoid of the necessary mechanisms that make them tick. In what follows, we wish to defend a functionalist explanation with the specification of mechanisms.

Parsons rehabilitated

In this section we explain how functionalist explanations work in general and in the next we apply this form of explanation to race in particular. First, however, we wish to motivate the investigation: how can we justify the defense of a functionalist explanation of race in light of the alternatives? Are the intentional explanations—that is, cases where the deliberate, goal-oriented actions of agents can sufficiently explain some intended effect—of Allen, Berlin, Bonacich, Roediger, and others not up to the task of explaining the race/class link? Each of these arguments is unique, and a full critique of all of them would take us too far afield. Nevertheless, we wish to establish that a functionalist explanation provides some considerable advantages over these other explanations. It is not that these other explanations are incorrect on their own terms: there are plenty of recorded instances of attempted divide-and-conquer tactics by employers, numerous interracial conflicts rooted in split labor market dynamics, clear demonstrations of allegiance to a White identity, and so on. Indeed, in the functionalist account elaborated below, we cede some ground to intentional mechanisms.

So, what can functionalism do for us? First, a successful functionalist account of race can explain its social reproduction, its astounding durability, with more simplicity and elegance. Total reliance on an intentional account would require us to find not only those agents in earlier periods who created and widened racial divides, but those agents at all times who intentionally and successfully keep racial division alive. For instance, for any version of the intentional divide-and-conquer argument to work not only as an account of the origins of race, but of the persistence of race, we would have to find ongoing evidence that (1) capitalists (or their agents) indeed engage in such behavior; that (2) they do so with the specific aim to produce racial division; and that (3) they are good at what they do, in that the tactic really does produce the desired result. This last point will reappear below in our explanation of functionalism: intentional accounts can only tell us about someone’s attempt to, say, divide a group. This does not ensure that the intended effect is successful. Intentional explanations require that history’s racists always be shrewd strategists rather than incompetent bunglers. By contrast, as we show below, functionalist accounts rest on objective effects, irrespective of the intentions of agents.

Secondly, the unintentional character of a functional explanation corresponds to observed features of race in American life. Phenomena such as “racial inequality without racism” (DiTomaso Reference DiTomaso2013) or “racism without racists” (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2009) depend on unintentional reproduction processes. This is not to exclude the possibility of groups or influential individuals who do intentionally seek to reinforce racism on account of ideological commitments or the prospect of personal gain. But an implication of the notion of unintentional reproduction processes is that racial inequality would remain even if such actors became weak or disappeared.

Third, when you have outcomes that are durable, widespread, and evident across long periods of time with a changing cast of actors inside different kinds of institutions, it is reasonable to look for functionalist selection mechanisms. This pattern holds with the cases we explore below.

Finally, it is worth noticing again the political implications of a functionalist account vis-à-vis the others. If race is reproduced mainly through the intentional actions of powerful groups, in the manner of a divide-and-conquer explanation, then activist strategies for combating racism might emphasize vigorous civil rights law enforcement to catch employers in the act—in other words, just have stronger enforcement of the “rules of the game” of labor markets. And straightforward enforcement might entirely solve the problem because nothing in the intentional explanation requires those groups to be successful in their efforts. If, however, race is reproduced mainly through complex unintentional processes rooted in the rules of the game, more ambitious policy might be necessary to change the game itself. If race can be functionally explained, system-wide strategies for countering it need to be on the table. It is in this respect that paying serious attention to the mechanisms of social reproduction of oppressive structures and institutions is central to the project of an emancipatory social science (Wright Reference Wright2010).

Now, how do functional explanations work? How is it possible to explain something by appealing not to its causes but to its effects on some other thing? There is little doubt that plenty of functional explanations offered in sociology are facile at best, some doing scarcely better than Dr. Pangloss’s claim that his nose exists to hold up his spectacles (Gould and Lewontin, Reference Gould and Lewontin1979). If functional explanations in the history of sociology are not entirely Panglossian they often do have a mystical or ambiguous character. This is the legacy of Talcott Parsons; but Parsons merits rehabilitation.

One of the key problems is that theorists sometimes seem to believe that once they show that X has beneficial effects for Y, the work of explanation is done. For example, Lewis Coser was pilloried by Jon Elster for offering such an ambiguous case of beneficial effects: he argued that “conflict within and between bureaucratic structures provides the means for avoiding the ossification and ritualism which threatens their form of organization” (Coser cited in Elster Reference Elster1983, p. 59). The phrasing “provides the means for avoiding” is a good way to hedge on the claim. Coser was a critic of Parsons, but he replicated the ambiguity of Parsonian functionalism. Is conflict within and between bureaucracies explained by that effect? Did some person intentionally design bureaucracies that way? Was it dumb luck?

G. A. Cohen’s (Reference Cohen2001) distinction between functional description and functional explanation is helpful: We can grant that bureaucracy does indeed produce the stated beneficial effects (functional description) without insisting that it exists because of those effects (functional explanation). Thus, Coser gives us little to explain how the good fit between the feature (conflict) and the structure (bureaucracy) came about. Hyperfunctionalists observe benefits and automatically posit unwarranted explanations. Sunshine on John Denver’s shoulders made him happy (functional description), but that does not explain it (functional explanation). Indeed, it is always tempting to dodge the hard work of finding a causal mechanism underlying functional explanations (Cohen Reference Cohen1980, Reference Cohen1982; Elster Reference Elster1980; Van Parijs Reference Van Parijs1982).

Elster proposes a strict set of criteria for an explanation to properly count as functional. For Elster (Reference Elster1980), “an institution or a behavioral pattern X is explained by its function Y for group Z if and only if: (1) Y is an effect of X; (2) Y is beneficial for Z; (3) Y is unintended by the actors producing X; (4) Y (or at least the causal relationship between X and Y) is unrecognized by the actors in Z; (5) Y maintains X by a causal feedback loop passing through Z” (p. 28). To cite the classic case, set X to some rule of thumb about levels of output used by firms in a market, Y to profit-maximization or competitiveness, and Z to the relevant firms. And voila! Shoe factories are big (have high output) because of their effects not their causes: bigness makes them more competitive. They are not big because their owners intentionally made them big. This would be a standard causal-cum-intentional explanation, but here the owners might be entirely clueless. Instead, they are big because bigness, by fluke, leads to competitiveness through economies of scale. There is a structural selection process that feeds back, selecting for the survival of big firms and failure of small ones.Footnote 19

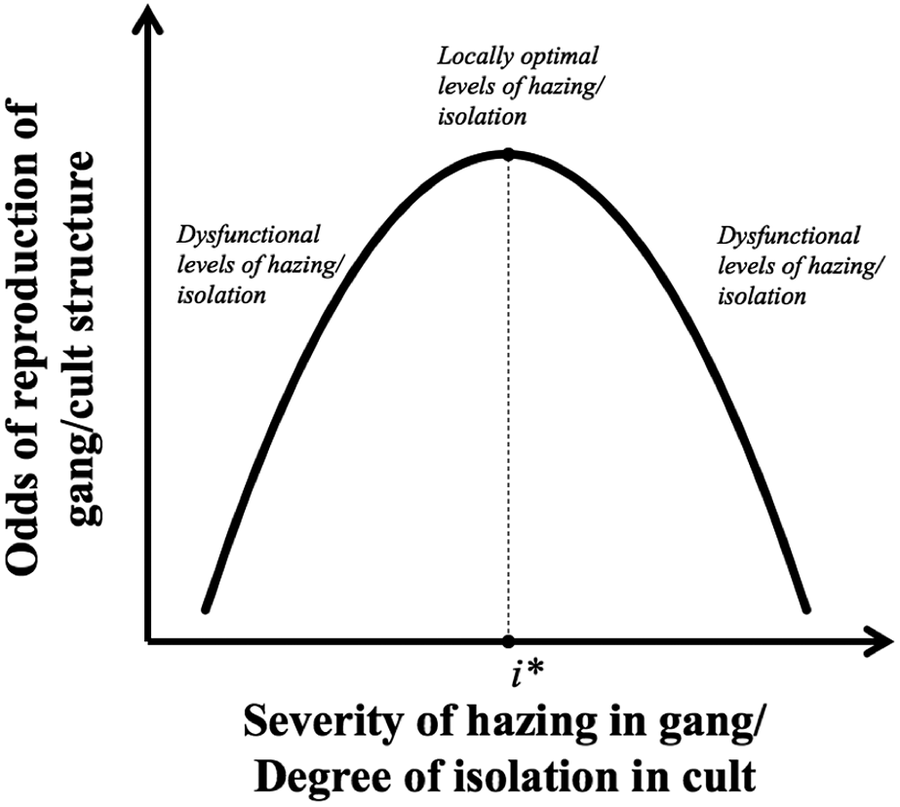

Elster believes further that very few examples meet the criteria above. To clarify the logic of the explanation and add some new examples to the repertoire, consider the concept of “local maximum.” Here, the way to construct a functional explanation is as follows: Taking a given context, a local environment, for granted, we can ask which traits or features best increase the chances of reproducing some structure. For example, certain practices of cults or gangs can be understood as local maxima given certain contexts. They can be seen, in other words, as “evolutionary attractors” (Van Parijs Reference Van Parijs1981, Reference Van Parijs, Callebaut and Pinxten1987). Why is hazing in gangs, fraternities, military units, sports teams and so on such a regular feature of those structures? The functional explanation says that hazing exists (X) because of its beneficial effects for the group (Z); namely, it improves solidarity and group cohesion (Y). Perhaps this is because experiencing a painful or costly event increases one’s conformity to the group, and those groups with more cohesion are more likely to survive over time. Groups with too little hazing, shown on the left-hand side of Figure 1, will then have lower chances of social reproduction than those with optimal hazing levels, denoted by i*. Moreover, groups with severe levels of hazing also hurt their relative chances of social reproduction, as those on the right side of the curve have levels of abuse that are high enough to either dissuade potential joiners or cause excessive rates of attrition.

Fig. 1. Functional dynamics with a local maximum.

A similar explanation can be applied to certain stable features of cults. Why do so many otherwise heterogeneous cult groups force members to cut social ties to family and outside friends? The functional explanation says that the isolationist practice (X) of the cult (Z) can be explained by its effects: cutting ties has the objective effect of reducing the possible exit strategies of members and increases the group’s survival chances (Y). On the left-hand side, those cult-like groups that do not force isolation on members undermine indoctrination because the inflow of external ideas and connections to outsiders who frown on cultish practices continually weaken the cohesion of the group. This gives them relatively low odds of stability over time. On the right-hand side, those cult-like groups with too much isolation from the rest of society find it impossible to draw in new recruits, and they too have relatively low reproduction chances. Thus, an optimal level of cutting ties—the function—is “fit” to the structure. Isolation is explained by its effects.

There is a wide range of other examples. The practice of tithing can be explained by its effects: tithing (X) in religious groups (Z) might be explained by how it furnishes the material resources all organizations require (Y) to survive over time. The financing of political parties might be similarly explained. Russell Hardin (Reference Hardin1980) offers a functional explanation of growing bureaucracy on the basis of its benefits for incumbent politicians: more bureaucracy (X) means more problems for voters, and more complaints to congressmen (Z), who get re-elected because they are best suited to understand and respond to those complaints (Y). They are better “fit” to the environment, to the structure. But this also means that they have less time for legislative work, which gets pushed onto the bureaucracy, thereby expanding.

We are now in a position to defend the honor of Lewis Coser against Elster’s broadsides: Conflict within bureaucratic structures may in fact have the objective effect of reducing ossification, even if no one intended it to be so. In that case, those structures may have relatively high reproduction odds and their features will be explained by their effects, functionally.

These examples make use of selection mechanisms and a story in which certain institutions survive and others, lacking certain features, fail. Organizations and institutions often compete for members, adherents, and supporters, and the functional-evolutionary arguments work well in those cases. Should functional explanations be relegated to meso-level organizations and micro-level actors that exist in a long-term semi-competitive environment? We can legitimately explain features of organizations and actors by appealing to fits onto structures. But what can we say about the macro-level? What about whole societies? Applying functionalism to race and racism requires us to make this analytical move.

Parsons expanded

If we wish to apply this kind of explanation to racism in America, we must ask the following: are there sufficient similarities between whole systems and organizations to make similarly functional arguments? One approach would suggest we appeal to a counterfactual of other possible system-level organizations to provide an explanation. A second approach is to allow for some intentionality around the edges of the functional explanation, which means relaxing Elster’s third and fourth conditions. And as we will see, sometimes what appears to violate these conditions in fact does not.

To understand these two approaches, take another classic example in the literature, Malinowski’s analysis of the fishing rituals of Trobriand Islanders. In Constructing Social Theories, Arthur Stinchcombe (Reference Stinchcombe1968) used Malinowski’s case study to illustrate the nature of functional explanations. The puzzle is this: What explains the fact that the Islanders perform fishing rituals before fishing at sea, but not at the lagoon? Rituals exist because of their effects: they reduce fear. It is dangerous to fish at sea, but not in the lagoon, and whether or not it was intended, the rituals have the objective effect of reducing fear, thereby facilitating fishing, and locking the practice in place. Notice that this example does not work as nicely as the shoe factory or cult examples. It is missing the crucial selection process—the mechanism that “locks” the practice in place is ambiguous.

In the first approach, as noted above, we posit a counterfactual environment of roads not taken. Of course, there is a difference between a factual environment of competing organizations and a counterfactual environment of organizational roads not taken. We can, however, suppose that there were in fact multiple societies and surmise that those remaining are unique in that they all somehow stumbled upon mechanisms to get fishermen fishing. The non-surviving societies that failed to get fishermen fishing died infant deaths, changed their practices, joined the successful societies, or were conquered by them. But even if there were no alternative non-surviving societies, the one we observe survived because it overcame all existential threats. In this view, the reason the Islander practices exist is because they happened upon a solution to the fishing problem.

But this explanation is missing some realism. Although it violates Elster’s criteria, the second solution suggests it is reasonable to sprinkle in some intentionality. Perhaps after some trial-and-error process, someone noticed that certain practices did produce desirable effects: they really did get people into the dangerous seas. Once the effect was noticed (violating condition four), the practice was encouraged (violating condition three) because its beneficial effects became clear. Moreover, not doing so, it was observed, put the community at risk. Elster argues that the effects must be both unintended and unrecognized, but one generation might have recognized an effect that the next was ignorant of.Footnote 20 In the cult example, one member might have at some point understood the beneficial effects of social isolation, even if it became standard operating dogma for later generations. Here we temporarily relax Elster’s third and fourth conditions, but only to ultimately re-establish them.

In fact, the functional explanation can stand even with a stronger and more permanent role for intentional mechanisms. The crucial point for the functional argument is the objective effect, or what Cohen (Reference Cohen2001) calls a “dispositional fact” (p. 261). Without the effect of religious practices—that really do fortify the resolve of the fishermen—the community would be unsustainable. The practice (and therefore the community) will only exist if it has the effect that it has. And so, it is not unreasonable to say it is explained by its effects, even if it was intended. Of course, someone might have encouraged the religious practice with an intention to appeal to the gods rather than to produce the objective effect of getting people to fish with confidence—in which case we need not relax Elster’s criteria at all, and safeguard the purity of our functionalism.Footnote 21 And, as we will see, there are parallels here with race. But the functional explanation survives even if the objective effect was the intended one. Adding an intentional mechanism does not leave us with a pure intentional explanation; were there different effects, whatever the intent, the community and the practice may not survive. If someone encouraged an uninspiring or halfhearted religious ritual, it might lack the galvanizing effect that allows for the survival of the community. Intentions are insufficient: in the case of the uninspiring ritual, the intentional explanation would have nothing to explain. Intentional mechanisms work when they are compatible with real social processes—again, Cohen’s “dispositional facts”—and the functional requirements of the system.

Parsons applied

The functionalist explanation of racism has two ways to go. The first approach posits a series of counterfactual societies that did not have pervasive racism, were unstable, and did not survive. The total system that did in fact survive did so because of the stabilizing effects of its racism. Early forms of American capitalism were deeply hierarchical and exploitative, and stabilized because their working populations were sufficiently divided. This approach mimics the functional explanation of cult isolationism. The second approach embraces some degree of intentionality. It may turn out that functional explanations of racism at the system level really do require this kind of treatment. Perhaps it became clear to some shrewd and strategic capitalist that after Bacon’s Rebellion a mechanism for dividing Blacks and Whites would be required to stabilize capitalist exploitation. Once racial divisions were set in place, they had an objective effect of providing stability, which may or may not have been recognized over time by its beneficiaries. Sometimes orthodox Marxists emphasize that capitalists will deliberately conspire to fabricate racism as a mechanism of division, and Rhonda Williams (Reference Williams and Darity1993) has criticized arguments posing “divide-and-conquer” as an explicit strategy of capitalists (e.g., Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Edwards and Reich1982; Reich Reference Reich1978, Reference Reich1981; Roemer Reference Roemer1978, Reference Roemer1979). But the functionalist argument says that division may be an effect, whether or not it was actually intended by capitalists. This is one way to understand the role of racism in a functional explanation: it produces an objective effect of division that might be absent in the counterfactual world without race.

Although intentional mechanisms are compatible with a functional explanation, there are a few ways that capitalists may reproduce race—producing the objective effect of dividing workers—even if they have entirely different intentions, satisfying Elster’s stricter criteria. First, labor markets may reflect “tastes for discrimination” (Becker Reference Becker1957, p. 8). Capitalists or their managers may themselves be bigoted. But even if not, they may be motivated to discriminate by the perceived or actual bigotry of their White employees, who may react to the hiring of a non-White worker by withdrawing their labor—or their White customers, who may react by withdrawing their patronage. Second, capitalists or their agents, lacking cheap and detailed information about applicants, may engage in statistical discrimination—that is, rely on real or imagined racial group attributes as a proxy for the expected productivity of the worker. Even if they have no taste for discrimination and no reason to believe that their employees or their customers do, they may believe that the social harms suffered by racial minorities—deteriorating schools, poor public transportation, worse health outcomes, and so on—tend to make them, on average, more costly hires overall. They discriminate, in their mind, in the pursuit of the most efficient employees.Footnote 22 In either case, it was not their intention to “divide-and-conquer” or tap into the racism that undermines worker solidarity.

Even when that solidarity emerges, capitalism comes with an in-built kill switch. To the extent that interracial organizations of workers in some market or industry are successful in reducing or eliminating racial skill and income differentials, dampening intraclass competition, and clawing back a greater share of the surplus, capitalists (or portfolio managers simply looking for profitable investments) will tend to slow or withdraw their investment and redirect it to fields unencumbered by the demands of organized workers. In other words, workers in some firm, region, or industry may overcome the racial divide—only for the work to vanish a short time later, and their organization with it. This is another non-intentional process that operates, as Marx says, “behind the backs” of agents. The racial divide may therefore be robust to attempts to overcome it, not due to the intentional machinations of capitalists or White workers, but because ordinary capitalist competition threatens the material basis of interracial working-class projects to the very extent that they succeed.Footnote 23

Because it is not entirely specified above, it is worth elaborating on the mechanisms by which racism can produce stable, long-lasting divisions. The key mechanism behind the claim that a racially divided working class will undermine solidarity is rooted in familial and friendship relations. A working class that is divided, say, along lines of skill alone—where those skill boundaries do not correspond to race—will be one that more easily accepts the trade-offs required by solidarity.

Even if the average worker is better off under solidaristic conditions—say, because the average wage is higher—a more compressed wage distribution means that some individual workers will lose out. If kinship networks include members with skilled and unskilled workers (perhaps you are a skilled worker, but your children are unskilled workers), it is easier to accept the solidarity trade-off. If, on the other hand, skill lines hew tightly to racial lines, because race tells us whom we form families and friendships with, then skilled workers from the privileged racial group will have no familial and friendship bonds with unskilled workers, and thus solidarity becomes harder to forge. If skill and race correspond closely, and solidarity means that at least some skilled White workers will change places with unskilled Black workers, then the trade-off will be harder to traverse. Even if all workers, skilled and unskilled, would be better off on average (Reich Reference Reich1978, Reference Reich1981), navigating circumstances where some individuals will be worse off is harder when the kinship ties across the skill divide are absent.

Finally, to link the reproduction of racism to its functionality for capitalism it is crucial to argue that because racism makes it more difficult for workers to organize as a class against exploitation, capitalists keep more of the social surplus as profit, and the effect is greater capitalist stability.

To flesh out this theoretical account it’s important to point out another feature of functional explanations: they all assume the existence of a problem. There is a problem in the structure that some feature is meant to solve. As Marx wrote, in either hyperfunctionalist or hyperbolic manner, “mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve” (Reference Marx1970, p. 21). The problem of the cult is social cohesion, and isolation is the solution. The problem for the Trobriand Islanders is the forbidding sea, and the stirring ritual is the solution. In arguments submitting that racism exists because it stabilizes capitalism, there is a usually unstated premise that capitalism on its own is inherently unstable, due in large part to inequality and exploitation. Is this a persuasive starting point?

Adam Przeworski (Reference Przeworski1985) suggests that capitalist growth provides its own stability. Steady increases in standards of living generate the consent that solves the problem of instability and provides social equilibration (see also Bowles and Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis1990; Burawoy and Wright, Reference Burawoy and Wright1990; Raff and Summers, Reference Raff and Summers1987; Roemer Reference Roemer1990). This argument might be persuasive for the extraordinary period of postwar growth, but we might not want to fix it as a stylized fact about capitalism. Indeed, we can point to long stretches of capitalist history during which living standards increased little for the modal citizen, and widespread misery (or relative deprivation) might have undermined capitalist stability. If we think about periods characterized by poverty and uncertainty for a non-trivial portion of the population, which is to say typical periods of the history of capitalism, we can certainly imagine that a divided working class would provide better system-level stability than a united one. It is possible to imagine then that when racist solutions were discovered, they endured because of their beneficial effects.

But if we really do see racism as a solution to the problem of instability, there is no reason to be wedded to the claim that racism is an intrinsic fact of capitalism. If racism sometimes solves the problem of capitalist instability, growth solves it equally well. From this perspective, capitalist economies have at least two problem solvers, growth and racism. The former makes people content; the latter divides the discontented.

With the question framed in this way, racism is itself best understood as one manifestation of the broader theoretical category of social division (see Banton Reference Banton1983, Reference Banton1998; Carling Reference Carling1991). We can imagine other ways to divide the working class: they might be divided along sectoral or regional lines, but more straightforwardly, workers can be divided by a hundred and one free-rider problems (Elster Reference Elster1985; Hardin Reference Hardin1982, Reference Hardin2001; Offe and Wiesenthal, Reference Offe and Wiesenthal1980; Oliver and Marwell, Reference Oliver and Marwell1993). It is not hard to imagine circumstances where workers are (1) unhappy, and (2) undivided by race, but consistently unable to solve difficult albeit standard collective action problems. It is rare that workers come together, and unexceptional when they fall apart (Hardin Reference Hardin1982, Reference Hardin2001). As long as defection from collective action retains its appeal, social division may arise. A far-sighted capitalist might hope to cultivate racism within the working class, but he might also try to impose prisoner’s dilemmas on them; indeed, one compelling definition of power is the ability to impose prisoner’s dilemmas on rivals (Elster Reference Elster1985), and “right to work” laws do just that. To sum up, both growth and social division can solve crises in the social reproduction of capitalist class relations, and social division can itself be decomposed into diverse forms, one of which is racial oppression.

Thus, when we consider those long stretches of capitalist history when growth fails to satisfy human needs, it may be that some generic form of social division is indeed required to solve the problem of capitalist stability. Racism is one historically contingent expression of that division. On these grounds we do obtain a functional explanation for racism: capitalist class relations do functionally explain race. But we are forced to also concede that racism is just one way to skin the cat. Racism may be explained by capitalism, even if it is not necessary for it. One’s death may be explained by cancer, even if it was not necessary for it.

Nevertheless, there are good reasons to think that race is particularly well-suited for maintaining the division compared to other forms of social division. First, as suggested above, race often divides not just at the level of individuals, but across entire social networks and institutions—particularly families, but also friendship groups, neighborhoods, churches, schools, and so on. Second, it is presumed by people to be biological, immutable, and heritable—in other words, it is robust to any process of cultural assimilation, and it defines groups on an intergenerational basis. Third, a person’s race is usually easily identified based on unchangeable phenotypic markers which cannot be concealed.Footnote 24 Gender, by contrast, may be presumed to be biological, immutable, and marked by unconcealable physical features, but families unite people across the gender divide; ethnicity, language, and religion may divide by social network, but are usually neither immediately observable nor immutable (e.g., one may convert from one religion to another or keep their beliefs private; a child of immigrants may learn to speak the dominant language unaccented). Non-racial forms of difference can and have been used to divide workers, but race seems almost tailor-made for the purpose.

Finally, phenomena can be functionally explained under one set of circumstances, then under changed circumstances merely survive as the fading residue of an old functional system. In the Trobriand Island example, rituals were functionally explained by their objective effects of reducing fear and getting people to fish in the sea. Apparently, after boats and improved fishing technology made the sea less dangerous, the rituals became less impassioned and more perfunctory. They did not disappear, but there was no longer a problem to be solved; the rituals weakened, even if they continued to be an in-built part of the institutions of religion.Footnote 25 Racism too was an important solution in a capitalist regime that offered little or no improvement in living standards for the vast majority; it is hard to imagine how the American slave-based and sharecropping economies could have stabilized without racism as a problem-solver.

But in a world where absolute forms of exploitation are less extreme and where other opportunities for dividing the working class are abundant, racism may no longer be functionally necessary for capitalism. This is the reason why we can observe capitalisms around the world that are not marked by deep internal racial segmentation. Nonetheless, even when a tight functional relationship loosens, its features may live on for some time. Apart from functionalist selection, simple historicist causal processes are also at work: for instance, the largely heritable nature of wealth and cultural capital means that present racial wealth and income inequalities are in some measure the effect of past racial wealth and income inequalities.Footnote 26 This is what people mean when they refer to the “legacies” of slavery and Jim Crow: that racism was a functional solution in early iterations of capitalist history means that racism gets built into the institutions of today and continues to have autonomous effects in the world. Still, absent the functional requirement, we should expect racialized inequalities to fade over time, and relative to the earlier periods, they certainly have. But to the extent that they persist, even at a lower level, analysts ought at least to weigh the possibility that racism continues to serve a functional role. Moreover, an historicist causal account may also imply a functional one: any specific practice whose effects stabilize the social system will tend to be reproduced over time as long as it works and is not outweighed by costs to elites. Racism, by this telling, persists because it emerged earlier than other functional analogs and because it kept (cheaply) dividing workers one generation after the next—call it the “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it” reproduction mechanism, in which there are simply no incentives among elites to change the practice (Stinchcombe Reference Stinchcombe1968). If racism had no beneficial effects for capitalists or meant serious costs for them, we might expect that struggles against racism were easier to wage and would find more committed fighters among the elite, or that state institutions would be much more aggressive in enforcing antidiscrimination laws, promoting integration, and reducing racial inequality.

Becoming Irish

One perspective suggests race is like Catholicism: the functional relationship has lost its explanatory purchase—Catholicism is no longer explained by its stabilizing effects on feudalism—but the institutions left in its wake trundle on. On the other hand, Catholicism is on the wane. With the fading of the functional relationship described above, it is conceivable that the ideology of race itself loosens its grip. If we grant that racism might be explained by capitalism but not necessary for it, we should be able to imagine race without its class component. Racial segmentation has historically fallen along class lines. It has, in other words, been characterized by some material exclusion—from access to land, education, housing, basic subsistence, good jobs, or other economic opportunities. And yet there is no reason to expect racial division to be forever fused to class division. The severing of this couplet is the topic of William Julius Wilson’s book, The Declining Significance of Race (Reference Wilson1980). And there is good reason to believe that without its class dimension, the belief-dependent folk concept of race should begin to dissolve into ethnicity.Footnote 27 In other words, without the class dimension, Blacks in the United States would be like the Irish or Italians; they would merely be a national-cultural ethnic group with a unique history, unique foods, songs, traditions, mythology, and so on.