In January 2009, Peking University acquired a large cache of bamboo-strip manuscripts dated to the Western Han, whose contents promise to significantly advance our understanding of early China.Footnote 1 The collection contains over 3,300 pieces of bamboo in total, of which 1,600 strips are still intact.Footnote 2 These strips are generally well preserved, and the writing on them is clear, making the Peking University Han manuscripts extremely convenient sources to study. Highlights from this cache include one of the most complete early editions of the Laozi 老子 discovered to date; the lost Daoist work Zhou xun 周馴—listed as Zhou xun 周訓 in the Han shu 漢書 Yiwen zhi 藝文志; an historical treatise on the passing of the First Emperor of Qin and its immediate aftermath titled Zhao Zheng shu 趙正書; a fu 賦 rhapsody called Fan yin 反淫 that echoes the received Qi fa 七發; and an amusing vernacular rhapsody (or su fu 俗賦) on the domestic strife between a scorned wife and lovely concubine, titled Wang Ji 妄稽; in addition to medical recipes, divination materials, and fragments of masters’ works.

Within this collection is also an extremely important edition of the Cang Jie pian 蒼頡篇, a text that is the subject of my own research.Footnote 3 The Cang Jie pian is an early character book or zishu 字書, purportedly authored in part by Li Si 李斯, the Qin statesmen well known for his advocacy of writing reform.Footnote 4 Although the Cang Jie pian was initially lost sometime during the Song dynasty, portions of the text have been rediscovered among the manuscript finds of the past century.Footnote 5 Unfortunately, most of these finds are fragmentary, while the two longer editions from Fuyang 阜陽 and Shuiquanzi 水泉子 are poorly preserved and not yet adequately published.Footnote 6 The Peking University Cang Jie pian is the most complete version to date, bearing over 1,300 characters and even including complete or nearly complete chapters, offering us an invaluable glimpse into the nature of this text during the Western Han.

After an initial flurry of press releases, in 2011 the Chinese journal Wenwu 文物 printed a series of articles introducing the contents of the Peking University Han manuscripts, as well as a report analyzing certain physical characteristics of the artifacts.Footnote 7 The next year, the Laozi manuscript was published in full, under the title Beijing Daxue cang Xihan zhushu (er) 北京大學藏西漢竹書貳.Footnote 8 Although this was the first book to be printed, it still—somewhat confusingly—retains the designation of Volume Two (貳), as the original publication schedule intended for it to follow the Cang Jie pian volume. Four additional books from the Beijing Daxue cang Xihan zhushu series have recently seen print, including Volume One (壹) with the Cang Jie pian, Volume Three (叁) with Zhou xun, Zhao Zheng shu, Ru jia shuo cong 儒家說叢, and Yinyang jia shuo 陰陽家說, Volume Four (肆) with Wang Ji and Fan yin, and Volume Five (伍) containing the divination texts Jie 節, Yu shu 雨書, Zhen yu 揕輿, Jing jue 荊決, and Liu bo 六博.Footnote 9 Each of these books includes photographs of the bamboo strips (rectos) in their original size and magnified, along with infrared photographs for areas that are unclear, hand drawings of the strips’ versos, tables of measurements for physical aspects of the artifacts, charts comparing textual parallels with other works when appropriate, and often thematic research essays. Two more books are forthcoming, namely Volume Six (陸) covering the daybook materials Ri shu 日書, Ri ji 日忌, and Ri yue 日約, and Volume Seven (柒) with the medical recipes.

Meanwhile, in order to keep scholars apprised of their ongoing work, the Peking University Excavated Manuscript Research Center has been releasing online newsletters, which are available in PDF format through the Peking University Ancient History Research Center's website.Footnote 10 These briefs provide insights into the reception and early treatment of both the Han and Qin caches, minutes for conferences held on these collections, notices on the publication of the edited volumes, bibliographies for research conducted by members of the center, and other pertinent information. Nine briefs have been written to date. They are an invaluable resource for any scholar looking to familiarize themselves with the Peking University strips.

Despite the immense importance of these new manuscripts, research on the Peking University Han bamboo strips is hampered by the fact that the collection was not archaeologically unearthed, but rather purchased from an antiquities dealer.Footnote 11 While the last century has witnessed the discovery of unprecedented numbers of early Chinese manuscripts written on wood, bamboo, and silk, unfortunately not all of these artifacts were collected through controlled scientific excavation. The Peking University strips are the latest example of a recent trend in which major academic institutions within China have acquired caches of manuscripts from the antiquities market.Footnote 12 In lacking any detailed provenance or scientifically documented archaeological context, the Peking University manuscripts are robbed of crucial data that could have significantly furthered scholarship.Footnote 13 The uncertainty of their origins moreover opens the door to speculation that these texts are in fact only modern forgeries, and thus of little academic value.Footnote 14 There are also scholars who oppose the study of artifacts purchased on the antiquities market—authentic or otherwise—on the grounds that this is academically irresponsible (by knowingly “validating” dubious materials), and moreover fosters a trade for pilfered artifacts, thereby indirectly supporting the destruction of archaeological remains.

It is therefore necessary to establish the authenticity of the Peking University Han strips, and address concerns over the impact scholarship on purchased caches of bamboo strips may have on preserving China's cultural heritage. In this article, I will offer an argument, from the perspective of my own research on the Peking University Cang Jie pian, both for why I am convinced that this manuscript is genuine, and why we should not feel constrained in researching the Peking University corpus. After a review of current debates over the authentication of purchased collections of bamboo strips, I discuss the methods employed to authenticate the Peking University Han manuscripts in particular. As part of this discussion, I will refute statements made by Xing Wen 邢文 in a recent article claiming that the Peking University Laozi is a forgery.Footnote 15 Next I will present a method for positively authenticating purchased manuscripts of unknown provenance, taking the Cang Jie pian as an example and demonstrating its antiquity. I conclude by addressing the professional ethics of working with these collections, responding to concerns most publicly raised by Paul Goldin and giving voice to the “rescue archaeology” orientation largely adopted in Chinese scholarship.Footnote 16

1. Recent Debates on the Authenticity of Purchased Collections of Bamboo Strips

Purchased collections of bamboo-strip manuscripts offer exciting new evidence for the study of early China. They also however present a great risk to our field, as we begin to develop new narratives informed by these texts which may ultimately be misguided if the manuscripts are proven to be forgeries. It is thus surprising—and unfortunate—that currently there is no transparent process by which we may authenticate purchased collections of bamboo strips. A handful of experts are often called upon to render initial judgment behind closed doors, following which other researchers are usually left to rely on their connoisseurship. Scientific methods of authentication, such as radiocarbon dating, are at times employed, but without any regularity.Footnote 17 Indeed, the question of forgery has been a topic conspicuously avoided in formal Chinese publications dedicated to these paleographic sources, perhaps to escape criticism of respected peers who would then be held responsible for potentially very costly mistakes in judgment.Footnote 18 Silence is therefore the loudest condemnation in China at the moment, as an absence of research on such collections most strongly signals scholarly unease on their authenticity.Footnote 19

One of the few Chinese scholars to broach the topic of authenticating these newly purchased bamboo-strip manuscript collections early on is Hu Pingsheng 胡平生, who has currently authored three articles on this subject.Footnote 20 Hu warns that forged strips have already flooded the antiquities market, not only in Hong Kong but also in other regions of China as well. While no systematic survey exists to aid scholars in tracking when and where potential forgeries came on the market, or who might have bought them, Hu does list a number of instances that he can recall or with which he was personally involved (having been asked to provide authentication).Footnote 21 For example, in 1995 a large cache of strips was sold in Japan, which radiocarbon dating later proved to be made of wood from the 1970s. The same year fake strips were also offered to the National Palace Museum 台灣故宮博物館 and Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica 中央研究院歷史語言研究所 in Taiwan. A university in Hong Kong at that time did buy some strips, in which a few genuine specimens were mixed within many fake ones, revealing just how complicated authenticating an entire cache may be.Footnote 22 Hu also reminds us of the Sun Wu bingfa 孫武兵法 manuscript discovered in Xi'an in 1996, a forgery that at first received much media attention. More recently, Hu discusses multiple occasions when individual collectors had either contacted him directly, or posted in online forums, to evaluate their private holdings, which inevitably turned out to be fakes. A silk manuscript was even purchased from Beijing's “Ghost Market”—Panjiayuan 潘家園—in 2007, as forgers continue to diversify their media.Footnote 23 These are just a few of the examples raised by Hu that speak to the immense problem at hand.

Of course, the forgery of bamboo-strip manuscripts is not purely a modern phenomenon. In the Han shu chapter Rulin zhuan 儒林傳, Ban Gu 班固 recalls how a 102 chapter edition of the Shang shu 尚書 was dismissed as counterfeit, its content deemed too unsophisticated to be the actual classic.Footnote 24 It is instructive that this alleged imitation was presented to the throne during Emperor Cheng's reign (32–7 b.c.e.), in response to a call by the court for ancient-script manuscripts to be brought in from among the masses. This was a time marked by classical polemics, when the words of the ancient sages were both sacred and contested. In this intellectual climate, forging a work like the Shang shu was one means of garnering political influence. Indeed, as Yoav Ariel shows in his study of the Kong congzi 孔叢子, the authenticity of the classics was a topic of great concern by the end of the Han. For the compilers of the Kong congzi, however, the criteria for “authenticity” vis-à-vis textual identity were more liberally defined.Footnote 25 Thus, in an anecdote from the chapter Zhijie 執節 of this work, when the Warring States figure Yu Qing 虞卿 is censured for authoring a text with the title of Chun qiu 春秋, borrowing Confucius’ name for his classic, Yu retorts: “A classic draws from the constancy of affairs. If a work speaks to these constant principles, then it is a classic. If it is not by Confucius, does this then mean it is not a classic?”Footnote 26

Today textual forgery has once again become a topic of great concern. More than a century ago, Aurel Stein had already uncovered a rather sophisticated forgery racket headed by Islam Akhun, which had previously deceived the eminent scholar A. F. Rudolf Hoernle and other Western explorers.Footnote 27 In the case of bamboo-strip manuscript forgeries, however, it appears that the industry was spurred on by the remarkable finds of the 1970s, such as those from Yinqueshan 銀雀山, Mawangdui 馬王堆, Shuihudi 睡虎地, and the latest Juyan 居延 cache. As Hu argues, most of the fake manuscripts he has inspected are modeled after discoveries from the 1970s onward.Footnote 28 He writes that “starting from the beginning of the last century, but especially since the 1970s, the excavation of wood and bamboo-strip manuscripts and silk documents has been a bright spot for the field of [Chinese] archaeology, while the forgery of these manuscripts has also gradually increased, and thus naturally the authentication of bamboo and silk manuscripts has become a new field of research [in its own right].”Footnote 29

When he penned “Gudai jiandu de zuowei yu shibie” in 1999, Hu seemed confident that the quality of the forgeries currently on the market was low enough that they may be easily detected by experts in the field. Hu recalls for instance how, during a visit to the Gansu Provincial Institute of Archaeology in 1996, he first saw a news report claiming that a Sun Wu bingfa bamboo-strip manuscript was discovered in Xi'an. Hu and his colleagues, “long-time experts in wooden and bamboo-strip manuscripts, all exclaimed that the strips must be fakes as soon as they saw the report.”Footnote 30 In this instance, the bizarre binding method and use of black paint for writing immediately signaled problems regarding the authenticity of this manuscript to the eyes of scholars like Hu who have personally handled numerous collections of genuine strips.Footnote 31 Considering the complexity of such texts, Hu argues that only highly skilled paleographers would be able to convincingly forge a bamboo-strip manuscript, and any dedicated scholar with this skill set would have no motivation to do so.Footnote 32

With his updated article in 2010, “Lun jianbo bianwei yu liushi jiandu qiangjiu,” Hu still firmly holds that fakes today have yet to reach a level of sophistication where they could confuse a connoisseur.Footnote 33 He does admit, nonetheless, that forgers have grown craftier in their trade and seem to have made advancements since 2008, both in aging techniques (that is, falsely weathering the bamboo or wood) and in imitating archaic calligraphy.Footnote 34 Indeed, Hu writes that he was motivated to expand upon his previous article when, on being called to authenticate a batch of bamboo strips he quickly deemed fake, he learnt that, just the previous day, another expert had issued a report rendering the same collection authentic. It seems that confusion abounds. As Hu wondered over how museums today are still purchasing these forgeries—even putting them on brazen display—he “felt with great sorrow that ‘the authentication of bamboo and silk manuscripts’ has truly become an issue to which we must pay more and more urgent attention.”Footnote 35

Elaborating upon how to detect a fake manuscript, Hu outlines four basic areas where the forgeries often come up short: textual errors; physical constitution of the manuscript; calligraphy; and provenance.Footnote 36 For example, regarding the physical constitution of strips, forgers will often utilize wood or bamboo that is too fresh in appearance, or if they have tried aging the strips, the coloring will be too even, as genuine pieces will often have varying shades of color, despite coming from the same location. It is likewise difficult to mimic the precise calligraphy of a given period, and forgers copying from a model may miswrite graphs, producing forms that do not exist (this is particularly true with the less familiar Chu script). Content errors also abound, from misunderstanding dating conventions, to the inclusion of anachronistic anecdotes, and more nuanced gaps in vocabulary usage. Finally, Hu cautions that most forged strips are coming from either Hubei or Lanzhou.Footnote 37 These are regions where authentic manuscripts have been discovered and are on display in museums, museums that often also happen to sell facsimile models that a forger may easily use for copying.Footnote 38

While initial concerns over the first high-profile purchase of bamboo-strip manuscripts by the Shanghai Museum in 1994 may have been expressed in private, criticism was not published in formal scholarly venues. It seems that the concerns of most scholars were alleviated by the assumption Hu advocates: that these manuscripts were far too complex for anyone other than an expert paleographer to counterfeit, and such an expert would have little motivation to do so in the first place. After the Tsinghua University acquisition in 2008, however, various scholars have begun to raise doubts more publicly. Jiang Guanghui 姜廣輝 for example has released a series of articles questioning whether the Tsinghua strips are authentic.Footnote 39 He warns that although it would be difficult to fake manuscripts like these, we should remain vigilant: it is always possible that there are technically skilled, educated, and well-funded forgers out there who have the means to deceive us.Footnote 40 Jiang calls for a return to more traditional forms of textual criticism to catch subtle content-based mistakes an otherwise sophisticated forger may still make.Footnote 41 He thus attempts to find instances where, for example, vocabulary is misused, the grammar is incorrect, there are logical inconsistencies in the text, and anachronistic ideas are advanced or taken from later commentaries. Although I do not find the specific evidence Jiang raises against the Tsinghua strips to be convincing, his approach is largely representative of the type of critiques which have begun to gradually appear in published literature.Footnote 42

More recently, a very public debate was initiated by Xing Wen when he declared the Zhejiang University Zuo zhuan manuscript to be fake in a series of Guangming ribao 光明日報 articles,Footnote 43 to which Cao Jinyan 曹錦炎, the main editor of this collection, likewise published his own refutations.Footnote 44 Xing Wen's suspicions are grouped around three areas, which accord with Hu's earlier categorization: the unusual physical constitution of the strips, errors in textual content, and mistakes in the calligraphy. I will not list all his criticisms here, but allow me to offer one example.Footnote 45 Xing notices that the writing on the Zhejiang University edition of the Zuozhuan 左傳 is across a series of broken strips, with the text accommodating the breaks to run continuously, when we would expect gaps in content instead.Footnote 46 That is to say, sections of text will often end coincidently right where the breaks occur, and even the writing of individual characters or the spacing between them is unaffected by splits in the bamboo. Xing claims that this curious feature, along with the fact that the strips are uneven in length and width, and lack any notches or binding marks, varies significantly from other excavated examples of bamboo-strip manuscripts.

Cao Jinyan, for his part, appeals to the radiocarbon dating and ink tests which were conducted on the Zhejiang strips as undeniable proof of their authenticity, and asserts that there are in fact examples of excavated bamboo strips of uneven dimensions, and without notches or binding marks.Footnote 47 However, on this former point, Xing had already questioned the representativeness of the samples.Footnote 48 Was a forger able to trick these scientific tests, perhaps by obtaining blank ancient strips and writing new text on them? Or are we seeing a different form of manuscript production here, where an ancient scribe employed already broken strips as a textual carrier (perhaps as practice writing, which might also explain many of the calligraphy and content errors Xing Wen also proposes)?

The debate between Xing Wen and Cao Jinyan is instructive because it aptly reflects the sorts of anxieties keenly felt in the study of early China today as we address how best to handle these new sources with unknown provenances. No longer are scholars satisfied with the excuse that these purchased collections of manuscripts are too sophisticated to be a forgery. Scientific tests like radiocarbon dating are increasingly being adopted, but they are not infallible; we must consider, for instance, the representativeness of the samples, margins of error, and the possibility of contamination. Connoisseurship then must continue to play a role in authenticating bamboo-strip manuscripts, yet here too scholars are now demanding more transparency. Hopefully, inspiration will be drawn from other fields of study that have faced similar issues with authentication as well.Footnote 49 For the moment however, early China scholars are unfortunately left to their own devices when attempting to determine the authenticity of bamboo-strip manuscripts.

2. Authentication of the Peking University Han Bamboo Strips

The Cang Jie pian manuscript central to my research was included among the cache of Western Han bamboo strips donated to Peking University early in 2009. The strips are said to have arrived at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Arts and Archaeology at Peking University on January 11 of that year, though the donation was inevitably the result of a longer process of investigation and negotiation.Footnote 50 Few details have been published about the circumstances surrounding the actual purchase of this cache. Tsinghua University's acquisition of a similar collection from the Hong Kong antiquities market however might provide a comparable scenario, for which we fortunately have more documentation.Footnote 51

Tsinghua University formally received their collection of bamboo strips on campus on July 15, 2008. Just over a month prior, in June 2008, Tsinghua University officials had already begun to discuss acquiring the collection. Li Xueqin 李學勤 and other scholars were likewise asked to ascertain the academic value of the artifacts beforehand. Moreover, there is reason to believe that the Warring States manuscripts eventually donated to Tsinghua University were already for sale as early as the winter of 2006, at least two and half years before their final purchase, having been seen by Zhang Guangyu 張光裕 on the market at that time.Footnote 52

If we may assume that a similar time frame was required for Peking University to adjudicate the strips and arrange for their procurement, then it is likely that there was knowledge of this cache by the end of 2008 at the latest, while the actual artifacts were unearthed from their original archaeological site and above ground for an indefinite amount of time beforehand. Hu Pingsheng also offers indirect confirmation of this timeline. He states that “at the end of 2008, Li Jiahao 李家浩 and I participated in the authentication of a cache of looted Han strips, led by Professor Zhu Fenghan 朱鳳瀚 of Peking University's History Department. After we confirmed that the strips were genuine, Peking University acquired them for their preservation.”Footnote 53

Following the initial cleaning, preservation, and photography of the Peking University bamboo strips, a conference was convened on November 5, 2009, where many of the foremost experts on this class of artifact were invited to discuss the nature of the manuscripts. Minutes from this conference, along with abbreviated comments by the experts who attended, are available in the second brief issued by Peking University's Excavated Manuscripts Research Center, part of the series reporting on their continuing study of the manuscripts.Footnote 54 Judging from the comments provided, the consensus of these experts was that the Peking University bamboo strips are in fact Han period artifacts.

There are, however, a few scholars who mention they originally questioned the authenticity of the Peking University cache. Hu Pingsheng, for instance, confesses that he at first doubted the strips were genuine, because when he initially viewed pictures of them he did not see any traces of binding marks or notches. His concerns were alleviated though when he was shown clearer photographs, which revealed the existence of not only binding marks and string remnants, but also how the strips were splintering, in a way that is typical for artifacts of this type and commonly encountered by those who clean and prepare such strips.Footnote 55 Song Shaohua 宋少華 also agrees with this point, emphasizing how these particular features cannot be faked. Although Song first believed the Peking University strips were a forgery, he was now convinced of the authenticity of the collection.

According to the minutes from the November conference, it appears that the invited experts were not only provided with photographs of the strips, but they also had an opportunity to view the artifacts in person.Footnote 56 Peng Hao 彭浩 however requests that the Peking University editors eventually publish a report on the methods they used to authenticate the strips, reminding them how questions still linger about the Shanghai Museum collection because they neglected to publish sufficient data on their AMS radiocarbon testing.Footnote 57 He goes on to wonder about how the red pigment coloring the Peking University daybook (Rishu 日書) was made to stick to the strips so remarkably well, especially considering the primitive technology available in those times—perhaps raising a subtle critique at the strips’ authenticity.Footnote 58 In any case, Peng Hao's request, also echoed by Zhao Guifang 趙桂芳, suggests that scientific data of this sort was not made available to the experts at the conference.

Two years later, a report was issued by Peking University's School of Archaeology and Museology 北京大學考古文博學院 offering the results of their scientific analysis of the Han strips.Footnote 59 They observed the cellular structure of three samples of bamboo, and identified them as Phyllostachys or gangzhu 剛竹, which accords with expectations. Two of the samples however were taken from strips without writing, with the third cut from the end of an unlabeled suanchou 算筹 divining rod, which might lead one to question how representative these pieces truly are. Fragments of the binding string were also analyzed, and shown to be structurally consistent with ma 麻 hemp, and the authors offer a preliminary identification of Boehmeria or zhuma 苧麻. This is a form of hemp that again was available in the Han period. Crusted onto the surface of the hemp were yellow contaminants, while grains of soil and bacteria were lodged within the fibers. Finally, the red pigment that Peng Hao wonders about was also subjected to laser-induced Raman spectroscopy, and found to be zhusha 朱砂 cinnabar.

Notably absent from the scientific analysis conducted by Peking University's School of Archaeology and Museology however is any discussion of radiocarbon dating for these strips. In the fifth brief issued by Peking University's Excavated Manuscripts Research Center, announcing the overviews published in Wenwu 2011.6, they call these scientific results “partial 部分,” perhaps hinting at additional tests.Footnote 60 Moreover, in the same brief, an update is given for the Peking University team's work on editing the other recently acquired cache of Qin strips, where it is reported that radiocarbon dating was planned for the Qin strips.Footnote 61 And indeed, the following year the results for these tests were given in Wenwu 2012.6.Footnote 62 Nothing however has been mentioned in these or later briefs about radiocarbon dating for the Han strips. The lack of scientific dating for this cache of Han bamboo strips is a serious concern when evaluating their authenticity.

In the general overview to the Peking University Han manuscripts in the same issue of Wenwu, the editors date the majority of manuscripts to the mid-Western Han, most likely to the end of Emperor Wu's 武帝 reign (140–87 b.c.e.), and no later than that of Emperor Xuan 宣帝 (73–49 b.c.e.).Footnote 63 This conclusion seems to have been reached primarily based on a comparison of the manuscripts’ calligraphic style and character forms against other excavated caches.Footnote 64 The clerical script of most Peking University manuscripts is distinctly later than that found on the Zhangjiashan 張家山, Mawangdui, and Yinqueshan manuscripts, which is close to Qin clerical or early Han clerical script, while being not quite as mature as the writing found on the Dingzhou Bajiaolang 定州八角廊 strips.

With the Peking University Cang Jie pian, however, we cannot so easily rely on an analysis of calligraphic style and character forms to date the text. Zhu Fenghan describes the calligraphy in the Cang Jie pian as at times closer to Qin clerical script (as seen with the Shuihudi cache), while many characters even preserve seal script forms, contrasting sharply with the other strips from this collection.Footnote 65 Zhu attributes these features to the close relationship between the Cang Jie pian and the earlier Shi Zhou pian 史籀篇, as stated by the Han shu Yiwen zhi (and corroborated by the Shuowen Jiezi 說文解字 postface).Footnote 66 In short, the Cang Jie pian might incorporate deliberately archaic calligraphic styles and character forms as a result of its function as a character book. This purposeful archaizing of writing would complicate any attempt to date the text based on calligraphy alone.

To summarize the conversation above, we are confronted with the following facts pertinent to authenticating the Peking University manuscripts: (1) There is no detailed provenance for this cache. Besides the date that the strips were donated to the university, additional information is not available about its purchase or time on the market beforehand, though we may surmise that by the end of 2008 certain scholars were aware of the cache. (2) Although a few scholars were at first suspicious, the consensus from experts invited to examine the cache is that the strips are authentic. How the bamboo strips splintered, the remnants of binding, and similar physical features are mentioned by connoisseurs as telling characteristics for genuine strips. (3) The type of bamboo used is consistent with other excavated Han strips, and we know the hemp and cinnabar on the strips was also available in early China. (4) The calligraphy on the majority of the Peking University manuscripts is comparable to other Han examples. With the Cang Jie pian, however, this type of comparison is perhaps frustrated by its at times purposefully archaic nature. (5) Results from scientific dating methods, such as radiocarbon dating, are not available for this collection of strips. Considering these points, it would appear that we are left to rely mainly on the connoisseurship of the editors and other experts who have personally handled the Peking University Han manuscripts.

2.1 A Response to Xing Wen's Critique of the Peking University Laozi

In a recent Guangming ribao article, Xing Wen warns that this places other scholars in a very precarious position. Xing believes that the Peking University Laozi 老子 manuscript is in fact a forgery, and suggests that the editors of the collection have been intentionally misleading in their presentation of the data, so as to quiet criticism about the text's genuineness.Footnote 67 His critique is based primarily on observations that the writing seems to accommodate or morph around breaks in the strips, and that there are irregularities in the manuscript's verso marks and material presentation.

Even if we agree with Xing's assessment of the Laozi manuscript, we must keep in mind that this does not necessarily prove that the entirety of the Peking University collection—including the Cang Jie pian—is fake. The authenticity of each discrete manuscript, and indeed every single strip in the collection, ought to be considered individually, to whatever extent possible. This is particularly true as there is no guarantee that all the strips in this cache have the same provenience, although it does seem likely. In the interest of addressing concerns about this collection writ large however, I will respond to the points made in Xing's assessment.

In declaring the Peking University Laozi to be fake, Xing Wen raises the following main arguments. Points one and two relate to his “technical calligraphy analysis,” while points three through six all pertain to the verso marks, either directly or indirectly:

-

1. Xing believes that the character “無” on strip #2 of the Peking University Laozi is written in a curious fashion.Footnote 68 The character is written to slant in an unusual way that appears to avoid the break at this point in the bamboo strip, with the right side of the character seemingly following alongside the crack, particularly in its bottom-right quarter. The character thus appears to squeeze itself into the space remaining on the broken bamboo piece. This, Xing suggests, is evidence that “無” was written after the bamboo strip was split in two, a practice that he asserts was not present in early China.

-

2. Xing also questions the integrity of the character “得” on strip #52 which straddles the break in the bamboo. The top-right half of the character remains on the upper piece and the bottom-left half of the character is found on the lower piece.Footnote 69 Xing argues that the break hides the fact that “得” was miswritten. A proper reconstruction, according to Xing's own analysis, reveals that the construction of “得” here is not typical, and in fact does not even constitute a complete character.Footnote 70 On this point, he accuses the editors of the cache of purposefully manipulating the data they published to mislead readers, so that they might not notice the misshapen “得” graph. A forger must have written part of the character on one piece of broken bamboo, and then tried to finish the character on another, with poor results.

-

3 Considering the overall conformity of the verso marks, Xing then argues that the lines that appear to cross over multiple strips are not in perfect alignment. Rather, in certain instances, the line on an individual strip is carved at a slant whose angle differs from the lines found on neighboring strips. Two examples Xing highlights are the verso marks on strip #86 in comparison with those running from strip #87 onwards, and those on strips #182 and #183, for which he also supplies hypothetical extensions. Noticing that their gradients are not the same, Xing believes that a forger attempted to replicate a straight line, but failed to accurately connect it across multiple strips.

-

4. Xing also observes that if we were to try to align the verso marks as closely as possible, we would need to adjust the height of the strips, rearranging how they are currently presented in Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu (Volume 2). In doing so, the layout of the manuscript would be altered, with the tops and bottoms of the strips not falling level with one another, but rather positioned at various heights. Such a layout is not what we would expect to find for an ancient bamboo-strip scroll. Either the layout of the manuscript (in terms of the varying strip height) betrays it as a fake, or once again the verso marks do not accurately align with one another, betraying them to be fake.

-

5. Strips #84 and #187 are also devoid of any line-like mark on their versos. The absence of marks on these two strips is noteworthy because they seem to be inserted among other strips where there is a clear running line. Xing emphasizes that, to explain this oddity, the editors for the Peking University Laozi suggest that the manuscript was “written first and then bound.” They argue that a mistake must have been made in the initial writing on the original strips (with the appropriate verso marks), and that these strips with mistakes were later replaced with other strips (that did not have verso marks), which were then bound together into the manuscript we now have.Footnote 71 Xing however points out that the writing on the Laozi manuscript seems to avoid where the binding strings were laid, which to him suggests that it was instead “bound first and then written upon.” If this were the case, then Xing finds no explanation for the insertion of these strips with blank verso marks, and thus assumes that the manuscript was faked.

-

6. In critique (2) above, Xing disputed how the character “得” was written in strip #52. He further notes that in the hand drawing of its verso, only the top piece includes a line-like mark, while the bottom piece (or the right side of the drawing) does not show any such mark. He takes this as evidence that the two pieces are actually not from the same original bamboo strip. According to Xing, this would demonstrate that the text was written and supposedly pieced together on these separate broken fragments, thus confirming a forgery.

Despite the clarity of the published photographs, when investigating materially complicated features of the bamboo, such as writing around breaks in the strips or the faint verso marks, ideally one should refer to the actual artifact. This is particularly true since all photographs of these bamboo-strip manuscripts are doctored to some degree in preparation for publication, even if this means simply removing the background color.Footnote 72 Caution is doubly warranted when relying solely on the hand drawings, as this entails yet another degree of separation away from the artifact itself. In this case, production of the hand drawings for the verso marks was based on measurements conducted in the fall of 2010, shortly after the importance of this feature was first realized in full.Footnote 73

A personal inspection of the Laozi manuscript artifact on two occasions revealed to me that most of Xing Wen's critiques were based on unclear or incomplete data.Footnote 74

During my first inspection in September, I noticed that there is in fact a line-like verso mark on the bottom piece of strip #52 that was not recorded in the editors’ initial measurements or hand drawings, contra Xing's critique (6). See Figure 1. The gradient of the line seems to match that of the mark found on the top piece of strip #52, the left side, that is, of the verso in the hand drawing. Moreover, it anchors the two pieces in such a way that Xing Wen's new reconstruction is impossible, undermining the version of “得” for which he gives his “technical calligraphy” analysis, in critique (2).Footnote 75 How the editors arranged the recto photographs is more in line with how the strip would have been originally presented vertically, except of course that the pieces should overlap slightly horizontally as well, and not be angled off to the side of one another for convenience of display.

Figure 1. (color online) Verso mark on strip #52 (photographs taken on October 26, 2016, at Peking University).

In October when we were observing the strips again and taking photographs of the versos, Han Wei discovered that the bottom piece of strip #32 also bears a verso mark that was missed in the initial measurements and hand drawings. The verso mark is found below the break in the strip. Xing Wen refers to strip #32 when arguing in his critique (4) that the heights of the strips were not level in the bound Laozi manuscript. He assumed that the break represents where the verso mark should have been on strip #32 (as the bamboo will often split along these verso marks, where it is made structurally weaker), and subsequently aligns this group of strips with #32 placed significantly lower than its neighbors. I will discuss below why this methodology for arranging the layout of the manuscript is problematic, however in this case the newly discovered verso mark accords well with those marks found on the neighboring strips, meaning that this set of strips would be arranged in the bound manuscript with level heights.

Figure 2. (color online) Verso mark on strip #32 (photographs taken on October 26, 2016, at Peking University).

The mark on the bottom piece of strip #52 is close to the break in the bamboo, and is extremely faint and hard to notice. It would have been easy to overlook during the initial measurements of this feature. The mark on the bottom piece of strip #32 is positioned further away from the break, and is clearer to the eye, with an almost reddish-orange hue present from what seems to be tearing in the bamboo. It was however hidden under the metal identification tag, which is attached to the string that binds together the glass plates securing the strip. Han removed the glass plates for this strip when we were viewing the Laozi in October, and only then noticed the verso mark.Footnote 76 In both cases, the mistaken omission of these verso marks was unfortunately replicated in the publication of the Laozi verso hand drawings.Footnote 77 I may now confirm that critiques (2), (4), and (6) are based on incomplete data, which could have been rectified upon inspecting the artifact itself. Note however that I was not able to detect verso marks on strips #84 or #187, which Xing raises in critique (5). Cognizant of the difficulty of identifying this feature, I would recommend they be checked again more thoroughly.

Another observation has to do with the angle of the line-like verso marks, which Xing Wen believes to be irregular in critique (3). The measurements taken for the verso marks are inevitably imprecise, as they were rounded to the nearest tenth of a centimeter.Footnote 78 This is a crucial point, as any dramatic discrepancies to the gradient of verso lines across neighboring strips—as shown in the hand drawing—might amount to a mathematical illusion, rather than being a sign of forgery. Consider for instance the marks on strip #182 and #183, which Xing raises in his article as an example for verso lines with widely divergent gradients. According to the “Xi Han zhushu Laozi zhujian yilanbiao 西漢竹書老子竹簡一覽表,” the width of each strip is the same, at 0.8 cm, while the overall height for the verso marks (that is, measured from their topmost entry on the left of the strip to their bottommost exit on the right) is 0.4 cm and 0.6 cm respectively, leading to a 10.3° variance in the line gradient. Sensitive to the fact that the data is rounded off, however, it is possible that the actual width of each strip is, when not rounded off, 0.80 cm and 0.84 cm, while the overall height for these verso marks could be 0.44 cm and 0.56 cm in turn. This now gives a more tolerable 4.9° difference, which is a nearly negligible 2.45° off from a theoretical mean gradient for the ideal verso line.Footnote 79

In my examination of the verso marks for strips #182–85, I noticed that for the most part the angle of the line running across these four strips was largely in accord, with the gradient to the line on strip #184 in particular more amenable to the series than reflected in the hand drawing. The only exception though was still the verso mark on strip #183, which does seem to have a slightly steeper gradient than the others. See Figure 3, which shows the versos of strips #182–85, from left to right respectively, compared to the hand drawing. When observing the artifact's verso, however, it is apparent that the strip is warped, curving with a slight bend to the right. The bend in the strip is not obvious from the hand drawing, but may be seen in the original-sized photographs, where it appears curving towards the top left from the recto. This warping makes the verso line seem steeper in comparison to those on the other three strips here, when in actuality there is not a dramatic difference, should the strip be straightened.Footnote 80

Figure 3. (color online) Verso marks on strips #182–85 (photograph taken on October 26, 2016, at Peking University; the hand drawing and recto photograph are after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 116 and 26, respectively).

Of course, it is not always possible for every scholar who writes about these manuscripts to examine them in person, as access is often restricted for preservation purposes or, for those of us based outside of China, not logistically convenient. To help scholars verify the observations reported above, I have included photographs taken during my second viewing of the Laozi manuscript, on October 26; hopefully further documentation will be made available in the near future by the Peking University editors as well.Footnote 81 Appreciating however that most scholars will not be able to personally confirm my findings by handling the artifact itself, I will offer below additional responses to Xing Wen's critiques, using data publicly available, such as the photographs and “Yilanbiao” published in Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu (Volume 2). My emphasis here nevertheless is that in working with manuscript artifacts (as with any other object of study for that matter), we need to appreciate how the data we rely on is collected and presented, as well as the limitations that are then placed upon their use in our research. One of my major reservations regarding Xing's methodology is that it lacks such an appreciation for the limitations of either the artifact itself or the published data provided.

Let me therefore now address, in turn, each of Xing's critiques listed above exclusively on the basis of publicly available data. To this end, it should also be noted that about a month after Xing Wen published his critique of the Peking University Laozi, Li Kai 李開 offered an initial defense of the manuscript, printed again in Guangming ribao. In the same issue, Xing Wen answers Li Kai and provides further comments clarifying his position.Footnote 82 When relevant, details from this exchange are included in the discussion below; there are however aspects of Li's approach that I find problematic, which is why it is not treated in full here.Footnote 83 As this article was under review, a further brief response by Yao Xiaoou 姚小鷗 was published in Chinese, while Thies Staack also prepared his own defense of the Peking University Laozi in English.Footnote 84 Xing Wen has since replied to Yao's response, and I have also incorporated this in my discussion below when appropriate.Footnote 85

For the reader's convenience, I will post in italics Xing's argument in abbreviated form before my responses.

-

1. The character “無” on strip #2 seems to be written in a manner that intentionally avoids a break, suggesting it was written after the strip was split in two.

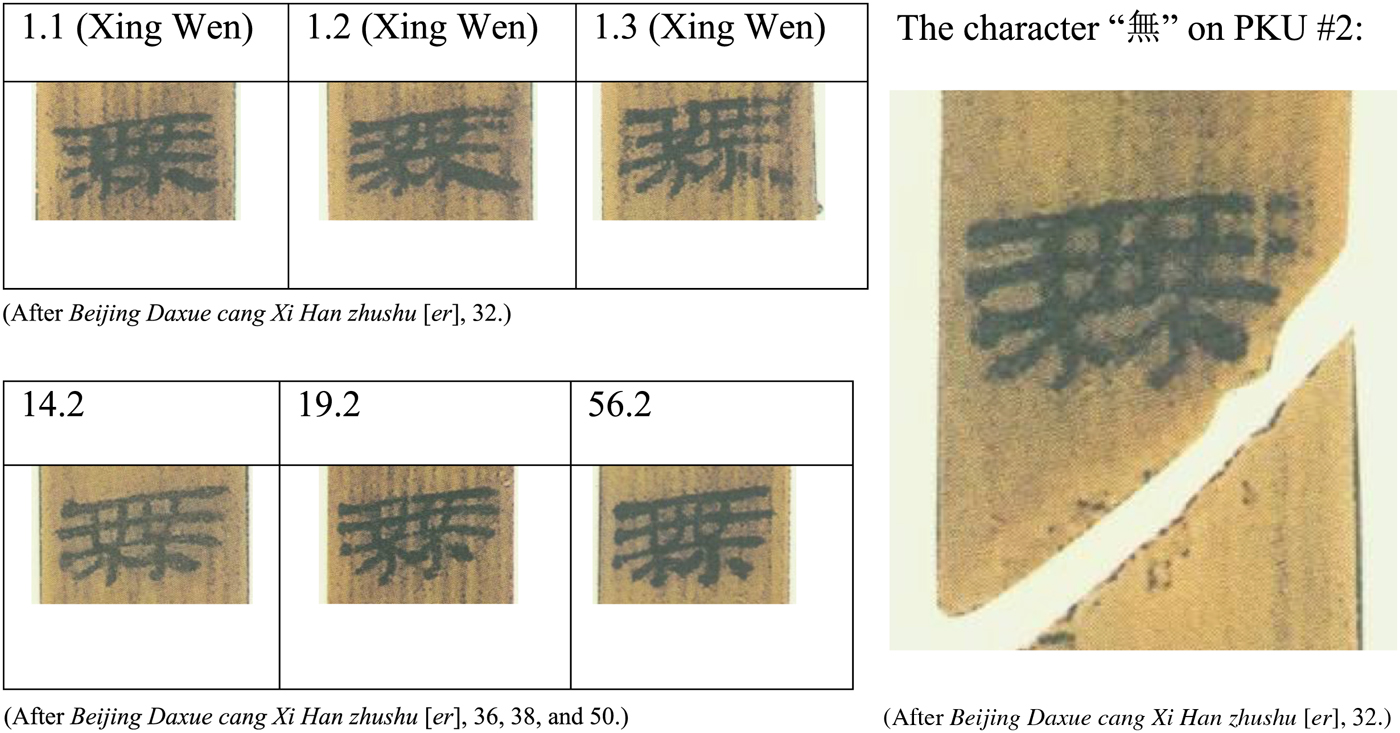

In his first article, Xing Wen offers images from only three other instances of the character “無” found on strip #1 of the Peking University Laozi. These three examples happen to exacerbate the difference Xing is hoping to highlight in how the characters were written. Even if we grant that the “無” found above the break in strip #2 is complete, a broader survey of how “無” is written across the entire manuscript will reveal that this specimen is not exceptional. It is possible that the perceived avoidance of the break in the bamboo is not actually a purposeful distortion of the writing by a forger's hand, but rather a mere coincidence in the positioning of the character vis-à-vis the remaining edge. Consider the following chart (Figure 4), which shows the examples Xing provides, followed by three other examples I have selected from elsewhere in the Laozi manuscript. For comparison purposes, I have also included an image of the “無” on strip #2 that Xing Wen believes was written to accommodate the break.

Figure 4. (color online) Instances of the character “無” in the Peking University Laozi.

If the reader were to look only at the examples Xing provided, it would appear that his argument holds: whereas the three “normal” “無” from strip #1 are aligned parallel to the right edge of the bamboo, or even slant outwards toward the edge of the bamboo in their bottom-right quarter, the “irregular” “無” from strip #2 has a dramatic slant inwards away from the bamboo's edge in its bottom-right quarter. Imagine instead however that Xing showed only the three examples I now provide: 14.2, 19.2, and 56.2.Footnote 86 They would paint an entirely different picture, as these also are written to have their right side slant inwards, away from the edge of the bamboo, seemingly pinching the character form into a more triangular shape. Amongst these examples, our “irregular” “無” from strip #2 does not seem quite so extraordinary.

If we are going to evaluate whether the “無” on strip #2 is in fact an aberration, then we need to determine if a single scribal hand is responsible for the whole manuscript, and if so, survey how that hand typically handles this character. Although creating a proper profile of graphic variation for the Peking University Laozi is beyond the scope of this article, I have found no evidence for different scribal hands in the manuscript.Footnote 87 There are eighty-six instances of “無” in the Peking University Laozi manuscript by my count. Among these eighty-six instances, there are numerous examples of “無” from the Peking University Laozi that compare especially favorably with the character under dispute, found throughout the entire manuscript, including also: 19.1; 19.3; 25.1; 56.1; 59.1; 71.3; 76.1; 77.1; 129.1; 148.1; and 149.1. Other instances of “無” exist whose bottommost component alone is comparable, or whose forms are more ambiguous, but I have not included them here. While the examples raised above do not comprise an overwhelming majority, they do prove that, for this scribal hand, the “無” written on strip #2 is by no means a solitary anomaly. In my view, Xing Wen therefore has not introduced sufficient evidence that the writing occurred after the break in this bamboo strip.

While Li Kai argues that the calligraphic variation Xing identifies between his examples of “無” on strip #1 and that of “無” on strip #2 was artistically permissible in the Han, Yao Xiaoou—like myself—instead focuses on the issue of representativeness in Xing's argument.Footnote 88 Yao mentions that the handwriting for this scribe tends to slant toward the upper right in overall character construction—which Han Wei also documents in his early introduction of the Peking University Laozi.Footnote 89 He also argues that the “無” found on strip #1 are unusual in their final stroke; namely, they all finish with an elongated sweeping na 捺 stroke, while most other instances of “無” in the Peking University Laozi (including that on strip #2) finish with either a dot dian 點 stroke or a shortened form of the na 捺 stroke. Yao thus finds Xing's examples inappropriate for a comparison.

In Xing Wen's latest article, a response to Yao, he does address the issue of representativeness.Footnote 90 Xing contends that the “無” on strip #2 angles dramatically away from the break in the bamboo in its bottom-right quarter, to a degree unexplained by the overall orientation of the handwriting on the Laozi manuscript slanting toward the upper right. Moreover, he claims that Yao overlooks how the brushwork to this character seems to be aborted for those strokes that approach the break (and not just the final stroke). That is to say, the “intention of the strokes 筆意” is unusual for “無” on strip #2, whereas the examples of “無” on strip #1 are more in line with the rest of the manuscript, including in their final strokes. I invite the reader to survey the instances of “無” I have listed above with these additional points also in mind; I myself maintain that the “無” on strip #2 will be found unexceptional.

The above analyses assume that the character for “無” on strip #2 is not missing any ink due to the break. Even if one is unable to observe strip #2 in person, a closer look at the magnified photograph provided in Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er] shows a shift in coloring to the bamboo near the edges of the tear, which alerts us to the potential that “無” here is incomplete.Footnote 91 It is possible that there is surface damage to the strip.Footnote 92 The top-down, two-dimensional photographs of this break would hide such three-dimensional aspects. If the Peking University manuscripts are authentic, then they were not only subjected to the harsh conditions of a tomb environment, but were also handled by looters, transported to an antiquities dealer, and stored for an indefinite amount of time in an unknown fashion, all of which could have caused significant damage to the strips.Footnote 93

-

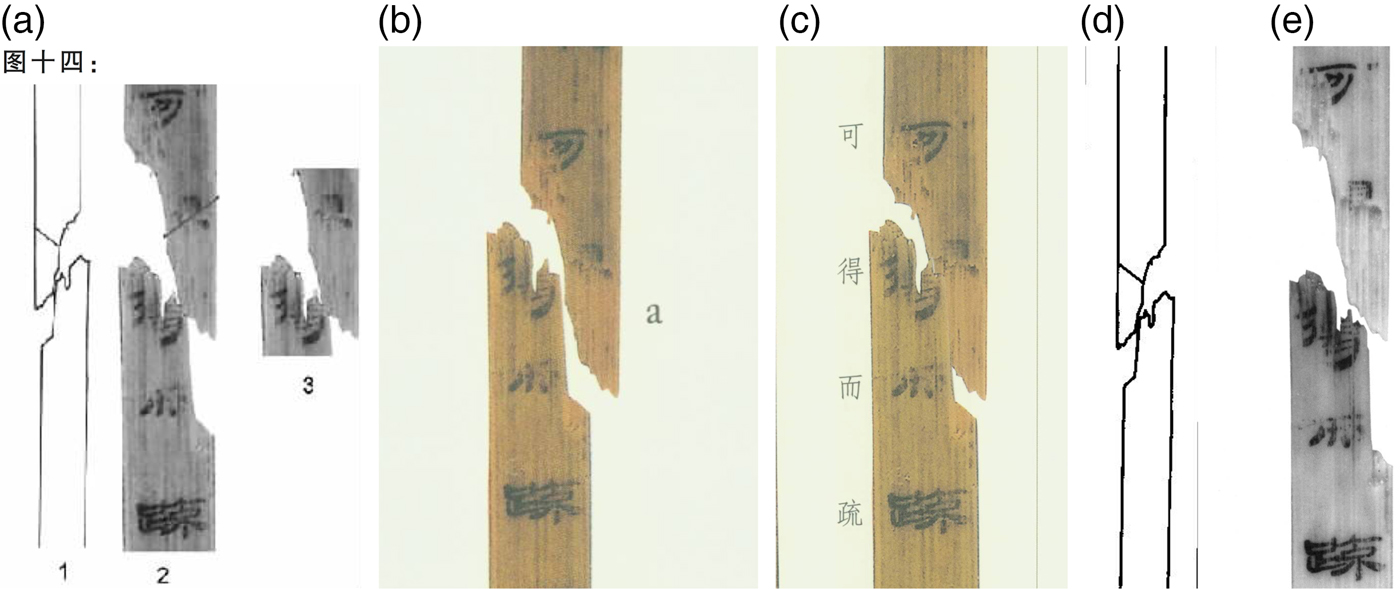

2. Following Xing's new reconstruction, the character “得” on strip #52 is shown to be an impossible form.

I am skeptical of Xing's argument concerning “得” for two reasons. First, his re-piecing of the two halves to strip #52 is untenable. For reference, see Figures 5a–e below, which shows how Xing believes the pieces should be combined (5a), juxtaposed with the presentation of the pieces in the Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er] publication (5b–e). In short, Xing utilizes the Peking University editors’ hand drawing of the verso marks (5d) and the positioning in the infrared photographs (5e), where the two pieces of #52 are presented as separated with more vertical space than appears on the photographs of the recto in their original size (5b) and magnified (5c). Xing seems to prefer the hand-drawing arrangement because it aligns the top edge of the bottom piece with the line-like verso mark found on the top piece. He then speculates that the editors, realizing this arrangement mangles the “得” written on the recto, decided to present the strip closer together in some of the recto photographs, even though this was inappropriate.

Figures 5a–e. (color online) Various presentations of “得” on PKU #52 (5a: Xing Wen's reconstruction, after “Beida jian Laozi bianwei,” image 14; 5b: Original-sized photograph after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 9; 5c: Magnified photograph after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 49; 5d: Hand drawing after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 112; 5e: Infrared photograph after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 108).

Following the hand drawing for the positioning of the strip pieces is problematic however, not just due to the overlooked verso mark on the bottom piece of strip #52 mentioned before, but also because it would throw the notches and gaps in writing for the binding strings out of alignment.Footnote 94 When considering how the manuscript was actually bound together—that is, the relationship between the positioning of neighboring strips—evidence pertaining to the binding strings themselves should take precedence over any other criteria, when that evidence is available. In the Peking University Laozi manuscript here, some wear from the string remains, there are notches carved into the strips for holding the string in place, and the writing itself seems to avoid the area where the string was intended. Xing readily acknowledges these points, when they are useful for his own argumentation.Footnote 95 In short, there is no justification for following the hand drawing's placement of the pieces when the evidence pertaining to the binding strings demands that we follow how the strips are vertically aligned in the original size and magnified recto photographs instead, evidence that Xing is fully aware of.

Once again, Yao Xiaoou has likewise questioned whether or not the two pieces to strip #52 should be positioned differently, and proposes that they are in fact overlapping as well.Footnote 96 Responding to Yao's comments, Xing argues in his latest article that we cannot however re-piece a strip based primarily on the desire to reconstitute character forms across breaks (as Yao implies), but must take into account aspects of the bamboo's materiality as well.Footnote 97 This includes an appreciation not only of how bamboo tears, but also its age and how saturated it may be with water. On these points I am in full agreement with Xing.

Xing however continues to defend his reconstructed images in Figure 5a, this time by providing measurements calculated during his technical calligraphy analysis for the width of the strip at various heights when re-pieced together in this fashion. He shows that when the top and bottom piece of strip #52 are positioned as he argues, the width of the strip is largely uniform throughout, including at the break. Xing then measures the combined widths of different locations at the break in strip #52 when it is re-pieced according to the magnified photograph's arrangement (Figure 5c), where he accuses the Peking University Laozi editors of being deceptive. Here the combined width of the two pieces at the top of the break (where “得” is written) is significantly larger than toward the bottom of the break (where “而” is written), and both areas have combined widths larger than the intact areas on either extremity of strip #52's two pieces. Indeed, in the magnified image here, it is clear that neither the far left nor far right edges of both pieces fall into alignment with one another. Because it distorts the width of the reunited strip, Xing thus argues that we cannot follow the positioning of strip #52 in the magnified photograph (where the top and bottom pieces are overlapping vertically to a large degree), but must instead follow the hand drawing (where the top and bottom pieces are only overlapping vertically to a small degree).

Xing's measurements prioritize strip width, but do not take into account total strip length. According to the “Yilanbiao” table appended in Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], the total length of strip #52, with each piece measured to its individual extremities, would equal 33.9 cm. This is nearly 2 cm more than most of the intact strips in the manuscript, which all measure between 31.9 and 32.2 cm long. This implies significant vertical overlap for the two pieces of strip #52. I have no means to accurately measure where Xing Wen positions the bottom piece in his reconstruction, however if we assume that it is flush with the verso mark (which is at 11.7 cm), then the total strip length for his reconstruction is 32.4 (11.7 + the total length of the bottom piece at 20.7 cm), which falls outside the range of acceptable lengths established by the still intact strips. Moving the bottom piece up further by 0.2 to 0.5 cm places it comfortably into this range.

What these measurements demonstrate is that there should be both significant vertical and horizontal overlap to the pieces at the site of the break in strip #52.Footnote 98 In this regard, we cannot rely on either Xing's reconstruction (based on the hand drawing, where the length is too large), or the Peking University editors’ alternative arrangement (as seen in the original and magnified photographs, where the width is too large) to be an accurate reflection of the re-pieced strip. When Xing then argues that the various components for “得” in the magnified image are still distorted (see Figure 6), he is basing his analysis on a misaligned strip.Footnote 99 While he does acknowledge the possibility of both vertical and horizontal overlap when responding to Yao's suggestion, Xing seems to dismiss the likelihood of this break occurring naturally on strip #52. He moreover wonders at how the bamboo could tear in this fashion without any signs of damage then also remaining in the same area on neighboring strips. To this latter point, note that among archaeologically excavated bamboo strips there are numerous examples in which an individual strip is damaged or split, while neighboring strips remain intact.Footnote 100

Figure 6. Xing Wen's analysis for the character “得” (after “Beida jian Laozi bianwei,” images 13.2a, 13.2b and 13.3).

In deliberating over how best to re-piece strip #52, I would remind the reader that it may be impossible to connect the pieces together perfectly, no matter how closely we may try to align them by eye or measure the strips via digital scans. Moreover, in our analysis of the character form for “得,” we must once again wonder whether ink has been lost, particularly around the “目” component. It is not surprising that pieces of bamboo broken off from the same strip do not always fit together perfectly, or that ink may be rubbed off the bamboo's surface, considering the circumstances these artifacts have endured. This leads me to the second reason I am skeptical of Xing's approach here: he is attempting to conduct a detailed analysis of character forms that occur in a heavily damaged area, an area which may be warped in ways we cannot fully anticipate, in a study where even the slightest repositioning of bamboo or ink could have significant implications. In this regard, Xing's analysis, both for the character “得” on strip #52 and for the character “無” on strip #2, is inevitably open to debate. His methodology presumes a stable textual carrier for an accurate display of writing, one which is not available in either of these areas.

-

3. The gradient of the line-like verso marks on individual strips at times appears different from those found on neighboring strips. The verso lines therefore cannot be connected uniformly across the manuscript.

As mentioned earlier, the hand drawings on which Xing Wen bases his argument do not necessarily accurately reflect the actual placement of a verso mark on an individual strip. This is because the hand drawings relied upon measurements for the verso marks that were unavoidably imprecise, as they were rounded off to the nearest tenth of a centimeter. This rounding effect could at times produce an illusion of variance that is larger than how the gradients for the line-like verso marks actually display on the artifact. Moreover, errors may have been made, both in recording the measurements and in producing the hand drawings. Since we cannot appeal to more accurate data however, other explanations should be sought to explain the misalignment.

Aside from a brief reference to the hypothesis raised by Han Wei 韓巍 in the Peking University Laozi volume, Xing Wen does not engage with scholarship on the verso mark phenomenon which has accumulated over the past few years.Footnote 101 This body of work suggests that there are other explanations for why the gradient of individual verso marks may not always be consistent and form one longer cohesive line that runs across neighboring strips. In Sun Peiyang's groundbreaking article in 2010, multiple different possibilities were already offered for how the creation of verso marks (carving or brushing) may fit into the overall chaîne opératoire for a bamboo-strip manuscript.Footnote 102 One option Sun raises is that the marks were carved or drawn onto pre-fashioned strips, either before or after writing occurred. If this is the case, then the strips would have been laid out next to one another while a knife or brush was then run across them to give the line-like effect we see on the versos. Sun, in the 2010 article, had already noted that any variation in how the strips were laid out for carving or brushing would then translate over onto the gradient of the line on individual strips, or where the line starts and ends on each specimen, making it seem out of alignment once the strips were later bound together.Footnote 103 Carving the verso lines in this manner would produce precisely the phenomena we are witnessing in the Peking University Laozi, and on many other manuscripts across the Tsinghua and Yuelu collections as well.Footnote 104

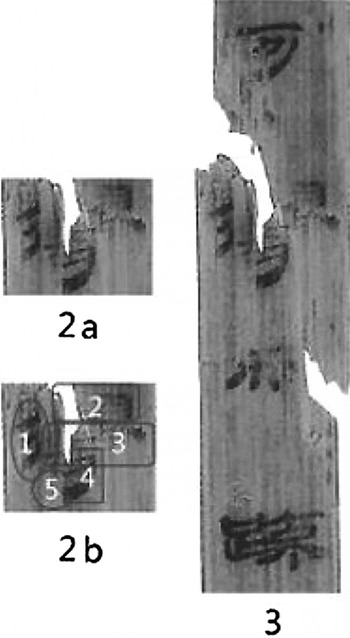

Another possibility that has recently gained more support is the “spiral line theory,” where the marks we are now seeing are carved on a tube from the bamboo culm before the strips themselves have been individually split, creating a single spiraling line that might overlap on one or two strips.Footnote 105 This is what the Peking University editors believe happened with the Laozi manuscript in their collection. Leading them to this conclusion is the fact that certain strips have “parallel lines” of verso marks, but oddly enough at these points the gradients of the lines seem to diverge dramatically from neighboring strips. They realized that overlapping slanting verso lines were not carved continuously across the entire manuscript, but rather that at these junctures they actually connected backwards to a previous strip, thereby delineating one coherent but isolated set.Footnote 106 Take for example the set of Laozi strips #71–86 in Figure 7 below (which is compared with the set of strips #87–100). The topmost verso line on strip #86 does not connect readily with that of #87, as Xing Wen points out. It does however appear to connect smoothly back to the topmost verso line on strip #71. Similarly, if we were to place strip #86 before #71, the bottommost verso lines (of the “parallel” set) on these strips would be in alignment.Footnote 107 The best way to understand this phenomenon is to think of each such set of strips connected together in the shape of a cylinder (as opposed to laid flat), with a spiral line running around it. This suggests to the Peking University editors that the carving actually took place on the bamboo culm itself. Coincidentally, when we measure the widths of strips in these “sets” of verso marks, we find that the total correlates well with the circumference of a typical Phyllostachys culm, offering further confirmation of the Peking University editors’ theory.Footnote 108 In questioning the gradient of strip #86 vis-à-vis strip #87, Xing mistakenly conflates two separate sets of strips.

Figure 7. Peking University Laozi verso, strips #71–86 vs. 87–100 (after Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], 113).

It is perhaps more difficult to justify why the gradient of the verso lines may be inconsistent across strips from within the same bamboo culm set in this model. An unsteady hand carving or drawing around a circular tube would result in variations in how the line runs, particularly if a ruler or other tool was not used.Footnote 109 With a knife, having the blade lodged into the bamboo culm might help guide the hand however, stabilizing the cut as it was twisted around the tube. There is some evidence of “curving” in the line-like verso marks across multiple strips, though this is harder to discern on any given individual strip, and would not lead to the obvious gradient shifts we see in the hand drawing of the Laozi manuscript.Footnote 110 The lines might also have been formed via multiple cuts, that is, when the blade is lifted to turn around the culm, and then pressed into the bamboo to cut again. This process would give more subtle gradient shifts, but there should be consistency across the length of a single blade stroke, without varying each strip.

More importantly, we once again cannot assume that the textual carrier we now possess is a pristine representation of its original condition. If the tube itself was first marked, then strips would need to be split from it, dried out, and otherwise manipulated. The splitting might entail splintering and loss of material, thereby creating some of the vertical misalignment we witness between the beginning and end of neighboring strips’ verso marks.Footnote 111 As for the varying line gradients, the act of “killing the green 殺青” or whatever else was done to process the strips might have potentially caused them to morph. This is not to mention any additional damage that could have befallen the strips during their time in the tomb (where they became waterlogged and structurally unsound), or if they were roughly handled by looters afterward. Warping to the strips undergoing such processes could very well impact how the verso lines appear to run, as evidenced by the mark on strip #183 compared to neighboring marks, as discussed before.

By way of supplemental proof, we may also consider examples of archaeologically excavated manuscripts that include pictures drawn in ink on the rectos of strips, and see how the ink lines might have morphed alongside the textual carrier over time, assuming as Xing does that connected lines were the scribe's objective. See for instance the Zhoujiatai 周家臺 Qin period Rishu 日書 Xiantu yi 綫圖一 drawing (Figure 8).Footnote 112 I have highlighted in the second image the top section of strips #165–67 as one example.

Figure 8. Zhoujiatai Rishu Xiantu yi, with the top section of strips #165–67 highlighted (after Guanju Qin Han mu jiandu, 44).

In a number of places in this drawing, strips are positioned so that some of the ink lines run continuously, while at the same time other lines on those same strips are impossible to connect directly across neighboring strips. That is to say, no matter how you try to position the strips, there is no way to force all the ink lines to accord perfectly across the entirety of the manuscript; the spacing and at times the gradients of the lines both shift. It is possible that the strips have morphed, leading to the misalignment now evident.Footnote 113

In both production processes hypothesized above, application of the line-like verso marks may occur before writing and binding take place.Footnote 114 A number of possibilities thus arise to explain inconsistencies between the continuity of a verso line and how the strips are arranged into a longer manuscript, particularly in reference to the text on the recto. Once a set of strips was marked, sometimes only portions of that set may actually be written upon, with the rest of the set possibly used elsewhere in the manuscript or not at all (resulting in various gradients or shorter sets respectively); individual strips might be broken or lost in the production process and thus not used (resulting in “skips”); or the initial order for the set when it was marked might be rearranged or even reversed as the manuscript is finalized for writing (resulting in “reverse-angled steps”), and so forth.Footnote 115 That is to say, it is entirely possible that conspicuous variance between the line gradient of any two individual strips’ verso marks might also be the result of strips being rearranged or inserted after the production of the marks, and before writing or binding took place. This observation is also particularly relevant to Xing's critiques (4) and (5) below.

-

4. If the verso lines are connected as closely as possible, then the bound manuscript would display strips at varying heights, which differs from what we know of early Chinese bamboo-strip scrolls.

In Li Kai's response to Xing Wen's critique, he questions the assumption that the strips of a bounded bamboo-strip scroll need necessarily be of the same length. He points out that the Guodian 郭店 Laozi 甲 (I) manuscript—among others—includes a few strips noticeably longer or shorter than their neighbors, highlighting for example strip #2 in relation to strip #1, #3, and #4.Footnote 116 Xing concedes that not all scrolls bound together strips of the exact same size. He argues however that it is unfair to compare the Peking University Laozi with the earlier Guodian witness, as the former represents a polished and complete classical treatise from the Han, whereas the latter is merely “jottings 記” from the Warring States, and therefore they differ both in genre and dating.Footnote 117 Whether or not we should accept this classification of the Guodian Laozi manuscripts, or more broadly speaking assume that a substantial difference in strip selection and binding practices occurred between these periods and genres, deserves further research. Xing nevertheless asserts that the Peking University Laozi strips’ heights vary to a significantly larger degree than what we see at Guodian, making it an entirely different phenomenon. He estimates that Guodian Laozi (I) strip #2 is 0.2 cm longer than strips #1, #3, and #4, with the standard length for the manuscript's strips given at 32.3 cm.Footnote 118 Judging from the data provided in the “Yilanbiao” in Beijing Daxue cang Xi Han zhushu [er], the height difference in Xing's reconstruction for the Peking University Laozi strips #32 and #33 is around 1.9 cm, while that for #53 and #54 is 1.8 cm, with the typical strip length again around 32 cm.Footnote 119

In evaluating Xing's claim, it is important to distinguish between strip length and strip height, the latter being the relative positioning of strips vis-à-vis one another in the final bound manuscript. As I mentioned previously, a survey of the Peking University Laozi “Yilanbiao” reveals that the lengths of all intact strips fall in the range of 31.9–32.2 cm, a range similar to that which Li Kai has pointed out for the Guodian Laozi.Footnote 120 The height difference that Xing calls into question has nothing to do with the actual lengths of the strips, but rather concerns how he imagines the bound manuscript was arranged. Namely, Xing repositions the strips so that the line-like verso marks connect as closely as possible. As I have noted earlier, however, this is not an accurate reflection for how the manuscript would have been bound in antiquity. The correct arrangement of the strips should follow an alignment of the notches and traces from the binding string, as depicted in the recto photographs, for which there is then no significant discrepancy in the strip heights.Footnote 121

Since the difference in height Xing Wen notices occurs rather with the positioning of the verso lines, we again must ask why variance would exist in this feature. If we disregard the overlooked verso mark later discovered on strip #32, one possibility is that this is the insertion of a single strip within a larger coherent set.Footnote 122 For the shift in height between #53 and 54, again we have the placement of one independent set of strips next to another. Indeed, this is the precise logic Han Wei employs to justify his presentation of the hand drawings for the Peking University Laozi verso marks, a logic which Xing ignores when he claims that the editors manipulated the data.Footnote 123 Thus, strip #53 must be separated from the neighboring strips beginning with #54, as this is the boundary between two completely different sets of strips (as marked on separate tubes of bamboo culm beforehand); the verso lines on strip #53 connect back instead with those on strip #35, hence that set is shown together. Xing's reconstruction of the strip heights disregards the “spiral line theory” under which the Peking University editors were explicitly operating, and he assumes continuity between what are ultimately two completely different verso lines. In this way, and contra Xing's criticisms, Han Wei's hand drawing helps readers appreciate an important codicological unit in the Laozi manuscript, as Thies Staack has convincingly argued we should treat such sets.Footnote 124

-

5. Strips #84 and #187 do not bear any verso marks, and yet fit into a set where the line is otherwise complete.

Figure 9. Xing Wen's rearrangement of the Laozi strips #19–34 and #48–67 (after “Beida jian Laozi bianwei,” images 6 and 7).

Xing Wen believes that, contrary to the Peking University Laozi editors’ conjecture, the manuscript was bound first and written on afterward, as evidenced by how the writing avoids the spaces where the binding string was laid. If that were the case, he finds it difficult to agree with the Laozi editors’ explanation that, during the act of writing on these two strips, an error was made and the strips discarded and replaced, all before binding.Footnote 125 For the sake of argument, let us assume that Xing's observation about the manuscript being “bound first and then written upon” is correct. We must note however that even if writing seems to avoid the spaces where binding strings were positioned, this is not in itself enough proof that binding occurred before the writing. With notches carved into the strips, it would be possible for a scribe to anticipate where the binding would occur, and leave spaces in the writing around the notches’ location, a point which Han Wei explicitly raises to defend his “writing first and then binding” position.Footnote 126

Other explanations are possible however for why the verso lines seem to “skip” in places, leaving an otherwise blank strip to fill in the gap. Han Wei has already suggested for instance that the verso marks were not applied uniformly.Footnote 127 The knife could have failed to cut as deeply or visibly here as it did in the neighboring areas, perhaps due to an imperfection in the culm, or just the unsteadiness of the craftsman's hand. In my opinion, a more convincing argument, however, is that the chaîne opératoire for a bamboo-strip manuscript was more complex than Xing Wen seems to believe. Must we imagine marking, writing, and binding as happening only in a static three-step process? The production of these manuscripts could have been much more dynamic, with each of the steps of marking, writing, and binding occurring in multiple stages and at multiple times over the life of the manuscript, from its initial production, to its consumption, and then eventual disposal.

It is possible, for instance, even assuming Xing Wen's “binding first and then writing,” that after these portions of the Peking University Laozi were initially bound (which might not have been at the same time as the rest of the manuscriptFootnote 128 ), a mistake was still made when copying out the text (as the Peking University Laozi editors hypothesize) or more likely the strips were broken while the scroll was being handled, dictating that the strips then be removed, replaced, then rebound and rewritten (in either order).Footnote 129 This would allow for an initial binding as Xing supposes, while also explaining how an extra strip with a blank verso could have been inserted into an otherwise uniform set of neighboring strips.

Interestingly, the Shuihudi Rishu 日書 daybook甲 (I) manuscript may offer confirmation that this phenomenon is in fact attested on archaeologically excavated bamboo strips, and thus is not necessarily a sign of forgery (Figure 10).Footnote 130 On the versos of strips #102–6, a series of marks runs across the bottom third of this set. Strip #104 however does not have a mark where one would expect it to be, should the pattern established from #106 -> 105 -> 103 -> 102 be completed. As a codiocological unit, this set of verso marks seems to correlate with the beginning of the text “Shi Ji 室忌” on the recto, up through the first section of the “Tu Ji 土忌,” in the first row at the top of the strips, further supporting the hypothesis that the strips were selected together as one batch in the preparation of the manuscript.Footnote 131

-

6. The top piece of strip #52 has a verso mark, while the bottom piece does not.

Figure 10. Versos of strips #102–6, with a close-up of strip #104 (after Shuihudi Qin mu zhujian, 111).

Ignoring my own observation of the strip and the overlooked presence of a verso mark on the bottom piece of strip #52, I would once again question whether this uncommon feature is necessarily proof of forgery. There are numerous other explanations for why a verso mark may be missing on only half of a strip, especially near an area with a break. It could be that surface layers of the bamboo were lost, along with evidence of a verso mark. It might be, as Han Wei suggested before, that in carving this line the craftsman erred and missed a portion of this one individual strip. Perhaps one blade cut only ended halfway on the strip, and then carving continued where the next strip was then fashioned. If additional polishing or finishing was done on the strip after the verso marks were carved, this would also erase evidence of their existence, though this is an unlikely explanation in this one instance.Footnote 132