The history of Romano-Frankish chant is full of thresholds beyond which we cannot safely tread.Footnote 1 Before the earliest Mass antiphoners, from the late eighth century, we cannot pronounce on the content of a Gregorian chant repertory. Prior to the earliest Carolingian tonaries and music theoretical writings we cannot draw conclusions about the nature of the melodies being sung, nor can we discuss melodic shapes without the neumes which first appear in the second quarter of the ninth century. The same can be said before and after the adoption of graphic technologies for notating discrete pitch.

Among the many surviving books which function in this way for modern scholarship, as epistemological boundary markers, are two celebrated volumes from the Swiss monastery of Sankt Gallen. The cantatorium Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 359, from the late ninth or early tenth century, is one of the two earliest fully notated sources of chants for the Mass;Footnote 2 and with an equivalent status for the chants of the Office is the late tenth-century Hartker Antiphoner, Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Codices 390 and 391, named after the reclusive scribe whose portrait adorns its frontispiece.Footnote 3 Quite understandably, both volumes have attained modern reputations as authoritative, even archetypal witnesses to the textual and melodic content of Romano-Frankish Chant.Footnote 4 Both have also come to be closely associated with the authorising figure of Pope Gregory the Great.Footnote 5 But whereas the former volume gained that status in the throes of nineteenth-century chant reform, the Hartker Antiphoner exuded a palpable ‘Gregorian’ legitimacy from the outset. Its opening pages bear not only an iconic illustration of Pope Gregory dictating chant melodies to a scribe as he receives them from a dove, the earliest and most famous instance of that tradition of musical iconography, but also a poem on the facing page which projects similar ideas in verse.Footnote 6 Thus this book places the scholar in an interesting methodological bind. Its status as the ‘earliest’ witness has elevated it to a place of towering authority, an authority which is amply reinforced by the book’s conscious self-presentation as authentically ‘Gregorian’. Yet by virtue of its earliness we are also deprived of the necessary means to challenge or dissect that historiographical status. Since medieval chant books are now but the fossils of once-living musical traditions, there is always a scholarly imperative to investigate behind and beyond the written materials which we possess. For this extraordinarily fêted volume, however, the product of a monastery which is itself an outsize presence in chant historiography, that need is especially acute.Footnote 7

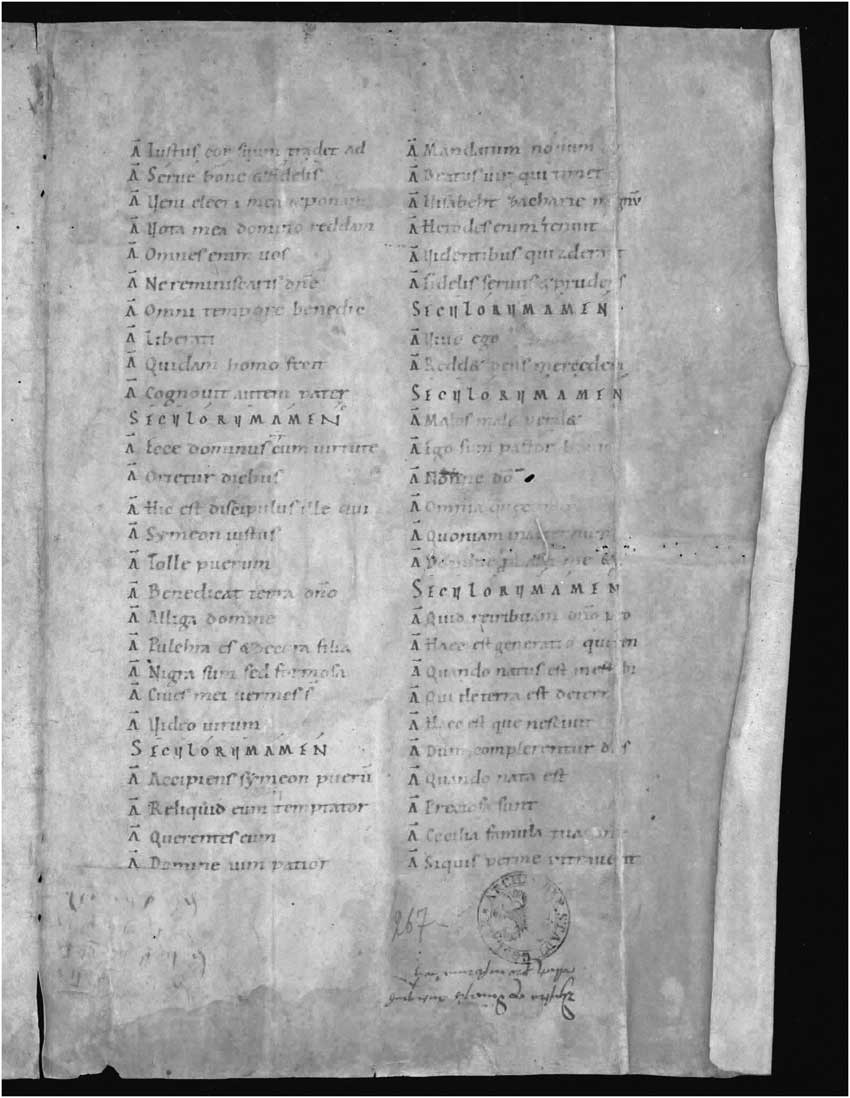

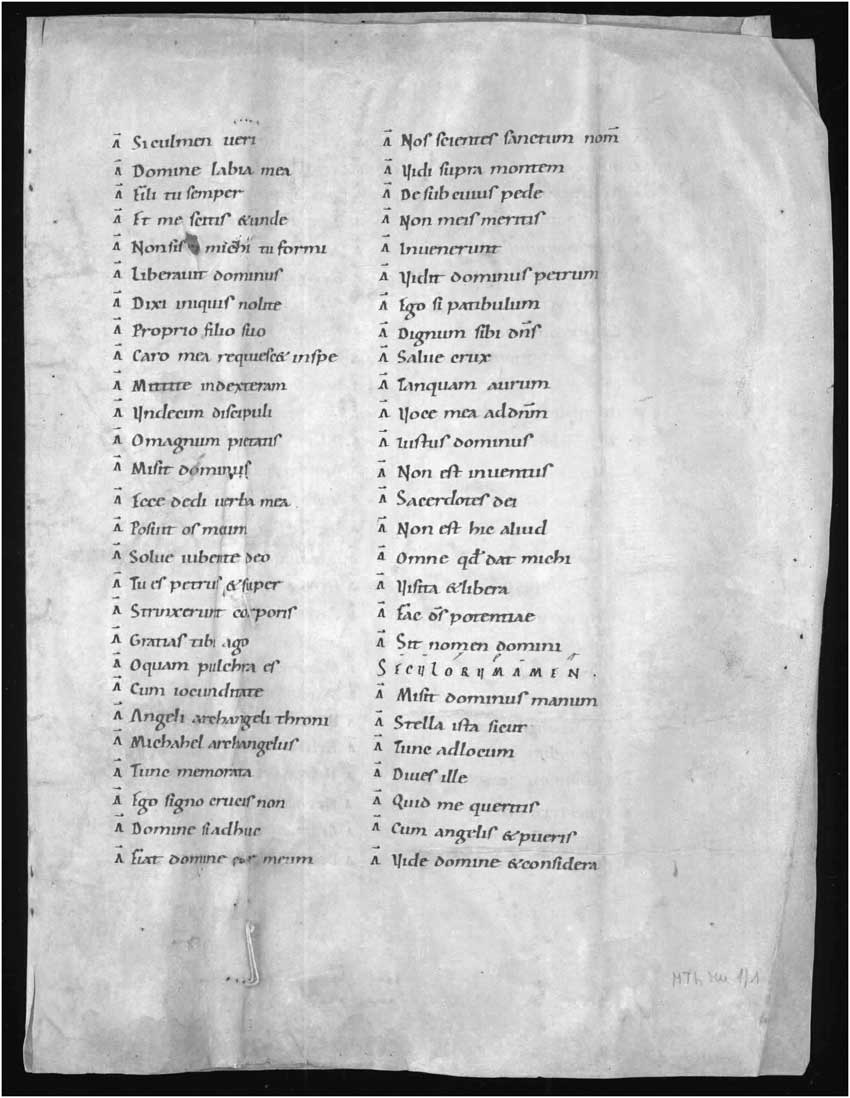

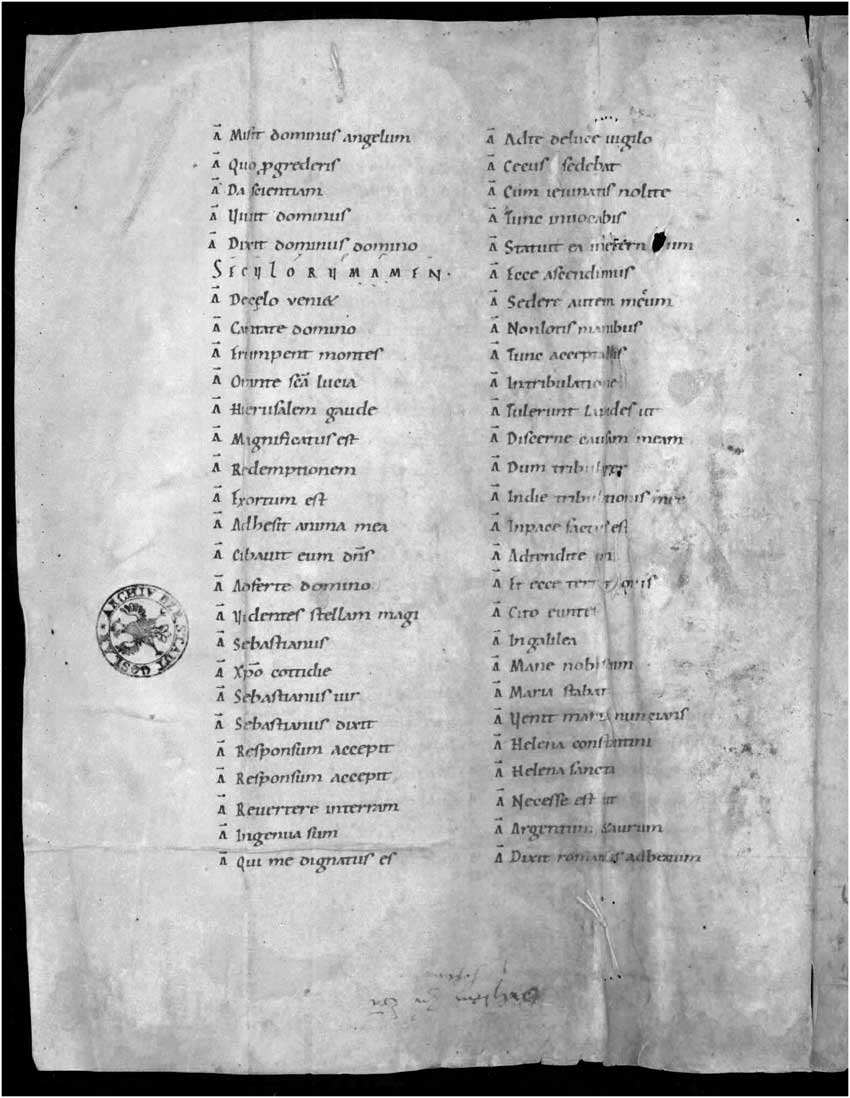

Enabled by a hitherto unpublicised Office book fragment from Sankt Gallen, this article attempts to peer behind the facade of the Hartker Antiphoner. The document in question, Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1, is a single, partially notated bifolium from what was once an Office tonary, which is to say, a book of chant incipits ordered not by liturgical place (as in an antiphoner) but by melodic classification.Footnote 8 The basic function of this book was to group Office chants by mode, and to further categorise antiphons by their differentia, that is, the recommended melodic formula for the ‘saeculorum amen’ at the termination of the doxology, whose correct employment facilitated a seamless return to the antiphon’s repeat. In this instance, our tonary was also probably designed to communicate the Office repertory at Sankt Gallen in toto. The four surviving pages list some two hundred items, tabulated in the Appendix below, corresponding to approximately one-third of the Sankt Gallen Office chants assigned to the third and seventh modes.Footnote 9 (A full reproduction is included at the end of this article, Plates 1–4.) A palaeographic dating to the first or second third of the tenth century, if accepted, makes this fragment comfortably the earliest surviving Sankt Gallen tonary, as well as the earliest witness of any substance to the Office repertory of that monastery.Footnote 10 It also places these leaves in a celebrated period of musical activity at Sankt Gallen, one which has also been noted – but perhaps need not be noted any longer – for the apparent lack of music theoretical engagement.Footnote 11 The very fact of its existence clearly deserves wider exposure, and it means that several small thresholds in chant historiography must move accordingly.

However, arguably the greater significance of this fragment derives not from its contents per se, but from the manner in which it complements other surviving materials, helping us to address larger questions about the shape of the early Office liturgy at Sankt Gallen. Henceforth referred to as the Goslar Tonary, this document will be shown to be a slightly grander relation of the more famous tonary from tenth-century Sankt Gallen, that is, the set of palimpsested bifolia which now share their bindings with the Hartker Antiphoner. This so-called Hartker Tonary was reconstructed by the Solesmes monks in their Paléographie Musicale facsimile a century ago, and its relationship to Sankt Gallen and wider practices was scrutinised in detail as part of a larger tonary study by Ephrem Omlin.Footnote 12 These efforts notwithstanding, Jacques Froger noted in 1970 that a proper comparative study of the Hartker Antiphoner and Tonary remained to be accomplished.Footnote 13 That call has gone unanswered in the half century since.

This study is not the last word on that relationship, which would require a book of its own, but rather it is an attempt to place some of the larger historical pieces together. This is now possible in a way that it was not for Froger, thanks to sustained work in recent decades on Sankt Gallen’s musical, scribal and notational accomplishments before the eleventh century.Footnote 14 In a particularly valuable overview of liturgical codification at Sankt Gallen in this period, with attention directed primarily towards the music of the Mass, Susan Rankin advanced the significant claim that ‘we can perceive the major liturgical task of the tenth century [at Sankt Gallen] as the cultivation and secure recording in script of a “home” liturgy, with all its Roman and Frankish, old and new, foreign and native, dimensions’.Footnote 15 This has yet to be demonstrated for the Office, and so the unearthing of the Goslar Tonary represents an obvious invitation to re-evaluate that claim. More generally, a parallel assessment of the Goslar and Hartker Tonaries, along with some other Sankt Gallen fragments, permits us to establish a new, more broadly contextualised view of the early Office chant repertory at this institution. Above all, it provides the means to look again at the celebrated and now-ubiquitous work of Hartker.

the pre-history of hartker

There has never been any doubt that Hartker’s Antiphoner stood upon earlier layers of chant practice at Sankt Gallen. The only question is how faithfully it reproduced its musical past. According to the monastery’s eleventh-century historian Ekkehart IV, the local chant repertory had a claim to be authentically Roman. In a marginal embellishment to the Sankt Gallen copy of John the Deacon’s hefty Life of Gregory, Ekkehart told the tale of ‘Romanus’, a Roman cantor who brought his Roman antiphoner to the monastery in the late eighth or early ninth century.Footnote 16 He also made the point a second time, as part of his continuation of the monastery’s historical record, the Casus sancti Galli.Footnote 17 The same idea of Roman authority was of course embodied in the opening pages of the Hartker Antiphoner, a book with which Ekkehart cannot but have been familiar, and this author gave further weight to the premise in his Liber benedictionum when he affirmed the responsibility of Pope Gregory for Frankish chant.Footnote 18 Nine hundred years later, René-Jean Hesbert articulated a remarkably similar view of Sankt Gallen’s musical authority when he identified the Hartker Antiphoner as the oldest of seventeen Office chant manuscripts which he considered closest to a lost Roman archetype.Footnote 19 In an earlier volume Hesbert reached a more mainstream conclusion, that the Hartker Antiphoner was a ‘hybrid’ of ‘somewhat indecisive’ nature, but within the parameters of his investigation this book was still essentially as authoritative as they came.Footnote 20

However, it appears that neither author had counted on the evidence of fragments. Whatever truth there might have been to the ‘Romanus’ legend, its relevance to Hartker is greatly undermined by the survival of two chant folios from later eighth-century Sankt Gallen, now SG 1399.a.2.Footnote 21 Copied by the scribe Winithar, these pages attest to a world of chant singing at odds with later Sankt Gallen antiphoners. There are some textual concordances, to be sure, but nor can there be any doubt about the existence of discontinuities. The Purification responsory Tolle puerum et matrem eius (p. 1; CAO 7768), for instance, agrees with two ninth-century Frankish antiphoners and the Old Roman tradition, but was not preserved in later Sankt Gallen sources, nor is it known to have been copied anywhere else except in the shape of an antiphon (CAO 5156).Footnote 22 As Rankin has argued on the basis of such evidence, we are probably witnessing the effects of Carolingian editorial activity during the ninth century, something from which Sankt Gallen was clearly not immune.Footnote 23 In other words, the Hartker Antiphoner is at best a foggy lens into this eighth-century musical past.

Rather more contentious is where Hartker stands in relation to the later Carolingian period. In the wake of the various interventions recommended by ninth-century figures such as Agobard and Helisachar, to cite two individuals whose names we know, we would tend to expect a greater degree of stability in Sankt Gallen chant practices as the ninth century gave way to the tenth.Footnote 24 After all, this was the age of the now-celebrated pair of graduals SG 359 and Laon, Bibliothèque municipale 239, separated by their geography and notation yet remarkably concordant in their musical and textual testimony.Footnote 25 But once again fragments cast doubt on such an assumption.

Although palaeography has not been able to pin them definitively to Sankt Gallen, the late ninth-century endleaves of SG 86 (pp. 1–4, 231–4) communicate a chant repertory which is not only largely concordant with the Hartker Antiphoner, but which also aligns certain key chant texts to the same liturgical functions as they are found in Sankt Gallen a century or more later.Footnote 26 Examples include the Advent Sunday Magnificat antiphon Ecce nomen domini (p. 1; CAO 2527) and the Epiphany Magnificat antiphon Venit lumen tuum (p. 233; CAO 5344). But these leaves do not represent a simple foreshadowing of Hartker by any stretch. Most strikingly, they embody a strange liturgical contradiction. While the surviving pages encompass chants and readings for major Office services (Vespers, Matins and Lauds) on major Sundays or feasts (Advent, Holy Innocents, Circumcision, Epiphany, St Sebastian and St Agnes), their content is actually more befitting of an ordinary weekday. In place of the great responsories at Matins we find short responsories, of the sort which in the Hartker Antiphoner are rubricated as responsoriola; and rather than the customary sequence of nine or twelve Matins antiphons for feasts, the pages provide only the canticle antiphons for Vespers and Lauds and the invitatory for Matins.Footnote 27 Where present, the Matins readings are also unusually short. The liturgical rationale still remains to be worked through, but it is transparently not what we are accustomed to find in later books. Added to this is the lingering spectre of Winithar. The short responsories Vox de caelis sonuit and Caeli aperti . . . vox patris audita est (p. 3) are unknown in any later source, the former resembling an antiphon of the same name (CAO 5507), the latter now better known as the verse for the responsory Hodie in Iordane (CAO 6849). And among the antiphons is the Gallican composition Insignes praeconiis (CAO 3355) for St Sebastian, a chant which would never be seen again at Sankt Gallen, nor in Swiss antiphoners at large. Once again, then, the Hartker Antiphoner comes across as a strangely distant cousin.

Even tenth-century sources from Sankt Gallen could differ from Hartker’s imprint, as Walter Berschin, Peter Ochsenbein and Hartmut Möller showed in a collaborative study of the office for St Otmar, one of the monastery’s lesser patron saints.Footnote 28 By comparing the Hartker Antiphoner with the music in book of hagiography from early tenth-century Sankt Gallen (Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf. 17.5 Aug. 4o), the authors were able to posit that the St Otmar office had existed in two versions prior to the copying of the Hartker Antiphoner, after which further chants were also appended. The key witness for their narrative was our friend the local historian Ekkehart IV, who also documented further tenth-century additions to the Sankt Gallen repertory in honour of St Andrew and St Afra.Footnote 29 Clearly the fluidity of local saints’ offices at Sankt Gallen should not be projected outwards onto the Romano-Frankish repertory at large, but these instances of local tenth-century change are crucial for the deductions to be made below.

The other key precursor to the Hartker Antiphoner is the fragmentary tonary with which it now shares its bindings, a document widely thought to represent a slightly earlier Sankt Gallen tradition. (I shall substantiate that claim below.) Dismembered and partially palimpsested during the thirteenth century, probably in connection with the division of the manuscript into its present two-volume state, this so-called Hartker Tonary shares with the antiphoner a near-identical repertory of Office antiphons, whose ordering within melodic categories is not alphabetical (as is sometimes the case in tonaries) but liturgical, in a sequence which is itself closely aligned to the antiphoner.Footnote 30 The shared repertory includes chants for the local patrons St Gall and St Otmar, as well as some of the aforementioned chants for St Afra and St Andrew. Given that chant repertories for the Office are so much more variable than those for the Mass, both in contents and in ordering, this is a very solid relationship. No less importantly, the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner share a similar set of melodic assignments for both mode and differentia. Also common to both is the use of ‘Tonarbuchstaben’, or tonary letters, a shorthand characteristic of Alpine and Southern German antiphoners whereby the mode is indicated with a Latin or Greek vowel (a, e, i, o, u, Η, y [υ] or w [ɷ]) and the differentia with a consonant (b, c, d, g, h, k, p or q).Footnote 31 The Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner are in fact the two earliest examples of this system, and the concomitant absence of tonary letters from the Goslar fragment suggests that the innovation may even have been contemporary with Hartker. What this means, in sum, is that these two sections of the Hartker manuscript are incontrovertibly the products of the same late tenth-century institution.

Indeed, Froger went so far as to suggest that the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner shared a scribal hand, albeit not necessarily the famous eponymous scribe, whom he determined to have been working within a small team of copyists.Footnote 32 Huglo and Omlin were both more circumspect about the palaeographical relationship,Footnote 33 but in a more recent study of the manuscript’s notations Kees Pouderoijen and Ike de Loos were able to uphold Froger’s claim.Footnote 34 According to the authors, the neumes in the Hartker Tonary were probably the work of the manuscript’s tertiary notator, ‘NHc’, who also had responsibility for the manuscript’s collection of invitatory antiphons as well as parts of the antiphoner proper. Neumes are not central to the tonary’s purpose, of course, and these ones may not be contemporary with the text hand. Nevertheless, we can now confirm that the different sections of the book were together in the early eleventh century. The connectedness of the sections is further attested by the fact that the twelfth-century Sankt Gallen manuscript SG 388, already known to be a copy of the antiphoner, conveys the very same invitatory antiphons and an abbreviated version of the same tonary (pp. 2–5).Footnote 35

The most interesting point about the Hartker Tonary, however, is that it is not completely identical to its adjacent antiphoner. It has a slightly different repertory, a slightly different pattern of liturgical ordering and a slightly different list of modal assignments. Although these discrepancies are not enough to cast doubt on an institutional relationship, they do constitute a crucial source of interpretative leverage, to be exploited further below when we analyse the Goslar Tonary. By the same token, however, they demand our studious attention. Besides the fact that these discrepancies have not been discussed in scholarly literature since the 1970s, they also present a series of interpretative challenges which warrant significantly more consideration here. Only once we have scrutinised anew the relationship between the Hartker Antiphoner and the first documented Sankt Gallen tonary, therefore, can we begin to incorporate the evidence of a second.

the hartker tonary reconsidered

To date Ephrem Omlin is the only scholar to have attempted a systematic comparison of the Hartker Tonary and Hartker Antiphoner repertories.Footnote 36 Although this author would have benefitted significantly from the database mentality which began to infiltrate Office scholarship in the 1960s, to say nothing of further proofreading, he still contributed a great deal, not least in his grappling with matters of methodology. The essential problem, as Omlin recognised, is that the very differences which open up a hermeneutic space between the tonary and antiphoner also obstruct definitive conclusions about their relationship. Depending on which source we think came first, a chant which is ‘missing’ relative to the Hartker Antiphoner may represent an addition or it may represent a subtraction, and it may have been made consciously or otherwise. But since neither the Hartker Tonary nor the Hartker Antiphoner survives in complete form – as it stands today the tonary lists some eight hundred antiphons, which is approximately half the Office repertory – the same evidence may also indicate a change of liturgical position, conscious or unconscious, or a change of modal assignment, the evidence of which may or may not now reside in a lacuna.Footnote 37 The situation is compounded by a litany of further problems: the fact that many (if not most) of the modal assignments in the antiphoner were added to the margins by later hands; the question of what relationship (if any) the tonary and the antiphoner were meant to have; and the open question as to whether the twelfth-century witness SG 388 (a useful source wherever the original pages of the Hartker Antiphoner are lacking) was truly a verbatim copy.Footnote 38

All of this explains why Omlin never explicitly enumerated the repertorial differences between the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner, opting to provide comparative tables and a verbal summary instead.Footnote 39 All we can really say is that there are between fifty and a hundred antiphons in the Hartker Antiphoner which are not where they ‘should be’ in the Hartker Tonary.Footnote 40 Conversely, the Hartker Tonary has no more than a handful of chants which are not in the Hartker Antiphoner. Some of these ‘missing’ chants can be explained by scribal strategy. Omlin noted how two groups of chants – the Advent ‘O’ antiphons and some two dozen sixth-mode antiphons after the model of Ipse inuocauit me – are represented in the tonary only by a handful of exemplary chants.Footnote 41 As he reasoned, this is probably not because these antiphons came in or out of favour, but because they are unusually formulaic. However, for the remainder we are forced to reckon with two basic possibilities: either the Hartker Antiphoner represented an expansion of the repertory in the tonary or, in reverse, the Hartker Tonary represented a contraction of the repertory in the antiphoner.

The question of precedence was resolved by Omlin via the feast of St Gregory, of whose chants the Hartker Tonary bears no trace.Footnote 42 That is to say, out of the five St Gregory chants in the Hartker Antiphoner which should be locatable in the tonary, not one is present. Crucially, these missing chants are susceptible to a precise dating. Although St Gregory was most famously venerated with the office Gloriosa sanctissimi, attributed to Bruno of Toul (Pope Leo IX, d. 1054), the antiphons in question actually belonged to a lesser-known South German composition of limited circulation, with first antiphon Sacerdos et pontifex and first responsory Mutato etenim. As Omlin observed, veneration of St Gregory in the Lake Constance area saw a revival during Hartker’s lifetime, first in 989 when the saint’s relics were translated to Petershausen, and then in 992 when the same monastery was rededicated to that saint.Footnote 43 To this day no one has found a better explanation for this office’s composition, and thus we have a relatively solid boundary for dating: while the Hartker Antiphoner is unlikely to be any earlier than 989, the Hartker Tonary is unlikely to be much later. Given that Hartker himself is known to have been a recluse at Sankt Gallen between 980 and his death in 1011, Omlin’s conclusion allows for the possibility that Hartker was responsible for both portions of the manuscript, perhaps over the extended period in which he was in his cell.Footnote 44

Reviewing Omlin’s findings, Michel Huglo further proposed that between the making of the Hartker Tonary (or its model) and the Hartker Antiphoner there had been an influx of West Frankish chants.Footnote 45 He also suggested that the absence of three chants for All Saints might even place the tonary’s ancestor in the years around 850, that is, prior to the adoption of that feast at Sankt Gallen. However, his readings of the situation were not entirely accurate – and here the blame is to be shared with Omlin, whose tables can be frustratingly opaque – since the Hartker Tonary actually has many chants for All Saints. Moreover, while Huglo’s example of a possible West Frankish import, Suffragante domine, is indeed documented in (later) French sources, its earliest known copies appear to be local: it is specified as a processional antiphon both in the gradual Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 121 (pp. 411–12), dated to around 960–70, and in the processional portion of SG 18 (p. 31), which Rankin has placed ‘in the early to middle years of the tenth century’.Footnote 46

In one further misapprehension, Huglo implied that the Hartker Tonary pre-dated the Sankt Gallen office chants for St Afra, whose composition Ekkehart IV attributed to his namesake Ekkehart I (d. 973).Footnote 47 There are in fact many antiphons from the St Afra office in the Hartker Tonary, which comfortably quashes speculation of an earlier tenth-century origin. But there is something insightful about the presentation of this particular office. I have already mentioned how the tonary is ordered first by classification of mode and differentia, and then by liturgical position, according to a pattern which closely resembles the Hartker Antiphoner. What Omlin found was that those chants which deviate from the antiphoner’s liturgical pattern also belong to the same handful of liturgical occasions – he named Trinity and St Afra, but he should also have added St OtmarFootnote 48 – and, moreover, these liturgical occasions also happen to be among the few feasts which are incompletely represented in the Hartker Tonary. As Omlin went on to argue, using reasoning which Lipphardt would later deploy in pursuit of a Carolingian tonary archetype, this state of disorder is best explained by the recent addition of these offices to the Sankt Gallen repertory.Footnote 49 The disorder also explains Huglo’s confusion.

At the risk of overstating the point, there is actually even more to say about the tonary’s liturgical ordering. So far unnoticed is the fact that a single antiphon from the office of St Andrew, Ambulans Iesus, is also copied out of sequence in the Hartker Tonary, residing instead among chants of the Common. This may not be a coincidence, since in his history of the monastery Ekkehart IV attributed Ambulans Iesus to none other than Ekkehart I (d. 973), the same monk who penned the out-of-place St Afra office.Footnote 50 (He also described Ekkehart I as the author of the St Andrew invitatory Adoremus gloriosissimum, which would not qualify for inclusion in the Hartker Tonary, but which does have its own anomalous presence among the book’s seventh-mode invitatories.Footnote 51 ) Putting all this evidence together, both palaeographic and repertorial, there is every reason to believe that the Hartker Tonary was a product of Sankt Gallen during the 980s. This was a period in which Hartker himself is known to have been active, when the new office chants for St Otmar, St Andrew and St Afra had recently entered circulation, but prior to the composition of a new office for St Gregory around 990.

These same offices also permit further commentary on the date of the Hartker Antiphoner. That date is now widely considered to lie in the 990s, partly on the basis of Omlin’s deductions about the Gregory office, but partly also because of long-standing speculation about a palaeographical link with SG 339, normally dated to around the turn of the millennium.Footnote 52 Here I can offer one further point of affirmation. What Omlin did not comment on was the fact that some of these compositions, already out of place within the Hartker Tonary’s liturgical scheme, would remain out of place in the Hartker Antiphoner. The St Afra office was copied into the Hartker Antiphoner after the Common of Virgins, an obvious anomaly which was acknowledged even in its own time, when at St Afra’s expected place in the Sanctorale one of the main scribes added a rubric redirecting the reader (SG 391, p. 95). Meanwhile, the Trinity office in the Hartker Antiphoner was copied not in its familiar post-Pentecost position, but among the manuscript’s ferial (per annum) chants after Epiphany. Since the Hartker Antiphoner has no Trinity Sunday celebration, but instead provides for the older feast of the Pentecost Octave, it follows that in late tenth-century Sankt Gallen the Trinity was still a floating, votive observance.Footnote 53 Hence there follows an interesting implication for the similarly out-of-place St Afra office. According Emmanuel Munding’s survey of calendars at Sankt Gallen, the first liturgical book to grant St Afra her accustomed feast-day of 7 August was none other than the aforementioned gradual SG 339, whose calendar Munding dated to 997×1011.Footnote 54 Up to that point, then, this too may have been a purely votive celebration.

There are two valuable conclusions to draw. The first is that St Afra’s office may initially have been included in the Hartker Antiphoner only because it was a local composition, and not out of any immediate liturgical requirement or need. As Rankin has already cautioned in relation to early liturgical volumes from Sankt Gallen, ‘it is important to distinguish between what the monks actually performed in the liturgy, and the content of their books . . . it is far from clear that these two matched before the eleventh century’.Footnote 55 The second conclusion returns us to the matter of dating. Given that it was one of the main scribal hands of the antiphoner who added the note redirecting the reader to St Afra’s misplaced office, it seems highly likely that the book was approaching completion when, at some point in the 990s, her feast first entered the Sankt Gallen calendars.Footnote 56 By the time of the summer breviary SG 387, which Munding dated to 1022×34, we find the offices for Trinity and St Afra assigned to their customary places in the sanctoral and temporal cycles (pp. 234, 338).Footnote 57 At this stage of the process, as Rankin’s comments would imply, provision and need had begun to be reconciled.

introducing the goslar tonary

With a detailed sense of context thus established, let us now bring the Goslar Tonary into the fold. Apparently reused in early modern times as a wrapper or binding support, the document now preserved as Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1 is a single surviving bifolium of a tenth-century Office tonary. The most recent cataloguer was not incorrect when she reported that it comprises a list of antiphons and responsories, but these pages are more sophisticated than that account would imply.Footnote 58 So far as we can deduce, the chants of this tonary were carefully arranged on four levels: first by mode, then by genre, then by differentia (antiphons only), and then finally according to the liturgical calendar. There may have been an element of taxonomic intent to this scheme, to borrow Paul Merkley’s characterisation of tonary types, since, as we shall see in a moment, the Goslar Tonary was probably conceived as a complete record of local Office chants.Footnote 59 At the same time, though, the document clearly had practical value for singers, its subdivisions by mode and differentia ensuring the smooth marriage of antiphons and psalm tones, to say nothing of the mnemonic value of a book organised by degrees of melodic resemblance.Footnote 60

Everything just written could also be said of the Hartker Tonary. Indeed, as the comparison in Figure 1 shows, our manuscript might casually be mistaken for its twin. The two sources share not only the same basic strategies of presentation, but also the very same ruling of twenty-seven lines and two columns to a page. We shall shortly see how these similarities extend also to the content and disposition of the antiphons. (Alas, the Goslar Tonary affords no opportunities to compare ‘noeane’ formulae or other distinctive details at the beginning of each modal section.) But there is also much which sets the Goslar Tonary apart. Hartmut Hoffmann found its medium-sized script to be characteristic of the first or second third of the tenth century, which puts it well out of reach of Hartker’s lifetime.Footnote 61 Moreover, the fragment’s dimensions of 332×260 mm (writing space 230×160 mm) make it some 50 per cent larger than the Hartker volume, whose page size of 220×165 mm is itself at the upper end for music books from tenth- and eleventh-century Sankt Gallen.Footnote 62 One of the pages also has a decorative initial of red and green ink, which, though not of supreme quality, is certainly more opulent than the surviving leaves of its cousin. What this means historically is hard to say at this point, but we can very easily discount the possibility that this is a missing fragment from the Hartker Tonary. We are dealing with a previously unknown book.

Figure 1 A side-by-side comparison of the Goslar Tonary (fol. 1r) and Hartker Tonary (SG 391, p. 8), showing their relative sizes

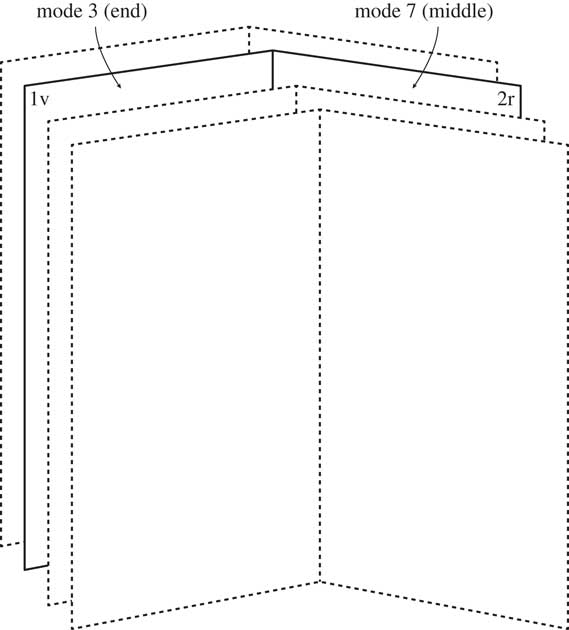

Although the Goslar pages have never been foliated, their modal content makes it easy to infer the correct sequence of texts. The first folio (as I shall now call it) comprises fifty-six antiphons and forty responsories from the third mode, while the second comprises 106 antiphons from the seventh mode, as detailed in Table 1. Because the tonary is comprehensive in its coverage of the repertory, as will soon become clear from comparisons with the Hartker Antiphoner, we can further hypothesise the size and nature of the original creation. The state of the parchment reveals all, for the disposition of flesh (1r and 2v) and hair (1v and 2r) sides means that, assuming a standard quiring, the bifolium was even-numbered. Because the text of fol. 1v is disjunct with that of fol. 2r we can further deduce that it was the second sheet of four. This arrangement is modelled in Figure 2. Given the relative paucity of Romano-Frankish Office chants in the fourth, fifth and sixth modes, a total of eight intervening pages seems exactly right for the antiphons and responsories in between. However, with significantly greater numbers of Office chants in the first, seventh and eighth modes, a single gathering could never have been enough. A back-of-envelope calculation suggests that the tonary originally spanned three quires, of which ours was the second.

Table 1 Overview of Goslar Tonary contents

Figure 2 A reconstruction of the codicological context of the Goslar fragment

In terms of the choice and disposition of differentiae, the Goslar Tonary is also a close match for the Hartker Tonary. The earlier source lacks the tonary letters which aid our navigation of the latter, but a simple comparison of the differentia notations leaves little doubt as to the relationship, as can be seen in Figure 3.Footnote 63 Despite one consequential difference between the two (the apparent reversal of the cadences for ‘ig’ and ‘ih’), this is a stable relationship when seen in its wider context.Footnote 64 For example, the delineation of six types of third-mode differentia in these tonaries can be compared to the seven in the ninth-century Metz Tonary, the five in the tenth-century Brussels tonary associated with Regino of Prüm, and the six in the late eleventh-century tonary of Frutolf of Bamberg – to say nothing of the actual differentia melodies and the nature of their relationship to the antiphons, all of which varied greatly.Footnote 65 Sparse as they are, the notations (reproduced in Figure 3) underline the relationship, for both tonaries show evidence of episemas (lengthenings) and clarifying significative letters, detailed performance directions for which Sankt Gallen’s early notators are justly famous.Footnote 66 The Hartker Tonary additionally appears to use vertical heighting to clarify the difference between the reciting note b and its upper neighbour c, which might perhaps be considered a reflection of its later date.

Figure 3 Third-mode differentiae in the Goslar and Hartker Tonaries

Ultimately, proof of a relationship between these tonaries is to be found in the chants themselves, which in certain modal categories are perfectly matched. Table 2 compares the evidence for the third-mode differentia ‘ic’.Footnote 67 But for the minor textual anomaly, considered below, the two tonaries have the same ten chant incipits for this differentia, in the same order, including the telltale antiphon Videntibus qui aderant for the local feast of St Gall. The Hartker Antiphoner does not order its chants by differentia, but by liturgical feast. Nevertheless, if we search its original layer for antiphons marked ‘ic’ we can also find the same ten chants, assigned to feasts which were copied in the same order. For reasons already explained, these are all potent signs of institutional proximity, and it is on this basis that we can speak of both tonaries as ‘complete’ records of the repertory. It should also be mentioned that the liturgical ordering shared by these sources is far from conventional. The idiosyncratic mixing of feasts from the Temporale, Sanctorale and Common which is sometimes seen as characteristically Hartkerian ought, on this evidence, to be considered a feature of Sankt Gallen practice at large.

Table 2 Goslar and Hartker Tonary chants with third-mode differentia ‘ic’

The one blemish among the concordances of Table 2 is the Goslar chant Beatus vir qui timet, which is very easily explained as a mistake. The only Sankt Gallen chant of that name is categorised in later sources as ‘yg’ (seventh mode) and assigned to Sundays per annum, which would be out of place here on both melodic and liturgical grounds. But if we go looking for Sankt Gallen chants categorised as ‘ic’ which occur liturgically between Mandatum novum (Maundy Thursday) and Elisabeth Zachariae (John the Baptist), the only option is Beatus vir qui inuentus. On that reading both the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner agree. In other words, the Goslar scribe made an honest mistake, confusing one among many Psalmic instances of ‘Beatus vir’. He would do so again, as we will see, and it is clear from a number of similar mistakes that neither he nor the Hartker Tonary scribe was immune from this kind of confusion.Footnote 68 Nonetheless, the very fact that we can arrive at an explanation is itself reassuring of the underlying relationship.

The nature of this relationship can be narrowed down even further, because in places where the Hartker sections differ and can be measured against our fragment, the two tonaries form a united front against the antiphoner. (The antiphoner’s identity now comes into much greater focus as a result, and this will be explored in detail below.) The tonaries are not identical, but their disagreement is effectively minimal: within the series of fifty or so chants and six third-mode differentia categories which can be deemed ‘concordant’ between the two, the Goslar Tonary has two antiphons to itself, the Hartker Tonary has three antiphons to itself, and the Goslar Tonary has two ‘Beatus vir’ texts out of place.Footnote 69 Within that same sample the Hartker Antiphoner has nine extra antiphons not found in either tonary. Conversely, the agreement between the tonaries is strong. For instance, whereas the Hartker Antiphoner places the ferial (per annum) antiphons after Epiphany, both tonaries concur in placing them at the end of each melodic category, after the post-Pentecost antiphons.Footnote 70 Modal classifications tell a similar story. The most striking example is the differentia later known as ‘ig’, for which the two tonaries list six antiphons – as is visible from Table 3 – but which in the Hartker Antiphoner appears to have disappeared altogether. (This fits into a documented long-term trend of differentia categories being thinned down.Footnote 71 ) Meanwhile, as Table 4 shows, those chants which in the Hartker Antiphoner are either ‘ih’ or have been corrected to ‘ik’ are undifferentiated in the tonaries. Collectively, these examples serve to corroborate the hypothesis about the Hartker Tonary’s probable precedence over the Antiphoner. They also help to underline the vital fact, easily forgotten whenever tonary scholarship turns into textual criticism, that musical understandings do not stand still for long. Different cantors could of course construe the repertory in different ways.

Table 3 Goslar and Hartker Tonary chants with third-mode differentia ‘ig’

Table 4 Goslar and Hartker Tonary chants with third-mode differentia ‘ih’

a This is undoubtedly a mistake, as explained in n. 68.

Table 4 is also important for its ability to date the Goslar fragment. The key is Post decem vero annos, a tenth-century composition for the feast of St Otmar which is absent from the Goslar Tonary but is present in the Hartker Tonary. Just as with the St Gregory office considered above, the implication is that the Goslar Tonary antedates the composition. But to make any such argument we need to tread with the utmost care, not only because of the various tonary lacunas, but also because the St Otmar office has its own complex compositional history. According to Berschin, Ochsenbein and Müller, the office went through two iterations prior to the Hartker Antiphoner: Office I, which they date to before 920; and Office II, an expansion and reworking of Office I which they attribute to Notker II (d. 975) via an ambiguous attribution from Ekkehart IV.Footnote 72 Within these two layers we can distinguish three groups of chants: (a) that found only found in Office I; (b) those from Office I which were later incorporated into Office II; and (c) those only found in Office II. When we compare all the Sankt Gallen witnesses to this office, as laid out Table 5, we can see that the Goslar Tonary has no chant from any of these categories. The Hartker Tonary, meanwhile, has the strange half-transmission of Office II to which I alluded above, as if this were new addition to the Sankt Gallen repertory. If that deduction holds, then it also follows that there would be no such traces in the Goslar Tonary.

Table 5 The antiphons of St Otmar as found (and not found) in tenth-century Sankt Gallen sources

Chants are separated into compositional layers and organised by tonary letter, with lacunae shaded.

But does this now mean that the Goslar fragment must be dated to a time before 920? Not necessarily. Although Walter Berschin seems never to have strayed from his belief that the earliest manuscript of the St Otmar office (Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. Guelf. 17.5 Aug. 4o) was copied during the time of Bishop Salomo III (890–920), perhaps even as early as 900, that dating has always raised more questions than it answers.Footnote 73 For starters, Berschin never reconciled his own palaeographical instincts with those of Hartmut Hoffmann, who placed the manuscript a full half-century later.Footnote 74 Then there is the fact that the original St Otmar office was composed with its antiphons in modal order. As Harmut Möller observed, this would be an ‘explosive discovery for musicology’ if the dating held up, for it challenges the orthodoxy that modal ordering techniques originated to the west with Stephen of Liège (d. 920).Footnote 75 Calendar evidence also casts doubt on such an early date, because although the accompanying Vita Otmari was a product of the ninth century, liturgical veneration of this saint at Sankt Gallen is not documented until later: Otmar first appears in the martyrology in Zurich, Zentralbibliothek, MS Car. C 176 (dated by its contents to 926×50), as well as in the two early Sankt Gallen tropers SG 484 and 381 (dated palaeographically to the same period).Footnote 76 Finally, there is the question of authorship. Ekkehart IV’s report that Notker II (d. 975) composed ‘delicate antiphons for Otmar’ has previously seemed impossible for Office I, yet nor does it fully square with the recycled quality of Office II.Footnote 77 However, were we to countenance a date closer to 950, we could bring Notker II back into the fold as composer of the original. Indeed, with Möller already having highlighted literary commonalities between Office I and Office II, it would be considerably easier to consider these as successive iterations of a single composer’s work.Footnote 78 All of this plays into my hands, I will gladly admit, but it also makes good sense of Hoffmann’s original conclusions. It was, after all, the palaeographer who placed the Wolfenbüttel manuscript in the second half of the tenth century who placed the Goslar fragment in the first.

hartker’s curation of the office

All of this wrangling has been for a greater cause, for if we can place the Goslar Tonary at Sankt Gallen in the first or second quarter of the tenth century, a number of historical implications follow. It is interesting to think about the fragment from a synchronic perspective, as a counterpart to the many innovative musical volumes from this fertile period at Sankt Gallen – among them the gradual portion of SG 342, the troper-sequentiaries SG 484 and 381, and the proto-processional in SG 18.Footnote 79 But the more important finding is arguably diachronic, since the Goslar Tonary testifies to a basic lack of change in the local Office chant repertory between the earlier tenth century and the making of the Hartker Antiphoner in the 990s. This is not so far from what Omlin deduced back in 1934, when he reasoned that the Hartker Tonary represented an older textual model overlaid with recent out-of-place additions.Footnote 80 But the finding takes on new meaning in the light of Rankin’s work on the wider Sankt Gallen situation, above all the gradual in SG 342, which was copied in the early tenth century and then corrected and updated at the turn of the millennium. In Rankin’s assessment, that book ‘illustrates a process of liturgical change, the development from a received Roman-Frankish liturgy to a St. Gallen “house version” during the tenth century’.Footnote 81 The two closely-allied tonaries thus encourage us to view the Hartker Antiphoner from that same perspective. In what follows, we shall examine the book’s possible accomplishments under three separate categories.

1. Reorganisation of Feasts

We have already seen how, mode for mode, the Hartker Antiphoner augmented the repertory contained in the Goslar and Hartker Tonaries. But comparison with the tonaries reveals that a handful of chants were also omitted. This might not be worthy of comment, were it not for the remarkably consistent categories into which the jettisonned chants fall. Among the patterns visible in Table 6, three chants were lost from the final week in Advent and no fewer than eleven from Thursdays in Lent.Footnote 82 Two points are worth bearing in mind. First, these numbers were undoubtedly higher, but our tonaries grant us access to little more than half of the Sankt Gallen Office repertory at large. Second, the agreement between the tonaries marks them out all the more as cut from the same cloth, thus pushing the responsibility for this apparent reform squarely at the feet of the Hartker Antiphoner. So what might have motivated such changes?

Table 6 Chants of the Goslar and Hartker Tonaries which are either omitted or differently assigned in the Hartker Antiphoner

Although each of the chants in Table 6 merits closer scrutiny, there are two categories of immediate value to our investigations here: the Lenten Thursdays and the liturgy of Septuagesima Sunday. The Lenten Thursdays are easiest to deal with, because the Hartker Antiphoner actually confirms what the table suggests: for the period from Ash Wednesday through to the fifth Sunday of Lent, chants were copied for every weekday except Thursdays. There was certainly nothing the matter with Lenten Thursday chants per se, because most of compositions ordinarily assigned to those days were also used for the Sundays after Pentecost, as they are in the Hartker Antiphoner.Footnote 83 Nor is there any reason to believe that the Thursday liturgy was itself abandoned. The Office would of course continue in its cycle with or without special chants, and we know from contemporary graduals that the Mass propers for these days also persisted. Only one option remains: this was a matter of liturgical coordination.

Thursdays in Lent are something of a cause célèbre in chant scholarship, thanks to their relatively late addition to the Roman stational calendar. The instigation of these Masses in the 720s famously necessitated the borrowing of existing proper chants from other feasts, a fact which has yielded vital clues for scholars about the formation of the Roman Mass proper.Footnote 84 But that story is a red herring here, for the solution to our problem lies not with the Mass chants, but with the Gospel lectionary on which these Office chants were based.Footnote 85 Back when the new Thursday Masses were inaugurated in the eighth century, the proper chants were of course not the only texts which needed to be established. New Gospels were also chosen, but for reasons unknown at least three competing sets emerged.Footnote 86 Two concern us here: a series of readings from Matthew and Luke, and a series from John. Both can be connected to capitulary traditions of the middle of the eighth century, the former series in books of Λ- and Σ-type, according to Klauser’s designation, and the latter in those of the Δ-type.Footnote 87 Although the precise distribution of these lectionaries in the Frankish lands is not fully understood, two facts are not in doubt. First, the core Romano-Frankish repertory of Gospel antiphons for Lenten Thursdays was based almost entirely upon the Matthew–Luke series.Footnote 88 Second, the Sankt Gallen lectionary tradition drew exclusively from the Johannine series.Footnote 89 Given this blatant liturgical impasse – illustrated in Table 7 as it applies to the second week of Lent – the problem was always going to come to the fore at some point.Footnote 90 What is interesting, from our perspective, is that this should have happened in the 990s in connection with the Hartker Antiphoner. There is no space here to elaborate on the underlying intellectual or political contexts, but we can very quickly make a point about the relative status of liturgical authorities: it was the Gospel lectionary, not the authorised antiphoner, which proved decisive in this particular instance of musical change.

Table 7 Gospel chants in the Hartker Antiphoner compared with Gospel lectionaries for the second week in Lent

Italicised chants are found in Sankt Gallen tonaries, but were omitted in the Hartker Antiphoner.

That observation brings us to a second instance of abandonment in the Hartker Antiphoner, the responsory Alleluia mane apud nos for Septuagesima Sunday. Although this particular omission was not known to him, Froger knew instinctively that there was something not quite right about Septuagesima as we find it in the antiphoner.Footnote 91 The page in question (SG 391, p. 134) has a distinct and uncharacteristic change of scribal hand, which coincides with a squashed rubric and an abbreviated repertory of chants. There is no proper material here for Matins, but instead a cursory direction to sing the responsory Si oblitus ‘cum reliqua’, which in translation means that the music is to be borrowed from the fifth Sunday after Easter. This is not what we would expect for this threshold-crossing Sunday of the Temporal cycle, which marked the end of Epiphany and the beginning of the pre-Lent season. With good reason, Froger thought there had been a problem with an exemplar. What the Goslar Tonary indicates, however, is that the solution may lie in precisely what had not been copied.

The Hartker Antiphoner is unique among the earliest surviving Office antiphoners in that it does not transmit a special set of Septuagesima chants for the so-called Farewell to the Alleluia, a ceremony which marked the departure of the Alleluia for the penitential season of Lent.Footnote 92 At some point in its long and distinguished history, this occasion acquired an irreverent historia full of humerous misappropriations of Scripture.Footnote 93 The responsory Alleluia mane apud nos (‘Alleluia, stay with us’) is a classic example, based on a passage of very different intent in Judges 19:9. Concordances in Old Hispanic sources, as well as a lack of concordance with Old Roman ones, suggests that the Alleluia office was a Spanish creation which entered Romano-Frankish practice via Gaul.Footnote 94 We cannot know if these imports replaced an older Roman set of chants for Septuagesima, but we do know that the office was in conflict with the Office lectionary, which directed the book of Genesis to be begun at Septuagesima Matins.Footnote 95 There survives a Romano-Frankish repertory of Genesis responsories, and logic dictates that these were composed to be sung in dialogue with the readings, as is standard practice for the rest of the church year. But in our earliest Frankish antiphoners the Genesis chants are routinely delayed until the following week.Footnote 96 Given that the Hartker Antiphoner still has the displaced Genesis responsories, it has always seemed likely that Sankt Gallen had once known the Alleluia office at Septuagesima, only then to abandon it. The combination of the Goslar Tonary’s testimony and a suspicious Seputagesima lacuna in the Hartker Antiphoner now more or less proves that they had.

So why abandon the Alleluia office at Sankt Gallen? It was certainly not because of the underlying concept of a Farewell. This demonstrably continued, not only through the suggested substitution of Paschal office Si oblitus fuero, which is full of chants which playfully sing the praises of the Alleluia, but also in other genres known at Sankt Gallen, for instance the delightful hymn Alleluia dulce carmen (‘Alleluia, song of gladness’).Footnote 97 Rather, the abandonment of a chant like Alleluia mane apud nos must be explained by a change of attitude. If the example of the Lenten Thursdays is anything to go by, the problem was once again the scriptural dissonance created by the chants. Indeed, towards the end of his life Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048) penned a lengthy liturgical commentary in which he criticised two related tendencies in the Septuagesima liturgy: the rejection of the Alleluia office as scripturally appropriate and the use of the Si oblitus fuero office in its place.Footnote 98 Since no other institution is known to have sung Si oblitus fuero in this way, and since there is no example of this practice at Sankt Gallen prior to the Hartker Antiphoner, it is difficult to interpret Bern’s words as anything other than a critique of his neighbours’ recent reform.

Thus the reorganisation of both the Lenten Thursdays and Septuagesima Sunday reveal something quite unexpected about chant practices in late tenth-century Sankt Gallen. Elements of the repertory were being consciously reworked. The evidence considered above could be construed in terms of project to re-Romanise the liturgy in the image of Pope Gregory, bringing authoritative liturgical texts back into an imagined former state of alignment. But the reality was surely closer to the opposite. By the very act of engaging with the content of their chant repertory, that which Ekkehart IV would later attribute to Rome, the scribes were forcing received practices into line with contemporary needs and opinions, precisely as Rankin hypothesised in relation to the gradual SG 342. In that sense they were actually making their music less ‘Roman’ than ever.

2. Benedictinisation, or not

A similar dynamic must have been in play whenever it was that the Sankt Gallen monks first decided to ‘Benedictinise’ their Office liturgy. In simple terms, this process entailed expanding the festal form of Matins from a secular cursus (with nine Psalms, nine antiphons, nine lessons and nine responsories) as inherited from Roman practice, to a more properly monastic one (with twelve of each) as prescribed in the Benedictine Rule.Footnote 99 The impulse for this reform came from the Council of Aachen in 816, but its adoption in European monasteries was in fact both slow and uneven, even in those places which were outwardly disciplined followers of the Rule.Footnote 100 Sankt Gallen is a prime case in point. In his brief exposé of liturgical books for the Office from the generation after the Hartker Antiphoner, Pierre-Marie Gy demonstrated the variable, even experimental, state of these books, as late as two centuries after the Aachen decree.Footnote 101 And the point has often been made that the Hartker Antiphoner itself looks like a liturgical reform in progress. As Hesbert showed systematically a few years after Gy, the book is a strange hybrid, with Benedictine groupings of antiphons freely coexisting beside Roman groupings of responsories, alongside a multitude of chants which strictly correspond to neither category.Footnote 102 An instinctive reading of this situation is that Hartker and his fellow scribes were midway through an attempt to bring the Office liturgy into line with Benedictine practice. But instinct is no longer required: the two Sankt Gallen tonaries now give us both the incentive and the means to test that thesis once and for all.

The basic case in favour of Benedictinisation in the Hartker Antiphoner runs as follows. Rather than being clumped together, the book’s seventy or so ‘added’ chants (i.e., those which should concord with the earlier Sankt Gallen tonaries but do not) are spread consistently and evenly across all the Church Year, with no one occasion unduly favoured.Footnote 103 Although we only have a partial set of data, the addition of one or two antiphons per liturgical occasion is at least statistically plausible for the kind of expansion which the Benedictine Rule required. (A monastic Matins has four extra antiphons, but a monastic Vespers has one less.) Thus when we find two antiphons apparently added to Matins on the feast of All Saints, Beati quos elegisti (CAO 1594) and Benedicite domino (CAO 1699), both assigned to the third and final nocturn, it seems reasonable to assume that there was also a third addition, now hidden by a lacuna, which brought the total number of antiphons from the Roman nine to the Benedictine twelve. The responsory repertory can also be rationalised in this way. For the feast of the Holy Innocents there are two third-mode responsories in the Hartker Antiphoner which are not present in the Goslar Tonary, Effuderunt sanguinem (CAO 6624) and Coronauit eos (CAO 6342), whose presence in the antiphoner leaves us with the strangely anomalous total of eleven Matins Responsories. Without them, however, we have the standard Roman nine. Similarly, Diligebat autem (CAO 6454) for John the Evangelist brings the Hartker total to ten, as does Audistis enim (CAO 6147) for St Paul. The implication is that we are seeing these feasts en route to the requisite twelve responsories prescribed in the Benedictine Rule.

Unfortunately, these kinds of argument do not hold up to scrutiny. Most of the hypothetically ‘added’ chants turn out to be core members of the Romano-Frankish repertory, whose late addition to the repertory at Sankt Gallen would be a matter of genuine surprise.Footnote 104 To put it differently, the absence of these chants from the Sankt Gallen tonaries can be explained more convincingly in other ways, for instance by the alteration of a modal assignment or by an anomaly of liturgical ordering. The case for Benedictinisation unravels further when we learn that the service of Matins, which would be the expected site of monastic augmentation, is not at all the focus of the seventy chants supposedly ‘added’ to the Hartker Antiphoner. Nor do these chants cluster around the most fully Benedictine of the antiphoner’s major offices, above all Christmas, Epiphany, and Assumption. (All Saints is the one exception.) Rather, it is the Lauds and Vespers antiphons which predominate among ‘additions’, along with alternate or unassigned chants which were presumably for use during the other, lesser Office hours. This is not plausibly the consequence of adapting the Office liturgy to the Benedictine cursus, and it suggests that other forces were at work.

Indeed, I would go so far as to say that the tonaries yield positive evidence against the active Benedictine adaptation of the Office liturgy in later tenth-century Sankt Gallen. But that does not mean that the monastic cursus was unknown. For starters, the tonaries communicate most if not all of the chants which in the Hartker Antiphoner are assigned as Matins canticle antiphons, a category of chant which was exclusive to the Benedictine cursus. Then there is the strongly Benedictine testimony of the community’s more recent musical additions. The office of St Gall, dated by Berschin to the years around 900, was crafted from the beginning according to the newer cursus, and the same can be said of the second version of the St Otmar office (the first version is non-specific) as well as the St Afra office.Footnote 105 What this accumulated evidence would seem to suggest, then, is that the mixed Benedictine and Roman aspects of cursus in the Hartker Antiphoner – aspects which scholars have been inclined to interpret as temporary aberrations – had in fact long co-existed at Sankt Gallen. How this worked in practice is by no means clear, nor is it easy to explain why the monastery would have been comfortable with this outwardly indisciplined state of affairs. But from the perspective of the Hartker Antiphoner, a large distraction has been removed from view. To the extent that these Sankt Gallen scribes were actively shaping and curating their Office chant repertory, which they most surely were, I suggest that their intentions lay elsewhere.

3. Hartker the Collector

The idea that the Hartker Antiphoner ‘added’ to the Office repertory at Sankt Gallen probably needs to be understood in a more simplistic sense. We are not dealing with the redesign of the cursus, I would contend, but simply with a musical repertory which had been expanded. The enlarged quality of the antiphoner has been noted by many scholars before, among them Ruth Steiner, who wrote of Hartker the ‘collector’, the monk who acted as the ‘preserver of traditions of worship that extend far beyond those of his own community’.Footnote 106 This interpretation does not exclude the possibility that Sankt Gallen scribes were working towards a fully Benedictine liturgy, or at least the possibility thereof. But in execution we may be witnessing something much closer to the work of early tenth-century monks at Sankt Gallen, above all those responsible for the troper-sequentiaries SG 484 and 381 and the processional SG 18, in whose books the basic scribal procedure seems to have been one of bringing materials together first and worrying about their destiny later.Footnote 107 With the benefit of tonary evidence, we can now see this process in the work of Hartker.

As already mentioned, the ‘added’ chants in the Hartker Antiphoner seem not to have been prioritised for use at Matins, nor do they seem to have favoured major feasts. (Note that the term ‘addition’ as used here refers not to a specific scribal act, but simply to a perceptible augmentation of the repertory.) Instead, the early Sankt Gallen tonaries indicate that in the Hartker Antiphoner the newer chants characteristically occupied a place near the end of a given occasion. Such chants can be interpreted as alternatives for Lauds or Second Vespers, or as canticle antiphons for the weekdays of an octave. But the lack of rubrication may equally suggest a lack of defined liturgical place, not unlike the new saints’ offices which Omlin found to contravene the ordering of the Hartker Tonary. Many of these ‘additional’ chants are also more narrowly transmitted, as local or otherwise extraneous members of the Office repertory. An example is the antiphon Haec locutus sum (CAO 3009), an absentee from the tonaries which was included in the Hartker Antiphoner as the ninth of nine supplementary chants for Pentecost (SG 391, p. 78). Not documented in any other CAO source, it appears to have a distinctively Aquitanian (and thus non-Roman) line of transmission, quite unlike the chants with which it shares its page.Footnote 108

Potentially the most extreme example of a collecting behaviour is the block of twenty extra antiphons which were copied after Second Vespers for the feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross (SG 391, pp. 63–5). With a distinctive textual quality which sets them apart from other Holy Cross chants, as already noted by Lori Kruckenberg, and with a concordant source which places them under the rubric ‘ad salutandam crucem’ (for the salutation of the cross), it appears that these chants had not been copied with specific attention to the Divine Office.Footnote 109 Rather, as Table 8 implies, this was a supplementary repertory which may have been assembled cumulatively over several decades. By that logic the most recent addition was Sanctifica nos domine, a chant which happens to have been intimately bound up in the eleventh-century monastery’s sense of self. As told in the local history of Ekkehart IV, written a generation after Hartker, Sanctifica nos domine was the song sung by the brave monk Heribald in the face of early tenth-century Hungarian invaders.Footnote 110 In her analysis of Ekkehart’s story, Kruckenberg noted the supreme narrative value of this chant above all others, drawing attention to its pointed text and emphatic closing flourish.Footnote 111 But if the tonary evidence is to be believed there may be another angle on Ekkehart’s choice. As one of the most recent additions to the Holy Cross repertory at Sankt Gallen, and by all accounts a relatively recent composition in its own right, Sanctifica nos domine would have stood among the compositions which most profoundly projected a sense of local, native identity in the face of an external threat. At any rate, we are clearly not dealing with something from the core Romano-Frankish repertory, but with an addition thereto.

Table 8 Supplementary chants for the Invention of the Holy Cross as found in the Hartker Antiphoner, with tonary concordances

Lacunae are shaded.

It is a similar story for the Hartker Antiphoner’s eight supplementary antiphons at the end of the feast of the Assumption (SG 391, p. 106). The latter half are either missing from the Hartker and Goslar Tonaries or lost in their lacunas, while the second chant is additionally absent from the Goslar Tonary. It is the sixth supplementary antiphon which should interest us most, though, because it is textually identical to the first. In the Hartker Antiphoner both chants bear the words Maria virgo semper (CAO 3708), but the second has been notated with a different melody. No other contemporary antiphoner brings together two melodies for this chant, and I am aware of this juxtaposition only in the Hartker Antiphoner and in later sources which directly depend upon it. Wider concordances help us to distinguish the one from the other. Whereas the first version is a seventh-mode melody and is also found in the Old Roman tradition, the second is a first-mode composition with a narrow transmission among Germanic sources, and is unknown prior to the Hartker Antiphoner.Footnote 112 (A comparison is presented in Figure 4.) Once again, it appears that items of local interest were supplementing a received repertory of much older pedigree.

Figure 4 Two versions of Maria virgo semper from the Hartker Antiphoner, together with later pitched readings from Einsiedeln and the Old Roman tradition

Some of this collecting activity may also have taken place in the library. The Hartker Antiphoner is the earliest known source to contain a group of four supplementary ‘O’ antiphons, sometimes known as the ‘monastic O’s, found appended to the normal group of eight (SG 390, p. 41).Footnote 113 A single correspondence with Alcuin’s De laude dei, written in late eighth-century York, suggests that the group of four were themselves ancient compositions.Footnote 114 But a continuity of practice at Sankt Gallen cannot be assumed, on the basis that the aforementioned late ninth-century endleaves of SG 86, of possible Sankt Gallen origin, contain no more than the standard eight ‘O’ antiphons (pp. 231–2). The possibility is thus raised that the four had been newly reinstated. In another possible instance of appropriation, three apparently ‘added’ chants for the Common of a confessor, namely Homo iste, O quam venerandus and Suffragante domine (SG 391, p. 187), find a common concordance in the early tenth-century processional SG 18 (pp. 23 and 31). Along similar lines, the scores of versus (versicles) and responsoriola (short responsories) which are such a distinctive feature of the Hartker Antiphoner – and which led Aimé-Georges Martimort to believe that this was the earliest chant book to bear witness to the versicle genre as a wholeFootnote 115 – actually find earlier concordances in none other than SG 86.Footnote 116 Examples include Emitte agnum on p. 1 (CAO 6655), only otherwise found in the CAO source from Rheinau (Zurich, Zentralbibliothek, MS Rh. 28), and Omnes gentes quascumque on p. 4 (CAO 7315), only otherwise found in the CAO source from Bamberg (Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Lit. 23). These are but crumbs of evidence, but they do point towards a common conclusion. Although Ruth Steiner painted a memorable picture of Hartker the foraging scribe, preserving traditions ‘beyond those of his own community’, that description probably needs to be turned on its head.Footnote 117 The examples presented above suggest that it was actually a fundamentally external tradition, that which we might call Roman or Romano-Frankish, which in the Hartker Antiphoner was being personalised with materials from closer to home.

conclusion

The collective testimony of the Sankt Gallen tonaries therefore leads us to the very conclusion which I primed us to expect: in the Hartker Antiphoner an older Roman inheritance was being expanded with material of a more local nature, including new offices for saints’ feasts, new texts, new alternative chants, and even one or two new chant melodies. These observations find direct points of contact not only in the turn-of-millennium adaptations made to the gradual SG 339, but also in contemporary materials from further afield. For example, a clear parallel for the doubly notated Maria virgo semper chant is the doubly notated Monasterium istud of the slightly earlier Swiss gradual Einsiedeln, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 121.Footnote 118 A more general comparandum comes in the form of Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat. 1085, the St Martial Office antiphoner whose archaisms and possible relics of Gallican practice were interpreted by James Grier as ‘a systematic attempt to record the texts of the Divine office’.Footnote 119 The idea of including ‘everything’ is also mirrored in contemporary compilations of other genres, perhaps most notably the eccentric liturgical assemblage known as the Pontifical Romano-Germanique, coterminous with Hartker, among whose diverse musical materials are several processional chants composed in Sankt Gallen.Footnote 120

At the same time as the Hartker Antiphoner was recording a newly expanded repertory, however, the scribes were also working in an editorial capacity. From our two case studies of omitted chants, for Lenten Thursdays and Septuagesima, it appears that scriptural harmony was a primary consideration in the curation of the repertory. But other factors may have played a part. Whatever the ultimate motivation was, it is instructive to note that the reform of the Lenten Thursdays at Sankt Gallen did not completely stick. Some of the omitted chants were reinserted into the margins of the early eleventh-century breviary SG 414 (e.g. pp. 500, 504), and were then included again in full in the breviary SG 413, from the 1020s or 1030s, only for the reforms to be reinstated again in the twelfth-century breviary SG 388. One likely explanation for this prolonged inconsistency is that the monks did not have the musical resources to achieve their higher liturgical aims. (They certainly never adopted chants based on the Johannine Gospel lectionary, as other institutions did.) The interpretation is attractive because it is also applicable to the Hartker Antiphoner’s hybrid liturgical cursus. We know from examples above that the Sankt Gallen community was at least partially committed to the Benedictine way of performing of the Office. But we have also seen via the tonaries that there had been no major advances on this front since the first half of the tenth century. In these various senses, then, the Hartker Antiphoner must indeed be considered part of a longer work in progress.

All of this draws us back to a central question: why should the Sankt Gallen community have placed such emphasis on the musical authority of the Hartker Antiphoner, both in its famous Gregorian image and poem, and indirectly in the narratives of Ekkehart IV which followed a decade or two later? Or to put it another way: why make such a big deal of Romanness in a repertory which, as the tonaries imply, had never been less Roman?Footnote 121 In the context of a chant book which had plenty of other illustrations besides, there is certainly a danger that we over-obsess about the significance of this single famous opening. But I think the questions comfortably furnish their own answer. Knowing that their repertory was in fact less Roman than ever – not only in its incorporation of new chants, but also in its subjugation to the higher authorities of the Bible and Gospel lectionaries – the scribes may have been pushing hard in the opposite direction, overcompensating for a perceived lack of absolute musical authority. Perhaps they were even aware of the kinds of critique which Bern of Reichenau would later direct their way. Of course we can do no more than speculate about the motivations of the Hartker Antiphoner’s late tenth-century scribes. In the case of Ekkehart IV, however, the liturgical evidence uncovered in this article opens up a new dimension in his work.

Scholars of this significant eleventh-century historian and thinker have long recognised that he had something to prove. Ekkehart was certainly interested in presenting his institution as musically gifted, as well he might.Footnote 122 But the liturgy was also at the forefront of his agenda. As Kruckenberg has argued, one of the ‘central aims’ of his institutional history, the Casus sancti Galli, ‘was to provide proof that, over the centuries and up to his day, the monks of Sankt Gallen lived in accordance with the Rule of Benedict’.Footnote 123 Now that we know of a specific liturgical context in which the Sankt Gallen monks’ non-compliance with the Rule might have been daily exposed, the Hartker Antiphoner’s projections of antiquity and Ekkehart’s protestations of obedience both take on a radically different hue. This is all the more interesting when we consider that the earliest evidence of a consistently Benedictine cursus at Sankt Gallen appears in SG 413, a breviary volume copied in the second quarter of the eleventh century, just at the point that Ekkehart IV was emerging as a major local voice.Footnote 124 Evidence of a cursus reform in this period would, in turn, strengthen the idea that the hybrid liturgy of the Hartker Antiphoner had been a longer-term fixture at Sankt Gallen. But even if the liturgical creases had been ironed out by Ekkehart’s time, he knew the library too well to be ignorant of this less-than-Benedictine past.

Thus, in a strange way, this article brings us to a state of knowledge which both affirms and undermines the Hartker Antiphoner’s legendary historiographical status, the problematic matter with which we began. The relative stability of the tenth-century Goslar and Hartker Tonaries, combined with only limited evidence of intervention by Hartker and his fellow scribes, should renew our confidence that this book did indeed preserve something of an older repertory. Perhaps we might even attribute the antiphoner’s hybrid cursus to a time earlier in the ninth century, when Benedictine adherence had last been high on the Frankish agenda. But that does not make this book any more Roman, of course, and the existence of cumulative Frankish reworking is plain to see from the various early witnesses to the Sankt Gallen Office which survive. The tonaries have now revealed that this reworking continued in the Hartker Antiphoner, demonstrating that this was no passive copying exercise, but an active project in which the authors exerted their editorial control, reorganising, excluding and adding new materials. What was also new in this book, so far as we can tell, was the effort expended on authorising its contents. In a time of rapid musical and liturgical change, stability was presumably exactly what they wanted us to hear – and we as scholars have been only too glad to hear it. But with tools like the Goslar Tonary we can look behind the curtain and see for ourselves.

Plate 1 Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1, fol. 1r

Plate 2 Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1, fol. 1v

Plate 3 Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1, fol. 2r

Plate 4 Stadtarchiv Goslar, Handschriftenfragmente MThMu 1/1, fol. 2v

1 Omnes enim vos appears in later Sankt Gallen books as a post-Pentecost chant in mode 4 (og or oh), so the reason for its placement here is unclear.

2 Normally assigned to mode 7 (yg), Beatus vir qui timet is out of place both melodically and liturgically. It is probably a mistaken substitution for Beatus uir qui inuentus (CAO 1675), which in the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner is assigned to mode 3 (ic) and saints’ feasts in Eastertide.

3 No office chant of this name is known, only a canticle. Given the similarity to the previous entry, its inclusion may have been accidental.

4 Normally assigned to mode 5, Ego sum vitis vera is out of place both melodically and liturgically. It is probably a mistaken substitution for Ego sicut vitis fructificavi (CAO 6633), which in the Hartker Antiphoner is assigned to mode 3 and Easter 3.

5 Normally assigned to mode 3 (ye), Angeli archangeli throni is out of place both melodically and liturgically. It is probably a mistaken substitution for Angelus archangelus (CAO 1406), also for St Michael, which in the Hartker Antiphoner is assigned to mode 3 (yc).

6 The more common reading is ‘potentiam’.

7 Although sometimes found written ‘Cibavit illum’, the reading ‘Cibavit eum’ is native to German sources of this period, including the Hartker Antiphoner.

8 Since there is no other ‘Responsum accepit’ chant, this must be an accidental duplication.

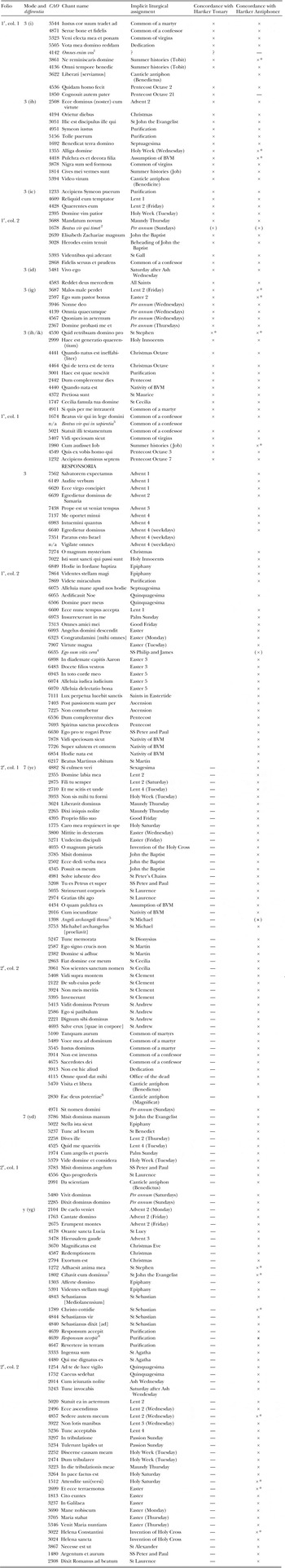

APPENDIX

The Contents of the Goslar Tonary

The chant incipits of the Goslar Tonary have been transcribed faithfully below, subject to the standardisation of spelling and capitalisation of proper names. Angled brackets denote words or syllables omitted by the scribe; square brackets denote extra words supplied in order to clarify the identity of a chant. Italics denote anomalous or problematic chants.

Concordances are noted only when found in the original scribal layers of the Hartker Tonary and Antiphoner. An em rule indicates that there is a lacuna where we might expect to find evidence. An asterisk denotes a concordance found in a different melodic classification. Parentheses in the concordance columns assume a copying error (discussed in a footnote) and indicate that the concordance pertains to a suggested alternative.