Historians of science have typically used one of three ideal-types to identify individuals who pursued knowledge about nature in 19th-Century Britain. The first is the ‘gentleman of science’, for whom science was a vocation, and whose reputation was staked upon their financially disinterested pursuit of knowledge; from mid-century, there emerged ‘men of science’ who practised science as a paid career; and finally, there were collectors, writers, and correspondents, including many women and working-class individuals, whose contributions to the production of knowledge have gradually been recovered by historians since the second half of the 20th Century.Footnote 1 All of these groups recognised the importance of scientific societies and associations to the production of scientific knowledge. As Ruth Barton has argued, ‘participation in gentlemanly networks and alliances with gentlemanly amateurs were means by which the new professionals exercised cultural leadership’.Footnote 2 Women were able to attend meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) and, when expedient, they were allowed to join associations such as the Botanical Society of London (f. 1836) and the field naturalists' societies that flourished in the second half of the century.Footnote 3 Meanwhile, for working-class practitioners, meeting in clubs, such as mutual improvement societies, and in public houses was a means of distributing the costs of buying books and sharing knowledge about nature.Footnote 4

James Croll was conspicuous by his absence from scientific ‘clubland’.Footnote 5 Croll accepted fellowships and honorary memberships of eight societies (Appendix 1), including the most prestigious award of all, Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1876, but almost never appeared at any scientific meetings. As a predominantly self-educated man, who worked variously as a millwright, insurance agent, newspaper clerk, tea-shop keeper, and museum janitor, Croll may be assumed to have lacked the requisite connections to navigate his way into social networks in science. However, an examination of Croll's correspondence reveals Croll's strategic navigation of clubs and associations according to his own, very different vision of science, unfettered by party or sect.

Despite being one of Scotland's leading philosophical physico-geologists, Croll did not engage with the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE). In this article, I will investigate the reasons behind Croll's choices. This is best done by comparing the RSE with the scientific associations Croll most favoured. I shall, therefore, situate the RSE, the Geological Survey, where Croll was employed as resident surveyor and office clerk, and Croll's preferred journal, the Philosophical Magazine, in their respective social and cultural contexts, arguing that the more socially inclusive context offered by the Survey and Magazine proved more conducive to Croll's vision of science: a collaborative enterprise, united across emergent disciplines, and unaffiliated with party or sect. I conclude by suggesting how analyses of Croll and figures like him offer to nuance prevailing understandings of models of authority in mid- to late-19th-Century science.

1. Contexts of conviction: Croll's vision of science

By the later 19th Century, the disinterested pursuit of knowledge, primarily the privilege of gentlemen of independent means, was no longer the only path to establishing trust and authority in science. There were increasing numbers of professional men of science, who tended to share standardised educational experiences, institutionalised disciplines, and laboratory training. They differed from men from humble backgrounds, such as Michael Faraday, the son of a blacksmith, and later John Tyndall, born to a shoemaker who then joined the Irish constabulary, who had forged careers as scientists, and were paid for it.Footnote 6 The new professionals were gentlemen such as Joseph Dalton Hooker, who stressed their philosophical approach to science.Footnote 7

Historians have paid close attention to the self-presentation of those working-class men who rose to prominence in science. It is argued that their acceptance by a professionalising scientific community was facilitated by their conformity to a set of standard practices. In this way, Alice Jenkins analysed Faraday's ‘artisan essay circle’, finding Faraday's attempts to improve his literary style a part of his larger project to develop the skills needed to support and promote his scientific work. Jenkins argues that Faraday sought to eliminate evidence of his low social status when communicating his research in publications, correspondence, and lectures, in order to become a man of science.Footnote 8 Consolidating these skills and forming strategic allegiances with fellow men of science, institutionalised in the form of scientific societies, has been seen as key to the emergence of a professional sphere.

Croll's trajectory, from similarly humble beginnings, did not follow the same path as Faraday's to professorships and memberships of select societies in Britain's scientific establishment. This was not purely the result of snobbishness on the part of rising professional men. In 1874, the Rev. Cunningham Geikie asked Croll, then living in Edinburgh, ‘Why don't you come to the front now? A man with your brain & power of expression might do pretty much what he liked in making a name for himself in scientific matters, and in serving his day’.Footnote 9 Yet, in what had by then become a typical response, Croll demurred. This cannot be attributed to Croll's illness in 1873 (although that had resulted in a notable gap in his otherwise extensive publication record of between five and seven scientific articles per year) because even in periods of good health, he refused most invitations to attend scientific meetings in person.Footnote 10

In 1870, Croll refused an invitation from the Royal Institution ‘to give a short course of three lectures on any geological question, or on ocean currents, or on any other subject’.Footnote 11 Having to travel to London may have put Croll off, but the following year, he also declined an invitation to attend the BAAS meeting when it was to be held in Edinburgh. Writing to Professor George Carey Foster at University College, London, Croll explained that he had been off duty from the Geological Survey due to ill health for two months and ‘could not’, therefore, ‘with a clear conscience, ask for a leave of absence to attend’.Footnote 12 However, in 1872, Croll was again invited to speak at the BAAS meeting, this time in the Geographical Section. Specifically, Croll was asked to deliver a talk on his views on oceanic circulation and currents with William Carpenter, then President of the BAAS, and against whom Croll had been engaged in a protracted debate in the Philosophical Magazine for two years.Footnote 13 Once again, Croll declined. Finally, in 1876, the BAAS meeting was due to be held in Glasgow and Croll was invited to present. Characteristically, Croll submitted a paper but declined the offer to attend in person.Footnote 14

There were many reasons why Croll may have sought to avoid attendance at the BAAS, among which may have been fear of experiencing condescending treatment on account of his low social status. Just one generation earlier, naturalist Charles Peach read papers on fossils at the 1844 meeting in York. Peach's attendance was described in Chamber's Edinburgh Journal: ‘But who is that little intelligent-looking man in a faded naval uniform, who is so invariably seen in a particular central seat of this section?’Footnote 15 Peach was considered ‘one of the most interesting men who attend the Association,’ chiefly because:

he is only a private in the mounted guard … at an obscure part of the Cornish coast, with four shillings a day … most of whose education he has himself to conduct. He never tastes the luxuries which are so common in the middle ranks of life, and even amongst a large portion of the working classes.Footnote 16

The article concluded, ‘thou art an honour to human nature itself; for where is the heroism like that of virtuous, intelligent, independent poverty? and such heroism is thine!’Footnote 17 It would be easy to suppose that Croll was highly conscious of his low rank, regional accent, and ‘nervous disposition’, which would detract attention from his scientific work and direct focus instead to his social background.Footnote 18 This is what happened when Samuel Smiles published a biography of Thomas Edward, the shoemaker-naturalist, who was instructed to avoid public appearances in order to preserve the reputation Smiles had created for him in print.Footnote 19 Croll demonstrated a perceptive disdain for the genre of working-class biography and was extremely reluctant to collaborate in any kind of autobiographical or biographical work. One generation after Peach's appearance at the BAAS, however, Croll was working on the Geological Survey of Scotland alongside Peach's son, Benjamin, who had attained the rank of Geologist just one year before Croll, in 1868.Footnote 20 Benjamin Peach was largely able to avoid the class-based judgements experienced by his father after Roderick Murchison noticed Benjamin's abilities and arranged for him to attend the Royal School of Mines, where he studied under Thomas Henry Huxley and Andrew Crombie Ramsay.Footnote 21

Croll resisted being cast into the ideal type of a working-class practitioner both in print and in his early correspondence. As early as 1849, Croll had told his friend, mentor, and lifelong correspondent, the Rev. James Morison, ‘You express at the end of your note a wish to know something concerning me. This I am happy to do, though I am sure that, when you know it, it will be of little service to you’.Footnote 22 In this way, Croll resisted identification with working-class men who began correspondence with scientific men of higher social rank by offering biographical information, their candour about their poverty a means of conveying their trustworthiness.Footnote 23 Presenting himself as worthy of reply on account of his intellectual merit alone, Croll began a practice he pursued throughout his life.

Through his resistance to being cast in the same mould as a working-class autodidact, Croll also demonstrated a desire shared by many scientific men of the period to efface ‘the self’ from science.Footnote 24 In a letter to Croll in 1871, the clergyman and geologist Rev. Osmond Fisher confessed himself ‘much pleased to find that you think much as I do about the self-assertion now so much in fashion in the scientific world’.Footnote 25 By beginning each new epistolary relationship with an introduction to his theories as opposed to biographical information, Croll ‘wrote in order to have no face’.Footnote 26 In this way, William Clark described Thomas Henry Huxley, who ‘considered personal autobiography irrelevant, even self-indulgent’, ultimately writing only nine pages under protest.Footnote 27 Likewise, an incomplete draft of Croll's 33-page ‘autobiographical sketch’ was written only at the tireless insistence of Croll's future biographer James Campbell Irons and due to the patience of Croll's wife Isabella, who acted as Croll's amanuensis.Footnote 28 Avoiding in-person meetings and confining his scientific engagements to publications and correspondence, Croll nevertheless cultivated a ‘professorial persona’, an ‘essential feature’ of which was a voice that combined charisma and traditional authority, ‘which coexist with and condition’ objectivity in science.Footnote 29

While they shared a desire to pursue knowledge objectively, Croll and the emerging men of science had very different ideas about what constituted ‘traditional authority’. Croll's own convictions are revealed through his correspondence with the Rev. Morison. On the topic of his invitation to attend the BAAS meeting in Glasgow in 1875, Croll wrote:

I shall have a paper in Section A. but will not manage to be present. … I have not been at a scientific meeting for upwards of half a dozen of years. The real truth is, there is a cold materialistic atmosphere around scientific men in general, that I don't like. I mix but little with them.Footnote 30

‘Materialism’ was a ‘slippery signifier’ in this period, typically marshalled to attack the character of a scientific practitioner and the wider, deleterious social consequences of the type of scientific work they pursued.Footnote 31 In the minds of 19th-Century auditors and readers, the term had long been associated with the godless, revolutionary philosophy that had underwritten France's violent revolution at the end of the 19th Century.Footnote 32 Accusations of ‘materialism’ became particularly polarising after John Tyndall's infamous address at the Belfast BAAS meeting in 1874, in which Tyndall ‘discern[ed] in … Matter … the promise and potency of all terrestrial Life’.Footnote 33 As Darwinian men of science grappled with the perceived implications of their convictions, a large proportion of their time and energy was spent dissociating themselves from this highly charged epithet in print.Footnote 34

To the Rev. Fisher, Croll confessed that there were ‘several reasons’ for his absence from BAAS meetings. The ‘chief reason’, Croll admitted, was ‘that I dislike all such public displays’. But ‘the truth’, Croll confessed, was that he had ‘very little sympathy with the leading idea of the British Association, viz., that science is the all-important thing’. ‘You can hardly expect’, Croll continued, ‘one who has devoted twenty years of the best part of his life to the study of mental, moral, and metaphysical philosophy to have much sympathy with the narrow-mindedness of the British Association’.Footnote 35

Croll shared his optimism with Fisher and Morison that ‘there is, however, indication of a reaction beginning to take place towards something more spiritual in science’, and, adapting a phrase from Thomas Dick's Christian Philosopher, a work that had inspired Croll in his early course of self-education, Croll concluded, ‘the day, it is to be hoped, is not far distant when religion, philosophy, and science will go hand in hand’.Footnote 36 In contrast to his distaste for meetings with ‘materialistic’ men of science, Croll declared that he would be ‘delighted to come through to Glasgow and spend an afternoon’ with Morison.Footnote 37 For Croll, the pursuit of knowledge was the pursuit of a spiritual truth, unfettered by worldly nepotism or political affiliation. It was with this attitude that Croll navigated the landscape of scientific associationalism.

2. Edinburgh societies

In his study of Charles Lyell's navigation of London institutions, J. B. Morrell began, ‘it is too easy to assume, with naïve optimism, that if [scientific societies] existed they must have been functionally effective for scientists. This was not necessarily so.’Footnote 38 While many societies played a crucial role in the emergence of a professional culture of science in the nineteenth century, Morrell's description held true for a number of other associations which claimed to be engaged in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. In his seminal study of the founding of the RSE in the 18th Century, Steven Shapin revealed that the ‘inherent requirements of intellectual scientific activity were a negligible factor in the establishment of a major scientific organisation’.Footnote 39 As practitioners, including Fellows of the Society, perceived the pursuit of knowledge about nature as ‘a constituent of general literate culture’, it followed that ‘the institutions in which men of science functioned, whether university, academy, or scientific society, were subject to many of the same social, political, and cultural forces as the institutions that sustained the practitioners of belles-lettres, medicine, antiquarian studies, or law’.Footnote 40 Deeply and inextricably embedded in Edinburgh's cultural landscape, a study of the RSE is at once ‘a study of the local politics of culture’.Footnote 41

Founded in 1783 by distinguished practitioners like William Cullen, John Hope, and John Pringle, already by the end of the 18th Century, the RSE was regarded as the second most important scientific society in Britain.Footnote 42 The Society's membership base was unaffected by the demographic disruptions experienced in Britain's industrialising cities. As Britain's middle classes sought to transform their newfound economic capital into cultural self-expression, medical men, dissenters, and factory owners came together to form clubs, most notably ‘Literary and Philosophical Societies’.Footnote 43 The period became renowned as a ‘golden age’ for ‘membership-based organisations’ and the phenomenon of ‘associationalism’ flourished in the rapidly urbanising towns and cities of Glasgow, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Manchester.Footnote 44

While Britain's industrial cities grappled with the polarising social and economic impacts of industrialisation, Edinburgh's economy remained predominantly culture- and service-based throughout the 18th Century.Footnote 45 While at the beginning of the 19th Century, Edinburgh was the second-largest city in Britain, by 1831, it had been overtaken by Glasgow, Liverpool, and Manchester.Footnote 46 Edinburgh's population increased from 168,145 to 185,145 between 1861 and 1871, while Glasgow's population climbed from a significantly larger base of 403,394 to reach 490,000 by 1871.Footnote 47 Edinburgh's much smaller population reflected its unchanged demographic make-up. Its cultural activities remained largely controlled by elites in established institutions, which, as Shapin pointed out, included the Faculty of Advocates; the Society of Writers to His Majesty's Signet; annual meetings of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland; and the Town Council, which controlled the University of Edinburgh and represented 33 craft guilds, including the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons.Footnote 48

Edinburgh thus remained a city whose old, established classes continued to dominate. While Britain's lower middle classes had been establishing a foothold in metropolitan scientific institutions from the mid-19th Century, Edinburgh remained an exception. As late as the 1870s, contributions to the RSE's Transactions were authored exclusively by professors, Fellows of the Royal Society, and titled men of science.Footnote 49 This is not surprising given that the laws of the Society enforced heavy economic and social barriers to access. Revised in October 1871, membership rules stated that every Ordinary Fellow had to pay a total of five guineas within three months of his election, and three guineas annually thereafter for ten years.Footnote 50 Non-resident fellows were required to pay a hefty £26 5s.Footnote 51 As with the Royal Society of London, a candidate's economic capital had to be matched by his social and cultural capital, as he was required to provide a certificate of recommendation signed by at least four other Ordinary Fellows, ‘two of whom shall certify their recommendation from personal knowledge’. The certificate had to state:

A. B., a gentleman well versed in Science (or Polite Literature, as the case may be), being to our knowledge desirous of becoming a Fellow of the RSE, we hereby recommend him as deserving of that honour, and as likely to prove a useful and valuable Member.Footnote 52

Persons ‘eminently distinguished for science or literature’ could also be made Honorary Fellows.Footnote 53 While the process for election was marginally simpler, success hinged upon a candidate possessing the tacit skills required to navigate an elite social network. The candidate then had to be recommended by Council or three Ordinary Fellows, and the proposal communicated viva voce, printed in the circulars for two ordinary meetings, and put to election by ballot.Footnote 54

The RSE's tightly guarded network was reflected in the highly selective distribution of its published Transactions. In Scotland, distribution was limited to the four ancient universities and six Edinburgh libraries, each of which was patronised by a highly elite demographic: the Advocates' Library, College of Physicians, Highland and Agricultural Society, Royal Medical Society, Royal Physical Society, and Royal Scottish Society of Arts.Footnote 55 The Botanical Society of Edinburgh, Geological Society of Edinburgh, Meteorological Society of Edinburgh, and, notably, the Philosophical Society of Glasgow, received the Proceedings only.Footnote 56 The Proceedings would, therefore, have been available to Croll when he worked as janitor of Anderson's College in Glasgow and made unorthodox use of the library where the Philosophical Society's collections were held.Footnote 57 Given his familiarity with this publication, why, then, did Croll choose not to engage with the RSE or its publications during his later career?

Given the RSE's elite social composition, it is unlikely that Croll would ever have been invited to apply for membership and no record exists of him in the RSE's extensive archives. But it is still more likely that Croll would have refused association with the Society had he been invited to join it. Croll's response to an invitation to join another club in 1869 provides some insight into how he might have responded.Footnote 58 The ‘prospectus’ Croll received read:

It has been thought desirable to organise in Edinburgh a CLUB similar to the ‘Cosmopolitan’ and ‘Century’ Clubs in London.

The Members of the Cosmopolitan and Century Clubs are, for the most part, men distinguished in, or at least [displaying] a marked taste for Art, Literature, or Science …

The following list of Gentlemen who have already consented to join the proposed Club, will give some indication of its character and aim …. Footnote 59

Among the list of ‘Gentlemen’ were many Fellows of the RSE, including Sanskrit Scholar, John Muir (1810–82), Curator of the National Gallery James Drummond (1816–77), future Edinburgh MP Robert Wallace (1831–99), and future St Andrews University Principal James Donaldson (1831–1915), as well as 14 advocates.Footnote 60 Edinburgh Professor of Natural Philosophy, Peter Guthrie Tait (1831–1901), was responsible for introducing 70 guests to this elite group of gentlemen, men of science, influential politicians, and intellectuals; they including T. H. Huxley and James Clerk Maxwell when the British Association met in Edinburgh in 1871, and, two years previously, James Croll.Footnote 61

Tait's biographer claimed the association ‘had a direct bearing on scientific activity’, as ‘it was probably in the free and easy conversation of this Evening Club’ that its first treasurer George Barclay and Thomas Stevenson began many of their contributions to the physical sciences.Footnote 62 Correspondence between members provides a rather different image of the organisation's function. In response to Tait's invitation, W. J. Macquorn Rankine replied that he would be ‘very happy to join’ Tait's ‘Capnopneustic Club’.Footnote 63 Referring to the smoky atmosphere for which the Cosmopolitan and Century Clubs were renowned, Rankine's trope was widely shared by members. Another invitee replied that he would be ‘delighted to join if smoking & good listening without much talk will qualify’.Footnote 64 It was well known that Tait's club met on Saturday and Tuesday evenings and on Monday evenings immediately after the RSE's meetings, ‘purely for social intercourse [and] cards and serious subjects of debate being taboo’.Footnote 65

The Century Club, upon which Tait's society was to be modelled, was composed of an extremely narrow social circle, including mostly old Etonians, Harrovians, and Rugbeians, who had typically attended either Balliol College, Oxford, or Trinity College, Cambridge, and became barristers, ‘though not necessarily with a view to practising’.Footnote 66 Renowned as ‘a talking club’, the Century imposed an annual guinea subscription, which included free tobacco, whisky, and brandy.Footnote 67 A much higher contribution was required at Tait's club – £2 annually, to cover all expenses – and the society otherwise proved a good copy of the Century and Cosmopolitan. Nothing could persuade Croll to join its ranks. Croll responded to Tait:

I feel much obliged for the honour of being requested to become a member of a Club so select. At some future time I may think of applying for admission, but in the mean time I cannot make up my mind to do so.Footnote 68

Croll's refusal reflected his vision of science, namely its unification with religion and philosophy. Croll had little time for talking and smoking clubs, having become a teetotaller and given up tobacco around the age of 30.Footnote 69 He found more like-minded practitioners in an institutional network with a very different social structure.

3. Geological Survey of Scotland

Croll's first exposure to scientific societies was gained while working as a janitor. Croll had attended ‘two or perhaps three sessions’ at the Parish School, Cargill, but left ‘about 15 or 16 years of age’.Footnote 70 At the age of 22, he paid to attend a winter course of algebra lessons at a private school in Guildtown, St Martins.Footnote 71 As Croll later wrote, ‘the greater part of my education has however been self acquired’.Footnote 72 At the age of 36, Croll wrote to several professors at the ancient Scottish universities asking for a bursary to study, and sent his first publication, The Philosophy of Theism (1857), as proof of his aims and abilities.Footnote 73 Principal of Glasgow University, Thomas Barclay, sympathised with Croll's ‘desire to have the benefit of a university education’.Footnote 74 With Barclay's assistance, alongside that of James Frederick Ferrier, who was then Professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews, Croll became Keeper of Anderson's College and Museum, part of the University of Glasgow, from 1859 to 1867.Footnote 75 The post came with a salary of almost £100 per annum and accommodation. The Museum was open only between 11am and 3pm and had few visitors; Croll had little to do with arranging or classifying specimens; and he delegated many of his duties to his brother.Footnote 76 Thus, Croll was able to attend George Cary Foster's Natural Philosophy class and immerse himself in the ‘fine scientific library’ of the institution.Footnote 77 The Andersonian housed the entire collection of the Glasgow Philosophical Society; 4000–5000 volumes on science for evening classes; and the private library of the founder of the institution, which consisted of more than 2000 works.Footnote 78

The Andersonian also provided a meeting place for the Geological Society of Glasgow. A ‘Special Notice’ issued by the Society for 1864–1865 directed ‘persons desirous of joining the Society’ to apply to ‘Mr. James Croll, Janitor’.Footnote 79 In March 1866, one year before Croll left his position as janitor, he read his first paper at the Society, ‘On the reason why the change of climate in Canada, since the glacial epoch, has been less complete than in Scotland’.Footnote 80 By 1867, Croll had been elected an Honorary Associate of the Society.Footnote 81 Gaining his first exposure to scientific associationalism by sitting in on meetings as a janitor (and thus presumably avoiding paying subscription fees), Croll's highly unorthodox and egalitarian exposure to scientific societies left him with a view of how scientific institutions ought to operate, which he maintained for the rest of his scientific career.

In 1867, Archibald Geikie, the recently appointed Director of the Geological Survey of Scotland, invited Croll to accept a position with the Survey.Footnote 82 Much like the post Barclay and Ferrier had helped secure for Croll at the Andersonian, the Survey position was to be ‘very easy’ administrative work, its chief purpose to provide a modest income so that Croll could be relatively free to pursue his own geological researches.Footnote 83 The job consisted mainly of forwarding letters, ordering maps, and keeping the accounts. When Croll failed his Civil Service examinations in mathematics and English composition – which had recently been made a necessary requirement for Survey employees – Geikie, Murchison, and William Thomson ensured that this was overlooked.Footnote 84 Croll's rank was technically that of Assistant Geologist and he was paid accordingly, at a rate of 7s. a day, which would rise to 12s. (including Sundays and a month of holidays), with the prospect of later increasing to £350 a year.Footnote 85

Of all scientific institutions, Croll praised the social structure of the Geological Survey most highly. One of the aims of the Survey's founding Director, Henry De la Beche, had been ‘to rid English science of aristocratic favouritism through the adoption of a system of public funding’.Footnote 86 As James Secord has outlined, De la Beche's view of science in England was one in which incompetence and favouritism reigned, as demonstrated by the influence of the aristocracy and Anglican church over the ancient universities.Footnote 87 De la Beche sought to restructure scientific institutions by vesting authority in a ‘professional class of technical experts chosen solely on meritocratic grounds’.Footnote 88 Once the men joined the Survey, De la Beche was renowned for making ‘every effort to weld them into a cohesive social unit’.Footnote 89

By the time Croll joined in the 1860s, the research programme De la Beche built to unite the Survey had all but disappeared, but clubbability remained central to the Survey's philosophy.Footnote 90 In 1869, District Surveyor James Geikie proposed to Geologist Benjamin Peach:

What do you think of starting a club or annual meeting of the Survey fellows (without the Director) to have a quiet and moderate priced supper, where each could do as he chose. The object of the feed being to promote kindliness and a good understanding? I think it would do. It might be the means of doing a vast of good in the future. Should it precede or succeed the Survey Dinner?Footnote 91

The ethos evoked by ‘moderately priced suppers’ and ‘kindliness’ contrasted significantly with Croll's view of the ‘materialistic’ BAAS meetings and the smoking clubs proliferating elsewhere in Edinburgh and London. In much the same way that Croll had been helped by men of the Geological Survey while working as a janitor, so Croll later aided fossil collector, James Bennie. Bennie had devoted his spare time to collecting fossils and studying deposits while working in a paper factory.Footnote 92 After Bennie sent his results to Croll in 1867, Croll helped Bennie publish his findings, and two years later Bennie was recruited to the Survey.Footnote 93 Croll advised Bennie on which classes to attend, noting that ‘Mr [Archibald] Geikie's lectures at the Museum’ – which were held in the evenings to allow members of the public to attend – ‘were the best lectures I have yet heard on physical geology’; Croll criticised Bennie's writing style, directing him to erase sections ‘where you speak in a disparaging sort of way of your own labour’; and Croll helped Bennie ‘add a good few shillings’ to his weekly income after hearing that William Thomson was looking for an assistant, and put in a good word for Bennie.Footnote 94

It was in this spirit of openness and genuine friendship, unaffiliated with materialism and unfettered by sectarian loyalty, that Croll expressed himself most comfortable practising the pursuit of knowledge. In contrast to the persona Croll presented to men of science in print, in his correspondence with philosophical allies he openly styled himself as ‘a plain, self-educated man’.Footnote 95 Croll referred to the men of the Geological Survey – amongst whom Peach, Bennie, and farmer's son John Horne were from similarly humble backgrounds – as ‘our men’ and his ‘geological friends’.Footnote 96 They positioned themselves in opposition to the elite, metropolitan clubs. In 1881, two decades after Geikie proposed the founding of a ‘quiet and moderate’ club, he wrote to Peach:

I am awfully vexed to hear about poor Croll. What a sad eclipse! He is the most philosophical physico-geologist we have had since Hutton. Some day that will be recognized: but not by the present race of funny mannikins [sic.] who preside over the fortunes of the Geological Society of London.Footnote 97

The mid-century usage of ‘mannikin’ was extremely depreciative, referring to a ‘little man’.Footnote 98 Geikie's emasculating depiction contrasts with early 19th-Century accounts of the Geological Society of London's discussions as ‘characterized by manly vigour, tempered always by good manners’.Footnote 99 In the first half of the century, even the fiercest of critics of the London institutions, like natural historian William Swainson, had typically exempted the Geological Society from ‘his general stricture that the republic of science had degenerated into an aristocracy of wealth’.Footnote 100 Although Swainson's characterisation remained a fair assessment of the profile of the Society's presiding officers in 1882, Geikie's vexation was most likely caused by the limitations the Society placed on their recognition of Croll's contributions to science.Footnote 101

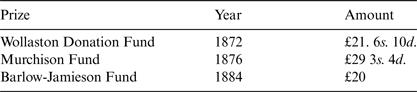

Twice-president of the Geological Society and Director of the Survey from 1855 to 1872, Roderick Murchison had been instrumental in ensuring that Croll's failures in the Civil Service examinations were overlooked, thus enabling Croll to be appointed to the Survey. Murchison did this ‘con amore’ because he recognised that Croll was ‘too wonderful a glacialist’ not to be given the opportunity to pursue his work.Footnote 102 Moreover, Croll was named the recipient of the Wollaston Fund for 1872, which carried a monetary value of £21. 6s. 10d., ‘for his many valuable researches on the Glacial phenomena of Scotland, and to aid in the prosecution of the same’.Footnote 103 In 1876, Fellow of the Society Andrew Crombie Ramsay, then Director of the Survey, was entrusted to transmit the balance of the Society's Murchison Fund to Croll, in ‘the hope of the Council of this Society that it may prove of service to him in the prosecution of those studies with which his name has been so long and so honourably associated’.Footnote 104 While the printed report of the anniversary meeting at which the awards were announced refrained from referring to Croll's personal circumstances, the account published in Nature claimed that Ramsay had remarked:

Mr. Croll's merits as an original thinker are of a very high kind, and that he is all the more deserving of this honour from the circumstance that he has risen to have a well recognised place among men of science without any of the advantages of early scientific training; and the position he now occupies has been won by his own unassisted exertions.Footnote 105

Finally, in 1884, Croll received the Barlow-Jamieson Fund (£20) from the Society, in recognition of ‘the value of Dr James Croll's researches into “The Later History of the Earth,” and to aid him in further researches of like kind’.Footnote 106 Despite being recognised as the intellectual equal of many Fellows and receiving three monetary awards from the Society (Appendix 2), Croll was never elected a Fellow. A very different ‘ambitious expatriate Scot who felt that he rarely met congenial souls even among geologists’, Charles Lyell, had navigated London in the 1830s with ‘singular steadiness of purpose’, making his aim of gaining geological knowledge commensurate with procuring wealth, ‘respect, fame, and command of society’.Footnote 107 For Croll, such ambitions in science were unthinkable, and he sought to stake out his reputation chiefly through his correspondence and published writings.

4. The Philosophical Magazine

The scientific world in the second half of the 19th Century was marked by the enormous proliferation of journals, as writing became ‘yet another aspect of scientific practice’ and key to the emergence of a professional identity for science.Footnote 108 The two publications of the Geological Survey were the Decades and Memoirs, which De la Beche had produced ‘to unite staff under a single banner’.Footnote 109 These journals were reserved for the Survey's results, which served both to encourage a sense of collective endeavour among men of the Geological Survey, and kept the journals from being ‘submerged’ into the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, or ‘other independent, individualist periodicals like Magazine of Natural History or the Philosophical Magazine’.Footnote 110 Once again, Croll defied the expectations of his class, contributing to high-level theoretical debates rather than the fossil collecting in which men of lower social rank typically engaged, or the fieldwork usually published in geological journals.Footnote 111 Of Croll's 92 publications, 38 were printed in the ‘independent, individualist periodical’, the Philosophical Magazine, which was his single most frequent choice of journal.

Croll had already published papers in the Philosophical Magazine while working as janitor at the Andersonian. There were several advantages to the journal's independence from Croll's perspective as a practitioner. As J. J. Thomson reported, ‘I think myself that the Philosophical Magazine is a better means of publication than even the Royal Society as the circulation is larger and the delay very much less’.Footnote 112 Thomson sent papers to the Royal Society only occasionally, ‘as it is usually so long before they are in print that one almost forgets what they are about’.Footnote 113 The Magazine's rapid turnarounds were part of its market strategy, its independence facilitating its self-presentation ‘as a nimble operator and rapid route to publication’.Footnote 114 Its independence and reach also suited someone entering science from a background similar to Thomson's moderately humble beginnings, as ‘those who did not have direct access to the circles of polite society, because of geography or social class, might gain attention and approbation through careful publication’.Footnote 115

To choose a journal simply because if its wide circulation would be dangerously close to the ‘self-assertion’ Croll so disdained in the materialistic men of science. The more significant principle behind Croll's selection of the Philosophical Magazine was more likely its ‘long-established independence’.Footnote 116 As Clarke and Mussell have shown,

although the activities of the learned societies provided useful copy, the success of [the] Philosophical Magazine was predicated on its independence: unaffiliated, its editors were free to reprint content wherever they found it and, without the bureaucracy of the societies, could get papers into print fairly quickly.Footnote 117

Founded in 1798 by journalist and inventor, Alexander Tilloch, the journal ‘established a readership as a monthly miscellany specialising in scientific news and information’.Footnote 118 From 1852, it was published by Taylor & Francis and gradually came to focus exclusively on physics and mathematics. Its front page displayed the names of the leading men of science who served as editors, who included Croll's correspondent, John Tyndall, as well as J. J. Thomson, Nevill Mott, and Croll's patron and fellow member of the Geological Society of Glasgow, William Thomson.Footnote 119

The Philosophical Magazine's independence juxtaposed the nepotism and aimless socialising Croll perceived as characteristic of other journals and the societies who published them. The Philosophical Magazine's editorial policy contrasted significantly with that of its two closest rivals, the Proceedings of the Royal Society and the Proceedings of the Physical Society.Footnote 120 Contributions to the Royal Society's Transactions (1665-) and Proceedings (1832-) first had to be read at a meeting, in person if the author were a Fellow, or by a communicator, before the paper could be considered for publication. In further contrast to the Philosophical Magazine, the Royal Society had a system of referees whose judgement determined whether or not an article would be accepted.Footnote 121 First and foremost a commercial journal, the Philosophical Magazine's lack of societal or institutional affiliation meant that it could publish papers without judgement as to the author's background.Footnote 122

Tyndall, a ‘leading exponent of evolution and scientific naturalism’, was a prominent member of the Philosophical Magazine's editorial board.Footnote 123 Like Huxley, Clifford, and other Darwinians, Tyndall typically chose to publish in The Fortnightly Review, a scientific periodical based upon a non-theological social philosophy.Footnote 124 It was typical of Croll to engage in direct intellectual combat with his opponents, and he frequently sent offprints directly to correspondents likely to disagree with his own views.Footnote 125 Croll began this practice with his first publication in 1857, sending copies of his Calvinist tract to ministers and professors holding a wide range of philosophical convictions.Footnote 126 It seemed to be a custom for which Croll became renowned, as Charles Lyell concluded a letter to John Herschel, in which Lyell discussed Croll's article in the ‘Phil Mag’ for 1865, ‘I daresay he sent you an author's copy’.Footnote 127

Croll continued in this style of intellectual combat to the very end of his career. In 1871, he wrote to the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society:

I wish to send a copy of one of my papers to a few of the members of the Royal Geographical Soc'y but have not their addresses.

If you have a printed List of the names of your members would you be so kind as to favour me with a copy.Footnote 128

Contrary to the practice of many rising men of science in this period, Croll's aim was not to use his publications to navigate his way into elite correspondence networks and be elected to the Society in order to further his own scientific career. Croll's last and, he declared, ‘most important’ work was The Philosophical Basis of Evolution (1890), a preface to which appeared as ‘Evolution by Force Impossible: A New Argument against Materialism’, published in the British Quarterly Review in 1883.Footnote 129 By this time, Croll had lost any kind of institutional access to scientific periodicals and yearned for scientific news. In the spring of 1881, Croll's health had taken a decided turn for the worse. While the Survey encouraged Croll to apply for a prolonged leave of absence, Croll perceived the offer of extended paid leave to be improper, and decided his only option was to retire.Footnote 130

In exchange for providing feedback on their articles, Croll asked the men of the Geological Survey to send him scientific journals.Footnote 131 In December 1881, Croll pleaded with Horne:

As I am cut off from all scientific journals and magazines at present, would you let me have a look at your Athenaeum when you are done with it? I will return it to you next day. I don't read much, but like to look over that journal, more particularly the advertisements part, as it lets one know what is going on in the book world … but I do not like to ask for the office copy.Footnote 132

It was probably very easy for Horne to persuade Geikie to let Croll have the office copy and Croll's request seems to have led to the regular exchange of the journal. In autumn 1882, Croll replied to Horne, ‘I return Athenaeum with many thanks. Look at Literary Gossip for 23rd September’.Footnote 133 There appeared the notice: ‘An article by Dr James Croll, F. R. S., entitled “Evolution in Relation to Force: a New Argument for Theism,” written before his recent illness, will shortly appear in one of the quarterlies.’Footnote 134 Invoking his scientific credentials, ‘F.R.S.’, to assert his authority in matters of theology and philosophy, Croll could not have demonstrated his perception of the pursuit of knowledge as a single, unified vocation any more clearly.

5. Conclusion

Geological Survey

Edinburgh June 5th 1876

Sir,

Your letter of the 2nd inst., informing me that I have had the honour of being elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, I duly received.

I herewith enclose Draft for £14; being £10 for Admission Fee, and £4 for first years [sic.] subscription.

I am sorry I shall not be able to be present at next meeting of the Society

I am, Sir

Your obedient servant

James CrollFootnote 135

For most men of science, this letter would symbolise the zenith of their scientific career, serving as evidence of the recognition their work had been afforded by their peers. Croll's missive conveyed the typical news that he would be absent from any formal presentation of the accolade. I hope by now it is clear from my argument that this was unlikely to be due to the geographical distance between Edinburgh and London alone. In this article, I have situated Croll's navigation of scientific societies in a study of the societies' local cultural contexts; in doing so, I have sought to illuminate significant factors in Croll's unconventional trajectory. He sought an education for theistic ends and purposefully navigated his participation in the emerging scientific community, avoiding opportunities which would have granted him professional status or more material comfort. Perhaps the most apt characterisation of Croll was made in a letter to Croll's biographer during their petition to get Croll a Civil List Pension: the Rev. Joseph Parker stated that Croll was known for his ‘energy’, but lacked ‘the kind of wheedling courtesy that goes so far in spineless London’.Footnote 136

Croll did not conform to the ideal-type of a professional man of science who rose from humble origins to make a scientific career for himself; thus, he cannot be cast in the mould of Faraday, an artisan aspiring to professional status. Croll also did not adhere to a Smilesian trajectory, as an autodidact whose participation in science proved conducive to moral improvement. According to Croll – who was recognised as ‘the most philosophical physico-geologist we have had since Hutton’ – the pursuit of knowledge was measured on a very different scale. Ultimately, Croll – and many like him – resist identification according to historian's ideal-types. While this article has been concerned with James Croll, therefore, its analysis carries broader implications for the history of science. Croll's trajectory calls for more attention to be paid to the ‘obligatory amateurs’, the ‘devotees’, and the ‘cultivators of science’ – terms used to grasp the precarious array of possibilities for non-elite groups who were not afforded gentleman or professional status, to participate in and contribute to the production of knowledge.Footnote 137

In retirement, Croll struggled to access books due to his lack of societal affiliations and suffered from ill health and financial instability. Croll and his wife survived on his pension and her annuity, which amounted to a meagre £83 13s. 4d. Footnote 138 Croll was awarded £130 from two grants from the Royal Society Relief Fund and £100 from the Royal Literary Fund.Footnote 139 A petition was presented to Parliament in an attempt to increase Croll's pension and a subscription raised in his aid, but both failed.Footnote 140 Croll's goal of unifying ‘religion, philosophy, and science’, to turn opponents into allies, and to rid science of its ‘cold materialistic atmosphere’, shaped his self-presentation as he navigated science's institutions. As he lived most of his life in material poverty and remained largely neglected by historians for more than a century, Croll ultimately paid the price for his devout adherence to his unorthodox vision of science.

6. Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Kevin Edwards for the invitation to contribute to this Special Issue and for his keen editorial eye. I would also like to thank Dr Anne Secord for her helpful comments and suggestions and Dr Stuart Mathieson and Professor Simon Naylor for their generous and constructive reviews. I am grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council Cambridge DTP for funding my research.

Several archivists kindly accommodated my research enquiries and I am especially grateful for the assistance of Caroline Lam, Archivist and Records Manager at the Geological Society of London; Emma Yan, of the Archives & Special Collections University of Glasgow; Dr Anne Cameron, Archives Assistant at the University of Strathclyde; Andrew L. Morrison, RMARA Archivist at the British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham; Robert Neller, Collections Officer and IT Manager at Haslemere Educational Museum; Kat Harrington and Chris Olver in the archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Andrea Hart and Paul Martyn Cooper at the Natural History Museum; Julie Carrington at the Royal Geographical Society; Laura Earley at the Royal Society of Edinburgh; and librarians and archivists at the Royal Society; the British Library; St Andrews University Library and Special Collections; Edinburgh University Library; and the National Library of Scotland. My research was brought to light by Mike Robinson and Anne Daniel at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society who generously gave up their time to show me around the birthplace of James Croll in Perthshire.

7. Funding information

AHRC Grant Number: AH/L503897/1.

8. Appendix 1. Croll's Membership of Scientific Societies

Derived from Records of the Geological Society of Glasgow, ACCN 2561/3/1; Irons (Reference Irons1896, p. 39); The Royal Society, GB117, EC/1876/08, ‘Croll, James’; Edinburgh Geological Society (1870, p. 238).

9. Appendix 2. Prizes Croll received from the Geological Society of London

Derived from Evans (Reference Evans1872, pp. 4–5); The Geological Society, GSL/L/R/19/6 Letter from Dr James Croll, 19 February 1872; Evans (Reference Evans1876, p. 5); The Geological Society, GSL/L/R/19/180 Letter from James Croll, 22 February 1876; The Geological Society of London (1884, p. 11).