No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

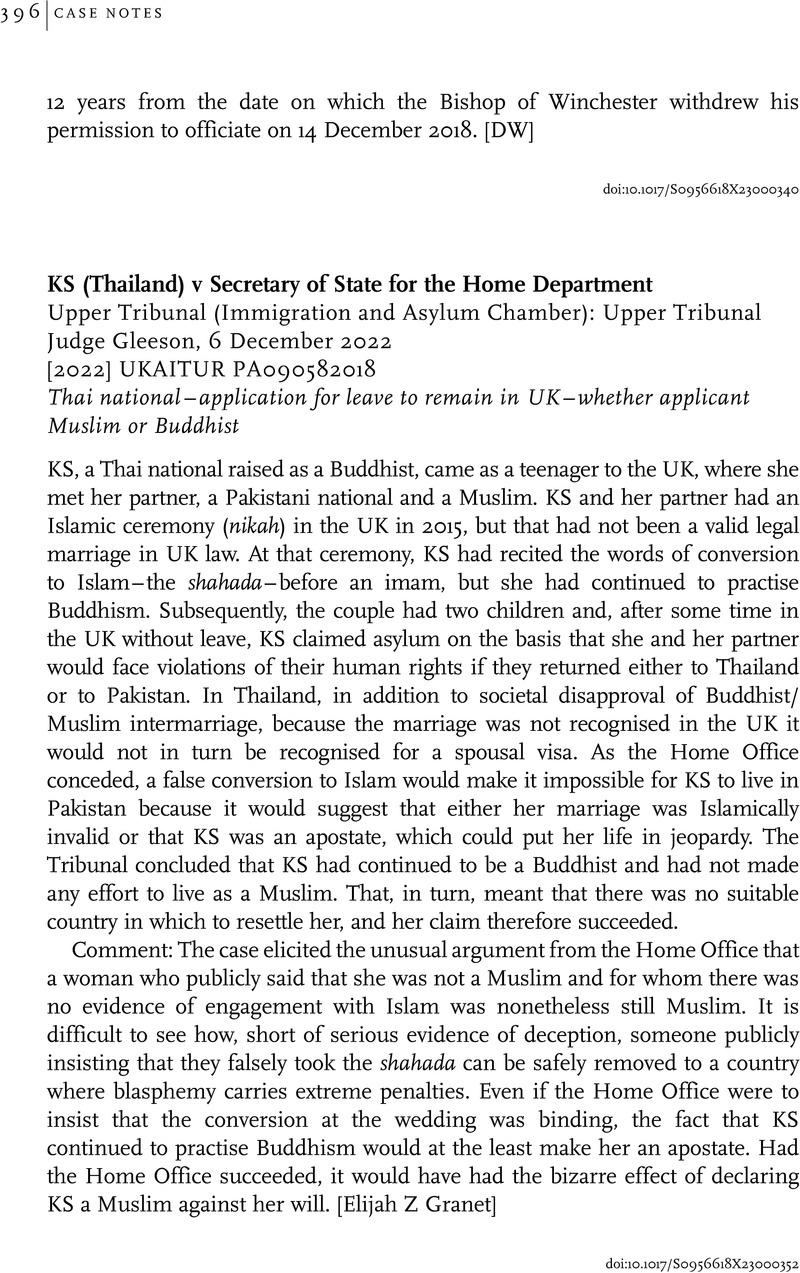

KS (Thailand) v Secretary of State for the Home Department

Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber): Upper Tribunal Judge Gleeson, 6 December 2022[2022] UKAITUR PA090582018Thai national – application for leave to remain in UK – whether applicant Muslim or Buddhist

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Case Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Ecclesiastical Law Society 2023