No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

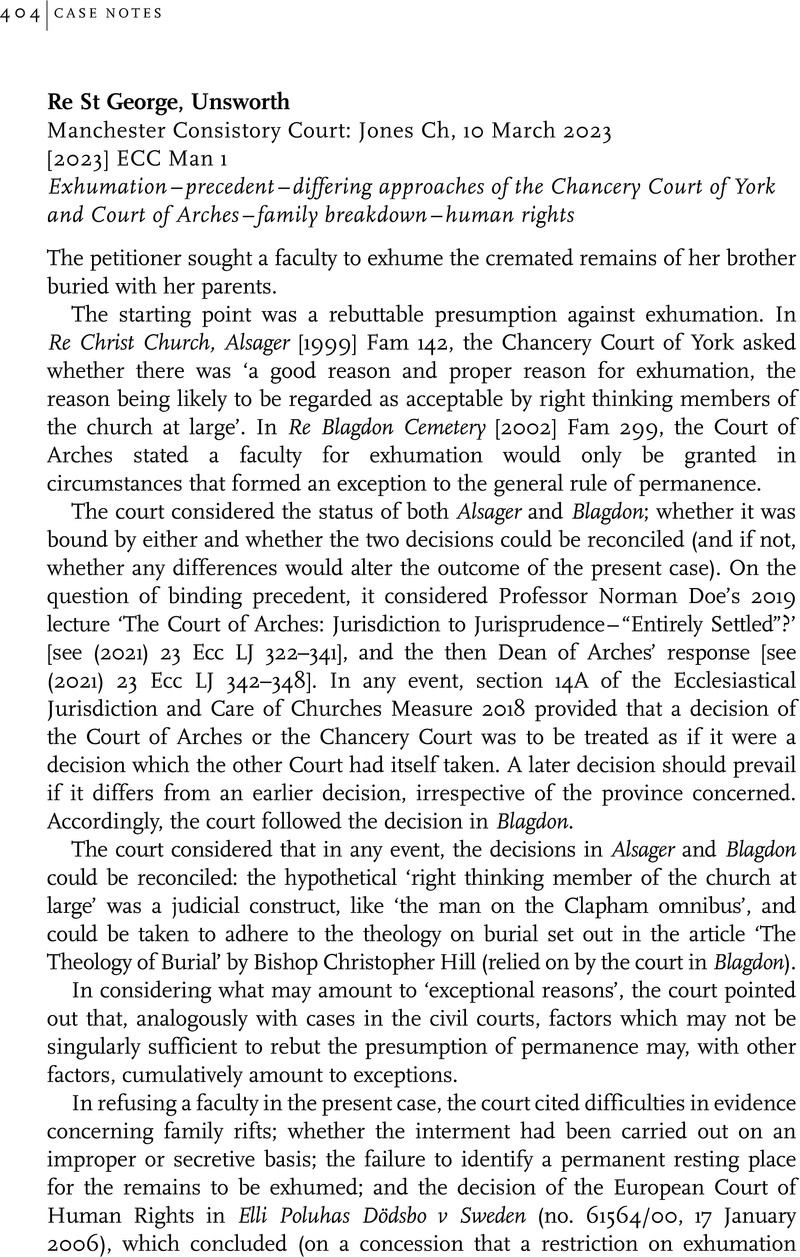

Re St George, Unsworth

Manchester Consistory Court: Jones Ch, 10 March 2023[2023] ECC Man 1Exhumation – precedent – differing approaches of the Chancery Court of York and Court of Arches – family breakdown – human rights

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Case Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Ecclesiastical Law Society 2023