1. Introduction

Creativity in language may be seen as a continuum between what Sampson (Reference Sampson and Hinton2016) characterized as F-Creativity (Fixed Creativity) and E-Creativity (Extending Creativity). F-Creativity takes existing rules and applies them in such a way that novel (linguistic) output is produced. If there is a rule that says that a sentence can be built with a subject noun phrase plus a verb phrase that comprises a transitive verb and an object noun phrase, speakers can form an endless number of sentences, simply by appropriately filling the individual slots: John ate the pizza; Mary kicked the ball; Peter saw a ghost etc. Similarly, relative clauses in English can be used recursively, i.e. a relative clause may contain a relative clause, which may contain another relative clause, and so on. This, at least in theory, allows language users to build an infinite number of sentences (cf. Adger Reference Adger2019: 168). Sampson (Reference Sampson and Hinton2016) characterizes this notion of creativity as Fixed Creativity, as it is ‘merely’ the productive application of rules. For Sampson, this resembles simple maths, where the same sort of rules that tells us that 3×4 equals 12 allows us to calculate 2356×784 (…it’s 1,847,104) even when we’ve never done that before. Sampson wonders whether we really want to call this ‘creativity’ in the original sense.

A little bit further down the cline we find a somewhat different but related kind of ‘creative’ language use, when language users apply existing rules in contexts where they typically should not be applied. For example, in (1) we see an intransitive verb, smile, in a transitive context (smile her way).

Even though examples like (1) feel relatively conventional today, at some point in the history of English the combination must have been new and norm-violating as the intransitive verb smile occurs in a context in which it typically does not occur, namely in a complex transitive pattern with her way as direct object and a directional prepositional phrase out the door. It seems like this kind of creativity is somewhat more creative in the traditional sense (and hence less F-creative) than the first examples from syntax. On a cline, it comes closer to what Sampson termed E-(extending or expanding) creativity, which enlarges the range of possible products for a given activity.

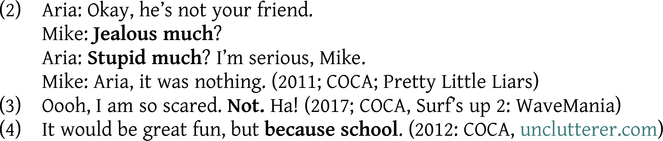

Even further down the cline we may find creative innovations such as (2) to (4).

In (2) we see what could be called the adj-much construction, i.e., an adjective followed by the indefinite quantifier much, rather than the conventional combination of indefinite quantifier and mass noun: much money, much beer, or the combination of noun plus much in particular kinds of phrases such as home much, which may be an elliptical form of home much of the time (cf. Hilpert & Bourgeois Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020).

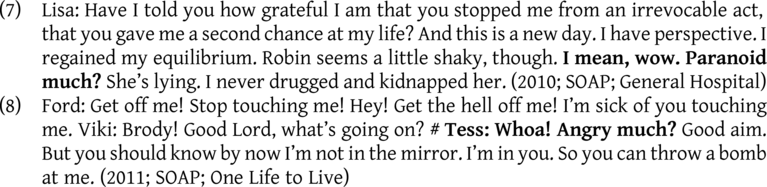

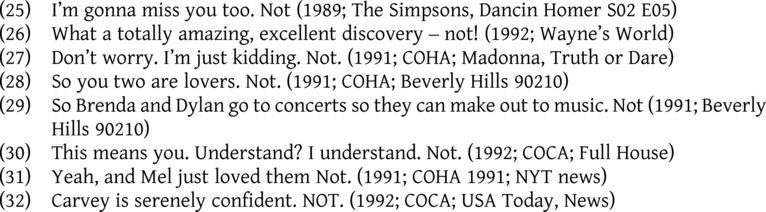

In (3) we find extrasentential not, i.e. the negator not outside a sentence, as the sole element in the utterance, rather than inside a verb phrase, semi-attached or in combination with an auxiliary or modal: I do not / don’t like bean soup (cf. Pullum & Huddleston Reference Pullum, Huddleston, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 812).

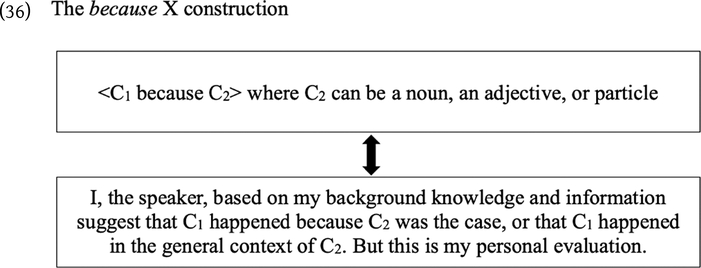

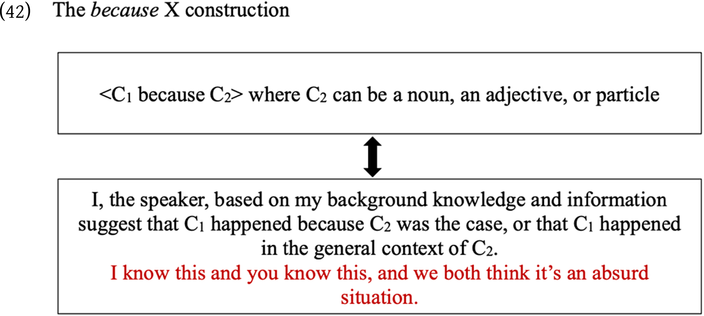

Example (4) shows the because X construction, where because is not complemented by a full clause or an of-prepositional phrase (because I can’t read that; because of the snow), but by a simple noun, adjective, interjection and the like (cf. Bergs Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuna-Farina and Martínez2018).

It would be difficult to argue that these constructions simply result from applying any particular rules like recursive relative clauses, or by violating specific constraints in applying certain rules as in smile your way. And neither should they be seen as mistakes in language use, or glitches in performance. Innovations such as these may not be part of daily language use, but they are not extremely infrequent either. Using the search queries ‘adj.all much ?’, ‘. Not .’ and ‘because noun.all .’ we find about 80 occurrences of adj-much, about 130 occurrences of extrasentential not and several dozen occurrences of because X in the Corpus of Contemporary American English with approximately 1 billion words. Because science now even has its own YouTube channel (@becausescience) and website: https://becausesciencedc.com. We suspect that these three phenomena are deliberate and creative innovations in language that go beyond applying or misapplying rules. It may be debatable whether these actually qualify as instances of E-Creativity as such (cf. Bergs & Kompa Reference Bergs and Kompa2020), but they certainly qualify as the most creative and innovative linguistic behavior out of the three types discussed so far.

This mostly theoretically oriented and hypothesis-generating article focuses on the conceptual problem of syntactic creativity, with phenomena (2)–(4), i.e., the adj-much construction, extrasentential not, and the because X construction as illustrations. How do these innovations come about? From a mostly qualitative point of view, this article discusses the mechanisms and contexts that motivate ‘unusual’ syntactic innovations such as (2)–(4) and the kind of communicative behavior that characterizes their innovators and propagators.

2. Syntactic creativity

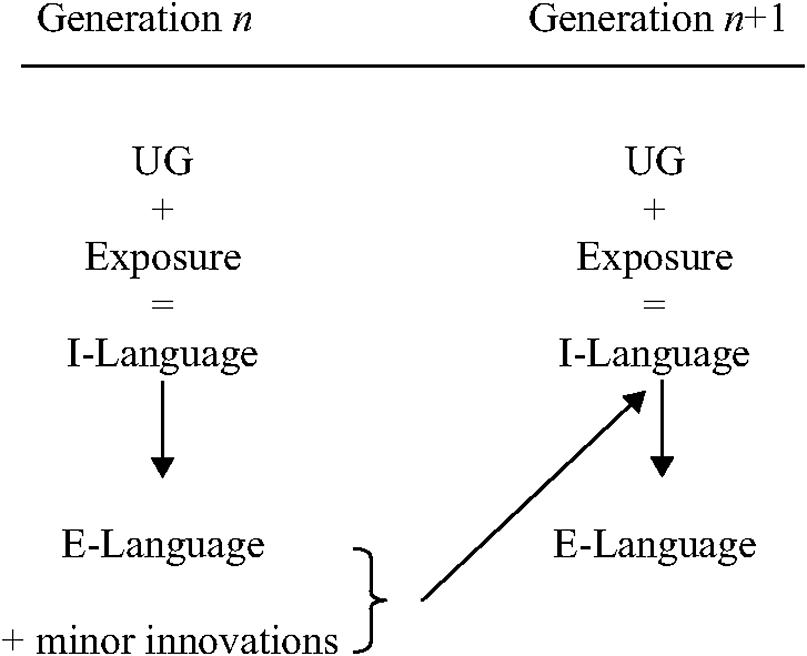

Syntactic creativity and innovation are traditionally seen in the context of rule-based grammars (cf. Adger 2018; Yang Reference Yang2016). According to generative approaches, for example, syntactic innovation typically happens when children in first language acquisition reanalyze the input they perceive and, through abduction, arrive at a different grammar than that of the previous generation (King Reference King1969; Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1999; Andersen Reference Andersen1973; van Gelderen Reference Van Gelderen, Kytö and Pahta2016). This may certainly be one of the major sources of grammatical change. So, for example, in figure 1 generation n has its universal grammar and is exposed to a certain linguistic input. This together forms the basis for the I-language of speakers from generation n, which in turn is the basis for their E-language.Footnote 1 This E-language, together with some ‘minor innovations’, forms the input (exposure) for generation n+1, which runs through the same cycle again, producing the input for generation n+2, and so on. The ‘minor innovations’ in this model could be, for instance, the wear and tear that we see on inflectional suffixes (Old English stan-e ‘stone’ (dative singular) > Present-day English stone-ø), or the coalescence of certain elements (like want to > wanna, have to > hafta). Most of these innovations are fairly regular and perfectly explicable with general principles of language change. With their exposure to the E-Language of previous generations and UG, children build their own I-Language. In doing so, they may not perfectly replicate the grammar that produced the output they were exposed to. If they did, we would find only very little change happening. The two major mechanisms that may influence their grammar in the making are reanalysis and abduction.

Figure 1. Language acquisition and language change, generative models (based on Andersen Reference Andersen1973; van Gelderen Reference Van Gelderen, Kytö and Pahta2016)

Reanalysis, in a nutshell, is the new analysis (rebracketing) of a possibly ambiguous structure. We can find this on the level of morphology, e.g. Middle English a napperon ‘apron’ > Present-day English an apron, and also on the level of syntax, e.g. let us (‘let us go’) > let’s (‘let’s go’) > lets (‘lets you and I go’). Abduction, in a nutshell again, is the hearer’s (re-)construction of a grammar that may have produced the perceived output. So, if hearers of generation II in (first) language acquisition, out of sheer statistical coincidence, only encounter simple SVX structures when talking to speakers of generation I, they may be led to assume that the underlying grammatical system that produced these utterances is essentially verb second (V2), like modern German. This becomes part of their new grammar. It is only when they accidentally hear something like Yesterday they bought a Porsche (AdvSVO) that they may come to the conclusion that the underlying system is not verb second, but actually (X)SV, like modern English.

The problem is that neither reanalysis nor abduction, nor the minor innovations described above can easily explain the novel structures in (2)–(4), as we will show in the following sections. Much in Present-day English usually only occurs in pre-adjectival position, so that rebracketing is not an option. There are certain bridging contexts, i.e. contexts in which much appears in sentence final position (e.g. They appreciate it much), which may motivate the new construction, but it has been argued that, e.g. operator ellipses and reanalysis may not be the source for the novel structure (see section 3 below for details). Similarly, not should never, or at least not frequently, occur outside a full sentence, so that simple rebracketing and reanalysis are again out of the question, even though – just like with adj-much – we find certain bridging contexts and similar syntactic phenomena with items like always or never, which may also occur independently (see section 4 below). Because X may be the result of some ellipses and concomitant reanalysis, however, this is also fairly unlikely (see section 5 below). Moreover, and this is important, from what we can tell, these structures hardly if ever occur in child speech, i.e. during or right after first language acquisition, which is when we would expect reanalysis or abduction to take place. Rather, they appear to be typical for language professionals, such as scriptwriters and stand-up comedians, as well as teenagers and young adults, who are past their first language acquisition phase.

So how do these structures come into being? This article argues that what all these new structures have in common is that they are based on the complex interplay of pragmatic, semantic and syntactic factors. Their innovation and propagation seems to be motivated by Gestalt-like gestures that recycle and blend existing, similar constructions in novel contexts and functions while the basic semantics remain intact. adj-much is still about a high degree of something; not still signifies negation; and because X is linked to causation in the widest sense. Yet all three constructions appear to be loaded with very special pragmatic meaning and functions, and this is possibly where we find their origin. Out of pragmatic considerations, speakers may manipulate syntactic material in such a way that the core semantics remain intact while syntactic constraints are violated – perhaps as a Gricean marker calling for attention and reinterpretation – and a special layer of pragmatics can thus be added. The following sections will look at this from the perspective of the three constructions in question. The analyses will be couched in usage-based Construction Grammar terms (see, e.g., Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022) as constructions, by definition, incorporate syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information without prioritizing any of these (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022: 41f; 238–43). It thus becomes possible to model processes such as the adding of pragmatic extra information, and the conventionalization of extra pragmatic meaning as constructional information (cf. Lehmann & Bergs Reference Lehmann and Bergs2021).

3. The X-much construction

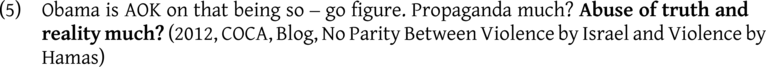

Evaluative or expressive usages of adj -much? combinations as in (2) above have received some attention from various perspectives (e.g. Adams Reference Adams2003; Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Carmichael and Schwenter2011; Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2015, Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019; Hilpert & Bourgeois Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020; Ronan Reference Ronan, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Pahta2019). They all agree that this is a highly colloquial construction, mainly found in informal language use and dialogues. Its main function is to ‘convey a critical or sarcastic meaning, often in response to an utterance by another’ (Hilpert & Bourgeois Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020: 97). As the X-slot does not have to be filled by adjectives only, but can also contain other phrases, as in (5), or even entire clauses, we will henceforth refer to the construction in this article as the X-much? construction.Footnote 2 X-much? utterances imply a ‘critical evaluation’ (cf. Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Carmichael and Schwenter2011), which is conventionalized and non-compositional and thus posing a construction in a Construction Grammar (CxG) sense (cf. Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Carmichael and Schwenter2011; Hilpert & Bourgeois Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020). Gutzmann & Henderson (Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 108) point out that X-much? utterances are ‘neither questions nor assertions, but expressive utterances, akin to slurs or interjections’, despite their interrogative speech contour.

The meaning of much in such constructions is that of ‘often’ or ‘a lot’. Other functions of quantifier much include modifying NPs or PPs as well as functioning as a comparative modifier (for a more detailed overview see Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 110). Hilpert & Bourgeois (Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020: 101) argue that in X-much? constructions ‘[the canonical] meaning [of ‘a lot’] is coerced into ‘excessively’, and a negative judgement is attached to it’.

Examples such as (5) suggest that the construction as such is fairly productive, i.e. available to speakers for the creation of novel combinations. Note, however, that many combinations have semantically ‘negative’ adjectives as their head (racist, jealous, paranoid etc.), an observation also supported by Ronan’s corpus study of X-much? (2019). This seems to be in line with the overall pragmatic undertone of the construction, which is one of reproach and bewilderment, roughly speaking

Regarding the syntactic development of the construction, it has been suggested that it may be related to VP-much utterances, as in they don’t argue much, where much appears in post-predicate position (Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 108) and thus could be the result of operator ellipsis. However, Gutzmann & Henderson’s analysis provides syntactic and semantic arguments, showing that while we can give the much that appears in the X-much construction a familiar scale-based lexical semantics (e.g. Rett Reference Rett2014; Solt Reference Solt2015), the X-much construction is novel and cannot be reduced to other familiar constructions which much, including VP-much (Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 108).

So while X-much? is probably not a simple case of reanalysis, it still may be motivated by particular, regular structures such as VP-much (drink much) or VP NP-much as (6).

Structures such as VP-much or enjoy/like/love/hate NP-much are not particularly rare, and they show in terms of priming that much can occur sentence finally. Priming in this case non-technically describes the fact that speakers may experience much in sentence-final position, which in turn may prime (or motivate) them to use it in the same position in other, novel constructions as well, such as racist much? If we assume that the semantics of much is kept constant, speakers may also be motivated to deliberately use that construction in a post-adjectival position to essentially signify something like Are you jealous a lot? or Are you very jealous? with a new and pragmatically interesting twist. This new structure may thus be blending and recycling other constructions on the basis of the synonymy of much and a lot plus the regularly occurring VP much and enjoy/like/love/hate NP much patterns. Hilpert & Bourgeois (Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020: 108) also discuss the link between questions and X-much? in more detail, postulating a continuum with expressions like Enjoying your police state much?, which are easily expandible to a full question, to occurrences such as Stupid much?, at the other end of the continuum, which do not have a proper question counterpart.

Potentially, the link to the emotional verbs addressed above and semantically negative adjectives is underscored by the fact that in all corpora investigated here X-much? is often preceded by exclamative interjections, such as woah, wow, jeez, gee, ah, oh, god, oh my, oh dear or lol (see examples (7) and (8)). This indicates that X-much? expresses an attitude of, for example, surprise, annoyance or doubt. Ronan (Reference Ronan, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Pahta2019) also notes that the adjectives which most strongly collocated with much were all expressing a mental state and suggests that this semantic type of adjective, expressing mental state, formed a linguistic prototype from which the construction then extended towards other collocations.

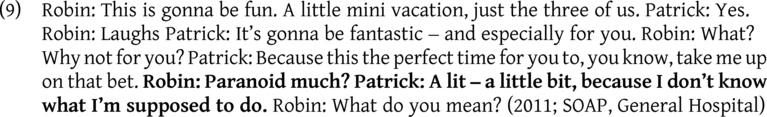

Interestingly, whereas most uses of X-much?, especially the expressive ones, do not function as a question requesting information (Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 108), there are instances which allow for the addressee to respond, though this is probably not intended by the speaker, as in (9). Hilpert & Bourgeois (Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020: 107) also discuss ‘examples that illustrate bridging contexts between ordinary requests for information and sarcastic commentary’, such as Procrastinate much? in a headline.

In (9) X-much? is probably not intended as a question by the speaker, but the hearer’s reaction shows that they feel the possibility and perhaps the need to answer. This might also be a reanalysis on the interlocutors’ (actually scriptwriter’s) part. Especially when X-much? is directed at a person present, a response seems acceptable, in contrast to the commenting function on an individual or object not present, which is the primary construction observable in Gutzmann & Henderson’s (Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2015) examples from comic books and social media. So it stands to reason that these constructions – elliptical questions with meaning or function ambiguous between request for information and simple commentary – may have formed the bridging contexts that helped in the development of the new X-much? construction, which now appears to be a new construction, more or less independent from this source construction.

Hilpert & Bourgeois (Reference Hilpert and Bourgeois2020: 113) also observe that the new construction seems to be expanding further in function from confrontation-seeking to one that ‘is seeking solidarity and alignment of the addressee’.

More importantly for the argument of the present article than the exact constructionalization process is that the use and spread of X-much? involves at least some conscious endeavor by language users as an instance of syntactic creativity. This hypothesis might be supported by the fact that the origin and spread of X-much, at least in the corpora used here, is typically associated with media language, and the language of TV-shows in particular.

It has been suggested before that X-much? spread into colloquial English via TV-shows (Adams Reference Adams2003: 75). According to Adams adj -much was first used in Heathers in 1989 (according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) there is an even earlier occurrence)Footnote 3 and is then frequently found in in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (film 1992, series 1997–2003), Adams’ area of expertise. Adams claims that

it has become a signature feature of slayer slang: ‘Morbid much?’; ‘Insane much?’ … are all mildly outrageous sentences. Neither parents nor teachers gave anyone permission to speak this way; such innovations, as Whitman said, are the poetry of the moment, and because poetry deliberately sees and says things different from the quotidian way, it always taunts convention, even as it exploits it. (Adams Reference Adams2003: 75)

Slayer slang (the language used in Buffy) also features noun -much constructions. Examples such as God, tuna much? do not relate to the quantity of tuna on someone’s sandwich, but ‘it challenges the very state of affairs, that someone would bring a tuna sandwich to the high school cafeteria at all’ (Adams Reference Adams2003: 76). verb -much is another construction the Buffy screenwriters also already experimented with (Adams Reference Adams2003: 90). In 2000 the first noun -much combination was aired on Buffy; however, there were other instances of noun -much constructions outside the Buffyverse before that. Which is why Adams concludes that ‘[t]he development of much had come full circle: the show, originally the imitator, became the imitated, but ended up imitating forms that had imitated it’ (2003: 93).

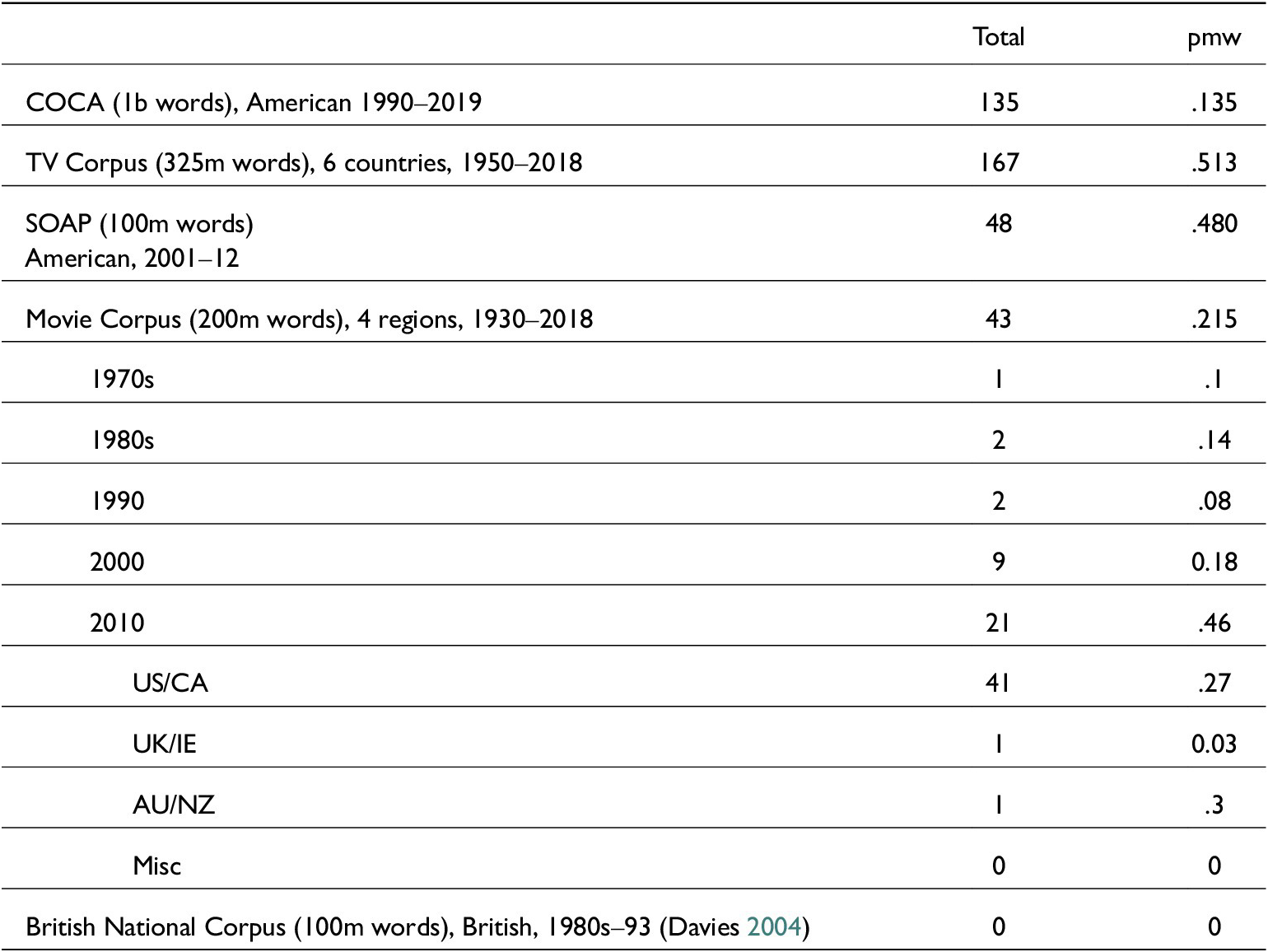

A rough overview of corpora occurrences of adj -much? confirms that the construction still appears a lot more frequently in corpora that reflect media language (and TV in particular). Table 1 shows the distribution of the construction in the different corpora investigated here (see fn. 2 above).

Table 1. adj-much? in five different corpora

This impression is again confirmed when we look at the individual subcorpora of the Corpus of Contemporary American English. Here we find 49 tokens (.383 pmw) of adj-much? in the TV/movies section, 41 (.326 pmw) in the blogs section, 14 (.117) in the fiction section, and none in the spoken language component, even though adj-much? certainly is a (conceptually) spoken and informal phenomenon. The distribution, however, suggests that it may rather be a marker of recent North American media language, e.g. TV, movies, blogs, but also comic books and social media (cf. Gutzmann & Henderson Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2015).

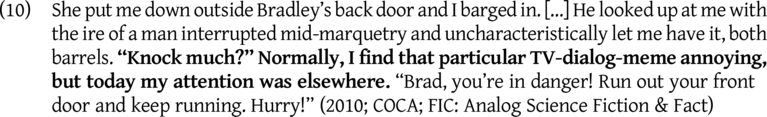

Although the construction seems to have long left the TV-series shelf and has spread into colloquial (but often still computer-mediated) language, the association with its origin seems to prevail at least for some speakers. Example (10) alludes to the fact that the construction is (still) closely linked to conversations in TV-shows:

That the construction involves bending syntactic rules in a creative manner and that it needs some familiarity with it to process its meaning correctly, is supported by Gutzmann & Henderson’s (Reference Gutzmann and Henderson2019: 107) observation that ‘it is possible to find English speakers who do not control the construction [even though] it is not particularly new’.

Ultimately, we can only speculate about the true reasons for creating novel linguistic expressions for the sake of a TV show. Apart from attention grabbing, as the viewers must reevaluate the expression in a Gricean sense, the creators also contribute to the branding of the series. Adams assumes that the scripwriter of the 1992 Buffy film, was probably aware of the use of much in Heathers, as he experimented with verb-much in the Buffy film in 1992, but in the second episode of the series ‘[he] had smoothed out his approach to much and arrived at the adjective collocation’ (2003: 90). Subsequent scriptwriters either still imitated Heathers or the first uses of much in Buffy, but they did not stop at imitation, ‘writers hadn’t given up the notion that something innovative could be accomplished with verb+much’ (Adams Reference Adams2003: 90). Being a successful expression in a successful (and long-running) TV-show, it is not surprising that adj-much? in particular spread into other shows and media usages and was at least to some extent/in some contexts even adopted by ‘real’ speakers.

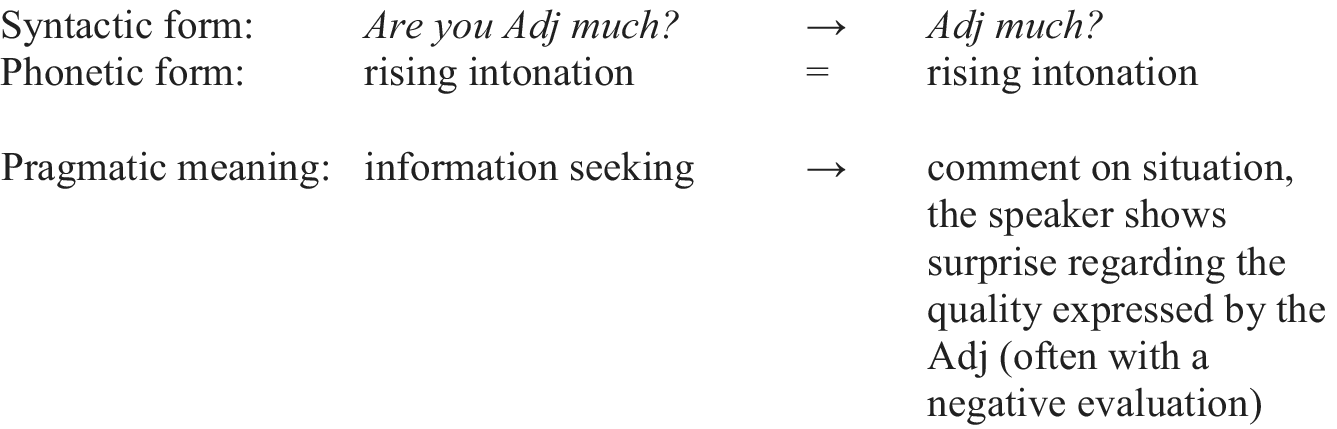

In the conscious creation of adj -much? the scriptwriters had to not only actively manipulate syntactic rules and established patterns, but also make sure that the pragmatic meaning side of the construction changed from a genuine question to that of a comment that expresses surprise and often a negative evaluation of a behavior. Figure 2 illustrates these changes:

Figure 2. Developing an X-much? construction

Bending syntactic patterns and expectations seems to be especially conducive for creating a particular, noticeable (TV-)slang. Targeting a specific audience in the creation of novel expressions might help to establish the constructions and facilitate their spread into speech communities: viewers will use the novel constructions to (indirectly) refer to the show, possibly in acts of identity or as language use in communities of practice. This may be particularly important if the show is regarded as ‘cool’ and has an adolescent audience, as adolescent speakers tend to pick up non-standard/novel usages more readily. As Bednarek notes: ‘some TV series are lauded for invention, creativity, and play, and series with young adults who are close friends will include a high degree of linguistic innovation’ (Reference Bednarek2018: 61).

4. Extrasentential not

Extrasentential not occurs independently, outside a sentence. It does not, for instance, interrupt other phrases as in *Don’t step on NOT my blue suede shoes. Pullum & Huddleston (Reference Pullum, Huddleston, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 812) already noticed the phenomenon and call it ‘unintegrated final not’. They comment:

This construction is found mainly in younger generation speech (popularized and perhaps originated by characters in an American television comedy sketch) but is occasionally echoed in recent journalistic writing. As a humorous way to signal irony or insincerity, a final emphatic not is added following a clause, retracting the assertion made. (Pullum & Huddleston Reference Pullum, Huddleston, Huddleston and Pullum2002: 812)

In COCA, we find about 130 occurrences of extrasentential not. Footnote 4 Extrasentential not negates a preceding positive (or neutral) statement. Repetitive, reinforcing not as in (11) is not included here.

In contrast, extrasentential not typically occurs after short, syntactically positive statements as in (12) and (13).

But extrasentential not can also be found following longer structures, as in (14) and (15).

In extrasentential not, the semantics of not as a negator is kept intact, but it is no longer embedded in a sentence. Rather, as an independent element, it negates or retracts the preceding statement, for example, single items or phrases as in (12) and (13), or more complex utterances as in (14) and (15). Typically, extrasentential not would also be a phonetically very noticeable, stressed and often phonetically elongated element. This means that both syntactically and phonetically, as a standalone element, it attracts special attention and gains some peculiar weight and pragmatic function. The previous statement first suggests some good or positive message, which is then suddenly and surprisingly negated and retracted by extrasentential not. This creates an effect or surprise and also a certain level of irony or sarcasm. Compare the minimal pair in (16) and (17).

Both (16) and (17) begin with the same, seemingly positive, if somewhat exaggerated message: These people are the best of the best of the best. In (16) the following perfectly grammatical utterance They are not then negates the previous statement. Pragmatically speaking, it is decidedly odd to cancel a previous statement like this; the result sounds almost nonsensical and would require some very special clues in pronunciation or facial expression and gesture to make this contextually acceptable. Example (17), on the other hand, also has the negation following the previous positive statement. But this time this is ‘ungrammatical’ extrasentential not. As this has the special pragmatic undertone of being particularly ironic or sarcastic, for example, it makes the whole sequence of utterances much more acceptable and plausible. It is almost as if the positive statement were a quote, or at least an evaluation, from a third party, which is then negated and ridiculed by the speaker.

It is very difficult to determine how exactly this structure came into being. One plausible scenario could be this. Speakers have isolated not as a construction at their disposal to signal negation. This, for instance, is used readily and frequently in reinforcing, repetitive contexts, for the sake of emphasis, as in (11), repeated here as (18), and in (19)–(20).

In (18)–(20), speakers apparently isolate not in the first full sentence as the carrier of negative polarity. We may posit a resulting construction as in (21)

This construction, isolated not, is then used to emphasize the negation in the preceding utterance, much like multiple negatives emphasize negation. This is further supported by the availability of not as a fully grammatical, but prosodically and syntactically isolated/emphasized negator, and non-verbal negator, as in (22)–(24).

Examples such as (18)–(24) may again serve as Gestalt-like exemplars or bridging contexts for creative speakers that enable them to develop a novel, and yet interpretable structure. The creative innovation is the combination of a positive first statement with isolated, negative not. This new combination creates an effect of surprisal and unexpectedness. At the same time, retracting a previous positive statement is, pragmatically speaking, dispreferred and awkward, which leads to the ironic, humorous and sometimes also slightly aggressive undertone. In any case, it creates a highly noticeable new structure.

Like with X-much and in line with what Pullum & Huddleston (Reference Pullum, Huddleston, Huddleston and Pullum2002) already suspected, we find the first (and most) occurrences of extrasentential not in the media language sections of our corpora, particularly in the wildly popular movie Wayne’s World (1992), as well as the equally successful TV series The Simpsons and Beverly Hills 90210. The urban legend that the construction actually originated from the infamous Wayne’s World is probably not true, as an earlier occurrence can be found in The Simpsons (1989). Nevertheless, Wayne’s World certainly was a major promoter of the construction.

Interestingly, Mike Myers, actor and scriptwriter for the Wayne’s World movie, commented on the use of extrasentential not in an 25th anniversary interview in 2017 (www.vulture.com/2017/02/mike-myers-talks-waynes-world-not-joke-snl-trump.html). Asked by the interviewer whether he wrote ‘that joke’ or observed it first, Myers says that he first observed and used that as an adolescent in Ontario. In other words, he denies actively having ‘engineered’ that structure. Moreover, Myers also points out in the interview that the structure is an expression of 1990s sarcasm: ‘I’m going to comply with you, but I am not really complying with you. That would be the mathematics of it.’ The interviewer finally points out that ‘it’s a really simple construction that can turn anyone into a comedian, so long as they follow the formular. You lead someone down – a path and – ’ ‘There is the final negation. Yeah, I do love when things have a home version’, Myers answers.

In sum, we may suspect that the use of extrasentential not, just like X-much, follows Keller’s idea of extravagance: ‘Talk in such a way that you are noticed’ (Keller Reference Keller1994; cf. Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1999: 1055) or at least his maxim of wittiness ‘Talk in an amusing, funny, etc. way’ (for more details, see section 6 below). Media language, i.e. the language we find on TV shows, movies, blogs and the internet, is particularly liable to be extravagant, as being noticed is one of the prime maxims in these media: being noticed, rather than just being part of the group is valuable here. The TV shows in which we find most occurrences of extrasentential not are geared towards teenagers and young adults. For this particular age group, breaking rules, being funny, witty and extravagant carries a particular value, as outlined by Myers. The shows and the characters on those shows are portrayed as being witty, ironic rule breakers, worth imitating. So on the basis of these media, we see early adopters that take the innovation into the different communities and attach a certain value to it.Footnote 5 Those who use these novel constructions, X-much and extrasentential not, are the innovators, witty and clever, the cool kids, leaders of the pack. And from here on we witness the spread of these constructions into the different communities, as markers of extravagance and humor, but also of solidarity and as in-group codes for communities of practice. We also witness occurrences in news coverage and in journalistic writing, see (31) and (32) above, as Pullum & Huddleston mention. Here, they serve the function of being subjective, ironic, amusing and noteworthy. The journalists using these forms probably do so deliberately in an attempt at being amusing, noteworthy, witty and fashionable in their manner of speaking – not unlike Myers in Wayne’s World.

5. Because X

Because X shows a more or less regular syntactic pattern and ‘only’ lacks of, syntactically speaking. Because in this case may be followed by various material: NPs, AdjPs, compressed clauses (e.g. yolo) and interjections of all kinds (e.g. duh); cf. Schnoebelen (Reference Schnoebelen2014). For reasons of simplicity, we will focus on NPs and AdjPs in this article, the most common (and oldest) slot fillers in this construction (cf. Bergs Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuna-Farina and Martínez2018). Even though because X at first sight looks like an elliptical structure, it clearly is not, as the internet meme (33) discussed in Bailey (Reference Bailey2020) shows.

The intended meaning in (33) is something like ‘Why can’t your Prius do this?’ – ‘Because this [in the picture] is a race car’ or ‘Because it [the Prius] is not a race car [like the one in the picture].’ The corresponding grammatical, non-elliptical structures for (33) – *because of (a) race car and *because it is a race car – are not acceptable or don’t make sense in this particular case.

In the same way that much in X-much still carries some quantificational reading, and not in extrasentential not still signifies negation, because in both constructions still signals some sort of causative link, broadly construed (cf. Sweetser Reference Sweetser1990: 77). But, just like the two constructions discussed above, because X has additional pragmatic overtones and is not synonymous with because of X, as can be seen in (34) and (35).

Bergs (Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuna-Farina and Martínez2018) argues that because X adds extra pragmatic meaning to the utterance, such as subjectivity or even sarcasm. Because headache in (35) presents not only the reason for going home itself (as (34) does), but also the fact that this is the speaker’s personal and subjective evaluation of the situation (cf. Keller Reference Keller, Stein and Wright1995). In line with Bolinger’s (Reference Bolinger1968: 127) and Goldberg’s (Reference Goldberg1995: 67) principle of no synonymy (‘[i]f two constructions are syntactically distinct, they must be semantically or pragmatically distinct’ (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995: 67)), because of and because X in (34) and (35) do not appear to be synonymous. Example (35) presents a more subjective viewpoint of the events than (34). The resulting construction is shown in (36).

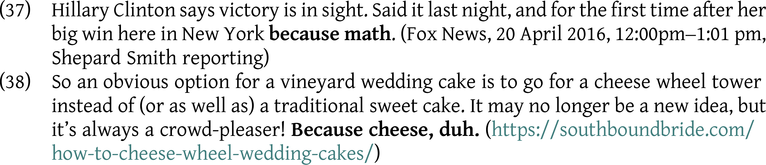

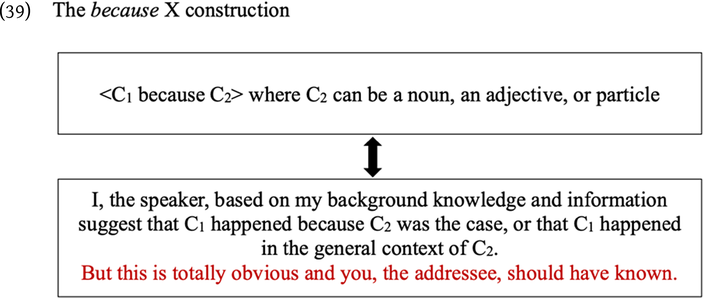

Some more recent examples of because X seem to suggest some extra meaning that goes beyond subjectivity. In (37) and (38) we find two examples where there is not only subjectivity as in (33), but also a certain amount of verbal aggression towards the hearer. The meaning is expanded in the sense of ‘this is the reason, and this is obvious, and you, the addressee, should have known’. This may also be underscored by intonation and possibly facial expressions like raised eyebrows. The extra verbal element duh in (38) also has a similar effect.

This new reading includes the perspective of the addressee, and so moves from subjectivity to intersubjectivity: intersubjectivity is

the explicit expression of the SP/W’s [speaker/writer’s] attention to the ‘self’ of addressee/reader in both an epistemic sense (paying attention to the content of what is said) and in a more social sense (paying attention to their ‘face’ or ‘image needs’ associated with social stance an identity. (Traugott Reference Traugott and Hickey2003: 128)

The verbal aggression expressed here is directed towards and threatening the addressee’s face. Similarly, Traugott (Reference Traugott, Davidse, Vandelanotte and Cuyckens2010) mentions the intersubjective use of certain emphatics for aggression: ‘being “in” rather than “saving” Addressee’s face’ (Traugott Reference Traugott, Davidse, Vandelanotte and Cuyckens2010: 52). The resulting construction can be found in (39).

Interestingly, this sort of intersubjective verbal aggression may also be directed at third parties. By adding this extra (inter)subjectivity, speakers and hearers may also build some common perspective, some rapport, which cannot be achieved with regular because (cf. Kanetani & Cappelle Reference Kanetani and Cappelle2024; Kanetani Reference Kanetani2024; Traugott p.c.). Here, as in (40) and (41), the speakers’ and the addressees’ points of view appear to be fused and aligned, in an act of camaraderie or solidarity.Footnote 6

In both (40) and (41) the speakers on the one hand express their personal, subjective view, while at the same time joining ranks with the addressee in their frustration about these absurd decisions. ‘Liability’ functions like a quote from a third party (that put up the fence and fired the lifeguard… ‘because liability’), whose face is being threatened here. The construction, once more, is represented in (42).

While the actual because X construction may be traced back several centuries (see Bergs Reference Bergs, Seoane, Acuna-Farina and Martínez2018), the first modern and productive occurrences can be found in our corpora from the early 2000s onwards. This may also be the reason for the American Dialect Society making it their Word of the Year 2013:

[t]his past year, the very old word because exploded with new grammatical possibilities in informal online use, … No longer does because have to be followed by of or a full clause. Now one often sees tersely worded rationales like ‘because science’ or ‘because reasons’. You might not go to a party ‘because tired’. As one supporter put it, because should be Word of the Year ‘because useful!’ (Flood 2014, The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/08/us-word-of-year-2013-because-dialect)

Actually, on the basis of corpus data from COCA and GloWbE,Footnote 7 we would suspect that the internet meme because science, also the name of a popular YouTube Channel founded in 2015, was first used around the year 2012 and is still the most common collocation in this construction.

In contrast to X-much and extrasentential not, however, modern because X may have first been geared towards a younger audience, but apparently it has never caught on in this age group in the same way. In our corpora at least, it has never been really popular on TV or in movies, but can be found quite often in internet language, on blogs, and also in news broadcasts and even in political debates. The reason for this is not quite clear, though. We suspect that teenagers and young adults in their conversational routines are maybe less concerned with reasoning, complex subordinate syntactic patterns, and subtle pragmatics (cf. Nippold et al. Reference Nippold, Frantz-Kaspar and Vigeland2017; Verhoeven et al. Reference Verhoeven, Aparici, Cahana-Amitay, van Hell, Kriz and Viguié-Simon2002). We thus would venture the hypothesis that the pragmatic effect of because X is probably too subtle to be interesting for a young usership that is primarily interested in syntactic fireworks to satisfy the need for extravagance and wittiness. This is also in line with what van den Stock et al. (Reference Van den Stock, Ghyselen, Lauwers, Speelman and Colleman2024) suspect, albeit only tentatively, with regard to the age-grading they find in innovative uses of two syntactic constructions in Dutch (the krijgen-passive and the weg-construction). While their older participants rate the conventional uses of the weg-construction higher and like the productive uses of the (more formal) krjjgen-passive better, ‘younger participants seem to be more drawn to the unconventional/imaginative/vivid nature of creative instantiations of the weg-pattern’ (Van den Stock et al. Reference Van den Stock, Ghyselen, Lauwers, Speelman and Colleman2024: 27). We believe this question warrants some further investigation in future research.

The fact that because X is still popular in online media, such as blogs, may have to do with the fact that materially written but conceptually spoken discourse (cf. Koch & Österreicher Reference Koch and Österreicher1985) often lacks efficient means to communicate subtle pragmatic messages like jokes, irony or sarcasm – one of the reasons for the introduction of the smiley in online discourse (‘I propose that the following character sequence for joke markers: :-) ’; Fahlmann 1982, www.cs.cmu.edu/~sef/Orig-Smiley.htm). Because X allows for the effective expression of subjective and intersubjective meanings even in materially written discourse. But it doesn’t make for great effects when used on TV shows.

6. On breaking rules

All three constructions discussed here thus deviate noticeably from standard syntactic patterns. Yet they still seem to follow certain basic principles of grammar (such as proximity of modifier and head). This is not Jabberwocky or Dada poetry. They also show remnants of their original semantic meaning, i.e. quantificational semantics in much, negation in not, and causal considerations with because. However, in contrast to their regular, grammatical counterparts, they are motivated by pragmatic considerations, as they carry extra pragmatic meaning. X-much can express special surprise or indignation (Racist much? Overreacting much? Hypocrisy much?). Extrasentential not emphasizes the negation and also expresses some sort of indignant or surprising, sarcastic speaker perspective, a pun played on the addressee: I liked the movie. Not. = ‘You think that I liked the movie, but I obviously didn’t.’ Because X offers a special (inter)subjective perspective, sometimes also in association with sarcasm or verbal aggression towards the addressee (because math, (duh)! = ‘This is so obvious you should have known this!’) or even third parties (because, you know, liability). In a word, the innovation and successful use of these novel constructions depends on what we described as a complex interplay of syntactic, semantic and pragmatic factors.

One central motivation for language users to (sometimes drastically) deviate from syntactic rules may be pragmatic, i.e. the conveying of subtle, non-semantic and speaker-oriented meaning. A second motivation is partly pragmatic, but also based on principles of communication and cognition. Language processing is usually an automated, subconscious process, aimed at communicative efficiency (see Hartsuiker & Moors Reference Hartsuiker, Moors and Schmid2017). But there may be various ‘tasks’ that need to be balanced. Keller (Reference Keller1994) lists eight maxims that form the basis for successful communication, which in turn is subject to the hypermaxim of linguistic interaction: ‘Talk in such a way that you are most likely to reach the goals that you set yourself in your communicative enterprise.’ These maxims include:

Maxim 1: Talk in such a way that you are understood.

Maxim 2: Talk in such a way that you are noticed.

Maxim 3: Talk in such a way that you are not recognizable as a member of the group.

Maxim 4: Talk in an amusing, funny, etc. way.

Maxim 5: Talk in an especially polite, flattering, charming, etc. way.

Maxim 6: Talk in such a way that you do not expend superfluous energy.

Maxim 7: Talk like the others talk.

Maxim 8: Talk in such a way that you are recognized as a member of the group.

As already mentioned above, the maxims of particular interest for the present article are the maxim of extravagance (Maxim 2), as Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1999) termed it, and the maxim of wittiness (Maxim 4), our term. Sometimes, in order to achieve their communicative goals, speakers need to express themselves in a particularly extravagant, i.e. noticeable, or a particularly witty, funny way. Note that the two are not necessarily interchangeable. You can be very extravagant, and noticeable, without being amusing or funny, for example by using obscene and inappropriate swear words. On the other hand, you can also be very amusing and funny without being particularly extravagant, for instance by using paradoxes: ‘I can resist everything but temptation’, as Oscar Wilde so famously put it. Or by telling jokes: ‘Did you hear about the two people who stole the calendar? They each got six months.’ And yet, both of these maxims may motivate syntactic innovation of the kind discussed here. While extravagance has received a considerable amount of attention in the literature (see, e.g., Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1999; Petré Reference Petré2017; Ungerer & Hartmann Reference Ungerer and Hartmann2020; Eitelmann & Haumann Reference Eitelmann and Haumann2022), Maxim 4, wittiness or funniness, has been mostly ignored. The data and ideas presented here, with a particular focus on verbal humor in TV shows and movies geared towards younger audiences, show that it probably deserves more attention in the future.

One way of being particularly noticeable or clever, or amusing and funny, is to be creative, to break with conventions, to deviate from what can be expected. This can be seen, for example, in the language of advertising and business where new and unusual terms attract attention. Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath1999) also discusses the maxim of extravagance (or ‘expressivity’) in the context of grammaticalization and suggests that speakers ‘sometimes … want their utterance to be imaginative and vivid – they want to be little “extravagant poets” in order to be noticed, at least occasionally’ (1999: 1057). Similarly, the three constructions discussed here also attract attention by deviating from expectations, and thus serve the maxim of extravagance and also, in some cases, the maxim of wittiness. They are not only noticeable, they can also be pretty funny and amusing. Extrasentential not probably sticks out in particular in terms of wittiness and fun, as can be seen in its distribution across media: it is a stock element of harmless comedy, as witnessed by Mike Myers’ interview. X-much initially took a similar path, but turned out to be more extravagant than funny or witty. It is a noticeable and extravagant expression of incredulity and reprisal: racist much?. Because X may be noticeable because of the syntactic violation, but it is probably less extravagant and less funny than the other two constructions discussed here. It thus also seems to be the one of the three constructions that can also be found quite often in mainstream news or political speeches, for example, rather than in TV comedy. And yet it seems to serve its purpose: it is noticeable (and gets copied at least by certain groups) and as such effectively gets its extra, pragmatic message across: subjective evaluation or verbal aggression.

Note that the constructions discussed here are usually context-dependent and also get support from intonation and facial expressions, which may also be stored as part of the conventionalized constructional information. Because X in particular, with its subtle differences in meaning often can only be disambiguated on the basis of audio-visual data from the speaker. Similarly, X-much can be interpreted as a simple question or an act of accusation. Here, the context and the reaction of the addressee become important to evaluate the actual speech act associated with that particular construction. What we do seem to witness, though, is a gradual development and diversification of these constructions. From simple interrogatives and negatives and causalities to reproaches, rebuttal and verbal aggression.

Nevertheless, for all three constructions discussed here we find that modern media such as TV, movies or the internet probably played a substantial role in their innovation and spread. The constructions served as markers of extravagance, wittiness, cleverness for their media characters and thus encouraged spreading and copying, first by early adopters, and then by the more general public. It seems like easier patterns such as extrasentential not fared a bit better in that respect, while X-much took a middle ground and because X remained somewhat rare with its rather delicate pragmatics (cf. Van den Stock et al. Reference Van den Stock, Ghyselen, Lauwers, Speelman and Colleman2024).

7. Summary and conclusion

This article has looked at the possible origin and use of three particularly noticeable, creative syntactic constructions in Present-day English: X-much, extrasentential not and because X. It was argued that these are special and closer to what Sampson called E-creativity than many other syntactic innovations. We hypothesized that their innovation must be part of deliberate linguistic behavior in adulthood, motivated by pragmatic factors on the one hand, and socio-communicative maxims such as extravagance and wittiness on the other. Their innovation and spread are first and foremost documented in the TV, movie and internet sections of the corpora investigated. We suspect that in this context they were deliberate innovations to attract attention or to create humorous effects, in particular for teenage and young adult audiences. In the case of extrasentential not we see a rather quick and easy adoption of the construction, probably due to its simplicity, noticeability, and strong pragmatic and socio-communicative effect. X-much also caught on, but remained to some extent a media phenomenon, partly because of its rather negative pragmatic associations. Finally, because X also found its way into general use, albeit with a different social group. It appears to be less common among teenagers now, but rather characterizes news broadcasts, political debates and blogs, where it not only conveys increased subjectivity, but may also serve as a marker of verbal aggression in the widest sense.

We identified two questions as potential topics for future research. First, the role of media language may warrant some further discussion. Given the lack of large corpora of natural, unscripted, informal, conversational spoken language this article could not actually show empirically that the constructions originated in the language of TV shows and movies. The data from our corpora certainly points in this general direction, but more data, and especially an empirical investigation of spoken language from the 1990s and early 2000s might be instructive. Second, in relation to media language, we hypothesized that the language use of teenagers and young adults may be different from that of older speakers in that younger speakers are more likely to use more creative, noticeable (deviant) linguistic structures. While this ‘adolescent peak’ (Van den Stock et al. Reference Van den Stock, Ghyselen, Lauwers, Speelman and Colleman2024: 27) is fairly well documented for lexical innovations (e.g. Palacios Martínez Reference Palacios Martínez and Ziegler2018), we still do not know about a lot about the links between age, extravagance and more complex constructions. The present study, like Van den Stock et al. (Reference Van den Stock, Ghyselen, Lauwers, Speelman and Colleman2024), brought some phenomena into the light that indicate some connex, but this will require further investigation.