1 Introduction

Honey, I shrunk the kids – the title of an American blockbuster film – left at least some speakers of English doubting: shouldn't it be shrank, or is shrunk also quite acceptable? Is shrunk perhaps a typically American form, or is it simply ‘wrong’? This small example raises several interesting questions: who determines what is ‘correct’ in English, have these norms changed over time, and do ‘normal’ speakers adhere to these norms? If they do not, what possible reasons are there?

In standard English today, we can observe two groups of verbs that on the one hand are very similar, yet on the other hand form their past tenses in a distinct way. The larger of these groups consists of the verbs cling, dig, fling, hang, sling, slink, spin, stick, sting, strike, string, swing, win and wring; they form their past tense and past participle identically by way of vowel change to <u> (i.e. sling – slung – slung; strike – struck – struck). Since Joan Bybee has worked extensively on the pattern of these verbs (e.g. Bybee Reference Bybee1995; Bybee & Moder Reference Bybee and Moder1983), I have called this group ‘Bybee verbs’ (with Joan Bybee's permission).

The second group is slightly smaller and consists of begin, drink, ring, shrink, sing, sink, spring, stink and swim. It is only in this second group of verbs that we can find interesting variation, and for this reason only this smaller group of verbs will be investigated in detail here. In standard English these nine verbs have past tense forms in <a> and past participles in <u>, resulting in three-part paradigms like sing – sang – sung or begin – began – begun where past tense and past participle are clearly distinct. However, even in standard English today we can observe some fluctuation between two different past tense forms, as the film title above indicates, and different dictionaries permit this fluctuation in different verbs, as table 1 shows.

Table 1. <u> – <a> variation in past tense verbs in a selection of dictionaries

* Note: in contrast to all other verbs, the OED does not give the past tense/past participle forms for stink as a paradigm (s.v. stink v.). The information on possible variability of this verb can therefore only be gleaned from the historical overview. 6–9 stands for 1600–1900, 8- for 1800 until now (or more precisely, the time of compilation). This might be an argument for a slight preference for stank, since it is explicitly marked as the current form, in contrast to stunk.

The OED, documenting (written) usage up to the end of the nineteenth century, has seven variable past tense forms; Collins English Dictionary, published roughly a century later and aimed at the domestic (British) market, lists four (three of which are identical to the OED), whereas the five large dictionaries specifically targeted at advanced learners (Cambridge, Collins, Longman, Macmillan, Oxford, all published in the first decade of the new millennium), have between four and no variable verbs (the four are stank/stunk, shrank/shrunk, sank/sunk and sprang/sprung). Most dictionaries do not comment on this variability; and the few regional labels that are used do not coincide. Thus Longman notes ‘AmE’ for three of these verbs (notably not stunk), Cambridge only notes stunk as a ‘US’ form, and Oxford only designates sprung as being ‘also NAmE’, but none of the other three verbs. Collins COBUILD does not cite any variation, which is particularly striking if we compare this to the earlier publication from the same publishing house from 1986. None of the dictionaries indicate on which basis the regional labels have been ascribed.

It is perhaps not surprising that in my investigation of British non-standard verb paradigms, this fluctuation also constitutes one of the most persistent patterns in the verb morphology of traditional British dialects (Anderwald Reference Anderwald2009). There are historical developments that can elucidate this variability diachronically, as section 3 details. A look at nineteenth-century grammars (with the help of the new resource of the Corpus of Nineteenth-Century Grammars (CNG)) in section 4 sheds light on the relatively recent historical process of standardization for these verb forms. A chronological analysis of these grammars shows that especially during that century, permitted variability is slowly reduced in favour of forms in <a>, at least for some verbs. However, the continuing present-day popularity of forms in <u> indicates that actual usage must have been quite resistant to prescriptive pressures, at least in these instances. The theoretical framework of Natural Morphology (Mayerthaler Reference Mayerthaler1981, Reference Mayerthaler, Dressler, Mayerthaler, Panagl and Wurzel1987, Reference Mayerthaler1988; Wurzel Reference Wurzel1984, Reference Wurzel, Dressler, Mayerthaler, Panagl and Wurzel1987) can help provide functional reasons for this persistence: past tense forms in <u> (i.e. past tense drunk, sung, swum) constitute ‘good’ past tense forms in the sense of Natural Morphology, and for this reason are able to withstand more artificial normative forces.

2 Past tense drunk, sung, rung, etc. in traditional British dialects

2.1 FRED

In order to investigate the use of <a> vs <u> forms of these verbs in traditional British dialect speakers, the Freiburg English Dialect Corpus (FRED) was employed. FRED consists of traditional dialect data by speakers mainly born before 1920 from across Great Britain. It was compiled with the aim of making possible – for the first time – quantitative comparisons across dialects. The corpus comprises over 2.4 million words (excluding interviewers’ utterances) from all the major British dialect regions.Footnote 1 It is clear, however, that even in a large corpus like FRED, not all medium-frequency verbs mentioned above will appear in sufficient quantities. For this reason, only the results for the more frequent begin, sing, drink, ring and sink are discussed in this section.

2.2 New Bybee verbs in FRED

For the investigation, all instances of past tense forms of the five verbs begin, sing, drink, ring and sink were collected from all dialect areas. They were classified as being standard or non-standard (began vs begun), and whether they had a singular or plural subject (I begun vs we begun). All instances of the participle (which is even rarer) as well as – some few – unclear instances are excluded in the following discussion. Some examples are provided in (1) to (5).

(1) We used to work long hours haying time, work at night till it begun to get dark, and that, and the hay begun to get dark with the dew. (FRED KEN 011) (Kent, South East)

(2) I heard a Gospel group singing. They sung The Rugged Cross, and they sung some more, more hymns. (FRED LAN 006) (Lancashire, North)

(3) He never drunk much. (FRED CON 001) (Cornwall, South West)

(4) I rung him up and told him. (FRED NTT 003) (Nottinghamshire, Midlands)

(5) Now the Ocean people had the selling rights of that pit see, and the Powell Duffryn sunk it see, that is what happened. (FRED GLA 002) (Glamorgan, Wales)

In contrast to many other verbs, which only appear rather sporadically in non-standard forms, these new Bybee verbs are highly frequent in their non-standard forms, as table 2 indicates.

Table 2. ‘New’ Bybee verbs in FRED

Ø = average

Figures from FRED show that these non-standard forms are on average used in over 40 per cent of all cases; this means that they are frequently the dominant option for these verbs for speakers of traditional British dialects. There are several possible reasons for this phenomenon. Traditional dialects are presumably quite conservative in nature, and the situation we find today could simply constitute the preservation of an earlier stage of the language. On the other hand, dialects have always been assumed to be relatively free from the pressures of standardization, and in this way they could be assumed to continue more ‘natural’ tendencies of the language and perhaps be more progressive than a fixed standard.

In order to determine the cause of the strong presence of <u> forms in these verbs, as a first step their history will be investigated.

3 History

3.1 Old English verb classes

Both verb groups mentioned above (i.e. cling, slink, win as well as drink, swim, sing) belonged to the Old English verb class IIIa (see also Esser Reference Esser1988; classification follows Krygier Reference Krygier1994). This verb class is characterized by the fact that its members had two quite different preterite stems, which seems to have been responsible for their different historical development as well as century-long variation: the preterite I stem (i.e. used for the first- and third-person singular past tense forms) was generally formed with <a>, whereas the preterite II stem (used for the second-person singular as well as the plural past tense forms which, in these verbs, is identical to the vowel found in the participle) was formed with <u>. A typical Old English paradigm for these verbs is exemplified by drink in (6).

(6) drincan – dranc, druncon – druncen

During Middle English, when inflectional endings were progressively lost, the difference between past tense singular and past tense plural forms became increasingly obscured and, probably as a consequence, past tense forms for these verbs became variable between <a> and <u>. In the North, typically the singular <a> stem was chosen as the past tense marker (Wyld coined the term ‘Northern preterite’ for this phenomenon; see Wyld Reference Wyld1927: 268), resulting in general past tense forms in <a> while the participle remained in <u>. Görlach also notes this kind of levelling as far north as Scots: ‘in some contrast to English, Scots almost invariably chose the former singular as the base form for the preterite – where there was a choice’ (Görlach Reference Görlach and Britton1996: 168–9). In western England, on the other hand, the ‘Western preterite’ used the plural stem vowel <u> to level the past tense paradigm (Wyld Reference Wyld1927: 268); according to Lass, ‘this begins to appear as a minority variant in the fourteenth century, and stabilizes for many verbs only in the period EB3 [i.e. 1640–1710] and later’ (Lass Reference Lass, Stein and Tieken-Boon van Ostade1994: 88).

Although Wyld claims that ‘the dialects of the S[ou]th and Midlands preserve, on the whole, the distinction between the Singular and Plural of the Pret[erite], where this existed in O.E., with fair completeness during the whole M.E. and into the Modern Period’ (Wyld Reference Wyld1927: 268–9), both patterns seem to have spread geographically across the country, and were either dominant in different verbs, or indeed in direct competition. With standardization and concomitant codification of verb paradigms from Early Modern English onwards, the former coherent verb class IIIa was thus essentially split between those verbs displaying the Western preterite (e.g. string – strung – strung), today the majority pattern (our ‘Bybee verbs’), and those following the Northern preterite pattern, resulting in a three-part paradigm today (drink – drank – drunk).

Considering this long-standing variation, it is perhaps not surprising to find that even today in non-standard dialects, these three-part verbs (e.g. StE drink – drank – drunk) show a very strong trend towards merging with two-part verbs, replacing the StE past tense drank with drunk, as we have seen in data from FRED. This results in a partially levelled paradigm drink – drunk – drunk, as also noted by Bybee (e.g. Bybee Reference Bybee1995; Bybee & Moder Reference Bybee and Moder1983). Historical continuity in this sense is certainly a first factor that plays a role in the persistence of these verb forms.

3.2 Singular vs plural

Since variation between forms in <a> and forms in <u> was originally determined by number, it is conceivable that reflexes of this old constraint could still be observed today. In order to test this possibility, all occurrences of past tense begun, drunk, sung, sunk and rung in FRED were coded for their subject number. Results are displayed in table 3.

Table 3. Singular and plural subjects of new Bybee verbs; figures are percentages for each spelling

As the figures indicate, only drank vs drunk and began vs begun behave in the expected way: drank has a higher percentage of singular referents than drunk, as might be expected from the Old English distinction, while the difference between began and begun is much smaller. For all other verbs, this trend is skewed in exactly the opposite direction. This opposite trend is strongest for sing, but is also quite noticeable for ring and sink. Despite appearances, however, none of these differences are statistically significant.Footnote 2 Whether the subject of a past tense form is in the singular or the plural, then, clearly does not determine today whether the form of the verb takes <a> or <u> for the past tense. This old distinction seems to have given way to truly levelled forms in the dialects today.

3.3 Past tense drunk etc. in historical sources

3.3.1 Past tense drunk etc. in historical corpora

Lass (Reference Lass, Stein and Tieken-Boon van Ostade1994) has investigated the diachronic development of some of our verbs on the basis of the Helsinki Corpus of English (HC, see Kytö Reference Kytö1991). As Lass has noted, for some verbs variation must have continued beyond Early Modern times (the last period included in the HC). From the established literature, it is not quite clear when this variation ended in written English, but it is quite striking that in written sources, variation after Early Modern English is extremely difficult to trace. As lexical verbs with quite specific semantics these verbs span frequency bands from the medium-frequent (drink, begin) to the quite rare (slink, spring), and for this reason are only relatively rarely encountered in their past tense forms in the historical corpora available to date. As an example, even for drink, one of the more frequent of these verbs, in the Helsinki Corpus there is only a single instance of a past tense form in <u>, drunk, outside Old English; in ARCHER 1 (Biber, Finegan & Atkinson Reference Biber, Finegan, Atkinson, Fries, Tottie and Schneider1994), we also find only one example, namely from the period 1700–50 (as opposed to 41 instances of drank).

The situation is a little different for sink. Here we can observe a switch-over pattern where sunk appears as the regular form until the beginning of the nineteenth century; sank then takes over and seems to become obligatory in its turn. In all cases, however, these claims are based on very low absolute figures and can therefore be pointers in one direction at best.

For sing, both sang and sung were still noted as the regular past tense forms by the OED (at the end of the nineteenth century). However, absolute figures for sing are so low that a diachronic comparison in the material that is available to date is unrevealing, and the situation is largely similar for ring.

From the historical corpus material available we cannot really deduce whether standardization had already set in for these verb forms, and if so, in which direction standardization proceeded for the individual verbs; or whether the written sources simply mask variability in spoken usage. For this reason, it might be revealing to investigate changing attitudes (if any) in prescriptive sources of the time. Since the little material there is indicates that interesting things were happening, or were continuing to happen, in the nineteenth century, I have investigated how nineteenth-century grammars dealt with this problematic area of variability in grammar.

This investigation in no way implies that ordinary dialect speakers were influenced directly by the attempts of grammarians to standardize these verb forms. In fact, as the persistence of extreme variability shows, ordinary speakers up to today are clearly not influenced by prescriptive norms in the area of past tense verbs (in fact some dialectologists, like Peter Trudgill (p.c. 25 June 2010), argue that prescription has no effect on spoken language whatsoever). On the other hand, it is only in a very small subclass of these verbs (a maximum of five, as the overview in section 1 has shown) that today the self-proclaimed authorities (authors of grammar books and – mostly anonymous – dictionary compilers) do not agree on one verb form as ‘correct’. It is striking, then, that we should find almost complete agreement among prescriptivists on the ‘correct’ paradigms for most of these verbs today, as well as very little variation in the written language, but massive variation in the spoken language. We have basically answered the question where this variability in the spoken language comes from historically. We will now take the complementary perspective and ask, where does the widespread agreement in prescriptive sources (and, perhaps following from this, in written sources) come from, and how has it evolved over time? In other words, what the next paragraphs investigate is the abstract process of standardization itself, made concrete by exemplifying it with (a selected number of) irregular verbs. This is not to imply that spoken language changed with these prescriptions – indeed my main point is that ordinary language use has been, and probably still is, quite immune to these pressures from standardization, and I will support my argument with functional reasons.

3.3.2 The Corpus of Nineteenth-Century Grammars (CNG)

The Corpus of Nineteenth-Century Grammars (CNG) at the time of writing consisted of 70 grammar books published during the nineteenth century written for school or home use; 40 were published in Great Britain, 30 in the United States. They span the usual range from school grammars to more scholarly works that can already be found for eighteenth-century grammars (see in particular contributions in Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade2008), and in many cases these grammars continue traditions already established a century before.Footnote 3 In order to compile an electronically readable corpus, the internet was searched for all full-text grammar books from the nineteenth century. (This search is repeated periodically, and the CNG has been growing in fits and starts as a result.) As most grammar books (then as now) contain a list of irregular verbs, the results can be quite easily compared across grammars. Possible variation can then be correlated with the publication dates.Footnote 4 Since British grammars were widely in circulation also in the US, we are probably justified in considering them together to get a first overview of diachronic developments in this area of prescriptive grammar writing. In a second step, it is also possible to trace developments for British and American grammars separately. Since one of the suspicions was that shrunk might be a peculiarly American form, we shall follow up this suggestion in the next section. In order to put nineteenth-century grammars in context, some grammars from the end of the eighteenth century were added. In particular, these are Murray's influential English grammar, but also Priestley's grammar of the same title. In this way, it becomes clear where nineteenth-century grammarians continue a tradition of grammar writing, and where they depart from it. The inclusion of these earlier grammars is also justified by the fact that they continued to be read (and printed) widely; in fact they were republished regularly well into the first half of the nineteenth century, or even beyond. Besides, many nineteenth-century grammar writers took Murray as a model and either followed him unquestioningly, or discussed him critically. In both cases, including these important sources seems justified. These eighteenth-century grammars are however not included in the overview count given above.

3.3.3 New Bybee verbs in the CNG

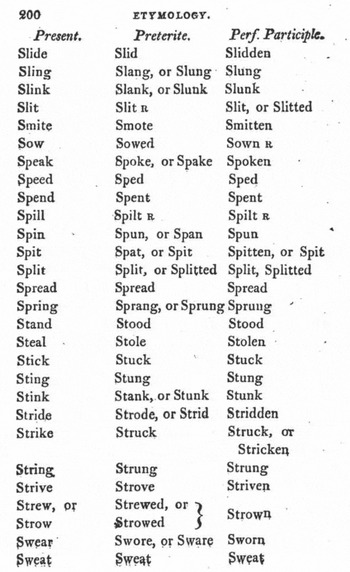

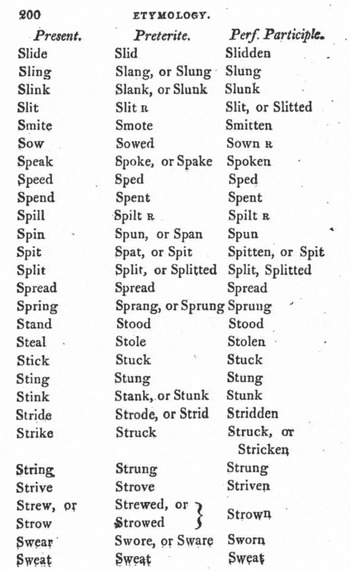

Before we begin a detailed investigation of individual variable verbs, it is worth mentioning that most grammars concur on a large number of verbs and do not record any, or hardly any, disagreement. Of the 23 verbs under investigation, only 11 show notable variation.Footnote 5 These are the verbs ring, shrink, sing, sink, sling, slink, spin, spring, stink, swing and swim. If we compare comments on these verbs, they fall into several groups. In order to understand the following diagrams, a few words on the procedure are in order. The full text versions of the grammars were manually searched for the almost obligatory overview tables of irregular verbs. A typical example (one page of eleven) is given in figure 1.

Figure 1. Typical table of irregular verb paradigms, Crombie 1809

The paradigms for the 23 verbs under investigation were copied to a spreadsheet and underwent further manipulation. All additional comments and footnotes were also copied. The paradigms were then coded for whether a past tense form in <a> or in <u> was prescribed or, indeed, if both forms were allowed. For reasons of pure convenience, numerical codes were chosen. In particular, <a>-forms were coded as ‘1’, variable forms as ‘2’, and <u>-forms as ‘3’, although any other numbers would have served the same purposes. A linear regression was computed in each case and is added as a straight line in the diagrams. The question whether regular forms (i.e. in <ed>) are also allowed or recommended will not be discussed here. In the comparison of the following diagrams it is important to remember that the x-axis is a temporal axis. Several grammars published in the same year proclaiming the same verdict will therefore appear as overlaying marks on top of each other. Any other arrangement would have seriously distorted the time line, since – as will become readily apparent – grammars cluster around certain publication dates and this clustering is in this way preserved in the diagrams.

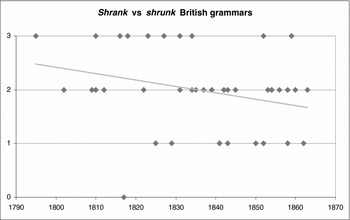

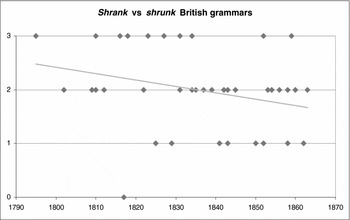

Of all these verbs, the verb shrink seems to have undergone the most striking development. Figure 2 clearly shows that the past tense form shrunk is noted throughout the century, but is particularly frequent in grammar books until c. 1838. Variable forms are also mentioned throughout the century but become more numerous after 1830, virtually taking over from forms in <u>. Forms in <a> are only found after 1825 or so and continue into the second half of the nineteenth century, although they are not nearly as frequent as variable forms. The impression of a diachronic change in prescriptive pronouncements is supported by the regression line: it slopes to a point beneath the ‘2’ line, indicating this striking shift in verdicts from shrunk to shrank.

Figure 2. Past tense of shrink in the CNG

As one can see in figure 3, this pattern is essentially caused by the British grammars contained in the CNG. If we subdivide grammars into British and American ones, the pattern for the British grammars remains essentially the same as the overall picture in figure 2. We can therefore say that British grammars are largely responsible for the pattern in figure 2. American grammars, on the other hand, do not in a single case prescribe shrank as the only permissible form, as shown in figure 4. What we can observe, however, is that from 1830 onwards variable forms become acceptable. Whereas in British grammars we have a switch-over pattern from forms in <u> to forms in <a> as the solely acceptable past tense forms, in American grammars this prescriptive change is much milder and only extends to an increasing permissibility of variation. In other words, past tense forms in <a> become more acceptable over the course of the nineteenth century in American grammars, but – in contrast to British grammars – are never cited as the only correct forms.

Figure 3. Past tense of shrink in British grammars in the CNG

Figure 4. Past tense of shrink in American grammars in the CNG

In a way similar to shrink, but with a development that is not quite so pronounced, we find the verbs swing, sling, slink – all verbs where present-day grammars agree that they form their past tense with <u>. During the nineteenth century, grammarians still varied in their pronouncements, and overall we can even observe a trend away from <u>, towards allowing variable forms. Exemplarily this is illustrated for the verb swing. However, it is also notable that the trend is much weaker than for shrink. Swung clearly remains the majority option in grammar books throughout the nineteenth century (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Past tense forms of swing in the CNG

If we compare British and American sources, we see striking differences again (figures 6 and 7). Whereas some grammarians prescribe forms in <a>, and some allow both forms in <a> and in <u>, American grammarians are unanimous in allowing only swung. Again, this picture is basically the same for sling. Slink patterns much like shrink above, in that in American grammars we can observe a switch around the middle of the century towards variable forms.

Figure 6. Past tense forms of swing in British grammars in the CNG

Figure 7. Past tense forms of swing in American grammars in the CNG

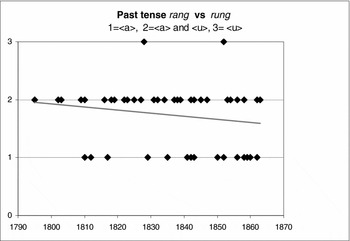

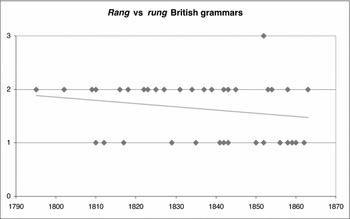

Quite in contrast to the data on shrink, the four verbs ring, swim, sing and spring never, or almost never, appear in these nineteenth-century grammars with past tense forms in only <u>. Instead, past tense forms are cited as variable at the beginning of the century, and are increasingly prescribed as forms in <a> from c. 1810 onwards, though many grammarians continue to give variable forms, as figure 8 demonstrates exemplarily for rang vs rung. The chronological development is so similar for swim, sing and spring, although grammars do not always treat all four verbs identically, that further lexeme-specific diagrams can be dispensed with here. In all cases, the linear regression clearly indicates the trend away from variation, towards forms in <a>.

Figure 8. Past tense of ring in the CNG

Strikingly, in all four lexemes this development again mirrors the development in British grammars only (figure 9). In contrast, in all four cases, American grammars uniformly allow variable past tense forms (coded by ‘2’; figure 10). Neither <a>-forms nor <u>-forms alone are prescribed in more than one case. The standardizing trend away from variation can therefore be attested for British grammars only.

Figure 9. Past tense of ring in British grammars in the CNG

Figure 10. Past tense of ring in American grammars in the CNG

Interestingly, it is with these forms that the preference for <a> is rationalized at least occasionally, and reasons are given why past tense forms in <a> should be preferred. Thus at the beginning of the century Crombie advises: ‘Respecting the preterites which have a or u, as slang, or slung, sank or sunk, it would be better, were the former only to be used, as the Preterite and Participle would thus be discriminated’ (Crombie 1809: 199). In very similar terms, Pinnock twenty years later reiterates: ‘When the past tense has a or u, as in sang or sung, sprang or sprung, sank or sunk, span or spun, it is preferable to use the a only as the imperfect, that it may be more readily distinguished from the perfect participle’ (Pinnock 1829: 161). I will come back to these purported reasons in section 4 below.

In a third group of verbs, we can observe only minimal chronological development over the nineteenth century. The verbs sink, sling and spin show no clear diachronic trend in nineteenth-century grammars. Throughout the century, grammars agree on variable forms being acceptable, or prescribe the past tense in <u>. Only rather sporadically are forms in <a> prescribed. Overall, therefore, the regression line is almost level, indicating that variable forms are still favoured over the other options towards the end of the century. This is all the more striking as the past tense of slink and spin is today always found with <u>, whereas the past tense of sink is generally formed with <a>, although some variability is acknowledged.Footnote 6 These three verbs are by no means a homogeneous group today, but the development that has led to the present situation must have set in later than the nineteenth century, or at least after the period covered by the CNG at present, i.e. after 1870.

In most of the other verbs, however, we can clearly see a development towards less variation; in a significant number of cases, the conflict around variable forms, permitted throughout the nineteenth century, is resolved in favour of forms in <a> towards the end of the century. British sources seem to be more prescriptive, and rationalize their preference of forms in <a> with quasi-functional arguments (i.e. supporting the distinctiveness of simple past and past participle forms). American grammars as a whole favour forms in <u> more widely, and often allow both forms in <a> and in <u> without expressing preferences.

As mentioned above, it remains to be investigated what the actual historical development in past tense forms in spoken language was. At the present moment, it is impossible to tell whether this difference in the grammars relates to real-world differences between the two countries, and it is too early to say which of the two countries, and the two national systems, was more progressive, which was more conservative than the other.

4 Norm constitution

The subject of norm constitution in Britain especially over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries will still have to be dealt with in detail – as the Milroys note, ‘[prescription] has not been fully studied as an important sociolinguistic phenomenon’ (Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999),Footnote 7 but for a start it has to be noted here that the situation in Britain was clearly quite different from other European countries. On the one hand, despite intensive lobbying by writers like Jonathan Swift in the early eighteenth century, the British government never founded a language academy – much in contrast to a country like France and its Académie française (nor is there an American equivalent). For English, therefore, there is no officially endorsed highest authority on language that would prescribe explicit norms. Much in contrast to Germany, which also does not have a language academy, Britain does not have a ‘self-appointed’ highest guardian of the language either. In Germany, the Duden publishing house has long taken on this function and has prescribed ‘correct’ pronunciation and orthography as well as grammar, starting in 1880 with the first publication of an orthographic dictionary implementing the new Prussian school orthography (set by the Prussian minister for schools in a conference in 1874). To this day, the Duden is the acknowledged authority on doubtful questions of language use.Footnote 8 No such self-proclaimed institution exists in Britain, perhaps with the exception of Fowler's Modern English Usage (first published 1926). Nevertheless, by all measures that are usually employed ‘standard English’ clearly does exist: apart from a wealth of publications dealing with the standard (dictionaries, self-help books, grammars aimed at native speakers), we can observe the existence of strong norms in speakers’ intuitions of what constitutes ‘good’, ‘proper’ or ‘correct’ English, and the investigation of past tense forms above can show us how these norms came into existence and were solidified over the course of the nineteenth century.

As the Milroys point out, ‘the process of language standardisation involves the suppression of optional variability in language’ (Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999: 6, original emphasis). This is probably only one of several more general principles we can observe during the process of standardization (for more details, cf. the principles enumerated by Stein Reference Stein, Cheshire and Stein1998, also loosely based on Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999), but it is one principle that is clearly observable in the treatment of at least some variable verb forms by nineteenth-century grammars under investigation here. As we have seen, in many cases, the regression line slopes downward, away from variation. With the help of simple statistical techniques, we have been able to make this process of standardization visible. In these cases, the trend clearly goes towards past tense forms in <a>, setting up three-part paradigms that make past tense and past participle as different from each other as possible.

It is quite likely that the underlying model here was Latin, which has distinct past tense and past participle forms. This development would be in line with Stein's principle 2a: ‘(2) external principles determin[ing] the banning of types of forms NOT accepted into W[ritten] S[tandard] . . . may be of two basic types: (a) an ideology of language based on presumed Latin models and its “logic” . . . (b) factors derived from the ideology of essayist literacy’ (Stein Reference Stein, Cheshire and Stein1998: 38). In this sense we can say that nineteenth-century grammarians’ choice of drink – drank – drunk over drink – drunk – drunk is ideologically (rather than functionally) motivated – this ideology need not be made explicit, but can be transported through the medium of second-rate grammar books, where authors tended to copy from each other profusely without acknowledgement (see Görlach Reference Görlach1998; Rodríguez-Gil & Yáñez-Bouza forthcoming). In this manner, an implicitly agreed dictum can make it into schools, academies and private tutoring, evolving into ‘polite usage’ or ‘received wisdom’ from there.

5 Present-day persistence

Despite clear norms today (anyone can look up a verb in a dictionary and find out the ‘correct’ past tense form), we have seen that at least for traditional dialect speakers, variation persists. For younger urban speakers, we can compare figures from FRED presented in section 2.2 above with more recent data from COLT, the Corpus of London Teenage Speech. COLT was compiled in 1993 by a research team from Bergen, Norway, and records everyday spontaneous speech of teenagers from various London boroughs and Hertfordshire. Speakers are divided into three social groups, higher, middle and lower (for details, see Stenström, Andersen & Hasund Reference Anna-Brita, Andersen and Kristine Hasund2002: 20).

In data from COLT, the new Bybee verbs also occur, but comparatively infrequently. (COLT contains only roughly half a million words, whereas FRED is almost five times as large.) For this reason, it does not make much sense to look at the verbs individually; in almost all cases, occurrences are below five in the subcategories, and only five verbs occur in the past tense at all (in either the standard or the non-standard form); these are begin, drink, ring, stink and sing. When we add all five verbs, however, the social patterning for the new Bybee verbs becomes nicely apparent, as table 4 shows.

Table 4. ‘New’ Bybee verbs in COLT

While the average of 36.7 per cent seems considerably lower than the relative frequency for the Bybee verbs in FRED, this average clearly masks social differences. All FRED informants belong to the lower social groups and should thus be compared only to social group 3 in COLT. Indeed, frequencies for the lower social group (group 3) of 66.7 per cent look very similar to the data from FRED, and in fact the difference is not statistically significant.Footnote 9

In the data from COLT we can also clearly see that although this non-standard feature is sharply stratified, the break point is not between social groups 2 and 3, as for many non-standard features, but between the highest social group, where we find non-standard Bybee verbs at a very low rate, and social group 2, where non-standard Bybee verbs are also extremely frequent at around 40 per cent. In other words, we can see that non-standard Bybee verbs are still a very prominent feature of non-standard speech today, and that they seem to have gained social ground, having become a frequent feature also of middle-class speech (at least in the restricted sample of London teenagers in the 1990s). Bybee verbs thus do not seem to have lost any of their attraction for other verbs; quite the opposite, apart from historically, they also seem to be spreading socially today. The question remains, why?

6 Functional explanation

6.1 Language-internal naturalness

Wolfgang Wurzel (Reference Wurzel1984, Reference Wurzel, Dressler, Mayerthaler, Panagl and Wurzel1987, Reference Wurzel, Dressler, Luschützky, Pfeiffer and Rennison1990a, Reference Wurzel, Boretzky, Enninger and Stolzb, Reference Wurzel and Lahiri2000) has developed a systematic account of inflectional systems that allows the analyst to compare linguistic forms in one language and to determine which of two (or more) forms can be said to be more ‘natural’ than the other. In order to do so, Wurzel claims that every inflectional system of a language can be characterized along the following parameters:

(a) the inventory of category structures and categories (e.g. number: singular, plural, dual; case: nominative, genitive, accusative, dative, instrumental, vocative, etc.)

(b) base form vs stem inflection (cf. English friend – friends vs Latin amic-us – amic-i)

(c) separate or combined symbolization of categories (cf. Swedish kapten-er-s ‘captain’+plural+genitive vs Russian kapitan-ov ‘captain’+genitive plural)

(d) number (and manner) of formal distinctions in the paradigm (Old High German NSg = ASg ≠ GSg ≠ DSg)

(e) types of markers involved (e.g. affixes vs ablaut)

(f) existence of inflectional classes (German: yes, Turkish: no)

An inventory of the inflectional system along these parameters determines the characteristic (‘system-defining’) structural properties which are dominant in the system. Inflectional classes that conform to these properties constitute dominant classes, which is reflected in their type frequency. Individual words can then be analysed as being more or less ‘natural’ or ‘normal’ with respect to these dominant features when we determine whether they conform to these features or not. Wurzel claims that inflectional classes (in those languages that have them) are cognitively real; they are functionally motivated since they aid the language user's task of storing and retrieving linguistic forms. The existence of these inflectional classes can be observed in particular during the incorporation of loanwords, or more generally during periods of language change.

6.2 Present-day verb classes

Although Wurzel has mainly worked on German noun classes, we can quite easily extend his framework to English verbs. Along his six parameters, present-day English verbs can be characterized by the fact that present and past tenses are expressed morphologically; a range of other tenses are expressed periphrastically with the help of the infinitive (i.e. the future) or the past participle (the range of perfect constructions).Footnote 10 Most English verbs are regular, forming the past tense and the past participle with the suffix -ed, but a sizeable number of verbsFootnote 11 have remained strong or indeed become irregular through a number of phonological changes, amongst other things also employing ablaut or vowel change to indicate tense. Formal distinctions in the irregular verbs range from three (all forms are distinct) to one (all forms are the same). It has to be noted that, as is usual in these cases, a low type frequency (of around 160 irregular verbs, as opposed to several thousands of regular verbs) goes hand in hand with a very high token frequency – although text counts vary, English irregular verbs today make up between 70 and 75 per cent of verbal tokens in running text, especially in spontaneous spoken discourse (see e.g. Dahl Reference Dahl2004: 300–1; Pinker Reference Pinker1999: 227).

While the regular verbs form one large verbal class that cannot be distinguished further, the present-day English irregular verbs can be grouped into five classes on the basis of the three ‘principal forms’, i.e. infinitive, past tense, and past participle (abbreviated present, past and past participle here respectively). If one considers quite abstractly whether these three forms are identical or non-identical for each given verb, five logical possibilities obtain, all of which are in fact attested in English:

Class 1 present ≠ past ≠ past participle (e.g. drink – drank – drunk)

Class 2 present ≠ past = past participle (e.g. cling – clung – clung)

Class 3 present = past participle ≠ past (e.g. come – came – come)

Class 4 present = past ≠ past participle (e.g. beat – beat – beaten)

Class 5 present = past = past participle (e.g. hit – hit – hit)

As also all regular verbs follow the abstract pattern of class 2 (present ≠ past = past participle), it is clear already intuitively that this pattern constitutes the dominant pattern for verbs, and in fact the majority of irregular verbs belong to this verb class. Clearly, an English verb following the pattern present ≠ past ≠ past participle with three distinct forms is less ‘natural’ in this technical sense than a verb following the dominant pattern present ≠ past = past participle.

This claim might at first glance seem counterintuitive. Surely the more distinctions, the better? And indeed Mayerthaler (Reference Mayerthaler, Dressler, Mayerthaler, Panagl and Wurzel1987: 49) for one would argue that very generally, a separate symbolization of discrete categories should always constitute a more natural system cross-linguistically (following the well-known ideal of uniformity, or biuniqueness: one function – one form). However, we can easily show that for English verbs, this claim cannot be supported.Footnote 12 Consider the fact that practically every new verb that enters the language joins the class of regular verbs. This makes the class of regular verbs potentially infinite. Even if we do not take into consideration all potentially new verbs, it can easily be calculated that the group of regular verbs that already exist exceeds the group of all irregular verbs by a factor of at least 30:1 at a conservative estimate. Several thousands of regular verbs, in other words, are used by speakers and understood by hearers, although they do not make a formal distinction between past tense and past participle. This is already a very strong indication that a formal distinction into three forms is not cognitively necessary for speakers of English.

Even if we only consider the type frequencies of irregular verbs, verb class 2 dominates. Of 167 irregular verbs in my count (see Anderwald Reference Anderwald2009: 198–204 for a detailed breakdown), 81 verbs (or 48 per cent) belong to verb class 2, 59 verbs (or 35 per cent) belong to verb class 1. Whichever way we count, then, we arrive at verb class 2 as the largest, and therefore the most natural, class of verbs – for Present-day English. This does not imply that any lack of formal distinctions makes a verb class more natural (clearly class 5 is not a dominant class). It only implies that the 3-way distinction found only in class 1 is not essential to communication. And indeed, the verbal categories expressed with the help of the past participle are periphrastic in all cases, so that a redundant marking (by the auxiliary and morphologically on the verb) is not essential for understanding. Thus, the perfect is obligatorily marked by a form of have, the passive by a form of be today. (Consider I found vs I have found, he was found or he said vs he had said, it was said – see Anderwald Reference Anderwald2009: chapter 1 for a fuller discussion.) What seems to be cognitively important, and what is preserved by most irregular as well as by all regular verbs, is the morphological distinction of past vs non-past. Again, this makes cognitive sense, as the (simple) present and past tenses in English are the only tenses that are formed purely morphologically (I find – I found, we say – we said).

6.3 Analysing Bybee verbs

With the apparatus in hand provided by Wurzel, we can now proceed to analyse the robust persistence of non-standard Bybee verbs, despite pressure from openly prescriptive or implicit norms. A large subclass of fourteen class 2 verbs, namely the group of Bybee verbs like cling – clung – clung, are ordered around the prototypical past tense form strung, as Bybee and co-authors have shown (see Bybee & Slobin Reference Bybee, Slobin and Ahlqvist1982; Bybee & Moder Reference Bybee and Moder1983; Bybee Reference Bybee1985, Reference Bybee1995), forming their past tense as well as their past participle with <u>, prototypically pronounced /ʌ/ in the south of England and /ʊ/ in the north.Footnote 13 The complete template for the past tense forms is given in (7):Footnote 14

(7) [C (C) (C) ʌ velar/nasal]past

This template can be regarded as a marker of this verbal subclass in Wurzel's sense. As this marker is extra-morphologically motivated (namely through its phonological shape), the marker is stable, conferring its stability on the verbal (sub)class. The class of Bybee verbs is thus stable through having this stable marker, in addition to following the dominant pattern present ≠ past = past participle.

6.4 Historical attractor

These Bybee verbs have attracted a number of different verbs historically; of the list in section 1, six verbs either did not exist in Old English or were conjugated differently: dig, fling, hang, stick, strike and string. Strike, for example, was an Old English class I verb which switched verb classes during Middle English; dig, fling and string only entered the English language in Middle English times and became irregular – unusual for loanwords; hang goes back – among other things – to an Old English weak verb that became strong between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, and stick was also an Old English weak verb (for individual histories see the OED s.vv. dig, fling, hang, stick, strike, string). These Bybee verbs thus acted as a powerful attractor already in earlier times.

6.5 Current attractor

The stable subclass of Bybee verbs, as we have seen, even now still acts as an attractor for the slightly smaller subclass of nine class 1 verbs around drink, which have fluctuated historically between past tense forms in <a> and <u>. By joining the verbs around strung, these nine new Bybee verbs become more natural in Wurzel's sense: their overall pattern conforms to the system-defining property present ≠ past = past participle in not distinguishing past tense and past participle forms, and in addition the stable marker [C (C) (C) ʌ velar/nasal]past spreads to more verbs (23 instead of 14), in turn further increasing the stability of this sub-class of verbs. It should therefore not be surprising if other verbs followed suit, and indeed this is what we observe with non-standard past tense forms like run and come, which also follow this pattern. The only new irregular verbs that are forming today, i.e. non-standard forms like drug or snuck (instead of standard English dragged or sneaked) that can be observed in American English, also conform to this pattern (see Hogg Reference Hogg, Nixon and Honey1988; Murray Reference Murray1998).

7 Conclusion

We have seen that traditional dialect speakers as well as urban vernacular speakers of British English tend to prefer past tense forms like drunk, sung over the standard drank, sang. The analysis has shown that the existence of these alternative (non-standard) forms can be traced back historically to Old English. However, this historical continuity alone does not explain their continuing success. Instead, their enormous stability seems to be due to the fact that they can be functionally motivated. In the sense of Wurzel (Reference Wurzel1984, Reference Wurzel, Dressler, Mayerthaler, Panagl and Wurzel1987), they are more ‘natural’ than their standard English counterparts drank, sang, since they conform to the system-defining structural properties of English, thus easing the cognitive load of the language learner (and language user). The question therefore is not why speakers tend to use drink – drunk – drunk rather than drink – drank – drunk, but what motivated grammarians to prescribe distinct forms for past tense and past participle in the standard for these verbs? As our analysis of nineteenth-century grammars has shown, variation in these verbal forms as such is eradicated over this period, in line with the Milroys’ and Stein's principle of ‘no variation’ (Milroy & Milroy Reference Milroy and Milroy1999; Stein Reference Stein, Cheshire and Stein1998).Footnote 15 In addition, Latin as the implicit model and the paragon of logic can be traced in some grammarians’ explicit comments on the preferability of distinct past tense and past participle forms, although this distinction is functionally redundant (and is indeed an instance of what Dahl calls ‘dumb’ redundancy; see Dahl Reference Dahl2004).

Answering the questions from the beginning, we have seen that a general consensus exists about what constitutes ‘correct’ past tense forms in English, at least parts of which can be shown to have evolved over the course of the nineteenth century. These norms do indeed change over time, as an investigation of nineteenth-century grammars has illustrated. Speakers, however, do not necessarily follow these explicit norms, as the corpus analysis has demonstrated. At least some non-standard forms like past tense drunk or sung that are highly frequent can be functionally motivated, which may explain their robustness in the face of strong norms.

Appendix: list of all historical grammars included in this study

Titles have been shortened. Years in brackets give the first edition or, where not available, the earliest edition known. For additional details see Görlach (Reference Görlach1998) and Rodríguez-Gil & Yáñez-Bouza (ECEG) (forthcoming).

Anonymous. 1863. An English grammar for the use of schools. Dublin: Alexander Thom.

Adams, Charles. 1838. A system of English grammar. Boston: D. S. King.

Allen, Alexander & Cornwell, James. 1841. A new English grammar. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Andrew, James. 1817. Institutes of grammar. London: Black, Parbury & Allen.

Arnold, Thomas Kerchever. 1853. Henry's English grammar. London: Rivingtons.

Bain, Alexander. 1863. An English grammar. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green.

Bartle, George W. 1858. An epitome of English grammar. London/Liverpool: Piper, Stephenson & Spence/Edward Howell.

Booth, David. 1837. The principles of English grammar. London: Charles Knight & Co.

Brown, Goold. 1857 [1823]. The institutes of English grammar. New York: Samuel S. & William Wood.

Bullions, Peter. 1851 [1834]. The principles of English grammar. New York: Pratt.

Cardell, William S. 1827. Philosophic grammar of the English language. Philadelphia: Uriah Hunt.

Clark, William. 1835. English grammar, systematically arranged. Wisbech: N. Walker.

Cobbett, William. 1819 [1818]. A grammar of the English language. London: Thomas Dolby.

Coghlan, John. 1868. A critique and textual outline of English grammar. Edinburgh: William P. Nimmo.

Comly, John. 1834 [1803]. English grammar, made easy to the teacher and pupil. Kimber & Sharpless.

Cramp, William. 1838. The philosophy of language. London: Relfe & Fletcher.

Crombie, Alexander. 1809. A treatise on the etymology and syntax of the English language. London: J. Johnson.

Currey, George. 1856. An English grammar, for the use of schools. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Davidson, J. Best. 1839. The difficulties of English grammar and punctuation removed. London.

Del Mar, Emanuel. 1842. Grammar of the English. London: Cradock & Co.

Doherty, Hugh. 1841. An introduction to English grammar. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Ellison, Seacome. 1854. A grammar of the English language for the use of schools and students. London: Nathaniel Cooke.

Fearn, John. 1827. Anti-Tooke; or an analysis of the principles and structure of language, exemplified in the English tongue. London: Longman etc.

Fisk, Allen. 1822 [1821]. Murray's English grammar simplified. New York: Clark.

Fowle, William Bentley. 1842. The common school grammar. Boston: W. B. Fowle & Nahum Capen.

Fowler, William C. 1855 [1850]. English grammar. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Frost, John1832 [1828]. Elements of English grammar with progressive exercises in parsing. Boston: Carter, Hendee & Co.

Gilchrist, James. 1816. Philosophical etymology, or rational grammar. London: Rowland Hunter.

Graham, George F. 1862. English grammar practice. London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts.

Greene, Roscoe G. 1830 [1829]. A practical grammar of the English language. Portland: Shirley & Hyde.

Greene, Samuel S. 1863 [1856]. An introduction to the study of English grammar. Philadelphia: H. Cowperthwait & Co.

Greenleaf, Jeremiah. 1824 [1819]. Grammar simplified, or an ocular analysis of the English language. New York: Charles Starr.

Guy, Joseph. 1829. Guy's new exercises in English syntax. London: Baldwin & Cradock.

Hamlin, Lorenzo F. 1832 [1831]. English grammar in lectures. Brattleboro: Peck, Steen & Co.

Harrison, Ralph. 1812 [1787]. Rudiments of English grammar. Philadelphia: John Bioren.

Harvey, Reuben. 1851. A common sense grammar of the English language. Dublin: I. & E. Mac Donnell.

Hiley, Richard. 1857 [1833]. An abridgment of Hiley's English grammar. London/Leeds: Simpkin & Marshall/Spink.

Hodson, Thomas. 1802. The accomplished tutor. London: H. D. Symons.

Horsfall, William. 1852. Horsfallian system of teaching English grammar. Halifax: N. Burrows.

Hort, William J. 1822. An introduction to English grammar. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown.

Howe, Samuel L. 1838. The Philotaxian grammar. Lancaster: Wright & Moeller.

Hubbard, Austin Osgood. 1827. Elements of English grammar. Baltimore: Cushing & Jewett.

Hunter, John. 1848 [1845]. Text book of English grammar. London: Longman, Brown, Green & Longman's.

Hutchinson, James. 1859 [1850]. Practical English grammar. London: Wright, Simpkin & Co.

Ingersoll, Charles M. 1824 [1821]. Conversations on English grammar. Portland: Charles Green.

Kavanagh, Maurice D. 1859. A new English grammar. London: Catholic Publishing & Bookselling Company.

Kigan, John. 1825. A practical English grammar. Belfast: Simms & M'Intyre.

King, George. 1854. A new and comprehensive grammar of the English language. Coventry/London: G. R. & F. W. King/Whittaker & Co.

Kirkham, Samuel. 1841 [1820]. English grammar in familiar lectures. Rochester: William Alling.

Kirkus, William. 1863. English grammar for the use of the junior classes in schools. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green.

Latham, Richard G. 1853 [1843]. An elementary English grammar. Cambridge: John Bartlett.

Lennie, William. 1863 [1812]. The principles of English grammar. London: T. J. Allman.

Lewis, John. 1825. Analytical outlines of the English language, or a cursory examination of its materials and structure. Richmond: Shepherd & Pollard.

Lindsay, John. 1842. English grammar for the use of national and other elementary schools. London: J. G. F. & J. Rivington.

Lovechild, Mrs. 1831. The child's grammar. London: Henry Baylis.

Lowres, Jacob. 1862. Companion to English grammar. London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts.

Lynde, John. 1821. A key to English grammar. Woodstock: Watson.

Macintosh, Daniel. 1852. Elements of English grammar. Edinburgh: Sutherland & Knox.

M'Culloch, John M. 1834. A manual of English grammar. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

M'Intyre, William. 1831. An intellectual grammar of the English language. Glasgow: n.p.

McMullen, James A. 1860. A manual of English grammar. London/Dublin/Belfast/Glasgow/ Edinburgh: Mair & Son/McGlashan & Co./ Simms & McIntyre/Robertson & Sons/J. Menzies.

Marcet, Jane. 1835. Mary's grammar. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

Martin, Thomas. 1824. A philological grammar of the English language. London/Birmingham: Rivington & Whittaker/Beilby, Knott & Beilby.

Mason, Charles P. 1858. English grammar. London: Walton & Maberly.

Morgan, Jonathan. 1814. Elements of English grammar. Hallowell: Goodale & Burton.

Munsell, Hezekiah Jr. 1851. Manual of practical English grammar, on a new and easy plan. Albany: J. Munsell.

Murray, Lindley. 1805 [1795]. English grammar, adapted to the different classes of learners. Hartford: Oliver D. Cooke.

Nutting, Rufus. 1823. A practical grammar of the English language. Montpelier: E. P. Walton.

Oliver, Samuel. 1825. A general, critical grammar of the Inglish language. London: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy.

Parker, Richard G. & Fox, Charles. 1835 [1834]. Progressive exercises in English grammar. Boston/New York: Crocker & Brewster/Leavitt, Lord & Co.

Pinnock, William. 1830 [1829]. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Poole & Edwards.

Priestley, Joseph. 1833 [1762]. English grammar. London: Rowland Hunter; C. Fox.

Putnam, John M. 1828 [1825]. English grammar, with an improved syntax. Concord, NH: Jacob B. Moore.

Quackenbos, George P. 1868 [1862]. An English grammar. New York: D. Appleton & Company.

Salmon, Nicholas. 1806. Archai; or, the evenings of Southill. London: Mawman.

Slater, Mrs John [Eliza]. 1830. One hundred and ten aphorisms. London: Suttaby, Fox & Suttaby.

Smith, Roswell C. 1841 [1831]. English grammar on the productive system. Hartford: John Paine.

Smith, Harriet. 1848. English grammar simplified. Bath/London: Binns & Goldwin/Houlston & Stoneman.

Spear, Matthew P. 1845. The teacher's manual of English grammar. Boston: William D. Ticknor & Co.

Spencer, George. 1851 [1849]. An English grammar, on synthetical principles. New York: Mark H. Newman & Co.

Sullivan, Robert. 1861 [1843]. An attempt to simplify English grammar. Dublin: Marcus & John Sullivan.

Turner, John. 1843. The intellectual English grammar. Brighton/London: J. Tyler/Whittemore & Saunders & Son; R. Groombridge.

Ussher, Neville. 1803 [1785]. The elements of English grammar. Haverhill: Galen H. Fay.

Webster, Noah. 1831. Rudiments of English grammar. New-Haven: Durrie & Peck.

Weld, Allen H. 1848 [1845]. Weld's English grammar. Portland: Sanborn & Carter.

Wells, William H. 1847 [1846]. A grammar of the English language. Boston: John P. Jewitt & Co.