A photograph taken in Boston in 1901 shows P. J. Hagerty’s saloon in Boston (see figure 1). Hagerty’s name is just above the door, but it is dwarfed and significantly upstaged by the Roessle Brewery’s two signs. It is unclear from the photograph what the relation of the two men pictured in it is to the saloon; the man in a barkeeper outfit may be Hagerty. However, the relationship between the saloon and the brewery seems clear: the obligation to put the Roessle’s signs over his saloon—and probably to serve only Roessle products on tap—was likely part of a contract Hagerty had to sign in order to receive a loan. This loan tied the saloonkeeper to the brewery, one of the variations of a system that was referred to as the “tied system.” The Roessle Brewery’s account books show that between 1897 and 1900, Hagerty received loans for a total of nearly $4,000, and that he made regular payments until his loan was paid off in September 1900. Hagerty, as will be seen in this article, was a statistical outlier because most saloonkeepers of the era put up very little collateral and frequently did not repay their loans on a regular schedule, if they repaid the loans at all. Nevertheless, in the records of the three breweries examined for this article (the Suffolk, the Boylston [also known as the Haffenreffer], and the Roessle), the brewery owners continued to loan large sums of money. Indeed, in the years for which records exist (except for 1902), these three breweries loaned more money to saloonkeepers than was repaid.

Figure 1 P. J. Hagerty’s Boston saloon on the south side of Beach Street, near the corner of Atlantic Avenue (courtesy of Historic New England).

Why would these firms contract with deadbeat saloonkeepers rather than own and run the saloons directly? This article investigates the economics of forward integration in the brewery industry in Boston at the turn of the last century in order to answer this question. The underlying theoretical framework is the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) paradigm, which I use to examine the market environment in Boston in comparison to the British beer market. Footnote 1 Boston’s large number of consumers of beer (given its German and Irish immigrant populations), and its distance from major breweries in other large cities (such as New York and Philadelphia) and from the major shipping breweries of the Midwest, all contributed to a different strategy. I draw on Michael Porter’s theory of strategy and Oliver Williamson’s work on transaction costs to suggest why these American brewers’ strategies of forward integration were so different than those of their British counterparts. Footnote 2 Using data from three turn-of-the-twentieth-century Boston breweries, I argue that what seems to be an irrational and unsustainable strategy (the ever-increasing lending, shown in table 1) was actually a transaction cost necessary for the breweries to maintain their access to consumers through an artificially limited number of retail outlets. Capital lending was a lever of power used to tie saloonkeepers to their brewer-suppliers, yet the competitive lending market (in the context of a legislatively restricted retail market) also meant that saloonkeepers had a certain power vis-à-vis the breweries. Debt was—as everywhere—a lever of power. It was, however, a smaller lever in Boston than elsewhere; it was large enough to move a keg of beer but not much larger.

Table 1 Data for amalgamated loans and repayments

Note: This data is for the available years for the three breweries discussed in this article. The year 1902, in which a strike occurred, was the only one in which breweries had a positive net on loans.

The Archive: Entries and Silences

In 1790 American physician and reformer Benjamin Rush published a pamphlet on temperance that provided a “thermometer” of beverages, calibrated to their effect on morals. “Small” (low-level alcohol) beer led to happiness, while porter and strong beer gave “nourishment when taken only at meals and in moderate quantities.” Footnote 3 By the 1850s, even this grudging acceptance of stronger beer had evaporated to some degree, with Maine leading the way with its total prohibition of alcohol in 1851. Other states, including Massachusetts, passed laws that allowed individual municipalities to restrict alcohol, although the temperance movement succeeded in getting the Eighteenth Amendment passed in 1919, which outlawed wholesale the production and sale of most alcoholic beverages.

Prohibition, as the failed experiment in extreme temperance is known, led to the closure of hundreds of American breweries. Footnote 4 Although repeal came in 1933 with the Twenty-First Amendment, the fourteen-year period created many archival silences as breweries closed and their records were lost. Only two Boston breweries survived Prohibition, one of which was the Haffenreffer Brewing Company. Footnote 5 It limped through the post-World War II reordering of the American beer market and finally closed in 1964. While I will use other archival records to more fully describe the marketplace that saloonkeepers and breweries occupied in Boston’s pre-Prohibition economy, the documents in the Haffenreffer collection constitute my primary source. The bulk of the documents in the collection are dated between 1896 and 1903. In 1890 an English syndicate bought three above-mentioned Boston-area breweries: the Suffolk, the Boylston, and the Roessle. Because the Meetings and Minutes books for the Committee of Management are records of all three breweries, they provide a broader picture than could be derived from the archives of just one company. Footnote 6

Each month’s minutes began with a series of statistical information, such as managers’ reports on the number of barrels produced, amount of sales, pounds of hops and malt purchased, etc. Another important series of entries in this quantitative information were loans made to and repaid by saloonkeepers. Between October 1897 and November 1903 (the years for which there are Committee of Management minutes), there were 499 entries for loans made by the brewers to the saloonkeepers and almost 1,600 entries for loans repaid. Brewers would often make a yearly loan—usually in April, right before the saloonkeepers needed to pay for a new liquor license—and the saloonkeepers would repay them slowly over the course of the year. That said, there were both small and large loans made throughout the year: the small loans to regular customers often had no notations and the larger ones to new saloonkeepers sometimes listed what security was given for the loan (such as promissory notes, mortgages, or life insurance policies).

In addition to this quantitative information, the minutes recorded conversations and even arguments between the three breweries’ managers on the day-to-day management of the business, as well as pointed questions about finances from New York-based lawyer Samuel Untermyer, who represented the English parent company. Indeed, his presence forced the brewers to justify their decisions and added depth to the discussions. The text of these minutes allowed me to go beyond simple conclusions from the loan data to discuss the types of securities used by saloonkeepers and accepted by brewers for loans. This data—including discussions of other breweries, local liquor license regulations, federal taxation, and the 1902 brewery workers’ strike—reveals the limits of the tied system, which is discussed below.

As Michel Rolph Trouillot observed, archives contain not only voices but also silences; the construction of the archive and the documents it contains encourage selective retrieval and allow only some stories to be told. Footnote 7 From the pages of the Minutes, there is nearly no mention of brewery workers (for example, their salaries) or the day-to-day supply lists of saloonkeepers. Neither do they offer an idea of the percentage of saloons in Boston either tied or completely independent. The saloonkeepers that appear in these records are only those who owed money to the brewers. While I can piece together a few other details about P. J. Hagerty, most of what I know of him comes from the period when he owed Mr. Roessle money, not when he owned his saloon free and clear. These documents, then, did not allow me to tell the story of the brewery workers (my original intended subjects) and did not allow for a complete discussion of turn-of-the-twentieth-century saloonkeepers. They did, however, permit some inferences about the bargaining power of saloonkeepers, their actions, and the conduct of their business partners—Boston brewery owners.

The Tied System in the United Kingdom and the United States

The structures of any market create both advantages and disadvantages for firms either to partially or fully forward integrate rather than to operate in a completely free spot market. In the UK brewery industry, owning retail outlets (called a first-order tie) meant that brewers had a guaranteed distribution network as well as more control over how house staff (or the tenant publican) treated customers, how the product (mainly keg beer) was maintained and presented, and how the outlet was furnished and maintained. Footnote 8 Purchasing retail outlets was, however, capital-intensive and had obvious opportunity costs: the capital used to purchase, maintain, and possibly also staff these outlets was then unavailable for research and development, advertising, or other uses. The intermediate solution was partial forward integration of the breweries through contracts with an independent saloonkeeper that created certain contractual obligations on both sides. Footnote 9 These contracts offered a stable, and often discounted, product price for the saloonkeeper as well as (in some cases) logistical and financial support. The overhead costs for a saloon were considerable, and they included not only capital outlays for fixtures, but also often for licensing fees. In return for the support, the retailer might be obliged to take a brewer’s products or to vend those products exclusively (that is, not offer competing brands).

These contractual considerations make the relevance of Oliver Williamson’s work on transaction costs to the forward integration in the brewing industry clear. Contracts that stipulated that a saloonkeeper or publican sell only the supplying brewery’s beer was a vertical restraint that kept retailers from pursuing what Williamson calls “subgoals.” Footnote 10 These might include appealing to a broader clientele by offering more than a single brewery’s products. These restrictive clauses worried brewery regulators because they seemed to raise entry barriers to an industry by precluding the use of tied houses for distribution. British brewers, for their part, argued that these tied contracts actually lowered barriers of entry to saloonkeepers, who otherwise would not have had access to credit on such good terms. Footnote 11 Interestingly, tied contracts supposedly allowed for the policing of tied houses by brewers to better maintain brand image, but this concern is absent from the American records examined for this article. The Haffenreffer Records do not make a single mention of enforcing any sort of standard décor or even handling of the beer. Footnote 12 That said, many of these market restrictions were present in a 1907 contract between a brewery and Boston-area saloonkeeper Lawrence Killian. Killian had to sign both a promissory note and an agreement with the Harvard Brewing Company to supply him with the capital needed to outfit his saloon, as well as a guarantee to get “the lowest price at which your [Harvard Brewing Company’s] products are sold to the retail trade in Boston.” Footnote 13 In return, the contract stipulated that Killian buy exclusively Harvard Brewing Company beer and that he put a large company sign over his door. Although not recorded in the contract, Killian later argued in court that he had also been guaranteed a premium if he purchased more than 750 barrels of beer a year and, in addition, would not be charged any interest on his promissory note. Footnote 14

Given these basic market structures, the very different strategies of British and American brewers are striking. British beer production and consumption had been, until the expansion of the railway network in the 1830s, quite local. In what is essentially an archival lament about the paucity of records, Gourvish and Wilson note that little is known about distribution because brewer–publican contracts were mostly unrecorded. It is difficult to know the extent to which these markets were monopolistic or to what extent publicans were in debt to their suppliers. One place that the tied system was clearly important was London, as the inflation of the Napoleonic period led to the expansion of the tied system. Footnote 15 Brewers acquired both leases and the loan ties in order to control publicans. Railroad networks and legislation that removed restrictions on public houses led to a dramatic increase in both per capita British beer consumption and number of public houses from the 1830s onward. The expansion in the rate of consumption began to slow toward the end of the century; along with the entry of major new competitors to the market and the increasing value of loans (partially a result of the restriction of the number of licenses in 1869), competition intensified. Footnote 16 Brewers were under contemporaneous pressure to upgrade their plants (e.g., with steam power, refrigeration, and modern bottling technology) as well as to give larger loans to a smaller number of potential publicans.

A change in UK corporate law in 1884 provided a solution: brewers converted their companies into limited liability corporations and capital was provided from the issuance of debentures (some capital also came from banks). Footnote 17 These securities came without voting rights or preserving family power over many breweries, and were issued with fixed, not variable, rates of interest depending on profit. D. M. Knox has argued that most of the capital raised from debenture sales was used not primarily to increase capacity but to have more money to lend to licensees or to purchase retail outlets. Footnote 18 The British syndicate that owned the three Boston breweries discussed in this article used some of the money that Hagerty paid for beer and in loan servicing to then repay their debenture obligations.

Another external shock that nudged breweries toward ownership of retail outlets was a change in British law: the license inhered was for the actual building of the pub, not issued to a person.

[The situation] gave premises holding such licenses a special value over and above that of the premises themselves, and the acquisition of premises having such ‘monopoly value’ (as it came to be called) required greater capital than was possessed by the class of people wishing to enter the retail trade. Footnote 19

The result was that, whereas at the beginning of the nineteenth century British beer had largely been a semi-monopolistic, local, spot market, by the end of the century it was a competitive national market with a high degree of full forward integration. The combination of limited liability corporations and the legality of debenture issues raised the threat of new entrants into the brewing industry in the United Kingdom and forced a change in strategy toward more full forward integration.

Brewing was one of the largest manufacturing sectors in the United States in the nineteenth century and a significant source of revenue for the federal government, and, as occurred in the United Kingdom, there was large increase in total production and per capita consumption of beer from 1863 to 1865: U.S. beer production doubled from 1.7 million barrels to 3.5 million barrels. This enormous growth in productive capacity continued through the post-Civil War period until the 1890s. In that same period—fueled largely by increasing immigration from beer-drinking countries such as Ireland and Germany—the per capita consumption of beer increased from 3.4 gallons to 15 gallons per year. Footnote 20 While these immigrants certainly drank beer, they also sold it: many of the saloonkeepers in my sources had either German or Irish last names: Bamberg and Bohan, Gahm and Gallagher, Hellbach and Hagerty. This incredible increase in production was driven by a number of technological innovations. First and foremost, the expansion and consolidation of the railroads allowed for brewers to ship their beer to new destinations. The spread of pasteurization and the pioneering of artificial refrigeration were key developments in the production of better beer that could keep longer. Contrary to popular belief, this was also the period in which lager began to rival ale and porter for production. Footnote 21 The increase of the production of lager was driven first by central European consumers who preferred it and then by refrigeration. Lager (the German word for “warehouse”) is a kind of beer that required a longer ageing period at cooler temperatures than ale or porter, which meant that ale-centric breweries had to be retrofitted with expensive lager “caves” (e.g., insulated basements) and later with refrigeration. Footnote 22

While much of this increase in production came from large brewers that could ship their beer farther than the city limits, there were also mid-level breweries that shipped on a regional basis. In the larger Eastern seaboard cities of New York, Newark, and Philadelphia, certain breweries that rivaled the mid-Western giants Pabst and Anheuser-Busch as far as output did not ship their beer, or if they did, it was only on a very limited scale. For example, the Hells Gate Brewery, one of the largest breweries in the United States in 1890, sold most of its beer in the New York City market where it was located. Unlike the mid-Western breweries in smaller cities, the production of large-city brewers could all be absorbed by the city in which they were located. Footnote 23

Martin Stack wrote that “shipping breweries” in the 1890s, the period on which this article focuses, began to lose their competitive advantage. In contrast to the trend in the three decades that followed the Civil War, between 1890 and 1920, the number of local, smaller non-shipping breweries steadily increased. Stack attributes this to these breweries piggybacking on technological changes introduced by the larger breweries; Footnote 24 also important may have been the new emphasis on stock and the rise of the managerial class described by Alfred Chandler. Footnote 25 Another challenge to the profits of the shipping breweries was the non-shipping breweries’ ability to better control the distribution of their product. The tied system went into widespread use in the United States as early as the 1870s, perhaps in part because brewers needed capital to pay for the expensive plant improvements that their British colleagues were facing. Stack and others have investigated American pre-Prohibition beer production, and saloons have been the subject of scholarly attention, yet little research has been conducted on the connection between the two kinds of firms. Footnote 26 What is still unclear about the American brewing industry of this period is the character of the tied system: Why did brewers in the United States prefer to use a loan-tie rather than purchase retail outlets? More specifically, why did breweries in Boston seem to lend money at a rate far higher than these loans were repaid?

The trade press of the day, popular histories of brewing, and even some of the secondary academic literature are not helpful in resolving the paradox of brewers lending capital to debtors who were very inconsistent in meeting their obligations to repay the debt. Recent work on breweries either ignores the tied system in the United States or offers conflicting accounts of it. Despite the centrality of saloons and the tied system to the American brewing industry in the late nineteenth century, it is difficult to find mention of them in trade publications. A documentary history of the U.S. Brewers’ Association made at that time does not have a single reference to the tied system and has only five references to saloons. Footnote 27 An anonymous (and perhaps fictional) account penned in 1908 describes a naïve, aspiring saloonkeeper conned into taking on a lease by brewery agents. The anonymous author of the article makes it clear that his agreement with the brewery made him little more than an overworked, poorly paid employee. Footnote 28 Hermann Schlüter’s partisan history of the brewery workers’ union, published in 1910, suggests that owners of rapidly expanding breweries actively worked to make saloonkeepers their “mere agents” Footnote 29 ; current scholars reiterate this view. Labor historian Madelon Powers, commenting on the tied system, asserts that “many urban barkeepers by the early 1900s were essentially hired hands, as subject to the directives of their brewery bosses as their wage-earning customers were to their employers.” Footnote 30 Perry Duis—author of another important history of saloons—also conceived of the Boston tied system as fully forward and integrated, one with little autonomy on the part of the saloonkeeper. Footnote 31 A popular history of brewing in the Unites States echoes this view, adding that expensive municipal license fees (especially relevant to the present research) ultimately made full brewery ownership—not simply the extension of credit to independent saloonkeepers—the national norm. Footnote 32 Beer historian Maureen Ogle, in her book Ambitious Brew, points to the licensing fees as a brewer’s point of leverage:

The barkeeper, leashed to his brewer, had no choice but to pay the brewer’s prices, not least because he was already in debt to him for the price of the license, the fixtures, and perhaps his first month’s rent. The only way an otherwise honest man could make a tied saloon profitable was by steeping himself in the dishonesty of gambling or prostitution. Footnote 33

Ogle also quotes the brewers’ association trade journal, which, conversely, gave the impression that the saloonkeepers regularly took advantage of the vulnerable brewery agents. The trade journal recounts how the dishonest saloonkeepers played an underhanded game with brewery agents by, for example, threatening to switch away from one supplier to another. This allowed the saloonkeeper to take advantage of both agents. Footnote 34 This schizophrenic view of the tied system in the United States is likely the result of a lack of available quantitative data on financial relationships of saloons and breweries.

Brewing in Boston

Because of Boston’s geographic position, local breweries dominated its beer market. Footnote 35 Boston was too far away from mid-Western large- and medium-sized shipping breweries to penetrate effectively. The nearest large city was New York City, but, as already mentioned, its population absorbed all of the beer that its local brewers could produce. Boston’s first large brewery was opened in the late eighteenth century, and by the late nineteenth century there were more than twenty-six breweries operating in the City of Boston. This gave Boston the highest number of breweries per capita in the United States, and these breweries were mostly concentrated in the Jamaica Plain area, which was just outside the city proper. Footnote 36 In his dynamic theory of strategy, Michael Porter noted that competitive advantage cannot be examined independently of competitive scope. What Porter calls scope includes the array of buyer segments served as well as the geographic location and its degree of vertical integration. Footnote 37 As made clear in the discussion below, these are relevant for understanding the conduct of the brewers and saloonkeepers in the Boston market.

Given the relative unimportance of bottled beer at this time, drinking beer required going to a hotel or saloon that held a liquor license and drinking on-site or purchasing beer in a takeaway container (called a growler). Footnote 38 In 1881 the Massachusetts legislature passed a law that gave towns what was called “the local option.” This meant that while there was no state-level prohibition, towns could either ban liquor or issue licenses for its sale. Footnote 39 Although Boston was safely “wet,” the brewers were worried about the outlying towns opting for the “dry” solution. One of the managers expressed his concern for sales in Lowell, which in 1899 had gone dry, but stated that he was confident that the decision would be reversed in the next election. This is not surprising, considering an entry from the next year: “$305 is for contributions to the election funds of the various towns and cities outside of Boston where we do business.” Footnote 40 The City of Boston, while not outlawing the sale of alcohol, did adopt a licensing structure that became progressively more restrictive. Initially, it limited the number of licenses to one licensed retailer of alcohol per five hundred residents of the city. Licenses were expensive, initially $150 in 1884, $500 in 1887, and $1,000 for the “common victualler” license used by saloons in 1890. This would be $26,606.02 in 2015 dollars, quite the sum for a prospective saloonkeeper. Footnote 41 Pressure from groups such as the Anti-Saloon League, founded in 1893, only solidified the licensing structure.

Debt and capital lending were important parts of the Boston market, as is clear from the minutes of a meeting of the members of the Committee of Management of the New England Brewing Company, held on December 16, 1900. The company was a conglomerate of the three Boston-area breweries—the Suffolk, the Boylston, and the Roessle—bought in 1890 by an English syndicate. The syndicate retained all three owners as the Committee of Management. Present at this December meeting were two of the former brewery owners, Rudolph Haffenreffer and S. C. Stanley, as well as Alvin Carl, who represented the Roessle Brewery, the largest of the three breweries. Also present was Untermyer, the previously mentioned New York-based representative of the English syndicate; Untermeyer was a crucial go-between for British capital acquiring American breweries. Footnote 42 The meeting began—at least as far as can be told from the minutes—with some discussion of adjusting a claim to what “was supposed to be a doubtful asset” before moving to the topic of new loans. Untermyer reminded the managers that any loans above $1,000 first had to be discussed and have the unanimous vote of the other managers. Footnote 43 Each manager then made a brief report of the loans he had recently made. One report is worth quoting in full:

A loan of $2,500 to Jaeger & Imbeschied, secured by a second mortgage on real estate and by the personal endorsement of both the parties, who are responsible. It is a demand loan, and is subject to the agreement that from $50 to $100 per month is to be paid on account, with interest on the loan at five per cent. These customers are large consumers of beer. They are also interested in the Massachusetts Brewing Company and have since discarded the beer of that company in favor of the Roessle Brewery. On motion, duly seconded, both these loans were approved. Footnote 44

This brief description of a loan to Jaeger & Imbeschied contains all of the elements of the channel structure in Boston that I hope to illustrate in this article: the importance of brewery loans to saloonkeepers, the security that saloonkeepers offered to brewers to get these loans, and the other structural constraints on performance that impelled brewers to grant loans even when the security offered was not convincing. The ledgers suggest that saloonkeepers were neither hat-in-hand debtors who were totally beholden to the brewers, nor were they tricky shysters switching back and forth between suppliers at the drop of a hat. What is suggested here, and what emerges from the brewery records, is that saloonkeepers attempted to make a living while uncomfortably situated between their suppliers (the brewers) and their customers, between the law (liquor license regulations) and religious fervor (the temperance movement), and—most importantly—between solvency and insolvency.

When Hagerty started his saloon, he needed bars and stools and glasses, as well as a license. Killian’s contract specified that he would use the $18,000 that the Harvard Brewing Company loaned him for “license paper” ($6,500), the license fee itself ($1,400), and for fixtures and equipment ($12,000). Footnote 45 In the Haffenreffer Records, loans in the earlier minutes books are often richer in description, while later entries are often quite vague. Some offer only a notation of the amount of the loan, the recipient of it, and the security, if any, offered. In 1897, Ultsch, Koch & Co. requested a loan of $5,000 “to enable them to build a store for their own use, and a dwelling over the same, also a stable, upon a lot they recently purchased, said loan to be secured by a first mortgage on said lot and building.” Footnote 46 Before the era of zoning ordinances that separated residential and commercial property, it was common for small-business owners to live in the same building as their storefronts. As discussed below, this close association of business and home also allowed for the saloonkeeper to integrate members of his family into the business of the saloon, something that scandalized temperance proponents.

At the same meeting where they gave Ultsch, Koch & Co. a loan, the Committee of Management also approved a loan to J. Tehan, who wanted to buy the Higgins Oyster House. The previous owner, John Judge, was heavily indebted to two of the breweries, owing the Suffolk Brewery $3,500 and the Roessle Brewery $5,500. The managers approved a new $3,000 loan to Tehan, who agreed to assume Judge’s debts; he secured the loan with a “first mortgage on lease, license and contents of the Higgins place.” Footnote 47

The license issue in Boston was one of fundamental importance for the saloonkeepers’ relationships with the breweries. On May 1, 1889 (just before the British syndicate bought the three breweries), the Boston Daily Globe reported that the new licensing cap had gone into effect and that two thousand licenses to sell alcohol in the City of Boston had not been renewed. The paper underlined the power of the temperance movement even at this early date, noting that thousands of men had been thrown out of work and “many thousands of dollars of property is wiped out of existence by this legislation.” Footnote 48 One Bostonian, whose last name was Notrom, called this “an act of tyranny.” Footnote 49 Considering that by 1898 no less than 250,000 of Boston’s inhabitants—or 50 percent of the total population—visited a bar every day, one can imagine there would be substantial agreement. Footnote 50 A grand total of 1,000 licenses to sell “intoxicating liquor” Footnote 51 were to be meted out by the Board of Police on an annual basis. The effect of this was to create a premium on liquor licenses, over and above the actual $1,000 price.

This outcome was apparent years before the licensing limit went into effect. A representative of the city told the Boston Daily Globe that a limit on licenses would create a premium as high as $250,000, and he was in favor of the city conducting the auction and the proceeds going into the city’s coffers. Footnote 52 While the economic effect was not as pronounced as predicted, a premium did develop. Instead of being a windfall to the city, the premium was set by the market. Despite attempts to make premiums illegal, the licensing board “approved the recognition of the premium as an asset in bankruptcy or probate proceedings and allowed it to be sold or inherited.” Footnote 53 There were, however, limitations to the license-as-asset scheme: unlike real estate property, liens were prohibited starting in 1901. The managers of the three breweries discussed this decision by the Board of Police at length, at first worrying that the decision would “diminish the security of brewers lending against saloon property.” Footnote 54 However, the committee ultimately decided:

The regulation in question should not be permitted to interfere with the conservative lending of money on saloon property, as after all the security depends on that success of the business; if successful the brewers are paid, and if unsuccessful the license is worthless in any event. Footnote 55

This passage makes it clear that the brewers had up to that point been using liens against the licenses rather than the property to secure their loans, and in the case of bankruptcy of a saloon, only the nominal and premium parts of a license’s value were assets, not the liens against it. Even though brewers knew liens would not be recognized in court, at least one loan was secured with it after the 1901 prohibition. Footnote 56

The costs of opening a saloon in Boston were thus high. Some Bostonian barkeepers decided that they could more afford the risk of being caught without a license than the risk of borrowing the necessary funds for one. Footnote 57 Other than perhaps increasing the number of illegal saloons, the results of these growing start-up costs were two-fold. First, in an attempt to gather the capital necessary while maintaining a degree of independence from the breweries, more saloons in Boston were partnerships as opposed to individual proprietorships. Of the ninety-six different recipients of loans from the breweries in the period recorded in the Minutes books, twenty-seven were explicitly partnerships. Footnote 58 I conjecture that this number means that most partnerships had sufficient capital to not need loans from the breweries; nevertheless, the presence of a significant number of partnerships also shows that even pooling resources was sometimes not enough to overcome the increased need for start-up capital.

Second, prospective saloonkeepers turned to the breweries for loans. Not surprisingly, Untermyer, in addition to reiterating that the managers needed to discuss all loans above $1,000, also motioned that “the character of the security offered for the loans” be presented before loans were granted. Footnote 59 Prospective saloonkeepers offered a wide variety of collateral with their loan requests. At a special meeting with the managers and their legal counsel, the Harrington brothers of Charlestown requested the relatively small amount of $500, with “said loan to be secured by deposit of whiskey certificates.” Footnote 60 Shares such as these, as well as stocks and bonds, were unusual as securities for loans, although there is one other instance in which “a security of $5,000 of quarry stock, which is payable in dividends” was given for a loan of $2,000. Footnote 61 Another relatively uncommon security was a life insurance policy. In one of the nine ledger entries that contain the phrase, William Hellbach received $2,000, having signed a chattel mortgage “and assignment of life insurance policy for $5,000, also lease.” Footnote 62 Chattel mortgages were mentioned in 33 of the 499 loans recorded, and saloon historian Perry Duis makes explicit that they often contained a clause that made the “tied” relationship explicit, prohibiting the saloonkeeper from selling anyone else’s beer. Footnote 63

The vast majority of the notations concerning the collateral offered to the brewers for loans contain some variation on a personal promissory note (e.g., “note,” “demand note,” “time note”) either alone or with another security such as a mortgage or with an endorsement. Of the 499 loans, 138 contain an annotation with “note” in it. Of Hagerty’s six loans, only one had an annotation of collateral offered at all: in May 1898, he received $800 “on note.” Killian had also signed a similar note with the Harvard Brewing Company. On October 7, 1907, he agreed to pay “on demand” $2,500 at any bank in Boston, with 6 percent interest until paid. Footnote 64 The Massachusetts Supreme Court had ruled in 1894 that conveying notes when either “insolvent or in contemplation of insolvency” was a fraud, and brewers were, of course, aware that a note was only as good as the assets and future wages of the person in question. Footnote 65 A note in the January 1899 minutes reflects this: “Accounts of Simonds and Crafts for $150 and $1,000.00 respectively, charged to Bad Debts, represent judgements [sic] against those parties, which will permit recovery within twenty years provided either of them should become possessed of any property.” Footnote 66

While most of the loan notations are brief, the meeting minutes occasionally (especially in the earlier part of the period examined) provide more information about the criteria used by the managers to vet the applicants. Along with the actual securities, the relationship with the recipient of the loan is sometimes cited. A Mr. Galivan, who had offered the quarry stock as collateral, was judged “an old and valuable customer and perfectly responsible”; at the same meeting, the managers made a loan to Carl Schleicher of $2,000. Schleicher had to sign a demand note, even though the minutes noted “both he and his wife are responsible.” Footnote 67 Saloonkeepers who already enjoyed relationships with the brewers and who could put up at least part of the money for their new businesses were also likely to receive loans. The December 1900 meeting was seemingly only about potential “new trade”; a request from Edward Finnin, a former employee of the Roessle Brewery, is described as “being secured by chattel mortgage.” Finnin proposed to use the $3,500 for part of the price of saloon property, paying the $2,900 balance himself. “It is considered a safe and lucrative investment,” noted the minutes. “On motion, duly seconded, the loan was approved.” Footnote 68

Another variable that seemed to make loans more likely to be approved was one that might lead to a second customer. Along with the assertion that P. C. Crowley was “perfectly responsible,” Alvin Carl (the manager of the Roessle Brewery) pointed out that the loan would secure “his trade in addition to the trade of a son-in-law of Mr. Crowley’s. Upon this statement the loan to Mr. Crowley is unanimously approved.” Footnote 69 The best of all worlds for the brewers, though, was an existing customer who made large purchases. To return to the example of the Jaeger & Imbeschied loan that this section began with: “These customers are large consumers of beer. They are also interested in the Massachusetts Brewing Company and have since discarded the beer of that company in favor of the Roessle Brewery.” Footnote 70 With only one thousand possible outlets for their beer in the Boston market, the brewers were constantly worried about expanding their trade vis-à-vis other breweries. That is not to say that all applications were approved: the “Application of Mr. O’Connor for $3,500 […] was declined for the reason that he could offer no security and that he was not regarded as a desirable customer.” Footnote 71

From Entrepreneur to Employee: The Exceptional Case of P. J. Hagerty

Perry Duis, in his account of saloons in the urban history of Boston and Chicago (in a chapter entitled “From Entrepreneur to Employee”), highlights the visible changes that occurred as the tied system spread through U.S. cities. Duis cites the change in signage, asserting that while in the past the name of the saloon owner had been prominent, “after the brewer took over, its brand and its symbol were the largest things on the door. […] The entrepreneur had become the employee.” Footnote 72 The photograph at the beginning of this article seems to prove Duis’s assertion, as does the clause in Killian’s contract with the Harvard Brewing Company to place the sign “Harvard Beer and Ales” above his door. Footnote 73 In figure 1, the larger of the two Roessle signs is more visibly luminescent compared to the two signs below it; its whiteness suggests newness, whereas the other signs seem to have an accretion of soot on them. Does this seeming visual confirmation of Duis’s thesis—that the tied system as it was practiced in Boston represented the final, complete, and economic subjugation of the saloonkeeper by the forward integrating breweries—find corroboration in the archives? As Duis himself points out in the subsequent chapter, “often illiterate and lacking business experience, these small merchants [saloonkeepers] kept very few records.” Footnote 74 Because of the relationship that the tied system created, though, the breweries’ records can perhaps function as a stand-in for the records that saloonkeepers may never even have kept.

Hagerty’s saloon provides a test case for the oppressiveness of the tied system. Hagerty’s name appears in twenty-nine separate entries in the Haffenreffer Records. For the first six repayment entries, Hagerty is listed together with someone who may have been his partner—perhaps one of the two men standing in the doorway of the saloon in figure 1. The entry name “O’Connell and Co. and P. J. Hagerty” make it clear that Hagerty was a later addition to the partnership, perhaps to provide an infusion of capital for the saloon. Between October 1897 and February 1898, the pair made monthly payments of between $100 and $150, although in March 1898, Hagerty was listed by himself for the first time. It is impossible to know how much money the partners owed the Roessle Brewery prior to the beginning of the Haffenreffer Records, but Hagerty received six loans between October 1897 and September 1900 for a total of $3,962. Footnote 75 Between March 1898 and August 1900, Hagerty made mostly monthly repayments of, on average, just under $200. The final payment was quite a bit higher, at $912. Thereafter, Hagerty’s name vanishes from the Haffenreffer Records.

Hagerty’s known life before and after his brief appearance in the Haffenreffer Records is fragmentary at best. The 1900 U.S. census listed him as living at 61 Rockwell Street in Boston’s Ward 24 (Dorchester), together with his mother, Mary Hagerty (born in Ireland, birthdate “unknown”), and his two older sisters, Annie and Ellen. P. J. (full name Patrick James) was twenty-nine years old and his occupation was listed as “liquor dealer.” Footnote 76 The 1910 Boston census does not list any of the four family members, but by 1920 Patrick and his two sisters are back on Rockwell Street, although now several doors down. Patrick was listed as fifty-two years old and as an “upholsterer.” Footnote 77 The years between 1900 (when he is listed in the census and makes his final payment to the Roessle Brewery) and 1920 are difficult to reconstruct. Hagerty’s total for loans received from Roessle was $3,912, and his repayments totaled $3,962. It is impossible to say with certainty—given the fact that the loan history prior to 1897 is not available—but it appears that with his final, unusually large payment, Hagerty paid off his loan account with the Roessle Brewery.

Despite the brewery trade journal’s statement cited above, the data examined here suggests that changing brewery suppliers was an uncommon occurrence. Assuming that Hagerty had, indeed, paid off his loans, it would seem that he continued buying beer from the Roessle Brewery. Hagerty made his final loan payment in September 1900, and in March 1901 he still has the signs for the Roessle Brewery’s premium lager (clearly visible in figure 1). After the final payment, the terms of the agreement may have changed; perhaps Hagerty kept the signs in return for continuing to serve only Roessle products, or perhaps he negotiated a better price for the beer. It is not possible to know whether this relationship continued for long. In 1905 Hagerty applied to the city council for permission to put up “illuminated signs at 151 Beach St., Wd. 7.” Footnote 78 These signs may have read “P. J. Hagerty” in large, well-lit letters, or perhaps they read “Roessle Premium Lager,” but at some point between 1905 and 1920, as made clear from the census records, Hagerty left saloon work for wages as an upholsterer. The question remains of what meaning to attribute to these few dozen entries in ledgers and a single photograph with no subjects identified. Footnote 79 It seems clear that the debt peonage that Duis attributes to the relationship between the brewer and the saloonkeeper, at least in the case of Boston, may be exaggerated. At the same time, perhaps Hagerty was the exception to the rule. Only saloonkeepers who were able to repay their debts as quickly as Hagerty could escape the pseudo-category of a precarious brewery employee. To better understand this, trends in loan making and repayment are needed: this will not only allow Hagerty to be classified as a statistical outlier, but also to see how both saloonkeepers and brewery owners used outstanding loans as leverage.

The three breweries in this sample seemed reluctant to miss the opportunity to loan money to a prospective saloonkeeper. While there was, of course, always the risk that a saloonkeeper would default, there was also the danger that refusing loans to potential saloonkeepers would send them straight into the arms of the competition. Using Porter’s terms, the bargaining powers of the buyers and the competition among the breweries in an artificially small market for retail outlets influenced the conduct of the participants. The risk of default could be lessened through proper vetting, but the danger of losing clients was real, and evidently concerned the brewery managers. In July 1898, Rudolph Haffenreffer made an accounting of the customers he had lost. He reported that several saloonkeeper clients had gone elsewhere because of his “unwillingness to make large and insecure loans,” which they ultimately procured from his competitors. The minutes then record Untermyer recommending to both the committee and to the London Board that Haffenreffer be encouraged “to make conservative loans for retrieving his trade.” Footnote 80 Far from being subservient to a monopsonic lender, saloonkeepers were able to use the fact of limited Boston retail outlets to secure large loans from brewers.

This passage in the minutes is revealing in that it shows how Boston’s industrial product channel put the managers between the proverbial rock and a hard place. Haffenreffer’s comments were not part of a reporting of customers made and lost, but rather a defensive response to Untermyer’s request for “an explanation of the large and continuous falling off in output.” Footnote 81 As I show below, the managers were under constant pressure from both Untermyer and the London secretary of the syndicate to remit money that could then be distributed to holders of the syndicate’s stock and debentures. Katherine Watson has shown that the second wave of British brewery acquisitions of public houses occurred in the late 1890s. The syndicate purchased the three Boston breweries in 1890, just as the first wave of UK public house purchases was beginning. It seems reasonable to conjecture that this American capital was being remitted to Britain not only for the syndicate to provide dividends, but also to be used as collateral for mortgage debt on public houses there. Regardless of what these remittances were for, it is clear from the minutes that they constrained the managers’ ability to make the loans that would ensure future cash flow to pay remittances. During the February 1900 managers’ meeting, after a request from Untermyer to remit the rest of the $70,000 needed for payments to shareholders, the managers complained that further remittances before the May 1 licensing period would make them “very much cramped in the making of advantageous loans [and] in that respect are not able to compete on equal terms.” Footnote 82 At the June meeting of the same year, two of the three managers reported that they had applied for and received large personal loans from a Boston bank. One specified that he had done this “for the purpose of advancing to his customers on May 1st to enable them to pay their licenses and also for several loans which he was compelled to make in order to secure new business.” Footnote 83 This back-and-forth between Untermyer and the managers about the remitting of profits, as opposed to using them to fund new loans, repeats itself in four of the ten years for which there are records. Hatten, Schendel, and Cooper, although discussing the U.S. brewing industry in the second half of the twentieth century, note that one of the key strategic variables for competition within an industry is financial policy. Footnote 84 The intra-industry group of three brewers were clearly in agreement that a greater use of capital for long-term debt would make them more competitive in the Boston market, but their British owners were driven by their own debt requirements, that is, the need to pay debenture interest.

This explains a startling observation that emerges from a close analysis of the data. Despite the admonitions about vetting all loans with a detailing of the collateral offered and making “conservative” loans, 217 of the 499 loans made had no notation at all about the security, not even promissory notes. Given that the average loan in the sample was $1,200 ($34,463 in 2015 dollars), the overwhelming number of loans made could be regarded as risky, according to Untermyer’s threshold of $1,000. Footnote 85 It is in this context—brewery managers’ need to remit money to London with the simultaneous need to use loans to secure what they referred to as “trade” (i.e., saloons as new retail distribution)—it is possible to make sense of the most puzzling aspect of the records: the saloonkeepers systematic failure to pay back the loans they had received.

While some of the notations in the minutes or the entries in the data give payment schedules, it is difficult to find a saloonkeeper that paid according to the agreed-upon schedule or even on a regular basis. This is why Hagerty is the statistical outlier in the data set. An example from the June 1899 meeting is reflective of the overall trend that emerges from the loan data. In the same meeting in which Untermyer exhorts the managers to carefully review all requests for loans above $1,000, as well as the securities offered, Heffenreffer announces that “it will be necessary for him to loan a customer named McNamara $7,000.” Haffenreffer makes it clear that the reason is that he considers it “necessary to retain his [McNamara’s] trade.” McNamara is good for the money, Haffenreffer assures the rest of the committee; he has no doubt that McNamara will pay the $7,000 back within a year. After Haffenreffer states that he will make the loan from his own funds if the company does not advance the money, the committee approves the loan. Footnote 86 McNamara’s repayments are listed in Table 2, which shows that they were both occasional and insufficient to repay the loan.

Table 2 Loan repayments of John McNamara

Note: John McNamara’s irregular and small payments were not sufficient to repay the $7,000 borrowed from the New England Brewing Company.

Other loan recipients, like Hagerty, made good on their loans (Finnin, the former brewery worker, paid back $3,500 within two years), but most were delinquent. In the same meeting in which the managers approved Finnin’s loan, a loan of $2,000 was made to J. J. Donovan “on Donovan’s demand note, with responsible endorsers.” Carl justified the loan by saying: “Donovan has just opened a new place, costing $5,700, he and his partners having paid cash for the entire place.” The difficulty of resisting a loan to a new saloonkeeper—and one with multiple partners and enough cash to buy a saloon outright—is obvious. Donovan made exactly one payment of $100 on this loan, twelve months after it was approved, and thereafter disappeared from the brewery minutes. Footnote 87 Several of the largest loans are the most compelling examples. In July 1898, Enrico Tassinari was given a loan for $13,000, the largest single loan of the entire data set. During the next twenty-eight months, Tassinari made only seven repayments, totaling $1,750. From November 1900 through August 1903, he made no payments at all. His repayments—which can be referred to as “sporadic” only with a generous spirit—was rewarded with a new loan for another $6,000 in July 1903. Footnote 88 Tassinari had evidently taken on his son as a partner, as thereafter his repayments are noted under the name “Tassinari and Son.” From August through November 1903, the Tassinaris repaid $1,000 per month, but unfortunately the data set ends with the close of that year. We can only hope that the younger Tassinari’s apparent good influence continued.

While Tassinari’s first loan is the most egregious example of not repaying what was owed, there are scores of other loan recipients who appeared delinquent in their payments. Given the short time period covered by these data-rich entries, Footnote 89 the number of saloonkeepers that received new (and often large) loans, despite only occasional repayments, is quite large. It seems that debt—or, more specifically, a very fluid and competitive market for new loans from competing brewers—was a tool more often used by saloonkeepers than brewers. Despite frequent discussion of loans in the many recorded regular meetings of the Committee of Management, 114 in all for this article, in only three instances was there even a mention of bad debts, and one of these is noted in the context of possible future collection. That said, the brewers used debt as a lever of power—that is, a strike (which is discussed at length below)—in a moment of necessity.

Why were the saloonkeepers so lax about repayment, and why did the brewers not use the leverage they had more frequently? Ogle cites an exasperated brewery collector, who wrote to the company’s owner:

You would not think of giving this amount of money to any reputable man without security. Why would you give it to strangers who in asking it have to admit that they have not the necessary funds to carry on the business … [T]his kind of loan system is the weakest spot in your whole business and subjects you to more losses, and to more expense and unsatisfactory litigation, than all your other business put together. Footnote 90

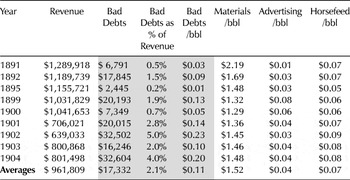

Unless greater financial rationality is attributed to the collector than to the brewery owner, these unsecured loans require explanation. The qualitative data available in the minutes show the importance the managers gave to maintaining their existing saloon clients and to gaining new ones; this data is corroborated by the quantitative data available on the balance sheets prepared each year by Deloitte, Deer, Griffiths & Co. Footnote 91 (see table 3).

Table 3 Data for available years for the amalgamated revenue and expenses for the three Boston breweries

Note: Bad debts were a small portion of the cost per barrel (bbl) of beer.

The balance sheets record the income and expenses for all three breweries and provide expenses both in gross terms and in the cost per barrel. It is clear from even a cursory look at brewery finances that bad loans were treated almost like an operating cost; indeed, several times the entry for “Bad Debts” appears not on its own page but with other operating expenses. Bad debts were a relatively minor expense: over the nine years recorded, the average cost was only $.11 per barrel. This was more than horsefeed and advertising, but it was ultimately a fraction of the major expenses of primary materials (the hops, malt, and water) that, on average, cost $1.52 per barrel. For comparison, the collectors’ salaries and “expenses” (e.g., free drinks for saloon-goers when the collectors made their rounds) were $1.82 per barrel in 1901. The total cost per barrel of federal revenue stamps (i.e., the federal taxes on beer) was $2.03 per barrel. This is not to say that the weight of the loans on the balance sheet was light. Despite revenue of just more than $700,000 dollars in 1901, the combined outstanding loan accounts of the three breweries (present in the minutes books but absent from the balance sheets) totaled $319,452.16. Footnote 92 The year in which bad debts were the highest percentage of the total cost of a barrel of beer was 1902, undoubtedly because of the strike (discussed next). In that year, bad debts amounted to $32,502.31 across the three breweries, compared to total gross revenue of $639,033.13. Even at this low point of the years surveyed, the debts accounted for only 9 percent of the total expenses, and only $0.23 cost on each barrel of beer. Footnote 93

The Strike and Conclusions

In the minutes for March 1902, there is brief reference to “the demand of the labor unions for decreased hours and increased wages,” although there seems to have been little discussion other than a calculation of what acceding to these demands would cost the three breweries. Footnote 94 By the next meeting of the managers, on April 15, 1902, the strike was in its second week. All three brewer-managers reported that they were still brewing in a “more or less satisfactory manner,” and that while many workers were still out, some had come back. The minutes closed with the observation that the Retail Liquor Dealers Association of Boston had voted to use “Boston-brewed” (i.e., scab) beer, and that this would likely lead to a speedy conclusion to the strike.

Despite their predictions, the strike wore on. Some of the city’s saloonkeepers decided to support the strike and refused to take beer brewed by the scabs. The brewery owners turned the screws. In the minutes of their September meeting, the brewers stated: “It was found necessary to demand the payment of large loans made to customers, who by reason of the strike, ceased buying.” Footnote 95 It is, unfortunately, impossible from the records at hand to determine what specific effect that threatened call had, but by the end of that month the strike was over. It seems, given the complaints from the London secretary about the large decline in the number of barrels sold, that the strike had some impact on consumption, but that the saloonkeepers—the crucial link in distribution—seemed to have mostly sided with the brewers. Footnote 96 Although there was undoubtedly some support for the strikers by saloonkeepers, as they initially refused to sell “scab” beer, those with outstanding loans to the brewers could not afford working-class solidarity.

A channel organization diagram (see figure 2), edited to reflect the evidence presented in this article, allows certain conclusions to be drawn about the ultimate absence of complete forward integration in Boston’s early nineteenth-century brewing industry. Despite the fact that a more complete set of documents—for example, at least one saloonkeeper’s account book—would offer a much more definitive set of data on which to draw assertions, the Haffenreffer Records do allow for some conclusions. In contrast to previous portrayals of the tied system, which located all the leverage with either the brewer (the despot with the promissory note) or the saloonkeeper (the unreliable operator free to switch suppliers at any time), the documents surveyed here suggest that the relationship was a more complicated one.

Figure 2 A brewery-specific channel structure showing legal and financial feedback loops. (Based on Scherer and Ross, Reference Scherer and Ross1990.)

While the market structure in Boston—the need for licenses to sell beer—made the brewer the holder of a legally enforceable financial obligation, the saloonkeeper enjoyed a privileged position. Given Boston’s distance from other major centers of beer production, as well as New York City’s ability to consume all of the beer it produced, beer sold in Boston was largely produced by local brewers, another unique characteristic of the brewing market structure in the Hub. Boston was the eighth-largest revenue district in the country in 1907, according to the secretary of the brewery trade association Footnote 97 ; the combination of Boston’s size and isolation created a capital lending market that gave the saloonkeeper a certain advantage. The local brewers’ Board of Trade made attempts to create a cartel to artificially inflate prices and reduce competition between brewers, but its failure is clear in the Haffenreffer minutes. Footnote 98

Because of the small size of the bottled beer trade, the breweries were in competition not so much for consumers as for distributors. Footnote 99 The tight regulation of the number of licenses in the City of Boston and the existence of the local option in the outlying towns and small nearby cities made saloonkeepers a critical player in the beer market. As Wade, Swaminathan, and Saxon have shown in their investigation of restricting alcohol markets, “the normative and resource effects of government regulations often generate externalities, that is, the private costs and benefits for the decision makers are not the full costs and benefits for the decision.” Footnote 100 In other words, governmental distortions of the market conditions created asymmetrical advantages and disadvantages, something clear in these records. Despite their indebtedness to the breweries, saloonkeepers were able to use these market conditions to extract advantageous conditions on loans. The loans thus represented an excellent investment for the brewer; even though repayment on the loans was sporadic at best, the loan guaranteed greater access to the consumer and offered a continuous source of revenue. As shown, the loan was still a guarantee that the saloonkeeper would use only that brewery’s beer, and it was leverage that was used when required, as in the strike.

At the same time, the loan represented a sunk cost for the brewery, in return for which they were able to demand both “brand loyalty” and a steady stream of current income: the payment for the beer itself. Lawrence Killian’s loan agreement with the Harvard Brewing Company specified quarterly loan repayments, but there is no evidence that he was on time with these. Footnote 101 It is telling that the contract specified that Killian had to “pay for all beverages so furnished him once each week, making settlement in full for all purchase made the week previous.” Footnote 102 The Harvard Brewing Company made explicit in their brief that the reason they took Killian to court was that he stopped making weekly payments for product ordered, not that he had not made loan repayments. This evidence forces a reconceptualization not only of the brewery industry in Boston at the turn of the century, but also of the factors in the channel structure that inhibited or promoted complete forward vertical integration. Most studies suggest that saloonkeepers were workers who had little or no capital of their own, Footnote 103 and their need for loans was a crucial part of the Boston brewing channel. While there is evidence of their solidarity with the brewery workers (made clear by their opposition to scab workers), ultimately the saloonkeepers’ ties to capital made their solidarity contingent. Just as tightness of labor markets means higher wages for workers, it seems reasonable to conclude that the constriction of distributive channels into bottlenecks—here by legislation, although other causes were possible—meant the possibility of the extraction of better terms from wholesalers on the part of distributors. Of course, this availability of loans on very easy terms precluded the development of the kind of “laborite” democracy that Helena Flam suggests can emerge in which skilled workers (or at least those with relatively high wages, a category to which at least a few saloonkeepers might have belonged) are well integrated into local real estate and credit markets. Footnote 104

The availability of easy credit from breweries was perhaps also an inadvertent contributing factor to the power of the prohibition movement. Despite a somewhat sympathetic report in 1905 by Boston researchers on the positive role of saloonkeepers in the working-class community, Footnote 105 the saloon was the focal point of the temperance opposition. Middle-class observers at the turn of the century asserted that saloonkeepers sold liquor to minors, kept their doors open until late, and were open on Sundays because the law of demand was “almost the only law that they will obey, and it is this law that we must face and deal with unflinchingly.” Footnote 106 The lack of integration in local financial markets perhaps was one of the elements that prevented saloonkeepers from being seen as upstanding citizens. Their perceived desperation for money led the public to believe that saloonkeepers allowed vice of all sorts to go on in their establishments in order to be able to repay their debts. As noted above, Ogle (who shares these suspicions of the turn-of-the-century prohibitionists) suggests that only by running a combination of a gambling den, brothel, and saloon could a saloonkeeper manage to pay the rent. While the examination of these documents suggests otherwise, the prohibitionists were ultimately able to convince the American public of the evil of saloons. The threat of total prohibition—very real throughout the late nineteenth century, given its occurrence in the nearby state of Maine and the “creeping prohibition” that the so-called local option allowed for—perhaps also contributed to the form of the tied system in Boston. Rather than invest capital in retail outlets that might not be allowed to retail the product, Boston brewers preferred the loan-tie system and its lesser exposure to the losses that Prohibition would mean.

There are other stories that could be told from the Haffenreffer Records, including the managers’ change in status (from owners to what Rudi Batzell calls “functionaries of capital”), Footnote 107 their interest and investment in new technologies, the presence of women in the work involved with saloons, financing, and the relationship between the city’s urban market and Boston’s hinterland. There is evidence for these discussions in the Haffenreffer Records, but they were beyond the scope of this paper. However, the Heffenreffer Records could provide a starting point for further research on these webs of capital. The brewery markets in both the United States and the United Kingdom are still regulated today, so research on the paths that led to the present regulations might provide a way forward.