Introduction

There has been a major increase in the number of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) in Australia over the past three decades and this is likely caused by oral HPV infections acquired through oral sex. A subclinical oral HPV infection that persists for decades is likely to precede an HPV-driven OSCC (proven for cervical cancer) [Reference zur Hausen1]. Almost all cervical cancers are HPV-driven, and other sexually transmissible infections (STIs; i.e., Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG)) can act as cofactors in cervical carcinogenesis [Reference de Abreu, Malaguti and Souza2, Reference Smith, Muñoz and Herrero3]. Compared to cervical cancer, there are several important research gaps in knowledge of persistent oral HPV infection, HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer, and their cofactors. STI rates have significantly increased in the past decade and presumably so have oral STIs. Despite this, the prevalence of oral and pharyngeal STIs is currently not well captured, especially in heterosexual populations where pharyngeal testing of NG is not included in the testing guidelines in Australia (except for sex workers). Furthermore, oropharyngeal infections are generally asymptomatic thus contributing to underdiagnosis. Here, as a first step, we sought to explore CT and NG positivity in individuals with and without oral HPV infection using a saliva sample bank collected from the general population [Reference Antonsson, de Souza and Wood4].

Methods

Testing was conducted retrospectively on our previously established longitudinal cohort, the Oral Health Study (OHS) [Reference Antonsson, de Souza and Wood4]. Oral samples and questionnaire data (lifestyle, health, Gardasil vaccination, sexual behaviour, and history) were available for OHS participants. Participants (n = 636) donated an oral sample at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months. Samples were previously tested for HPV (positive samples were HPV typed) as described [Reference Antonsson, de Souza and Wood4]; samples were extracted using the Promega Maxwell system, HPV was detected with a nested PCR system, and positive samples were typed by direct sequencing.

For this sub-study, we selectively tested two participant groups, (1) at least one HPV-positive oral sample (n = 132) and (2) HPV-negative (n = 180). In total, 547 samples from 312 people were tested. The participants were recruited from workplaces (n = 69), GP clinics (n = 127), STI clinics (n = 44), and university campuses (n = 72). Saliva samples were tested for CT/NG in duplicate on the Cepheid, GeneXpert commercial platform (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). It should be noted that saliva is not a validated sample type for the GeneXpert CT/NG test; hence, this testing was research-use-only.

Results

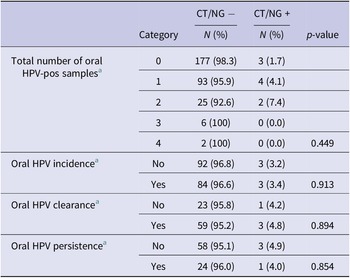

Overall, 10 of 547 samples tested for CT/NG did not pass the quality control and were excluded from analyses. Valid results were obtained for the remaining 537 samples (n = 312 participants). Nine oral infections were detected; eight positive for CT (2.6%) and one for NG (0.3%). All nine infections were from separate participants, five males and four females, with four recruited from GP clinics, three from universities, and two from sexual health clinics. Further, 6/132 (4.5%) HPV positive participants and 3/180 (1.7%) HPV negative had CT/NG diagnosis (Z score not significant). The six CT/NG participants who were HPV-positive had oral infections with HPV-18, -31, -32, -59, -61, and 62 (HPV-18, -31, and -59 are high-risk HPV types). For association analysis, CT and NG positive samples were pooled into one variable with nine CT/NG positive people. Table 1 summarizes oral HPV positivity and persistence with associations of CT/NG diagnosis. Briefly, six of the nine CT/NG-positive participants were also positive for oral HPV in at least one sample (n = 4 with one oral HPV-positive sample and n = 2 with two HPV-positive samples over time) while three of the participants with CT/NG positive samples were oral HPV-negative. There were no significant associations found between CT/NG positivity and oral HPV positivity and persistence (Table 1). Supplementary Table 1 shows the associations between CT/NG positivity and sexual behaviour and history variables. Of note, a significant association between CT/NG-positive participants and a previous STI diagnosis was found as well as illicit drug use.

Table 1. Oral HPV and CT/NG positivity associations

a Data from the Oral Health Study [Reference Antonsson, de Souza and Wood4].

Discussion

It has long been established that HPV plays a central role in cervical carcinogenesis, but also that additional cervical STIs such as CT and NG could increase the risk of developing cervical cancer [Reference de Abreu, Malaguti and Souza2, Reference Smith, Muñoz and Herrero3]. Here, we explored the associations of CT or NG infections with oral HPV in a primarily random population cohort within the OHS study and observed very low CT/NG positivity. We observed 4.5% of HPV positive and 1.7% HPV negative participants harboured CT/NG in their saliva. These were non-significant associations between oral HPV infection, persistence, and CT or NG infection, albeit acknowledging that this sample size was too small to ascertain associations comprehensively. Research on the persistence of STIs in the oral cavity and associated impact upon HPV is limited. These pilot data, while suggesting that CT and NG have little influence on HPV positivity and persistence, could help inform future larger studies assessing potential associations between oral STIs and oral HPV infections and their outcomes.

Abbreviations

- CT

-

Chlamydia trachomatis

- HPV

-

human papillomavirus

- NG

-

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- OHS

-

the Oral Health Study

- STI

-

sexually transmissible infection

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882300198X.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: A.A., E.T.; Data curation: A.A., E.T.; Funding acquisition: A.A., E.T.; Methodology: A.A., T.A., E.T.; Resources: A.A.; Supervision: A.A., D.W.; Writing – original draft: A.A., E.T.; Writing – review & editing: A.A., D.W., T.A., E.T.; Investigation: D.W., E.T.; Project administration: E.T.; Validation: E.T.

Funding statement

This research was funded by a grant from the Australian Infectious Diseases Research Centre. D.M.W. reports research funding from SpeeDx Pty Ltd. unrelated to the study.

Competing interest

The authors declare that there is no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.