Introduction

In 1990, Rwanda became engulfed in a brutal civil war between the government, dominated by the majority Hutu ethnic group, and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group primarily backed by the minority Tutsi ethnic group. After years of conflict, the major parties signed a peace accord in August 1993. To help implement this agreement, the United Nations (UN) Security Council deployed The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) with a force of 2,548 peacekeepers.Footnote 1 The situation, however, quickly deteriorated. In April 1994, at the start of the genocide, the Hutu government extremists brutally executed ten Belgian UNAMIR peacekeepers on the assumption it would lead to a major drawdown of peacekeeping forces.Footnote 2

While the increasing violence highlighted the urgent need for more peacekeepers, the Hutu government's calculation soon proved true. The UN Security Council (UNSC) mandated that peacekeeper levels be reduced to just 270 (though 503 ultimately remained).Footnote 3 The drawdown was catastrophic, as force commander Roméo Dallaire expected.Footnote 4 Freed from any meaningful external constraints, the genocidal government murdered approximately 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutus.Footnote 5 The violence only abated when the RPF defeated the government militarily. The removal of peacekeepers enabled immense and predictable violence. While Rwanda was exceptional in the scale and speed of the atrocities, it highlights an undertheorised question – when should peacekeepers depart? – and it is not the only location where peacekeepers have withdrawn too soon.Footnote 6 Domestic and international pressure to scale down and ultimately end missions is much more common than pressure to extend them.Footnote 7

What are the moral considerations for when peacekeepers should depart? The departure of peacekeepers from Rwanda was not justified given both the subsequent violence there and the foreseeability of serious violence. Peacekeepers could have saved countless lives. At the same time, peacekeepers cannot stay indefinitely. Peacekeeper deployment has significant economic costs.Footnote 8 Peacekeepers may also infringe on sovereignty and trigger popular resentment. In practice, decisions about peacekeepers’ departure are frequently made on an ad hoc basis or reflect political calculations largely disconnected from ground conditions.

This article develops a theory for when peacekeeping forces should depart that reflects sound normative and empirical considerations. These criteria are just cause, legitimacy, and effectiveness. The account strikes a balance between maintaining peacekeepers for a sufficient duration at suitable levels to achieve a just cause (such as protecting civilians or avoiding a reoccurrence of war), but not past the point that they no longer serve a just cause or do more harm than good. These criteria should aid both scholars and policymakers. Scholars can better understand and morally assess whether past decisions to depart or maintain peacekeepers were justified. Policymakers can better determine when peacekeepers should depart and more systemically glean insights from previous departures.

This article has four sections. The first section contextualises peacekeeping and defines key terms. The second section shows why the existing literature on the ethics of peacekeeping departure remains incomplete. Section three explains what constitutes an ethical exit and unpacks the core criteria of just cause, legitimacy, and effectiveness. The fourth section then applies this framework to a representative case, postconflict Timor-Leste to illustrate how the criteria for determining an ethical peacekeeping exit can work in practice.

Contextualising peacekeeping

International actors can help end or prevent mass atrocities and violent conflicts.Footnote 9 This ability has been coupled with a growing sense of obligation to do so. Most states now explicitly recognise a moral obligation to assist societies suffering from mass killings and other atrocities. About 75 per cent of all states have ratified the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and heads of government unanimously agreed to the World Summit Outcome Document in 2005.Footnote 10 Paragraphs 138–140 state that all countries have a responsibility to prevent and respond to mass atrocities domestically and internationally. It is important to note that a decision to exit a peacekeeping mission is related to, but distinct from, the initial decision of whether to intervene. Situations, where international intervention could be justified, far exceed the number of actual interventions. However, once peacekeepers have been deployed the decision to remove them or leave them in place has distinct ethical considerations that are worthy of consideration in their own right.

Definitions of peacekeeping and related operations are contentious. Paul D. Williams and Alex J. Bellamy, for example, categorise peace operations into six types,Footnote 11 while Thomas G. Weiss argues for a strict distinction between peace operations and humanitarian intervention.Footnote 12 Following Virginia Page Fortna and Lise Morjé Howard's definition of peacekeeping as ‘the deployment of international personnel to help maintain peace and security’,Footnote 13 we use the term to cover a broad range of peace enforcement and peacekeeping activities, but separate it from armed humanitarian intervention such as NATO's in Libya in 2011 or the 2014 intervention in Iraq by the US to protect Yazidis from mass atrocities. Peacekeeping includes deploying international personnel, who are generally armed, to prevent violence, protect individuals during conflict and help enforce peace agreements, or maintain peace and security after conflicts or atrocities have ended. Peacekeepers may use force, including potentially lethal force. Thus, the term includes both formal blue helmet peacekeepers generally overseen by the UN Department of Peace Operations as well as armed police forces that are generally deployed under the auspices of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs. This could include Chapter VI observation and monitoring missions, Chapter VII, and Chapter VIII missions. This is intentionally a broad definition rather than strictly adhering to technical definitions from the UN or other organisations because the principles we advance here should cover all cases of when peacekeepers should withdraw, whether it is a small contingent of mostly unarmed observers, such as UNAMET in East Timor, or major deployments of thousands of troops, such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The increasing use of peacekeepers has coincided with greater scholarly interest. While not universally accepted, scholars have articulated powerful rationales for international intervention to prevent mass killings and other atrocities.Footnote 14 In practical terms, ‘peacekeeping has become one of the main methods the international community uses to resolve civil wars’, prevent mass killing, and stop systemic human rights abuses.Footnote 15 Most peacekeepers are deployed through the UN. Regional organisations, such as the African Union or even multinational military alliances such the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), may occasionally deploy peacekeepers on their own or in conjunction with the UN as envisioned by Chapter VIII of the UN Charter.Footnote 16 While this article focuses on conventional operations aimed at preventing violence, peacekeepers have been tasked with aiding reconstruction, supporting democratisation, protecting human rights, promoting disarmament, demobilising former combatants, and improving governance.Footnote 17

Peacekeeping also imposes costs. While extremely modest compared to the costs of conflict, deploying and maintaining peacekeeping forces is not cheap. More importantly, international troops can risk undermining self-determination and sovereignty of the states where they are stationed. Chapter VII of UN Charter, focused on addressing acts of aggression, threats to peace, and breaches of peace, ‘means sovereignty is not a barrier to Security Council action’.Footnote 18 Sovereignty issues are especially significant when peacekeepers lack consent from the state in which they operate, which can occur under UN Chapter VII peacekeeping. Tension can arise between protecting human rights of at-risk populations and allowing domestic actors to exercise political control over their population.Footnote 19 The risk of popular resentment and cognate abuses of foreign powers typically increase with the length of deployment and the amount of political power peacekeeping and foreign political authorities wield.Footnote 20 Temporarily exercising political authority can be justified if there are good reasons to believe that any alternative would be worse for those at risk of death or other profound human rights abuses.

An ethically sound deployment of peacekeeping requires a compelling rationale. Peacekeeper departure raises similar issues. A peacekeeping mission may still be legally authorised but could ethically depart under certain conditions. Alternatively, a mission may have its legal authorisation revoked but the departure may be unethical. In Rwanda, peacekeepers were legally authorised to leave but their departure caused unacceptable death and destruction.

Current understandings of the ethics of departure remain incomplete

The ethics of peacekeeping in generalFootnote 21 alongside the related notions of jus post bellum (JPB) focused on the ethics of ending war and postwar reconstructionFootnote 22 and jus ex bello Footnote 23 focused on ‘whether a war, once begun, should be brought to an end and if so how’ have generated significant scholarly interest.Footnote 24 Scholars have paid far less attention to what constitutes an ethical or unethical departure for international peacekeepers. Our focus is on when peacekeepers should withdraw, not a general ethics of peacekeeping, or the form the peace should take. We use aspects of just war theory (JWT) in our analysis because of the potential for peacekeepers to engage in violence but not end the conflict through sustained violence or, alternatively, to determine or oversee postconflict reconstruction. Unlike ordinary soldiers, peacekeepers are often impartial, have limited mandates, and rarely seek to engage in combat. Nonetheless, as peacekeepers may use force, including potentially lethal force, to protect civilians or prevent larger conflict, JWT is vital for understanding the ethics of using force. Adopting a JWT framework, however, requires additional clarification about how and to what extent JWT can be applied to when peacekeepers should withdraw.

Jus ad bellum is an appropriate framework for discussions about when peacekeepers should depart for several reasons. First, while peacekeeping operations often take place after conflict, they do not always. Peacekeepers are sometimes deployed preventatively, such as in (now North) Macedonia in the 1990s. Secondly, peacekeepers are sometimes deployed during wars or mass atrocities. In cases such as in the DRC or Rwanda, violence simmers and then ignites, sometimes ferociously. Peacekeepers must decide whether and how to act. In the DRC, peacekeepers engaged in combat even after the conflict officially concluded.Footnote 25 There are, however, differences from war. Unlike war, extensive evidence suggests peacekeepers are generally effective at protecting human rights (as we discuss below). Second, the interests of peacekeepers are usually more multilateral than a state deploying soldiers. Third, and closely related to the previous two, peacekeepers are generally at lower risk than deployed troops of inflicting major destruction for reasons ranging from capabilities to rules of engagement to UN Security Council mandates. For these reasons, we argue an account of when peacekeepers should withdraw is both connected to discussions around jus ad bellum, yet a distinct and important area of inquiry. The ethics of peacekeeper departure deserves elaboration separate from simply applying jus post bellum or jus ex bello principles to peacekeeping. While some considerations of peacekeeping withdrawal coincide with considerations regarding the use of force, ending conflict, or the form of postconflict reconstruction, the circumstances of peacekeeper deployment differ in important ways from the deployment of troops in war.

Instead of jus post bellum or jus ex bello, given the role of peacekeepers, it makes sense to consider the principles regarding when the resort to the use of force is permissible. Jus ad bellum precepts typically include just cause, proportionality, reasonable chance of success, last resort or necessity, right intention, and proper authority.Footnote 26 We focus on and elaborate our views on the first four criteria below because they are the most relevant for peacekeeping. We assume that peacekeepers have the right intention because they have a mandate to support peace.Footnote 27 The right intention overall is distinct from abuses of individual peacekeepers, which we acknowledge can be a significant problem, and discuss below. As the UN or a regional body authorises nearly all operations, proper authority is not a major practical concern for assessing when peacekeepers should withdraw. Even a scholar such as Stefano Recchia who argues that armed humanitarian intervention, when conducted without state consent, must be authorised by a regional or international organisation for it to be legitimate (and not only legal) would thus have little concern about the proper authority of nearly all contemporary peacekeeping operations.Footnote 28

Scholarship on peacekeeping ethics has yet to fully engage with a small but useful literature on peacekeeper departure. Williams and Bellamy note the inherently political nature of exit and serval practical issues related to departure.Footnote 29 Gisela Hirschman has highlighted how determining when peacekeepers should exit creates tension between ‘the normative demand to ensure peace and the pressure for a timely withdrawal of peacekeeping resources.’Footnote 30 David Edelstein outlined the ‘duration dilemma’ whereby popular discontent leads to ‘a choice between ending an intervention too soon or prolonging an increasingly unpopular intervention.’Footnote 31 Richard Caplan's edited volume is perhaps the most comprehensive treatment examining state-building exits in a variety of historical cases and under different administrative structures.Footnote 32 Ralph Wilde looks specifically at ‘Competing Normative Visions of Exit’, but he focuses on exit under different governance and administrative structures rather than the normative and empirical conditions that justify the departure of peacekeepers.Footnote 33 While not solely focused on peacekeeping exist, recent scholarship has also advanced understanding of the legacies of peacekeeping efforts.Footnote 34

The UN itself has examined the issue of peacekeeping exits. The 2001 report, ‘No Exit Without Strategy’, argued for three different understandings of when peacekeepers can depart: complete success, partial success, and failure.Footnote 35 However, as the goals of the report were largely operational, it did not propose clear criteria for when peacekeepers should withdraw. A 2008 UN document outlining peacekeeping principles and guidelines likewise acknowledges the importance of an exit strategy.Footnote 36 While again focused on logistics, it offers some guidance through seven key benchmarks for exit. The first benchmark is straightforward and uncontroversial, ‘The absence of violent conflict and large-scale human rights abuses’ but also includes ‘respect for women's and minority rights’ more generally.Footnote 37 Other benchmarks are even more ambitious. They require successful disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration of armed fighters, ‘restoration of State authority and the resumption of basic services’ nationwide, progress towards the rule of law, creation of domestic institutions able to ‘provide security and maintain public order with civilian oversight and respect for human rights’, the resettlement or return of anyone displaced by conflict, and the establishment of ‘legitimate political institutions following the holding of free and fair elections where women and men have equal rights to vote and seek political office’.Footnote 38 While laudable, these conditions exceed the scope of most peacekeeping missions and the capacity of all of them. As these guidelines cannot offer meaningful ethical or practical guidance, the actual decision to depart risks being ad hoc or based on political expediency. In practice, nearly all states fail to fully uphold these criteria; let alone states where conditions warranted the deployment of international peacekeepers.

More recently, the 2015 High-level Independent Panel on Peacekeeping emphasised working closely with local partners to achieve ‘carefully selected benchmarks’ and the need for peacekeeping exit to be ‘closely planned with national counterparts and regional partners’.Footnote 39 The UN has explored the issues of peacekeeping effectiveness and reform, but not the conditions under which exit can be ethically justified. Despite significant scholarly and policymaker interest, there is still a need for a cogent theory to assess when the exit of peacekeepers is ethically justified.

Ethical exit

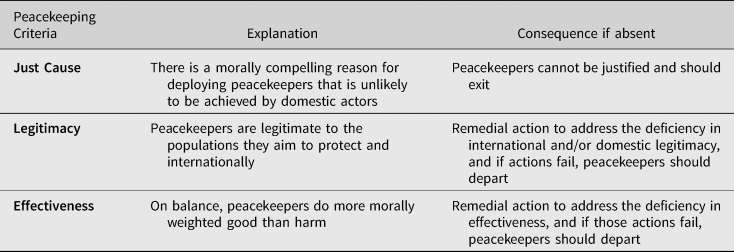

This section provides an overview of what constitutes an ethical exit, before examining the three criteria for determining when peacekeepers can ethically depart in more detail. These criteria are just cause, legitimacy, and effectiveness (Table 1). We focus on moral, not legal, principles.Footnote 40 Just cause means there is a compelling reason for peacekeepers to be deployed. A just cause for international peacekeepers is one that cannot be as effectively achieved by other actors, especially domestic police or military forces. Just causes include preventing the outbreak or reoccurrence of conflict, protecting civilian lives, and preventing or mitigating mass atrocities such as genocide or crimes against humanity both within and beyond the context of war. Second, peacekeepers should be legitimate; both to the populations they aim to protect and internationally. Third, effectiveness means simply that on balance peacekeepers should be expected to do more morally weighted good than harm. This idea closely tracks the JWT precept of proportionality. Suppose that peacekeepers can reasonably be expected to protect a few people's human rights. These goods must be weighed against any relevant harms that peacekeepers are likely to cause. Only if there is a net expected benefit of the relevant goods and harms should peacekeepers remain. This requires making careful, informed forecasts about future events and the consequences of proposed actions, just as decisions based on just war theory, or indeed any policy, do. We discuss this further below.

Table 1. Essential criteria for keeping peacekeepers in place.

So, how do these criteria translate to practice? Peacekeepers should leave if and when there is no just cause. Just cause is a necessary but not sufficient condition for continued deployment. If peacekeepers fail to uphold legitimacy or effectiveness, then remedial action to address the deficiency is required provided it is reasonable to expect that these can be remedied. If these remedial, sustained, good faith efforts fail, then peacekeepers should depart. Constructive changes could include changing the size of the force, modifying its composition, deployment pattern, or strategic approach, providing additional training, and using different technology.

The inverse is also true: peacekeepers should remain if they fulfill these criteria. Our criteria should also apply to the composition or size of the peacekeeping force. Prematurely decreasing peacekeeping forces could undermine the mission's effectiveness, or legitimacy. These are not binary criteria. A small peacekeeping force serving a just cause that is effective and legitimate is better than none, even if it fails to totally realise its goals.

As we are examining peacekeepers that have already been deployed, it is constructive to approach this question by looking at what conditions justify a continued presence. We recognise that departure is often gradual and ‘exit is a process of transition rather than a single moment or event’, but remains a distant and real process.Footnote 41 For example, an exit may be phased out over time or even contingent on certain benchmarks, such as continued stability or achieving certain goals, but provided those are articulated in good faith and envision clear departure date then they would count as an exit. Our proposed criteria for peacekeeper departure account for risks such as exiting too quickly and producing a security vacuum through our just cause and other criteria.Footnote 42 For instance, if peacekeepers depart too quickly, create a power vacuum that then is likely to reignite a violent power struggle, our just cause criteria would still be met and hence peacekeepers should not leave. Peacekeeping missions may change over time, The presence of international armed troops is the key consideration as it is a universal framework for assessing peacekeeper departure under whatever mission happens to be in place.

Just cause

Assessing whether a just cause exists for the deployment of peacekeepers, is an essential first criterion for determining if peacekeepers should exit. Still, just cause alone is insufficient for continued deployment. The idea of a just cause shares some commonalities with the JWT tradition, but it is not identical. Peacekeepers seek to maintain peace whereas just war theorists assess when war is morally permissible. Consequently, there should be a lower bar for a just cause for peacekeepers than for deploying troops for war. War is inherently destructive and harmful; peacekeeping is not. Unlike soldiers participating in war, peacekeepers usually have more limited mandates, are less lethal, rarely instigate conflict, and cause less destruction than soldiers fighting a war. Because the expected harms are both less likely and less severe than war, and because the aggregate benefits are well established (as we discuss below), we argue the just cause threshold for peacekeepers should be lower than war. In other words, the risks of deployment of peacekeepers are generally lower than the risks of deploying soldiers in a traditional war.

Many just war theorists view a just cause as necessary but not sufficient for a just war. Other precepts should also be met, if a war is to be permissible.Footnote 43 For instance, violence should be proportionate. We adopt this view for peacekeepers: a just cause is a necessary but not sufficient for the continued deployment of peacekeepers.

What causes justify the continued deployment of peacekeepers? We contend a just cause exists when there is a good chance that peacekeepers are necessary to protect the physical integrity rights of some innocent individuals in the near future.Footnote 44 We unpack this definition. By in the near future, we mean roughly within the next year. It is useful to limit the time frame of peacekeepers so that intervening states cannot use a just cause as a perpetual excuse to continue deploying troops. Innocent means here someone not liable to defensive harm.Footnote 45 Someone who is liable to defensive harm has forfeited the right against attack to the extent necessary and proportionate to the threat he or she has inflicted. In other words, using violence against a liable attacker can be justified provided it is necessary and proportionate to protect an innocent victim. Civilians, for instance, are rarely liable to defensive harm. Soldiers can also be innocent when fighting for a just cause and have done nothing to forfeit their rights against attack.Footnote 46 Peacekeepers deployed for just reasons and acting within their mandate, similarly, would not be liable to defensive harm. Physical integrity rights are rights against bodily harms, such as murder, rape, torture, and assault. We limit just cause for the retentions of peacekeepers to the protection of physical integrity rights. Otherwise, peacekeepers could be deployed based on a nearly boundless range of issues. To be clear, our approach does not preclude peacekeepers from performing the secondary roles envisioned by multidimensional peacekeeping missions provided that a just cause exists and those activities did not inhibit their ability to meet that just cause. While peacekeepers can assist with democratisation and development efforts, they are usually not experts in these areas and are generally not the best placed to provide that assistance. Moreover, nothing in our framework precludes international assistance for such goals (with or without the presence of peacekeepers).

Requiring peacekeepers to meaningfully protect physical integrity rights within a limited timeframe constrains when a just cause would be met by reasonably limiting the circumstances that warrant their presence. Peacekeepers, however, still have a just cause for deployment in seeking to prevent or mitigate both war and mass atrocities, such as genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes. This latter category is important because in the post-Second World War era around a third of atrocities that claimed at least five thousand civilian lives occurred outside of war.Footnote 47

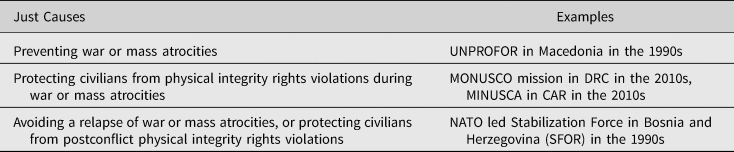

This definition of a just cause allows for continued deployment of peacekeepers before, during and after violent periods.Footnote 48 Peacekeepers are justified in maintaining peace after war. Civil wars frequently reoccur,Footnote 49 and peacekeepers can help mitigate that risk.Footnote 50 While peacekeepers often focus on preventing violence after conflict, there can be other just causes. These include preventing mass atrocities or the outbreak of war. In other words, the just cause criterion is met if there is a serious risk of mass violence in the near future or to decrease the severity of mass atrocities or war (Table 2). International peacekeeping missions in Rwanda, Bosnia, Timor-Leste, Darfur and South Sudan all qualified under this just cause criteria. The situations in Syria and Yemen as of 2022 would also qualify.

Table 2. Examples of just causes for peacekeeping missions.

Even if the original just cause ends, peacekeepers do not necessarily need to depart if another just cause supports their continued deployment. For instance, suppose peacekeepers were originally deployed to help protect civilians during a conflict and the conflict ends with a peace accord. The just cause for the peacekeepers may then shift from protecting lives to maintaining peace. What matters is that there is at least one just cause. However, a mission may exist that no longer serves a just cause as defined above. For instance, the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) has operated for over fifty years. In 1964, the mission was established for a clear just cause of preventing renewed violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. It was effective in that mission and its presence was viewed as legitimate both domestically and internationally. The mission has evolved dramatically since then. In 1974 UNFICYP became actively involved in monitoring troop deployments, maintaining a ceasefire and buffer zone, providing humanitarian assistance, as well as trying to find a diplomatic solution to the dispute between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. In recent years, the situation is different. Notably, there have been basically no deaths related to the conflict since 1974. Experts on the local situation should make the final assessment of the likely effects of continued deployment, withdrawal, or transformation of the existing mission.Footnote 51 If there is a clear indication that international peacekeepers are not necessary to protect physical integrity rights, they should withdraw.Footnote 52 Conversely, Lebanon, another long-standing deployment, poses a clearer risk of serious renewed violence without international peacekeepers. In 2022, the International Crisis Group identified Lebanon as one of ten countries with the most substantial ‘risk of conflict or escalation of violence’.Footnote 53 Thus, peacekeepers are probably justified in remaining because of the threat of violence and their likely role in protecting physical integrity rights, as well as likely meeting the other criteria.

Potential objections to the just cause criteria

When assessing just causes for peacekeeping missions, it is worth addressing two potential objections. One is that the just cause is too permissive. Our just cause condition does not require widespread or systematic physical integrity rights violations for the just cause to be met. A stricter standard would be that only if something like major war crimes or crimes against humanity were likely to occur and peacekeepers could likely prevent these would their continued deployment be permissible. There are several reasons why our standard is not too permissible. One is that peacekeepers may only be able to protect some subset of those targeted by warring factions. A just cause standard that would be met only if peacekeepers could likely prevent any crimes against humanity or major war crimes would be next to impossible to meet in many contexts. Protecting even some innocent people is a morally valuable goal, even if peacekeepers cannot prevent say crimes against humanity entirely. Second, the abuses that peacekeepers aim to protect against may sometimes not constitute crimes against humanity, major war crimes, or genocide. But because the peacekeepers could still protect innocent people from unjust serious harm, their continued deployment would still be justified.

A second objection would turn on fulfillment of any mandate for the permissibility of a peacekeeping mission's continued deployment, rather than physical integrity rights protection. On its face, this is an attractive option. It embodies the commonsensical view that any operation should only withdraw once all of its mission is achieved. This account of a just cause would allow the continued deployment of peacekeepers even if they were not expected to protect any innocent individual from a physical integrity rights violation so long as they were expected to bring other benefits, as stipulated in the mission's mandate. For example, observing elections or promoting gender equality, among others. This position, however, is too permissive. While these goals are undoubtedly important, if credible threats to physical integrity rights are not at stake, other actors can more appropriately achieve these goals. That said, in practical terms, there may be less light between these positions than it seems. This is because campaigns and elections, for instance, where peacekeepers are deployed may turn violent. Peacekeepers can reasonably be expected to help protect innocent people in such situations. To be clear: our view is not that peacekeepers should only be allowed to protect physical integrity rights. We contend that only if physical integrity rights are at stake may they continue to pursue other important goals. Otherwise, efforts to promote democracy, societal change, or development should be left to other actors better situated for these tasks.Footnote 54

Legitimacy

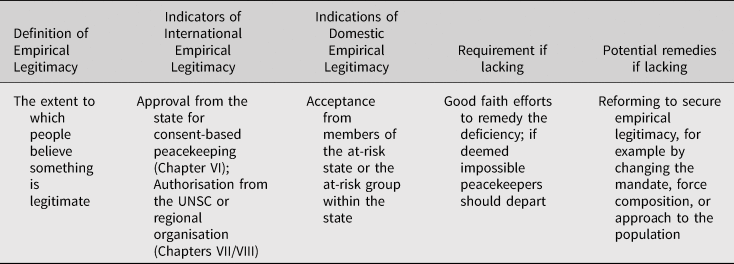

Legitimacy is vital in determining whether ongoing peacekeeping efforts in pursuit of a just cause should continue. Allen Buchanan and Robert Keohane divide legitimacy into two categories, normative and empirical.Footnote 55 Both matter for when peacekeepers should withdraw. Empirical legitimacy means a ‘belief by an actor that a rule or institution ought to be obeyed’ and embodies ‘a subjective quality, relational between actor and institution, and defined by the actor's perception of the institution.’Footnote 56 It can be measured by public opinion polling or observed behaviour. Normative legitimacy assesses to what extent an action, individual, or institution meets certain principles (say, respecting human rights or meeting just war precepts), and is independent of public opinion. Here we concentrate on empirical legitimacy. This is because normative legitimacy reflects the existence of all the other criteria discussed in this article, specifically a just cause, effectiveness, domestic empirical legitimacy, and international empirical legitimacy.

Empirical legitimacy can be assessed domestically and internationally. We argue that a peacekeeping mission requires international and domestic empirical legitimacy and overarching normative legitimacy. If a peacekeeping mission suffers from a deficit of domestic or international empirical legitimacy, reforms should be implemented to attempt to remedy that deficiency before departing (Table 3).

Table 3. The relationship of domestic and international empirical legitimacy to peacekeeping.

International empirical legitimacy

Issues of international empirical legitimacy are complex. Except under rare circumstances, the presence of foreign troops without state consent violates notions of sovereignty predicated on ‘territoriality and the exclusion of external actors from domestic authority structures’.Footnote 57 Sovereignty produces important benefits including space for collective self-determination and preventing unjust invasions and external abuses. Non-intervention in sovereign territory is a core principle of the international system, but it is not absolute and often violated in practice.

International empirical legitimacy should be assessed differently depending on whether the host state consents to the deployment of peacekeepers. Host state consent indicates international legitimacy. This is the logic of the broadly accepted and uncontroversial Chapter VI UN peacekeeping focused on peaceful dispute resolution. Without host state consent, however, peacekeepers can still demonstrate international empirical legitimacy in multiple ways. Approval from the UNSC is sufficient for international empirical legitimacy because their decisions to authorise peacekeeping forces enjoy widespread acceptance within the international system and under international law.Footnote 58 The agreement of the five permanent member states to continue to deploy peacekeepers represents an impressive, if imperfect, international consensus.Footnote 59 The same rationale holds for regional organisations that have been delegated peacekeeping authority under Chapter VIII. Moreover, UN peacekeeping mandates are time bound so there must be ongoing consent for peacekeepers to remain deployed.

The veto power possessed by the five permanent members, however, means the UNSC cannot be a perfect barometer for international empirical legitimacy.Footnote 60 For instance, Russia has directly supported the Assad regime in Syria that committed horrific crimes against humanity and war crimes. The US supports the Saudi Arabian regime accused of war crimes in Yemen. The UNSC can provide international empirical legitimacy, but it is under-inclusive. Consequently, the UNSC cannot be the only way to determine the legitimacy of ongoing peacekeeping operations. International empirical legitimacy, for instance, could be achieved without UNSC approval through a multilateral, regional organisation such as the African Union. In practice, international organisations, including but not exclusively the UN, have emerged ‘as gatekeepers to international legitimacy where the international use of military force is concerned’.Footnote 61 Empirical international legitimacy, however, would be undermined were a large number of countries to challenge the legitimacy of a particular peacekeeping mission.

If a peacekeeping mission suffers from a deficit of international legitimacy, then attempts should be made to remedy that deficit. For example, the peacekeeping mission could seek renewed approval from the initial authorising organisation and perhaps be reconstituted with authorisation from a different body to signify widespread international approval. If those sustained efforts fail, peacekeepers should withdraw. This approach strikes a middle ground between simply accepting the decision of an individual state or states regarding the deployment of peacekeepers and granting only the UNSC the authority to deploy peacekeepers. Ultimately, there is a greater risk of peacekeepers withdrawing prematurely than staying longer than might be necessary. Avoiding a serious risk of genocide or mass killing is more important than potentially undermining sovereignty or causing other harms.

Domestic empirical legitimacy

No matter how legitimate peacekeepers are internationally, peacekeeping missions still require domestic empirical legitimacy as well. This determination could ultimately rest with those who have been and are likely to be at risk of becoming victims.Footnote 62 The composition of this group depends on the situation. When facing atrocities based on ethnicity or religion, it should be members of the at-risk ethnic or religious groups who determine the domestic legitimacy of international peacekeepers. In other circumstances such as interstate war, it would be members of the at-risk nations. Sometimes this determination can be relatively straightforward. For instance, there may be democratic (majority) approval for the mission. In other situations where the majority is not represented by the government, assessing domestic empirical legitimacy can be more difficult. Surveys may also be possible, even in tense or dangerous situations.Footnote 63 Even in difficult circumstances, however, it is often possible to engage with well-regarded leaders that represent at-risk communities such as Nelson Mandela in apartheid South Africa or Xanana Gusmão in Indonesian-occupied East Timor. After the deployment of peacekeepers, other indicators could include whether there are protests against peacekeepers (or the absence thereof). Likewise, direct engagement of peacekeepers with local leaders could potentially help determine the wishes of local communities.Footnote 64 These means of determining support are by not exhaustive and the most constructive approaches which will almost certainly vary depending on the context.

Sometimes democratic support for a peacekeeping mission is impossible because the majority itself seeks to pursue conflict or perpetrate serious human rights abuses. At a minimum, peacekeeping efforts must be legitimate to the parties they seek to aid even if the majority of people in a state disapprove. In Myanmar, for example, state military forces perpetrated widespread ethnic-based violence against the Rohingya minority group. While the violence has prompted widespread international condemnation, there was little domestic pressure from the majority Bamar group. Both the National League for Democracy, its de facto civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and the military leadership that retained immense power, even before seizing full control of the state in February 2021, have actively abetted the violence through denials and obfuscation.Footnote 65 A democratic majority's objections in such cases does not indicate a lack of domestic empirical legitimacy.

Domestic legitimacy for peacekeepers is context specific.Footnote 66 The success of political parties opposed to the continued presence of peacekeepers would generate serious concerns about domestic legitimacy – provided they represent the people whom peacekeepers seek to protect. Large-scale, sustained popular protests against peacekeepers by those peacekeepers aim to protect could likewise signal a domestic legitimacy deficit. Alternatively, if these parties or protests are anti-peacekeepers because they want to act freely in ways likely to harm the groups the peacekeepers seek to protect then this would not suggest a lack of domestic legitimacy. Indeed, it would likely provide additional evidence of a just cause.

Finally, the structure of a peacekeeping mission can have significant implications.Footnote 67 For example, a UN mission might enjoy greater domestic legitimacy if it is seen as more impartial and independent than a regional force. Alternatively, African Union peacekeepers, for example, might be more legitimate to the local population in Africa. While distinct, legitimacy does not operate in isolation from the other criteria. Legitimacy can be increased or decreased based on whether the peacekeeping mission is seen as supporting a just cause and whether it is effective.

Potential objection to the legitimacy criteria

One possible objection to determining the domestic legitimacy of peacekeeping operations based on the support of at-risk populations is that it can unduly empower minority groups over the majority. As Andrew Altman and Christopher Wellman argue in the context of armed humanitarian intervention, ‘that a majority of the victims welcomes the intervention, then one thereby empowers the group's majority – whenever they so choose –to force the minority to remain in a position where their human rights are vulnerable to violation. It seems dubious to hold that a group has this type of normative dominion over its members.’Footnote 68 This objection must be weighed against other important considerations, most notably the tremendous harm that minority groups could face from targeted violence. Furthermore, local populations have information that cannot easily be obtained by outside actors.Footnote 69 Indications of domestic empirical legitimacy are an important source of information on the effectiveness of peacekeepers or if peacekeepers are engaged in inappropriate ehavior. If the majority of the population that the peacekeepers seek to protect wants them to leave, it reflects a lack of domestic legitimacy.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness is only relevant when a just cause exists. Without a just cause, the continued deployment of peacekeepers cannot be justified. Effectiveness examines whether peacekeepers can achieve their goals, for example, stopping the recurrence of war, preventing atrocities, or protecting physical integrity rights. It is an independent consideration because a peacekeeping mission may serve a just cause but fail to adequately contribute to it. As the UN itself has recognised, a mission could be ineffective for various reasons such as poor design, understaffing, or insufficient resources.Footnote 70 The composition of a mission also matters.Footnote 71 If a peacekeeping mission causes more morally weighted harm than good, it should likewise be remedied and if that proves impossible discontinued.

Proportionality in JWT is instructive here. It roughly requires that the likely relevant goods outweigh the likely relevant harms.Footnote 72 But what counts as relevant? While fully exploring this question lies beyond the scope of this article, it is sufficient to note that we avoid the extreme of including all goods and harms. We follow Hurka in proposing that only actions related to the just cause of the peacekeepers should count as relevant goods, but that all harms should count.Footnote 73 Jeff McMahan and Robert McKim argue there are two types of just causes, sufficient and contributing,Footnote 74 and these are relevant for proportionality calculations.Footnote 75 A sufficient just cause is one where it alone would qualify as a just cause for war. A contributing just cause cannot itself qualify as the just cause criterion; nevertheless, it can be a legitimate war aim when there is at least one sufficient just cause. Self-defence is a sufficient just cause, while a contributing just cause could be disarming an adversary who is likely to wrongly use such weapons in the future. Relevant harms include those typically considered by just war theorists such as unintended but foreseeable harms to innocents when a peacekeeper engages an enemy. Relevant goods that should be excluded are, for instance, if a poor country earns significant revenue from deploying its peacekeepers because it is neither a sufficient nor a contributing just cause for deploying peacekeepers. Second order negative effects, however, should factor into proportionality calculations. For example, if a war results in a famine or the spread of a disease, but is not the direct effect of soldiers fighting, these secondary effects should count. A UN peacekeeper shooting someone by mistake is a relevant harm. Likewise, peacekeeping missions can have both positive and negative economic consequences.Footnote 76 Food costs, for instance, may increase from peacekeepers increasing demand, thereby decreasing food availability for local populations as well as other harms peacekeepers could commit such as sexual abuse must be counted.Footnote 77

To meet the effectiveness criteria, peacekeepers should be well positioned to fulfill their mandate. Peacekeepers often offer advantages over domestic security actors because they are not parties to a conflict, often strive to maintain impartiality, and can work independently of domestic political actors. Under certain circumstances, peacekeepers may also engage with local security actors to try to better protect civilians or prevent conflict.Footnote 78 However, if domestic actors could perform the same role – while upholding at least the same level of respect for human rights – then peacekeepers would not be the best actors. First, peacekeepers that lack host-state consent impose sovereignty costs. Second, all things being equal, it is preferable to build a domestic police's institutional capacity when possible. Peacekeepers will eventually depart. Domestic police need to develop relationships with local communities to build trust and knowledge. Third, peacekeepers are significantly more expensive than local police due to the greater costs of deployment and maintenance.

Peacekeeping costs should be placed in a broader context. While expensive relative to domestic police forces, they are very cost effective compared to the costs of renewed conflict.Footnote 79 For instance, Kofi Annan estimates that deploying sufficient peacekeepers in Rwanda to prevent the genocide would have cost about $500 million annually. This amount pales in comparison with the $4.5 billion that the international actors spent on post-genocide humanitarian aid,Footnote 80 and this is to say nothing of the human suffering and lost economic output resulting from the death, displacement, and destruction.

Effectiveness challenges are intrinsic to peacekeeping because even the best designed peacekeeping mission raises significant and complex principal-agent incentive issues. These principal-agent problems stem from the extensive delegation required between UN headquarters (or various capital cities) and peacekeepers on the ground, the immense coordination issues, the often-divided goals and interests of the principals, such as the UN secretariat and key nations, and the difficulty of implementing robust monitoring regimes, particularly in conflict-prone and remote areas. The delegation from the international to the local level involves high agency and transaction costs. The principal's goals can be unclear and conflicting, control mechanisms are often weak, and information disparities among parties are high. To prevent sexual assault and other abuses of power and ensure their effectiveness more generally, peacekeeping missions require a robust monitoring regime backed by powerful sanctions to deter bad behaviour. Peacekeeper training and selection are equally essential. While international peacekeeping inevitably generates principal-agent issues, ‘norms can embed the interests of the principal allowing the agent to significantly reduce the problem.’Footnote 81 Peacekeepers must internalise the importance of protecting vulnerable populations and robust accountability mechanisms need to be established to deter inappropriate behaviour.

Potential objection to effectiveness criteria

One might object that peacekeeping missions are generally ineffective and that consequently, they cannot meet the effectiveness standard.Footnote 82 The literature, however, suggests that peacekeeping can be largely effective in terms of prevention, during conflicts and atrocities, and the postconflict or postatrocity period. Both recent scholarshipFootnote 83 and detailed reviews of the existing literature have highlighted the effectiveness of peacekeepers in saving lives in numerous ways.Footnote 84 Peacekeeping can help prevent conflict from starting or escalating, help end conflict, and help prevent it from reoccurring. Moreover, it also suggests that the criteria we outline are particularly useful as ensuring that peacekeeping missions are adequately staffed and equipped would further increase their effectiveness and save additional lives.

Peacekeeping can have negative effects too. Rogue peacekeepers can directly harm vulnerable people including perpetrating sexual abuse and exploitation.Footnote 85 Peacekeepers were responsible for the cholera outbreak in Haiti that caused over nine thousand deaths.Footnote 86 Peacekeepers without a civilian protection mandate may increase rebel attacks.Footnote 87 These findings show that peacekeepers require appropriate mandates, extensive training, and effective accountability mechanisms. On balance, however, an objection that peacekeepers cannot be effective fails.

For the theory of when peacekeepers should withdraw to be credible, it is necessary to be able to forecast whether violence is likely to occur and whether the precepts discussed here are likely to be met. While we do not have space to discuss how these forecasts should be made, we note that forecasting is both currently feasible and steadily improving.Footnote 88

Forecasting has already been demonstrated to be feasible for peacekeeping missions.Footnote 89 For example, in 2019, the UNSC paused the planned drawdown of UNAMID peacekeeping forces in DarfurFootnote 90 after satellite imagery and other evidence suggested force withdrawal could lead to widespread death and destruction by government-backed forces.Footnote 91 Those peacekeepers were subsequently withdrawn in 2021, despite continued serious concerns about renewed conflict. Unfortunately, as predicted, violence has increased since the peacekeepers departed.Footnote 92 In sum, each of the three criteria is necessary and jointly sufficient for peacekeepers to remain morally permissibly.

The departure framework in practical application: Illustrations from Timor-Leste (1998–2012)

UN peacekeeping in Timor-Leste between 1998 and 2012 demonstrates how the departure framework can be applied to a peacekeeping mission. Timor-Leste's experience with international peacekeepers is particularly useful because, at different points in time, intentional involvement ranged from minimalist to extremely comprehensive, and engagement in Timor-Leste has highlighted the need to remedy an ineffective peacekeeping mission, an unjustified exit, and ultimately an ethical exit.

East Timor officially became a colony of Portugal in 1702. It remained so until domestic events in Portugal triggered a rapid and haphazard process of decolonisation in the mid-1970s, including in East Timor. Elections resulted in a majority for the FRETILIN party. Portugal departed in August 1975 and FRETILIN declared independence that November. Shortly thereafter Indonesia invaded and occupied East Timor in violation of international law. The devastation was immense. Roughly 200,000 people died due to Indonesia's occupation – a staggering amount in a country of less than a million people.Footnote 93

Despite the occupation's intensity, a vibrant resistance movement emerged. While the annexation was successful in practical terms, it never achieved legitimacy within East Timor or internationally. In 1998, Indonesian President B. J. Habibie undertook a new approach to East Timor. After extensive negotiations, Indonesia, Portugal, and the UN agreed on a referendum. Timorese voters were given a choice between autonomy within Indonesia and independence in August 1999. The UN Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) would conduct the referendum. While not a peacekeeping mission in a strict sense under UN regulations as it was overseen by the Department of Political Affairs, it nevertheless raises the issue as it involves the deployment of international armed personnel with the potential to use lethal force. Through Resolution 1246 (1999) the UNSC unanimously agreed to deploy up to 280 civilian police officers (ostensibly to advise the Indonesian police forces) and fifty international military liaisons.Footnote 94 Yet, the UN mission was not empowered or able to maintain order. However, it did include a mandate ‘for ensuring the freedom of all political and other non-governmental organizations to carry out their activities freely’.Footnote 95 Despite clear indications that intimidation and violence risked compromising the referendum's integrity, ‘the agreement placed sole responsibility for maintaining law and order during the referendum’ with Indonesian security forces.Footnote 96 UNAMET's effectiveness was further hampered by insufficient resources and targeted violence towards UN staff by pro-Indonesian forces.Footnote 97 These concerns proved well founded. Indonesian military-backed militias undertook an intimidation campaign against the pro-independence side. Ultimately, over 98 per cent of eligible voters participated with over 78 per cent supporting independence. In response, pro-integrationist militias unleashed a wave of violence across the country. Most UNAMET personnel were quickly relocated to the capital, and many were evacuated entirely.Footnote 98 Ultimately, ‘post referendum violence left hundreds dead, almost the entire population displaced, and 70 percent of buildings in ruins.’Footnote 99

The bloodshed surrounding the 1999 referendum illustrates the stark consequences of an ineffective effort to maintain order and prevent violence. While UNAMET had a just cause and enjoyed domestic and international legitimacy, it failed to uphold the effectiveness criteria as their presence did little to deter violence before or after the referendum. Under our criteria, the UN mission would have been ethically required to bolster its capacity to protect the civilian population from violence which was foreseeable and even expected by UN staff on the ground.Footnote 100 The ability of a larger and more empowered peacekeeping mission to quickly end the violence after the referendum shows how a more robust force could have prevented violence from occurring at all.Footnote 101

Widespread post-referendum violence brought international condemnation and eventually a more robust peacekeeping presence in mid-September 1999.Footnote 102 In October, UN Resolution 1272 established the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) and vested it with sovereignty over the territory during the transition to independence. UNTAET not only had a mandate ‘to provide security and maintain law and order throughout the territory of East Timor’, it had enough international peacekeeping forces to do so.Footnote 103 The UNSC authorised the deployment of up to 8,950 troops alongside two hundred military observers. After free democratic elections and a domestic-led constitution drafting process, Timor-Leste emerged from UN trusteeship to full independence in 2002.

Timor-Leste, however, still faced profound security challenges. The powerful political factions that banded together during the independence struggle became increasingly fractured and prone to conflict. While peacekeepers remained, these conflicts never became violent. The country enjoyed peace and stability under UNTAET (1999–2002) and its successor mission, the UN Mission of Support in East Timor (2002–05).Footnote 104 Peacekeepers clearly fulfilled the key criteria. Both of these missions effectively served the just cause of preventing the reoccurrence of violence and were recognised as legitimate both domestically and internationally.

The successor mission from 20 May 2005 to 20 May 2006, the UN Office in Timor-Leste (UNOTIL), continued to support peace, but at a significantly reduced level. UNOTIL was seen as a precursor to a rapid departure of peacekeepers. UNOTIL marked a departure as it was a decision to start the process of peacekeeper exit, but no mutually agreed plan with domestic officials or well-considered benchmarks existed. The Secretary General originally proposed a small security force of 144 peacekeepers for UNOTIL (which would have still been a significant decrease from the 310 troops that were stationed in Timor-Leste).Footnote 105 That proposal, however, was rejected by the UNSC after Australia, the UK, and the US successful argued even the limited force was unnecessary.Footnote 106 In the end, UNOTIL's security portfolio consisted of only 40 police advisors and 35 border patrol advisers, of which 15 could be military advisers.Footnote 107 While the UNSC believed that the peacekeeping mission could be drastically scaled down or even eliminated without major consequences, contemporary evidence suggested internal violence remained a very real possibility. Even the UN Secretary General recognised events that indicated a looming threat of violence, but ‘invariably reported them in a way that suggested that they had ended in the resolution of the differences underlying them’.Footnote 108 For their part, Timorese political leaders had not asked peacekeepers to depart and later explicitly asked for them to return.Footnote 109 In other words, a just cause for deployment existed, albeit now the prevention of conflict between rival domestic political factions rather preventing violence from Indonesian-backed forces, and peacekeepers still enjoyed legitimacy both domestically and internationally. The negative consequences of scaling down and dramatically reducing the peacekeeping mission's effectiveness were immense and foreseeable.

This rapid, haphazard departure exemplifies the risks associated with ‘premature exit of international security forces’.Footnote 110 The outbreak of political violence in May 2006 led to 36 deaths, the displacement of 150,000 people, and the destruction of over 1,600 homes.Footnote 111 The proximate cause was a domestic military dispute between competing regional factions. The deeper reasons are complex but fundamentally reflect a clash between domestic political elites. The escalating violence was only defused by the return of international peacekeeping troops in August 2006.Footnote 112 Violence would have been highly unlikely with a larger, more effective peacekeeping force.

The UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) commenced in August 2006 and lasted through December 2012. UNMIT authorised ‘up to 1,608 police personnel, and an initial component of up to 34 military liaison and staff officers’.Footnote 113 It possessed the capacity and the mandate necessary to maintain order. Under UNMIT, international peacekeepers upheld the criteria of just cause, domestic and international legitimacy, and effectiveness until their departure in 2012. The international presence stabilised and helped prevent any mass violence, even during 2008 when simultaneous assassination attempts targeted the president and the prime minister. While it might seem that the troops could have departed earlier without significant risk, widespread fears of electoral violence persisted throughout 2012.Footnote 114 Likewise, credible concerns remained about the ability of the local police to maintain order.Footnote 115 UNMIT peacekeepers still had a just cause in preventing the outbreak of violence and they were effective in preventing that violence. As peacekeepers were authorised by the UNSC and accepted as legitimate by the local population, UNMIT itself retained both domestic and international legitimacy throughout its tenure. Unlike the previous peacekeeper departure, UNMIT's departure featured clear timelines and ‘mutually agreed criteria’ that were acceptable to both international and Timorese officials.Footnote 116 This framework was largely followed in practice, which managed expectations and provided sufficient lead time for a successful, rather than destabilising, transition.Footnote 117 When departures from the agreed framework occurred, most notably the early handover of policing to local authorities in 2011, they were due to requests from Timor-Leste's democratically elected government.

Timor-Leste illustrates how the departure framework can work in practice. It shows it is feasible based on existing information to adjust the scale of the mission as well as determine when departure is ethically justified. These determinations can be made both during the regular mandate review processes as the UNSC as well as in response to events on the ground. These determinations may well be challenging but given the amount of investment inherent in a peacekeeping commitment, there is good reason to believe they are able, or at least should be able, to make these determinations.

Conclusion

As peacekeeping has emerged as a major feature of the international order, debates over when to deploy international peacekeepers have generated immense scholarly interest. In contrast, the normative considerations surrounding when peacekeepers can ethically exit have received far less attention. Yet, these are also immensely important decisions. If peacekeepers depart too soon, there could be a risk of catastrophic violence, mass killing, and large-scale human rights abuses. As a practical matter, peacekeepers are far more likely to depart too soon. Nevertheless, it is also important to recognise that leaving peacekeepers in place too long unjustifiably impinges on sovereignty, and self-determination, and imposes economic costs. Put simply, when peacekeepers depart can have a large impact on the political, economic, and social power structures within a society.

This article seeks to help fill this gap by offering a normative framework to determine when the departure of peacekeepers is ethically justified. Robust debates will likely, and indeed should, continue regarding whether the specific criteria of just cause, effectiveness, and legitimacy are upheld in particular instances. A framework outlining the criteria for departure helps structure the debate and ensures that these major decisions, which have immense stakes, rest on solid normative foundations rather than ad hoc considerations or rationalised political expediency. While each peacekeeping operation will invariably face unique circumstances, a framework that can be applied across different settings is not only possible but crucial to prevent loss of life and profound violations of physical integrity rights.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Vanessa Newby, Meghan Campbell, and Johannes Kniess for their feedback on earlier drafts of this article. They also appreciate the constructive comments of the four anonymous peer reviewers and the editors of the journal.

Dr Eamon Aloyo is an Assistant Professor at Leiden University. Author's email: e.t.aloyo@fgga.leidenuniv.nl

Dr Geoffrey Swenson is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in International Politics at City, University of London. He is the author of Contending Orders: Legal Pluralism and the Rule of Law (Oxford University Press, 2022). Author's email: Geoffrey.Swenson@city.ac.uk