Introduction

Academic research on civil-military relations has traditionally focused on determinants of civilian control over the armed forces, enshrined by the so-called civil-military problematique, that is ‘to reconcile a military strong enough to do anything the civilians ask them to do with a military subordinate enough to do only what civilians authorize them to do’.Footnote 1 This literature has often assumed that dangers for democracy mainly emanate from the military's political power and that, if given the opportunity, the armed forces tend to ‘push’ their way towards role expansion, an increase of their autonomy or even, under certain conditions, their involvement in politics. The propensity to push stems both from the informational advantage that the military has over the civilians and from the civilians’ inability to systematically assess an uncertain environment.Footnote 2 Civilian governments, on the other hand, are implicitly expected to reduce the military's political power when they are able to do so or should such power have increased excessively.Footnote 3

Less is known about the seemingly counterintuitive, but widespread empirical phenomenon of civilian governments that are expanding military roles or deferring political authority to the armed forces to an extent that potentially weakens civilian control of the armed forces.Footnote 4 To illustrate, political leaders in Western European countries – such as Belgium and France – have relied on soldiers in the fight against domestic terrorism since 2015 to demonstrate their strength and to shore up their popularity.Footnote 5 In the United States, former President Trump tried to pull the military into a law enforcement role, which the US military leadership apparently resisted.Footnote 6 Along similar lines, several Latin American countries such as Brazil or Mexico have increasingly deployed soldiers in police roles to counter violence and crime. This has not only raised concerns regarding the military's supposed inadequacy for law enforcement tasks, but also the possible return of undue political influence in a region once dominated by military regimes. These fears were further exacerbated by governments that have expanded military powers as a reaction to social unrest.Footnote 7 Trying to pull the military into political disputes can go as far as to backfire: the Bolivian military's insubordination in resisting the president's demand to repress anti-government protests ultimately contributed to Evo Morales's ouster in 2019.Footnote 8 These are all instances of pulling, defined as politicians ordering the military to perform missions that do not belong to their usual operational profile.Footnote 9

Notwithstanding the seeming relevance of this phenomenon, we know little about its dynamics: which shapes pulling can take; what happens after pulling occurs; and much less about the conditions for the military's reactions to pulling. Theories about civilian control seem ill equipped to shed light on these issues because of their traditional focus on specific determinants of civil-military equilibria and because of their over-emphasis on the military's desire to push for more power. In this article, we adopt an inductive approach and develop a framework to better understand the dynamics of pulling and its implications for civil-military relations. We argue that, once pulling starts, the reactions of the military leadership to pulling crucially depend on their role conceptions. Role conception is ‘a shared view, shared within one service or shared by all the services, regarding the proper purpose of the military organization and of military power in international relations’.Footnote 10 As the military adapts to the demands of the pulling move, for instance by changing doctrine and training, its role conceptions slowly change and thus affect the military's reaction to future instances of pulling.Footnote 11

We focus on role conceptions about missions, and on how the military understands its role vis-à-vis politicians. For analytical clarity, we identify three distinct phases in which pulling occurs, which we see as empirically intertwined and potentially mutually reinforcing. In a first phase, we identify pulling moves by politicians and distinguish between two types: political pulling and operational pulling. A ‘political pulling’ move entails demands on the military to publicly back the executive against other government branches or to clamp down on political protests. Political pulling implies an intention to draw the military into partisan conflicts. The other kind of pulling move we focus on is operational pulling. Compared to political pulling, this is a less politically loaded process as it means to let the military carry out missions that they usually do not perform. Depending on how the military's role conceptions harmonise with such an unprecedented operational experience, however, operational pulling can yield significant changes in civil-military relations.Footnote 12

In a second phase, we expect the military to respond to pulling in different ways, ranging from open resistance to unconditional compliance. We argue that the ways in which the armed forces respond to politicians’ demands primarily depend on two distinct role conceptions, namely the views about the military as a non-partisan institution and those about the crucial core missions of the military. In a third phase, we expect a shift in role conceptions if there are long term or significant alterations to the armed forces’ predominant tasks and missions. If certain missions – here understood as ‘specific tasks’Footnote 13 – are carried out to such an extent that they shape the military's role – understood as a ‘broad and enduring purpose’Footnote 14 – armed forces might slowly change their role conceptions accordingly. Operational pulling moves can trigger the military's desire to shape political conditions of their deployments and thus erode non-partisan role conceptions.

We illustrate our framework using two cases, France and Brazil. French politicians have performed operational pulling after the terrorist attacks in France after 2015, to which the military responded very reluctantly. By 2020, the French military seems to have progressively accepted its new role and some signals suggest a relative increase in the involvement of the military in the political sphere, even if civilian control still holds strong. Brazilian governments have significantly increased operational pulling from 2010, as they broadened the scope of internal ‘Guaranteeing Law and Order’ operations. As this reinforced the Brazilian military's traditional inclination to get involved in politics, the generals soon embraced the possibilities of increasing their power. Individual officers have taken over the political roles they were tasked with in instances of political pulling, and some even joined the government while still being on active duty. Taken together, our illustrative case studies suggest that pulling and pushing dynamics are not unidirectional but mutually reinforcing processes that, once launched, might be difficult to stop.

The remainder of this article is divided into four parts. In a theory section, we discuss previous research and develop our exploratory analytical framework. Second, we briefly discuss and present our cases. Third, we delve into our case discussion. Lastly, we draw conclusions from our findings and suggest avenues for further research.

Previous research about ‘pulling’

Research on civil-military relations (CMR) typically focuses on the interactions between actors or institutions of the political system and the military.Footnote 15 Hence, the central question of research on CMR has traditionally been: ‘who guards the guardians and how?’.Footnote 16 The CMR literature has predominantly studied different states’ ability to successfully reconcile the civil-military problematique, which led to a striking bifurcation: on the one hand, studies theorising about countries that do have civilian control over their military and, on the other hand, countries struggling with establishing norms of civilian supremacy.Footnote 17 In large parts, this research is wedded to concepts that were developed on Western liberal democracies and as such struggle to grasp different models of civilian control.Footnote 18

Taken together, most of these approaches share at least an implicit assumption that militaries as rational actors would gladly seize opportunities to expand their power. They would generally tend to ‘push’ their way into politics, demand more resources or autonomy, and eventually contest political decisions that stand against their corporate interests.Footnote 19 Particularly, research on civil-military relations in countries with a history of military meddling in politics has taken the generals’ ‘push’ for political power for granted, and typically equates civilian control and the military's compliance with civilian orders with healthy civil-military relations. Some have argued that the armed forces typically engage in a ‘strategic exchange’Footnote 20 with governments when being asked to perform undesired missions: they can make their compliance to orders conditional upon politicians meeting their demands, for instance regarding military budgets, equipment, or the legal framework of internal operations.Footnote 21 Governments making themselves dependent upon the military for the provision of essential state services thus run the risk of increasing the military's bargaining power. In extreme cases, armed forces can threaten governments with ‘acts of omission’Footnote 22 in case their demands are not met.

To develop our argument, we contribute to recent efforts to understand the phenomenon that political leaders are sometimes wilfully delegating political responsibilities to the military.Footnote 23 We also build on several debates that took place in the 1990s about a crisis in US civil-military relations.Footnote 24 Then, Edward M. Luttwak and Russell F. Weigley identified a certain degree of military intransigency to make sense of the resistance to pulling, while others thought it had more to do with disagreement among civilians.Footnote 25 Within that debate, US military personnel's acceptance of new missions tracked closely with their beliefs about whether society and political leaders supported these missions. Unlike that debate, however, we are interested in understanding – at a higher level of abstraction – the conditions under which military personnel may align (or not) to pulling. A more fine-grained analysis of push-and pull-mechanisms is necessary, bringing the significance of military role conceptions to the fore.

The assumed dominance of the military's predisposition to ‘push’ its way into political decision-making power has obscured the phenomenon of politicians – in both democracies and autocracies – ‘pulling’ the military into politics. At times, fulfilling these missions is against the military's corporate interests. Many recent crises in civil-military relations thus did not originate in a lack of civilian oversight or in flawed institutions of civilian control. On the contrary, politicians created problematic situations precisely because civilian control was more or less firmly established: this allowed them to pull the military into roles and tasks the latter were reluctant to take on. Yet, the variation in reactions to these demands we briefly depicted in the introduction is neither explained by the CMR literature's focus on the level of civilian control, nor by treating the armed forces as a black box that invariably contests political decision-making. Moreover, traditional theories of civilian control have focused on determinants of civilian control, assumed and understood as a relatively static equilibrium.Footnote 26 However, in order to understand how those interactions unfold, we need to develop more dynamic theories and concepts.Footnote 27 We therefore focus on assessing the military's reactions to being pulled into missions within the broader context of a civil-military equilibrium. Our analytical framework aims to provide tools for understanding the determinants of armed forces’ reactions and highlights the importance of the military's role conceptions.

Unpacking ‘pulling’

We propose an analytical framework to improve our understanding of the mechanism of ‘pulling’. We first introduce the two key components of the framework, namely: operational and political pulling as well as the military's role conceptions. Then, we present the three phases in which pulling occurs and explain how and why role conceptions matter therein.

Political and operational pulling moves

In our conceptualisation, pulling only occurs if militaries need to act outside their regular roles when following politicians’ demands. Among all possible pulling moves, we identify two types: political pulling and operational pulling.

A political pulling move is rather blatant and has obvious implications for civilian control and politics, as it entails giving the military a more or less explicit task of getting involved in partisan politics. Political pulling is thus highly problematic under any circumstances, as it intentionally aims to use the armed forces for political or electoral benefit.Footnote 28 If governments ask the military for support in political crises or the repression of large-scale anti-government protests, military leaders need to decide whether to uphold the principle of civilian control at all costs, even if this would come with risks for the military as an institution or democracy as a whole. In particularly acute constitutional crises, it has been argued that militaries make political judgements: in their decision to obey orders or not, they consider the likelihood of being held accountable for violent repression by the following government. If chances for this are higher than for being punished by an already weakened government, military leaders arguably tend to prefer to remain in the barracks.Footnote 29 Some Latin American militaries’ preference to avoid clamping down on protests has been seen as a sign for a ‘major shift in the militaries’ understanding of how they fit into their societies’.Footnote 30 Once more, this underlines the significance of role conceptions – which are shaped by both ideational factors and operational experiences – as determining factor in the military's behaviour.

An operational pulling move entails that the military is asked to perform missions that are outside its usual operational spectrum. This is not necessarily problematic for civil-military relations. As long as these missions are not unconstitutional, civilian governments have to be able to give the armed forces a new task. Assuming civilian control over the armed forces, military leaders would then have to accept these new missions. Operational pulling moves are apparently innocuous but may have equally damaging consequences for civilian control like political pulling. Similar to political pulling, governments order the armed forces to perform missions that fall outside their usual remit – and thus have the potential to change military role conceptions. It is well known that the operational experience in different types of missions can have consequences for civil-military relations.Footnote 31 Depending on the type of mission, there may be indirect, potential political consequences. For instance, we expect that the military's adjustment to an unprecedented involvement in internal public security would draw the military leadership's attention to the circumstances of their deployment – and thus pave the way for an increase in the generals’ desire to become politically involved. Our expectation builds on previous literature assuming that internal military missions arguably open a ‘window of opportunity’,Footnote 32 which armed forces may exploit in order to increase their political clout.Footnote 33

Taken together, the meaning of pulling varies from case to case as certain militaries might be accustomed to tasks that are unthinkable for other armed forces. The military's reactions to different forms of pulling fundamentally depend on how appropriate they consider demands by politicians. Operational and political pulling are two broad, intrinsically linked categories that capture the empirical phenomenon we are interested in. Our focus on role conceptions shall provide an analytical framework for the military's reactions to these types of pulling.

Role conceptions as driver of reactions to pulling moves

In order to better understand the military's reactions to pulling, we build on previous research on role conception. The concept was first introduced by Kal J. Holsti, then updated by Ulrich Krotz and used by both authors to capture national role conception and foreign policy.Footnote 34 Pascal Vennesson et al. applied role conception as a concept to the military and define it as ‘a shared view, shared with one service or shared by all the services by its history and memory and is used to socialize military personnel’.Footnote 35 While Vennesson et al. acknowledge that it may change and evolve over time, it is not a transient attitude.Footnote 36 The underlying idea of role conception is that military organisations will differ in asserting and defining their own role. A given military's role conception is conceived to affect policy, shape goals and actions, and filter policy options, making some feasible and others unconceivable.

We adopt the concept of the military's role conception and innovate it in two ways. First, for Vennesson et al. it is mainly history and memory that shape role conception. Yet, we contend that several other factors shape role conceptions about missions and relation to politicians.Footnote 37 Role conception is not only shaped by history and memory but also by military culture and is embedded in the broader debate about military professionalism. In comparison with other neighbouring concepts, it has the advantage of being more precise and narrow.Footnote 38 Another important factor that may shape role conception is a heritage of pulling. Some militaries may have historical experience of being pulled into some missions but have shifted their role conceptions in the sense that they do not wish to return to these previous roles. For instance, armed forces that once were involved in military regimes might have tried to turn the page on their past and struggled to develop role conceptions that are more suitable for democracies.Footnote 39 Certain forms of pulling, particularly political pulling, could damage such efforts. In these cases, pulling becomes a litmus test for the resilience of recently developed role conceptions and democratisation processes. Finally, modes of recruitment may also play a role in shaping role conceptions, particularly by bridging the civil-military gap and, potentially, the type of response to pulling. In the short term, role conceptions are also shaped by the perceived cost of being pulled as there are also risks from the military's perspective. For example, armed forces worried about their prestige might see internal missions as potentially risky for their good standing among the population. When public security missions lead to victims among the population, the armed forces’ image might suffer. Moreover, prolonged engagements in fighting organised crime also carry the risks of soldiers becoming corrupted by the financial possibilities of criminal organisations.Footnote 40 Second, we try to make the concept of role conception even more precise by focusing on two distinct facets: those about missions and those about the military's political role. Vennesson et al. focused the concept on missions and the use of force, the latter being very much related to the political role since it is ultimately the potential threat to enforce their political will that defines the military's relation with the government. Our focus is on more subtle ways of making the military's voice heard in politics as well as about disentangling distinct role conceptions within the armed forces.

What constitutes role conceptions for today's militaries?

While armed forces’ primary goal has traditionally been defending their country against external threats, we do acknowledge that militaries today do much more and much else. A helpful distinction is to be made as military organisations develop role conceptions about both their means and aims. To illustrate, defending the country is still among the main aims of most military organisations but the means to achieve those aims can be very varied – for instance, expeditionary operations ranging from counterterrorism to counterinsurgency to territorial defence. New operational experiences mostly contrast with role conceptions about means and about the military's appropriate relation to politics. Role conceptions about core missions are intricately linked to the operational pulling moves depicted above. By contrast, role conceptions about the military as a non-partisan institution are key to understanding the likely reaction to political pulling. In situations of political pulling, the military needs to decide whether they give more weight to respecting the principle of civilian control – and thus obeying potentially problematic orders – or the principle of being a state institution that does not interfere in partisan politics. We would expect militaries that understand their role as strictly non-partisan to react more reluctantly to political pulling than armed forces with a less non-partisan role conception.

Regarding operational pulling, it is not a problem, per se, when governments give their armed forces new tasks. Some deployments might demand changes in doctrine and training, which ultimately affects (at least parts of) the military's role conception. Lengthy processes of drafting doctrine and eventually costly efforts to reshape military training could thus be understood as indicators for the military's acceptance of a role that derived from these new missions. Depending on their pre-existing role conceptions, militaries might be reluctant to adapt to new operational profiles and make their compliance conditional upon politicians meeting their demands with respect to legal frameworks or other matters of the military's corporate interest. In the long run, such conditional adaptation to operational pulling increases the likelihood of shaping the military's role conceptions regarding its position vis-à-vis civilian politicians and about appropriate levels of political involvement. Also, tasking the military with new missions (operational pulling) may make a potential political pulling more likely in the future, especially if these missions are being carried out over a long time and if they represent a fracture from the past. Even missions that are seemingly unproblematic, for instance a prolonged engagement in humanitarian assistance, might lead to mission creep that can slowly expand and politicise military tasks.

Three phases of pulling

In a first phase, politicians start an operational or political pulling move by asking the military to become involved in tasks that are not usually being performed by troops. In a second phase, the military's reactions lie on a spectrum ranging from compliance to non-compliance. These reactions are likely to be shaped not only by institutional aspects of civil-military relations, but also by the military's role conceptions about missions and their role towards politicians. Partly because of the significant influence of the principal-agent approach in civil-military relations research, it is widely accepted that once the military is ordered to do something – or is pulled in this case – it will obey, at least in states where basic tenets of civilian control have been established.Footnote 41 Yet, even democratic civil-military relations are shaped by processes of contestation and bargaining, both in countries where the military poses a threat to the democratic system and where it does not.Footnote 42 To some extent, it is even legitimate that armed forces seek to pursue their institutional interests. The fact that some of these interests may collide with those of other societal actors need not threaten democracies.Footnote 43

We suggest that the prevalent form of role conceptions is a decisive factor for how a given military adapts to different missions. Some missions might lead to contention between armed forces and governments, others might lead to the military's conditional compliance, and to some bargaining. However, whether or not the military uses the leverage gained during missions for undue political influence depends on their role conception concerning their operational profile as well as their interpretation of their adequate relationship to politics and society. We acknowledge that several pre-existing general factors may shape role conceptions, ranging from norms of professionalism, international and regional connections to other armed forces, the historical development of military organisational cultures to pre-existing critical junctures, which set certain civil-military equilibria (see Introduction to this Special Issue). Yet, all institutional aspects of civilian control being equal, once ‘pulling’ occurs, the military's reaction and adaptation to pulling will depend on its role conception. Even apparently inconsequential changes in the military's tasks thus can have notable outcomes for the behaviour of the armed forces. We build on David Pion-Berlin and Igor AcacioFootnote 44 and expand the range of expected reactions to pulling: these may include full compliance, deployment-specific compliance, conditional compliance, reluctant compliance, or active resistance.

The third phase accounts for the conditions under which pulling and the military's reactions eventually lead to changes in role conceptions. A wealth of literature on military organisations suggests that militaries react, interpret, and respond in different ways to demands by politicians.Footnote 45 Our analysis particularly focuses on missions in the area of public security and corresponding role conceptions. A clear division of labour between armed forces and police – in which soldiers deal with expeditionary missions and defence of their respective borders while police focus on internal law enforcement – is globally much less an empirical reality than often assumed in the literature.Footnote 46 Still, ‘Western’ armed forces mostly tend to have little involvement in internal public security. Hence, large-scale law enforcement missions are unlikely to sit easy with their role conceptions. We therefore expect at least a reluctant reaction to operational pulling. In countries where the armed forces used to play a significant role in internal public security and/or politics, achieving a role conception that focuses on external tasks is typically deemed beneficial for democratic civil-military relations.Footnote 47 Pulling these armed forces into long-term and large-scale public security missions contradicts this goal, as militaries could revert back to potentially problematic role conceptions.Footnote 48

Methods and data collection

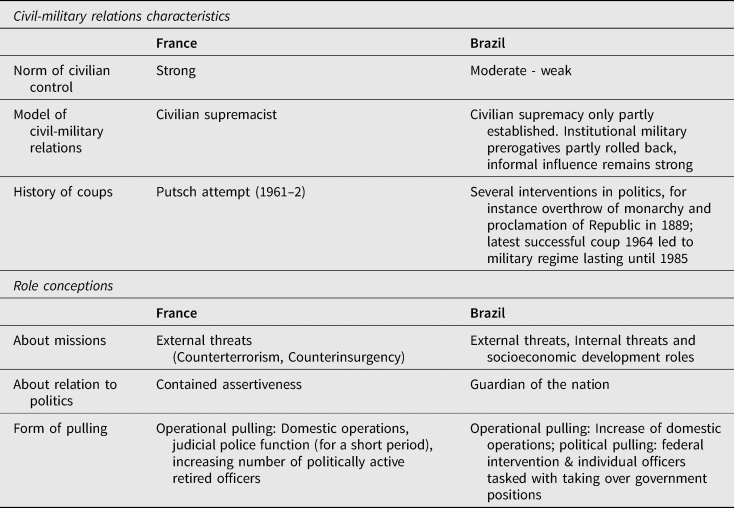

To further our understanding of the forms and conditions of pulling, we adopt an inductive approach and start from two very different empirical contexts: France and Brazil. These cases provide variation in civil-military relations and, consequently, military role conceptions. This allows us to explore how role conceptions and missions interact in the military's reaction to pulling by politicians. As we will show in more detail in the discussion of the respective cases, France and Brazil differ significantly in terms of norms of civilian control. France has traditionally had a strong civilian supremacist model, while Brazilian governments had to establish the necessary institutions for exercising civilian oversight after the end of the military regime in 1985. Due to very different experiences in nation-building and the countries’ different political trajectories, French and Brazilian military role conceptions diverge: the French military's role conception about missions has been revolving around expeditionary operations while the political role conception is marked by contained assertiveness, stemming from the forceful re-establishment of civilian control by De Gaulle after the failed 1961 putsch in Algiers. Brazil's military has historically understood itself as a crucial national institution and has felt entitled to eventually become involved in politics as ‘guardian of the nation’. Role conceptions regarding operations have historically included internal counterinsurgency and public security missions (see Table 1).

Table 1. Civil-military relations characteristics and role conceptions in France and Brazil.

For the purpose of this exercise, we combine primary and secondary sources drawing from our previous research. We now turn to our two illustrative case studies, France and Brazil.

France: Pulling and a reluctant military

In France, civil-military relations are characterised by a strong norm of civilian control over the military. Unlike other democracies, however, the French military organisation has traditionally displayed low degrees of military autonomy.Footnote 49 Already labelled la grande muette (the big silent one) in the mid-nineteenth century, the French military became even more careful at strictly adhering to its military sphere from the early 1960s. After the Second World War, the French military became progressively disbanded, which culminated in the 1961 failed putsch in Algiers. On that occasion, French President De Gaulle, in a televised message, strongly reaffirmed the norm of civilian control and, in particular, the idea that the military should stay out of politics. Chiara Ruffa argued that both organisational considerations and domestic constraints gave rise to a very distinct French military culture revolving around the idea of contained assertiveness.Footnote 50 This distinct culture together with its past memory and history give two very different role conceptions to the French military. When it comes to missions, the French military conceives of its role as almost uniquely concerned with external combat operations, such as counterinsurgency and more recently counterterrorism. When it comes to its role conceptions towards civilian decision makers, it is still considered to be very important for the military to be silent, adhere strictly to its sphere and stay explicitly out of politics. However, we witness some recent signs pointing to the potential erosion of contained assertiveness. In sum, the French military's role conception revolves around the notion of the apolitical military and the identification of external operations as the core of what the military does.

Phase 1. Operational pulling under Hollande and Macron

We detect operational pulling in France after the terrorist attacks in 2015–16. Since the 1970s, France had developed a judicial approach to counterterrorism, preferring the use of judges over the military, which traditionally played a marginal role in the fight against terrorism.Footnote 51 Notwithstanding its limited role, the French military has occasionally been used in domestic contexts. Up until 2015, the military pushed to intervene in specific contexts for limited periods to attain budgetary increases or technological updates. After 2015–16, the military was pulled into a mission that – both in terms of troop size deployed and kinds of tasks to be performed – was unheard of.

French President Hollande started pulling to increase the popularity of its remarkably weak presidency, notwithstanding a sceptical military.Footnote 52 Following the terrorist attacks at Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan, and Stade de France (2015) as well as Nice (2016), military Operation Sentinel (Sentinelle) was launched to complement Vigipirate, a security alert system introduced in 1978. More than 13,000 troops were deployed domestically – 6,000 of them in the Paris region alone – amounting to 10 per cent of the army's active-duty members. For the first time, the army and the gendarmerie were tasked with a mission-type mandate allowing for ample margins of manoeuvre when deploying in urban operations. For instance, local commanders had to meet with prefects in local districts for coordination only once a week.Footnote 53 Under Hollande, display of power in the streets and pure policing roles created a new dependency of the politicians on the military ‘by necessity’ of recuperating political capital. As Michael Goya puts it, Operation Sentinel did ‘not help much apart from reassuring the population, which is not nothing, and in particular providing oneself with a flair of energetic statesman posture, which is more unacceptable’.Footnote 54 Several experts meant to criticise Hollande precisely for using the military instrument to reassure the population and showing off as a strong leader.Footnote 55 Operational pulling did not end with Hollande's presidency. When President Macron was elected, he promoted a ‘threat-centered’ mode of governance, with high levels of alertness that never returned to the pre-Hollande time and that were not aligned to the level of threat itself.Footnote 56 While the numbers of soldiers deployed domestically went down with Macron, they were occasionally increased after specific terrorist attacks, such as the 2020 Nice attack, when he decided to revamp the instrument deploying seven thousand soldiers. Importantly, both the military and the gendarmes were provided with some of the judiciary police function, a decision considered to be highly controversial.Footnote 57 This illustration is a clear case of operational pulling because under both presidencies the military was pulled into new missions. A more recent instance, however, mirrors an attempt of political pulling.Footnote 58 In an open letter, one thousand French servicepeople – mostly retired but including 18 active-duty servicemen – warned of an impending ‘civil war’ and called for an ‘intervention by our comrades on active service’ if President Emmanuel Macron fails to halt the ‘disintegration’ of France. The letter – originally appearing in an officers’ blog – was republished in a right-wing outlet. Marine Le Pen, head of extreme right-wing party Front National, welcomed the statement, saying ‘I subscribe to your analysis and share your preoccupation,’ thereby politicising the military and causing an uproar with immediate reactions from the Minister of Defence and the Joint Chief of Staff. Both reminded the public of the political neutrality of the military. More recently, the Joint Chief of Staff announced that he would step down ‘to avoid risks of politicization’.Footnote 59 While we can still consider the kind of pulling we witness in France as operational pulling, these latest event suggests how operational pulling (and the military's reactions) offers opportunities for political pulling.

Phase 2. The military reacts to operational pulling: Reluctance and transformation

At first, the French military's reaction to operational pulling was sceptical. The kind of domestic operations required of them stood in stark contrast with its role conceptions focused on external missions. Already involved in several operations abroad, the military establishment reacted very critically to the decision of Hollande to use the military instrument more extensively. For instance, retired general Desportes declared, ‘the military component of Hollande's anti-terrorist measure is unnecessary and the war against terrorism will not be won through military means’.Footnote 60 Similarly, another retired officer commented: ‘it is inconceivable to transfer to the military authority these kinds of power’.Footnote 61 Criticisms on the military side increased particularly after the 2016 Nice attacks, when Hollande decided to ‘recall’ more than 12,000 operational reservists as yet another sign that the country was at war. Retired general Bruno Dary reflected on it, ‘the army, and more in general security forces, are very badly used’, continuing, ‘if we are at war, war is the military's business, and the military has other things to do than serve as sentinels for places of worship or train stations’.Footnote 62 Other experts suggested that the operational reserve was an empty measure, merely serving Hollande's political goals.Footnote 63 Also, at lower levels of the military echelons, soldiers said ‘they [were] very tired of this’ and denounced the limited turnover and the low morale.Footnote 64 Hence, the military was reluctant to assume this role again.

Pulling the military into Sentinel also clashed with the role conception of the French military of staying out politics: deploying the military in this function made the military much more visible and increased its autonomy, as well as its involvement in politics. While operational pulling gave them more autonomy – which they were comfortable with – it also got them more involved in politics. The French armed forces saw an increase in the number and quality of encounters with decision-makers: high-level officers of the Joint Chief of Staff met the president once every seven days instead of every forty-one days as usual.Footnote 65 But the military remained very sceptical – to a point.Footnote 66

The increased autonomy was welcomed and confirmed by the fact that the Ministry of Interior became ‘increasingly jealous of its (the military's) prerogatives’.Footnote 67 Likewise, when Hollande mobilised the reserve, he maintained the same regimental structure, which gives the military more autonomy, as opposed to smaller units, specifically tailored for Operation Sentinel.Footnote 68 But being pulled into politics made the military quite uncomfortable. ‘The presidency exchanged display of power in the streets and pure policing roles by a reluctant military for a more robust upgrade in the military's status in decision-making.’Footnote 69 With the professionalisation of the military during the post-conscription era (from 1997) and its use in expeditionary operations, deployment in the streets downgraded its position, and the politicians balanced out this frustration by upgrading the military's status in decision-making.

Phase 3. Adaptation

In a third phase, the military becomes less reluctant to operational pulling; at least one of the two role conceptions starts to erode and a growing sense of frustration about its the real ‘core mission’ takes hold. After all, Sentinel was advantageous for the French army in several respects, including an increase by 15 per cent of the French operational force – which has been linked to Sentinel and had remained frozen since 2002 – and an increase in tactical autonomy, including the right of the army to conduct inspections, and use of force in the street.Footnote 70 When Macron was elected, he immediately tried to regain control leading to the Joint Chief of Staff De Villiers's resignation. Macron maintained – to the surprise of many – the propensity to use the military quite actively, which some have labelled a ‘posture belliciste’ (‘bellicose posture’).Footnote 71 However, unlike Hollande, Macron did so in a more implicit way by continuing to employ the military in external operations, to Africa in particular, and occasionally ramping up the Sentinel instrument in the aftermath of a terrorist attack.

Paradoxically, this situation has made the traditional focus of the military on expeditionary operations less clear. Appointed in 2019, the new Army Joint Chief of Staff, Thierry Burkhard declared that ‘a high intensity conflict was not to be excluded’ but also acknowledged the importance of several other kinds of tasks and involvements, such as domestic policing.Footnote 72 While the French military is clearly maintaining a preference for external missions, it seems to have accepted the pluralism and increased complexity of its tasks. With that purpose, it has launched a number of initiatives to transform the military, such as its Vision 2030 or a very profound restructuring of its professional military education.Footnote 73 But pundits and the military alike remain critical. French historian Chéron famously denounced that ‘the French has become a soldier, a polyvalent agent, in charge of everything and no matter what’.Footnote 74

Along with the emergence of this multiple mission narrative, it seems that an erosion of the apolitical role conception has emerged as well. In several contexts, the military has been called to take a more active part in politics. For instance, the yellow jackets – a protest movement against tax increases – have asked them to intervene and politicians of diverse political orientations are increasingly asking retired militaries to become more involved and vocal and even stand for election.Footnote 75 The military remains sceptical and advocates a separation. At the same time, retired military officers have been defending their more active role in the political debate.Footnote 76 At any rate, the military has not been this vocal, popular and visible since before De Gaulle's famous televised speech.Footnote 77 To sum up, operational pulling gave the French military more visibility and was at first met with reluctance by the military itself, clashing with its role conceptions. We see small signs of change and transformations of both role conceptions whose effects remain to be seen.

Brazil: Reluctant reactions to operational pulling and a return to politics

The Brazilian military has not been engaged in a war over the country's borders since the nineteenth century. It has historically suppressed internal rebellions by peasants or slaves and fought against guerrilla groups during the recent military regime (1964–85). As a result, the operational role conception has always included a focus on security-related internal missions, as well as contributions to the country's socioeconomic development.Footnote 78 This is combined with a historical political role conception as ‘guardian of the nation’, in which loyalty to the ‘Pátria Brasileira stood above Constitution, cabinet, emperor, or president’.Footnote 79 The armed forces frequently intervened in politics when they considered it necessary for preventing harm to the country. For instance, military coups overthrew the monarchy in 1889 and led to a 21-year-long military regime in 1964. The military maintains the dubious interpretation that the coup of 1964 was a ‘Democratic Revolution’ that saved the country from a Communist takeover and refuses to cooperate in the clarification of state crimes during the regime.Footnote 80 This unrepentant stance bears implications for the military's role conceptions until today. Institutions of civilian control have been tenuously established since the end of the military regime in 1985, at times against the military's resistance.Footnote 81 The military leadership was often successful in exercising pressure on politicians and managed to maintain a considerable degree of autonomy.Footnote 82 In sum, the military's role conception has always fully embraced the need to fulfil internal operations as well as an involvement in politics whenever the armed forces themselves perceived this as necessary. After the end of military rule in 1985, this seemingly changed as the armed forces were hardly involved in public security anymore and accepted former regime opponents such as the presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Lula da Silva, and Dilma Rousseff as their commanders-in-chief.Footnote 83 However, particularly the latter two again increased the scope and size of the military's internal missions. The following presidents Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro combined this operational pulling with political pulling efforts. As the military had never rescinded its political role conception as guardian of the nation, both types of pulling contributed to the military's visible return to the political stage.

Phase 1. ‘Operational pulling’ under Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 allows the military to perform ‘Guaranteeing Law and Order’ (GLO) operations in support of state police forces but stripped the military from the right of doing so upon its own initiative. After re-democratisation in 1985, GLO operations used to take place only occasionally, within a narrowly determined frame of place and time, and usually did not involve large numbers of troops.Footnote 84 From 2010, significant ‘operational pulling’ into semi-permanent, large-scale internal public security roles took place under governments led by the presidents Lula da Silva (2003–10) and Dilma Rousseff (2011–16). This happened at a time when the operational profile of Brazil's military predominantly focused on seemingly less politically charged tasks, such as UN peacekeeping. From 2004, Brazil's military had been involved in its largest ever UN peacekeeping engagement – the Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). This mission stipulated significant adjustments by the military in terms of doctrine and training.Footnote 85 Since the armed forces received sizeable benefits in terms of new equipment and the opportunity to let troops gain practical experience, the newly found emphasis on peacekeeping was fully embraced by military leaders.Footnote 86

Yet, politicians did not seize this opportunity to fully reshape the military's operational profile towards external tasks. Instead, defence secretaries publicly stated that they wanted to use soldiers’ peacekeeping experience for countering Brazil's grave public security situation.Footnote 87 Depicting internal military deployments as ‘peacekeeping at home’, Brazilian governments deployed tens of thousands of soldiers in different missions in Rio de Janeiro, during which some neighbourhoods were occupied by troops for over a year.Footnote 88 Troops were regularly called to perform large public security missions in the following years. GLO operations thus became increasingly normalised. Despite the military's historical involvement in public security, this constituted a significant operational pulling move with political consequences.

Phase 2. The military reacts to ‘operational pulling’: Reluctance and strategic exchange

Even though internal missions, per se, do not contradict the military's role conception, the military leadership became increasingly wary of the growing scope of their involvement in public security. In an act of conditional compliance, they seized the opportunity for entering a strategic exchange with the government in order to adjust the rules of engagement in GLO operations. As defence secretaries had already publicly talked about the need to make the legal framework of GLO operations more similar to UN peacekeeping in Haiti,Footnote 89 the military leadership met a favourable environment for making demands. Legal changes were implemented in 2010 so that crimes committed by troops during GLO operations, except killings of civilians, became subject to military instead of civilian jurisdiction. However, those were not considered sufficient from the armed forces’ perspective.Footnote 90 The army commander frequently and publicly criticised the trivialisation of GLO operations as he repeated the military's view that the legal ‘protection’ of soldiers needed to be improved.Footnote 91 As governments constantly increased the operational pulling and made themselves reliant on the military for displaying their concern with public security, the armed forces’ bargaining power increased. The military's lobbying ultimately succeeded as congress and President Temer (2016–18) passed a bill that made military courts responsible for judging the killing of civilians in GLO operations.Footnote 92

In sum, internal missions, per se, did not stand in contrast to the military's operational role conception. However, their unprecedented scope and scale certainly challenged their role conception in the sense that they felt overstretched by demands for missions that did not relate to their most important, and according to a former army commander arguably neglected, role of defending the country against external threats.Footnote 93 The operational pulling triggered public statements by generals who voiced their discontent. This further normalised military officers’ involvement in political affairs at a time of increasing civil-military tensions, which had been exacerbated by the planned creation of a Truth Commission that was supposed to clarify crimes committed during the military regime.Footnote 94 In this political situation, reactions to operational pulling further contributed to a return of the military's traditional political role conception.

Phase 3. The political consequences of operational pulling

As shown in the previous section, the armed forces reacted to operational pulling by entering a strategic exchange with the government. Military leaders have used this window of opportunity for shaping conditions of internal deployments. This reinforced the military's historical role conception that takes political involvement for granted. In 2018, President Temer combined operational pulling with political pulling: he declared a ‘federal intervention’ and made army general Braga Netto responsible for the state public security sector in Rio de Janeiro. President Temer reportedly did not in advance coordinate the federal intervention with the military, which only grudgingly accepted this unprecedented political responsibility.Footnote 95

Although this would appear to show that generals were reluctant to take over political roles, the dispute with politicians over the federal intervention once more reinforced the military's historical political role conception, according to which they felt entitled to political involvement. Military leaders made demands in exchange for complying with operational and political pulling due to the federal intervention in Rio: the army commander wrote an op-ed in a magazine and called for ‘exceptional’ rules that would effectively have guaranteed impunity for soldiers who kill civilians.Footnote 96 Moreover, a former force commander of MINUSTAH – who at that time was already slated for becoming part of the next federal government – called for similar rules of engagement as in Haiti, which would have permitted the extra-legal killings of armed suspects.Footnote 97

General Braga Netto had a peculiar interpretation of the fact that the military's involvement in running the state's public security was highly popular: to him, seeing the military as the solution to Brazil's problems ‘is the despair of a country that lacks values. … When an institution with great credibility shows up, like the Armed Forces, people are beginning to think that this is the salvation of the homeland.’Footnote 98 Yet despite the professed distaste of becoming involved in politics and the apparent insight that the military can't solve Brazil's problems, General Braga Netto's comments actually reflect that many generals still see themselves as guardians of the nation who have to save the country in difficult circumstances. This is further underlined by the fact that Braga Netto became one of several active-duty army officers who later joined President Bolsonaro's government (in office since 2019).

Army commander Villas Bôas (who led the service branch from 2015–19) symbolised the military's increasingly partisan meddling in politics while claiming to remain a non-partisan state institution. Although benefiting from significant material gains during the governments of the Workers’ Party (PT) from 2003–16, the relationship between the military leadership and the PT had grown increasingly tense and the military's engrained anti-leftism motivated them to more or less openly contest political decisions.Footnote 99 Following an argument about promotions in 2015, military leaders successfully demanded that a PT member as secretary-general in the defence ministry would be replaced by a reserve army general – although this office had precisely been created in order to increase civilian influence in the ministry.Footnote 100 Despite constantly insisting on the army's alleged non-partisan nature, army commander Villas Bôas frequently commented on political affairs. Ahead of the Supreme Court's ruling in April 2018 on whether former President Lula would have to stay in prison on corruption charges, Villas Bôas and the Army High Command drafted a tweet that was widely understood as an intimidation of the judges.Footnote 101 In the presidential election campaign 2018, reserve officers supported former army captain Jair Bolsonaro who had promised to make several generals members of the government.

Bolsonaro's electoral success and the unprecedented involvement of officers in democratic politics was at least partly a result of operational and political pulling. Both types of pulling further normalised the military's presence in the provision of state services. The increase in operational pulling soon led to circumstances in which generals were made politically responsible for overseeing public security policies. The resultant political pulling further reinforced the military's self-understanding of being capable political managers, not least among the officers who had gained leadership experience in the UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti.Footnote 102 Although the military leadership maintains their official narrative to be a ‘non-partisan state institution’, the presence of several reserve officers and at times even some active-duty officers in government clearly undermines a clear-cut division between politics and armed forces.Footnote 103 The unprecedented influence on government policies also had consequences that concerned the military's operational role conceptions: the military leadership succeeded in lobbying against further public security missions unless soldiers were given legal guarantees of impunity in case of killing civilians – as a result, the previous trivialisation of GLO operations has stopped and the military is currently hardly performing the public security operations they had done so often under previous administrations.Footnote 104 However, the generals are currently more influential in politics than at any previous stage since the end of the military regime.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that accepting new roles and changes in role conceptions does not have to be problematic in the sense of threatening democracy or civilian control. If military leaderships, however, try to shape policies that affect their deployments or otherwise try to unduly exercise political influence, there might be a sign that operational pulling has created a deleterious effect for civil-military relations. In extreme cases, adaptation to operational pulling can blur the boundaries between the military's corporate interests and their political roles. For instance, if it proves popular among citizens that the military's presence in everyday life is being increased, there might be a growing incentive for politicians not only to further increase operational pulling but also to initiate political pulling. Moreover, as making their voice heard in political debates slowly ceases to be a taboo for military officers as a result of operational pulling, they might see further benefits in accepting political pulling. Understanding these dynamics allows us to answer important questions, such as: what is the relationship between the military's own role conception and their reaction to different kinds of pulling? How does the experience of pulling shape the military's role conception?

We applied our framework in an analysis of the cases of Brazil and France. Previous scholarship has identified a pulling mechanism in terms of the French response to the 2015–16 terrorist attacks. On that occasion, French President Hollande pulled a very reluctant French military into a set of roles and functions to a hitherto unforeseen extent. The French military's role conception has traditionally been wedded to the idea of external missions and related expeditionary tasks, whereas Hollande pulled the French military by deploying 13,000 soldiers in metropolitan France and, for a short time period, giving them judiciary police functions. The French army (and Gendarmerie to a lesser extent) reacted reluctantly at first and remains reluctant. As of today, however, we see some signs of growing acceptance of those new tasks, which are being incorporated into role conceptions. By contrast, the operational pulling in Brazil soon led to political pulling and contributed significantly to the military's return to political prominence. At first, the military reluctantly complied with unprecedented operational pulling, but clearly seized the opportunity to make political demands regarding rules of engagement. This reinforced the military's traditional political role conception, which remains wedded to their understanding of being the guardians of the nation. Many reserve and active-duty officers also did not refrain from taking over political offices once current President Bolsonaro won the election.

Applying our conceptual framework to two very specific cases limits the scope of the analysis presented in this article. Still, we think that this framework can travel and help make sense of pulling in other cases too. To illustrate, in Italy, the military's role conceptions revolve mainly around peacekeeping and remaining as separate from society as possible because of its collusion with the Fascist dictatorship. Yet, in recent years, politicians have pulled the military into all kinds of domestic operations – ranging from operation Safe Road against organised crime to collecting garbage in Naples. While those tasks have initially been met with scepticism and reluctance, we observe a progressive adaptation to those new roles and tasks that are giving the military exceptional visibility when compared to the past. The appointment of General Figliuolo to coordinate Italy's COVID-19 vaccination campaign is the latest sign of such transformation.Footnote 105 In Lebanon, we find further evidence of the consequences of pulling for role conceptions: politicians pulled the military into much more active operational roles in the South of Lebanon for state building purposes after the Israeli withdrawal in 2001. While the Lebanese military seemed reluctant at first to intervene in an area under traditional Hezbollah control, it did adapt in ways that seem aligned to its core role conception, which is to show it is representative of all sectarian groups present in the country, a true mirror of the nation.Footnote 106

Further research could explore alternative forms of pulling beyond those we identify but also different kinds of role conceptions that may matter in other contexts. Moreover, we still do not know the extent to which pushing and pulling are mutually constitutive and reinforce each other. Much more conceptual work could be devoted to understanding the inertial core of role conceptions, its constitutive components, its ends and means, and the conditions under which it changes. Studying pulling further bears a lot of promise. As we have seen, problems for civil-military relations often originate in governments’ initiatives. Militaries are thus drawn into the uncomfortable position of having to make judgement calls regarding the lawfulness of orders. Moreover, they need to balance principles of democratic civil-military relations: the duty of obeying lawful orders and the ideal of staying out of politics or out of missions that are not in the military's interest. Studying pulling is therefore crucial to better understand the very conditions of civilian control. Moreover, case study-based research on the consequences of pulling could provide great insights into the connection between active-duty and retired military officers. As the cases of France and Brazil have shown, retired officers sometimes apparently represent the military commanders’ views on contested issues in public discussions – thus offering the military the opportunity to shape political debates while the commanders possess plausible deniability. The necessary access for such studies remains an obstacle, but further fine-grained analysis would significantly contribute to a better understanding of the micro-level dynamics in civil-military relations.

Acknowledgements

The authors contributed equally to this article. They wish to thank Nicole Jenne, Risa Brooks, Yagil Levy, Lindsay Cohn, Anit Mukherjee, and Nina Wilén for their helpful feedback. Chiara Ruffa gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Royal Swedish Academy of History, Letters and Antiquities. Open access funding was kindly provided by Technische Universität Braunschweig.

Christoph Harig is Research Fellow at the Institute of International Relations, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Germany. Author's email: c.harig@tu-braunschweig.de

Chiara Ruffa is Associate Professor and Academy Fellow at the Swedish Defence University. Author's email: Chiara.ruffa@fhs.se