Introduction

The Iraq War has been a critical event for international security in the post-Cold War era, inflicting significant harm and economic costs.Footnote 1 The US-led invasion also challenged scholarly claims that democracies do not fight preventive wars.Footnote 2 Across the globe, citizens were predominantly opposed to the Iraq War.Footnote 3 Public opposition notwithstanding – many democratic leaders decided to join the United States in Iraq. The ‘coalition of the willing’ brought together numerous democracies for an extensive timeframe. However, while many of these countries stayed until the end of coalition operations, and some even increased their troop deployments over time, others decided to leave unilaterally before the mission's end, despite coalition requests to uphold their military commitments.

For instance, following the election victory of Spanish Prime Minister José Zapatero, the Socialist leader ordered his country's immediate withdrawal from Iraq, making good on his campaign pledge. Likewise, the Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced the departure of the country's combat forces after the Labour Party won the elections. Yet, others remained in Iraq and some even enlarged their commitment. Poland continued its military presence despite changes in the political leadership and partisan composition of government. South Korea upheld and increased its deployment, becoming the third largest troop contributor after the United States and the United Kingdom.

Throughout the course of the Iraq War, from 2003 until the end of 2008, when the mandate for the Multi-National Force in Iraq (MNF-I) expired, 18 out of 51 democratic leaders from 29 democracies announced to unilaterally withdraw their countries’ forces from Iraq. On the other hand, the remaining 33 leaders maintained deployments throughout their tenure or initiated troop withdrawals only upon the official end of coalition operations. How to explain this variation among democratic coalition members?

While recent work has advanced the study of wartime coalitions, important limitations remain. First, there is an extensive literature on the question whether democracies are more reliable than non-democracies in their alliance and coalition commitments.Footnote 4 Yet, the focus on regime type differences obscures important variation within regime types and it does not answer the question when democracies and democratic leaders become unreliable as coalition partners. Second, there is a lack of cross-case comparative work that widens the perspective beyond the United States and some of its core allies. This means that a substantial amount of political and institutional variation between democracies has been left unexplored. Third, studies on the alliance and coalition behaviour of democracies predominantly investigate formal alliances rather than informal security agreements or ad hoc coalitions for specific military operations. However, during the past three decades, multinational coalitions outside the organisational structure of formal alliances have become a major phenomenon in international politics that merits further study.Footnote 5

My findings document a complex interplay between causal factors and the existence of multiple paths towards coalition defection. Whereas prior work suggests that upcoming elections and leadership change are driving factors behind withdrawal decisions, I show that for the Iraq coalition most of the observed cases across 51 leaders from 29 democracies are not captured by such dynamics. Instead, my results demonstrate that: (1) leadership change led to early withdrawal only when combined with leftist partisanship and the absence of upcoming elections; (2) casualties and coalition commitment played a larger role than previously assumed; and (3) coalition defection often occurred under the same leaders who had made the initial decision to deploy to Iraq, and who did not face elections when they made their withdrawal announcements.

These results contrast with prior work that identified a statistically significant relationship between leadership change and coalition withdrawal and studies that highlighted imminent elections as an important driver of withdrawal decisions.Footnote 6 I argue that the observed defection behaviour can be explained when looking at leaders’ domestic situation and electoral incentives. Many of the ‘culpable’ leaders,Footnote 7 those who were responsible for their country's involvement in the Iraq War, later faced severe domestic opposition because of the deteriorating situation in Iraq. Those leaders who authorised withdrawal, did so at a time when there was still a comfortable distance to the next election. Taking the unpopular Iraq War issue off the political agenda, these leaders arguably strengthened their own domestic political position.

Throughout this article, I develop an integrative explanatory model for coalition withdrawal and apply it to the multinational coalition for the US-led ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom’ between March 2003 and December 2008. While MNF-I also saw contributions from several autocratic and other non-democratic states, the majority of coalition members were democracies. Hence this historical episode provides a rare contemporary case to investigate democratic leaders’ involvement in coalition warfare. Given the aftermath of the Iraq War and its long-term consequences for the Middle East and Western democracies’ security policies, the topic remains of imminent relevance. Drawing on original data for 51 leaders from 29 democracies, the article further provides new empirical evidence for scholarly debates on democracy and military victory, leaders and war outcomes, and the related discussion of whether terrorism ‘works’.Footnote 8

To account for complex causal paths towards coalition withdrawal, the article applies the set-theoretic method of fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). This novel methodological approach allows the integration of various explanatory factors for a systematic cross-case analysis that takes into account equifinal and conjunctural relationships between causal factors, aimed at the identification of necessary and sufficient conditions for early withdrawal.Footnote 9 This study thus provides a fresh perspective on democratic leaders and wartime coalitions, complementing extant statistical approaches and small-n case studies. This is the first study of the Iraq War to examine coalition withdrawal across all of the involved democracies at the level of individual leaders and for the entire timeframe of operations.Footnote 10

The article proceeds in five steps. To situate my argument in the literature, I begin with a review of existing studies on democracy, leaders, and coalition warfare, before developing an integrative explanatory model for coalition withdrawal. The subsequent section introduces the study's method and research design. This is followed by a presentation of the results for my set-theoretic analyses of coalition withdrawal decisions from Iraq.Footnote 11 I conclude with a summary of my findings and their implications for broader debates on democracy, leaders, and war involvement.

Democracies and coalition withdrawal

Before turning to research on democracies and wartime coalitions, it is important to define the alliance and coalition concepts. Alliances are traditionally understood as formal or informal relationships of security cooperation between states. Realists regard alliance formation as a manifestation of external balancing behaviour against aggregate material capabilities or perceived threats.Footnote 12 Coalitions, by contrast, are a form of multilateral cooperation forged for a specific military operation, to disband when that mission is complete.Footnote 13

There is a longstanding debate in International Relations as to whether democracy enhances or hinders alliance commitment and reliability. One strand of research argues that the inherent features of democracy as a regime type should strengthen states’ credibility in international interactions and their commitment to previously negotiated alliance agreements.Footnote 14 Another group of studies suggests that due to institutional elements specific to democracies, such as regular government turnover, electoral politics, and a shifting influence of public opinion and interest groups, these polities might actually be less reliable allies than non-democracies.Footnote 15 However, since this debate focuses on regime-type differences and formal alliance agreements, these studies are of limited use when trying to explain variation among democracies and democratic leaders as members of wartime coalitions.

Compared to the extensive body of research on the alliance reliability of democracies, studies on military coalitions are less numerous – although the dynamics of these prompt a number of interesting questions.Footnote 16 Existing work focuses on coalition choices of the United States, or the behaviour of its traditional allies.Footnote 17 Others assess how third parties evaluate threats from coalitions or examine the effectiveness of coalitions during interstate wars.Footnote 18 There is also comparative work on military contributions to US-led coalitions in Iraq, Libya, and against Daesh.Footnote 19

Several studies specifically explore preconditions of coalition withdrawal. Tago finds that upcoming elections tend to accelerate a departure from Iraq, while leadership turnover is unrelated to the timing of coalition defection. For Tago these results indicate that governments renege on international commitments to prevent domestic electoral consequences. In a similar vein, Cantir emphasises the centrality of domestic politics to account for withdrawal decisions and Davidson finds that when domestic political consensus on a military operation breaks down – as when the opposition and the public both favour withdrawal – departure becomes ‘just a matter of time’.Footnote 20 Pilster and colleagues show that leadership turnover enhances the likelihood of coalition withdrawal and that the risk of defection increases when democracies hold elections during coalition operations.Footnote 21 Notably, the findings of Pilster et al. contrast with studies that find democracies to keep their military alliance commitments and, more specifically, their wartime commitments despite leadership changes.Footnote 22 Most recently, Weisiger examines coalition withdrawal with a focus on battlefield circumstances, arguing that separate frontlines and prospects of defeat increase the likelihood of coalition abandonment.Footnote 23 Finally, Massie's comparison of Canadian and Dutch deployments to Afghanistan emphasises the interplay between electoral incentives, rightist partisanship, and elite consensus to account for leaders’ withdrawal decisions.Footnote 24

In sum, prior studies on coalition withdrawal enhance our understanding because they explore the conditions under which defection occurs, rather than focusing on whether democracies per se are more (or less) reliable than non-democracies. However, two important limitations remain. First, many studies generalise across large time periods. This helps to identify broader trends but also conceals substantial variation across time and within the group of democracies.Footnote 25 Hence, to gain a better understanding of the conditions that motivate decisions to defect from contemporary wartime coalitions, a focus on the post-Cold War era and specific conflicts is needed. Second, studies on specific military coalitions often investigate only a small number of countries or limit their analyses to the formation phase of an operation.Footnote 26 While these studies help to identify decision-making processes for specific cases, whether their results apply to a larger group of democracies across the entire timeframe of coalition operations thus remains an open question.

Explaining coalition withdrawal

Based on the preceding review, this section develops an integrative theoretical framework to explain early withdrawal from the Iraq War coalition. While most hypotheses relate to single conditions, none of these is presumed to be individually necessary and/or sufficient for early withdrawal from coalition operations. Instead, I expect specific combinations of conditions to be jointly sufficient to bring about the outcome and that multiple paths towards early coalition withdrawal exist. In methodological terms, this indicates that a factor is conceived as an INUS condition, that is, ‘an insufficient but necessary part of a condition, which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the result’.Footnote 27 Based on this definition, an INUS condition implies equifinality and conjunctural causation, meaning the presence of combinations of conditions and multiple pathways towards the outcome.Footnote 28

Leadership change

Changes in a country's political leadership are often associated with a change in policy. All else being equal, leadership change is thus expected to enhance the likelihood of early withdrawal from military coalition operations. There are several reasons why this might occur. First, a new leader can more easily renege on prior governments’ coalition commitments than a predecessor who authorised and justified an initial military deployment. Coming into government from the opposition ranks, it is common procedure that a new leader reviews pre-existing policies, especially costly and unpopular military operations.Footnote 29 By contrast, ‘culpable’ leaders who are responsible for their country's war involvement will have strong incentives to continue military operations because withdrawal might prompt domestic punishment by their citizens.Footnote 30 Second, a new leadership often goes hand-in-hand with a change in partisanship, which further enhances the likelihood of a policy shift.Footnote 31 Studies show that rightist governments by and large supported the Iraq War, whereas many leftist counterparts decided to abstain from military participation.Footnote 32 This means that those governments that initially decided to become involved militarily were predominantly rightist, many of which were later replaced by leftist executives. Finally, on an individual level, research finds that the policy choices of leaders are informed by their personal beliefs and formative political experiences.Footnote 33 Hence, even a change of leadership within the same political party, for instance after a resignation of the incumbent leader, can result in different policies when a political situation comes down to subjective perception and personal values.

Against this backdrop, I expect leadership change to be neither individually necessary nor sufficient but part of combinations of conditions that are sufficient for early coalition withdrawal. One such combination is a new leader with leftist partisanship. This yields the following hypothesis: H1: A change in the political leadership combined with leftist partisanship is a sufficient condition for early withdrawal from coalition operations.

Upcoming elections

Regular elections are a central requirement of democratic politics, but from a foreign policy perspective their occurrence entails the risk that electoral campaigning and party politics come into conflict with international commitments. Facing an election, a government may feel under pressure to change its foreign policy course, especially when public support for a military engagement is eroding.Footnote 34 The latter is likely to be the case when military and civilian casualties amount, adverse media coverage gains in frequency, or when a government's political opposition promises troop withdrawal upon election into office. Situations like these can provide incentives for an incumbent leader to initiate a foreign policy reversal, leading to early coalition withdrawal. Empirical studies have repeatedly shown that democratic leaders engage in less conflictive behaviour during pre-election periods. For instance, Gaubatz finds that democracies ‘resist the international pressures to start wars’ before elections.Footnote 35 Similarly, Huth and Allee demonstrate that democratic leaders behave less aggressively when elections are imminent, while being more willing to pursue territorial claims shortly after national elections.Footnote 36 Likewise, Williams finds that governments are more constrained and behave less aggressively when an election is forthcoming.Footnote 37 Haesebrouck shows that a government's position in the electoral cycle had a sizeable impact on NATO burden sharing in Libya.Footnote 38 Finally, Tago argues that many governments involved in Iraq engaged in ‘strategic position-taking’, as in terminating their country's deployment when a national election was imminent.Footnote 39 This leads to hypothesis H2: Upcoming elections are an INUS condition for early withdrawal from coalition operations.

Leftist partisanship

Politics in contemporary democracies largely comes down to party politics. While a substantial literature exists on the relationship between public policy and political partisanship, recent work shifted the focus of partisan influence analysis to the area of security studies.Footnote 40 These studies report systematic differences between parties on the left and the right on substantive questions regarding the use of force.Footnote 41 Arguments about partisanship rest on the idea that parties are ‘policy-seekers’ who aim to implement policy that reflects their ideological positions, while the ‘office-seeking’ conception sees political parties as policy-blind.Footnote 42 Leftist parties are typically more reluctant to use force, preferring non-military approaches of conflict resolution, whereas rightist parties traditionally consider the armed forces an instrument of power that can be used strategically whenever economic or military assets are endangered.Footnote 43 Comparative studies show that across Europe rightist parties have been more supportive of military deployments than their leftist counterparts.Footnote 44 As indicated, studies on the Iraq War found that rightist governments tended to support military participation, while leftist executives predominantly abstained.Footnote 45 Against this backdrop, it is expected that a left executive is part of combinations that lead towards coalition withdrawal. One such combination is the conjunction of leadership change and leftist partisanship, as formulated in H1.Footnote 46

Low coalition commitment

The dynamics between members of ad hoc coalitions reflect the familiar logic of the ‘alliance security dilemma’, where states face the opposite fears of ‘abandonment’ and ‘entrapment’, having to resolve two essential but conflicting foreign policy goals: enhancing their own security versus strengthening political autonomy vis-à-vis other states.Footnote 47 An alliance commitment might increase security by a mutual defence guarantee, but it also comprises the risk of becoming drawn into other countries’ armed conflicts and having to fight over an ally's interests, which reduces autonomy. On the other hand, non-cooperation or defection increase autonomy but they also raise the danger of being deserted in future conflicts. This logic has been applied in studies on burden sharing where it was conceptualised as ‘alliance dependence’ or ‘alliance value’.Footnote 48 Here, I use the term ‘coalition commitment’ to indicate that military operations take place in an ad hoc coalition framework. Nonetheless, members of such coalitions are often also members of the same formal alliance or have signed mutual security treaties and thus must take into account that their actions in the coalition affect the larger alliance relationship, which makes them prone to similar fears of entrapment and abandonment.Footnote 49 In addition to coalition and alliance concerns, democratic leaders must also respond to domestic audiences and make difficult choices when there is conflict between international and domestic demands.Footnote 50 Against this backdrop, I regard the size of a country's military deployment relative to its military expenditure as an observable indicator of a government's coalition commitment to the multilateral operation. I expect the greater a state's relative coalition commitment, the more likely it is this state maintains its military deployment until the official end of coalition operations. By contrast, low commitment, understood as a proportionately small military contribution, is expected to enhance the likelihood of early withdrawal from coalition operations. Importantly, this does not entail any assumptions about why states make contributions. As evidenced by many works on burden sharing, there can be a variety of reasons why leaders decide to contribute, including threat perception, prestige seeking, alliance value, financial incentives, or normative expectations.Footnote 51 This leads to hypothesis H3: Low commitment is an INUS condition for early withdrawal from coalition operations.

Fatalities

Studies show that governments’ fear of public casualty-aversion, whether grounded in fact or merely assumed, impacts upon decision-making in foreign and security policy.Footnote 52 Political leaders are sensitive to the risks associated with military engagements, which are particularly high for forward-deployed ground forces because these face a higher likelihood of injury or death than rear support units. Hence, democratic peace research has made casualty-aversion a ‘central building block’ of its argument that governments are reluctant to engage in risky military operations.Footnote 53 While military tasks and engagement intensity varied across the Iraq War coalition, all of the observed countries in this article deployed ground forces and many of them suffered military and civilian fatalities.Footnote 54 When casualties increase, so does politicians’ fear of electoral punishment by a supposedly casualty-averse public. Hence the prospect of suffering war casualties is seen as the principal political constraint on government leaders when it comes to the use of force.Footnote 55 While this conventional view has been challenged by studies that question the assumed direct relationship between casualty levels and public support and those who argue that public expectations of success are a decisive intervening factor, even these sceptical studies observe casualty sensitivity and that it poses a constraint on decision-makers’ cost-benefit calculations.Footnote 56 Indicative of this, Tago finds that combat-related deaths substantially increase the likelihood of coalition withdrawal.Footnote 57 This leads to hypothesis H4: Fatalities are an INUS condition for early withdrawal from coalition operations.

Alternative explanations

To explain early withdrawal from wartime coalitions, I draw on prominent arguments from the debate on democracy and coalition reliability and factors deemed crucial in the context of the Iraq War. My integrative theoretical framework thus offers a broad account of coalition withdrawal. Yet, critics might object to the exclusion of public opinion as a plausible alternative explanation of withdrawal decisions. Prior research has shown that public opinion can be an important factor in decisions on war involvement.Footnote 58

I do not include measures of public opinion in the set-theoretic analysis for two reasons. First, while the extent of public opposition to the Iraq War differs, across the globe ‘populations overwhelmingly opposed the war’ from the outset, as Baum and Potter note. Even among those countries that decided to partake in the Iraq War, public opposition reached 62 per cent on average.Footnote 59 Equally important, while plenty of survey data exists for the larger states involved, for many of the smaller coalition members there is simply no consistent and comparable data that covers the entire timeframe from 2003 to 2008. This makes comparisons unreliable, especially if meaningful data is required for specific points in time, for instance right before leadership changes or national elections. Nonetheless, my analysis of primary and secondary sources also yielded public opinion data for several countries, which allowed me to complement the set-theoretic analysis with case-specific information on public preferences to shed light on particular patterns, which I discuss below.

Others might criticise that I neglect individual leader characteristics that could be related to withdrawal decisions. The growing literature on leaders and war has made important contributions to our understanding of the role of individual decision-makers in international conflict.Footnote 60 However, for the present study the emphasis rests on the domestic political circumstances under which leaders make foreign policy decisions – irrespective of their individual background. Fruitful avenues for prospective studies could be to explore whether the identified paths to coalition withdrawal contain specific types of leaders and whether these patterns also apply to other conflicts.

Method and research design

This article applies the set-theoretic method of fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Because of the relative novelty of the approach, especially in the field of security studies,Footnote 61 I provide a brief summary of its basic logic and analytical procedure.Footnote 62 Since its foundation, QCA was directed at the ‘middle ground’ between qualitative and quantitative approaches.Footnote 63 As QCA analyses the specific preconditions for an outcome, causal relations are framed in the terminology of necessary and sufficient conditions: a ‘substantively important’ notion of causation, which has gained increased attention among social scientists.Footnote 64 Particular strengths of QCA are its capacity to account for conjunctural causation and equifinality.Footnote 65 The first concept concerns the idea that configurations of conditions are jointly sufficient and/or necessary for an outcome, while the second relates to the existence of multiple pathways that lead towards an outcome.Footnote 66 This makes QCA particularly amenable to test the kind of relationships derived from the literature and hypothesised in my theory section.

The fuzzy-set variant of QCA allows for qualitative and quantitative differentiation. Whereas crisp sets assume binary scores, fuzzy sets can take on any score between 0 and 1. Fuzzy sets are calibrated based on three qualitative anchors determined by the researcher. These thresholds indicate above which scores in the raw data cases are considered to be ‘fully in’ a specified set (receiving a fuzzy score of 1), when they are ‘neither in nor out’ (fuzzy score of 0.5), or when they are ‘fully out’ of a given set (fuzzy score of 0). On this basis, the direct method of calibration applies a logistic function to transform raw data into fuzzy scores.Footnote 67 The resulting fine-grained scores indicate whether cases are qualitatively rather ‘in’ or ‘out’ and to which quantitative extent they show membership in a given set.Footnote 68

Case selection: 51 leaders from 29 democracies

This article focuses on withdrawal from the Iraq War coalition as one of the rare cases in recent history where military operations occurred outside of existing alliance frameworks, lasted for an extensive period of time, and a large number of democracies were involved.Footnote 69 Given the polarised political debate about the initiation of the war and countries’ military involvement in it, the Iraq War can be considered a ‘most likely’ case for arguments on electoral incentives, leadership turnover, and partisan politics.Footnote 70 By contrast, many NATO member states witnessed broad political consensus on whether to contribute to the ISAF mission in Afghanistan, at least during the initial years of the military mission. Arguably, this made it less likely to see political campaigning on the issue.Footnote 71

The cases selected for observation are democratic leaders’ decisions to withdraw from the war coalition, including deployments to the ‘Multi-National Force Iraq’ (MNF-I) that was established after the invasion. While the first coalition forces entered Iraq on March 19, 2003, the multinational coalition was not recognised until the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1511 on 16 October 2003. The US Administration announced that 38 other countries provided military personnel to the U.S.-led ‘coalition of the willing’ in Iraq.Footnote 72 This group of countries included 29 democracies, if a combined Polity IV score of seven or higher is taken as a threshold for democratic polities. Of these I investigate 51 leaders, starting with those executives who made the initial decision to participate in Iraq and including all following leaders who assumed power before January 2008 and who made a withdrawal announcement or were in power for at least 12 months (see Table A1 for a full listing).

Outcome: Early withdrawal from coalition operations

The outcome to be explained is the early withdrawal of a country's armed forces from coalition operations in Iraq.Footnote 73 The relevant timeframe begins in March 2003 with the invasion by US-led coalition forces and it ends in December 2008, when the UN mandate for MNF-I expired and the multinational coalition disbanded.Footnote 74 The expiration of the UN mandate is treated as a natural end point to coalition operations, because it forced coalition members either to individually negotiate bilateral treaties with the Iraqi government regarding the status of their forces or to withdraw their troops altogether. Of the 29 democracies studied, only the governments of Australia, Romania, and the United Kingdom signed bilateral treaties with the Iraqi government. El Salvador and Estonia purportedly sought to find similar arrangements, but eventually decided to withdraw in January 2009.Footnote 75

Cases are coded as instances of Early Withdrawal if a government made an official announcement of full withdrawal anytime between 19 March 2003 and 31 May 2008, seven months before the end of coalition operations.Footnote 76 Some governments announced the full withdrawal of their ground and/or combat forces, while leaving in place units in supporting roles (Australia) or for helicopter observation (Denmark). For the purposes of this study, I code these as instances of early withdrawal (with a lower fuzzy score) because each government reduced its deployment in substantial, qualitative terms – beyond a mere reduction of forces. Partial withdrawal announcements or policy statements without a specified exit date were not counted as cases of early withdrawal. For instance, Italian Prime Minister Berlusconi made a tentative withdrawal announcement before regional elections, but he did not specify the time of departure. His Defense Minister Antonio Martino later made a similar announcement, but the exit date was supposed to be one year ahead and eight months after national elections, which left substantial ambiguity about this decision. Likewise, the Polish government under Prime Minister Belka declared its intent to withdraw from Iraq without a firm exit date. Hence these cases were not considered full instances of early withdrawal and received fuzzy scores of 0.30.Footnote 77

Because the article is primarily interested in democratic foreign policy decisions, its focus rests on political withdrawal announcements rather than military exit dates. This means that cases where governments’ withdrawal decisions were overturned by institutional veto players or successor governments were still coded as instances of early withdrawal, even when military operations continued eventually.Footnote 78Figure 1 shows a timeline of the Iraq War with US troop numbers, the level of non-US coalition forces in Iraq, and key dates including the Iraqi national assembly elections, the US troop surge, and the official end of MNF-I. Points in the coalition timeline refer to national withdrawal announcements, starting with Nicaragua (Bolaños Geyer) in February 2004 and ending with Albania (Berisha), El Salvador (Saca), and Estonia (Ansip) in January 2009.Footnote 79 The dashed line highlights the 31 May 2008 threshold to distinguish early withdrawal from regular departure near the end of coalition operations.

Figure 1. US and non-US troops in Iraq and sequence of withdrawal announcements (2003–10).

Explanatory conditions: Operationalisation and data

The analysis includes five explanatory conditions.Footnote 80Leadership Change refers to a change at the head of the executive after a country's military deployment to Iraq. This can be the result of elections or because the former prime minister or president stepped down and was replaced by a caretaker or successor from his or her own party.Footnote 81 My study comprises 51 leaders, including 22 leaders who came to power when their country was already involved in Iraq (fuzzy score 1.0). Nine of these were not elected but took office after the resignation of the former leader. I assign a lower fuzzy score (0.6) to these cases because the expectations associated with leadership change do not apply to the same extent as for elected leaders. For instance, Gordon Brown became British prime minister when Tony Blair stepped down before the end of his third term in June 2007 and in Poland Marek Belka succeeded Leszek Miller as prime minister after the latter's resignation in May 2004. Based on my coding rules, Brown and Belka both receive a fuzzy score of 0.6.

Upcoming Elections takes into account whether a decision for early withdrawal took place in the run-up to national elections, indicating a decision made public at the most two months before national elections were held.Footnote 82 For leaders who made no early withdrawal announcement the condition is coded positively (score of 1.0) if national elections occurred during their time in office and before 31 May 2008, as the threshold for regular withdrawal towards the end of coalition operations. For example, the Portuguese Prime Minister Santana Lopes announced his country's withdrawal from Iraq 35 days before national elections and Australia's Prime Minister Howard faced elections in October 2004 but maintained his country's Iraq deployment (both of these received scores of 1.0).

Leftist Partisanship indicates an executive's position on a left-right scale in political space. To cover my sample of 29 countries for the observed time period, my estimate of partisanship draws on data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, complemented by data from the Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project, and the Comparative Manifesto Project to fill in empirical gaps.Footnote 83 For multi-party governments, I calculate a weighted score where each party's left-right score is placed in relation to its parliamentary seat shares and the overall number of seats of the government coalition. Table A1 shows the resulting fuzzy scores (see Table A2 for raw data and the supplementary material for calibration thresholds). In the Netherlands, for instance, the conservative-liberal coalition under Prime Minister Balkenende received a weighted left-right score of 6.29 on a scale from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right), which resulted in a fuzzy score of 0.05 for leftist partisanship (almost fully out). In Italy, the multi-party Social Democratic coalition under Prime Minister Prodi received a left-right score of 3.49 that translated to a fuzzy score of 0.97 for leftist partisanship (almost fully in).

Low Commitment reflects a government's military contribution to coalition operations, relating the average troop level during a leader's tenure to a country's military expenditure during the same timeframe. Military expenditure data and deployment numbers were drawn from studies on allied participation in the Iraq War and government sources.Footnote 84 These scores are calculated as a country's share of the overall coalition effort. Hence, values below 1.0 indicate a relatively low military commitment when placed in relation to a country's defence spending. Values below 0.5 were considered ‘fully in’ the set low commitment (fuzzy score 1.0), while values above 1.5 were coded as ‘fully out’ of the set (fuzzy score 0). For example, during the tenure of Prime Minister Koizumi, Japan received a score of 0.11 indicating that the country's military deployment was disproportionately low, relative to its military expenditure (fuzzy score of 0.99), while Lithuania under Prime Minister Brazauskas received a score of 2.88 (fuzzy score 0).

Finally, Fatalities reflects the number of casualties during a leader's tenure in relation to the size of a country's overall military deployment. In addition to military deaths I take into account civilian deaths as a result of terrorist attacks against a country's nationals in Iraq. To isolate the effect of this condition, I only consider casualties that occurred before a withdrawal announcement was made. Military casualty data is from the Iraq Casualties Project,Footnote 85 whereas data on terrorist attacks draws on the Rand Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents,Footnote 86 counting incidents with at least one fatality. As for the previous condition, I place the resulting data in relation to the size of a country's military deployment. In total, there were 325 military and civilian fatalities among the observed countries, 241 of which were coded as relevant (excluding non-hostile causes such as accidents). Overall, 26 out of 51 leaders faced casualties during their time in office, before a withdrawal announcement. As a qualitative criterion, I distinguish primarily between leaders who experienced casualties and those who did not. Leaders without any casualties were assigned a fuzzy score of 0, whereas those with casualties received fuzzy scores between 0.51 and 1.0, depending on the ratio between casualties and deployed troops.Footnote 87 For example, El Salvador had three military deaths in Iraq during President Saca's time in office, resulting in a casualty-deployment ratio of 7.50 (fuzzy score 1.0), while Australia under Prime Minister Howard had two civilian deaths and a ratio of 0.19 (fuzzy score 0.75).

When do democracies abandon wartime coalitions?

The core of a QCA is the truth table procedure, which essentially tests for sufficiency.Footnote 88 However, the first step of the analysis is to test for necessary conditions. These are calculated with the consistency, coverage, and relevance of necessity (RoN) parameters of fit.Footnote 89Table 1 shows the analysis of necessity for the outcome, across all conditions and their negation. None of these pass the recommended threshold of 0.90 consistency to be considered a necessary condition for early withdrawal.Footnote 90

Table 1. Analysis of necessary conditions for early withdrawal from Iraq.

Note: L = Leadership Change, E = Upcoming Elections, P = Leftist Partisanship, C = Low Commitment, F = Fatalities, tilde indicates the negation of a condition, RoN = Relevance of Necessity.

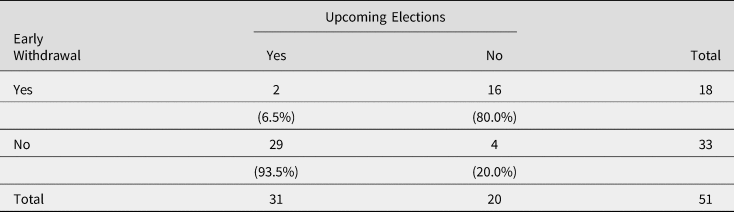

However, the relatively high value of the absence of upcoming elections (~E) indicates that early withdrawal decisions were predominantly made by leaders who did not face elections in the coming months. Table 2 presents the results of a chi-square test between upcoming elections and early withdrawal. Indeed, the test of association results show a statistically significant difference in early withdrawal decisions among leaders who faced elections and those who did not. While 31 leaders faced elections during their tenure and their country's Iraq deployment, only two of these initiated a withdrawal in a two-month period before elections (the Dominican President Hipólito Mejia and the Portuguese Prime Minister Pedro Santana Lopes). If the coding is extended to a six-month period, this adds one further case (the Bulgarian President Sakskoburggotski), without changing the general strength of the empirical relationship.Footnote 91 This is an important empirical finding, because it contradicts an expectation derived from prior studies (H2), namely that imminent elections provide an incentive for leaders to change an unpopular foreign policy to avert electoral consequences.

Table 2. Chi-square test: Upcoming elections and early withdrawal from Iraq.

Note: χ2 = 28.8, df = 1, p < 0.005.

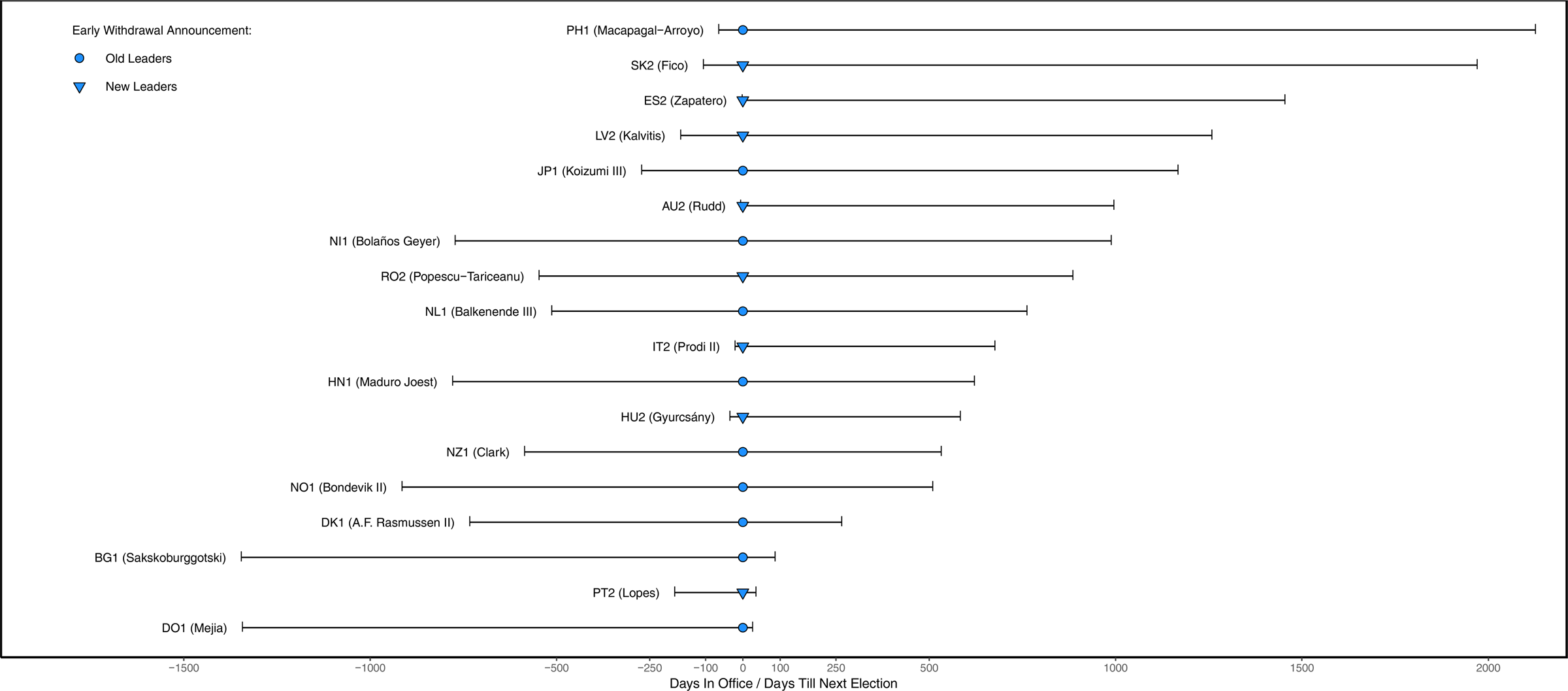

To further illustrate this pattern, Figure 2 visualises time in office and election distance for the 18 leaders who authorised early withdrawal from Iraq. Points indicate ‘old leaders’, as in heads of government were themselves responsible for their country's Iraq involvement. These could also be termed ‘culpable leaders’ to use the label introduced by Croco.Footnote 92 Triangles refer to ‘new leaders’ who inherited the war involvement from their predecessors. While I discuss individual paths to withdrawal in more detail below, two observations can be made. First, new leaders who decide to defect from the coalition mainly make this decision at the start of their time in office, often fulfilling a campaign promise. Second, when old leaders authorise withdrawal decisions, they predominantly do so in mid-term or at least with comfortable distance to the next election. Notably, this empirical pattern runs counter to expectations derived from prior studies, namely that leaders’ engage in strategic positioning by breaking international commitments in the immediate run-up to elections and that elections generally enhance the likelihood of coalition defection.Footnote 93

Figure 2. Time in office, election distance, and early withdrawal from Iraq.

Truth table analysis

The next step entails the construction of a truth table to identify sufficient conditions, as in causal factors or combinations of causal factors that consistently bring about the outcome. Table 3 shows the truth table for the outcome early withdrawal (W) and the explanatory conditions leadership change (L), upcoming elections (E), leftist partisanship (P), low commitment (C), and fatalities (F). Because the model includes five conditions, the resulting truth table contains 25 = 32 rows of logically possible combinations of conditions. The table displays all rows that contain empirical cases, omitting logical remainders (combinations without empirical cases). The ‘consistency’ column indicates the extent to which a given row is sufficient for the outcome. This measure is complemented by a parameter for the ‘proportional reduction in inconsistency’ (PRI) that indicates ambiguity in the subset relationship if its scores are substantially lower than consistency.Footnote 94 Based on these consistency measures, a cut-off point is set by the researcher to indicate the rows to be included in the Boolean minimisation procedure. Finally, the right-hand side of the truth table shows how many and which cases fit into which row or combination of conditions. Bold font designates leaders who announced early withdrawal before the end of coalition operations, all of which are situated in the top eleven rows of the truth table. Because rows ten (Dominican Republic/Mejia) and eleven (Portugal/Santana Lopes) have consistency scores and PRI scores substantially below the commonly used threshold of 0.75, I include only the top nine rows in the minimisation procedure.Footnote 95

Table 3. Truth table for the outcome early withdrawal from Iraq.

Note: L = Leadership Change, E = Upcoming Elections, P = Leftist Partisanship, C = Low Commitment, F = Fatalities, W = Early Withdrawal, bold cases hold membership > 0.50 in the outcome, logical remainder rows 26–32 are omitted for presentational purposes (see supplementary material for logical remainders).

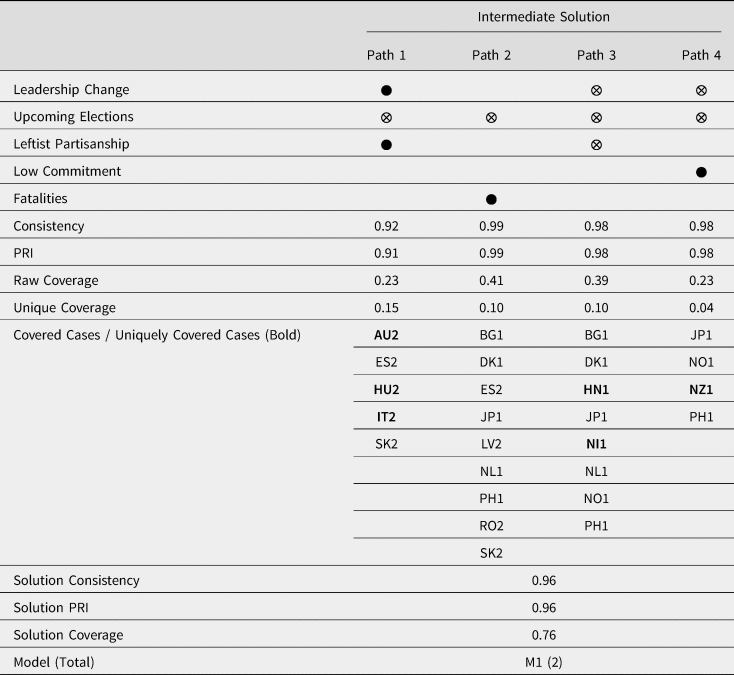

As the final step in the set-theoretic analysis, Boolean algebra is used to minimise the truth table. Based on a minimisation algorithm, the ‘QCA’ package for R calculates three solution terms that differ in their treatment of logical remainders and that can be located on a continuum that ranges from parsimony to complexity.Footnote 96Table 4 shows the intermediate solution term for the analysis of early withdrawal.Footnote 97 The table displays configurations of conditions of four alternative paths towards the outcome. I follow the notation introduced by Charles Ragin and Peer Fiss, according to which black circles (‘![]() ’) indicate the presence of a condition and crossed-out circles (‘

’) indicate the presence of a condition and crossed-out circles (‘![]() ’) their absence.Footnote 98 The centre of the table shows consistency, PRI, and coverage scores for each path. Raw coverage reflects how much of the empirical evidence a given path explains, while unique coverage refers to the share of empirical cases that are solely accounted for by the respective configuration. The table further lists which cases each path covers and which cases are uniquely covered (bold font). The bottom of the table shows the overall solution consistency, PRI, coverage, and the number of models derived.

’) their absence.Footnote 98 The centre of the table shows consistency, PRI, and coverage scores for each path. Raw coverage reflects how much of the empirical evidence a given path explains, while unique coverage refers to the share of empirical cases that are solely accounted for by the respective configuration. The table further lists which cases each path covers and which cases are uniquely covered (bold font). The bottom of the table shows the overall solution consistency, PRI, coverage, and the number of models derived.

Table 4. Paths to early withdrawal from Iraq.

Note: Black circles indicate the presence of a condition, crossed-out circles its absence.

Path 1 of the solution combines leadership change, the absence of upcoming elections, and leftist partisanship (L*~E*P). In other words, this path describes new leaders from leftist parties who did not face elections when they announced their country's departure from Iraq. This path entails prominent cases of coalition withdrawal that received substantial media coverage, Spain being the most salient example. Empirically, the conjunction is shared across truth table rows 6, 8, and 9 and it comprises one fourth of the observed instances of early withdrawal (raw coverage 0.23). In theoretical terms, this pattern lends support to the expected interaction between leadership change and leftist partisanship (H1). This means that leadership change by itself is not sufficient for early withdrawal, but only when combined with leftist partisanship.

The combination entailed in Path 1 uniquely covers Australia (Rudd), Hungary (Gyurcsány), and Italy (Prodi) and further comprises Spain (Zapatero) and Slovakia (Fico). In Australia, Prime Minister Rudd announced upon his election that he would withdraw the country's remaining combat forces, as promised during Labour's election campaign.Footnote 99 In Italy, Conservative Prime Minister Berlusconi indicated shortly before regional elections that he was considering withdrawal from Iraq but he did not specify an exit date. A year later, the new Prime Minister Prodi, heading a centre-left coalition government, announced a full withdrawal from Iraq to be completed within six months.Footnote 100 In Spain, Socialist Prime Minister Zapatero fulfilled his campaign pledge when he declared his country's immediate departure from Iraq shortly after assuming office.Footnote 101

Path 2 of the solution combines the absence of upcoming elections with the occurrence of fatalities (~E*F). Hence, this path refers to leaders who did not face elections but who experienced civilian and/or military casualties before the announcement of their country's retreat from Iraq. This conjunction is shared across truth table rows 2, 3, 5, and 6, which include nine cases, corresponding to its high raw coverage (0.41). In line with my theoretical expectations, the empirical pattern of Path 2 highlights that casualty sensitivity is an important contributing factor for withdrawal decisions (lending support to H4).

The path uniquely covers Latvia (Kalvitis) and Romania (Popescu-Tariceanu) and further includes Bulgaria (Saksburggotski), Denmark (A. F. Rasmussen), Spain (Zapatero), Japan (Koizumi), the Netherlands (Balkenende), the Philippines (Macapagal-Arroyo), and Slovakia (Fico). In Latvia, the deaths of two soldiers on patrol outside their base in Diwaniyah on 27 December 2006 made headline news and sparked calls for withdrawal from the opposition and from within the conservative coalition government of Prime Minister Kalvitis, eventually leading to the country's early withdrawal.Footnote 102 In Romania, Prime Minister Popescu-Tariceanu emphasised the grave security situation in Iraq when he submitted a formal withdrawal proposal to the National Assembly. However, this proposal was eventually rejected by the Supreme Defense Council, chaired by President Basescu, who strongly favoured the continuation of the Iraq deployment.Footnote 103

Path 3 of the solution combines the absence of leadership change, upcoming elections, and leftist partisanship (~L*~E*~P). This means that these withdrawal decisions were made by the same conservative leaders who had been responsible for the initial decision to deploy to Iraq and who did not face elections when they announced their country's early withdrawal. In other words, these are ‘culpable leaders’ whom I might have expected to remain in the conflict rather than retreat and, potentially, face domestic punishment.Footnote 104 This is a central finding because it contradicts expectations derived from prior studies. In the observed cases, early withdrawal occurred despite the absence of electoral incentives and a new political leadership (in contrast to H1 and H2). This path uniquely covers Honduras (Maduro Joest) and Nicaragua (Bolaños Geyer), and further contains Bulgaria (Saksburggotski), Denmark (A. F. Rasmussen), Japan (Koizumi), the Netherlands (Balkenende), Norway (Bondevik), and the Philippines (Macapagal-Arroyo).

While this finding seems counterintuitive at first glance, I argue that leaders’ actions become plausible when taking a closer look at their domestic situation and electoral incentives. First, case-based evidence suggests that many leaders faced intense domestic pressure throughout their involvement in Iraq, which grew as the conflict was eroding. This resonates with studies that emphasise the importance of expectations about a war's likely success.Footnote 105 For instance, Honduras seized the opportunity to end its contribution to the unpopular Iraq War and the Spanish-led ‘Plus Ultra Brigade’ when the new government in Spain announced its withdrawal decision.Footnote 106 Danish Prime Minister A. F. Rasmussen, who had been a strong supporter of US efforts in Iraq, eventually faced increased opposition to his country's involvement, from the public as well as from some of the major political parties, culminating in a withdrawal announcement.Footnote 107 Japan's Prime Minister Koizumi announced his country's departure from Iraq half a year after his re-election when polls indicated that a majority among the public opposed the deployment.Footnote 108 Likewise, Dutch Prime Minister Balkenende eventually caved in to domestic pressure and withdrew the country's troops when large parts of the population and the opposition Labour party (PvdA) spoke out against a further renewal of their country's mandate in Iraq.Footnote 109 Second, in terms of electoral incentives it should come as no surprise to see that culpable leaders decide to authorise troop withdrawal when there is still a comfortable distance to the next election (as previously discussed, see Figure 2). By removing an unpopular issue like the Iraq War from the agenda well before the next election, these leaders actually strengthen their own position vis-à-vis opposition parties.

Finally, Path 4 entails the conjunction of the absence of leadership change and upcoming elections with low commitment (~L*~E*C). This path is similar to the previous path as it also includes leaders who made the initial decisions to engage in Iraq, but it is restricted to low commitment countries and makes no assumptions about partisanship. The combination of Path 4 uniquely covers New Zealand (Clark), and further includes Japan (Koizumi), Norway (Bondevik), and the Philippines (Macapagal-Arroyo). In New Zealand, the Labour government under Prime Minister Helen Clark seized the opportunity to withdraw its contingent of sixty army engineers after they completed two six-month rotations in 2004.Footnote 110 The initial decision to deploy a small contingent of non-combat forces reflected the Clark government's critical stance towards the US-led invasion, while at the same time wanting to contribute to the reconstruction effort in Iraq.Footnote 111

To visualise the allocation of cases and the empirical fit of the set-theoretic results, I construct five scatter plots. Figure 3 shows fuzzy-set case membership in the solution term (top left) and its four constituent paths vis-à-vis the outcome early withdrawal.Footnote 112 The diagonal line differentiates cases that have a higher value in the outcome than in the solution (above the line) from cases with a higher membership in the solution than in the outcome (below the line). While the former indicates sufficient conditions, the latter signals necessary conditions. In set-theoretic terms, it is important to differentiate cases that rather hold membership in a given set (Xi > 0.50) from those that are situated rather outside that set (Xi < 0.50). This effectively divides the plots into six distinct areas that differ in theoretical relevance.Footnote 113

Figure 3. Early withdrawal from Iraq: Overall solution and alternative paths.

Figure 3 shows that the solution term is almost fully sufficient for early withdrawal because nearly all cases are placed on or above the main diagonal (solution consistency of 0.96). In essence, the plots show three groups of cases. Cases in the lower left corner have low fuzzy-set scores in the outcome and the solution and therefore can be regarded largely irrelevant for the theoretical argument. By contrast, 16 of the observed 18 cases of early withdrawal hold membership above 0.50 in at least one solution path (blue points in the top left plot), many of which can be considered typical cases (inside the shaded area). For the four constituent paths of the intermediate solution, labels indicate cases that are uniquely covered or best described by each respective path (blue points). The two cases in the top left corner of the first plot show the outcome but are not covered by the solution. However, except for the Dominican Republic (Mejia) and Portugal (Santana Lopes), all instances of early withdrawal are accounted for by at least one path of the solution term. Importantly, across 51 leaders, there are no deviant cases that hold membership in the solution but do not show the expected outcome (lower right corner).

Conclusion

Democratic war involvement is increasingly happening in multilateral frameworks comprised of ad hoc coalitions of states. The multinational coalition in Iraq brought together numerous democracies – many of which decided to leave before the mission's end, despite allied requests to uphold their contingents. Others remained in the country and some even increased their commitment. Prior work has dealt extensively with the inherent features of democracy and the question of whether these enhance or hinder commitment and reliability in foreign and security affairs. Yet, few studies have investigated the conditions under which democracies become unreliable as coalition partners, and even less have conducted such analyses from comparative perspectives at the disaggregated level of individual leaders. To address these gaps and explain the observed variation, this article took a set-theoretic approach that combines factors rooted in domestic politics – partisanship, leadership change, and upcoming elections – with the consideration of civilian and military casualties and countries’ relative contributions to the coalition effort.

My results shed light on the complex interplay of conditions that influence democratic leaders’ conflict behaviour. In sum, three main findings can be derived from the analysis. First, the empirical analysis shows that when combined with leftist partisanship and the absence of upcoming elections, leadership change led to several prominent cases of early withdrawal. I identified this pattern in Australia, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, and Spain (Path 1 in Table 4). In these countries, opposition leaders campaigned on ‘bringing the troops home’ – in line with public opposition to the war – and they fulfilled this promise after their electoral victories. That being said, my results underline that leadership change alone was not sufficient for coalition defection. In fact, 64 per cent of new leaders continued their country's Iraq deployment (see Table A1). This finding contrasts with studies that identified a statistically significant correlation between leadership change and coalition withdrawal.Footnote 114 In sum, my results resonate with prior work suggesting that democracies rather keep their wartime commitments despite leadership changes.Footnote 115

Second, my analysis indicates that casualties and coalition commitment, while not individually decisive, were important contributing factors for early withdrawal decisions. In particular, Path 2 of the solution (see Table 4) documents that many leaders decided to depart from coalition operations in Iraq after suffering civilian or military casualties. This finding carries policy implications because it suggests that casualty sensitivity played a larger role than previously assumed. This also contributes to the related debate on whether terrorism ‘works’ in the sense that terrorist groups achieve their political aims.Footnote 116 Indeed, several governments announced withdrawal shortly after suffering deaths from terrorist attacks. The most prominent case is Spain, although one must note that the attack on commuter trains in Madrid occurred three days before elections and the opposition leader Zapatero had made the Iraq withdrawal a campaign goal before that time. But similar dynamics occurred elsewhere. The Philippines declared their departure after a contractor had been kidnapped by insurgents and threatened with beheading unless the country would withdraw.Footnote 117 Bulgaria experienced substantial military casualties and terrorist attacks, before eventually withdrawing in the face of rising public opposition.Footnote 118 In Latvia, the deaths of two soldiers sparked protests and public criticism of the mission, which eventually led to early departure from Iraq.Footnote 119

Finally, the observed cases show that electoral incentives did not yield the expected effect because all pathways towards withdrawal include the absence of upcoming elections. This strikingly diverges from prior studies’ argument that leaders renege on wartime commitments to avoid electoral consequences and the finding that the risk of defection increases when democracies hold elections during coalition operations.Footnote 120 My analysis shows that many early withdrawal decisions were made by the same leaders who had been responsible for the initial decision to deploy to Iraq and who did not face elections when they announced their decision. I argue that leaders’ actions can plausibly be explained when looking at their domestic situation and electoral incentives. Many of the leaders who were themselves responsible for their country's Iraq involvement faced intense domestic pressure because of the deteriorating situation in Iraq. Those who eventually decided to withdraw, did so when there was still a comfortable distance to the next election (as visualised in Figure 2). By taking an unpopular issue like the Iraq War off the political agenda, these leaders arguably strengthened their own domestic position.

Wartime coalitions frequently encounter the problem of how to sustain the military effort over longer time periods. At the same time, democratic leaders face domestic opposition and the public demands that its preferences are reflected in foreign policy decision-making. Further research may show, for instance, whether dynamics similar to those identified in Iraq were at play during NATO's ISAF mission in Afghanistan.Footnote 121 Prospective studies could also explore whether the identified pathways contain types of leaders with specific character traits and whether such patterns can also be found for other conflicts.Footnote 122

Author ORCIDs

Patrick A. Mello, 0000-0002-0751-5109

Acknowledgements

For constructive comments on earlier versions of this article I am grateful to Klaus Brummer, Jason Davidson, Nina Guérin, Tim Haesebrouck, Christian Hagemann, Jeroen Joly, Kai Oppermann, Solveig Richter, Ingo Rohlfing, Stephen Saideman, James Strong, Brian Urlacher, and the editors and reviewers of EJIS. I would also like to thank audiences at the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt (2013), the International Studies Association in New Orleans and Atlanta (2015 and 2016), the Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt (2016), the IR Section Meeting in Bremen (2017), the Technische Universität München (2017), the Universität Erfurt (2017), and the European Workshops in International Studies in Groningen (2018).

Supplementary material

To view the online supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/eis.2019.10

Patrick A. Mello is Visiting Scholar at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on international security, foreign policy analysis, and qualitative research methods, especially fuzzy-set QCA, on which he is currently completing the book Qualitative Comparative Analysis: Research Design and Application for Georgetown University Press. He is also the author of Democratic Participation in Armed Conflict (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) and his articles have appeared in leading journals such as the European Journal of International Relations; British Journal of Politics and International Relations; Contemporary Security Policy; and West European Politics.

Appendix

Table A1. Democratic leaders, fuzzy-set conditions, and outcome early withdrawal.

Table A2. Raw data.