Introduction

Postconflict peacebuilding has been part of the core business of multilateral organisations and agencies since the publication of the Agenda for Peace in 1992, and the first systematic attempts at peacebuilding in the Balkans, Timor Leste, and elsewhere. More than twenty major peacebuilding operations have been undertaken, peacebuilding was institutionalised via the creation of the United Nations Peacebuilding Commission and its architecture in 2006, and its Peacebuilding Fund has spent more than US $1 billion on programmes in more than forty countries, supplemented by extensive bilateral spending.Footnote 1 Parallel to this, scholarship has emerged examining peacebuilding from a conceptual perspective, as well as via individual cases, with its focus evolving from the liberal peacebuilding paradigm and its critics, to local and hybrid forms of peacebuilding, as well as post-liberal and illiberal forms.Footnote 2

Peacebuilding policies and practices potentially represent a strong exercise of power by external actors. As Roland Paris put it, ‘to the extent that peacebuilding agencies transmit [such] ideas from the core to the periphery of the international system, these agencies are, in effect, involved in an effort to remake parts of the periphery in the image of the core.’Footnote 3 Yet peacebuilding policies and programmes frequently fail to achieve their goals, including creating peaceful and stable societies, promoting democratic institutions, reforming economies, restructuring the security sector, or promoting rule of law and respect for human rights.Footnote 4 Scepticism about the successes of postconflict peacebuilding, understood as ‘action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid relapse into conflict’, runs through the literature.Footnote 5 From the perspective of reducing the recurrence of violent conflict, postconflict peacebuilding efforts may often be successful, but the resulting negative peace falls far short of the stated goals of peacebuilding programmes, which aim at institutional re-engineering and political, social, and economic transformation towards positive peace.Footnote 6

Externally-oriented explanations for the success or failure of peacebuilding efforts range from a micro-level diagnosis of specific peacebuilding practices (institutional over-reach, lack of appropriate expertise and experience, and non-transferability between contexts), to macro-level explanations that focus on the compressed process of state-building and the conflicts created by ‘shock treatments’ applied to fragile states and institutions.Footnote 7 More fine-grained accounts and case studies have, however, focused on the local actors, and the ‘interaction dynamics between external and domestic stakeholders’ or on the ‘friction’ in ‘vertical and asymmetrical relations between the global and the local’.Footnote 8 They highlight the intertwined nature of international-local interactions, which often (as our empirical analysis below notes) go beyond relations between local and international elite actors.Footnote 9 The different outcomes of the various peacebuilding interventions thus result from the complex interplay of power/resistance of external and local actors, the implicit assumptions and theories of change held by external actors, and the hybrid assemblages that may result.Footnote 10

This article builds on these insights to unpack the different forms that this co-constituted relationship of power and resistance can take by drawing upon the International Relations literature on power to theorise more systematically the power/resistance relationship, and demonstrates its utility with a detailed focus on a single case study – international efforts at peacebuilding in Burundi – that spans more than twenty years. We first review current conceptualisations of the power relationship and forms of resistance between external and local actors in peacebuilding; following this, and drawing upon the literature on power and resistance in International Relations, peacebuilding research, and social theory, we deploy a three-part conceptualisation to illustrate how different forms of power/resistance can be deployed and interact in peacebuilding practices.Footnote 11 We agree that ‘there can be no adequate understanding of power and power relations without the concept of “resistance”’, and thus supplement a unidirectional vision of power as exercised by external actors and resisted by local agents, to treat resistance as an active process (and exercise of power) by which local actors bend and fuse peacebuilding practices to their ends.Footnote 12

The subsequent, and most detailed, part applies these insights to six dimensions of postconflict peacebuilding in Burundi: attempts to address the sources of insecurity and violence through power sharing, land reform, human rights promotion, security sector reform, promoting gender equality, and transitional justice. Burundi represents an excellent case for analysis for several reasons. First, the international engagement in Burundi, especially after the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, was deep, detailed, and resource intensive, and was seen as a flagship case for the UN Peacebuilding Commission. Second, the twenty-year time frame of external intervention (from the signing of the Arusha Accords in 2000) is sufficiently long that one can trace the development of different forms of resistance to international policies and programmes, in all of the issue areas noted above. The effectiveness of a wide range of local actors’ power/resistance to external intervenors’ exercises of power often manifests over the medium to long term, which is critical for a balanced assessment of the power/resistance relationship in peacebuilding. As Daniel Drezner points out, most accounts of power have implicit temporal biases, with longer-term analyses adopting more expansive definitions of power.Footnote 13 The ways in which the Burundian case may be considered as an exemplar will be addressed in the conclusion, and we will examine some of the challenges to generalising from this case for further research into power, resistance, and postconflict peacebuilding. The overall aim is thus to contribute to the peacebuilding literature and to provide empirical insight into how power and resistance interact in world politics.

Power/resistance and peacebuilding

Most analyses of the external peacebuilding efforts operate with an under-theorised concept of power and the mechanisms by which specific outcomes – such as market liberalisation, rule of law, or democracy – are to be realised. How external actors attempt to exercise power in peacebuilding has also remained somewhat under-conceptualised, and theoretical treatments of power in International Relations remain disconnected from empirical analyses of peacebuilding. As Graeme Young notes, ‘while the role of power in both peacebuilding and neoliberalism is commonly highlighted, the way in which this power is conceptualized is not entirely consistent.’Footnote 14

Two specific attempts to theorise power in peacebuilding are Michael Barnett and Christoph Zürcher's ‘peacebuilder's contract’ and Roger Mac Ginty's four-part model of interaction between external intervenors and local agents. Barnett and Zürcher's analysis conceives of peacebuilding as a bargaining situation between peacebuilders, state elites, and subnational elites, who are in a ‘situation of strategic interaction, where their ability to achieve their goals is dependent on the strategies of others’,Footnote 15 and their conclusion is that the most likely outcome is compromised peacebuilding, in which local elites and external actors jointly shape how peacebuilding programmes unfold.Footnote 16 Mac Ginty, by contrast, explicitly invokes the concept of resistance and focuses not only on the compliance and incentive power of liberal peace promotors, but also on how local actors present their own alternatives, and the ‘ability of local actors, networks and structures to resist, ignore, subvert, and adapt liberal peace interventions’.Footnote 17 These kinds of theorising are an advance over versions of liberal peacebuilding that overestimate the power of external actors to impose their vision of the state, economy, and society, but they still have three shortcomings. First, Barnett and Zurcher's conception of power is restricted to an interactional or bargaining concept that does not capture the way in which institutional, structural, or other forms of power may be exercised. In addition, they do not explore in detail the different forms of power/resistance that local actors might deploy to resist the aims of external interveners. Finally, such visions tend to take actors’ (both local and external) identities and interests as fixed, rather than co-constituted, treating the ‘local’ ‘as something “out there” to be discovered, understood or empowered’.Footnote 18 It thus ignores how local actors are also embedded within the financial, organisational, programmatic, and rhetorical networks of the international peacebuilding community in ways that shift power and reconstruct relationships within ‘the local’ to advance the power-accumulating, state-building, or rent-seeking agendas of some groups in ways that are often hidden from interaction or bargaining analyses.Footnote 19

We first to draw upon the accounts of power of scholars such as Stefano Guzzini or Michael Barnett and Raymond Duvall to enrich the debate among peacebuilding scholars about power/resistance. Terms such as ‘bargaining’, ‘structural’, ‘institutional’, or ‘productive’ power (among others) have been deployed to dissect the forms and practices of power.Footnote 20 For our purposes, we will group these accounts into three dimensions of power – bargaining, institutional, and productive – to capture the different forms of power/resistance that can develop between local and external actors in peacebuilding.Footnote 21 Hence one has:

• bargaining power between rational, self-interested, gains-maximising actors, where there is an observable conflict of interests and external actors manipulate the costs and benefits to ensure compliance with particular programmatic and policy choices;

• institutional power where external actors attempt to structure the field in which specific policies and programmes are imagined, designed, and executed through institutional engineering that sets agendas and shapes the range of choices available to exclude certain policy or political options;

• productive power is exercised in attempts to (re)constitute political, economic, and social subjects and subjectivities (identities) along norms and principles of external actors so as to align the identities and preferences of local actors with the external peacebuilding project and to marginalise ‘those who cannot be described as subscribing to liberal and neoliberal rationalities’.Footnote 22

All these different forms of power could be deployed in externally led peacebuilding programmes and policies, and the package on offer in postconflict peacebuilding goes well beyond a bargaining relationship over particular policies and programmes. For example, parallel to efforts to negotiate the terms of specific postconflict peacebuilding programmes and policies, external actors often attempt to shape national policies around preferred institutional outcomes, such as power-sharing constitutional systems, or particular configurations of civil-military relations, all of which represent institutional power. And by promoting a vision of appropriate forms of social and political life through the positive association and normalisation of such ideas as competitive party politics (which depend on the constitution of voters as having non-ascriptive and issue-based bundles of interests, rather than identity-based and singular voting preferences), individuals as bearers of political and social rights, or gender equality – they contribute to the creation of political subjects and subjectivities (identities) via an exercise of productive power.Footnote 23 All of these, for example, can be found at work in postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the Dayton Peace Accords offered incentives to conflicting parties to engage in peace talks, engineered a consociational political system that was intended (but failed) to create cross-ethnic political processes, and attempted to reconstitute the space of civil society and political participation to accord with Western ideas of democratic political competition.Footnote 24

As the Bosnia case highlights, none of these exercises of power are foreordained to succeed or to be mobilised in any given context – this is an empirical question. Local actors mobilise their own forms of power to mount resistance in ways that interact with, and may directly or indirectly challenge, external actors’ attempted exercises of power. Hence at a minimum one needs to theorise the different forms this power/resistance can take, and how it can interact with that of external actors.

The literature on resistance in social theory mainly focuses on overt forms of resistance as large-scale manifestations of social power that ‘denotes a type of “organised”, “collective”, “principled” and “systematic” action’; or ‘everyday forms of resistance’ that ‘takes the form of passive non-compliance, subtle sabotage, evasion and deception’.Footnote 25 Overt resistance fits within a bargaining conception of power, which, while important in some contexts, is unlikely to be the only form of resistance to peacebuilding programmes and policies. On the other side, everyday – and mainly covert – forms of resistance are not necessarily undertaken from a subordinate position, since ‘local actors’ greater understanding of local contexts, high legitimacy, extensive human networks, normative or religious ties, and so on’ mean that they ‘frequently wield stronger power than external actors’.Footnote 26 This is an advantage for research, since resistance by local actors achieves tangible outcomes in political, social, or economic domains that do not require deep ethnographic understandings to uncover. Exploring the relationship between different forms of power/resistance to external exercises of power requires some elaboration, however, to capture the different co-constituted relationships of power/resistance, and to acknowledge contexts in which (as in our case study), the local actors include powerful state elites as well as civil society and opposition actors.Footnote 27

Within the peacebuilding literature, the different forms of resistance that local actors may deploy have been analysed primarily by scholars focusing on the ‘local turn’, on hybrid peacebuilding, or on the non-linear processes unleashed by the interaction of local and international actors.Footnote 28 As noted by Oliver Richmond and Audra Mitchell, ‘local actors may openly reject international policies or strategies, they may implicitly reject them by failing to comply, foot-dragging, or they may find ways of co-opting them into localized political project by renegotiating them with their sponsors, using their cooperation and compliance as a bargaining tool.’Footnote 29 Or, as noted by Ursula Schroeder et al., they may adopt strategies of ‘adoption, adaptation or rejection’, through forms of resistance that can include selective adoption or mimicry of norms, organisational structures or practices (in the security sector), to make them congruent with local beliefs and power constellations, all of which reflects resistance that contests not only bargaining power, but the productive power of the global norms and practices promoted by external peacebuilders.Footnote 30 This is an ongoing process, not a one-shot bargaining interaction, and since ‘the global and the local are in constant confrontation and transformation’ the relationship must be analysed over a longer time frame to capture the frictional or ‘abrasive encounters where ideas, practices, norms, and actors, meet and result in new or unintended outcomes through adaption, disengagement, hesitation, rejection and co-option.’Footnote 31 The upshot as noted by David Chandler, is often ‘hybrid outcomes [that] … indicate that the “top–down” shaping of state institutions has little broader social impact and that liberal aspirations are easily undermined or blocked by “resisting” or countervailing societal practices and institutions.’Footnote 32

These discussions of the outcomes of resistance as a form of power do not, however, always link to broader theorisations of forms of power/resistance. Hence the co-constituted nature of power/resistance, and the way in which different dimensions of power/resistance can interact, are often less well explored, and the ‘three core elements of resistance regarding the subjects, object and means of resistance have remained ambiguous’.Footnote 33 As Stefanie Kappler and Nicolas Lemay-Hébert note, even critical approaches to peacebuilding have difficulty overcoming the top-down nature of analyses: a focus on hybrid forms does not ‘problematize the underlying power relations … and often implicitly assumed that such power relations are evened out in the process of hybridization’, while a focus on the ‘everyday’ implicitly assumes ‘that power in the everyday is so dispersed that it can be found everywhere and has therefore almost become meaningless as an analytical category’.Footnote 34 Similarly, as Suthaharan Nadarajah and David Rampton point out, ‘the liberal peace itself long sought to engage with the local and other decentred or non-state forms as a deliberate transitional strategy of peace- nation- and state-building.’Footnote 35 The result can be that ‘an account of resistance continues to be vague’, or that it continues to take actors’ identities and interests as given or fixed, when changing these is precisely the object of the exercise of productive power (in reshaping, for example, gender relations).Footnote 36

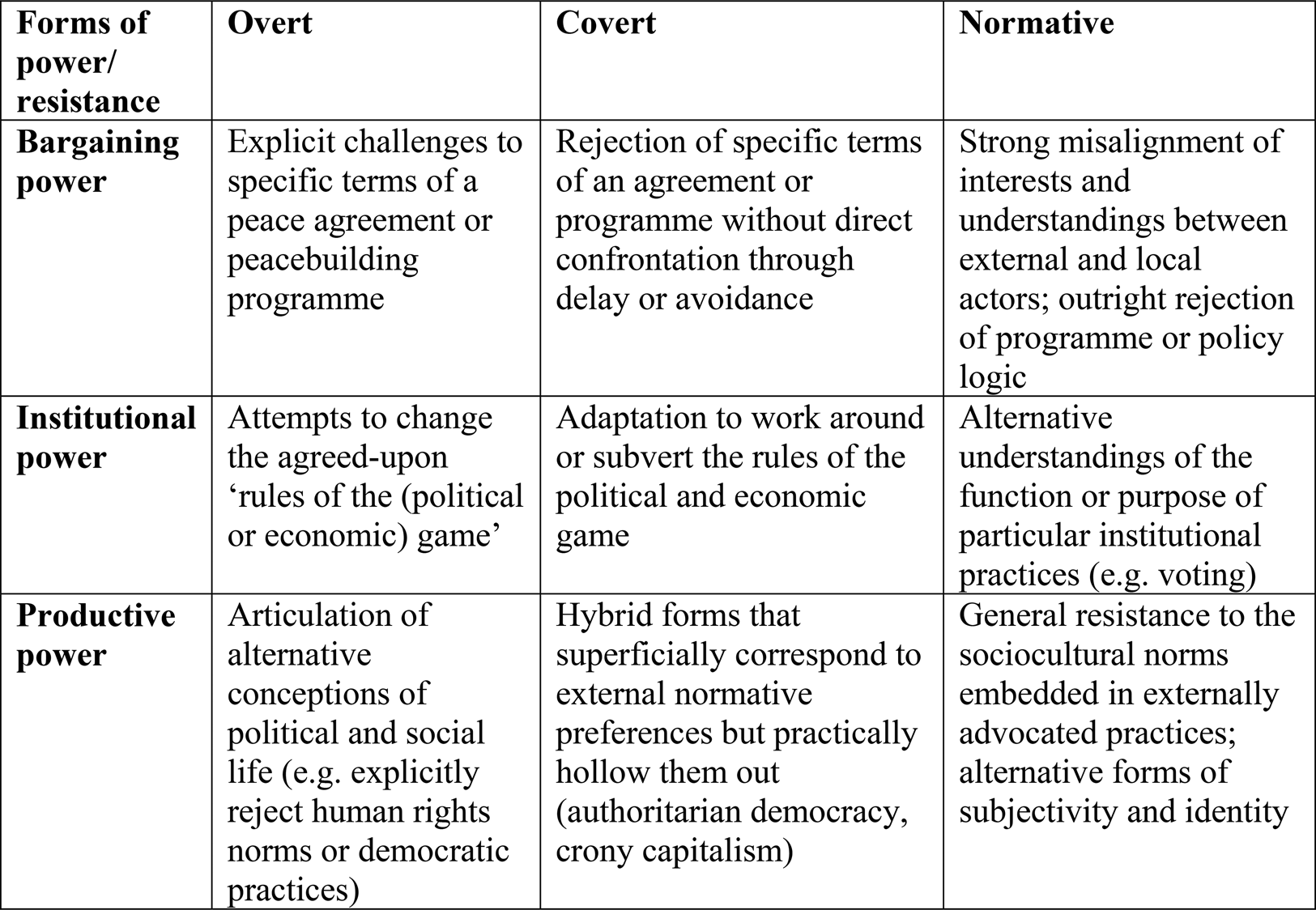

We proceed to build upon these observations a conceptualisation of the power/resistance relationship in three steps. First we argue that the super- and subordinate relationships that exist between external and local elite actors can include both overt and covert ‘everyday’ forms of resistance that leave visible traces but are based on a hidden transcript of local power, in particular via sovereign entitlements, which ‘can create a protected space where the international community cannot go: inside party meetings, prison cells, militia meeting places, wedding banquets and private audiences – in other words where the real decisions are made. This protected space endows local rulers with the power to resist, subvert, and re-appropriate.’Footnote 37 While not exactly in a subordinate position shorn of material endowments, local elites operate within these inaccessible spaces to resist in particular institutional expressions of power by external actors. Second, we adapt Marta de Heredia's definition to focus on the relationship between external and local actors, defining peacebuilding resistance as ‘acts undertaken by individuals or collectives to mitigate or deny external actors’ attempts to reshape political, social and economic relations and to advance their own agenda’, and to incorporate the ways in which resistance may draw upon alternative understandings and subjectivities.Footnote 38 Third, we draw upon three of Jocelyn Hollander and Rachel Einwohner's forms of resistance (overt, covert, and unwitting – which we have relabelled ‘normative’) to mirror the three forms of power, with the resulting matrix presented in Figure 1.Footnote 39

Figure 1. Forms of power/resistance.

Our expectation is that overt resistance to exercises of power would initially be incorporated into the outcome of peace agreements and specific peacebuilding programmes that involve direct engagement with local actors, such as the terms of disarmament, demobilisation or reintegration programmes (bargaining power), the nature of electoral systems (parties, quotas: institutional power), or specific practices constitutive of liberal subjects (individuals as bearers of equal rights: productive power). Covert resistance would be manifest when the terms of an agreement or programme are not implemented (or are slow to be met by local actors) via foot-dragging over specific reforms, or when formal institutional arrangements and their embedded liberal norms (productive power) are superseded by parallel forms of governance (neo-patrimonial or ethnically-driven forms of governance, rent-seeking and distribution). Finally ‘normative’ resistance is manifest when there is an incomprehension, disconnect, or misfit between for example, institutional practices such as competitive party voting in elections versus ascriptive allegiances within groups, or sociocultural norms surrounding such things as gender equality and formal versus informal justice. This can be conscious or unconscious, and captures how local ‘actors experience and make sense of [the] transformations’ that are being proposed or imposed, and the exercises of power that accompany them.Footnote 40 In the next sections, we will focus on these different forms of resistance and the interplay of power/resistance to demonstrate how diverse local actors over time deploy power resources to resist efforts to reshape economic, political, and social structures and practices, in order to maintain or reinforce their power, and how this co-constitutes the power/resistance relationship.

Power/resistance in postconflict Burundi

‘Peace’ was to come to Burundi as a result of the 2000 Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, which ended a protracted civil conflict, punctuated by episodes of large-scale violence and mass killings since 1965. The Arusha Accords contained extensive provisions for power sharing, equitable representation in state institutions, security sector reform (military, police, judiciary) and a framework for reconstruction and development. Designed as a means to gain agreement among conflicting armed groups and prevent future conflict, it deferred many specific issues (such as the size of the army or police force, or truth and reconciliation processes) to a transitional government, or subsequent decisions. Mostly top-down in its approach, the Arusha Accords only marginally supported peacebuilding efforts initiated at the local community level, a shortcoming that has been identified as one of its main weaknesses.Footnote 41 Continued instability and the failure of all armed groups to join the peace process until 2008 also opened the way for extensive international involvement, beginning with the UN Operation in Burundi (ONUB), followed by direct engagement of the newly-created UN Peacebuilding Commission in 2006 and the United Nations Integrated Office in Burundi (BINUB). Burundi received more than US $75 million from the Peacebuilding Fund since 2007, in addition to approximately US $800 million in bilateral ODA since 2004.Footnote 42

The UN Peacebuilding Commission's 2007 ‘Strategic Framework for Peacebuilding in Burundi’ identified eight priority areas for intervention: promotion of good governance; implementation of a comprehensive ceasefire between the government and opposition groups;Footnote 43 security sector reform; justice, promotion of human rights and action to combat impunity; land reform and socioeconomic recovery; mobilisation and coordination of international assistance; the subregional dimension; and the gender dimension.Footnote 44 These expanded upon the four pillars of the Peacebuilding Commission – promoting good governance, strengthening the rule of law, reform of the security sector, and ensuring community recovery.Footnote 45 In implementing the Strategic Framework, the international community displayed all three above-mentioned dimensions of power: bargaining power was notably exercised through a Cadre de Dialogue et de Concertation (Framework for Dialogue and Concertation) established in 2008, and through which these priorities and their implementation were discussed with the government, the local civil society, and the international community;Footnote 46 institutional power was exercised, for instance through the design and implementation of transitional justice mechanisms (explored below); and finally, productive power was visible in how civil society activities were controlled and oriented, and in how some priorities, relating for example to gender equality, were foregrounded.Footnote 47 The eight priorities established by the Strategic Framework were also largely in line with the content of the Arusha Accords, as detailed in its five protocols.Footnote 48 As will become apparent in our empirical analysis, the good will initially expressed by a large part of the Burundian elites towards the Arusha Agreement and the Peacebuilding Framework did not last.Footnote 49 The progressive exercise of covert (and later overt) resistance by local elites and power holders undermined virtually all of the efforts of the international community (as well as regional actors) at peacebuilding.Footnote 50

The next sections elaborate on this via a brief analysis of six areas in which different forms of resistance to external peacebuilders’ exercises of power can be discerned and have been exerted by a multiplicity of ‘local’ actors, from the ruling party, to civil society organisations, to traditional local authorities, and even to specific individuals. The first three sections (political representation, power sharing, and ethnic quotas; land reform; human rights promotion) illustrate cases of power/resistance primarily initiated by the government and/or the CNDD-FDD elites, while the last three (security sector reform; gender mainstreaming and gender equality; transitional justice) exemplify more complicated situations, where various actors, from civil society organisations, to traditional authorities, and to individuals, resist externally imposed norms and/or institutions. This division highlights the fact that multiple local actors, and not just the Burundian government, have been resisting external peacebuilders, and that multiple disagreements cut across various sections of the Burundian population and elites.

The six areas were also selected because they all involve more than exercises of bargaining power; they represent attempts to shape the choices available to local actors and set agendas in such a way as to exclude certain policy or political options (political representation, land reform, security sector reform) and/or constituting political, economic, and social subjects and subjectivities (identities) to correspond to predominantly Western liberal understandings, norms, and subjectivities (gender mainstreaming, human rights, transitional justice). Although we cannot fully populate the matrix in Figure 1, these six issue areas represent excellent cases through which to uncover different forms and practices of resistance. Empirically, the study of resistance faces similar challenges to those identified by Lukes with respect to power: it ‘is at its most effective when least accessible to observation, to actors and observers alike, thereby presenting empirically minded social scientists with a neat paradox’.Footnote 51 Hence what we look for are (following Lukes) observable mechanisms, relations, characteristics, and phenomena of power that can only be accounted for by resistance to exercises of power by external actors. While it is a challenge to get ‘behind the screen’ to uncover what James Scott has called the ‘hidden transcripts’, resistance by local actors does leave tangible and observable traces in various interactions and outcomes. Our expectation is that the outcomes in these issue areas do not emerge solely from an overt bargaining game embedded in peace agreements, but rather through the deployment of long-term and everyday forms of power/resistance that may ultimately thwart the aims of the international peacebuilding community, bending and fusing institutions and programmes to the purposes of local power-holding actors.

The analysis of the six areas builds on various sources of empirical data covering a wide range of national and international actors, allowing one to trace multiple and entangled power and resistance dynamics over more than a decade. The data notably includes three sets of semi-structured interviews conducted in 2008, 2012, and 2017 in Burundi with local managers of SSR and DDR processes (six interviews), with Burundian male and female political leaders and elected representatives (nine interviews), and with leaders of Burundian civil society organisations (11 interviews), respectively; a series of focus groups conducted in 2011 with both Burundian male and female (former) combatants (18 participants in total); and observational data collected via regular visits to the country since 2008. All interviews included open-ended questions, whose focus was adjusted depending on the identity of the interviewees: interviews with local participants or managers of DDR and SSR focused on the precise way in which ex-combatants were oriented towards different reintegration streams, and the mechanics of the programmes; interviews with political leaders and elected representatives included topics such as peacebuilding priorities in Burundi, or on peacebuilding's success; and interviews with leaders of civil society organisations focused on the participants’ involvement in national or international dialogue and mediation processes, or the problems and obstacles encountered in their everyday peacebuilding activities. The interviews’ lengths ranged from one to four hours, and all but one were taped or carefully noted. The focus groups with former combatants lasted between three and four hours each, and were dedicated to the combatants’ experiences with DDR and SSR processes, with a particular focus on reintegration options. In addition, various official reports and documents were collected, such as the Arusha Accords, the texts of the 2005 and 2018 Constitution, political declarations by the Burundian government, UNHCR, OCHA, and EU-produced reports on peacebuilding in Burundi, including documents on the Peacebuilding Framework for Burundi. Following a generally critical discourse analysis approach, these documents and interviews were used to map both practices and representations of peacebuilding in Burundi, as well as to uncover the dynamics of power/resistance that have been at play in the design and implementation of peacebuilding programmes.Footnote 52 In addition, these documents informed us on how peacebuilding in Burundi was designed, framed, and understood, how its progress was assessed, and how the major international and national peacebuilding stakeholders interpreted the various setbacks and challenges that their initiatives had to face. Finally, publications such as annual reports, online newspaper articles and blogs were used to document the discourses of international and national NGOs and civil society actors on peacebuilding in Burundi, and on reforms and political trends since 2000.

Political representation, power sharing, and ethnic quotas

The political aspects of the Arusha Accords introduced ethnic quotas, power sharing, and restrictions on ethnically-based parties, which have been described as crucial to Burundi's postconflict stabilisation.Footnote 53 The quotas were intended by the international community to prevent either Hutu or Tutsi from fully controlling state institutions, as had happened on several occasions in Burundi's past, and to diminish the salience of ethnic identities in politics – a clear illustration of institutional power with undertones of productive power. It took five years to negotiate the 2005 Burundian Constitution, and the CNDD-FDD (the current ruling party, majority Hutu) initially overtly opposed the introduction of a quota system, but eventually acquiesced in a system of quotas for the National Assembly, ‘composed of at least one hundred deputies at the rate of 60% Hutu and 40% Tutsi, with a minimum of 30% of women, elected by direct universal suffrage for a mandate of five years and three deputies from the Twa co-opted ethnicity conforming to the electoral code’.Footnote 54 Under pressure from the international community, the Arusha peace agreement also established quotas in the police, the army, at the communal level, and in public institutions, and qualified voting arrangements also provided a minority veto over certain issues.Footnote 55

Resistance to this exercise of institutional power shifted to the overt level after 2005, and formal compliance with the quotas masked other political manoeuvres, mainly involving the co-optation (via promises of benefits) of Tutsis from minor parties into the CNDD-FDD machinery.Footnote 56 After a few years of relative compliance, the past decade saw gradual erosion away from quotas and more generally from the constitutional architecture created by the Arusha Accords, including through slow or non-implementation of specific constitutional provisions concerning oversight and accountability mechanisms.Footnote 57 The decision of the late President Pierre Nkurunziza to run for a third term, which was interpreted by many observers as being in contradiction with Article 7(3) of the Arusha Accords, was, for instance, approved by the Burundian Constitutional Court in May 2015.Footnote 58 It is important to note that Nkurunziza's political party, the CNDD-FDD, did not negotiate the Arusha Accords and although it joined in 2003 it has never wholeheartedly supported it. In that sense, the hostility towards ethnic quotas increasingly displayed by the Burundian government can be interpreted as part of a broader resistance to the postconflict order created in 2000.

Concretely, resistance to ethnic quotas moved from covert to overt over time, and has followed two main lines. First, at the discursive level the Burundian government has reiterated that ethnic groups have been invented by colonial powers in order to divide Burundians, and that people should be nominated or elected according to their merits and not to their ethnicity – thus overtly challenging the externally-exercised productive power and the political subjectivities that underlie the quota system.Footnote 59 According to the government, public opinion generally favours ending the quota system, as well as other mechanisms enshrined in the Arusha Accords. In 2015, a National Commission for Inter-Burundian Dialogue (CNDI) was established to evaluate the Arusha peace agreement, and after conducting an opinion survey, the CNDI concluded that Burundians want ‘the Constitution to override the Arusha Peace Agreement’,Footnote 60 although the methodology and details of the survey have not been revealed, shedding doubt on its results. Second, as an overt expression of resistance to externally exercised institutional power, the government argues that ethnic quotas were never meant to endure since their maintenance was always meant to be reviewed, and that the Arusha Accords set the basis for a transition period, not for a permanent political system.Footnote 61 Hence, the government pushed for institutional change via a constitutional revision, leading to the adoption of a new Constitution in 2018. In its Article 289, the new Constitution gives the Senate five years, instead of an open time frame as in the previous Constitution, to decide whether to keep or give up ethnic quotas in institutions. In addition, the new Constitution also extends quotas to the judiciary, which was not the case under the previous one.Footnote 62 Other more fine-grained constitutional changes have undermined minority protections and strengthened presidential power – a clear subversion of Arusha. In an interesting attempt to instrumentalise what it sees as an externally imposed rule, the Burundian government has also used ethnic quotas as a tool against ‘international interference’, and in particular against international NGOs, by requiring them to declare the ethnicities of their Burundian employees, and to respect constitutional quotas.Footnote 63 In response, and illustrating how ethnic quotas have become the focus of multileveled power struggles, in 2018 around thirty international NGOs chose to close their operations in the country, thereby removing $280 million from the Burundian economy.Footnote 64

Land reform

The resolution of land-related conflicts, as well as the need for a land reform, was identified as essential for postconflict stabilisation in the Arusha Accords, and was largely supported by external peacebuilders, as an exercise of institutional power designed to reduce inequality and conflict, and redress rights.Footnote 65 Land is a source of wealth (or subsistence) and power for Burundi's largely rural population, and access to land has long been a source of conflict, with three-quarters of court cases dealing with land conflicts.Footnote 66 The return of internally displaced persons and refugees after the end of the conflict exacerbated these tensions at the local level.Footnote 67 One of the main dispositions of the Arusha Accords had been to establish a National Commission for the Rehabilitation of Sinistrés (CNRS), as well as a Sub-Commission of the CNRS with the specific mandate of dealing with issues related to land. This Commission Nationale des Terres et Autres Biens (National Commission on Land and Other Assets, CNTB), finally established in 2006 after years of covert resistance on the part of the Burundian government, has been at the centre of constant and numerous controversies, and the law governing this institution has been amended four times between 2009 and 2019, highlighting the fact that resistance has been substantial at the legislative level. Other provisions in the Arusha Accords that were designed to give compensation and/or indemnification to those who could not recover their land, such as the creation of a National Fund for Sinistrés,Footnote 68 were never implemented, representing another form of covert resistance to the socioeconomic implications of land restitution policies.

Most of the controversies focus on who should be included in the category of sinistrés, defined in the Arusha Accords as including ‘all displaced, regrouped and dispersed persons and returnees’, and how they should be compensated for their lost properties.Footnote 69 Considering the numerous episodes of post-independence violence in Burundi, each of which generated waves of forced displacement, the sinistrés also include people who had been forcefully displaced before the 1990s, and who belong to groups sometimes considered as responsible for past outbreaks of mass violence. In the early years of its functioning, the CNTB upheld a sharing policy, whereby land was shared between returnees and residents. However, these rulings have often been contested by individuals through regular court cases, and consequently overturned, highlighting a tension between the understanding promoted by the institutions born of the Arusha Accords, and the national courts’ interpretations.Footnote 70 In addition to this normative and covert resistance to the institutional power externally exercised by the international community through the Arusha Accords, there are also indications that the Burundian government and political elite are using the CNTB for their own political purposes. After a few years and a change in leadership, the CNTB started issuing rulings that political opponents describe as favouring the Hutu and/or CNDD-FDD allies, thus resisting efforts to reshape the institutional mechanisms for ensuring fair access to land.Footnote 71

As in the case of ethnic quotas, both the government and the CNTB leadership reject responsibility for these disputes, and accuse the international community and the Arusha Accords of setting up norms that are impossible to implement in Burundi, because of its long history of conflicts, and because of complex patterns of relations at the local level. Resistance to an externally imposed land reform has, however, so far remained covert and/or normative, stopping short of attempting to change or reform the institutions born out of the Arusha Accords. In a press conference held by the CNTB president on 29 December 2011, he declared: ‘Believe me, it is not the CNTB's fault, if all the laws without exception, be they from the UN or those deriving from the Arusha Accords, say that the returnees must imperatively be re-established in the property rights from which they have been unjustly deprived.’Footnote 72 It is also worth noting that at the local level land issues are often governed by custom, for instance by the informal practice of only sharing or passing on land to male members of a family. As such, normative resistance was also triggered by a clash between traditional practices and values, and norms established in the Arusha Accords or upheld by the CNTB.

Human rights promotion

Signatories to the Arusha Accords committed to respect international human rights instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenants on Human Rights, or the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, all of which form part of the peacebuilding efforts to reshape relationship between the state and citizens, in line with liberal ideas of political identity and individuals as rights bearers. In subsequent years, however, it became clear that these commitments were hardly respected, in a context where parties hostile to the agreement were still active, and where disappearances, arbitrary arrests, kidnappings, and extra-judicial killings remain common.Footnote 73 At the national level, the Burundian government initially exerted relatively covert resistance to the request to respect human right norms, mainly through delays in implementation. A Commission Nationale Indépendante des Droits de l'Homme (National Independent Human Rights Commission, CNIDH) was eventually created only in 2011. Initially active, including in monitoring the Burundian government's actions, the CNIDH has become progressively less effective since 2015, and has turned a blind eye to human rights violations. When, in 2017, the UN Commission of Enquiry on Burundi called for the International Criminal Court (ICC) to launch an inquiry into human rights violations in Burundi, the CNIDH vehemently opposed its conclusions, demonstrating fealty to political actors rather than human rights instruments.Footnote 74 Since 2015 the CNIDH seems to have completely lost its independence, and to have been instrumentalised by the government.Footnote 75

The human rights situation has further degraded since 2015, with multiple cases of human rights violations, especially with a political dimension. Political opponents have been particularly targeted, as well as people returning from refugee camps, especially from Tanzania. Returnees are seen as potential traitors, and are frequently harassed by local authorities and the CNDD-FDD militarised youth branch, the Imbonerakure.Footnote 76 Human rights violations are particularly numerous in rural areas, but they also occur in cities and in Bujumbura, in particular. The activities of civil society organisations headquartered in Bujumbura are closely monitored by the government, and since 2015 repression against human rights organisations has become systematic, with many human rights advocates having gone into exile, disappeared, or been assassinated – more than 156 disappearances have been recorded by the UN since 2016.Footnote 77 Various basic democratic liberties, such as freedom of expression, opinion, information, association, meeting, and even of circulation have been seriously limited. These violations have occurred in a context of general impunity and dysfunctions in the legal and judicial systems. Impunity is fed by a fear of reprisal and by very low levels of reporting, as perpetrators are reported to include state agents such as police officers, soldiers, but also administrators in provinces, communes, and collines. Footnote 78

While the human rights abuses that have occurred in the context of the 2015 political crises can hardly be interpreted as resistance to external peacebuilding, the open rejection by the Burundian government of any attempt by the international community to monitor the human rights situation clearly does represent overt resistance to the productive power of human rights norms. At the institutional level, the government has reaffirmed its power by refusing to work with the UN Human Rights Council, and has overtly resisted cooperating with the Commission of Enquiry on Burundi established in 2016. In 2018, the Burundian government declared its three commissioners persona non grata in Burundi, and rejected the Commission's report as ‘defamatory’, ‘deceitful’, ‘biased’, and ‘politically motivated’.Footnote 79 Most importantly, after the ICC announced a preliminary examination of the situation in Burundi in April 2016, the Burundian government withdrew from the Rome Statute in 2017. The government motivated its decision using a strong anti-colonial and anti-Western discourse, destined to rally support in the region and in the Global South more generally: ‘The ICC has shown itself to be a political instrument and weapon used by the west to enslave.’Footnote 80 The government also refused to allow the visit of the UN Sub-Committee on Prevention of Torture in 2018, and over the past years it has constantly failed to send reports concerning the elimination of racial discrimination, children's rights, the use of torture, and so on. The international community has been powerless to effect change in any of these situations, despite having imposed limited sanctions against key individuals, and both its bargaining and institutional power have proven to be weak. Interestingly, the three cases detailed above show that the Burundian government tends to refer to different spatial reference points when exercising its power to overtly or covertly resist externally imposed policies. On ethnic quotas, land reform, and human rights promotion it has respectively referred to the national, local, and regional/continental scale, revealing its ability to deftly play on multiple narratives and ‘systems of relevance’Footnote 81 to exercise its own power against external intervention.

Security sector reform (SSR)

Control of the security sector lies at the heart of political power in authoritarian states, and Burundi has been no exception. For this reason, the Arusha Accords and subsequent programmes focused heavily on disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration of armed groups into newly reconstituted security forces, and embarked on an extensive reform of the security sector itself. The goal was to remove and insulate the armed forces from its traditional role as a tool of the regime, and to diminish its sectarian nature. During the 2000s, the World Bank made Burundi one of the countries eligible for the Multi-Country Demobilisation and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) for disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR). The EU and a host of bilateral donors also played significant roles in SSR programming.Footnote 82 DDR was not seen as an isolated element that concerned armed groups, but was rather part and parcel of efforts to re-engineer a new security sector, including the creation of the Burundian National Police (BNP), the resizing of the armed forces to 25,000, and the demobilisation of a number of former armed combatants. While early assessments of SSR were largely positive, at least in the sense that the armed forces successfully integrated former combatants and did not overtly intervene in politics, these conclusions clearly overestimated the influence external actors could have on the norms and practices of an institution central to the exercise of power, and missed the more covert forms of resistance to the aims and preferences of external actors.Footnote 83

From the outset, the ethnic balance of the security forces was impossible to achieve. However, contrary to the areas that we have examined so far, resistance to these reforms did not primarily originate from the Burundian government, but from a set of actors located within the Burundian security sector itself. As of 2008, only 30 per cent of senior army commanders were Hutu, and almost one-third (31) per cent of senior commanders hailed from one region (Bururi), the province from which the first three post-independence presidents came (ruling from 1966–93), and the heartland of CNDD-FDD power.Footnote 84 Such concentration testified indirectly to the persistence of strong shadow networks, which manifested themselves subsequently in factionalism among the officer class, including reciprocal assassinations and power struggles, with the military emerging by 2020 as ‘a central power broker’ in national politics.Footnote 85

The creation of a national police also represented a challenge, as Burundi had previously only a francophone style gendarmerie. The Burundian National Police (BNP) grew from 2,000 in 2000, to 20,000 police officers in 2007, with the rapid induction of ex-combatants, many of whom preferred to join the national police over either the armed forces or civilian demobilisation.Footnote 86 This choice made by individual combatants, and unforeseen by the international community, appears counter-intuitive given that the army provides for the minimum basic needs (food and shelter) of its soldiers, as well as relative stability. Yet joining the police appeared more attractive, apparently because the police enjoyed greater rent-seeking opportunities through their ability to extort funds from the local population with minimal oversight.Footnote 87 In addition, the best trained and connected ex-combatants were brought into the army, and the least disciplined, worst connected, and least well trained went into the police with little or no vetting or oversight of the selection process, or training for civilian policing tasks.Footnote 88 As a result, the BNP is one of the main sources of insecurity in Burundi, and a parallel chain of command, related to the CNDD-FDD and in charge of repression against the political opposition, also exists within the police.Footnote 89 In addition, the National Intelligence Service (Service National de Renseignement, SNR), the state intelligence service of Burundi, operates outside of any SSR or civilian oversight, and remains a potent political tool that has been implicated in repression and extra-judicial executions of political opponents, highlighting covert, if not overt, resistance of the Burundian government to the aims of the externally-led SSR.Footnote 90

Reforming the Burundian army has been equally a site of resistance by military elites, as the army has traditionally been the primary source of power and control, as well as an instrument of specific factions – a role that it has reassumed in recent years.Footnote 91 The SSR process was supposed to reduce the national army to 25,000 soldiers, and not surprisingly there was covert resistance exerted by army officers to the rapid downsizing amidst suspicions that the army ranks were filled with ‘phantom soldiers’ whose presence allowed officers and high ranking officials to collect salaries and otherwise pocket allocations (food, materiel, etc.) destined for soldiers ostensibly under their command. In addition, and despite the careful engineering of ethnic quotas, the CNDD-FDD has been a major shadow presence that ‘controlled forces of ex-combatants who still needed to be demobilized and reintegrated’, allowing it to distribute weapons to its youth movement the Imbonerakure, and to orchestrate political intimidation and repression against pro-democracy actors.Footnote 92

The reintegration programme was also, at the micro-level, the target of a hidden form of resistance on the part of demobilised combatants themselves. The World Bank plan for Burundi laid down several conditions for reintegration packages. The total value of the package was to be 600,000 FBU (about 600 dollars) per ex-combatant, but it could not be given in cash, used to build a house, or to buy land.Footnote 93 Each of these conditions had a specific rationale for the World Bank: the first two were considered not to result in durable income streams (and hence inconsistent with the goal of the programme) and the last was excluded because of the feared distortive and conflict-generating effects of land purchases.Footnote 94 The individuals who were demobilised were the least well educated former combatants, and hence less likely to have the social capital required to be active participants in the patrimonial networks that characterised the armed forces and police.Footnote 95 Training options included education, vocational skills training, entrepreneurial training, or income-generating activities. In practice, ‘of the 25,000 ex-combatants who have been reintegrated the vast majority have chosen to engage in AGR [income generating activities]’.Footnote 96 In an environment where more than 75 per cent of the population lives off subsistence agriculture, the creation of a cadre of shopkeepers was at odds with socioeconomic realities. Instead ex-combatants quickly monetised their reintegration package, setting up a fictitious small business, stocking it with goods that could then be liquidated for cash. It was easy to determine exactly how many cases of beer or cartons of cigarettes could be acquired for 600,000 FBU, and in the most straightforward monetisation wholesalers simply certified that goods had been delivered, received compensation from the programme, took their cut, and passed the cash to the ex-combatants.Footnote 97

Actors at all levels resisted in various ways the objectives set by the international community for DDR and SSR. At the micro level, DDR recipients had a clear set of material aims, and they did not agree with the World Bank's vision. They operated within the rules of the game by selecting one of the options (AGR), and cashed out as a form of covert resistance. At the meso-level, although a national police force was created that met the explicit aims of the external interveners, it did not fully succeed at its principal public mission of providing security. Rather, it has been a source of endemic insecurity – both from the predatory behaviour of individuals, but also the instrumental use of the institution as a tool of power for the state elite.Footnote 98 At the macro level, opposition to exercises of institutional power was not manifest publicly but was no less effective, as power holders shaped outcomes in ways that met their aims – consolidating control, using the armed forces as an arm of political power, and maintaining their shadow authoritarian practices.

Gender mainstreaming and gender equality

Gender equality was promoted as a key element of postconflict stabilisation and peacebuilding in the Arusha Accords, and can be seen as an exercise of productive power designed to empower women as political and social actors, and reshape social roles and norms. The mainstreaming of gender issues in the agreement was largely initiated by Burundian women's movements that joined the last rounds of negotiations in Arusha, and built on the support offered by international mediators.Footnote 99 However, progress towards gender equality has been slow, in particular in the political field and with regards to the fight against gender-based violence. While there is some evidence that local actors do not necessarily consider their reluctance to implement gender equality as resistance (thus representing normative resistance), most gender mainstreaming initiatives have faced both normative and covert resistance. Many laws, for instance regarding inheritance or land ownerships, retain discriminatory provisions regarding women, thereby signalling a certain reluctance of legislators to implement gender equality objectives. Likewise, discriminatory customs (such as equal access for women to education or to the justice system) are widespread, in particular in rural settings, where they also tend to be upheld by traditional authorities such as the Bashingantahe, local justice councils consisting of wise elders.Footnote 100 At the political level, progress has been made towards the election of women at the Assembly and the Senate, and their participation in the national government. But at the local level, fewer than 10 per cent of chefs de colline are women.Footnote 101 This is usually explained by cultural and social obstacles facing female candidates, such as pressure from relatives, difficulties to gather the necessary funding for campaigning when they are not backed by a major political party, as well as a general sentiment, publicly articulated, especially in rural areas, that women should stay clear of politics. Politics remains largely a men's realm; elected or nominated women are often obliged to follow the party line and are rarely allowed to make their own decisions.Footnote 102 Not surprisingly, cultural conservatism regarding gender equality is shared by some women's civil society organisations that argue that women should only be active on ‘women's issues’, promoting a different understanding of gender equality – and political identity – than the one advanced by the international community.Footnote 103

Another area where progress has been limited is the fight against gender-based violence (GBV), which implicated understandings of gender relations, as well as the boundary between the public and private sphere, both key elements of liberal subjectivities. While gender focal points have been created in many police stations, and a law on the prevention, victims’ protection, and repression of GBV was adopted in 2016, rates of GBV against women have remained particularly high.Footnote 104 Although police officers working in gender focal points received specific training and demonstrate a generally higher awareness of GBV, research shows that local practices mostly remain impervious to liberal norms. Corruption, pressure, amicable arrangements between families to redress the crime, ignorance of the law and procedures, interference from local politicians, lack of professionalism and of funding impede the prosecution of GBV cases.Footnote 105 In addition, most police officers working in gender focal points are men, which constitutes another obstacle for victims and survivors.Footnote 106 These forms of normative resistance do not originate from one actor only. They are deeply embedded in local norms and practices, and impede efforts to reshape gender relations in what remains a largely patriarchal society.

Similarly, DDR programmes implemented since December 2004 largely overlooked gender issues. Many former female combatants explain for instance that commanding officers would often delete female combatants’ names from the lists of those who had to be demobilised, and they could only access DDR programs in exchange for sexual favours or a payment.Footnote 107 As underscored by Nina Wilén, local elites’ tendency to view gender as an ‘add-on’, and not as a central disposition of peacebuilding policies, is one of the major obstacles faced by gender mainstreaming.Footnote 108 So if some timid progress in terms of gender equality can be identified at the legislative level, it faces considerable covert and normative resistance at the societal level, especially in rural areas, as it threatens to disrupt pre-existing power relations and customs.

Transitional justice

Transitional justice figured high on the international community's agenda for Burundi as a way to foster national reconciliation and deal with the past and more subtly, as a means of reconfiguring power relations and endowing citizens (not only victims and survivors) with hitherto inconceivable political rights and identities.Footnote 109 The Arusha Accords established specific terms for transitional justice, making provisions for the establishment of a truth and reconciliation commission, an international judicial commission of enquiry, and possibly also an international criminal tribunal. The foreseen transitional justice mechanisms thus included both criminal and restorative instruments, and were initially conceptualised as a cooperative effort between the Burundian government, civil society, and the UN. However since 2000 these mechanisms have been resisted covertly (and later overtly) by both governmental and civil society actors, seriously hampering their implementation and challenging the premises of the peacebuilders’ exercise of productive and institutional power.

Legislation to establish a national truth and reconciliation commission was adopted by the Burundian Parliament in December 2004, but covert resistance by the Burundian government to the terms set by the Arusha Accords meant it took ten years to establish a Commission Vérité et Réconciliation (CVR).Footnote 110 Although the UN sent a delegation to Burundi in 2006 to accelerate the establishment of the CVR and of an international judicial inquiry (as foreseen in the Arusha Accords), negotiations were suspended in 2007, after an agreement was reached to organise national consultations on transitional justice.Footnote 111 These public consultations were held during the second half of 2009, with a report released in 2010.Footnote 112 Time devoted to these consultations was short, and only 3,887 people participated (out of 4,837 who were invited),Footnote 113 allowing the government to control and limit the process. Fourteen years after Arusha, the CVR eventually began its work. Eleven CVR commissioners were chosen from 725 nominations, but opinions voiced during the public consultations favouring the nomination of international commissioners, or a strong participation of civil society representatives, were ignored by the government.Footnote 114 This suggests that the government wished to further limit the influence on transitional justice mechanisms of the international community and of the Burundian civil society, both suspected of harbouring liberal views on the matter.

The delayed establishment of the CVR can also be explained by disagreements between the Burundian government and the UN on the aims and scope of transitional justice, but also by the fact that the international community wanted to make sure that the conditions for transitional justice were ripe, and that they did not clash too openly with the Burundian elites priorities.Footnote 115 As explained by Vandeginste, both the Burundian government and the international community have always favoured peace and stability over justice in Burundi, which has resulted in a ‘coalition for forgiveness’.Footnote 116 As a consequence, the international community did not always push for swift action, an attitude that was skilfully exploited by the Burundian government.Footnote 117 Within the international community, the UN pushed the hardest for the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms, and as a result, it is mostly between the Burundian government and the UN that clashes happened. For instance, the UN and the Burundian government disagreed on the investigative autonomy of the prosecutor of the special tribunal to be created, whose independence the UN wanted to guarantee.Footnote 118 Most importantly, disagreements centred on the issue of amnesty. The Burundian government favoured a forgiveness approach, whereas the UN recommended that no perpetrator of serious crimes should be granted amnesty or forgiveness. International as well as national laws forbid amnesty for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, and in the Arusha Accords, the scope of amnesty is also strictly defined: ‘[a]mnesty shall be granted to all combatants of the political parties and movements for crimes committed as a result of their involvement in the conflict, but not for acts of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes, or for their participation in coups d'Etat.’Footnote 119

For the Burundian government, the problem was that many perpetrators of serious crimes were to be included in the power sharing government, the police and the army. Allowing their prosecution risked endangering these plans, and preventing their return from exile. In order to avoid this, the Burundian government used several strategies to circumvent the amnesty prohibition supported by the UN: first, it granted temporary immunity against prosecution for politically motivated crimes, a measure that had been foreseen in the Arusha Accords;Footnote 120 second, it delayed the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms; and third, it imposed limits on the jurisdiction of the national justice system, arguing that it was up to the CVR to determine which crimes an amnesty law would cover.Footnote 121 The government's overt resistance to the pace and framing set by the international community also relates to other factors, such as the fact that one of the main rebel movements, the Palipehutu-FNL, only signed a peace agreement in 2006. The ongoing conflict was likely, in the eyes of the government, to impede the work of the CVR.Footnote 122 But as David Taylor explains, resistance around the establishment of the CVR can also be explained by the government's wish to control the narratives about the conflict, especially since the proposed mandate of the CVR included ‘a writing of the entire history of Burundi from independence to 2008’.Footnote 123

Resistance was also initiated by civil society organisations, against both transitional justice models favoured by the UN,Footnote 124 and those put in place by the Burundian government. While the Burundian government was delaying the establishment of the CVR, the UN turned its attention to civil society initiatives in the field of transitional justice, for instance through the Transitional Justice Unit (TJU) of the UN Office in Burundi (BNUB).Footnote 125 However, civil society organisations sometimes overtly resisted UN views, notably by promoting bottom-up approaches of transitional justice, instead of top-down ones, and by replacing the principle of reparations by that of the promotion of ‘positive relations’ between victims and perpetrators – a form of overt resistance to productive power.Footnote 126 In parallel, these civil society groups sought to hold the Burundian government accountable on transitional justice issues, and have been protesting against the government's instrumentalisation of the CVR for electoral purposes, for instance by using past massacres to reinforce ethnic divisions.Footnote 127

Conclusion: Resistance is not futile

The above analysis illustrates the diverse ways in which local actors deploy different forms of power to resist attempts by external actors to reshape political, social, and economic relations through peacebuilding programmes and policies. On issues central to entrenching CNDD-FDD rule, resistance has moved from covert to overt forms, in particular regarding ethnic quotas and human rights issues (institutional and productive power). On other issues such as land reform and gender equality, covert (and occasionally normative) resistance seems to have intensified over time. For SSR and transitional justice, the interests and actions of the most engaged local actors (government, security sector, and civil society organisations) do not always coincide, thus giving mixed results. But overall these resistance efforts have largely undermined, hollowed out or discarded key elements of the liberal peacebuilding project in Burundi, with the result that – after twenty years – Burundi has reverted to a form of authoritarian rule that characterised much of its post-independence existence.

In this light, the two decades of intense involvement by external actors is merely an episode in a more complex story of local political rivalries and power struggles between and within groups. External peacebuilding often attempts to treat these struggles as distinct from state-building and governance writ large, and to regard local elites, including military personnel, senior administrators, and some leaders of civil society organisations, as neutral agents distinct from purely political actors. Yet all, and especially elite, actors are embedded in dense local networks of power, and the evidence above suggests that the system they defend is neither a pure reproduction of a neo-patrimonial system, nor a straightforward and unconditional adoption of international norms. International norms and programmes are harnessed in local and national power struggles, in order for individuals and elites to secure positions and power in the postconflict order. The upshot is that ‘encounters between international, regional, and local actors have produced governance arrangements that are at odds with their liberal and inclusionary rhetorics. Paradoxically, the activities of international peacebuilders have contributed to an “order” in Burundi where violence, coercion, and militarism remain central.’Footnote 128

From our perspective, however, there is nothing paradoxical about this result: for some local actors at least, and in particular for local political elites, it means that their resistance has been effective. As Peter Uvin and Leanne Bayer put it: ‘international aid … entrenches local elites … at the expense of the other institutions of state and society … International aid entrenches not only local elites, but also local systems of clientelism and, more generally … the “political marketplace”.’Footnote 129 Although overt resistance to liberal peacebuilding prescriptions has become more prominent over time, even from the outset of the peace process, covert and sometimes normative, long-term and everyday forms of resistance to the exercise of structural and productive power systematically thwarted the goals of peacebuilders’ programmes, often while working within the institutional and programmatic confines dictated by the liberal peacebuilders.

The more general conclusion is that scholars need to be more attentive to the interplay of different forms of power/resistance in peacebuilding practices, and in particular the different temporalities over which forms of resistance unfold. While exercises of bargaining power and thus overt resistance may characterise the negotiation of peace agreements, or the initiation of particular programmes and policies, institutional and productive power are embedded also in the logic of liberal peacebuilding (and all external interventions), and in attempts to reshape the space within which politics is conducted, the norms that govern it, and the subjects duly empowered to participate. Different forms of resistance to these exercises of power unfold on different time scales, and superficial early successes at peacebuilding are often undermined first by covert, and subsequently by more overt or even normative, resistance. Which forms of resistance are deployed by which local actors and on what issues depends on their positionality and objectives, and will change over time. But the balance sheet for peacebuilding over the past two decades suggests that external actors seldom exercise institutional and productive power in an enduring fashion, and that local actors are highly capable of hollowing out these efforts through diverse forms of power/resistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the numerous interviewees and contacts in Burundi who facilitated this research, colleagues at Manchester University, Oxford University and at ISA conferences for comments on the conceptual framework, and the anonymous reviewers of the journal for helpful suggestions.

Élise Féron is a Docent and a senior research fellow at the Tampere Peace Research Institute (Finland). She is also invited professor at the University of Louvain (Belgium), the University of Turin (Italy), Sciences Po Lille (France), and the University of Coimbra (Portugal). Before moving to Finland, she held permanent positions at the University of Kent (UK) and at Sciences Po Lille (France). Her main research interests include conflict-generated diaspora politics, gender and conflicts, as well as the multiple entanglements between conflict, violence, and peace. Author's email: Elise.Feron@tuni.fi

Keith Krause is Professor of International Relations at the Graduate Institute (Geneva), and Director of its Centre on Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding (CCDP). Until 2016, he was Programme Director of the Small Arms Survey. Professor Krause obtained his DPhil in International Relations in 1987 from Balliol College, Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. His research concentrates on critical security studies, political violence, postconflict peacebuilding, and security governance. Author's email: keith.krause@graduateinstitute.ch