I. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was neither the first nor the deadliest pandemic faced by modern-age humanity. However, it was the one that transformed our understanding of the state’s role during a public health crisis. It also introduced an array of unprecedented policy tools: ever-stricter travel restrictions, lockdowns and closures of whole branches of the economy.

Together with these new goals and tools, one could expect appropriate reflection on their effective deployment. On the one hand, evidence-based policymaking seems to be the gold standard of such high-stakes policy interventions. On the other hand, the dynamic of the pandemic – as well as the intertwined processes of scientific research and organisational learning – complicated efforts to rationalise anti-pandemic policies.

Moreover, countries differ in terms of the decision-making processes they implemented and their legal frameworks governing anti-pandemic policy implementations. At one extreme, Sweden conformed to the pre-COVID-19 legal framework, exemplified by famous remark from its epidemiologist-in-chief, A. Tegnell: “The Swedish laws on communicable diseases are mostly based on voluntary measures … This is the core we started from because there is not much legal possibility to close down cities.”Footnote 1

At the other extreme, Austria implemented perhaps the first COVID-19-related constitutional amendment.

Poland, a gradually illiberalising European Union (EU) Member StateFootnote 2 (1) firmly refused to evoke the constitutional state of emergency, (2) passed an ad hoc COVID-19 law of 2 March 2020 – the backbone of its crisis management – and (3) passed numerous COVID-19-labelled amendments to other laws (while the state of emergency is, by definition, temporary, these changes are not).

To gauge how this response squared with the principle of legal certainty, it is enough to say that just four months since its passing of the COVID-19 law of 2 March 2020, the law already includes Article “15zzzzzze” (pasted between Articles 15 and 16, with subsequent letters denoting articles added such as 15a, 15b … 15za, 15zb … 15zza and so on).

What is more – and crucially for this article – most of the restrictions binding citizens and businesses were not introduced by the COVID-19 law itself but by almost weekly executive act amendments.

This article analyses the regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) accompanying sixty-four executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions in Poland’s first year of the pandemic (March 2020–March 2021). To this end, the study utilises the so-called scorecard methodology, which is popular in RIA research. At this point, the following hypothesis can be set forth: the ad hoc pandemic management process crowded out the law-making process and its evidence-based policy tools. In other words, genuine decision-making moved outside of bureaucratic law-making (including RIAs), rendering it mere window-dressing.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section II briefly presents the Polish anti-pandemic policy mix as compared to other EU jurisdictions. Section III introduces the specific crisis-response governance framework set up in early 2020 and links it to the RIA process in Poland. Section IV outlines the criteria behind RIAs evaluation and describes the utilized scorecard. Section V summarizes results while section VI concludes.

II. Severity of the Polish COVID-19 response as compared with those of other EU jurisdictions

To provide a background to the analysis of the RIAs accompanying Polish executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions, it is useful to illustrate the general severity of the Polish COVID-19 response as compared with the typical response of other EU Member States. To this end, the Oxford University COVID-19 Government Response Stringency IndexFootnote 3 for the EU-27 is plotted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index for Poland as compared to the other EU-27 Member States (January 2020–March 2021).

Fifteen “typical” EU Member States are the 25th–75th percentiles – namely, the range between the seventh and twenty-first Member States – as ordered from the lowest to the highest stringency index level.

Note that the timing of subsequent COVID-19 waves differed from country to country, which is not reflected in this figure. Therefore, the presented data should be interpreted with caution.

Source: Hale et al, supra, note 3.

Although the timing of the initial COVID-19 outbreak – as well as subsequent waves – differed from country to country, three general observations can be noted.

First, during the first wave (February–May 2020), the pace and severity of restrictions introduced in Poland broadly followed the response of the majority of EU countries (for details on the regulatory actions introduced in Poland during the early phase of the pandemic, see Gruszczyński et alFootnote 4 ).

Second, the presidential elections due in May 2020 (and postponed to late June and mid-July 2020) had been associated with a substantial loosening of restrictions, separating Poland from the EU “mainstream” and placing it in the low-stringency group of the EU Member States (from 18 September to 9 October 2020 Poland had the lowest COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index score across the EU-27).

Third, during the second wave of the pandemic in October 2020, Poland introduced a relatively severe lockdown, moving it into the high-stringency group (and it maintained this policy throughout the winter).

Therefore, it can be concluded that, during some periods, the Polish response was characterised by relatively high stringency, while during others it was characterised by relatively low stringency. As such, an amount of discretionary power had been wielded, which ought to have been based on a sound evidence base – which, in turn, ought to be present in the examined RIAs.

III. Decision-making processes and the regulatory impact assessments

As the Polish crisis response had been influenced by domestic decision-making (instead of merely following EU trends), it is important to examine the process underlying it. Specifically, one has to distinguish between (1) the ad hoc process established to counter the pandemic and coordinate the economic crisis management and (2) the pre-pandemic, well-established law-making process of issuing executive acts, including public consultations, intra-cabinet consultations and RIAs.

The ad hoc process had been conducted in the Chancellery of the Prime Minister and included the so-called Medical Council advising the Prime Minister.Footnote 5 Numerous accounts (including press conferences, during which new restrictions had been routinely announced) suggest that at least to some extent the decisions had been supported by the data on newly confirmed cases and their rolling weakly averages, as dramatic weekend effects manifested.Footnote 6

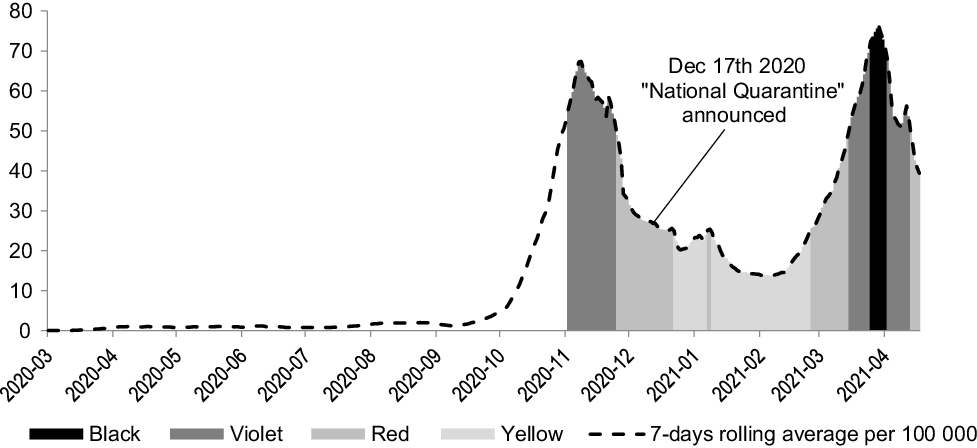

In particular, in early October 2020, on the eve of the second wave of the pandemic, the Polish Prime Minister embarked “on forward guidance”,Footnote 7 linking the rolling weekly average of newly confirmed cases to the colour-coded restrictions packages. Such a rule-based approach had been advocated on the grounds of introducing some predictability into the anti-pandemic policy, thereby reducing business uncertainty. However, as is plotted in Figure 2, this guidance quickly went out of fashion.

Figure 2. Newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in Poland and the implied colour-coded restriction packages.

Source: Data on COVID-19 cases from M Roser, H Ritchie, E Ortiz-Ospina and J Hasell (2020) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19), published online at OurWorldInData.org, available at <https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus>; colour-coded package thresholds as in the Prime Minister’s 4 November 2020 slideshow, available at <https://www.gov.pl/web/premier/nowe-kroki-w-walce-z-koronawirusem--ostatni-etap-przed-narodowa-kwarantanna>.

On the one hand, abandoning a rigid approach based on a single – and admittedly flawed – time series could be praised as escaping McNamara’s fallacy.Footnote 8 Indeed, administratively confirmed cases (1) represent only a tiny fraction of all cases, (2) are sensitive to the number of tests carried out and the pre-testing selection routines used and (3) are affected by behavioural patterns; for example, people with mild syndromes might be less likely to report them as the associated quarantine burden increases.

On the other hand, it can be seen that these decisions were based on some sort of discretionary process prone to cognitive biases (eg groupthink) and political pressures,Footnote 9 while various metrics were used for support rather than illumination – as in the case of the so-called “National Quarantine”Footnote 10 announced on 17 December 2020 to begin 28 December 2020 and last until 17 January 2021 (which included – among other things – a ban on leaving home on New Year’s Eve).Footnote 11 Consequently, when the newly reported cases rule suggested loosening restrictions, cross-country comparisons or healthcare capacity data (admittedly a much more appropriate metric) had been invoked.

According to the cabinet communications, the Medical Council should provide its expert judgmentFootnote 12 and the Council of the Ministers should decide on the scope of the restrictions. As indicated in Section I, the Polish ruling elite refused to invoke a constitutionally prescribed state of emergency. Instead, an ad hoc legal framework including one-off legislation as well as permanent amendments had been set up.Footnote 13

The Polish constitution of 1997 introduces the hierarchy of universally binding laws,Footnote 14 including (1) the Constitution itself, (2) ratified international treaties, (3) statutory legislation (passed by the parliament and signed into law by the president; in Polish, ustawa) and (4) executive acts, issued by the Cabinet or individual cabinet ministers based on explicit statutory authorisation (in Polish, rozporządzenie). According to the constitutional principles, the rights and obligations of citizens ought to be regulated at least on the level of statutory legislation, with executive acts being appropriate to regulate technical issues regarding the implementation of statutory legislation.

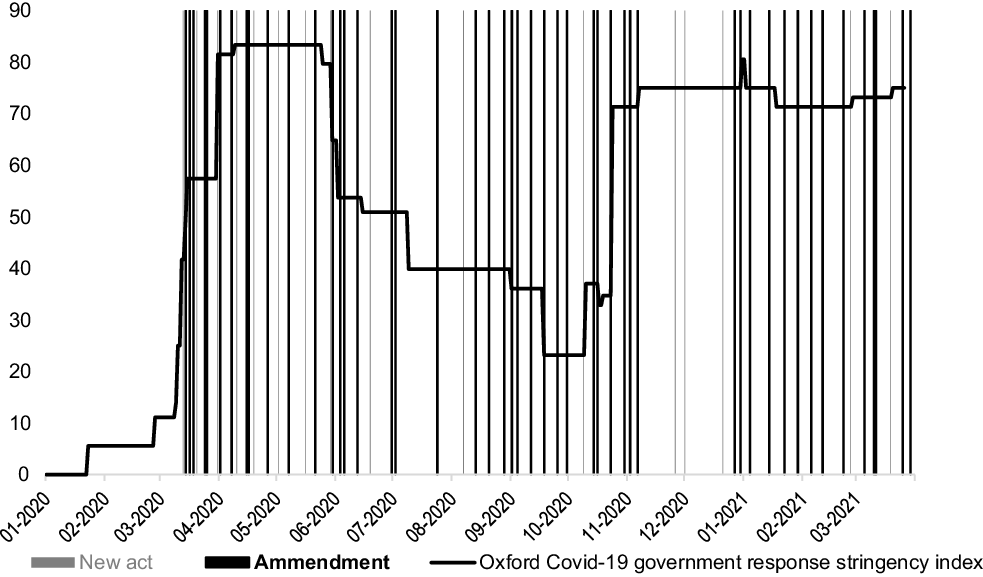

However, since the outbreak of the pandemic it was decided to introduce key restrictions via executive acts (on their timing and the stringency of the implemented measures, see Figure 3) – first issued by the Minister of Health and then by the Council of Ministers. This decision had been advocated based on the requirement for flexibility (which is hardly convincing given the speed of statutory law-making practised in Poland after 2015, such as during so-called judiciary reformsFootnote 15 ). However, this plain unconstitutionality backfired, as enforcement actions had been challenged before the courts.Footnote 16 Statutory provisions relating to the obligation to wear surgical masks had been introduced as late as 29 November 2020.Footnote 17

Figure 3. New executive acts (grey bars) and their amendments (black bars) over the January 2020–March 2021 period (COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index superimposed as a black line).

Sources: Hale et al, supra, note 3, and authors’ own work.

Leaving constitutionality issues aside, the law-making process of issuing executive acts had been well-established and regulated long before the outbreak of COVID-19.Footnote 18 It was designed to facilitate collegiality (intra-cabinet consultation procedures) and to achieve better regulation guidance on evidence-based policymaking (public consultations and RIAs).

Typically, the process is initiated by the appropriate minister submitting a draft of the normative text, an explanatory memorandum and a RIA to the consultations (public and internal). The agreed draft (or list of disagreements) is then submitted to the Permanent Committee of the Council of the Ministers (the so-called “little cabinet”) and, if appropriate, to other committees. Finally, the worked-out project is submitted to the Council of the Ministers. Notably, the so-called Government Law-Making Process is transparent (ie all submitted documents ought to be recorded and published on the InternetFootnote 19 ).

The RIAs of the executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions examined in this article represent part of this law-making process.

This brings us back to the distinction between (1) the ad hoc pandemic management and (2) the law-making process itself. In practice, these processes could be either integrated, parallel or one of them could dominate the other.

IV. Regulatory impact assessment quality measurement: methodology

To examine the RIAs accompanying the executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions, a “compliance test” assessing the RIAs’ formal compliance with requirements stated in laws, bylaws or guidelinesFootnote 20 was applied. Specifically, the “scorecard” methodology was used. Its application included two steps. First, the scorecard was designed (ie the set of questions regarding the RIAs’ contents), drawing upon the literature, the Polish RIA template and the unique context of the anti-pandemic policy response. Second, each of the sixty-four RIAs was assessed against such a benchmark.

1. The scorecard method of regulatory impact assessment quality measurement

The so-called scorecard method is by far the most popular approach in the RIA quality literature. Introduced by Hahn et al, it attempts to quantify the “quality” of RIAs, defined in terms of compliance with formal requirements and best practices guiding such analyses.Footnote 21

The scorecard method assumes that it is plausible to develop a list of specific questions addressing the content of a RIA and its compliance with predefined requirements. Then, such a questionnaire (or scorecard) is applied to scrutinise specific RIAs, question by question, by assigning them points.Footnote 22

The “scorecard” methodology had been evaluated by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) – the US RIA scrutiny body located within the Office of Management and Budget – to determine its suitability for the institutionalised oversight of RIA quality. The results of this evaluation indicate the main strengths and weaknesses of this scorecard method.

The OIRA report concluded that “for such a scorecard to be effective, the metrics should be both objective and meaningful, which is challenging. Objective metrics can measure whether an agency performed a particular type of analysis, but may not indicate how well the agency performed this analysis. In addition, the metrics may be too broad to reflect agency compliance with specific guidance on technical matters (e.g., how to conduct an underlying contingent valuation study that provides key information to a regulatory analysis).” Peer reviewers commenting on the OIRA report pointed out that the selection of scorecard items should reflect the “ultimate goal of encouraging agencies to improve regulatory impact analyses to aid decision-making”, rather than “creating a perfect RIA”.Footnote 23 Essentially, these comments spelt out concerns with the scorecard design and its application for the institutionalised oversight of RIA quality.Footnote 24

Indeed, over the years – as various scholars applied scorecards to examine RIA quality – the scope of the included questions widened. However, they could be broadly classified into what are called the “accessibility block”, the “diagnosis block”, the “expected impacts block” and the “implementation/evaluation block”. In line with this classification, the review of selected scorecards is summarised in Appendix 1.Footnote 25

In addition, the RIA coding procedure has evolved. For example, Ellig and McLaughlin proposed a “qualitative evaluation of how well the analysis was performed [on the 0–5 scale], rather than an objective ‘yes/no’ checklist of analytical issues and approaches covered”.Footnote 26 Although such an approach would fine-tune the quantitative analysis, it also raises concerns over the subjectivity and replicability of the results (to overcome these concerns, Ellig and McLaughlin proposed a specific evaluation protocol).

2. Designing a scorecard for anti-pandemic restriction regulatory impact assessments

To design a scorecard to evaluate the RIAs accompanying sixty-four executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions, the insights from the literature review were combined with (1) a Polish RIA templateFootnote 27 and (2) the specific context of the anti-pandemic policy development.

The proposed scorecard was organised into five blocks: “Consultations”; “Problem identification”; “Evidence base”; “Estimated impact of the imposed measures” and “Evaluation”.

A summary of “Consultations” is required by the Polish RIA template. This constitutes the mandatory stage in the typical law-making process, as defined in the Cabinet Bylaw,Footnote 28 although it can be skipped under the “urgent” procedure. Given the scope and depth of the implemented policy interventions (involving closures of whole economic sectors), one would expect a sound policy formulation process to involve some sort of consultation with stakeholders, although the urgency of the pandemic response might affect the mode of such consultations.Footnote 29

The second block of the proposed scorecard, “Problem identification”, refers to the very first box of the Polish RIA template: prominence in evidence-based policymaking. On the one hand, during the pandemic outbreak, this process was likely to be neglected, as “the problem” appeared to be quite obvious. Consequently, the issue of defining operational goals seemed to boil down to “saving lives”.Footnote 30 That seemed also to be the case for cost–benefit analysis and zero-option considerations. Although life valuation techniques are well-developedFootnote 31 and routinely practised in industrial regulation (say, transportation security), it is difficult to document their usage in COVID-19 pandemic management across the developed world. Just as Stanley Kubrick’s President Muffley rejected General “Buck” Turgidson suggesting “two admittedly regrettable, but ‘distinguishable’, postwar environments: one where you got twenty million people killed, and the other where you got a hundred and fifty million people killed”,Footnote 32 contemporary politicians largely refused to monetise pandemic deaths (or at least go public with that). Nevertheless, one would expect a sound policy formulation process to be based on some systematic collection and analysis of the data, which should be indicated in this section of the scorecard.

The third block of the proposed scorecard referred to the “Evidence base” supporting the introduced restrictions. This is consistent with the second box of the Polish RIA template. Given the “evidence-based policymaking” paradigm, this aspect is undoubtedly important but again problematic in the pandemic environment. First, running rigorous studies (eg randomised controlled trials) takes time, and the dynamics of a pandemic put pressure on taking quick and bold action. As was explained by Swedish epidemiologist-in-chief A. Tegnell: “It is difficult to talk about the scientific basis of a strategy with this type of disease because we do not know much about it and we are learning as we go. Lockdown, closing borders – nothing has a historical scientific basis, in my view.”Footnote 33 Such a context would favour the precautionary principle: it is better to err on the side of too severe than too lenient action. Second, even a year into the pandemic, the evidence base regarding the effectiveness of surgical masksFootnote 34 or other non-pharmaceutical interventionsFootnote 35 was not necessarily clear.

Keeping in mind these practical difficulties in pandemic policymaking, we proposed two categories of evidence base: (1) strong – referring directly to the scientific evidence favouring specific policies, such as studies of the virus transmission risks in different economic sectors that could inform restrictions and closures; and (2) weak –comparative analyses arguing in favour of specific tools that had already been implemented in other (presumably more advanced in terms of analytical and governance capacity) countries. As the Polish RIA template includes specific boxes on (1) “proposed tools of intervention” and (2) a summary of the “EU/OECD comparative analysis”, the coding of these items is fairly straightforward.

The fourth block of the proposed scorecard addressed the core of the “impact assessment” idea through the “Estimated impact of the imposed measures”. The Polish RIA template requires the presentation of: (1) the monetised public finance (state and local budget) impact over a ten-year horizon; (2) the private-sector impact – either monetised or descriptive;Footnote 36 and (3) the labour market impact.

Given the unprecedented scope and depth of the policy interventions (including closures of whole sectors of the economy such as shopping malls, beauty services, pubs and entertainment), this aspect seems particularly important. On the other hand, the very magnitude of the interventions makes sensible economic forecasting a daunting task. Nevertheless, one would expect a sound policy formulation process to deliver some data that, falling short of an explicit cost–benefit analysis, would inform decision-makers on the scale of expected side effects.

Finally, in line with the “evidence-based policymaking” paradigm, the Polish RIA template includes an evaluation box that is coded in the last block of the proposed scorecard. It is expected to provide quantitative metrics and relevant targets that will be applied to assess the effectiveness of the implemented policies. As such, it conceptually refers to the “Problem identification” box. Specifically, the goals of the policies should be stated and indicators facilitating their evaluation provided, thereby enabling the evaluation of whether the problem was solved or adjustments to the policy were required.

In the context of the anti-pandemic restrictions, one would expect a sound policy formulation process to at least specify ad hoc quantitative metrics appropriate to determining the success or failure of particular restrictions – and perhaps some ex ante decision decision rules to maintain or alleviate them (see the discussion in Section III of the attempt to link newly confirmed COVID-19 cases to the colour-coded restriction packages).

The constructed scorecard is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Scorecard applied to examine the regulatory impact assessments accompanying the executive acts introducing anti-pandemic restrictions.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

V. Results

In applying the proposed scorecard to the sixty-four executive acts regulating Poland’s COVID-19 restrictions, it turns out that almost all of the coded RIAs scored 0 (on a 0–2 scale) on all coded items. Therefore, the summary of findings will – by necessity – be qualitative. The exceptions will be discussed below, ordered by coded item.

First, as far as problem identification is concerned, vague descriptions dominate. The very first analysed act, issued by the Minister of Health and proclaiming an “epidemic risk condition” (Dz.U.2020.433), cites the “growing risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection” and already “identified COVID-19 cases”, and it observes that “prophylactic measures are necessary”. The very same phrase had been invoked in the RIA accompanying the Minister of Health act proclaiming the “epidemic condition” (Dz.U.2020.491). This phrase had been also used in the amendment of this act strengthening the restrictions (Dz.U.2020.522) – this time “further prophylactic measures” had been “necessarily” implemented (the linguistic habit of providing categorical conclusions – always in the passive voice – without referring to any evidence base is typical in the analysed RIAs).

Another major policy implemented by the Council of Ministers via executive act was the implementation of “red” and “yellow” zones (Dz.U.2020.1356) depending on the “higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection”, and this was not accompanied by any reference to the quantitative indicators of this risk (in light of the public communication reviewed in Section III, it seems that “risk of infection” had been measured by the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases per 100,000 inhabitants; however, this fact – and the rationale behind selecting this particular metric – is not discussed in the RIA). As zones were updated, one amendment’s RIA (Dz.U.2020.1425) finally explicitly cited this metricFootnote 37 – and this was repeated in seven successive RIAs.

Another RIA (Dz.U.2020.1972) cited “data indicating that social mobility substantially increased”, but failed even to describe the sort of data being referred to (perhaps these were Community Mobility Reports provided by Google). In yet another RIA (Dz.U.2020.2353), one can read that the “analysis of the specific sectors of state activities and the economy, carried out by respective ministries, proved the necessity of” doing exactly what was done through this legal act – without any further elaboration of the original RIA document.

In line with the coding protocol devised in the previous section, all of these examples had been assigned a score of 0, as they failed to accurately refer to any evidence base or even data sources.

The first RIA that scored 1 on the 0–2 scale modified the “red” and “yellow” zones (Dz.U.2021.436) and explicitly referred to the “number of inhabitants infected with SARS-CoV-2 per 100 000” (this metric was also cited in a subsequent amendment, Dz.U.2021.446). The same act regulated that people who had recovered from COVID-19 could be vaccinated after three months with a single vaccine dose, citing “clinical reasons”.

The only RIA that scored 2 on the 0–2 scale on problem identification (Dz.U.2021.512) introduced the metrics upon which restriction decisions would be based, specifically (1) the average daily number of cases per 100,000 inhabitants, (2) the share of (public) hospital beds occupied and (3) the share of critical care beds (ventilators) occupied in public hospitals. The regulation had been issued on 19 March 2021 amid a declining number of new COVID-19 cases (the previous indicator), which was interpreted as justifying lifting the restrictions.

Second, as far as best practices are concerned, just four of the examined RIAs provide actionable comparative analyses. The first three referred to soccer games in the UK, Germany, Spain and Czechia (Dz.U.2020.750, Dz.U.2020.820 and Dz.U.2020.878, with the third one also cited lifting the border quarantine for Baltic states). The fourth (Dz.U.2020.904) – scoring 2 on the 0–2 scale – discussed travel restrictions in Sweden, Czechia and South Korea – no in-depth explanation was provided for the selection of these particular cases (although Sweden seems to offer the best-known European example of light-touch pandemic management, whereas South Korea had been widely praised for its application of a contact-tracking system to combat the pandemic).

Third, as far as the public finance impact is concerned (traditionally one of the strongest points of Polish RIAsFootnote 38 ), the analysed RIAs were poorly informative. The first of them – introducing the “epidemic risk condition” (Dz.U.2020.433) – proclaimed that it is impossible to estimate the “potential impact” on the “central budget”. That phrase was repeated in three subsequent RIAs (Dz.U.2020.491, Dz.U.2020.522 and Dz.U.2020.531). In the case of another four RIAs, estimates of the fiscal impact were discussed explicitly, and they scored 1 on the 0–2 scale. They dealt with rehabilitation holidays for servicemen and veterans (Dz.U.2020.1161), anti-stress holidays for civilians (Dz.U.2020.1356), COVID-19 testing in care homes (Dz.U.2020.1505) and rehabilitation holidays for disabled people and their custodians (Dz.U.2020.1758).

Fourth, the examined RIAs neglected to discuss private-sector impacts, even in descriptive terms (as opposed to efforts to monetise these impacts to facilitate cost–benefit analyses). Only two of them provided any specific information: first, on the costs of introducing mandatory temperature measurements for aeroplane passengers and of sanitising aeroplanes (unit cost of PLN 3000); and second, proclaiming (without reference) that allowing aqua-parks to operate at 50% capacity would allow them to reach a break-even point (therefore no longer generating loses).

Fifth, as far as monetisation of the private-sector impact is concerned, only one RIA (Dz.U.2020.792) scored positively, as it provided a monetary assessment of the Ekstraklasa soccer team revenues lost in the case of (1) maintaining game bans (PLN 192 million) and (2) a proposed lifting of some restrictions (limiting revenues lost to PLN 65 million).

Sixth, the labour market impact – one of the most important side effects of the lockdown-based pandemic management strategy – was neglected in the analysed RIAs. In the case of imposing restrictions, the RIAs proclaimed that the proposed regulations “will have” or “could have” an impact on the labour market (particularly for the services in which restrictions would be imposed). Two RIAs proclaimed a positive impact on the labour market as far as the sports sector is concerned (Dz.U.2020.792 and Dz.U.2020.820); these are the same RIAs as those that discussed best practices in returning to soccer games being held.

Finally, not a single one of the examined RIAs provided any guidance regarding the evaluation process, let alone indicators that should be applied to examine the effectiveness of the adopted restrictions or decision rules (milestones, holistic criteria) regarding lifting/imposing these restrictions or rules in the future.

VI. Conclusions

The reported qualitative results – and, above all, the fact that the application of the proposed scorecard to the sixty-four executive acts failed to deliver any meaningful quantitative results (as virtually all of them scored 0 on all items) – provides strong support for the conclusion that the RIA process of these acts failed to support the policymaking process with sort of evidence base as envisioned when compulsory RIAs had been introduced.

The documents were shallow, not only failing to provide a sound evidence base for the specific anti-pandemic measures (indeed, a demanding threshold during the “learning by doing” in the first year of the pandemic) or estimates of their economic impacts (a daunting task for economic modellers and forecasters due to the unprecedented character of the introduced lockdown measures), but even failing to provide comparative data on the restrictions introduced in other EU/OECD countries. Moreover, we must stress the lack of any evaluation information in these documents (guiding either the effectiveness of the introduced measures or providing a roadmap for introducing new ones). In addition, the lack of consultations and the rapid pace of draft development highlight the extraordinary hurry that this process involved and the neglect of the interests and knowledge available to non-cabinet actors.

Overall, the collected data demonstrate that the law-making process – and its “evidence-based policymaking” tools such as the RIAs and public consultations – provided to be mere window-dressing.

This observation could be interpreted in two (not necessarily mutually exclusive) ways.

First, one could hypothesise that the ad hoc pandemic management process crowded out the law-making process with tools such as RIAs and consultations. In other words, the genuine decision-making occurred elsewhere (with the exact process being largely invisible to public opinion and scholars, but plausibly fulfilling the requirements of rationality and evidence-based decision-making), and drafting legal texts simply codified decisions that had already been made, perhaps with in-depth consideration of the input from the Medical Council. Notably, beyond the timespan covered in this article, in mid-January 2022, “13 of the 17 members of the COVID-19 Medical Council explained their reasons for leaving the body. Complaining of a lack of cooperation from the government, … [they also] criticised ‘the discrepancy between scientific and medical reasoning and practice’ in the government’s approach to past and current waves of infection.”Footnote 39

Second, an admittedly more pessimistic interpretation suggests that the process simply had not been evidence-based, perhaps due to the scale of uncertainties and the pressure of time and the stakes involved. As a consequence, ad hoc politics and uncoordinated ideas from various centres of power (including specific cabinet ministers) could dominate sound decision-making. In this context, one could refer to the quixotic response of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister to the freedom of information request of the non-governmental organisation Citizen Network regarding the background of the surprising decision to close cemeteriesFootnote 40 before All Saints Day in 2020 – a holiday that is traditionally widely celebrated in Poland. The official denial included the following explanation:

I hereby inform, you that the reconstruction of the thought processes associated with this particular decision of the Prime Minister – and identification, whose advice had been helpful of crucial in making this decision – is practically impossible … It occurred over one year ago, and tracing back the path to the abovementioned decision in a precise manner is impossible even for the decision-maker himself. The consultations lacked formal character and minutes had not been prepared.Footnote 41

Unfortunately, given the lack of reliable and publicly accessible evidence, as well as the level of political polarisation and the erosion of democratic practice that can be observed in contemporary Poland, the differentiation between these two alternatives would require some sort of official inquiry – following the example of UK’s House of Commons, Science and Technology Committee and Health and Social Care Committee report entitled “Coronavirus: Lessons Learned to Date”, which examined the initial UK response to the pandemic.Footnote 42

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2022.18.

Financial support

This research has been supported by the Polish National Science Centre Grant no: 2016/23/B/HS5/03542.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.