Introduction

Political support for non-mainstream parties has risen against the backdrop of the 2008 Great Recession. In the wake of the economic crisis, recent elections in some European countries have often resulted in important gains for new and challenger parties (Hino, Reference Hino2012; Hobolt and Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016). Following an economic voting logic, dissatisfied voters initially punished incumbents for their failing economic performance, voting for the mainstream opposition (Bartels, Reference Bartels2014; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014; Magalhães, Reference Magalhães2014); yet, the continuity of the crisis and the implementation of austerity policies by all of the mainstream parties have finally driven many discontented voters to support new and challenger parties (Kriesi and Pappas, Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015; Hobolt and Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016).

Besides voters’ political and economic disaffection, this article proposes an additional mechanism to account for the rise of new parties, namely voters’ attitudes toward democratic decision-making processes. New and challenger parties stand not only as fierce critics of the incumbents’ economic management, but also as political reformers of democratic procedures. In doing so, they might have matched the supposedly growing demand for changes in political decision-making among western publics.

However, little is known about the effect of the public’s attitudes toward different procedures of decision-making on voting behavior. This article fills this gap by analyzing, for the first time, how stealth democracy attitudes, as defined by the seminal study of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), affect individuals’ support for some new and challenger parties that have risen in the context of the 2008 Great Recession.

Stealth democracy attitudes gather together preferences on democratic political decision-making procedures, leaning not toward individuals’ increase in political engagement, but in favor of delegation, efficiency, and experts’ involvement in political decision-making. Stealth democracy attitudes also are reactions against ‘politics as usual’, and following the 2008 Great Recession they have increasingly captured scholars’ attention (Bengtsson and Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2012, Reference Font, Navarro, Wojscieszak and Alarcón2015; Webb, Reference Webb2013; Coffé and Michels, Reference Coffé and Michels2014), but an analysis of their potential electoral consequences is still lacking.

Using data from a 2015 survey, we analyze the recent and far-reaching transformation of the Spanish party system, where two new parties, Podemos (We Can, on the radical-left), and Ciudadanos (Citizens, on the center-right), entered the parliamentary arena. The Spanish case allows us to explore how stealth democracy attitudes affect the support for new and mainstream parties differently [in our case the Socialist Party (PSOE) and the Popular Party (PP)], but also how they influence in dissimilar ways the support for new and challenger parties of different ideological inclinations. In this regard, although both Podemos and Ciudadanos are new parties (entering the national parliament for the first time in 2015), and present themselves as political reformers in clear contrast to the mainstream parties, Podemos is a radical-left pro-participatory democracy party corresponding to the definition of challenger party (as proposed by Hobolt and Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016: 3–4),Footnote 1 while Ciudadanos is a centrist one aiming for much more moderate political reforms. Their presence increases the diversity in what Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 59) call the ‘process space’ of competition, presenting different party views on the democratic decision-making processes and putting them high on the agenda. In this way, voters dissatisfied with the political process have an alternative to mainstream parties and, following Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), stealth democracy attitudes should influence party choice in such a context. Consequently, the Spanish setting is an optimum circumstance to test the effect of stealth democracy attitudes on party support.

Our findings show that the stealth democracy index (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) helps to predict the intention to vote for new and challenger parties: negatively for the radical-left Podemos, and positively for the center-right Ciudadanos. These findings support Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) insights because Podemos is a populist and pro-participatory democracy party, while Ciudadanos aims to reform democratic procedures without calling for high-intensity citizen participation. We show that the electoral impact of these attitudes is independent from structural factors as well as the influence of other short-term orientations. Additionally, we find evidence of this relationship being conditional on voters’ ideology. Stealth democracy attitudes increase the probability of voting for the new center-right Ciudadanos when voters are ideologically moderate. Therefore, stealth democracy attitudes are not only important because they are widely spread, but also because they play a relevant role in explaining voters’ preferences for a new type of right-to-the-center party.

This study makes a series of valuable contributions. First, it updates the information about stealth democracy orientations with data from a period in which the consequences of the public’s discontent after the 2008 Great Recession in Western Europe are fully apparent in the attitudes toward decision-making processes. It replicates Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s model for Spain confirming that stealth democracy orientations are widely spread and that the numbers of those in favor of experts’ involvement in policy-making have increased.

Second, this article extends the field of study of stealth democracy attitudes. Although previous studies have investigated the determinants of these attitudes, they have left the electoral consequences of stealth democracy unexplored. This article explores the effects of these attitudes on party choice. In doing so, it increases our knowledge on the attitudinal determinants of the rising support for new and challenger parties.

Third, our results also inform the debate about the ongoing party systems change in Western European countries. While much information is already available on the determinants of the radical-right populist vote, our analyses demonstrate how, in the present context of political disaffection, stealth democracy attitudes foster the support for right-to-the-center parties that, although critical of ‘politics as usual’, cannot be considered radical populists. Therefore, we illustrate how an unexplored attitudinal dimension contributes to party system change in the context of economic and political discontent.

Finally, this article contributes to the methodological discussion about the suitability of the stealth democracy index (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) examining the effect of its different components separately. With this exploratory exercise, the study provides a more nuanced image of the relationship between stealth democracy and voting: we find that support for experts’ involvement in decision-making is critical when explaining the vote for the new center-right party Ciudadanos.

The article proceeds as follows: the next two sections summarize previous findings in this field and present the hypotheses that guide our research, then we briefly introduce the Spanish context. After succinctly describing the data, the variables and the methods used in the analyses, we explain our main findings presenting an analysis of how stealth democracy attitudes affect the support for different parties, with a particular focus on the conditional role played by ideology. We end the article with a review of the limits of the stealth democracy index and an analysis that breaks down this conventional measure, and finally the conclusions and implications for further research.

Attitudes toward democratic decision-making processes and stealth democracy orientations

Political dissatisfaction and distrust for fundamental actors of representative democracies – such as parties and politicians – are widely spread in advanced democracies (Norris, Reference Norris1999; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Allen and Birch, Reference Allen and Birch2014). Demands for more participatory and direct decision-making processes have increased and have already been documented in some studies (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Bürklin and Drumm2001; Donovan and Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2006; Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Bengtsson and Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Anderson and Goodyear-Grant, Reference Anderson and Goodyear-Grant2010; Neblo et al., Reference Neblo, Esterling, Kennedy, Lazer and Sokhey2010). However, the literature has also shown some limits in the support for increased participation (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Bürklin and Drumm2001; Donovan and Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2006; Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2012), has demonstrated that these demands do not translate into actual participation (Webb, Reference Webb2013), and has cast doubt on the nature of the support for more direct procedures (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970; Barber, Reference Barber1984).

The influential studies of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2001, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) probably portray the most skeptical views of both the advantages of participatory democracy and of the commitment to this form of democratic participation in the United States. They argue that Americans prefer a stealth version of democracy, one in which the usual representative democracy institutions and procedures are in place and work better, and which does not require much involvement from and monitoring of the citizens. Stealth democrats would not be very interested in the high-intensity commitment implied by participatory or deliberative political processes, favoring instead delegation, efficiency, and expert input in the decision-making processes. As Hibbing and Theiss-Morse say, stealth democrats’ preference is ‘for decisions to be made efficiently, objectively, and without commotion and disagreement’ (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 143). Stealth democrats prefer the involvement of experts and independent bodies in government decisions, and less partisanship, discussion, and individuals’ active political engagement. Thus, stealth democracy, with its negative view of debate and compromise, and its willingness to hand over decision-making to unaccountable but efficient actors, would be opposed to the deliberative or participatory versions of democracy and would entail even less citizen involvement than the standard representative democracy (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 2, 10, 161, 239).

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) and other studies that have followed their thread have analyzed the political correlates of stealth democracy attitudes. Font et al. (Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2012) found for the Spanish case that right-wing ideology is associated with stealth democracy attitudes. Webb (Reference Webb2013) analyzed the political attitudes associated with stealth democracy orientations for the British case confirming that stealth democrats tend then to avoid increased political commitment. Additionally, Webb (Reference Webb2013) found that they express distinguishing views regarding decision-making processes and political participation, being less eager to be involved in conventional (party and non-party arenas) and deliberative types of participation than in the referendum democracy type of participation.Footnote 2

However, our knowledge about the relationship between stealth democracy orientations and political preferences is limited. Among the gaps in our knowledge are the effects of stealth democracy attitudes on party support. Apart from the Democrats’ aversion to stealth democracy reported by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002), there is very little research on the impact of these attitudes on party preference. However, as Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) suggest, these orientations may, under specific circumstances, influence party choice. As they rightly discuss (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 72–74), attitudes toward decision-making processes should not be expected to have a great impact on party preferences when all parties share similar policies regarding political procedures. However, if voters are dissatisfied by the decision-making process and there is a party that makes reforming those political processes a relevant element in its agenda, voters may feel attracted to such a party. This is what, following Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 74), occurred in the United States with the support for the third-party candidate Ross Perot in 1992 and 1996.

Stealth democracy and party politics

Those circumstances in which attitudes toward decision-making processes, such as the stealth democracy orientations, may affect party preference are prominent in Western Europe. Parties have reacted to this challenging environment, which, outstandingly, includes a rise in citizens’ mistrust for conventional political actors (Dennis and Owen, Reference Dennis and Owen2001; Mair, Reference Mair2013). There has been a growth in the use of referenda, deliberative mechanisms, and other participatory devices across advanced democracies (Smith, Reference Smith2009; Michels, Reference Michels2011). Moreover, in organizational terms, numerous parties have adopted more inclusive internal procedures (Cain et al., Reference Cain, Dalton and Scarrow2004). However, despite these efforts, new, challenger, and populist parties make strategic use of citizens’ discontent toward their mainstream competitors (Bergh, Reference Bergh2004; Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2014; Passarelli and Tuorto, Reference Passarelli and Tuorto2016). Many of these parties present themselves to the public as anti-political-establishment parties, criticizing the privileges of mainstream parties and ‘politics as usual’. In different ways, these parties propose weakening the political-establishment grip on decision-making; some propose reducing the role of parties in decision-making processes, favoring anti-majoritarian institutions or non-party political procedures; others propose the use of participatory and direct democracy decision-making processes to strengthen common citizens’ political influence (see e.g., Bordignon and Ceccarini, Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2013). Therefore, in some European party systems there are notable differences between mainstream and non-mainstream parties in the ‘process space’ of competition suggested by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 59). This could cause process disaffected voters to support parties that oppose the mainstream ones and put high political reform on the agenda.

Consequently, in some western societies, the public’s stealth democracy orientations that, as Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) argue and Font et al. (Reference Font, Navarro, Wojscieszak and Alarcón2015) highlight, express a discontent with ‘politics as usual’, might have been matched by some parties that appeal to voters, presenting themselves as anti-mainstream political reformers. However, this critical connection between stealth democracy attitudes and party choice has not been empirically tested in Europe yet. This is our contribution. Particularly, in countries experiencing economic and political crises, such as the ones that have been suffered by Spain and many other European nations since 2008, stealth democracy attitudes might foster support for these parties. If that were the case, it would have important implications for our understanding of recent party system changes in Europe.

We expect, then, stealth democracy attitudes to increase the likelihood of support for new and challenger parties’ criticisms of the mainstream and ‘politics as usual’, but also to be adverse to participatory transformation of the democratic system. For the Spanish case, as we describe below, the new right-wing party, Ciudadanos, proposes political process reforms but it does not aim for high-intensity citizen involvement (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodrígez-Teruel and Barrio2016); thus we expect stealth democracy orientations to positively affect the intention to vote for this party (Hypothesis 1).

Additionally, given that stealth democrats have been found in previous studies to be less likely to be left-wing and not inclined toward high-intensity political involvement, we do not expect stealth democracy orientations to increase the likelihood of supporting the new radical-left populist party, Podemos, despite this party being anti-mainstream. Podemos has intensely proposed direct democratic reforms and, in contrast to Ciudadanos, it has expressed its support for more participatory and deliberative mechanisms of decision-making.Footnote 3 Therefore, we expect a negative relationship between stealth democracy orientations and support for Podemos (Hypothesis 2).

Finally, following the same perspective, we expect stealth democracy orientations to decrease the support for the mainstream parties because they are part of the political establishment and ‘politics as usual’, against which individuals of stealth democracy orientations react (Hypothesis 3).

The Spanish case: new parties and political discontent

Spain is an interesting case for testing the effect of stealth democracy attitudes on party preferences. The Spanish context matches very well the circumstances in which, according to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) suggestion, stealth orientations should matter. As we describe in the next paragraphs, there is an intense dissatisfaction with mainstream politics and new parties offering an agenda of political reform. For a long time, considerable political disaffection has certainly characterized Spanish public opinion (Montero et al., Reference Montero, Gunther and Torcal1997), but the discontent has been strengthened because of and during the Great Recession (Orriols and Rico, Reference Orriols and Cordero2014). Amidst an intense dissatisfaction with the country’s economic situation, the evaluation of the political situation has reached very negative levels, and parties and politicians are considered among the major problems of the country (Torcal, Reference Torcal2014a).Footnote 4

Additionally, polls and elections results during the crisis signaled a situation of partisan dealignment, with the two largest mainstream parties, the center-left PSOE and the conservative PP, losing support since the worsening of the economic indicators (Torcal, Reference Torcal2014b; Cordero and Montero, Reference Cordero and Montero2015). Spanish public opinion has rejected both the incumbent and the mainstream opposition parties, irrespective of whether it was the PSOE or the PP in office. The then incumbent PSOE was first held responsible for the bad economic results between 2008 and 2011, but the PP very soon suffered from voters’ dissatisfaction after entering office in 2011. However, the public did not reconcile with the PSOE after it lost office or while it was in opposition in the 2011–15 period. Thus, both the mainstream incumbent and opposition parties have suffered from public dissatisfaction.Footnote 5 Besides that, soon after the implementation of the first packages of austerity policies, a widely spread mobilization arose in the spring of 2011: the 15-M or indignados movement. The indignados argued that political elites and mainstream parties were not representing ‘the people’. One of their main demands was a thorough political reform granting a greater role to individual citizens in the decision-making process (Font et al., Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2012).

The Spanish party system underwent an important transformation in the 2014 European Parliament elections, the 2015 local and regional elections (Rodon and Hierro, Reference Rodon and Hierro2016) and, finally, in the 2015 (Orriols and Cordero, Reference Orriols and Rico2016) and 2016 general elections. The two main beneficiaries of the economic and political crisis have been two new nation-wide parties: Podemos and Ciudadanos. They are both harsh critics of the mainstream PP and PSOE, present themselves as tough detractors of the political corruption that has affected the PP and, to a lesser degree, PSOE governments, and defend the ‘democratization’ of parties’ internal procedures, favoring primaries to select party candidates.

Ciudadanos is a new center-right or liberal party that has very often stressed its nature of political reform, proposing a catalogue of policies aiming to revitalize Spanish democracy (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodrígez-Teruel and Barrio2016). They defend a reduction of party influence on the judiciary and public prosecution systems, and of MPs and politicians privileges, leaner public administration, a strengthening of the control functions of parliament, and an increase in transparency and access to government information (Ciudadanos, 2015). However, in its 2015 manifesto, policies aiming to enhance citizens’ participation were circumscribed to the local government level and to the simplification of the popular legislative initiatives procedures.

Podemos is a new radical-left party that uses populist discourse (Llamazares and Gómez-Reino, Reference Llamazares and Gómez-Reino2015; Ramiro and Gomez, Reference Ramiro and Gomez2017). Having been formed by a group of left-wing activists, Podemos’ platform includes both anti-political-establishment claims and participatory demands. The populist leaning of the party is reflected in its use of the people vs. elite dichotomy. Consequently, Podemos has targeted in its attacks the political-establishment and mainstream parties, identified as ‘caste’ parties. While in some political reform policies Podemos does not differ from Ciudadanos, the former is much more ambitious and radical in its participatory plans. Podemos defends deliberative democracy, recall referenda, mandatory primaries, and citizens’ involvement in policy evaluation (Podemos, 2015).

In sum, Spain displays high levels of dissatisfaction with key representative democracy actors such as parties, while new parties (Ciudadanos and Podemos) offer alternative policies aiming to reform the political process. Stealth democracy orientations should foster the support for these parties as Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) suggested. However, they differ in their manifestoes’ content regarding the desired level of citizens’ involvement in political decision-making. It is these differences regarding decision-making processes that divert our expectations of the effect of stealth democracy attitudes on party choice (Hypotheses 1 and 2 above).

Data and methods

Questions on preferences about political decision-making processes are rarely asked in regular surveys. To test our hypotheses and overcome the lack of suitable data we included 11 questions about this topic in a telephone survey (n=1200) conducted in Spain in 2015.Footnote 6

Our measure of attitudes about stealth democracy is the index developed by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) built upon respondents’ agreement with these statements:

1. It would be better for the country if politicians stopped talking and took action on important issues.

2. In politics, compromise is really selling out one’s principles.

3. Politics would work better if political decisions were left up to successful business leaders.

4. Politics would work better if political decisions were left up to experts instead of politicians or citizens.

Favorable responses (strongly agree/agree) are interpreted as supportive attitudes toward stealth democracy. The index is an additive scale going from 0 to 3 where a positive response to each of the first two questions, and to at least one of the last two, scores 1 point. Thus, those scoring 0 in the stealth democracy index disagree with all statements, while those scoring 3 express some level of agreement with the first and second statement as well as with one of the third and fourth assertions. Table 1 shows frequencies for the level of agreement/disagreement with the four separate items in the index (Panel A), and the distribution of the stealth democracy index (Panel B).

Table 1 Measuring stealth democracy

October 2015 Barometer survey, Metroscopia.

Almost all respondents (95%) agree with the ‘less talk and more action’ statement, while the number halves when it comes to whether or not compromising should be taken as abandoning principles. Only one out of three sympathizes with the idea that leaving decisions to successful business people would make politics work well, and three out of four support leaving decisions up to experts instead of politicians or citizens. After computing the Hibbing and Theiss-Morse stealth democracy index we learn that 52% of the respondents score 3 points (the maximum), while 35% score 2 points, 11% only 1 point, and a very marginal fraction of the sample none. Therefore, there is extensive support for stealth attitudes among Spaniards.

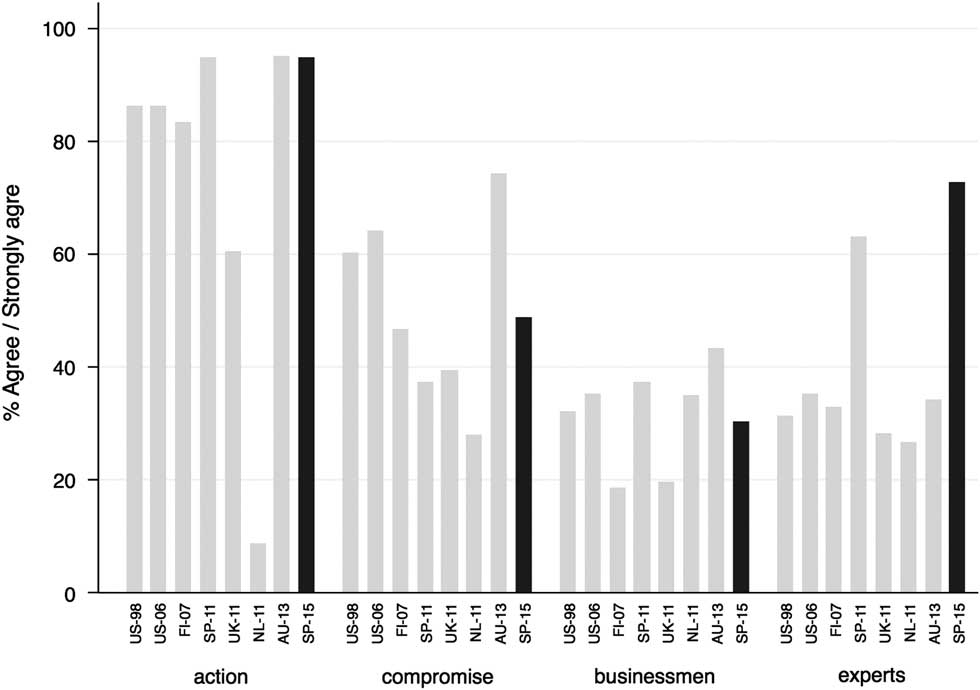

These results are not far from what has been found in other advanced democracies.Footnote 7 A cross-country comparative check confirms this picture, but with some nuances and limits to the comparison.Footnote 8 Figure 1 shows frequencies of positive responses to the four questions employed to build the index as reported in several studies for different countries. Spaniards are indeed among the most convinced about the need for more efficient politicians (talk vs. action), though Australians display the same level of agreement (95%), while in the United States (both in 1998 and 2006) and Finland there are also high levels of support for this opinion (>80%).Footnote 9 Evaluations of ‘compromise’ in politics are very similar to those reported in the United Kingdom and Finland (around 40%), but the percentage who respond positively to the idea of compromise as abandoning one’s principles has increased by 10 points over the last 4 years in Spain, yet it is still behind the United States and Australia levels (>60%).

Figure 1 Stealth democracy orientations: a cross-national view.

Regarding Spaniards’ willingness to delegate political decisions to non-political actors, support for turning responsibilities over to successful businessmen has decreased from 37% in 2011 to 30% in 2015. Still, it is around the same level as the United States, the Netherlands, and Australia. Yet, what it is particularly noticeable in the Spanish surveys is the high percentage of respondents agreeing with the idea of turning political decisions over to independent experts (instead of politicians or citizens): 62% in 2011 and 72% in 2015 (the support registered in other countries is always around 30% and it never goes beyond 35%).

In our vote models, the dependent variable is party support, that is, individuals’ intention to vote for a party. Aside from the stealth democracy index, we include the standard socio-economic and demographic controls in voting models: a continuous variable for age (Age); a dichotomous variable for sex, female being the reference category (Sex); a four-category variable of subjective social class introduced as dummy variables with ‘lower-class’ as the reference category (Lower-middle class, Middle class, Upper-middle class, and Upper class); a dichotomous variable for employment status (Unemployed); an ordinal variable for the respondent’s level of education (Education);Footnote 10 and a variable capturing the interviewee’s self-placement in the left-right ideological scale, 0 being extreme left and 10 extreme right (Ideology).

In order to obtain an unbiased coefficient for stealth democracy, we run the models also accounting for a set of attitudinal variables that might confound with stealth democracy orientations, namely, a 0–10 range continuous variable for the level of dissatisfaction with democracy (Dissatisfaction with democracy), and another three 0–10 range continuous variables measuring the support for different types of political decision-making processes (Referendum; Deliberative participation; Electoral participation). Finally, we estimate a last model adding a five-category variable capturing the interviewees’ evaluation of the current economic situation (Evaluation of the economy).

Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in the Online Appendix. We do logistic regression analyses since our dependent variable is a dichotomous variable coding individuals’ intention to vote for a party, although results are robust to ordinary least squares (OLS) estimations.

Stealth democracy orientations and their effect on party support

The analysis of the influence of stealth democracy orientation on party choice using the Hibbing and Theiss-Morse index confirms two of our hypotheses (Table 2).Footnote 11 A marginal increase in the stealth democracy index boosts the likelihood of voting for the new center-right political-reform party Ciudadanos (Hypothesis 1), while it decreases the likelihood of supporting the radical-left populist Podemos (Hypothesis 2). However, the latter association is not as statistically strong as the former. In contrast, the stealth democracy index is not a significant predictor of the support for mainstream parties and Hypothesis 3 should not be accepted.

Table 2 Electoral support for mainstream and new and challenger parties

PSOE=Socialist Party; PP=Popular Party; VIF=Variance Inflation Factor.

Logistic regression results.

Standard errors in parentheses; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

As we expected, the findings shown in the last three columns of Table 2 point out how stealth democracy orientations, with their indifference toward citizens’ involvement, are associated with support for Ciudadanos. Ciudadanos’s rise can be conceived then as the product of public dissatisfaction with ‘politics as usual’ as performed by mainstream parties during the recession. Matching this party’s moderate position regarding citizens’ involvement in decision-making, Ciudadanos supporters do not seem very inclined toward individual high-intensity involvement. This finding holds after controlling for conventional factors in voting models (Model 1), attitudinal variables such as dissatisfaction with democracy and preferences for political decision-making processes (Model 2), or evaluation of the current state of the economy (Model 3). Moreover, this result is robust to additional checks regarding the way we estimate our coefficients, the specification of the model or the operationalization of the dependent variable.Footnote 12

The opposite relation was expected regarding the radical-left Podemos, and the analysis confirms our intuition. Besides being an anti-political-establishment party, Podemos strongly defends participatory democracy and deliberative procedures that contrast with the reservations about high-intensity political participation associated with stealth democracy. The effect of the stealth democracy index on the probability of voting for Podemos does not reach the conventional statistical level of confidence to validate our hypothesis (P-value=0.065). However, it does if coefficients are estimated with OLS (see O.A.1) or through a multinomial logistic regression where the probability of voting for Podemos is compared with the probability of voting for Ciudadanos (see O.A.6). In other words, we can take stealth democracy attitudes as a trustworthy (negative) predictor of voting if we focus on the competition between the new parties.

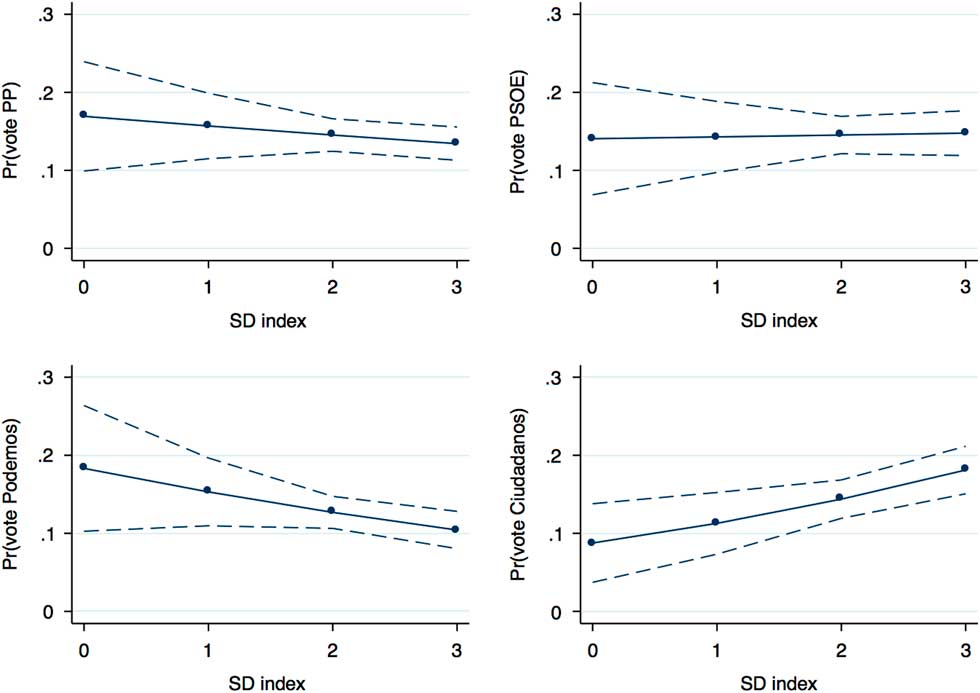

However, the stealth democracy index does not appear as a significant predictor in any of the models for mainstream party support (PP and PSOE). Figure 2 shows how the predicted probabilities of voting for each of the parties change across different values of the stealth democracy index. An increase in the strength of stealth democracy orientations increases the likelihood of supporting Ciudadanos and decreases it for Podemos, while the effects for PP and PSOE are indistinguishable across different values of the index.Footnote 13 In this way, the suggestion by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) of the opposed effects of stealth democracy orientations on party choice, negative for mainstream parties and positive for non-mainstream political-reform parties, only sees partial confirmation. In the case analyzed, only the latter effect is confirmed. Additionally, as we have shown, not all non-mainstream parties benefit from stealth democracy attitudes and their effect seems dependent on the non-mainstream party’s ideology and emphasis on citizens’ political involvement.

Figure 2 Predicted probabilities of party choice by stealth democracy attitudes.

Ideology is, in any case, a relevant variable to explain the electoral support for all political parties across the board and it has been shown in previous studies that stealth democrats have right-wing leanings. However, these two variables are not so highly correlated to make us think of a spurious relationship between stealth attitudes and party choices (correlation coefficient of about 0.12). We have assessed how ideological orientations condition the way stealth democracy attitudes affect party choice, thus deepening our understanding of how voters’ attitudes translate into voting preferences for some new parties. Table A.2 in the Online Appendix shows the results of the logistic models where the stealth democracy index is interacted with ideology (Model 1) and ideology squared (Model 2).Footnote 14 From these analyses we gain some more insights. First, voters’ ideology does not condition the null result about the effect of stealth democracy on the support for mainstream parties. Neither PP nor PSOE have an ideological space where having preferences against ‘political as usual’ pays off.

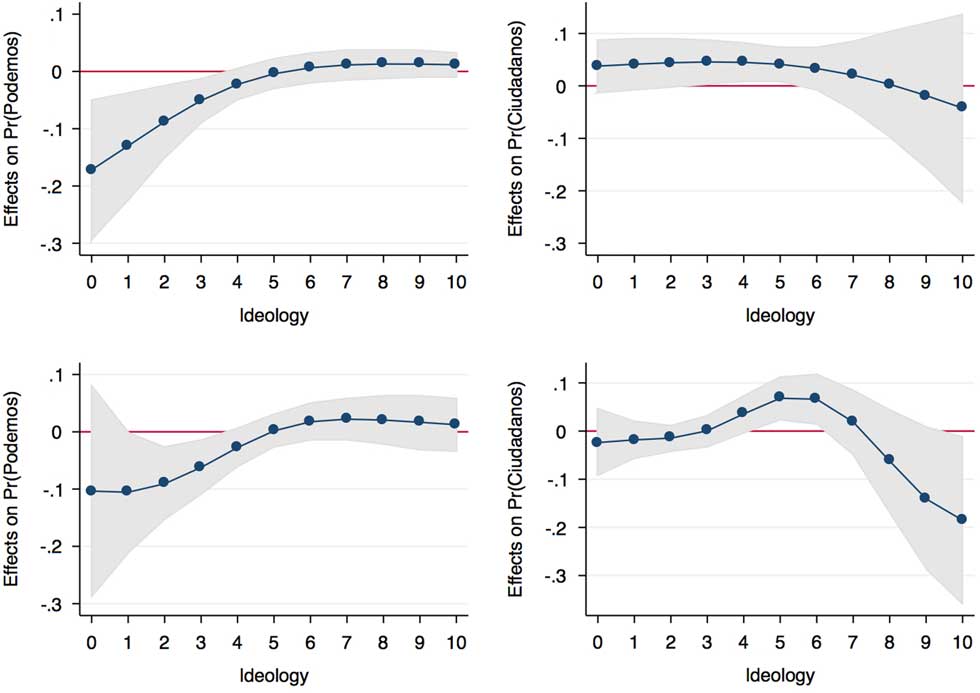

Second, the impact of stealth democracy attitudes on the probabilities of voting for new and challenger parties does vary across different levels of the ideological scale. However, the form in which ideology conditions such a relationship differs by party choice. Results from the interaction models for Podemos and Ciudadanos are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Stealth Democracy effect on the probability to vote for Podemos or Ciudadanos by ideology (upper row) and ideology squared (lower row).

On the one hand, the interaction between stealth democracy and ideology is negative and statistically different from zero in the analysis for Podemos. As expected, the range where the ideology moderates the relationship is in the left, namely between 0 and 3 (see the upper-left graph in Figure 3). As the ideological position of the interviewees moves to the right the marginal impact of stealth democracy on the probability of voting for Podemos decreases. Contrary to the unconditional analysis, this result gives support for Hypothesis 2: stealth democracy orientations are negatively associated with electoral support for the new radical-left populist party Podemos despite being anti-mainstream.

On the other hand, the linear interaction between ideology and the index of stealth democracy does not provide clear results on the probability of voting for Ciudadanos (upper-right graph in Figure 3). Yet, the non-linear interaction does (see bottom-right graph). Thus, stealth democracy attitudes especially contribute to the explanation of the votes for new right-to-the-center parties if voters are not ideological extremists.Footnote 15

Among the control variables, some results merit some additional comments. For instance, we find that the parameter for level of disaffection with the democratic system is negatively associated with the support for traditional parties. The probability of voting for PP or PSOE decreases as the level of dissatisfaction with democracy increases, which is consistent with the motivation of this study, that is, political discontent against the backdrop of the Great Recession. However, disaffection with democracy is not associated with support for the new and challenger parties. Neither voting for Podemos nor for Ciudadanos shows a significant relationship with discontent. These results suggest that some level of alienation from the democratic system could be a necessary but not sufficient condition for new parties to gain electoral support. This is something that indeed underlines the statistically significant findings found for the role of stealth democracy attitudes.

The variable measuring economic disaffection (Perception of Spanish economy) only plays a role in voting for either the incumbent party (PP) or the left-wing new challenger party (Podemos): positively for the former (the better the perception of the economy, the higher the probability of supporting the incumbent) and negatively for the latter. Although we would also have expected a negative effect in the model of Ciudadanos, since the Great Recession is taken as a trigger for the support for new and challenger parties, we find no impact. This result may be due to the differential effects of the economic crisis on (and the diverging perception of it from) parties’ electorates.Footnote 16

Discussion and concluding remarks

Our analysis shows that stealth democracy attitudes foster the support for new and challenger parties, particularly when they are moderate and they defend reforms on the democratic decision-making processes characterized by low-intensity citizen participation. In the Spanish context this is the case for the new right-to-the-center party, Ciudadanos. On the contrary, stealth attitudes decrease the support for new and challenger parties that enhance citizens’ involvement in the democratic decision-making process, like Podemos.

The analysis developed in this article, although novel, would not be complete without echoing the methodological discussion of the limits of the stealth democracy index. The index has shown its usefulness for comparative analyses, but it has also been subject to criticism. Webb (Reference Webb2013: 754) argues that the index fails to capture one of the critical dimensions of stealth democracy, namely people’s attitude toward conflict or dispute, which is intrinsic to the political debate. Neblo et al. (Reference Neblo, Esterling, Kennedy, Lazer and Sokhey2010: 577–578) suggest that people expressing stealth democracy beliefs may have conditional attitudes toward the content of the items, which could lead to different interpretations of the index. Font et al. (Reference Font, Wojcieszak and Navarro2012: 27) disagree with the aggregation of what they consider conceptually unrelated aspects of citizens’ preferences. Additionally, in the same line, Font et al. (Reference Font, Navarro, Wojscieszak and Alarcón2015: 163) demonstrate that business-based governance does not perfectly match the other expert-based items.

As in other studies, the index built with our survey data is not exempt from potential weaknesses. In fact, the aggregation of the four items of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s stealth democracy index in our survey produces a low-reliability Cronbach’s α score (0.36), although it improves upon the one obtained in a previous analysis of the Spanish case.Footnote 17 Therefore, without detracting from the theoretical content of the stealth democracy concept, we believe that due to the weakness of the measurement tool, studies using this index should also complement the analyses with further exploration of the separate effects of its four components. In doing so, we may derive a nuanced image of the relationship between stealth democracy and party choice.

Results of this exploration are shown in Table 3. They reveal a more complex picture than the one obtained using the compound index. Two of the index’s items, namely the support for the claims that ‘Politicians should stop talking’ and ‘Compromise is selling out one’s principles’, do not have any effect on voting intentions.Footnote 18

Table 3 The effects of stealth democracy components on party choice

PSOE=Socialist Party; PP=Popular Party.

Logistic regression results.

Standard errors in parentheses; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

What is more, the expected differentiation between mainstream and new parties’ supporters appears more blurred when the effects of the components of the index are observed separately. The vote for the mainstream conservative PP is positively related to the support for involving ‘successful business people’ in decision-making. This component also affects the likelihood of supporting the left parties, but in this case, in line with what Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 148)found for those who identified with the US Democratic party, the sign is negative: supporting the involvement of business people in decision-making decreases the likelihood of supporting either the new radical-left challenger (Podemos) or the mainstream center-left (PSOE) (although this effect is barely significant). Finally, supporting the role of non-elected experts in political decisions is only relevant in explaining the support for the new center-right Ciudadanos, increasing the likelihood of voting for it. This last result exemplifies how this extra analysis of the component of the index might illuminate further lines of research. For instance, in the emerging literature about preferences for technocratic governments (Pastorella, Reference Pastorella2016; Bertsou and Pastorella, Reference Bertsou and Pastorella2017), the role played by new and challenger parties has been absent so far.

In sum, these results demonstrate the role played by stealth democracy orientations (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) in party support. The relationship between this set of attitudes and party preference had not been empirically assessed before and our findings allow for a better understanding of unexplored attitudinal factors affecting recent party system changes. Yet, our findings also show that the effect of stealth democracy orientations – leaning not toward individuals’ increased involvement, but in favor of delegation, efficiency, and experts’ roles in political decision-making – could be more nuanced if the stealth democracy index is decomposed. For the Spanish case, one of the items included in Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) index seems to exert a particular influence on voting for the new right-to-the-center party Ciudadanos: a preference for experts’ involvement in politics. In this way, the results suggest that the theoretical contribution of the stealth democracy concept can sometimes be complemented from outside the index, as originally proposed.

Additionally, while the literature has advanced on the determinants of the radical-right populist vote, our analyses inform us about how stealth democracy attitudes might foster the support for right-to-the-center political reform parties critical of the ‘politics as usual’, such as the Spanish Ciudadanos – or potentially other recent newcomers such as The New Austria and Liberal Forum (Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum), Action of Dissatisfied Citizens (Akce nespokojených občanů) in the Czech Republic, or Bright Future (Björt framtíð) in Iceland. Our study shows that in a context such as the one generated by the Great Recession, disaffection with the political process and the presence of parties offering political reforms do favor these new parties. If this citizens’ discontent becomes a stable feature of western public opinion it will also be a permanent source of support for non-mainstream parties oriented toward the reform of political decision-making processes.Footnote 19

Further research is needed into the way in which these attitudes have an effect on the support for political reform parties in other countries and the methods to better measure and assess their influence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and the three anonymous referees for advice, which greatly improved the quality of this study. The authors also wish to thank Metroscopia Estudios Sociales y de Opinión S.L. for giving us the opportunity to include some questions in its Barometer. The authors are also in debt with Laura Morales, Pablo Simón, and the participants of the Political Behavior Seminar at the Pompeu Frabra University for their useful comments. All errors remain the authors.

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000108