Introduction

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most recent of three deadly coronaviruses to emerge in humans in the past decade [Reference Fung and Liu1]. Globally, by January, 25, 2022, the World Health Organization received reports of 349,641,119 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 5,592,266 deaths since the onset of the outbreak in December 2019 [2,Reference Dong, Du and Gardner3]. Governments worldwide implemented public health COVID-19 attenuation policies that consist of social restrictions (including lockdown periods), which have proved efficacious in indenting COVID-19 related infection and death [Reference Haug, Geyrhofer, Londei, Dervic, Desvars-Larrive and Loreto4–Reference Islam, Sharp, Chowell, Shabnam, Kawachi and Lacey7].

However, these strategies and the disease itself have acted as a catalyst for multiple biopsychosocial adversities. We use the qualifier “biopsychosocial capture” to capture the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. These experiences include the biological exposure to the COVID-19 infection and the social and psychological experiences of the COVID-19 attenuation policies, which include lockdown, social distancing, loneliness, financial loss, unemployment [Reference Pinilla, Barber, Vallejo-Torres, Rodriguez-Mireles, Lopez-Valcarcel and Serra-Majem8], secondary health effects (e.g., weight gain) [Reference Weaver, Hunt, Armstrong, Beets, Brazendale and Turner-McGrievy9], and crime [Reference Sorenson, Sinko and Berk10]. Many of these biopsychosocial pandemic adversities may be risk factors for psychosis, for example, loneliness [Reference Michalska da Rocha, Rhodes, Vasilopoulou and Hutton11] and social defeat [Reference Selten, Booij, Buwalda and Meyer-Lindenberg12]. Although research demonstrates that schizophrenia is a risk factor for COVID-19 infection [Reference Wang, Xu and Volkow13,Reference Tzur Bitan, Krieger, Kridin, Komantscher, Scheinman and Weinstein14], the reverse is etiologically plausible. Clinical observations [Reference Harris15–Reference Oh, Park and Song18], theories [Reference Keshavan19,Reference McGrath, Feron, Burne, Mackay-Sim and Eyles20], and research [Reference Dalman, Allebeck, Gunnell, Harrison, Kristensson and Lewis21–Reference Simor, Polner, Bathori, Sifuentes-Ortega, Van Roy and Albajara Saenz23] imply that the multiple biopsychosocial COVID-19 pandemic adversities may increase the risk of schizophrenia. However, the available data are contradictory, indicating both COVID-19 related reductions [Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick and Carreira24,Reference Zielasek, Vrinssen and Gouzoulis-Mayfrank25] and increases [Reference Hu, Su, Qiao, Zhu and YJPd26] in the rate of incident schizophrenia compared to the pre-exposure periods.

To date, four studies have examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on schizophrenia. In the Rhineland region of Germany, based on inpatient service utilization for a range of psychiatric disorders during the first 3 months of the pandemic, results suggested reduced service utilization across all disorders, which was less pronounced for schizophrenia but increased in presentations with atypical psychotic features [Reference Zielasek, Vrinssen and Gouzoulis-Mayfrank25]. Similarly, based on electronic medical records during the first home-confinement period in the UK, a significant reduction in all mental health-related primary and secondary care contacts, including psychosis, was observed [Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick and Carreira24]. In a survey of three European countries during confinement, daily fluctuations of brief psychotic-like experiences increased with associated country-specific COVID-19 deaths [Reference Simor, Polner, Bathori, Sifuentes-Ortega, Van Roy and Albajara Saenz23]. In China, outpatient registry data suggested that the period of COVID-19 was associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia compared to beforehand [Reference Hu, Su, Qiao, Zhu and YJPd26]. These early studies were undertaken early in the pandemic and so could not capture the protracted nature of the multiple biopsychosocial COVID-19 exposures (e.g., cumulative multiple stressors and infection). The studies lack information about incident cases and so we are unable to address whether the biopsychosocial exposures of the COVID-19 pandemic could trigger the onset of schizophrenia. Importantly, their approach did not enable inferences about evolving mental health needs that are critical for planning service provision.

Two-hit models may offer an avenue to explain the onset of the clinical expression of schizophrenia. In these models, first, genetic or environmental insults disrupt early central nervous system development. These early insults invoke long-term vulnerability to a “second hit” that triggers the onset of schizophrenia [Reference Davis, Eyre, Jacka, Dodd, Dean and McEwen27,Reference Maynard, Sikich, Lieberman and LaMantia28]. Plausibly, the biopsychosocial exposures of the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a “second hit.”

In response, the present study used a nationally representative sample to test the “trigger” hypothesis of COVID-19 biopsychosocial stress for schizophrenia. Statistical modeling of the effect of the pandemic was supplemented by robust sensitivity testing to examine the contributions of sociodemographic factors, methodological artifacts, lockdowns, and COVID-19 infection. Importantly, we present data on the predicted post-pandemic incidence of schizophrenia under three different forecast scenarios to assist in planning for emerging health care needs.

Methods

Population

The study source population was nationwide coverage of all Meuhedet members aged between 15 and 64 years. Specifically, electronic health registry data (which are continuously collected and updated) were examed on 736,356 individuals (male N = 371,365, 50.4%; female N = 364,991, 49.6%) aged between 15 and 64 years at the Meuhedet. Meuhedet Healthcare Services (hereafter Meuhedet) is one of the four Israeli health maintenance organizations (HMOs), covered by the Israeli HMO legislation and serves 14% of the total population of Israel nationwide.

The National Health Insurance Law in Israel dictates that four nonprofit public HMOs provide healthcare services to the entire population [Reference Chinitz, Shalev, Galai and Israeli29]. This legislation specifies that all HMOs must offer nationwide services that do not differ financially or in service provision. By law, each Israeli citizen must choose to join a single HMO. HMOs cannot deny residents membership based on location, demographic or medical characteristics (i.e., age, minority-group status, and medical history). Accordingly, noninclusion by an HMO (and hence, sample selection) would violate Israeli legislation. The study received approval from the Meuhedet associated Helsinki Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Exposure

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Israel was on February 27, 2020, and the first lockdown started on March 14, 2020. Accordingly, the interval from January 1, 2013 to February 1, 2020 was classified as the “unexposed period,” and the interval between March 1, 2020 and ending on February 1, 2021 was designated as the “exposed period.” The exposed period covered three COVID-19 waves of government-imposed national COVID-19 attenuation strategies (e.g., lockdowns). These COVID-19 pandemic policy restrictions imposed in Israel during the study period are documented in Table 1 and are based on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker [Reference Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick and Phillips30]. These include the closure of all schools and workplaces, restricted gatherings, staying at home, internal movement restrictions, and banning international travel.

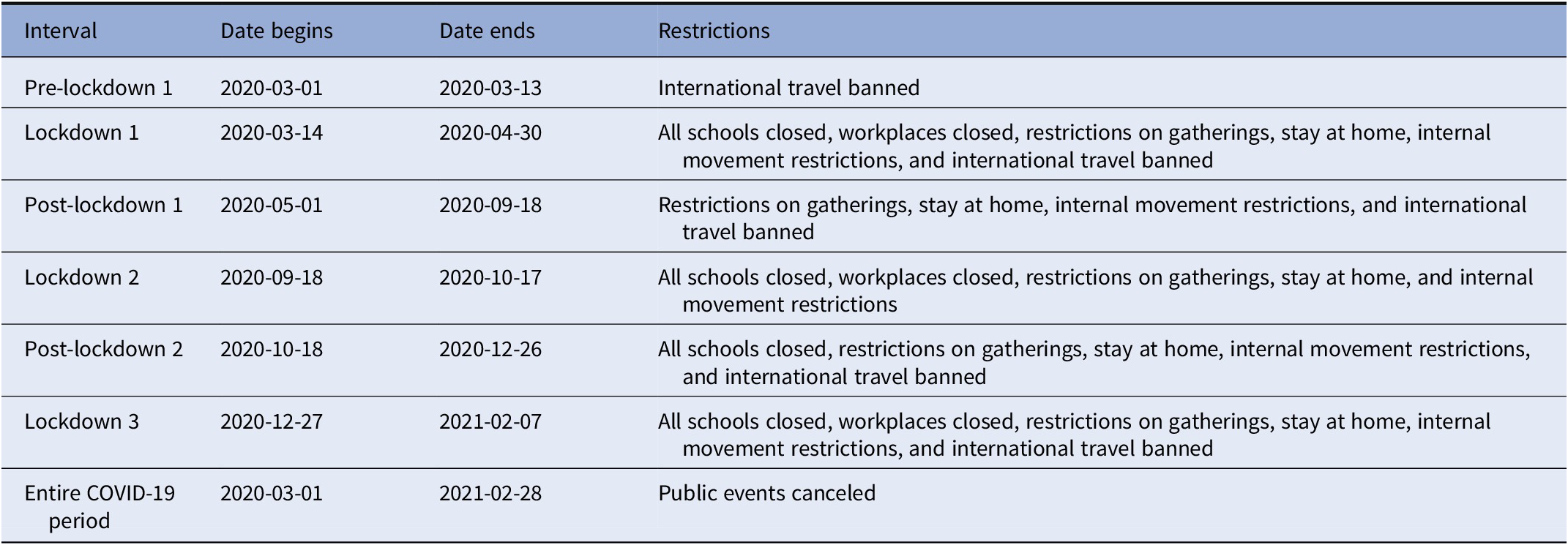

Table 1. COVID-19 Israel policy restrictions.

Note: All schools closed except nurseries. Workplaces closed for all but essential workplaces. Based on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker [Reference Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick and Phillips30] for each interval and each restriction, we compared the mode value of the restriction to a threshold to classify whether the restriction occurred during the interval. For most restrictions, we used the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker threshold value of two, whereas for international travel ban, restrictions on gatherings and workplaces closed, we used a threshold value of three.

Ascertainment of schizophrenia

Monthly incident rates of schizophrenia (including spectrum disorders) were ascertained from ICD codes (version 9: 295–299; version 10: F20–F29) based on diagnoses confirmed by a board confirmed specialist. These diagnoses in this data source were used in prior schizophrenia research [Reference Kodesh, Goldberg, Rotstein, Weinstein, Reichenberg and Sandin31], and the healthcare setting in Israel prevents noninsurance of persons with schizophrenia.

Statistical analysis

We used interrupted time series (ITS, Supplementary Figure S1) [Reference Bhaskaran, Gasparrini, Hajat, Smeeth and Armstrong32–Reference Bernal, Cummins and Gasparrini34], a quasi-experimental study design [Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell35], to compare the monthly incident schizophrenia rates between the exposed and unexposed periods [Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick and Carreira24–Reference Hu, Su, Qiao, Zhu and YJPd26]. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders trends were examined for distinct changes from preexisting trends, termed a counterfactual. This study design is instrumental when retrospective evaluations of population-level interventions are required. The ITS modeled time (as a monthly sequence during the entire 7-year period of the study period), exposure period (i.e., unexposed or exposed), and their interaction. Additional covariates were an offset term to model event rates and seasonal Fourier terms to model the seasonal factors.

For the primary analysis, to compare the intervals unexposed and exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic, we fitted a Poisson regression model and quantified the relative risk (RR) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the total monthly incident schizophrenia rate. The RR compares the model predictions for the exposed period to the model predictions for the same period but under the assumption that COVID-19 had not occurred (i.e., the counterfactual), accounting for the study covariates.

For public health policy post-wave three, we extended the primary Poisson regression model to forecast post-wave three schizophrenia incident rates from March 1, 2021 to December 1, 2021, under three scenarios (a) assuming no ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; (b) assuming ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; and (c) were estimated based on the periods both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The robustness of the primary analysis results was challenged in 12 sensitivity analyses. The first set focused on sex and socioeconomic status (SES; defined in Supplementary Material) which are known modifiers of schizophrenia risk [Reference Aleman, Kahn and Selten36,Reference Werner, Malaspina and Rabinowitz37]. The second set examined potential methodological artifacts, including seasonal decompositions, and unit of time from a month to a 15-day interval to test for the potential artifact of aggregation. We used the incident rates of schizophrenia before and during the Gaza war as a negative control group to consider potential confounding and bias [Reference Lipsitch, Tchetgen and Cohen38]. This war (July 8–August 24, 2014) may also be considered as a “traumatic” event by the Israeli population due to military and civilian fatalities and severe rocket bombing. The final series of sensitivity analyses focused on the impact of the severity of social restriction and of COVID-19 infection status. Accordingly, we tested for potential differences in schizophrenia incident rates during the lockdown-on and lockdown-off periods based on 15-day intervals and between COVID-19 positive and negative cases for equality of proportions [Reference Hogg and Tanis39]. Finally, we conducted an additional ITS, like the primary analysis, restricted only to individuals who did not test positive for COVID-19 in each month. Analyses were implemented in R [40], with the packages forecast [Reference Hyndman and Khandakar41], and ggplot2 [Reference Wickham H.42].

Results

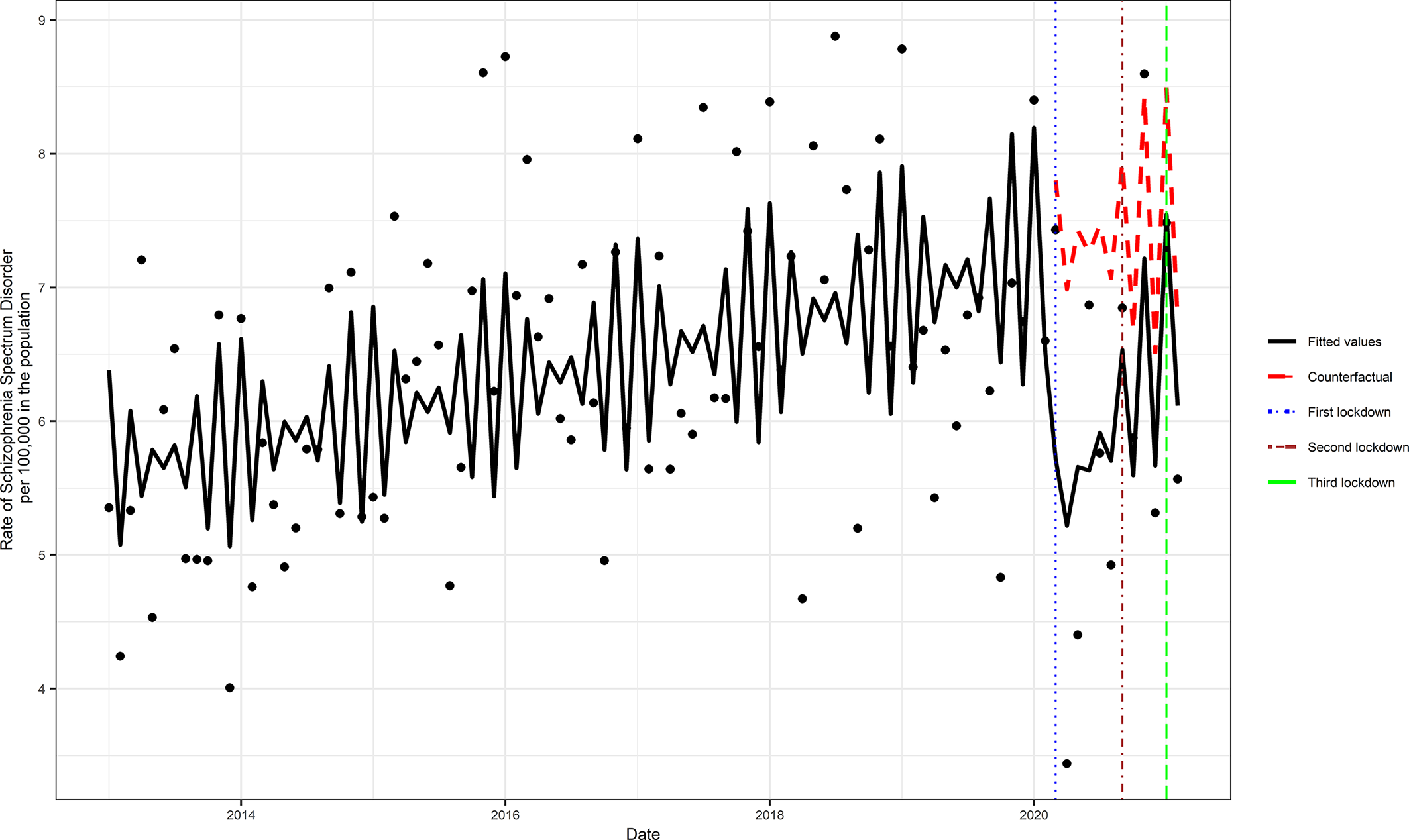

We identified a total of 4,310 incident cases of schizophrenia (total cumulative rate per 100,000 = 585.31, 95% CI = 567.97, 603.06) across the study period. The monthly incident rate of schizophrenia across the study intervals ranged from 3.40 (CI 2.20, 5.01) to 8.56 (CI 6.57, 10.95) per 100,000 in the population. Although the trend in the incident rate in schizophrenia increased before the COVID-19 pandemic, the primary analysis showed that during the exposed period there was a statistically significant (RR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.73, 0.91, p < 0.001) reduction in the incidence of schizophrenia (Figure 1). The model assumptions were not violated by residual autocorrelation and residual partial autocorrelations (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1. Comparison of the periods with and without Covid-19 pandemic exposure. The counterfactual refers to the predicted values had no COVID-19 occurred, and the fitted values are estimated based on the Poisson regression model.

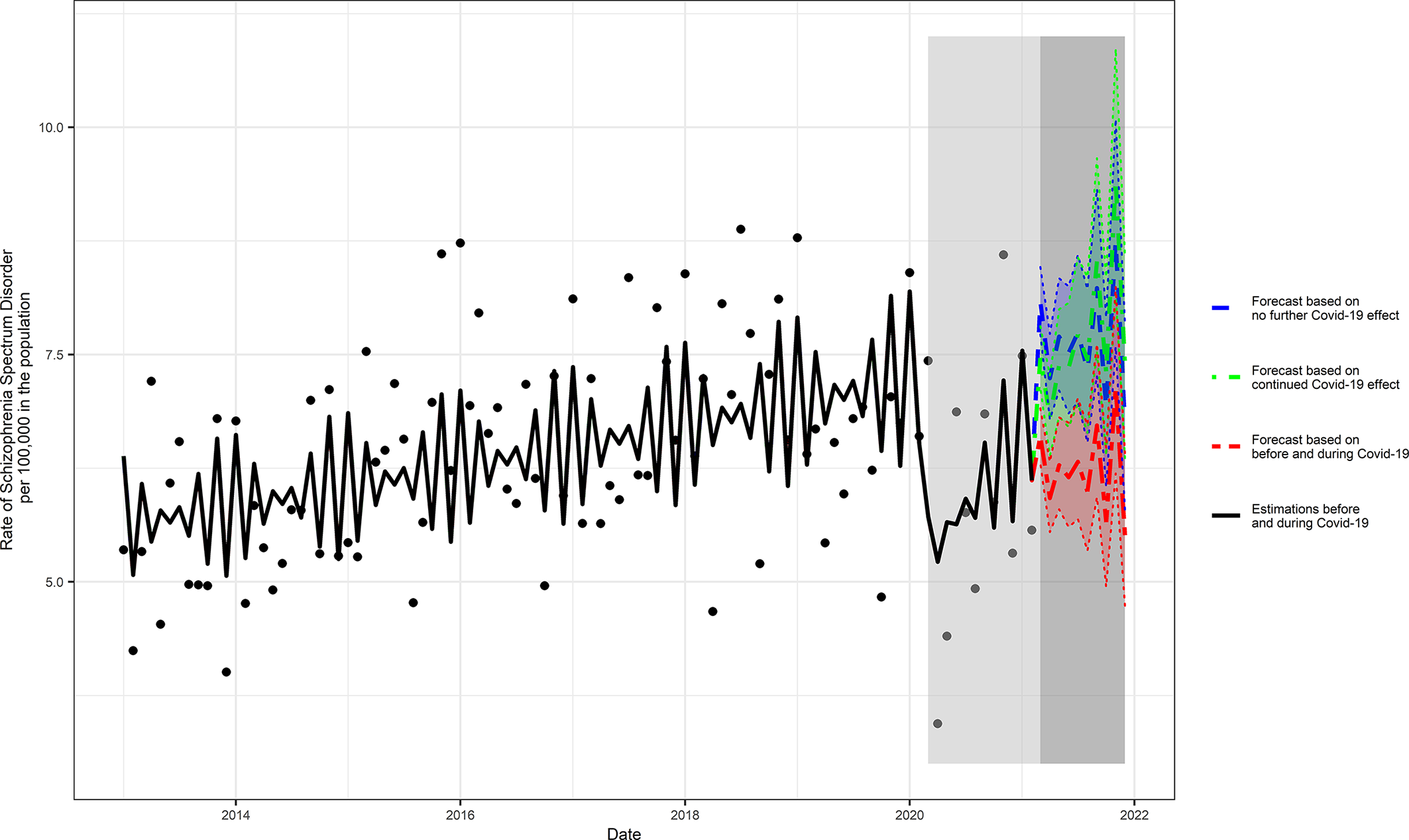

The median incidence rate of schizophrenia during the unexposed period was 6.43 per 100,000 in the population. Predicted 10-month estimates of schizophrenia incidence post-March 2021 ranged from 6.74 (95% prediction intervals [PI] = 5.80, 7.84), assuming no ongoing COVID-19 pandemic effect, to 7.40 (95% PI = 6.36, 8.60) assuming an ongoing pandemic effect; the scenario based on the intervals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic exposure yielded an estimate of 5.51 (95% PI = 4.74, 6.42) (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2. Three scenarios of forecasted COVID-19 pandemic effects on the rate of schizophrenia. The following three scenarios were scrutinized (a) assuming no ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; (b) assuming ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic; and (c) based on the intervals before and during COVID-19 pandemic.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses restricted to males, females as well as low, medium, and high SES confirmed the results of the primary analyses (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Seasonal adjustments (Supplementary Figure S5) and changing the underlying time scale to 15-day intervals (Supplementary Figure S6, top panel) yielded comparable point precision estimates to the primary analysis. The Gaza war had no statistically significant effect on schizophrenia incidence rates, whereas the COVID-19 pandemic had a statistically significant decrease in schizophrenia incidence rates (Supplementary Figure S7 and Supplementary Table S2).

No differences in the incidence of schizophrenia were noted when comparing the lockdown-on and lockdown-off periods (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Figure S8 and Supplementary Table S2). Similarly, no difference in the proportions of the incidence of schizophrenia was noted when COVID-19 positive cases were compared to those who were COVID-19 negative (difference = 10−5[−5.13], 95% CI = 10 −5 [−7.6,−2.66], p-value = 0.06). Third, sensitivity analysis restricted only to those with no evidence of COVID-19 infection yielded comparable point-precision estimates to the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure S9 and Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

We leveraged electronic medical record data collected using an epidemiological framework with national coverage to conduct an ITS analysis to test for the effect of biopsychosocial exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic on the incident rate of schizophrenia. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine incident rates throughout the three waves of the pandemic while addressing sociodemographic features, the severity of social restrictions, and the COVID-19 infection status.

Despite the increasing time trend during the unexposed period before the pandemic, we found that the schizophrenia incidence rate dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic. Forecasting scenarios indicated that after COVID-19 pandemic-related mitigation strategies are lifted, the incidence of schizophrenia is likely to increase over 10 months.

The forecasting models suggest that the most likely future outcome is that the incidence of schizophrenia will increase even if there are no lingering biopsychosocial pandemic effects. This may be relevant, as most social mitigation strategies were lifted within Israel at the end of the data collection for this study. More than half of the Israeli population is now fully vaccinated, and economic recovery is expected, at least in the immediate aftermath of the third wave of the pandemic [43]. Hence, the end of the pandemic restrictions may signify a period of increased service needs for psychosis. This result may or may not generalize to other nations that are without restrictions at this time (e.g., the UK).

A unique feature of our study was the scrutiny of different COVID-19 pandemic related biopsychosocial exposures on the schizophrenia rate in sensitivity analyses. The results of sensitivity analysis included analyses restricted to different SES groups that replicated the primary results, analysis restricted to non-COVID-19 cases which replicated the primary results, COVID-19 lockdown status that given the exposed period had a null impact on the schizophrenia rate, and a negative control period of war that had a null impact on the schizophrenia rate. The current findings of different effects of the Gaza war and the COVID-19 pandemic periods suggest that it is inappropriate to generalize between large-scale traumatic events. Nonetheless, future research is warranted to compare the COVID-19 pandemic with other disasters. Collectively, it appears that the unique psychosocial factors, rather than the infection or lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly impacted the schizophrenia rate.

The reduction in the incidence of schizophrenia during the pandemic may reflect reduced service use because of social restrictions and hence reduced opportunities for diagnostic assessments. This interpretation aligns with evidence from other studies that have noted an overall reduction of health service contacts across both physical and mental diagnoses [Reference Mansfield, Mathur, Tazare, Henderson, Mulick and Carreira24]. Also, during the pandemic, the nature of health consultations changed with a rapid transition to digital platform use. It is theoretically possible that diagnoses of psychosis may have been missed because of this change of format. Other possibilities involve changes in family function during the pandemic, with families spending more time together than they would typically before the social restriction policies were in place. Furthermore, new-onset primarily affects young people, many of whom may have had to remain or return to their nuclear families as universities closed to in-person teaching or job opportunities away from home became scarce. At least for some young people, these changes may have been protective. However, causal mechanistic insights are not possible based on observational data alone but suggest important avenues for future research. Further research from other countries is required to test the generalizability of the present findings, although the initial available suggests similar trends, at least regarding mental health service contacts.

Limitations

Causal conclusions are not possible based on observational data like ours, and it is not possible to eliminate residual confounders (e.g., occupations at risk). However, we examined groups with possibly differential schizophrenia risks, used a quasi-experimental study design, and an experiment of schizophrenia risk with COVID-19 would be unethical. Second, circumstances specific to Israel limit generalizing our results to other nations. For instance, in the first wave, Israel had a comparatively low COVID-19 mortality rate, a high number of COVID-19 cases, and entered the second wave and lockdown sooner than other nations [Reference Greener44]. Nonetheless, this limitation is balanced by the results considering three waves of COVID-19, and COVID-19 infection status.

Our results, for the first time, argue against COVID-19 infection having a direct pathogenetic effect for psychosis. It is plausible that a delayed effect occurred in the development of schizophrenia. We could not address this possibility owing to a lack of follow-up. Thus the results presented here are not conclusive, and replication is warranted. Similarly, owing to policy changes to address and variants of COVID-19, continued monitoring of the incidence of schizophrenia and related disorders is required to test for the possibility of a delayed direct effect and to test the accuracy of our predictions.

We implemented a quasi-experimental study design of unselected nationally representative cohort with little missing data, where the biases of selection and attrition are unlikely to explain our findings. The primary analysis reinforced by rigorous sensitivity analyses showed that exposure to the psychosocial adversities of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a reduced RR of schizophrenia. However, within 10 months after the COVID-19 pandemic and without COVID-19 restrictions in place, it is forecast that the schizophrenia rate will increase.

Data Availability Statement

Data access is possible following the processing of a reasonable request.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2245.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.T.-L., Y.G., A.R., S.F., S.Z.L.; Data curation: Y.T.-L., A.K., Y.G., S.Z.L.; Formal analysis: Y.G., S.F., S.Z.L.; Investigation: A.K., Y.G., A.R., S.F., S.Z.L.; Methodology: Y.T.-L., A.K., Y.G., A.R., S.F., S.Z.L.; Project administration: A.K.; Supervision: Y.G., S.F., S.Z.L.; Validation: A.K.; Visualization: Y.T.-L.; Writing—original draft: Y.T.-L., A.K., S.F., S.Z.L.; Writing—review and editing: Y.T.-L., A.K., Y.G., A.R., S.F., S.Z.L.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.