Introduction

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is one of the most influential developmental stages across the lifespan [Reference Schulenberg, Sameroff and Cicchetti1]. Adolescence is a critical period for neurodevelopment, when over half of all lifetime psychiatric disorders begin [Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2, Reference Fusar-Poli, Correll, Arango, Berk, Patel and Ioannidis3]. Mental disorders account for approximately 45% of the global disease burden in adolescents [Reference Gore, Bloem, Patton, Ferguson, Joseph and Coffey4], and are associated with multiple developmental concerns (e.g., lower educational achievement; [Reference Patel, Flisher, Hetrick and McGorry5]). Research on adolescents suggests that contact with mental health professionals has preventive effects against psychiatric disorders [Reference Stockings, Degenhardt, Dobbins, Lee, Erskine and Whiteford6, Reference Neufeld, Dunn, Jones, Croudace and Goodyer7] and is cost-effective [Reference Mihalopoulos and Chatterton8]. However, surveys estimate that approximately 67% of adolescents needing services, as defined by the presence of a psychiatric disorder, neither seek nor receive formal help [Reference Costello, Copeland, Cowell and Keeler9].

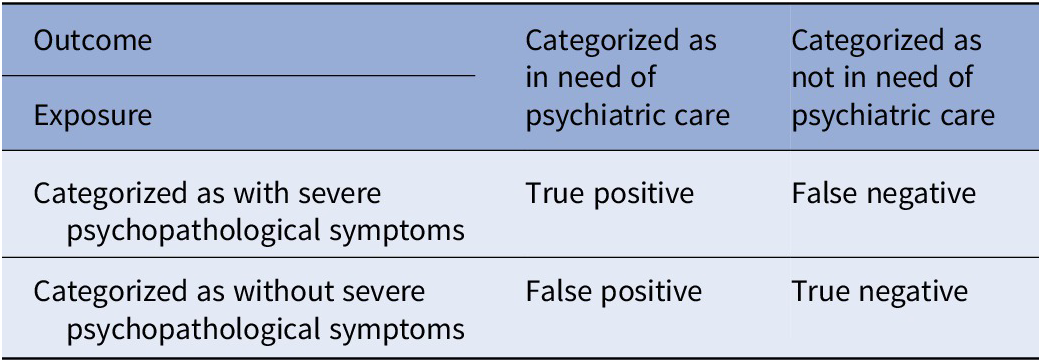

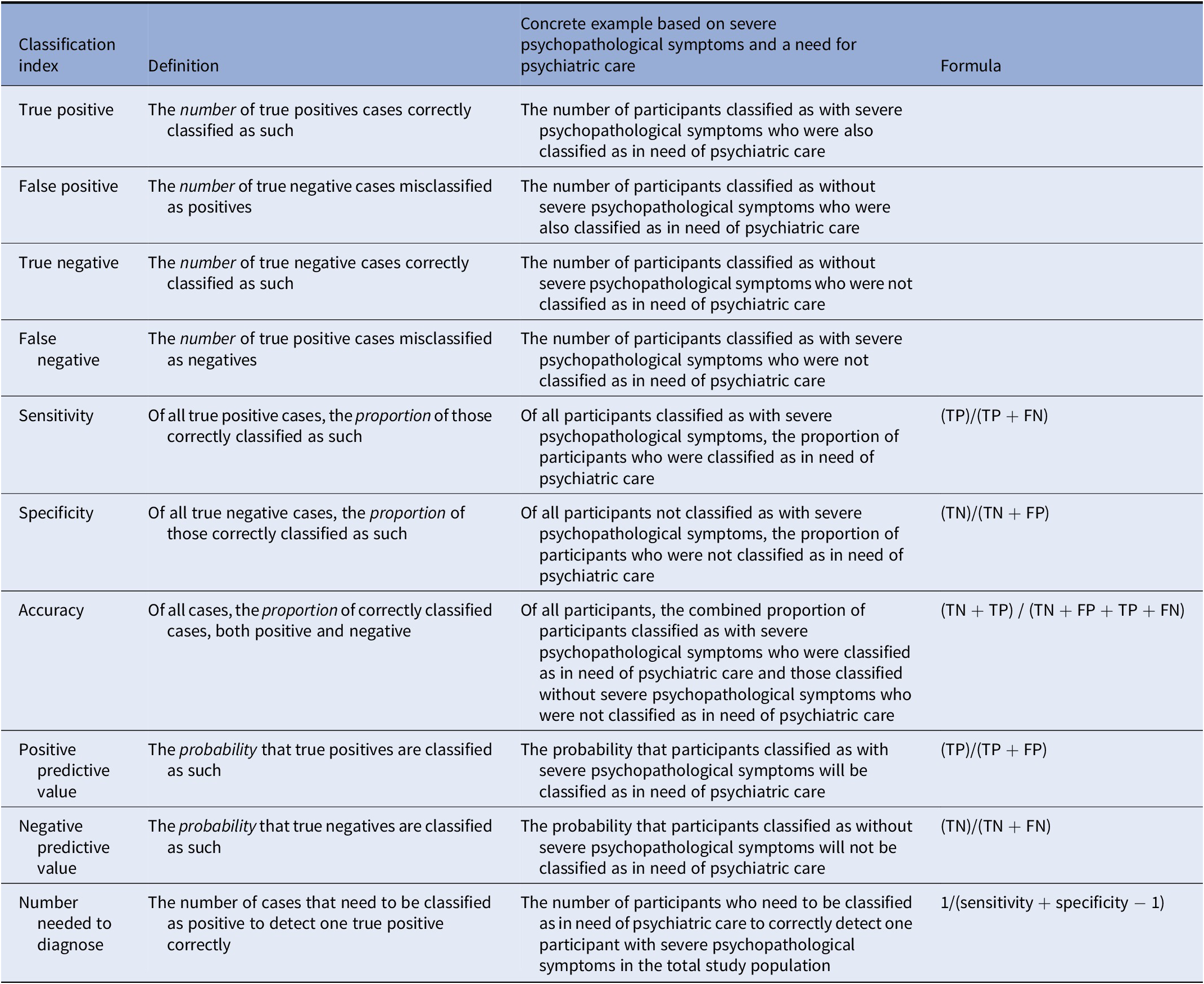

Widespread methodological limitations in the literature appear to obscure the avenues to investigate prevention strategies for adolescents at-risk. First, most existing research is based on restricted care access due to financial and regional barriers [Reference Paula, Bordin, Mari, Velasque, Rohde and Coutinho10]. Financial resources for adolescent mental health care are insufficient and mental health services for adolescents are most likely less than are needed [Reference Rocha, Graeff-Martins, Kieling and Rohde11]. A major challenge in this area is the shortage of mental health professionals [Reference Patel, Flisher, Hetrick and McGorry5]. Furthermore, mental hospitals, which are the main axis of mental health care, are found in major cities only [Reference Levav and Grinshpoon12] thus forming regional barriers. To date, no study has examined unrestricted mental health care access in adolescents. Unrestricted access to mental health care is based on the notion that mental health care should be accessible to all persons at all times and locations [Reference Smith, Embling, Price and Alty13]. Second, most studies include informal mental health resources rather than focusing on specialized mental health professionals [Reference Mansbach-Kleinfeld, Farbstein, Levinson, Apter, Erhard and Palti14]. Informal mental health resources include all nonprofessional sources available in the community (e.g., friends; [Reference Mansbach-Kleinfeld, Farbstein, Levinson, Apter, Erhard and Palti14]). Although informal mental health resources form a broader measure of mental health care, they may not provide effective treatment [Reference Mansbach-Kleinfeld, Farbstein, Levinson, Apter, Erhard and Palti14]. Third, no study has examined clinically relevant classification indices. Classification indices quantify the extent a binary exposure (e.g., surpassing a symptom threshold) overlaps with a binary outcome (e.g., the need for psychiatric care). The classification model is usually presented through a standard two by two tables (Table 1; [Reference Ruhrmann, Schultze-Lutter, Salokangas, Heinimaa, Linszen and Dingemans15]) and its attributes can be measured based on several indices (Table 2; [Reference Ruhrmann, Schultze-Lutter, Salokangas, Heinimaa, Linszen and Dingemans15]). Classification indices facilitate the quantification of the performance of different measures and therefore play an influential role in the assessment of diagnostic effectiveness. These indices form the basis for the decision of whether to implement early detection and prevention measures in clinical practice [Reference Adams and Leveson16].

Table 1. Classification model: severe psychopathological symptoms and need of psychiatric care.

Table 2. Description of the classification indices.

Abbreviations: FN, false negative; FP, false positive; NND, number needed to diagnose; NPV, negative predictive values; PPV, positive predictive values; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

The current study aims to capture adolescents in need of psychiatric care with psychopathological symptoms, focusing on clinically relevant classification measures. This study is based on an adolescent cohort in a setting without any health access inequalities, psychometric assessments of psychopathological symptoms, and external referrals to mental health professionals.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Haifa granted ethical approval to conduct the study with a waiver of informed consent (Application no. 090/21).

Study population and procedure

Adolescents in Israel undergo a mandatory predraft screening by the Israeli Draft Board at age 16–17 years to ascertain their eligibility to serve in the military. This assessment includes individuals who are eligible for military service, as well as those who will be excused from service based on medical, psychiatric, or social grounds. The study sample (N = 1,421), provided by the Israeli Draft Board, included any individual coming in for a standard mandatory screening on randomly selected days in 2017, with a minimal Hebrew language proficiency level. For the analytic sample, we excluded individuals older than 17 (N = 52) leaving a sample of 1,369 (average age of 16.96; SD = 0.22). See Supplementary Figure S1 for a flow diagram. Participants were administered a self-report psychopathological symptoms questionnaire, a computerized intellectual assessment, and a behavioral screening interview. Based on the screening interview, adolescents with a suspected psychiatric disorder were referred to a mental health professional and defined as in need of psychiatric care. Data were retrieved from computerized military files.

Psychopathological symptoms

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; [Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos17]) is a self-report measure used to identify clinically relevant psychopathological symptoms in adolescents and adults. It consists of 53 items covering nine symptom dimensions: somatization, obsession–compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Ratings characterize the intensity of distress during the past month. An adapted version of the BSI was supplemented with five items to cover two more dimensions: drug use and self-harming behaviors. All items were responded to on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The measure took approximately 10–12 min to complete. The internal reliability reported for this measure, based on a previous sample of adolescents, was satisfactory (alpha = 0.95 for the general severity index; average alpha = 0.71 for all BSI subscales) as was the convergence validity with the General Well-Being questionnaire [Reference Fazio18] (r = −0.62 for the general severity index; average r = −0.49 for all BSI subscales) [Reference Canetti, Shalev and De-Nour19].

Intellectual assessment

The Israeli Draft Board intellectual assessment includes four cognitive tests that measure verbal understanding and abstraction, categorization abilities, mathematical reasoning, and visual–spatial problem-solving abilities. The summary score of the cognitive test battery has been found to be a highly valid measure of general intelligence as measured by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [Reference Wechsler20] total score (r > 0.90). The results of the intellectual assessment were further significantly correlated with external measures (i.e., rank upon discharge; r > 0.41) [Reference Gal21]. This intellectual assessment has been used in many other studies [Reference Reichenberg, Weiser, Rapp, Rabinowitz, Caspi and Schmeidler22–Reference Reichenberg, Weiser, Rapp, Rabinowitz, Caspi and Schmeidler25].

Need for psychiatric care

An interview assessing personality and behavioral traits was administered by college-aged individuals who participated in a four-month-long training course on the administration of the interview These administrators, affiliated with the Behavioral Science Division, are routinely overseen by professional mental health specialists [Reference Reeb26]. Based on the interview and on findings from a general physician’s examination, adolescents who were suspected of having behavioral disturbances or mental illnesses were referred to an in-depth assessment by a mental health professional (a clinical social worker or psychologist, affiliated with the Mental Health Division). Criteria for referral to an in-depth mental health assessment include a history of psychological or psychiatric treatment or complaints, manifestation of behavioral abnormalities during the physician’s examination or the screening interview, or obtaining the lowest score on the rating of social functioning in the screening interview [Reference Weiser, Reichenberg, Rabinowitz, Kaplan, Mark and Bodner27]. The test–retest reliability of the screening interview, made after several days by different interviewers, was high (>0.8) as was its validity in predicting external measures (i.e., rank after 30 months of military service; r = 0.39) [Reference Gal21, Reference Reeb26].

Data analyses

First, data were screened for missing values and completeness. Second, the primary analysis was conducted. Previous research has found that the percentages of patients attaining levels of high distress on the nine BSI scales are up to 10% (highest being 9.5%) [Reference Stefanek, Derogatis and Shaw28]. Therefore, BSI scores were categorized as severe if they were in the top 10th percentile of symptoms, otherwise not severe. Logistic regression models were fitted to quantify the association between severe psychopathological symptoms and the need for psychiatric care with odds ratios (OR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). Logistic regression models were computed for total BSI scores and for each of the eleven subscales (because certain disorders are stronger indicators of a need for care; [Reference Wu, Hoven, Bird, Moore, Cohen and Alegria29]) unadjusted (without covariates) and adjusted for covariates (age, sex, and the total intellectual assessment score). Next, the utility of severe psychopathological symptoms for clinical prediction of need for psychiatric care was ascertained based on classification indices of each adjusted logistic regression model (Tables 1 and 2). There are no clear guidelines regarding sufficient sensitivity and specificity [Reference Boyko30], although values of 90% and over may be considered to be sufficiently reliable as to have public health policy implications.

Third, to test the robustness of the primary analysis, sensitivity analyses were conducted, restricted to relevant subgroups of participants: participants with a low intellectual assessment score, defined as lower than two standard deviations under the population mean (because lower intellectual ability is related to severe mental disorders; [Reference Reichenberg, Weiser, Rapp, Rabinowitz, Caspi and Schmeidler22, Reference Reichenberg, Velthorst and Davidson31]); as well as males and females (because a previous Israeli study based on a nationwide representative sample has shown that females tend to report higher levels of symptoms than males; [Reference Gilbar and Ben-Zur32]). Each sensitivity analysis repeated the primary analysis, except the covariate that the analysis was restricted to was dropped. Finally, to ensure the results were not an artifact of the use of 10% as a symptom severity categorization threshold, we reanalyzed the data by altering the BSI symptomatic threshold to 20% (because previous research has found that the percentages of patients attaining levels of moderate distress on the nine BSI scales average to about 20%; X = 19.75) [Reference Stefanek, Derogatis and Shaw28]. All analyses were computed in R version 4.1.0 [33].

Results

Sample characteristics

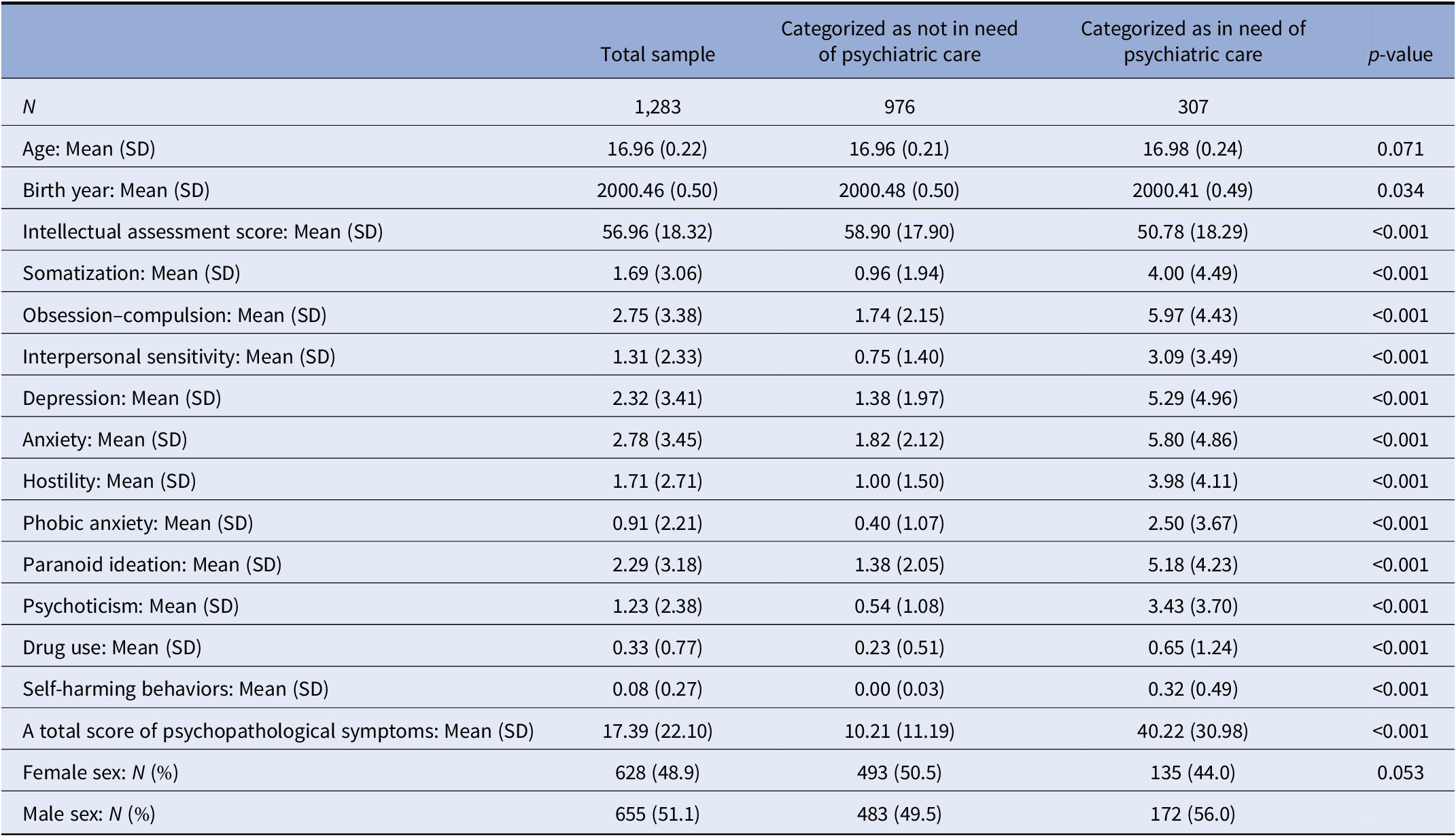

Individuals with missing data on sex (N = 67), intellectual assessment (N = 18) and psychopathological symptoms (N = 1) were excluded (6.28% missing in total; N = 86) leaving a total of 1,283 adolescents for analysis. Characteristics of the analytic sample show statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between adolescents in need of psychiatric care and those who are not (Table 3).

Table 3. Sample characteristics.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Severe psychopathological symptoms and the need for psychiatric care

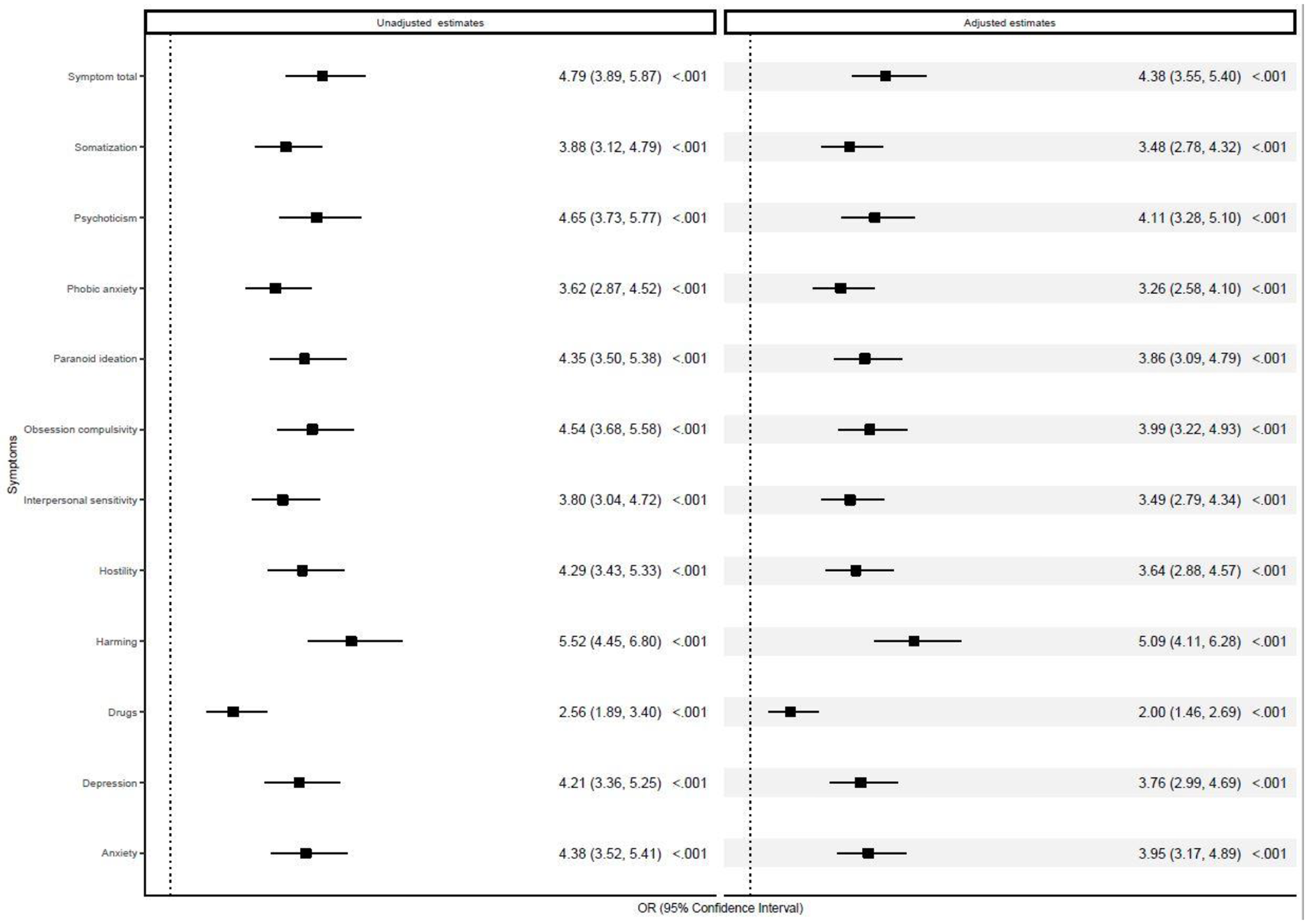

A total of 9.67%(N=124) of adolescents were categorized as with severe psychopathological symptoms (based on the unadjusted top 10th percentile of the total symptoms score), of whom 83.87%(N=104) were categorized as in need of psychiatric care. Of those adolescents categorized without severe psychopathological symptoms (N=1159), 17.52% (N=203) were identified as in need of psychiatric care (Supplementary Table S1). Logistic regression modeling showed that adjusted severe psychopathological symptoms were associated with a 4.4-fold increase in the need for psychiatric care compared to non-severe psychopathological symptoms (95% CI:3.55, 5.40, p<0.001; unadjusted HR=4.79; 95% CI: 3.89, 5.87, p<0.001). Results were similar for all (adjusted and unadjusted) psychopathology subscale scores (Figure 1) and remained statistically significant (p < 0.05) across all sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Tables S2–S5).

Figure 1. Logistic regression modeling: severe psychopathological symptoms and the need for psychiatric care. OR, odds ratio. Logistic regression models were computed unadjusted (without covariates) and adjusted for age, sex, and the total intellectual assessment score.

The utility of severe psychopathological symptoms for clinical prediction of need for psychiatric care

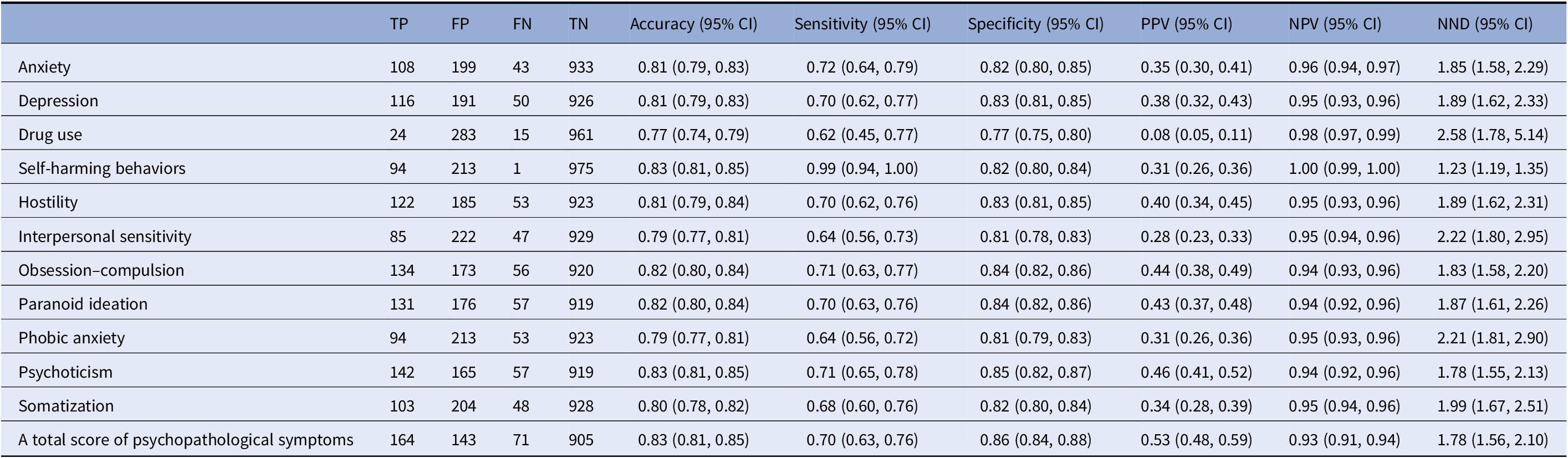

Severe psychopathological symptoms had an adjusted classification accuracy of 83% (95% CI: 81%, 85%), sensitivity of 70% (95% CI: 63%, 76%), specificity of 86% (95% CI: 84%, 88%), a positive predictive value of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.48, 0.59), a negative predictive value of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91, 0.94) and a number needed to diagnose of 1.78 (95% CI: 1.56, 2.10). Analyses of the eleven symptom subscales point to an accuracy rate lower than 84% (Table 4). Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the performance of severe psychopathological symptoms for clinical prediction of need for psychiatric care was generally insufficient for participants with a low intellectual assessment score, males, females, and with a symptom severity categorization threshold of 20% (Supplementary Tables S6–S9).

Table 4. Adjusted classification indices estimating the utility of severe psychopathological symptoms for clinical prediction of need for psychiatric care.

Note: The classification indices were adjusted for age, sex, and the total intellectual assessment score.

Abbreviations: FN, false negative; FP, false positive; NND, number needed to diagnose; NPV, negative predictive values; PPV, positive predictive values; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

Discussion

Based on an adolescent cohort in a unique setting characterized by equal and unrestricted access to mental health professionals, we aimed to capture adolescents in need of psychiatric care with psychopathological symptoms. The results showed strong statistically significant (p < 0.001) associations between severe psychopathological symptoms and the need for psychiatric care. However, the clinical utility of self-reported psychopathological symptoms for classification purposes was not supported. These results were identified in a large population-based cohort of adolescents and found robust across different demographic subpopulations.

Severe psychopathological symptoms were associated with the need for psychiatric care, which is consistent with prior observational studies of children (e.g., [Reference Merikangas, He, Brody, Fisher, Bourdon and Koretz34]). However, psychopathological symptoms did not adequately capture adolescents in need of psychiatric care. Specifically, two thirds (66.12%) of all adolescents in need of psychiatric care were classified as without severe psychopathological symptoms, and roughly one in six (16.13%) of those classified with severe psychopathological symptoms was not classified as in need of psychiatric care. Similar to prior prodromal research (e.g., [Reference McGorry, McKenzie, Jackson, Waddell and Curry35]), our study data showed that self-reported severe psychopathological symptoms were unreliable for classification purposes. Self-reported severe psychopathological symptoms, although accounting for a fair proportion of treatment seeking, would perhaps be better useful alongside other variables (e.g., early life risk factors; [Reference Reichenberg and Levine36]) to identify adolescents at-risk.

Limitations

The current study has some limitations. First, this study is based on traditional psychiatric taxonomies that are restricted in capturing the complexities of emerging mental disorders [Reference Shah, Scott, McGorry, Cross, Keshavan and Nelson37]. While new approaches are needed to generate clinical definitions that both recognize the fluid developmental course of mental illnesses and are suitable for implementation, these taxonomies still dominate the international classification systems [Reference Shah, Scott, McGorry, Cross, Keshavan and Nelson37]. Second, the current study identified clinically relevant psychopathological symptoms with the BSI [Reference Derogatis and Melisaratos17]. Hence we cannot ascertain the extent to which the current results would replicate using other measures, such as the Child Behavior Checklist [Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock38], the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [Reference Goodman39], or the Development and Well-Being Assessment [Reference Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward and Meltzer40]. Third, our conclusions with regards to psychopathological symptoms are restricted to self-reports. Past research has shown that the prevalences of self-reported psychopathological symptoms in children and adolescents is much higher than those reported by external evaluators [Reference Tepper, Liu, Guo, Zhai, Liu and Li41]. Had clinical assessments been available, different conclusions may have emerged. Fourth, the prevalence of symptomatology ascertained by the symptom screener is based on the last month. Perhaps screening for a lifetime history would have increased the classification rates, although it may superfluously increase the rate by introducing more memory recall biases [Reference Songco, Booth, Spiegler, Parsons and Fox42]. Fifth, psychopathological symptoms were categorized as severe if they were in the top 10th percentile of symptoms (otherwise not severe), leaving our study vulnerable to the limitations of dichotomization (e.g., loss of information [Reference Altman and Royston43]). However, in clinical and observational studies, cut-offs are widely used to ascertain severity [Reference Jones, Stergiakouli, Tansey, Hubbard, Heron and Cannon44], and to compute widely understood clinically values like the Number Needed to Treat [Reference Vancak, Goldberg and Levine45]. Also, the current study analysis showed consistent results across cut-off thresholds, indicating that these are quite robust thresholds worthy of future research. Sixth, the sample size prohibited the scrutinization of adolescents with a specific diagnosis due to insufficient statistical power. We, therefore, analyzed a sample of participants with a vast array of reported symptoms and accounted for age, sex, and intellectual ability. Seventh, we did not test for multiple comparisons within the BSI subscales because it may lead to errors of interpretation [Reference Rothman46]. Eighth, our study did not include hold-out data (i.e., a portion of the data that is not included in the analytic data set for validating research models). Given the combination of relatively rare-exposure (severe psychopathological symptoms) and rare-outcome (referral to a mental health professional) in our data, the primary model approach was chosen without a hold-out mechanism to ensure a reasonable level of statistical power. Future research with a prospective cross-validation sampling design is warranted to examine the role of psychopathological symptoms as a proper clinical prediction tool.

Summary

The current study is the first prospective study of adolescents with unrestricted professional mental health care access that accounts for intellectual abilities and examines classification indices. The results show consistent, strong, and statistically significant associations between severe psychopathological symptoms and the need for psychiatric care. However, in our study data, self-reported severe psychopathological symptoms were unreliable for classification purposes required to implement mental health care policies. Self-reported severe psychopathological symptoms, although accounting for a fair proportion of treatment seeking, would perhaps be better useful alongside other variables (e.g., poverty and social disadvantage [Reference Patel, Flisher, Hetrick and McGorry5]) rather than in isolation.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2251.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available. Data may be requested from J.G. and S.F., and pending approval from the Department of Behavioral Sciences, Israel Defense Forces, Israel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: An.R., J.G., S.F., S.Z.L., Ab.R.; Data curation: An.R., J.G., S.F., S.Z.L., Ab.R.; Formal analysis: An.R., S.Z.L.; Funding acquisition: NA; Investigation: An.R., S.Z.L., Ab.R.; Methodology: An.R., J.G., S.F., S.Z.L., Ab.R.; Project administration: J.G., S.F., Ab.R.; Resources: NA; Software: An.R., S.Z.L; Supervision: Ab.R.; Validation: S.Z.L., Ab.R.; Visualization: S.Z.L.; Writing—original draft: An.R.; Writing—review and editing: An.R., J.G., S.F., S.Z.L., Ab.R.

Financial Support

An.R. is supported by the Zuckerman-CHE Israeli Women Postdoctoral Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.