1. Introduction

In the general child population, cognitive ability and psychopathology (usually measured by problem behaviour, in turn indexed by internalising and externalising problems) vary with time and are related to one another contemporaneously. However, it is not known how they may be associated with one another over time. For example, it is not known if they reciprocally influence one another or if one causes the other. As a result, the developmental cascades of internalising problems, externalising problems and cognitive ability in childhood are yet to be examined.

There is certainly much research into how two of the three domains (internalising and externalising problems) are inter-related concurrently and longitudinally in children [Reference Boylan, Georgiades and Szatmari1–Reference Hatoum, Rhee, Corley, Hewitt and Friedman8]. For example, many studies - usually situated in social developmental psychology - have shown that in childhood externalising problems increase internalising problems, in line with expectations from the failure theory whereby noxious behaviours and lack of social skills alienate peers which, in turn, increases vulnerability to internalising symptoms [Reference Gooren, van Lier, Stegge, Terwogt and Koot2]. Explanations when effects are not found [Reference Morin, Arens, Maïano, Ciarrochi, Tracey and Parker4, Reference Van der Ende, Verhulst and Tiemeier9] vary but one may be that mixed findings are due to the inappropriate or inconsistent treatment of third variables such as mediators or confounders. In general, however, most studies exploring the developmental cascades of internalising and externalising problems in childhood show that externalising problems increase internalising problems or that the two mutually reinforce each other [Reference Boylan, Georgiades and Szatmari1, Reference Gooren, van Lier, Stegge, Terwogt and Koot2, Reference Van der Ende, Verhulst and Tiemeier9, Reference Moilanen, Shaw and Maxwell10].

Although, as explained, no study has yet examined the longitudinal associations between internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores, studies have examined prospective links between internalising and externalising problems and constructs related to cognitive ability such as academic competence [Reference Weeks, Ploubidis, Cairney, Wild, Naicker and Colman11] or, usually, academic performance. Most have shown a negative direct link from externalising problems to later academic performance but also a mixed picture of how academic performance is associated with externalising and internalising problems longitudinally [Reference Van der Ende, Verhulst and Tiemeier9, Reference Moilanen, Shaw and Maxwell10, Reference Englund and Siebenbruner12–Reference Verboom, Sijtsema, Verhulst, Penninx and Ormel17]. For instance, some studies suggest that there is a direct negative link between academic performance and later internalising and externalising problems [Reference Moilanen, Shaw and Maxwell10, Reference Englund and Siebenbruner12, Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku15, Reference van Lier, Vitaro, Barker, Brendgen, Tremblay and Boivin16], some suggest absence of any significant associations between academic performance and internalising problems, and others suggest that academic performance might act as a partial mediator between externalising and later internalising problems [Reference Masten, Roisman, Long, Burt, Obradović and Riley13]. In addition, by focussing on academic performance these studies have excluded the early years, when knowledge about causal processes, and therefore recommendations about interventions, may be particularly important. Finally, although related, cognitive ability and academic performance are distinct constructs [Reference Johnson, McGue and Iacono18]. Cognitive ability is one of the strongest predictors of academic performance, but the latter is also independently associated with other genetic and environmental factors, including self-regulation, socioeconomic and schooling characteristics and the home learning environment [Reference Blair and McKinnon19].

We aimed to bridge this gap by examining in this study cascading processes among internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores in a large general-population UK sample followed on five occasions from early childhood (age 3 years) to middle adolescence (age 14 years). The statistical technique we used, random intercept cross-lagged panel modelling (RI-CLPM), allowed us to estimate, at the within-person level, both within-domain and between-domain longitudinal associations. We expected both, the latter driven primarily by externalising problems and cognitive ability. In particular, we expected that cognitive ability would lower internalising and externalising problems and that externalising problems would impair cognitive skills. We hypothesised that low cognitive ability would be related to increases in externalising behaviour, in line with evidence for the causal role of primarily frontally-mediated deficits in executive functions (e.g., attention, planning, working memory and response inhibition) in a range of externalising behaviours or disorders [Reference Sergeant, Geurts and Oosterlaan20, Reference Van der Meere, Marzocchi and De Meo21]. We expected it to be related to increases in internalising symptoms in view of the role of memory dysfunction and poor language skills in internalising problems [Reference Price and Drevets22, Reference Toren, Sadeh, Wolmer, Eldar, Koren and Weizman23]. We also anticipated that internalising and externalising problems would mutually increase one another in childhood, in line with much previous research showing strong, usually childhood-limited, reciprocal associations between them [Reference Boylan, Georgiades and Szatmari1, Reference Van der Ende, Verhulst and Tiemeier9, Reference Moilanen, Shaw and Maxwell10]. Finally, we expected externalising problems to impair cognitive skills, e.g., by compromising learning [Reference Rajendran, Rindskopf, O’Neill, Marks, Nomura and Halperin24]. RI-CLPM provides the optimal analytic tool to study such longitudinal associations because it combines the advantages of hierarchical (multilevel) modelling with those of cross-lagged panel modelling. Similar to hierarchical modelling it allows for the disaggregation of the between-person (individual differences in scores) from the within-person (longitudinal intra-individual variability) variance components. At the same time, the cross-lagged paths are modelled as in a traditional path analysis within a structural equation modelling framework. By segregating the between-person, “trait-like” aspects of problem behaviour and cognitive ability from the within-person deviations from one’s own overall longitudinal trajectory, the interpretation of the paths reflects associations relative to one’s own typical levels of problem behaviour and cognitive ability, rather than relative to the levels of problem behaviour and cognitive ability of other children [Reference Berry and Willoughby25]. Similar to both hierarchical modelling and cross-lagged panel modelling, RI-CLPM allows for adjustment by time-varying and time-invariant covariates. Our analyses therefore controlled for important child and family covariates - including maternal psychological distress and education, socioeconomic disadvantage, family structure and parenting - associated with both cognitive ability and problem behaviour in children [Reference Choe, Olson and Sameroff26, Reference Huisman, Araya, Lawlor, Ormel, Verhulst and Oldehinkel27].

2. Method

2.1. Sample

We used data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS), a population-based cohort of children born in the UK over 12 months from September 2000 [Reference Joshi and Fitzsimons28]. The children were around 9 months old at Sweep 1, and 3, 5, 7, 11 and 14 years old at Sweeps 2–6, respectively. The sample of MCS was constructed to be, when weighted, representative of the total UK population. A key asset of MCS is that it is stratified with certain sub-groups (strata) of the population being intentionally over-sampled, namely families living in disadvantaged areas, those of ethnic minority backgrounds in England and those in the smaller nations of the UK. The disproportionate representation of these groups ensures that typically hard to reach populations are adequately represented. Eligible families were identified using government data relating to Child Benefit, a benefit with almost universal coverage [Reference Connelly and Platt29]. In total, 19,244 families participated in MCS. Our analytic sample included children (singletons and first-born twins or triplets) with valid data on problem behaviour and cognitive ability in at least one of Sweeps 2 (when they were first measured in MCS) to 6 (90% of total sample size; N = 17,318; 51% male). Ethical approval was gained from NHS Multi-Centre Ethics Committees, and parents (and children after age 11 years) gave informed consent before interviews took place.

2.2. Measures

Internalising and externalising problems. These were assessed with the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) at all ages. The SDQ is a short, psychometrically-valid and widely-used behavioural screening tool [Reference Goodman30]. It includes five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour. In line with recommended practice for community samples [Reference Goodman, Lamping and Ploubidis31], the internalising scale comprises the 10 SDQ items from the emotional and peer problems subscales, and the externalising scale the 10 items from the hyperactivity and conduct problems subscales. Scores on these two scales range 0–20 with higher scores indicating more serious problems or symptoms. In the analytic sample, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the scales was satisfactory across assessments, ranging from 0.61 (internalising at age 3) to 0.81 (externalising at age 11).

Cognitive ability. At each sweep, cognitive ability was derived using the age-adjusted cognitive assessments available. At age 3, these were the Bracken School Readiness Assessment-Revised which measures ‘readiness’ for formal education by evaluating concept development in young children relating to six basic skills (colours, letters, numbers/counting, sizes, comparison, and shapes) [Reference Bracken32], and the second edition of the British Ability Scales (BAS) for Naming Vocabulary which measures expressive language [Reference Elliott, Smith and McCulloch33]. At age 5, these were the BAS tests for Naming Vocabulary, Pattern Construction (measuring spatial problem solving) and Picture Similarities (measuring non-verbal reasoning). At age 7, the tests used were the BAS Pattern Construction test, the BAS Word Reading (measuring educational knowledge of reading) test and the National Foundation for Educational Research Progress in Maths test. At age 11, the BAS Verbal Similarities test assessing verbal reasoning and verbal knowledge was used. Finally, at age 14 the cognitive assessment was a word activity task measuring understanding of the meaning of words. This task, used in other general-population studies in the UK, is based on standardised vocabulary tests devised by the Applied Psychology Unit at the University of Edinburgh in 1976 [Reference Elliott and Shepherd34]. When multiple cognitive assessments were available (i.e., at ages 3, 5 and 7), we measured cognitive ability by using the scores derived from a principal components analysis of these assessments. At each assessment, component scores were then transformed into a standardised score with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 [Reference Hanscombe, Trzaskowski, Haworth, Davis, Dale and Plomin35]. For ages 11 and 14, when only one measure of ability was available in MCS, we transformed the age-adjusted ability score into a standardised cognitive ability score.

Covariates. We controlled for both time-invariant and, where possible, time-varying covariates to minimise confounding. The time-invariant covariates were ethnicity (white, Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi, black, mixed, and other), birth weight (>2.5 kg or not), breastfeeding status and maternal age at birth. At baseline (age 3), we also adjusted for maternal education (university degree or not) and maternal smoking status as well as the following parenting variables, not measured longitudinally in MCS: a) parent-child relationship, using Pianta’s (1992) Child-Parent Relationship Scale [Reference Pianta36]; alpha = 0.77; b) quality of emotional support, using the short form version of the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment scale [Reference Caldwell and Bradley37]; alpha = 0.61, and c) household chaos, assessed using 3 items asking the parent how calm and organised the home atmosphere is (alpha = 0.68). The time-varying covariates were: a) socioeconomic disadvantage, measured using a 4-item summative index [Reference Malmberg and Flouri38] comprising overcrowding, lack of home ownership, receipt of income support, and income poverty (alphas ranged from 0.65 at ages 7 and 11 to 0.69 at age 3); b) maternal psychological distress, assessed with the Kessler K6, a 6-item screener of psychological distress [Reference Kessler, Barker, Colpe, Epstein, Gfroerer and Hiripi39] (alphas ranged from 0.85 at age 3 to 0.89 at age 11); c) harsh parental discipline, measured using the 3 items of the Conflict Tactics Scale that ask the parent whether they smack, tell off or shout at the child when she misbehaves [Reference Straus, Hamby, Kaufman Kantor and Jasinski40] (alphas ranged from 0.66 at ages 3 and 5 to 0.67 at age 7); d) family structure (living with both natural parents or not); e) parental involvement (whether or not the parent reads to or with their child daily or almost daily), and f) child’s irregular bedtimes. The time-varying covariates were measured, if available, until age 11, apart from maternal psychological distress which was also measured at age 14 to account for any influences of mother’s mental health on her perception of her child’s behaviour [Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward41].

2.3. Statistical analysis

The RI-CLPM extends the traditional cross-lagged model by including random intercepts for the repeatedly measured outcomes. Thus, it is essentially a multilevel model and therefore able to distinguish the within-person level variance (the individual’s temporal deviation from their expected score) from the between-person level variance (the individual’s temporal deviation from the sample mean) [Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman42]. Hence the paths of the developmental cascades reflect “pure” longitudinal changes which are not conflated by between children’s differences across the measures over time. Put differently, the RI-CLPM is a cross-lagged structural equation model that examines within-person longitudinal associations within and between states, after controlling for trait levels and prior states.

We parameterised the model as follows. Latent variables were derived for each of the repeated measures (15 latent variables in total) and factor loadings were all constrained to 1. The variances of all observed variables were constrained to 0 allowing the latent variables to capture the within-person variance. Between-person effects were captured by introducing three additional latent variables (one for each of internalising, externalising and cognitive ability) with factor loadings constrained to 1. These random intercepts represent stable trait-like differences between individuals separated from the within-person processes. First, we ran the RI-CPLM without adjustments for confounders. Next, we adjusted the path estimates by regressing the latent variables capturing within-person processes across waves on the time-varying covariates. We also regressed the three random intercepts on the time-invariant covariates. We removed from the analysis covariates with variance inflation factor (VIF) estimates >4 to avoid obtaining biased standard errors due to multicollinearity.

In light of the evidence suggesting that hyperactivity is strongly associated with cognitive ability and shares genetic risk with it [Reference Martin, Hamshere, Stergiakouli, O’donovan and Thapar43] we additionally ran a bias analysis whereby we replicated the adjusted RI-CLPM using only the conduct problems scale of the SDQ to approximate externalising problems. All analyses were stratified by gender in view of the evidence for differences between males and females in the developmental trajectories of both cognitive ability and problem behaviour in childhood [Reference Carter, Godoy, Wagmiller, Veliz, Marakovitz and Briggs-Gowan44–Reference Flouri, Papachristou, Midouhas, Joshi, Ploubidis and Lewis47]. Initially, we ran three models, each with autoregressive, or cross-lagged or both autoregressive and cross-lagged path estimates constrained to be equal for each of internalising problems, externalising problems and cognitive ability. These were then compared to the unconstrained model using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square test [Reference Satorra, Heijmans, Pollock and Satorra48]. Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) [Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen49]. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used throughout to handle the skewed distributions of internalising and externalising problem scores in the analytic sample. Missing data on the outcomes were handled using full information maximum likelihood. The MCS stratum was controlled to account for the disproportionately stratified design of the study. Attrition and non-response were taken into account by using weights. Significance level was set at 0.01 to account for multiple testing. Analyses were performed in Stata SE 14.2 [50] and Mplus 7.4 [Reference Muthén and Muthén51].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

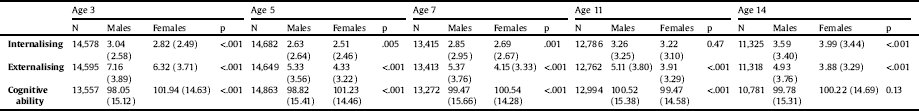

Table 1 shows the mean internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores across genders and assessments. Males had significantly higher internalising and externalising scores and lower cognitive ability scores at ages 3, 5 and 7 years, compared to females. At age 11, females had lower externalising and cognitive ability scores, compared to males, and similar levels of internalising problems. At age 14, the two genders did not differ in cognitive ability but, compared to females, males scored higher in externalising and lower in internalising problems.

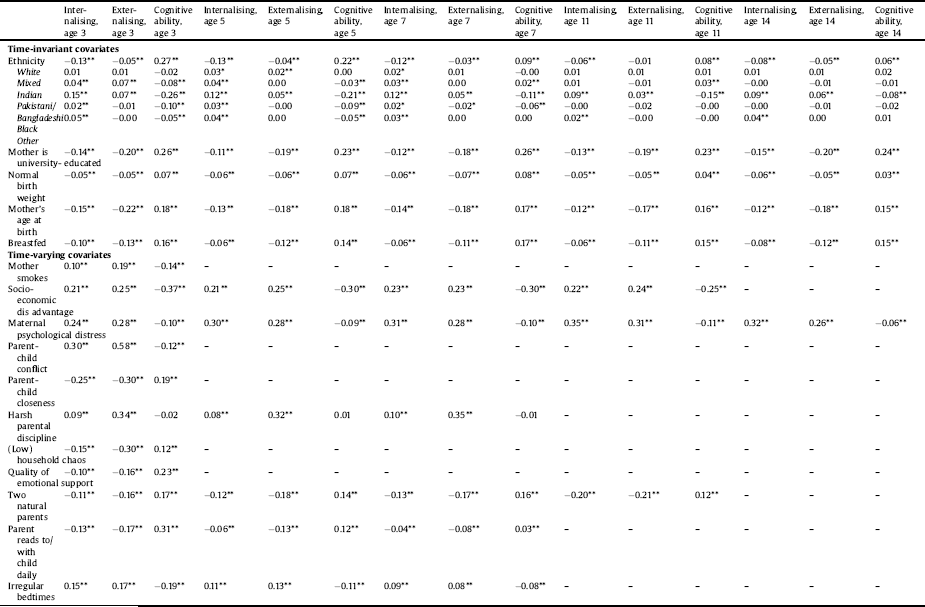

At the bivariate level, there was evidence for both within-domain and between-domain correlations at the five assessments. Internalising and externalising scores were positively associated with each other at all assessments, with correlation coefficients ranging from r = 0.38 at age 3 to r = 0.50 at age 11. Cognitive ability scores were negatively related to both, although much more modestly, with correlations ranging from r=-0.09 (internalising, age 14) to r=-0.31 (externalising, age 7). All associations were highly consistent across genders. Table 2 shows the associations of each of the covariates with internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores. As can be seen, all covariates were associated, in the expected direction, with all three outcomes in at least one assessment point, hence they were all included as confounders in the RI-CLPM.

Table 1 Unweighted means (SD) of internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores at ages.3–14

Table 2 Cross-sectional pairwise Spearman’s correlations of internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores with covariates.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

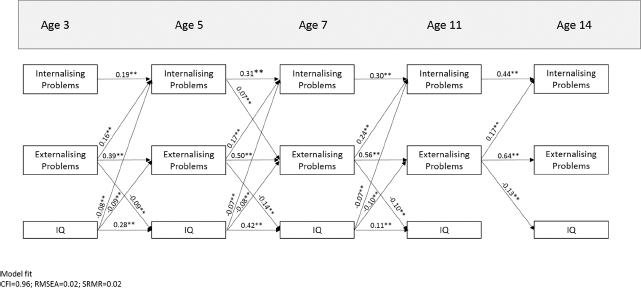

Fig. 1. Statistically significant (p < 0.01) standardised within-person estimates of autoregressive and cross-lagged paths of internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores at ages 3–14 years in males. Covariate effects and within-time correlations are not shown. All variables are latent.

3.2. Developmental cascades

In the first RI-CLPM, the autoregressive and cross-lagged path estimates for each of the three outcomes were restricted to be equal. This model fitted the data poorly (males: CFI = 0.87; SRMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.03; females: CFI = 0.88; SRMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.03). In the second, the cross-lagged paths were restricted to be equal. Fit indices of this model were mostly within the recommended cut-offs (males: CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.02; females: CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.02), suggesting adequate fit to the data. In the third, the autoregressive paths were restricted to be equal. The fit indices of this model were all also close to the recommended cut-offs (males: CFI = 0.94; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.02; females: CFI = 0.94; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.02). These models were then compared to the unrestricted model in which all path estimates were allowed to vary. The unrestricted model showed, as expected, the best fit to the data (males: CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.02; females: CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.02; SRMR = 0.02). The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test for nested models also showed that this model was a better fit to the data compared to the models with equality constraints (all p-values<0.001) suggesting inequality in the magnitude of the cross-lagged and autoregressive paths. Therefore the unrestricted model in which all paths were allowed to be freely estimated was selected for further interpretation. Of all covariates included in the model, only family structure at age 7 and socioeconomic disadvantage at age 5 had VIF values >4 and were therefore subsequently removed.

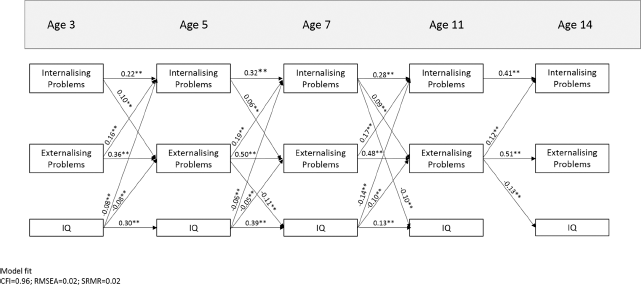

The significant auto-regressive and cross-lagged paths are illustrated in Figs. 1–2. The estimates of the auto-regressive paths suggest within-person associations over time for problem behaviour, especially externalising symptoms, throughout childhood and adolescence in both genders. The estimates of the cross-lagged paths in males (Fig. 1) suggest that internalising problems did not, in general, predict change in either cognitive ability or externalising problems. By contrast, externalising problems were associated with both increases in internalising problems and decreases in cognitive ability throughout both childhood and adolescence. Cognitive ability was associated with lower levels of later internalising and externalising problems across both early and middle childhood but not adolescence. Fig. 2, which shows the paths for females, suggests that internalising problems had (weak) cross-domain effects (especially on externalising problems) in childhood, generally absent in males. As in males, externalising problems were associated with increases in later levels of internalising problems throughout the study period, and cognitive ability with decreases in later levels of both internalising and externalising problems in childhood. By contrast, the bidirectional association between externalising problems and cognitive ability seen in males was not shown here. In both genders, externalising problems had the strongest cross-domain effects.

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

The adjusted RI-CLPM which included only the conduct problems scale of the SDQ as the measure of externalising problems yielded similar results to the model in which externalising problems included both conduct problems and hyperactivity. In males three additional paths emerged as statistically significant. Internalising symptoms at ages 3 and 11 years were significantly associated with increases in conduct problems at the subsequent assessments. Internalising problems at age 5 were additionally related to decreases in cognitive ability at age 7. Finally, the path between conduct problems at age 11 and later cognitive ability was not significant. In females two additional significant cross-lagged paths emerged as statistically significant compared to the original models using the full externalising problems scale. Internalising problems at age 5 and conduct problems at age 7 were associated with lower cognitive ability at ages 7 and 11, respectively.

4. Discussion

In this study of over 17,000 children in the UK, we examined, for the first time, cascading processes among internalising problems, externalising problems and cognitive ability in a general-population sample followed from early childhood (age 3 years) to middle adolescence (age 14 years). By using a novel analytic approach which controlled for the trait-like components of the three constructs, we showed evidence for important longitudinal associations between the three constructs’ state-like elements. Controlling for trait-like components is important because, by definition, these components are stable over time and therefore do not easily fit into notions of causality.

One of this study’s most noteworthy findings was the consistent evidence for cross-construct effects of ‘state-like’ externalising problems in both childhood and adolescence. In childhood, externalising problems were associated with higher levels of later internalising problems in both genders and reduced cognitive ability in males. In adolescence, and in both genders, they were related to increases in internalising scores and decreases in cognitive ability. Another important finding is that cognitive ability also had cross-construct effects, although only in childhood. The cross-construct effects of cognitive ability were weaker than those of externalising problems but nonetheless evident for both internalising and externalising problems and in both genders. The last finding that we think is worth reflecting on is that bidirectional effects appeared to be childhood-limited and gender-specific. In males, the consistent bidirectional association found was between externalising problems and cognitive ability. In females, it was between externalising and internalising problems, although, throughout, the effect of internalising problems was weak, in line with previous findings [Reference Boylan, Georgiades and Szatmari1, Reference Gooren, van Lier, Stegge, Terwogt and Koot2].

Fig. 2. Statistically significant (p < 0.01) standardised within-person estimates of autoregressive and cross-lagged paths of internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores at ages 3–14 years in females. Covariate effects and within-time correlations are not shown. All variables are latent.

The pattern of results observed in our study is unique in terms of suggesting that the majority of cross-domain effects occur in childhood and dissipate in adolescence. Nonetheless, the finding that certain paths, particularly those pertaining to the significant prospective associations between externalising problems and later internalising problems is well documented in previous research [Reference Gooren, van Lier, Stegge, Terwogt and Koot2, Reference Gilliom and Shaw52]. As noted earlier, the failure model posits that externalising problems can lead to conflicts with parents and peers as well as peer rejection (failure in the social domain), in turn leading to depressed mood. Interestingly, these findings of ours were consistent for both males and females, despite the higher levels of externalising problems observed in males at younger ages. Our study also provides further support for the deleterious effect of low cognitive ability on later externalising problems in childhood, consistent with studies showing that lower cognitive ability in childhood is a risk factor for later antisocial behaviour [Reference Koenen, Caspi, Moffitt, Rijsdijk and Taylor54]. The exact causal mechanisms via which low childhood cognitive ability increases the risk for antisocial behaviour are still being investigated, however, beside environmental mediation, it is likely that lower childhood cognitive ability is a marker of neuroanatomical deficits that increase vulnerability to problem behaviours [Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Roberts, Martin, Kubzansky and Harrington53]. Cognitive ability and externalising problems are of course also genetically related. Koenen et al. (2006), for example, demonstrated that, in boys, the relationship between low cognitive ability and antisocial behaviour in early childhood was explained completely by shared genetic factors [Reference Koenen, Caspi, Moffitt, Rijsdijk and Taylor55]. This might also explain why in our study the effect of externalising problems on cognitive ability was detected in males consistently throughout the study period, while in females it did so only intermittently. Finally, in our study the effect of cognitive ability on both types of problems was comparable which is not in line with previous findings showing nonsignificant or small effects of cognitive ability on internalising problems [Reference Flouri, Midouhas and Joshi56].

4.1. Implications

The two-way dynamic association between externalising problems and cognitive ability in childhood has important implications from a public health perspective as it suggests that interventions targeting either cognitive ability or externalising problems in childhood could benefit both, at least in males. The inverse association between cognitive ability and both types of problems in childhood also has important implications as it suggests that improvements in cognitive skills can lead to reductions in externalising and internalising problems in children. Together, these findings suggest that, in either childhood or adolescence, reducing behavioural problems could have both emotional and cognitive benefits. In childhood, improving cognitive skills could reduce both emotional and behavioural problems.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths including the large and population-based sample, the length of the study period spanning important transitions in childhood (such as the transition to school, puberty and secondary school) and the use of an analytic technique that allowed us to model ‘pure’ intra-individual longitudinal associations within and between states after controlling for trait levels and prior states. The latter point is of particular importance considering that this is the first study to use this approach to describe the prospective associations between problem behaviour and cognitive ability. However, it also has five important limitations. First, internalising and externalising problems were parent (overwhelmingly mother) reported, with no triangulation from other reporters such as teacher or child. This may be particularly problematic for internalising problems in view of the evidence for higher levels of agreement between parent and self reports on the SDQ for externalising than for internalising disorders [Reference Van der Meer, Dixon and Rose57]. Second, cognitive ability was measured differently across assessments. Although to some extent this was necessary given the developmental stage of our sample, on two occasions (ages 11 and 14) we had to use single ability measures. Future studies using data on several domains of cognitive function would be needed to establish the robustness of our findings. Third, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed associations are driven, at least partly, by unmeasured common causes. The associations we observed may be due to shared genetic influence, for example. There is evidence, for example, that some of the genetic influence affecting internalising problems in adolescence is already expressed as externalising problems in childhood, with academic difficulties accounting for a portion of their phenotypic association. Together, these findings suggest the possibility that academic difficulties contribute to the development of internalising problems via gene-environment interplay [Reference Wertz, Zavos, Matthews, Harvey, Hunt and Pariante58]. Nonetheless, genetic confounding would need to have a complex effect on the three outcomes we considered in order to produce the observed variability in associations. Fourth, time intervals are not explicitly modelled in RI-CLPM, and so there may be bias introduced by the use of unequal time intervals between assessments. Finally, our last follow-up, in middle adolescence, is the peak period for the emergence of internalising problems and the more serious externalising behaviours [Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar‐Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustun59]. Future studies with follow-ups in late adolescence would be useful in testing and extending our findings about the nature of the association between internalising, externalising and cognitive ability scores across the second decade of life.

5. Conclusions

In this study we examined cascading processes among emotional (internalising) problems, behavioural (externalising) problems and cognitive ability in a large general-population sample followed from early childhood to middle adolescence. We found strong evidence for cross-domain effects especially for externalising problems throughout and for cognitive ability in childhood. Bidirectional associations were gender-specific, although involving externalising problems in both genders, and childhood-limited. The cross-domain associations found suggest that improvements in cognitive skills could lead to reductions in emotional and behavioural problems in childhood, whereas reductions in behavioural problems in either childhood or adolescence could have both emotional and cognitive benefits.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/N007921/1].

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.