Introduction

In numerous situations, psychiatrists have captured the public spotlight, with experts offering prospective opinions about the mental health of famous figures from second-hand observations [Reference Appelbaum1, Reference McLoughlin2]. In the United States, such activities are explicitly prohibited by the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) so-called Goldwater Rule for its members [Reference McLoughlin2]. Still in-force today [3], the Goldwater Rule was introduced following a provocative Fact magazine feature in 1964 that collated psychiatric views on Senator Barry Goldwater (a United States presidential candidate) [Reference McLoughlin2]. After subsequently losing the election, Senator Goldwater initiated a successful libel suit against this publication before the APA instituted this eponymous regulation 50 years ago in 1973. Specifically, the APA’s Goldwater Rule states:

On occasion psychiatrists are asked for an opinion about an individual who is in the light of public attention or who has disclosed information about himself/herself through public media. In such circumstances, a psychiatrist may share with the public his or her expertise about psychiatric issues in general. However, it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement. [3].

Debates about the applicability of the Goldwater Rule have become increasingly pertinent since the policy was first adopted. Significantly, Kroll and Pouncey highlight how politicians are frequently the subject of psychological and behavioral questions, which can have broader implications and societal importance [Reference Kroll and Pouncey4]. For instance, during the 1970s, Senator Thomas Eagleton withdrew his nomination as a US vice-presidential running mate when it became known that he had received psychiatric treatment [Reference Soreff and Bazemore5]. In 1988, conjecture in the US media circulated around the mental health of the Democratic presidential nominee, Michael Dukakis, who subsequently released his medical records [Reference Rosenthal6]. More recently, Donald Trump’s presidential term intensified public speculation about his mental health and exchanges specifically concerning the Goldwater Rule. In this period, psychiatrists openly ruminated on Trump’s behavioral and personality traits, arguing that such issues deserved greater scrutiny [Reference Lee7, Reference Friedman8]. Other contemporary events have elicited similar mental health suppositions about European politicians [Reference Plante9–11]. The introduction of social media and alternative communication platforms is adding to the complexities around this regulation [Reference McLoughlin2].

Nevertheless, the Goldwater Rule affects more than just psychiatry’s intersections with the political domain. A prominent example of this was public diagnostic assessments following the Germanwings plane crash in 2015 [e.g., Reference Healy12]. Another instance occurred during the Johnny Depp v. Amber Heard trial in 2022, which also provoked conversations about forensic-psychiatric ethics [Reference Hatters Friedman, Sorrentino and Rosenbaum13]. During these proceedings, the psychiatrist appointed by Heard’s legal team proffered opinions on Depp’s mental health without a clinical interview, and thus, questions arose about their adherence to the Goldwater Rule [Reference Hatters Friedman, Sorrentino and Rosenbaum13]. Additional famous figures who have been the subject of mental health conjecture without examination or consent include the actor, Robin Williams, the singer, Britney Spears, and the Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle [Reference Davis14, 15].

Proponents of the Goldwater Rule attest that speculative psychiatric opinions can be stigmatizing [Reference Brendel16] and even discriminatory [Reference Davis14]. For Appelbaum, “real harm to real people constitutes a reason beyond professional embarrassment for psychiatrists to avoid judgments on the basis of information gleaned from the media” [Reference Appelbaum1]. Further, together with individualized hazards, commenting on the mental health status of a person without direct assessment or their consent could be harmful to the reputation of psychiatry [Reference Appelbaum1], perpetuating anachronistic views around mental illness [Reference Brendel16]. In the political domain, there have been suggestions that pathologizing the actions of national leaders can detract from legitimate conversations about rational abuses of power [Reference House17]. Accordingly, due to these arguments, the Goldwater Rule has been depicted as an essential component of professional standards and integrity within the psychiatric field [Reference Redinger, Gibb and Longstreet18].

Conversely, specialists have foregrounded what they consider to be the medical “duty to warn”, emphasizing an expert’s obligation to safeguard civil society and inform the public about potential risks [Reference Gartner, Langford and O’Brien19]. Kroll and Pouncey reason similarly, affirming that psychiatrists are duty-bound to communicate professional concerns about prominent figures, albeit risking reputational damage to the discipline [Reference Kroll and Pouncey4]. The Goldwater Rule has been criticized as theoretically impinging upon a psychiatrist’s right to free speech [Reference Appel20], although some researchers disagree with this contention [Reference Andrade and Redondo21]. Notably, an academic was reportedly sacked by their university for expressing opinions about the mental health of Trump and his supporters, despite claiming this violated free speech rights and a professional obligation to warn the public [Reference Reyes22]. Equally, Lee and Glass [Reference Lee and Glass23] depict the APA’s position as overly restrictive, underlining how different medical professions are not subject to the same ethical rules and can thus offer health commentary on public figures.

As an APA policy, the Goldwater Rule has naturally garnered substantial scholarly and popular attention in the United States. Although psychiatrists have examined the Goldwater Rule during cases in different countries, like for an Indian actress [Reference Singh24] and a South Korean politician [Reference Lee25], there is a limited academic discussion about its applicability outside of the United States. As 2023 marks the fiftieth year of the introduction of the APA’s regulation, we were interested in its current relevance in Europe. Consequently, we sought to examine whether European associations had similar guidelines to the Goldwater Rule or comparable ethical positions around psychiatrists offering media or public commentary on individual psychopathology.

Methods

To gather an impression of European contemplations regarding issues addressed by the Goldwater Rule and whether similar regulations to the APA’s rubric existed around public commentary by psychiatrists, we focused on the National Psychiatric Association Members (NPAs) of the European Psychiatric Association [26]. Founded in 1983, the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), is the main body representing psychiatry in Europe, emphasizing the improvement of care and the development of professional excellence [26]. The EPA encompasses 44 NPAs from 40 countries who represent more than 80,000 psychiatrists across Europe [27].

Between 24th May and 16th December 2022, we searched NPA websites displayed by the EPA [27] to gain information on whether each association has regulations that are analogous to the Goldwater Rule or specifically relate to public or media mental health commentary. Where information was not definitively available or online materials were in languages other than English, we initiated e-mail communication to addresses obtained from NPA websites or to those individuals in management or board positions (e.g., Presidents, Secretaries, Chairpersons, etc.). Correspondence was sent in English and NPAs were informed that this was a research project around the Goldwater Rule. NPAs were asked to indicate whether they have an ethical rubric around media commentary or comparable guidelines forbidding psychiatrists from providing opinions without consent on the mental health status of people they have not treated.

NPAs who did not respond to initial mailings were sent reminder emails. Subsequently, we tried to reach those NPAs who had not responded to our emails by phone, using numbers obtained from NPA websites. Following these rounds of communication, we additionally followed up on outstanding responses using the mediation of research partners in respective countries. Throughout the data-gathering process, providing information was voluntary and no compensation was offered to NPAs for responding. Having collated answers from the NPAs, two authors interpreted the responses and coded them into four categories: “NPA-level rules or position,” “No NPA-level rule or position but noted country-level rule,” “No NPA-level rules or position and did not note country-level rules,” and “No response.”

Results

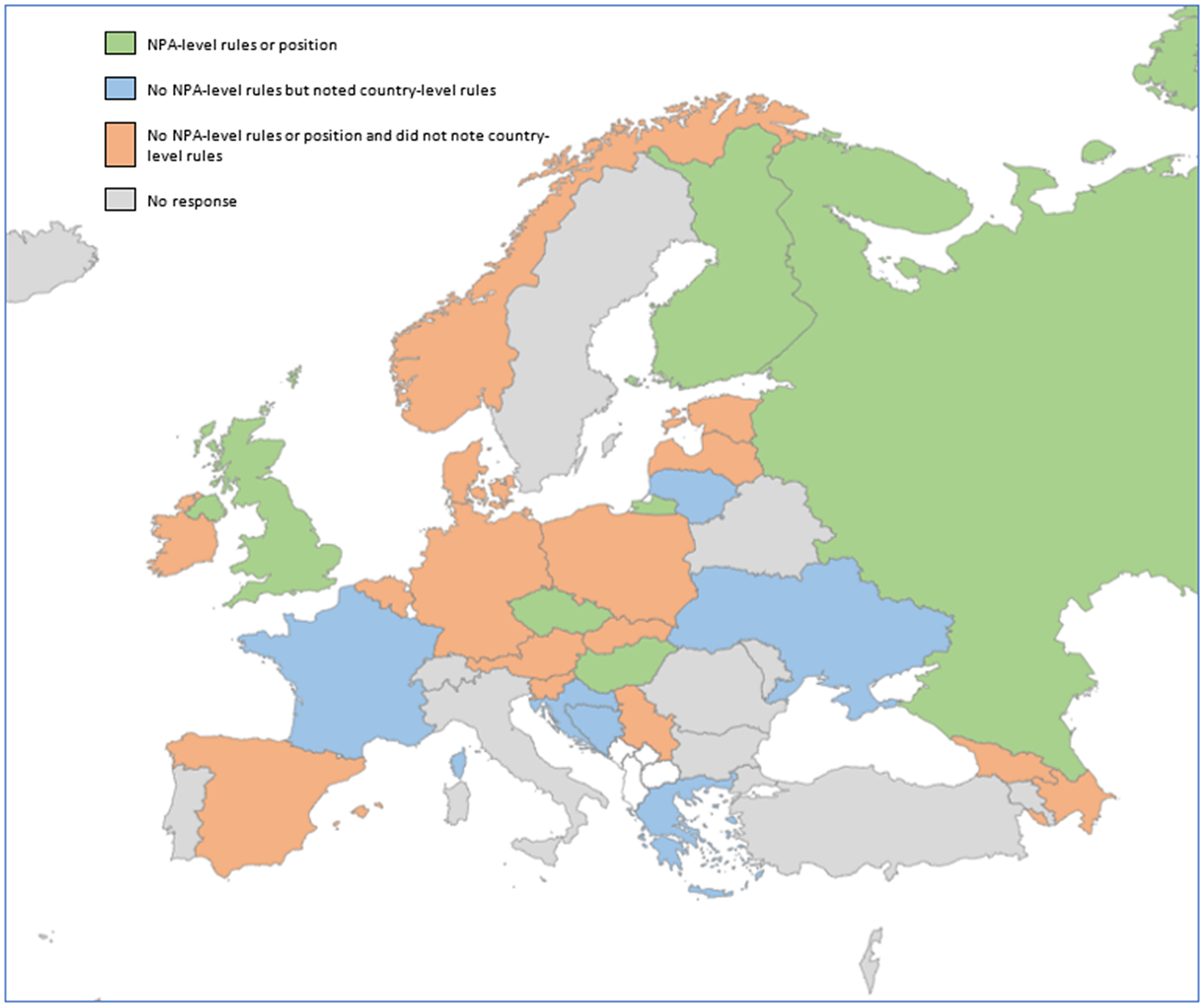

Following our data-gathering process, 27 NPAs of the 44 NPAs either provided responses or exhibited materials on their website (61.3% of the total number of NPAs). Of the total 44 NPAs, 16 NPAs did not exhibit relevant materials on their website or respond to our correspondence (38.7% of the total number of NPAs). Included in these 16, 1 NPA asked for a financial contribution for information and therefore was categorized as not providing a response. Per our interpretations and classifications, the positions of 27 NPAs are summarized below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of European NPAs and their responses per our interpretation and categorization.

NPA-level rules or position

From NPA respondents or those with relevant web resources, six NPAs had apparent rules or indicated positions around media and public commentary for their members. The Royal College of Psychiatrists in the United Kingdom explicitly supports the Goldwater Rule [28]. The Finnish Psychiatric Association had a comparable stance, forbidding conjectural opinions about a person’s psychopathology [29]. The Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia largely considers speculative comments regarding an individual’s mental health to be irresponsible without a first-hand assessment or underlying data, and instead adheres to an individual approach for each case. The Polish Psychiatric Association stated that they were in favor of the Goldwater Rule and call for non-discriminatory discourse around individuals with mental illness. The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland does not comment on individuals in the media and recommends that their members do the same. Other organizations like the Hungarian Psychiatric Association [30] and the Czech Psychiatric Association [31], maintain broad ethical positions around respect and confidentiality on the subject of public commentary.

No NPA-level rule or position but noted country-level rule

Rather than NPA-level rules, six NPAs included in our study highlighted specific national laws dedicated to this topic; for the avoidance of doubt, it should be noted that this category does not necessarily include only those countries that do have applicable legislation, but rather where these were expressly emphasized by NPAs. For instance, in Greece, psychiatrists “must ensure that the mentally ill persons are presented to the media in a way that protects their honor and dignity and at the same time reduces the stigma and discrimination against them. The psychiatrist should not make announcements to the media about the alleged psychopathology of any individual” [32]. Furthermore, in Ukraine, “it is prohibited to determine the state of mental health of a person and establish the diagnosis of mental disorders without a psychiatric examination of the person” [33] and there are regulations around upholding patient confidentiality [34]. The Association of Psychiatrists in Bosnia and Herzegovina reported that protocols incorporating the Goldwater Rule were included within the 2019 national ethical guidelines report on mental health.

In Lithuania, discussing any health data that is considered to be confidential is forbidden by law [e.g., 35]. The French Federation of Psychiatry underlined a general rule for all physicians forbidding a diagnosis when one has not received the patient and the sharing of confidential information outside of medical reasons benefitting the patient. The Croatian Psychiatric Association has no guidelines for public appearances in the media by its members. However, they noted that there are employer recommendations for doctors who appear in the media, which typically recommend talking about disorders in general and not specific cases.

No NPA-level rules or position and did not note country-level rules

15 NPAs included in our results affirmed that they did not have written protocols around media commentary for their members and did not explicitly specify that country-level rules existed. Nevertheless, of these 15, 2 NPAs indicated that they would be open to considering such guidelines at an EPA level. In certain settings, there has been wider theoretical discourse from NPAs around this issue. The Slovenian Psychiatric Association suggested that by professional convention, it would generally be deemed unethical for a psychiatrist to provide commentary on public figures. Moreover, although they do not have an official regulation, the Norwegian Psychiatric Association stated that they had written about the ethical implications of commentary in relation to coverage about Anders Brevik who was convicted of terrorist offenses [Reference Reitan and Lien36].

Discussion

The current status of the Goldwater rule in Europe

The results of our study illustrate that there are no definitive Europe-wide or homogenous guidelines forbidding psychiatrists from publicly commenting on the mental health status of people they have not treated and where they lack consent to do so; positions from the 27 NPAs included in our results ranged from explicit support for the Goldwater Rule to non-existent ethical regulations around media and public psychiatric commentary. This suggests that a sizeable proportion of NPAs in this study had not yet formally addressed the subject. The heterogeneity of these perspectives may be expected given Europe encompasses disparate nationalities and cultures. Additionally, unlike the APA in the United States, there is not one regulatory psychiatric membership body in Europe. Although the EPA serves as an umbrella organization for divergent geographical areas, individual NPAs still retain autonomy about decisions that affect their localized membership [27].

For those NPAs without rules, it may be that discussion about the mental health of public figures is not as prominent, or that psychiatrists feel bound by general ethical conventions, like the Slovenian Psychiatric Association highlighted. From a legislative standpoint, certain countries have developed general regulations around patient confidentiality and medical records, which may impinge upon public and press interactions for psychiatrists. Our research only captures those NPAs who specifically indicated a country-level rule existed and thus there will likely be more apposite laws, mainly for European Union member-states with supra-national legislative frameworks. Yet, it is noteworthy that certain national laws exist dedicated to psychiatrists’ relations with the press, notably Greece that disallows any comments about “alleged psychopathology” in the media [32].

As recent controversial discussions on the mental health of politicians and celebrities demonstrate, the Goldwater Rule still retains a sociocultural and professional resonance 50 years after its introduction [Reference Davis37]. Nevertheless, instances of public or media speculation about an individual’s psychopathology extend beyond the United States. For instance, analogous discourse was evident after the Germanwings crash in 2015, provoking a statement by the German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology [38], which was latterly endorsed by the EPA [39]. More formally, in the authors’ opinion, it may be beneficial for the EPA to consider developing initiatives around this issue and determining whether recommendations concerning media commentary are necessary for a European context, especially given the diverse nature of our responses.

Previous EPA Guidance Papers in distinct psychiatric domains have had a significant political impact [40] and the mission statement of the Council of NPAs aims to improve “psychiatry and mental health care throughout the continent” [26]. Moreover, another international representative organization, the World Psychiatric Association, has recently embedded a statement about media interactions into its Code of Ethics (Principle 5.3) that were established in 2020, namely that psychiatrists should: “offer accurate information to the media to educate the public about the nature and consequences of psychiatric disorders and their treatment, and to dispel misconceptions about people with psychiatric disorders” [41]. Consequently, an official EPA project focusing on the ethics of media commentary may involve a detailed analysis of NPAs and a more systematic methodology and survey design than we adopted, which could better incorporate national traditions and sociocultural nuances.

Goldwater turns 50: Towards discussions about an adapted European initiative?

Given it was inaugurated in 1973, the Goldwater Rule inevitably reflects professional standards of the time. Thus, the possibility of creating an evolved framework tailored to European conditions and current standards raises obvious questions about how modern practices can be applied to public or media psychiatric commentary in 2023. Consistent approaches influenced by the APA’s guidelines could prevent cross-continent inconsistencies and protect the privacy of individuals who become the focus of public interest in Europe. To that end, the Goldwater Rule has been praised as reducing the dissemination of stigmatizing notions of mental illness [Reference Brendel16], which remains a predominant concern in contemporary psychiatric research and practice [Reference Bhugra, Tribe and Poulter42]. Equally, the APA’s policy can prevent inadvertent harm to individuals with or without mental health conditions [Reference Appelbaum1]. Additionally, findings suggest that psychiatrists may provide commentary in the media for adverse motives, including to draw attention to their own work or for financial gain [Reference Liebrenz43]. Taken together, there are inherent components of the Goldwater Rule that remain pertinent to the current psychiatric discipline [Reference Redinger, Gibb and Longstreet18]. Designed to uphold professional integrity, we believe that the APA’s regulation provides an ethical starting point for sensitive and respectful discourse around mental health [Reference McLoughlin2].

Nonetheless, as others propose, there are justifiable criticisms of the APA’s position, including its inflexibility regarding the medical “duty to warn” [Reference Gartner, Langford and O’Brien19]. This is particularly important since the Goldwater Rule was established in a democratic society and its applicability in oppressive political conditions remains undetermined (and to an extent, untested [Reference Smith, Bhugra, Van Voren and Liebrenz44]). Further, in the discussion around the Goldwater Rule, there are no indications of how psychiatric associations might protect their members who speak out against authoritarian regimes and then face governmental sanctions, like losing their license to practice. Significantly, amidst repressive conditions, there have been occasions where psychiatrists have provided diagnostic opinions without examining a patient, in turn shining a light on abuses and helping to liberate people from detention-based settings [45]. Currently, it could be argued that the Goldwater Rule necessitates a two-tiered approach for public and media commentary; owing to these ethical regulations, psychiatrists with mental health knowledge are not able to provide informed opinions about individual psychopathology but those without specialist training are.

Accordingly, Blotcky and colleagues offer a useful series of vignettes and modifications to the Goldwater Rule [Reference Blotcky, Pies and Moffic46]. Stopping short of a public diagnostic opinion, these include allowing psychiatrists to comment on hypothetical and historical cases, and on openly observable behaviors, which could enable mental health specialists to responsibly inform societal dialogues [Reference Blotcky, Pies and Moffic46]. Although there is the potential for advancing unhelpful conjecture, especially in hypothetical instances, Blotcky et al.’s suggestions could ensure that psychiatric insights are not excluded from critical debates. This may also help support the free speech argument that has previously been identified as a flaw in the APA’s guidelines [Reference Appel20], alongside increasing transparency about the behavior of figures in the public eye.

Another drawback of the Goldwater Rule is that it does not encompass modern communication mechanisms, including social media. As society increasingly consumes its news through sites like Twitter and greater numbers of psychiatrists engage in online networks [Reference Koh, Cattell, Cochran, Krasner, Langheim and Sasso47], concerns arise about how expert opinions can be constructed or interpreted on these platforms [Reference McLoughlin2, Reference Appel20]. Here, again, considerations about position statements on public or media commentary for psychiatrists would need to account for these contemporaneous communication platforms; should social media be treated similarly to news outlets and if not, is it appropriate to develop separate ethical guidelines around these networks? Researchers have noted additional drawbacks to the APA’s current ethical framework, including that it lacks a robust enforcement procedure [Reference Appel and Michels-Gualtieri48]. This latter issue might also need to be critically appraised during any initiatives to investigate the feasibility of European approaches.

Ultimately, should a wider feedback-gathering process be initiated by the EPA amongst European psychiatrists, it may follow that the majority believe that no regulations need to be introduced; this is conceivable based on the heterogenous responses in our results. Notably, specialists have continually speculated on the mental health of public figures, despite an APA guideline being in place [Reference Davis14]. Likewise, the Goldwater Rule may be more pertinent in a US context due to its inherent sociocultural paradigms and traditions. For example, polarization within the American political landscape may enable the exploitation of psychiatric opinions, possibly undermining the profession’s credibility [Reference Knoll49]. Additionally, press coverage in the US can contain sensationalist depictions, focusing on public figures’ personal lives, which could amplify the impact of psychiatric commentary [50]. Here, the litigious reputation of the US judicial system may also increase defamation risks for mental health professionals or publications; significantly, as we have highlighted, Senator Goldwater pursued legal action against Fact Magazine prior to the introduction of the APA’s rule [Reference McLoughlin2].

Although certain European societies will share these paradigms to a greater or lesser extent, sizeable national and sociocultural nuances exist between countries, which could negate the need for a uniform policy. Nonetheless, patterns of polarization may be increasingly affecting European societal discourse [Reference Casal Bértoa and Rama51], thereby rendering a discussion about issues addressed by the Goldwater Rule and the ethics of psychiatric commentary more relevant. Consequently, we believe that collating extensive perspectives on this topic can only serve to bolster the debate, exploring the ethical complexities around providing psychiatric opinions without formal diagnosis or consent.

Limitations and future research directions

Although our study examines various insights from 27 European NPAs on the Goldwater Rule and public and media commentary by psychiatrists, it does have several limitations. Our research did not involve the recruitment of any individuals given all of the NPAs are pre-defined by the EPA [27], and we therefore deemed email and phone communication to the NPAs to be suitable. This entailed a non-systematic approach as information was not always available, which we acknowledge could have affected our response rate. As the NPAs represent 40 countries, it may also follow that there are European psychiatric organizations that are not included in the EPA’s NPAs who could make valuable contributions to this discussion. However, in the authors’ view, we deemed our methodology to be suitable for gaining perspectives on this topic from a broad subsection of European countries. Our study yielded an inclusion rate of 61.3% of total NPAs (27/44 NPAs). Although this meant that the results do not incorporate the views of certain NPAs, we deemed this to be sufficiently robust for a preliminary European-wide analysis on this topic; notably, our inclusion rate of 61.3% is higher than average participation rates for surveys found elsewhere in the scientific literature [e.g., Reference Wu, Zhao and Fils-Aime52, Reference Fincham53].

It is possible that NPA representatives did not have full knowledge about historical organizational positions and therefore applicable rubrics may not have been highlighted in this correspondence. Furthermore, 17 NPAs out of 44 NPAs did not display relevant materials on their website or did not reply. Gathering data via email and phone may have meant that we could not reach certain NPA representatives; for example, the phone number for nine NPAs was not publicly available on their website or was invalid. We did not offer any incentives for replying to our enquiries and one NPA asked for monetary contributions to provide further information, which prevented them from being included in our analysis. Rather than society-level rules, several NPAs did point towards specific national laws, particularly around privacy and confidentiality of individual medical records. Yet, it should be noted that this category does not necessarily include only those countries that do have apposite legislation, but rather where these were expressly emphasized by NPAs.

Finally, our methodology was conducted as an independent research project using English language correspondence and without prior contact with NPAs to uphold the clarity of our enquiries and for ease of analysis. We recognize that English is not the first language for many of the NPAs and therefore it is possible that respondents could have misunderstood the aims of our project, inadvertently provided incorrect information, or may not have replied due to this consideration [Reference Sha and Gabel54]. To improve the participation rate, future projects could be conducted using the native language of individual NPAs. For NPAs who did reply, two authors interpreted the responses and coded them to the four categories displayed in the results. As a common limitation in qualitative research [Reference Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pedersen55], this may raise concerns about reproducibility and could mean some positions or statements were misinterpreted during this stage. Nevertheless, given the heterogeneity of the responses, we deemed this to be a suitable process to concisely summarize our findings, which provide several pertinent insights into the rules and positions around public or media commentary in Europe.

To encompass more comprehensive and holistic reflections, prospective research could focus on NPAs who did not respond or search other applicable European legislation; this could be integrated into any formal EPA schemes, alongside a more systematic survey-based methodologies or innovative study designs. In this regard, as one possible initiative, NPAs could be given a vignette about a psychiatrist commenting on a public figure without their consent. Subsequently, NPAs could be asked to provide their perspectives on this case example drawing upon applicable NPA-level regulations and legal, national, and cultural considerations, which could allow for more homogenous responses. Moreover, other projects could incorporate global outlooks, exploring the viewpoints of psychiatric association outside of Europe and the United States.

Conclusion

We investigated the 44 NPAs of the EPA for their regulations and positions regarding issues addressed by the Goldwater Rule and the ethics of psychiatrists discussing the mental health of individuals publicly or in the media. Our findings demonstrate that a sizeable proportion of NPAs included in our study had not yet explicitly addressed this topic. A detailed EPA initiative may be warranted to explore this issue in greater depth. Ultimately, there might be benefits to establishing institutional frameworks within Europe around psychiatric commentary and expert opinions. This may help to protect individual privacy rights and alleviate notions of stigma. Yet, in the authors’ opinion, such proposals must be tailored to modern psychiatric standards and societal concerns, 50 years after the Goldwater Rule was first put into effect.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to those NPAs who engaged with our enquiries and to international colleagues who helped us with this project.

Author contribution

Conceptualisation: AS, SH, MvW, KS, PF, ML; Investigation: AS, SH. Methodology: AS, SH, ML; Formal Analysis: AS, SH, MvW; Writing – original draft: AS, SH; Writing – review and editing: AS, SH, MvW, KS, PF, ML

Financial support

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Competing interest

Peter Falkai is the current President of the European Psychiatric Association. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.