1. Introduction

The design of psychiatric facilities has always reflected dominant social views about mental illness. The de-institutionalisation of services in the 1960s has shifted the purpose of psychiatric treatment from containment to recovery, thus proposing the transition from traditional hospital-based care to care focused on supporting and maintaining patients within their homes and communities [1]. Within this shift, psychiatric in-patient services should have abandoned the culture of paternalism and embraced the new way of working which allows patients to make informed decisions about their care and treatment, in partnership with their health and social care practitioners. One of the tasks of psychiatric treatment should be to create a safe environment for people to try out positive social interactions (e.g. sharing, peer support, and positive feedback) [Reference Tyson, Lambert and Beattie2]. However, psychiatric facilities are still criticised for being designed as custodial and repressive [Reference Plantamura, Capolongo and Oberti3, Reference Chrysikou4]. Patients treated in psychiatric facilities have repeatedly complained of experiencing negative interactions (e.g. violence), boredom, and of a lack of meaningful interactions with peers, staff and family members [Reference Donald, Duff, Lee, Kroschel and Kulkarni5–Reference Thomas, Shattell and Martin8].

Increasingly, the architecture of psychiatric facilities, including the internal and external environments has been shown to influence the way in which healthcare is delivered. The healthcare delivery is also influenced by other factors such as cultural attitudes and assumptions of the wider society within which the facility is located as well as staff attitudes to the management of psychiatric patients. The term ‘therapeutic milieu’ has been used to describe the physical, social, and cultural context of providing psychiatric care in a holistic manner that supports positive health outcomes [Reference Thomas, Shattell and Martin8]. Just as psychiatry has moved toward an evidence-based approach, so too should the design of psychiatric facilities be informed by the best available evidence in order to demonstrate improvements in clinical outcomes, economic performance, and users’ satisfaction [Reference Ulrich9–Reference Ulrich, Zimring, Zhu, DuBose, Seo and Choi11]. However, the link between psychiatric facilities and clinical outcomes of patients can be very complex. A model is therefore required to search and understand the evidence. The theoretical framework for this study is based on Ulrich's theory of supportive design [Reference Ulrich12]. According to this theory, the hospital environment will reduce stress in patients if it provides opportunities for social interaction, fosters patients’ perceptions of control and autonomy, and creates positive distractions. With regard to social interaction, both the receipt and provision of social support have been found to have beneficial effects. For example, family presence in healthcare settings or genuine peer support is believed to enhance health outcomes and the patient experience. There is strong evidence from early studies conducted during 1970s and 1980s that levels of social interaction can be increased—and presumably beneficial social support as well—by providing communal areas with comfortable movable furniture arranged in small flexible groupings. These studies have largely been conducted in psychiatric units and nursing homes [Reference Ulrich, Zimring, Zhu, DuBose, Seo and Choi11]. In this review we wanted to further explore more recent literature in this field. One may assume that buildings can foster or hinder relevant interactions between users which may then influence outcomes, so that positive social interaction can be taken as a key behavioural criterion to assess the role of architecture. We therefore conducted a systematic review of the existing evidence on the relationship between design and social interactions between different users of psychiatric facilities. Since such evidence cannot always be based on randomised-controlled trials, a wider approach with a narrative synthesis has been taken. We used ‘psychiatric facility’ as a general term for psychiatric in-patient facilities and residential community facilities used by psychiatric patients.

2. Methods

The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and DG13]. The protocol was published on PROSPERO on 1 June 2015 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=22074). Six electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science) were searched from their inception to December 2018. The search words included ‘psychiatric hospitals’ [MeSH], ‘psychiatric ward’, ‘psychiatric facility’, ‘built environment’ [MeSH], ‘architecture’ [MeSH], ‘design’, ‘social interaction’, ‘interpersonal relationships’[MeSH], and ‘social support’. The reference lists of all included articles were hand searched for potentially relevant articles.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if a) conducted in psychiatric facilities with adults (age 18–65), b) reported at least one measure/description of design, and c) reported at least one measure of social interactions. No restriction was placed on location, language, or year of publication. The measures of design were related to urban planning and architecture (e.g. site/location and relatively permanent characteristics such as spatial layout of a hospital, room size, window placement), interior design (e.g. less permanent elements such as furnishings, colours, artwork), and ambient features (e.g. lightning, noise levels, temperature, and odours) [Reference Harris, McBride, Ross and Curtis14]. Social interaction was defined as a process whereby people engage one another in mutually responsive ways. Because the terminology is inconsistent, we used the following descriptors: social interaction, social support, communication, social relationships, personal relationships, social capital, and family support. Studies that reported on structural (frequency or size) and/or functional (quality) dimensions of social interaction were included. We included studies reporting on positive (e.g. staff-patient conversations) and/or negative interactions (e.g. violent incidents).

2.2. Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

All potential studies were exported into reference management software. After removing duplicates, the first author (NJ) screened all titles and abstracts while the other author (JC) screened a random selection of 20% of titles and abstracts to ensure the consistency. If there was any ambiguity on the eligibility of the study, the full paper was reviewed between the two authors (NJ and JC). Inter-reviewer agreement was 90%. The full text of articles meeting the criteria were obtained and reviewed. Reasons for exclusion were recorded. Data extraction was completed independently by two reviewers (NJ and JC). Data were extracted on study methodology, patient characteristics, design characteristics, and social interaction. Study quality was assessed using The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [15] and the RATS for qualitative studies [Reference Clark16]. The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies leads to an overall methodological rating of strong, moderate, or weak in eight sections: selection bias; study design; confounders; blinding; data collection methods; withdrawals and dropouts; intervention integrity; and analysis. The RATS has been used to assess four key areas such as relevance of study question; appropriateness of qualitative method; transparency of procedures; and soundness of interpretive approach.

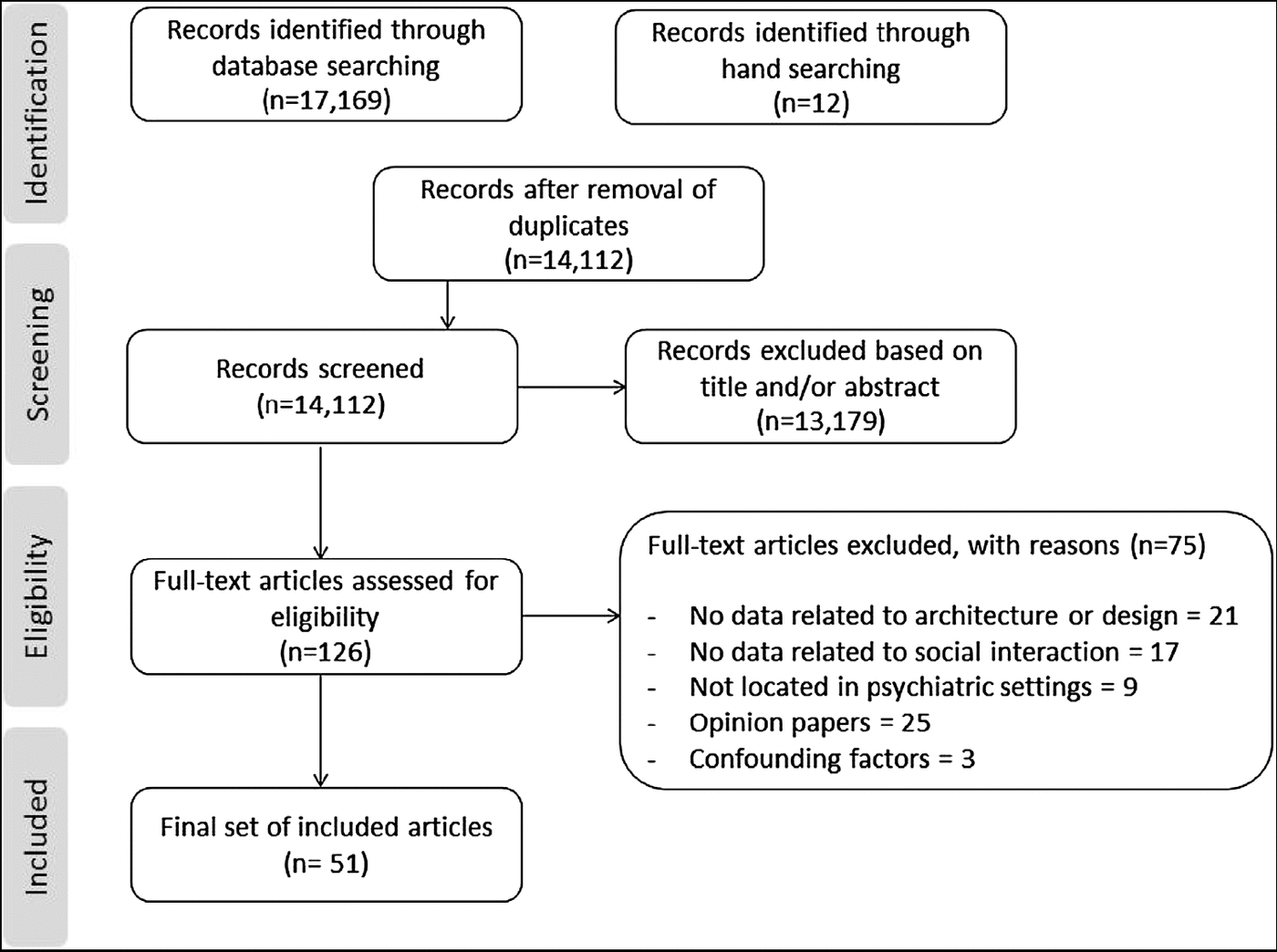

Fig 1. Theoretical framework.

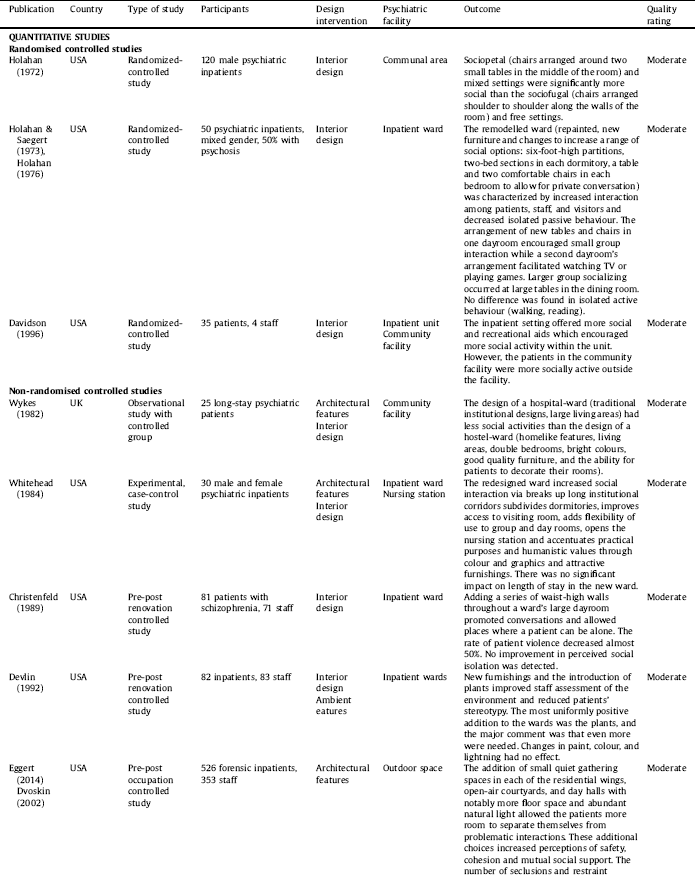

Fig 2. Study selection.

2.3. Data analysis

Narrative synthesis was used to analyse the data, which included four components: theory development, preliminary synthesis, exploring relationships within and between studies, and assessing robustness of synthesis [Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers17]. These elements were undertaken sequentially in an iterative process throughout the review cycle. The theoretical framework includes design interventions (urban planning/architectural/interior design/ambient features) applied at different levels (e.g. from choosing the right building location to designing interior and exterior spaces) in order to create a functional and socially supportive facility [Reference Ulrich12, Reference Harris, McBride, Ross and Curtis14, Reference Fornara and Andrade18, Reference Evans19]. Please see Fig. 1.

Tabulation and grouping data were used to create a preliminary synthesis of how the hospital design encourages social interactions between patients, staff, and visitors. The initial synthesis was largely based on data from randomised-controlled and case-controlled studies. The synthesis was shared among the study authors for discussion and refinement [Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers17].

3. Results

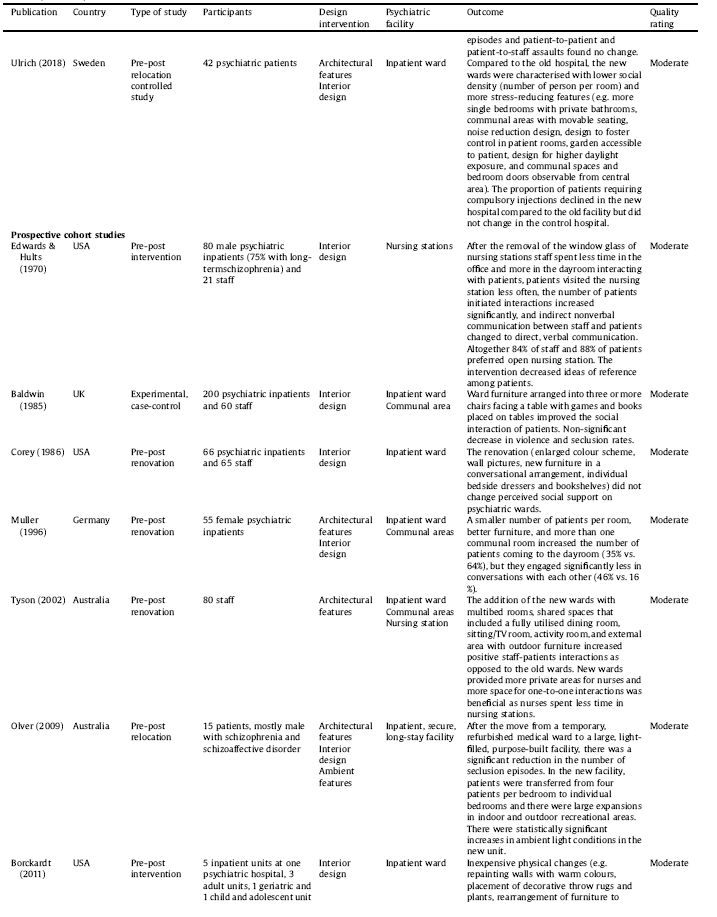

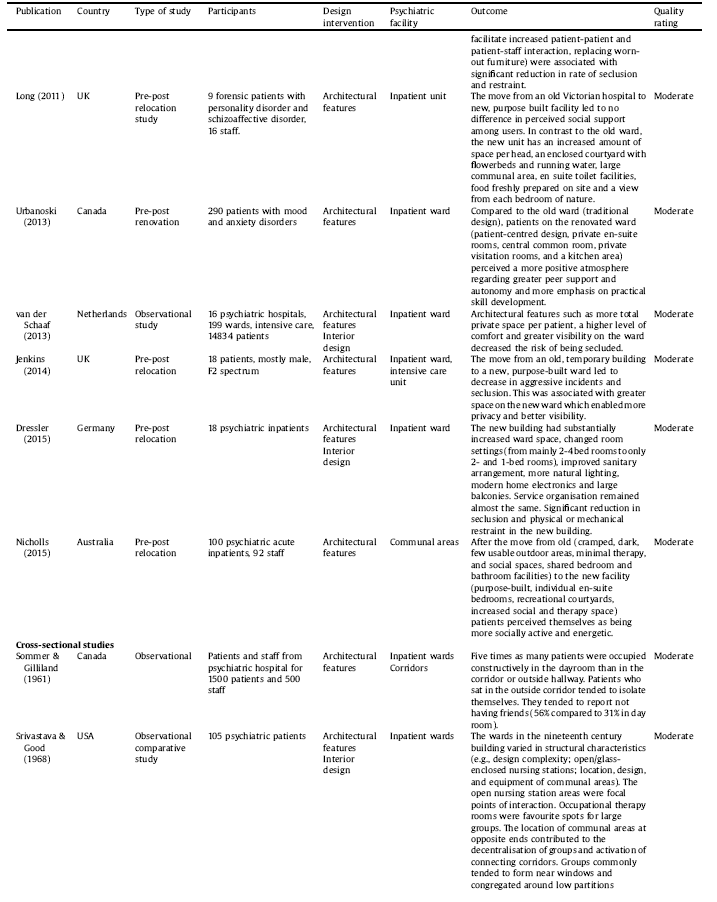

The selection procedure is displayed in Fig. 2. The final selection consists of 51 studies including 33 interventional studies in which interventions ranged from moving into a new facility (N = 15) to ward redesign (N = 10) to room(s) redesign (N = 8). Three interventional studies were randomised-controlled trials and others used pre-post evaluation. The rest of the included studies were observational in nature (N = 18), conducted in a single setting (N = 6) or across two or more settings (N = 12). Three studies were reported in two separate papers and one study was reported in three separate papers. The studies were published between 1968–2018, deriving from eight countries: United States (N = 21), United Kingdom (N = 14), Canada (N = 5), Australia (N = 4), Sweden (N = 2), Norway (N = 1), Germany (N = 2), and Netherland (N = 2). Details are listed in Table 1.

3.1. Location of psychiatric facilities

Building psychiatric facilities within local communities rather than in isolated locations has three main advantages: it encourages patients to spend more time in the community [Reference Anderson, Good and Hurtig20–Reference Skorpen, Anderssen, OEYE and Bjelland23], enables families to regularly visit patients, and reduces stigma [Reference Boydell and Everett24, Reference Curtis, Gesler, Fabian, Francis and Priebe25]. Two studies have shown that once barriers of distance are removed, most psychiatric patients used ordinary community resources for their needs [Reference Gibbons and Butler21, Reference Boydell and Everett24]. That in itself was not enough to enable patients to make new friends or renew family relationships. The architectural interventions, such as physical overlapping or integration of territories identified with various categories of users can facilitate their interactions [Reference Anderson, Good and Hurtig20]. For example, public areas can be included in the care spaces with amenities and equipment that can also be used by local residents [Reference Donald, Duff, Lee, Kroschel and Kulkarni5, Reference Anderson, Good and Hurtig20, Reference Curtis, Gesler, Priebe and Francis26].

Table 1 Study characteristics, level of design intervention, psychiatric setting and outcomes.

3.2. Architectural typology and external image

Psychiatric facilities are built in a wide range of sizes and architectural typologies [27, 28]. The purpose-built facilities are usually organized with the central section set aside primarily for offices and activity areas and the wings for patient rooms. Eight studies explored what happened when patients were relocated from nineteenth century or early twentieth century hospitals to new, smaller, homelike, purpose built facilities. Old facilities were described as overcrowded, institutional environments with multibed rooms, cramped communal areas and lack of private spaces. Six studies showed that new environments were beneficial for social interactions, and patients reported greater satisfaction with their environment and received care [Reference Chrysikou4, Reference Anderson, Good and Hurtig20, Reference Gibbons and Butler21, Reference McGonagle and Allan29–Reference Wykes31]. Two studies showed that relocation led to no difference in perceived social support (functional measure of social interaction) [Reference Nicholls, Kidd, Threader and Hungerford32, Reference Long, Langford, Clay, Craig and Hollin33]. Shepherd and colleagues compared five long-stay inpatient facilities and 20 community facilities to find out that inpatient facilities were characterised with poorer physical environment and significantly less staff-patient interactions [Reference Shepherd, Muijen, Dean and Cooney34]. A new type of psychiatric care often requires new type of environment. For example, the Soteria project provided a small (10–12 patients), homelike, intensive, interpersonally focused therapeutic milieu where patients exhibited a large effect size benefit in domains of psychopathology, work, and social functioning [Reference Bola and Mosher35].

Three studies addressed the role of corridors. Sommer and Gilliland [Reference Sommer and Gilliland36] found that patients who were friendless tended to congregate in the corridors (56% compared to 31% in day room). Another study restructured an acute 30-bed ward by breaking up long corridors and as a result, social interaction increased, interactions moved from corridors to a visiting room and a cafeteria, and there was a marked increase of visitors [Reference Whitehead, Polsky, Crookshank and Fik37]. Srivastava and Good [Reference Srivastava and Lawrence38] showed that the location of communal areas at the extreme ends of bedroom and service wings activated the connecting corridors.

3.3. Interior design interventions

Twenty-eight studies explored the role of interior design in changing social interactions. Interventions such as socio-petal furniture rearrangement (chairs arranged around tables) [Reference Holahan39, Reference Baldwin40], installation of waist-high partitions to promote private conversations [Reference Whitehead, Polsky, Crookshank and Fik37, Reference Srivastava and Lawrence38, Reference Christenfeld, Wagner, Pastva and Acrish41, Reference Holahan and Saegert42], new residential furnishings [Reference Devlin43], introduction of plants [Reference Devlin43], and availability of leisure-time resources (e.g. games, cards, books, magazines) [Reference Holahan39, Reference Baldwin40, Reference Collins, Casey, Hickey, Twemlow, Ellsworth and Hyer44, Reference Rice, Talbott and Stern45] have been found to facilitate and increase social interactions. Two studies showed that interventions such as changes in furniture style, floor covering, and colour scheme, can improve staff members’ and patients’ satisfaction with new environments but have no effect on perceived social support [Reference Corey, Wallace, Harris and Casey46] or social isolation [Reference Christenfeld, Wagner, Pastva and Acrish41].

3.4. Specific spaces within psychiatric facilities

3.4.1. Communal areas – key social spaces

Eleven studies explored the design of communal areas within psychiatric facilities. Several studies have identified lounges, dining rooms, and lobby areas as key social spaces which serve as locations for meetings with family members, having casual interactions with peers and staff, and for participating in structured therapeutic activities [Reference Wood, Curtis, Gesler, Spencer, Close and Mason30, Reference Srivastava and Lawrence38, Reference Novotna, Urbanoski and Rush47–Reference Fairbanks, McGuire, Cole, Sbordone, Silvers and Richards49]. Two studies showed that when patients are offered to use communal spaces, they usually take up this opportunity and social encounters tend to move from corridors and bedrooms into communal areas [Reference Whitehead, Polsky, Crookshank and Fik37, Reference Muller, Blumenberg and Keul50]. Howeverdue to redistribution of social activity, isolated and withdrawn behaviour can still appear in another place [Reference Fairbanks, McGuire, Cole, Sbordone, Silvers and Richards49, Reference Ittelson, Proshansky and Rivlin51]. The provision of several functionally distinct social spaces can allow opportunities for activities which replicate family life and social activity in the community [Reference Wood, Curtis, Gesler, Spencer, Close and Mason30, Reference Nicholls, Kidd, Threader and Hungerford32, Reference Olson52, Reference Urbanoski, Mulsant, Novotna, Ehtesham and Rush53].

3.4.2. Patients’ bedrooms

Individual bedrooms can give patients freedom to withdraw when feeling unwell and to determine their own rhythm of activities [Reference Curtis, Gesler, Fabian, Francis and Priebe25]. Only one study focused specifically on the bedroom size and function. Ittelson and colleagues observed social behaviour of psychiatric patients in three large hospitals in the USA with varying bedroom sizes, and found that wards with single or double rooms had more social activity, while dormitory rooms had more isolated passive behaviour (e.g. lying on a bed) [Reference Ittelson, Proshansky and Rivlin51]. Patients tend to decorate and personalise their rooms and two studies identified patients’ personal objects and photographs as important mediators of sociability [Reference Parrott54, Reference Kidd, Hasan and Trapp55]. In a small pilot study, Kidd and colleagues installed digital picture frames in patients’ rooms and this prompted patient-staff conversations, served as positive distraction for patients and improved patients’ appraisal of physical environment [Reference Kidd, Hasan and Trapp55].

3.4.3. Nursing stations

Nursing stations are focal points of staff-patients interactions, and these interactions tend to gradually decrease with a larger distance from nursing stations [Reference Srivastava and Lawrence38, Reference Polsky and Chance56]. The impact of an open vs. closed nursing station was addressed in six publications. Shattell and colleagues reported that the nurses felt caged-in by the plexiglas-enclosed nursing station [Reference Shattell, Andes and Thomas6]. After the glass had been removed, there were no statistically significant differences in patient or staff perceptions of social involvement or social support [Reference Southard, Jarrell, Shattell, McCoy, Bartlett and Judge57]. A qualitative study of the same intervention showed that nurses had mixed feelings about the intervention. Patients unanimously preferred the nurses' station without the barrier, reporting increased feelings of freedom, safety, and connection with the nurses after its removal [Reference Shattell, Andes and Thomas6]. Two studies showed that the removal of the glass panel significantly increased staff-patient interactions [Reference Chrysikou4, Reference Edwards and Hults58]. Whitehead showed that open nursing stations motivated staff to interact with patients [Reference Whitehead, Polsky, Crookshank and Fik37].

3.4.4. Smoking rooms

Three studies have indicated that the space in which patients smoke can serve as a platform for positive social interactions and resistance to institutional control [Reference Skorpen, Anderssen, OEYE and Bjelland23, Reference Curtis, Gesler, Fabian, Francis and Priebe25, Reference Wood, Curtis, Gesler, Spencer, Close and Mason30]. Skorpen and colleagues reported that patients considered the smoking room as their own arena and a place for genuine peer support, mainly because staff was not able to observe all the interactions going on in the room [Reference Skorpen, Anderssen, OEYE and Bjelland23]. Wood and colleagues explored the role of smoking areas in a newly built psychiatric hospital [Reference Wood, Curtis, Gesler, Spencer, Close and Mason59]. In the old hospital, there had been a gradual change from the days where everywhere was regarded as a smoking area to dedicated smoking rooms that over time were reduced to the size of telephone boxes in order to discourage patients from spending time there. The new hospital provided smoking shelters in the courtyards and since staff no longer needed to escort patients off the wards to smoke, this contributed to a more relaxed regime that gave patients an enhanced sense of personal freedom.

3.4.5. Outdoor spaces

Five studies explored the role of outdoor spaces and links between indoor and outdoor spaces. Srivastava and Lawrence showed that social groups on psychiatric wards commonly tended to form near windows which visually connected the ward with the outside world [Reference Srivastava and Lawrence38]. In a pre- and post-relocation study, Long and colleagues found that patients preferred wards with social areas with windows, visibility and better access to outdoor (trees and lawns) and with interior green space (courtyards with plants and water features), however, these features had no effect on perceived social support [Reference Long, Langford, Clay, Craig and Hollin33]. In another study, fresh air was mentioned to decrease the ‘suffocating’ feeling of the acute care environment [Reference Shattell, Andes and Thomas6]. Importantly, patients reported their frustration because although available, the courtyards were difficult to access and patients often felt trapped on wards [Reference Donald, Duff, Lee, Kroschel and Kulkarni5]. Carers have also emphasised their preference for domestic gardens in psychiatric facilities which they could visit with their family members [Reference Wood, Curtis, Gesler, Spencer, Close and Mason30].

3.5. Ambient features

The role of ambient features has received significantly less attention compared to architectural and interior design interventions. Smith and Jones [Reference Smith and Jones60] explored patients and staff perspection of a sensory room at a psychiatric intensive care unit. The room provided stimuli (e.g. lights, sounds, textures) and staff support for individual or group-based intervention to encourage patients to decrease stress, anger, and anxiety. The majority of patients and staff believed the room evoked a ‘sense of community’ and provided a space for socializing. In a pre-post renovation study, researchers found no significant effect of changes in lighting on social behaviour on wards [Reference Devlin43].

3.6. The relationship between physical environment, positive and negative social interactions

Eleven studies explored the relationship between physical environment and negative social interactions within psychiatric facilities. A large study of 199 psychiatric wards in the Netherlands identified 14 design features with significant effect on the risk of being secluded during admission [Reference Van Der Schaaf, Dusseldorp, Keuning, Janssen and Noothoorn61]. For example, the presence of an outdoor space, special safety measures, and patient over-crowding increased the risk of being secluded, while features such as more total private space per patient, a higher level of comfort and greater visibility on the ward decreased the risk of being secluded. The study controlled for length of stay, patient characteristics, general ward characteristics, and number of staff. The finding of an increase in risk of seclusion with the presence of an outdoor space or garden is not consistent with the literature. The authors suggested that this finding may have been biased because their data was limited to two items:the presence of an outdoor space (yes/no) and the height of the fences. Other relevant information such as the quality or attractiveness of the outdoor space or garden and whether or not patients actually had (free and/or unsupervised) access to the outdoor space, was not documented [Reference Van Der Schaaf, Dusseldorp, Keuning, Janssen and Noothoorn61]. Seven studies showed that renovation [Reference Christenfeld, Wagner, Pastva and Acrish41, Reference Southard, Jarrell, Shattell, McCoy, Bartlett and Judge57, Reference Borckardt, Madan, Grubaugh, Danielson, Pelic and Hardesty62] or relocation of patients to a new, purpose build facility [Reference Olver, Love, Daniel, Norman and Nicholls63–Reference Dressler, Rohe, Weber, Strittmatter and Fallgatter66] was associated with reduction in violent incidents, seclusion or restraint. Southard and colleagues showed that the removal of the glass from the nursing station did not lead to increase in aggression toward staff, on the contrary, seclusion and restrain rates dropped [Reference Southard, Jarrell, Shattell, McCoy, Bartlett and Judge57]. Several studies showed that interventions such as enlargement of the physical space [Reference Eggert, Kelly, Margiotta, Hegvik, Vaher and Kaya67–Reference Nijman and Rector69] or rearrangement of ward furniture [Reference Baldwin40] were not associated with significant decline in incidents. In one of these studies the new unit was substantially larger, but operated with the same number of staff which may have prevented better use of the new space [Reference Eggert, Kelly, Margiotta, Hegvik, Vaher and Kaya67, Reference Dvoskin, Radomski, Bennett, Olin, Hawkins and Dotson68].

3.7. Robustness of synthesis

The overall strength of evidence was moderate. The mean RATS score for the 22 qualitative studies was 15.1 (range 12–19), including 15 high quality studies (RATS ≥ 15) and 7 moderate quality studies (RATS = 12–14). The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) ratings for 27 quantitative studies indicated they were of moderate quality. One study was not rated because of insufficient information on methodology within this paper [Reference Kidd, Hasan and Trapp55]. One study included both qualitative and quantitative components [Reference Smith and Jones60]; both were rated as moderate quality. In two areas the quality of studies was problematic. Only ten of the included studies considered researcher bias influencing results. Secondly, 16 studies reported information on ethical issues or ethics approval. Studies published in 1970s and 1980s largely did not report this information. All papers were rated by two reviewers (NJ and JC) who achieved acceptable concordance (93%).

4. Discussion

The review identified several design features that—based on the existing evidence—may be regarded as fostering social interactions in psychiatric facilities. The main ones include community location; newly designed or renovated, small (up to 20 beds), homelike facilities with a wide range of communal areas; single/double bedrooms; open nursing stations; right balance between private and shared spaces; and specific design interventions such as arranging furniture in small, flexible groupings (see Table 2). The level of evidence linking these design features to the level of social interaction among the users of psychiatric facilities is low to moderate which is often in line with research in other medical fields [Reference Ulrich9]. However, the exception is the finding that levels of social interaction increase when introducing a range of communal spaces with comfortable, movable furniture arranged in small, flexible groupings. This evidence is notably strong because it stems from well-designed, randomised-controlled trials conducted in the 1970s [Reference Holahan39, Reference Melin and Gotestam70, Reference Peterson, Knapp, Rosen and Pither71]. In the following decades studies in this field were mainly observational with/without controls and no randomised-controlled trial had been conducted to explore the links between design solutions and social interaction (see Table 1).

Several findings from this review warrant further discussion. For example, we found that building psychiatric facilities within local communities rather than in isolated locations might improve patient interaction with others. However, it is important to emphasise that this alone is not enough to help patients to increase the size of their social networks or renew family relationships, which suggests the need for a new way of conceiving psychiatric environments. Design needs to engage people, creating opportunities for more interaction between community members and patients in or close to psychiatric facilities [Reference Donald, Duff, Lee, Kroschel and Kulkarni5, Reference Anderson, Good and Hurtig20, Reference Curtis, Gesler, Priebe and Francis26]. Similarly, homelike environments might be beneficial for social interactions between staff, patients and carers because they allow opportunities for the replication of family and community activities. One of the important themes identified in this review was the balance between private and shared spaces. In order to engage in positive interactions both staff and patients need to have their own space to retreat when feeling overwhelmed [Reference Chrysikou4, Reference Shattell, Andes and Thomas6, Reference Ittelson, Proshansky and Rivlin51, Reference Shattell, Bartlett, Beres, Southard, Bell and Judge72]. The design of these spaces can include ‘territorial’ demarcations that separate 'interaction’ from ‘private’ spaces, thus helping patients and staff to exercise choice over how and when they use the space [Reference Parr73]. Patients’ private spaces are their bedrooms, and our findings indicate that single and double bedrooms are more beneficial for social interactions than multi-bed dormitories. Studies from other medical disciplines show that single rooms are better for patient-family interactions (by providing more space and furniture than double rooms) [Reference Chaudhury, Mahmood and Valente74, Reference Eggert, Kelly, Margiotta, Hegvik, Vaher and Kaya67], while double bedrooms may have benefits for patient-patient interactions [Reference Cowart and Stoudemire75, Reference Dvoskin, Radomski, Bennett, Olin, Hawkins and Dotson68]. A systemic approach to social interaction in psychiatric facilities would treat violent incidents as types of interactions [Reference Nijman and Rector69]. The question is whether a reduction in violent incidents would increase chances for positive interactions. This remains unclear and we were not able to identify studies exploring that question. Several studies showed that renovation or relocation of patients to a new facility was associated with reduction in violent incidents, seclusion or restraint. As explained by Borckardt and colleagues, the physical changes to the environment served as constant reminders to staff of the commitment to behavioural change such as eliminating use of seclusion and restraint [Reference Borckardt, Madan, Grubaugh, Danielson, Pelic and Hardesty62]. Perhaps, the balance between private and shared spaces may be the key in understanding this relationship because violent incidents are more likely to occur on crowded wards with higher average noise level, more patient-patient interactions, and less opportunities for patients to find rest or privacy [Reference Eggert, Kelly, Margiotta, Hegvik, Vaher and Kaya67, Reference Secker, Benson, Balfe, Lipsedge, Robinson and Walker76]. There are two types of spaces that have specific connotations in psychiatric facilities: corridors and smoking rooms. While studies from other medical disciplines have identified long corridors as inefficient for staff [Reference Ulrich, Zimring, Zhu, DuBose, Seo and Choi11], in psychiatric hospitals, this feature can also be detrimental for patients by fostering social isolation [Reference Sommer and Gilliland36, Reference Whitehead, Polsky, Crookshank and Fik37]. Psychiatric patients have identified smoking rooms as important spaces that can offer ‘escape’ from observation and institutional control. With the smoking ban in place in psychiatric facilities in many countries, the question is which places will provide the same function for patients. The answer may not lie in the design of hospital environments, but rather in the type of provided care and risk management. The introduction of a comprehensive smoke-free policy seems not only be beneficial for patients’ health but also appears to reduce the incidence of physical assaults [Reference Robson, Spaducci, McNeill, Stewart, Craig and Yates77]. Despite anecdotal evidence that rooms for group psychotherapy, occupational therapy and arts therapies can facilitate social interaction, we were unable to identify studies exploring this topic.

Table 2 Key design interventions that can facilitate positive interactions among users of mental healthcare facilities.

The review has both strengths and limitations. This is the first systematic review of architectural typologies and design solutions that can potentially foster positive social interactions in psychiatric facilities and, thus, may help patients in re-establishing their social roles in the community. Using social interactions as an outcome, we focused our aim on a more robust, behavioural criterion which was helpful in clearly defining the evidence. Our synthesis was moderately robust and was limited by the fact that several studies used small convenience samples or pre- and post- assessments with no control group. The studies included both direct and indirect measurements of social interaction. The interpretation of indirect measures such as perceived social support may be problematic because the interaction between physical and social environment appears to be actively filtered by the individual’s perception and possibly mental health problems [Reference Marcheschi, Tr, Brunt, Hansson and Johansson78]. Although the review focused on adult settings (age 18–65), one study included a proportion of old age patients [Reference Devlin43] and one study included a proportion of old age and adolescent patients [Reference Borckardt, Madan, Grubaugh, Danielson, Pelic and Hardesty62]. The review focused on built environment aspects of the patient experience of a psychiatric facility and while maintaining this focus was needed to address our research question, we are aware that the overall patient experience may be influenced by a number of social and cultural influences. Studies included in this review were conducted in developed, Western healthcare systems and translating the findings into other countries and healthcare systems needs to take into consideration the role of relevant cultural and social factors. Despite these limitations, the study adds to the literature on hospital built environment by identifying several candidate interventions that could be considered when planning psychiatric facilities.

The main implication for practice is that there is considerable evidence that should be taken into account when planning or renovating psychiatric facilities. The review attempted to identify architectural typologies and design solutions which could foster helpful social interactions between users of psychiatric facilities. We hope that this will contribute to further understanding of the milieu of psychiatric facilities. Our findings can guide future design interventions, but it is important to emphasise that design or retrofitting of a psychiatric facility is a complex process. How design solutions identified in this review could potentially fit together can depend on a number of factors. For example, the environmental interventions in psychiatric facilities always need to consider safety of patients, staff, and visitors, which can be seen as both challenge and opportunity for designers and mental health professionals to come up with innovative solutions. Next, the process of design and renovation need to include patients, staff, and families to ensure that their values, beliefs and cultural backgrounds are incorporated into the planning and delivery of care. Lastly, a proactive plan can anticipate budget restrictions which may involve trade-offs or building in phases.

5. Conclusion

The design of psychiatric facilities, from needs assessments and program planning to the creation of new spaces should be guided by research evidence. This study has identified a set of interventions that should be considered in the design of psychiatric buildings to the same extent as other factors such as cost, maintenance, and harmony. Some of the identified design interventions are easy and non-costly to implement in existing hospitals (e.g. socio-petal furniture arrangement, residential-like furniture), whilst others require major investment and can be established only in new buildings (e.g. range of social spaces, good balance between social and private spaces). The findings might be particularly helpful to colleagues in countries that are moving from asylum-based to community-based services. Research in this field has been largely focused on inpatient settings. Future research should pursue well-designed studies on outpatient settings and supported housing as well as on the role of outdoor spaces.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.