1. Introduction

People with schizophrenia are characterised by an emotion recognition deficit [1,13,33,35–37]. They are less accurate at recognizing facial emotion, voice emotion [5,9,10,25] and emotion of a person from a video clip [Reference Toomey, Schuldberg, Corrigan and Green39]. The recognition of facial emotions has been studied most extensively ([30,37], review [Reference Mandal, Pandey and Prasad26]) and is influenced by illness stage with chronic patients performing worse than first-episode patients [Reference Kucharska-Pietura, David, Masiak and Phillips25]. Age and time in hospital also influence it, being old and spending a longer time in hospital are associated with worse facial emotion recognition [Reference Silver, Shlomo, Turner and Gur36]. Wolwer and colleagues [Reference Wolwer, Streit, Polzer and Gaebel42], however, did not observe worsening of facial emotion recognition over a 12-week period among patients with schizophrenia who had remitted. It is possible that the duration of illness, rather than the presence of active psychosis, plays a role. In fact, a longer duration of illness has been shown to have an adverse effect on facial emotion recognition [5,25,36] and to mediate the negative relationship between recognition of happy facial expressions and positive symptoms [Reference Silver, Shlomo, Turner and Gur36].

Earlier studies reported a negative association between emotion recognition and hallucinations and thought disorder [Reference Kohler, Bilker, Hagendoorn, Gur and Gur22], and negative symptoms [Reference Schneider, Gur, Gur and Shtasel32]. More recent studies seem to suggest that facial emotion recognition deficits are independent of the experience of positive and negative symptoms [5,6,25,37] and may instead be part of a cognitive impairment, especially in the domains of executive function and attention [21,31,37].

People with schizophrenia are known to judge social situations poorly [34,39]. They recognize facial emotions, specifically negative emotions, less accurately ([24], review [26]). Little is known about how patients with schizophrenia misattribute these emotions to other facial emotions. It is possible, but yet to be established, that they display a specific pattern of misattribution. Two studies have examined this issue so far. Peer and colleagues [Reference Peer, Rothmann, Penrod, Penn and Spaulding28] studied the association between paranoid symptoms and misattribution of happy, sad, fear and surprise emotions to the emotions of anger or disgust (misattributions to other emotions were not examined) in 91 patients with a severe mental illness (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, psychosis, bipolar disorder or other DSM disorders). They found that paranoid symptoms were related to misattribution of emotions to disgust, but not to anger. In a study of 28 stable outpatients with schizophrenia and 61 healthy controls, Kohler and colleagues [Reference Kohler, Turner, Bilker, Brensinger, Siegel and Kanes24] found that patients had difficulty in recognizing fearful and neutral expressions. They also misattributed neutral expressions to negatively toned expressions, disgust and fear, more often than healthy controls.

The present study examined facial emotion recognition deficits and the clinical and cognitive correlates of misattribution of facial emotions in a large sample of outpatients with schizophrenia. Our aims were to examine in patients with schizophrenia (a) the pattern of facial emotion recognition deficits, (b) the role of duration of illness and clinical symptoms in misattribution of emotions that are recognized less accurately by patients compared to healthy individuals, and (c) the association between facial emotion misattribution and cognitive function among the schizophrenia patients. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia would show impairment in recognizing fear and anger. We further hypothesized that in the schizophrenia group, a higher number of emotion misattributions would be associated with (a) a longer duration of illness and (b) poor executive function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and healthy controls who were recruited as part of a longitudinal study on the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on the brain. The present investigation utilized data collected at baseline (prior to CBT).

Eighty patients were recruited to the study from the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust of whom 73 provided both emotion recognition and clinical data. Thirty of these patients were allocated to receive CBT after the baseline assessment, but none had CBT at the time of or prior to baseline assessment. Inclusion criteria were the following: a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, aged between 18 and 65 years and able to speak English fluently. Patients were excluded if they had already received CBT. Clinical diagnoses were made by an experienced consultant psychiatrist (DF) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams14], who also administered the PANSS [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opier20]. Thirty healthy controls were also recruited through local advertisements.

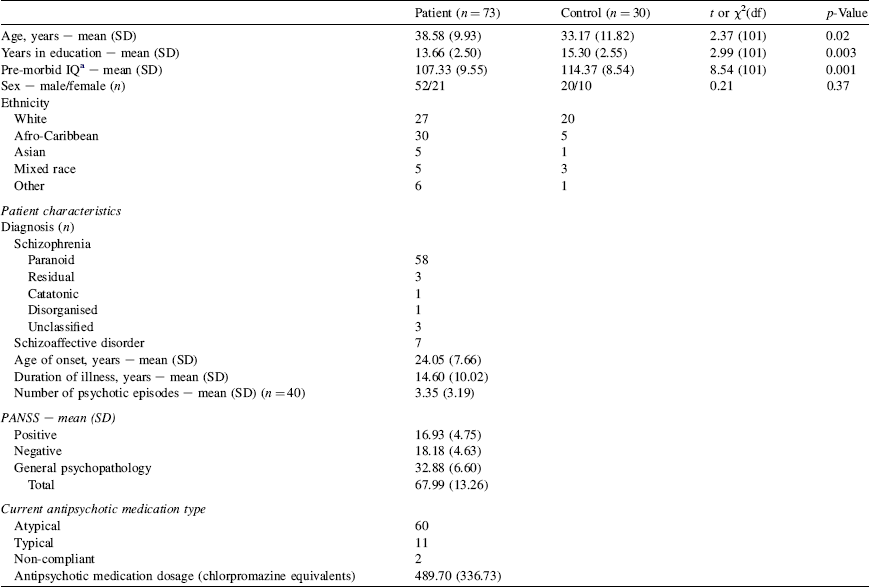

The study procedures and the use of baseline data for the purpose of the current investigation were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Joint Research Ethics Committee of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, London. All participants provided written informed consent to their participation in the longitudinal study on the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) on the brain. They were compensated for their time and travel (Table 1).

Table 1 Participant characteristics

a Pre-morbid IQ estimated by the National Adult Reading Test [Reference Nelson and Wilson27].

2.2. Measures

Participants performed the computerised Facial Emotion Attribution task designed for this study which consisted of 128 pictures of male (n = 4) or female (n = 4) faces expressing neutral, happy, angry or fearful emotions [Reference Ekman and Friesen11]. Each emotion was displayed 32 times ordered pseudo-randomly to avoid repetition of a particular emotion. Each face appeared on the screen for 3 s and then disappeared. It was followed by the question: ‘What emotion did you see?’ and a list of four emotions (neutral, happy, angry and fear) from which the participant made a choice by pressing the mouse button. The faces displayed represented the “100%” emotion of that particular facial expression. The task took approximately 8 min to complete.

All patients were also examined on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) [Reference Heaton16] that consistently reveals an executive function deficit in schizophrenia [Reference Heinrichs and Zakzanis17].

2.3. Statistical analysis

2.3.1. Group differences in facial emotion attribution

The Facial Emotion Attribution task generated four emotion attribution variables (corresponding to the correct answers for each emotion type) that were used to examine the pattern of emotion recognition deficit and 12 emotion misattribution variables (corresponding to the incorrect answers for each emotion type) that were used to study a specific pattern of misattribution. The misattribution variables were neutral-as-happy, neutral-as-anger, neutral-as-fear, happy-as-neutral, happy-as-anger, happy-as-fear, anger-as-neutral, anger-as-happy, anger-as-fear, fear-as-neutral, fear-as-happy and fear-as-anger.

A two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA; Wilk's F) was performed with the four emotion attribution variables as the within-subjects variables and group (patients and healthy controls) as the between-subjects variable. A two-way multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was then performed with the four emotion attribution variables as the within-subjects variables and group as the between-subjects variable to confirm any effects revealed by the MANOVA involving the group factor after covarying for age and years in education, since these two variables were found to differentiate the groups (see Section 3).

Emotion misattribution variables were analysed using MANOVA on the emotion attribution variables that revealed a deficit in the patient group, relative to the control group; the emotion attribution variables that showed no group difference had low error rates and therefore insufficient power to examine misattribution.

2.3.2. Duration of illness, antipsychotic dosage, clinical and cognitive correlates of facial emotion misattribution

Spearman correlations were performed between the emotion misattribution variables (that differentiated patients from controls) and duration of illness, number of psychotic episodes, antipsychotic drug level (chlorpromazine equivalents), the PANSS total and subscale scores and WCST perseverative errors.

Where both duration of illness and WCST perseverative errors were associated with an emotion misattribution variable, a multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the amount of variance explained by each of the two predictors. In this analysis, the emotion misattribution variable was the dependent variable and WCST perseverative errors and duration of illness were the predictors entered in a stepwise fashion.

All analyses were carried out using SPSS (version 15). Alpha level for significance testing was kept at p = 0.05 in all analyses. No alpha corrections were used for tests of a priori hypotheses.

3. Results

3.1. Group differences in facial emotion attribution

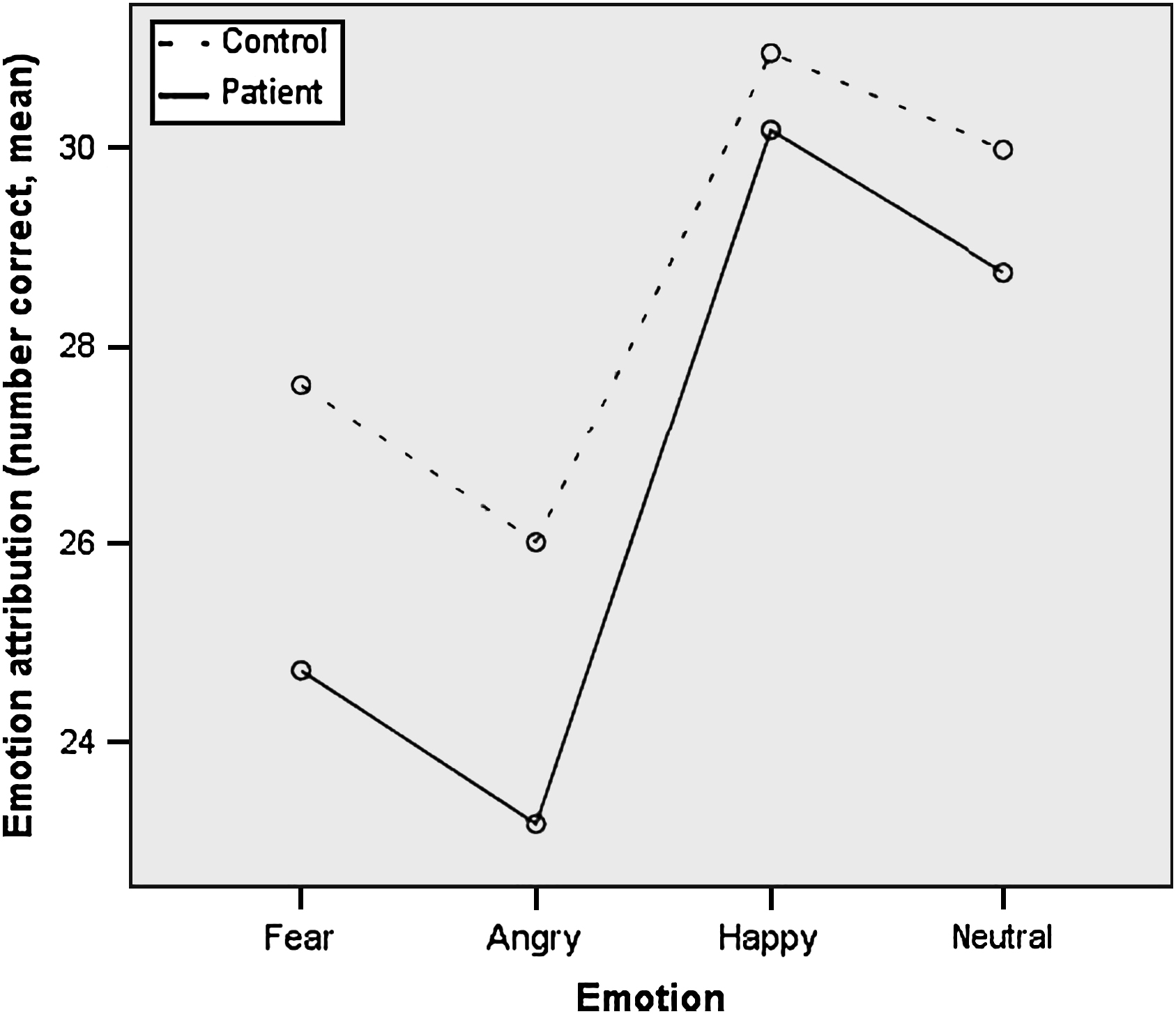

There was a significant main effect of group [F(3) = 9.30, p = 0.003] suggesting less accurate performance in the patient group. There was also a significant effect of emotion type [F(3,99) = 78.75, p < 0.001] showing that across both groups performance accuracy (maximum possible score = 32) was the highest for happy facial expressions, followed by neutral, fear and anger (see Fig. 1). More importantly, a significant group × emotion type interaction [F(3,99) = 3.19, p = 0.03] was observed revealing that patients were less accurate than controls at recognizing fear [t(101) = 2.96, p = 0.004] and anger [t(101) = 2.44, p = 0.004], but did not differ for happy and neutral facial expressions. The MANCOVA, controlling for age and years in education, did not eliminate the effect of group [F(1,99) = 6.55, p = 0.01], but reduced the significance of the group × emotion type interaction to a trend level [F(3,97) = 2.56, p = 0.06].

Fig. 1 Facial emotion attributions (number correct) in patients and controls.

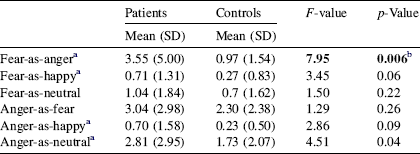

The MANOVA for group difference in misattributions (of fear and anger) was significant [F(6,99) = 2.23, p = 0.05]. Patients made significantly more fear-as-anger misattributions compared to healthy controls (see Table 2); group difference in other misattribution variables failed to survive correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 2 Number of facial emotion misattributions in patients and healthy controls

a Equal variances not assumed.

b Significant after correction (Bonferroni) for multiple comparisons.

3.2. Correlation between facial emotion misattribution and duration of illness

Misattributions of fear-as-anger were associated with a longer duration of illness (r = 0.45, p < 0.001).

3.3. Correlation between facial emotion misattribution and number of psychotic episodes, antipsychotic dosage and clinical symptoms

Misattributions of fear-as-anger and anger-as-neutral were not significantly associated with the number of psychotic episodes, antipsychotic drug level, PANSS total score or positive, negative and general psychopathology subscale scores (max r value = 0.22).

3.4. Correlation between facial emotion misattribution and cognitive function in patients

The number of misattributions of fear-as-anger correlated with WCST perseverative errors (r = 0.32, p = 0.005).

3.5. Multiple regression findings

We tested the independent contribution of duration of illness and WCST perseverative errors towards explaining the variance in fear-as-anger misattribution. Both duration of illness and WCST perseverative errors predicted fear-as-anger misattribution [F(2,71) = 12.99, p < 0.001]. Duration of illness and WCST perseverative errors predicted 16% and 10% of the misattribution variance, respectively.

4. Discussion

The key findings from this study were the following: (a) across groups, happy facial expressions were recognized most accurately, followed by neutral, then fearful and angry expressions; (b) patients were less accurate than controls in recognizing fearful and angry facial expressions; (c) patients, relative to controls, made more fear-as-anger misattributions; and (d) a longer duration of illness and perseverative errors on the WCST were independently associated with misattributions of fearful expressions as anger.

The present observation of poorer recognition of negative emotions than of positive emotions across both groups is consistent with previous literature [Reference Kucharska-Pietura, David, Masiak and Phillips25]. The patients, as expected, showed further difficulty in recognizing negative emotions relative to the healthy controls. Our finding of poorer recognition of fearful and angry facial emotions among schizophrenia patients is also consistent with evidence from a predominant facial emotion recognition deficit of threat-related expressions [10,26].

Our finding of a relationship between duration of illness and number of emotion misattributions of fear-as-anger is in line with our hypothesis. It supports previous reports of an association between a longer duration of illness and poorer accuracy of facial emotion recognition [5,25,36], but more importantly, reveals that this association is particularly relevant to fear-as-anger misattributions. Most of our patients were of the paranoid type, and it is already known that paranoid individuals tend to judge facial emotions as angry [Reference Smari, Stefansson and Thorgilsson38]. Our findings suggest that the propensity for such biases increases the longer the psychiatric disorder is experienced.

The absence of an association between PANSS symptoms and misattributions of facial emotional expressions corroborates earlier findings of no association between accuracy of facial emotion recognition and positive or negative symptoms [4,5,2,31,37]. Peer and colleagues [Reference Peer, Rothmann, Penrod, Penn and Spaulding28] suggest that an emotion misattribution bias is exacerbated by a poor ability to shift set, i.e., a perseverative response style. Our study showed that the number of WCST perseverative errors was positively associated with fear-as-anger misattributions. This finding suggests that such misattributions, at least to some extent, are cognitively mediated and that schizophrenia individuals may be adopting a rigid response style possibly perpetuated by fear among others while interacting with people with schizophrenia. Our analyses did not show an effect of age, pre-morbid IQ, number of psychotic episodes and medication on fear-as-anger or anger-as-neutral misattributions. It is, however, possible that other factors, such as duration of untreated psychosis, had some influence on our findings.

Increased affect misattributions among people with psychosis may also relate to an abnormal causal attribution style. Paranoid patients are known to make excessively external attributions for negative events relative to depressed and normal controls [Reference Kaney and Bentall19] and relative to Asperger's syndrome and normal controls [Reference Craig, Hatton, Craig and Bentall7]. Patients with persecutory and grandiose beliefs are reported to show an externalising attributional style for negative events [Reference Jolley, Garety, Bebbington, Dunn, Freeman and Kuipers18]. Such a self-preserving attributional style may function to protect self-esteem [Reference Bentall, Corcoran, Howard, Blackwood and Kinderman3].

At a neural level, increased misattributions of fear-as-anger may reflect an altered fronto-mesiotemporal circuit [Reference Williams, Das, Harris, Liddell, Brammer and Olivieri40]. A number of imaging studies on emotional recognition in schizophrenia indicate abnormality relating to processing of negative emotions [23,30]. Williams and colleagues [Reference Williams, Das, Harris, Liddell, Brammer and Olivieri40] observed greater impairment in recognition of fear in patients with paranoid schizophrenia. They reported that paranoid schizophrenia is characterised by a specific disjunction of arousal and amygdala–prefrontal circuits in relation to recognition of fearful facial expressions. This disjunction appears to be most apparent in patients with a profile of paranoia, coupled with poor social function and insight [Reference Williams, Das, Liddell, Olivieri, Peduto and David41] and is present in both the conscious and unconscious processings of fearful facial expressions [Reference Das, Kemp, Flynn, Harris, Liddell and Whitford8]. Supporting amygdala dysfunction further in paranoid schizophrenia, a recent functional MRI study involving viewing of dynamic fearful faces observed increased bilateral amygdala activation relative to healthy controls in paranoid, but not in non-paranoid, patients with schizophrenia [Reference Russell, Reynaud, Kucharska-Pietura, Ecker, Benson and Zelaya30]. The reduction in prefrontal cortical volume with a longer duration of illness [Reference Premkumar, Kumari, Corr and Sharma29] may lead to a loss of the prefrontal cortical function to regulate amygdala-autonomic function. It would be interesting to know whether such facial emotional misattributions are associated with differential activation of the prefrontal cortex and amygdala in patients with schizophrenia.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, it is difficult to separate the effect of duration of illness from that of ageing [Reference Friedman, Harvey, Coleman, Moriarty, Bowie and Parrella15], because the longitudinal effects of psychiatric illness unfold with age. Age, however, did not have a significant influence on emotion attribution/misattribution in our task in the group of healthy people (data not shown). Second, our experimental paradigm did not include sad and disgust emotions that would have informed us about the extent of misattribution of negative facial emotions. All faces were of Caucasians that may have disadvantaged participants from other ethnic groups. People are better at recognizing facial emotions among people from their own racial group [Reference Elfenbein and Ambady12], though this may not have been a factor in the particular emotion misattribution patterns seen in our study. Finally, this study used duration of illness as a measure of longitudinal illness process in a cross-sectional design which may be prone to a selection bias, since patients with a better outcome may not remain in contact with mental health services. The association we find between the longer duration of illness and emotion misattribution may therefore also include the contribution of other variables such as a higher genetic predisposition possibly leading to a type of illness with a chronic course. This possibility needs to be examined in future prospective studies. Cross-sectional studies, however, generally serve as a prelude to longitudinal prospective studies.

In conclusion, the present findings confirm that patients with schizophrenia have a bias towards misattributing negative facial emotions, especially fear-as-anger, and suggest that the propensity for such biases increases the longer the disorder is experienced. The association between misattributions of fear-as-anger expressions and WCST perseverative errors may suggest that a rigid response style in response to fearfulness is likely to be expressed by those around them.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust (067427/z/02/z; Senior Welcome Research Fellowship award to VK).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.